Recent terrorist attacks in Manchester and the capital, like others that happened in Europe in recent years, made the public focus again on commonly posed questions about the rationale and objectives of such seemingly senseless acts. From some of the earliest texts on Criminology, terrorism has been viewed as one of the most challenging areas to address, including defining it.

There is no denial that acts, such as those seen across the world, often aimed at civilian populations, are highly irrational. It is partly because of the nature of the act that we become quite emotional. We tend question the motive and, most importantly, the people who are willing to commit such heinous acts. Some time ago, Edwin Sutherland, warned about the development of harsh laws as a countermeasure for those we see as repulsive criminals. In his time it was the sexual deviants; whilst now we have a similar feeling for those who commit acts of terror. We could try to apply his theory of differential association to explain some terrorist behaviours. however it cannot explain why these acts keep happening again and again.

At this point, it is rather significant to mention that terrorism (and whatever we currently consider acts of terror) is a fairly old phenomenon that dates back to many early organised and expansionist societies. We are not the first, and unfortunately not the last, to live in an age of terror. Reiner, a decade ago, identified terrorism as a vehicle to declare crime as “public enemy number 1 and a major threat to society” (2007: 124). In fact, the focus on individualised characteristics of the perpetrator detract from any social responsibility leading to harsher penalties and sacrifices of civil liberties almost completely unopposed. As White and Haines write, “the concern for the preservation of human rights is replaced by an emphasis on terrorism […] and the necessity to fight them by any means necessary” (1996: 139).

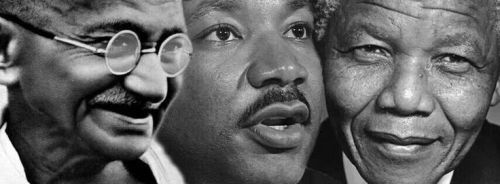

For many old criminologists who forged established concepts in the discipline, to simply and totally condemn terrorism, is not so straightforward. Consider for example Leon Radzinowicz (1906-1999) who saw the suppression of terror as the State’s attempt to maintain a state of persecution. After all, many of those who come from countries that emerged in the 19th and 20th centuries probably owe their nationhood to groups of people originally described as terrorists. This of course is the age old debate among criminologists “one man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter”. Many, of course, question the validity of such a statement at a time when the world has seen an unprecedented number of states make a firm declaration to self-determination. That is definitely a fair point to make, but at the same time we see age-old phenomena like slavery, exploitation and suppression of individual rights to remain prevalent issues now. People’s movements away from hotbeds of conflict remain a real problem and Engels’ (1820- 1895) observation about large cities becoming a place of social warfare still relevant.

Reiner R (2007), Law and Order, an honest citizen’s guide to crime and control, Cambridge, Polity Press

White R and Haines F (1996), Crime and Criminology, Oxford, Oxford University Press