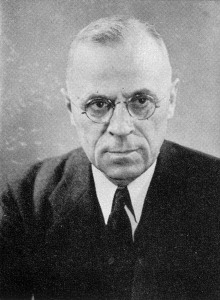

Fifty years after Lombroso’s theory of the “born criminal” an American criminologist explored the origins of criminality from a different perspective. For Edwin Sutherland people weren’t born criminal but more likely influenced by their environment. Differential association became a theory that changed the focus from biology to environment. This change signified the change of focus within criminology from biological attributes to social features.

This change, whilst it appears to have capture a wider social sciences debate at the time is also the outcome of trying to understand a world in motion. Sutherland’s theory comes in the early 20th century after the First World War and a massive economic crash. These placed in doubt the scientific and political economy of the time, putting many of these earlier ideas to the test. Popular movements challenged the authority of the state and the way hegemony suppressed people. Differential association was exploring how people learn crime by observing others; it becomes what Kornhouser called a ‘cultural deviance theory’.

What Sutherland articulated is that crime is learned through group conflict, again attempting to explain all types of crime like the biological theories before. The 20th century with its fast pace, European (World) wars, was the embodiment of modernity, progression and change. The world outside Europe began to rise against colonial rule, whilst civil rights became a rallying objective for many disenfranchised groups. In most countries worldwide women got the vote in the 20th century whilst, many countries recognised unions, and civil rights organisations, a consequence of people’s mobilisation.

It comes as no surprise then that differential association was a theory of crime that tried to account for social change and understand criminality as a process that moves within this change. The foundations of the theory in its simplest form are straightforward, covered in 9 main points:

1. Criminal behavior is learned from other individuals.

2. Criminal behavior is learned in interaction with other persons in a process of communication.

3. The principle part of the learning of criminal behavior occurs within intimate personal groups.

4. When criminal behavior is learned, the learning includes (a) techniques of committing the crime, which are sometimes very complicated, sometimes simple; (b) the specific direction of motives, drives, rationalizations, and attitudes.

5. The specific direction of motives and drives is learned from definitions of the legal codes as favorable or unfavorable.

6. A person becomes delinquent because of an excess of definitions favorable to violation of law over definitions unfavorable to violation of the law.

7. Differential associations may vary in frequency, duration, priority, and intensity.

8. The process of learning criminal behavior by association with criminal and anti-criminal patterns involves all of the mechanisms that are involved in any other learning.

9. While criminal behavior is an expression of general needs and values, it is not explained by those needs and values, since non-criminal behavior is an expression of the same needs and values.

The theory is more than a compilation of points and citing them is informative, but it doesn’t really explain the reach and extent. As a general theory of crime it can account for violent crime, theft and even white collar crimes. This reach of theory coincided with the wider discussion on “normative conflict” that focused on cultures. As discussions on cultural dominance, subcultures and the role of social groups became a sociological and criminological point these ideas introduced by Sutherland seemed to bare relevance.

There were questions already regarding the theory’s basis in terms of clarity as a cultural deviance theory, when culture focused away from poverty and social struggles. The cultural conflict seemed to resonate with certain crime categories, but it could not account for harm, leaving zemiologists to doubt the accuracy of its scope as theory. Furthermore, whilst the focus moved on from an arbitrary biology to the role of the environment some of the fundamental problems expected to be resolved in a general theory of crime remained unanswered.

So what is the answer? We can safely say that crime and most importantly criminality isn’t the product of a singularity nor its binary. How can we account for example for a social phenomenon whose definition of crime (in some instances) relies on law. A mechanism that the establishment uses to safeguard its privileges and position. The definitional factors therefore ought to transcend general conventions of biology or social interaction. Often they don’t, they merely describe the phenomenon but in closed cultural formats. There is a much more interesting and complex explanation that take us away from this binary. If you are more curious and you want to know more, why not join a criminology course and see if you can get the answer you expect or not. Criminology is a fascinating discipline not because we talk blood and bones but because we reflect on the current state of crime and imagine a world of crime (or free of crime) in the future. If you wish to share that imagination you can but join us!

https://www.northampton.ac.uk/courses/criminology-ba-hons/ https://www.northampton.ac.uk/courses/criminology-phd/ https://www.northampton.ac.uk/courses/criminology-with-psychology-ba-hons/ https://www.northampton.ac.uk/blog/why-i-chose-criminology/