Home » Articles posted by Paula Bowles (Page 9)

Author Archives: Paula Bowles

‘I read the news today, oh boy’

The English army had just won the war

The English army had just won the war

A crowd of people turned away

But I just had to look

Having read the book

(Lennon and McCartney, 1967),

The news these days, without fail, is terrible. Wherever you look you are confronted by misery, death, destruction and terror. Regular news channels and social media bombard us with increasingly horrific tales of people living and dying under tremendous pressure, both here in the UK and elsewhere in the world. Below are just a couple of examples drawn from the mainstream media over the space of a few days, each one an example of individual or collective misery. None of them are unique and they all made the headlines in the UK.

‘Deaths of UK homeless people more than double in five years’

‘Syria: 500 Douma patients had chemical attack symptoms, reports say’

‘London 2018 BLOODBATH: Capital on a knife edge as killings SOAR to 56 in three months’

So how do we make sense of these tumultuous times? Do we turn our backs and pretend it has nothing to do with us? Can we, as Criminologists, ignore such events and say they are for other people to think about, discuss and resolve?

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, Stanley Cohen, posed a similar question; ‘How will we react to the atrocities and suffering that lie ahead?’ (2001: 287). Certainly his text States Of Denial: Knowing about Atrocities and Suffering makes clear that each of us has a part to play, firstly by ‘knowing’ that these things happen; in essence, bearing witness and acknowledging the harm inherent in such atrocities. But is this enough?

Cohen, persuasively argues, that our understanding has fundamentally changed:

The political changes of the last decade have radically altered how these issues are framed. The cold-war is over, ordinary “war” does not mean what it used to mean, nor do the terms “nationalism”, “socialism”, “welfare state”, “public order”, “security”, “victim”, “peace-keeping” and “intervention” (2001: 287).

With this in mind, shouldn’t our responses as a society, also have changed, adapted to these new discourses? I would argue, that there is very little evidence to show that this has happened; whilst problems are seemingly framed in different ways, society’s response continues to be overtly punitive. Certainly, the following responses are well rehearsed;

- “move the homeless on”

- “bomb Syria into submission”

- “increase stop and search”

- “longer/harsher prison sentences”

- “it’s your own fault for not having the correct papers?”

Of course, none of the above are new “solutions”. It is well documented throughout much of history, that moving social problems (or as we should acknowledge, people) along, just ensures that the situation continues, after all everyone needs somewhere just to be. Likewise, we have the recent experiences of invading Iraq and Afghanistan to show us (if we didn’t already know from Britain’s experiences during WWII) that you cannot bomb either people or states into submission. As criminologists, we know, only too well, the horrific impact of stop and search, incarceration and banishment and exile, on individuals, families and communities, but it seems, as a society, we do not learn from these experiences.

Yet if we were to imagine, those particular social problems in our own relationships, friendship groups, neighbourhoods and communities, would our responses be the same? Wouldn’t responses be more conciliatory, more empathetic, more helpful, more hopeful and more focused on solving problems, rather than exacerbating the situation?

Next time you read one of these news stories, ask yourself, if it was me or someone important to me that this was happening to, what would I do, how would I resolve the situation, would I be quite so punitive? Until then….

Whoever fights monsters should see to it that in the process he does not become a monster. And when you look long into an abyss, the abyss also looks into you (Nietzsche, 1886/2003: 146)

References:

Cohen, Stanley, (2001), States Of Denial: Knowing about Atrocities and Suffering, (Cambridge: Polity Press)

Lennon, John and McCartney, Paul, (1967), A Day in the Life, [LP]. Recorded by The Beatles in Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, EMI Studios: Parlaphone

Nietzsche, Friedrich, (1886/2003), Beyond Good and Evil: Prelude to a Philosophy of the Future, tr. from the German by R. J. Hollingdale, (London: Penguin Books)

“A Christmas Carol” for the twenty-first century

The build up to Christmas appears more frenetic every year, but there comes a point where you call it a day. This hiatus between preparation and the festivities lends itself to contemplation; reflection on Christmases gone by and a review of the year (both good and bad). Some of this is introspective and personal, some familiar or local and some more philosophical and global.

Following from @manosdaskalou’ recent contemplation on “The True Message of Christmas”, I thought I might follow up his fine example and explore another, familiar, depiction of the festive period. While @manosdaskalou focused on wider European and global concerns, particularly the crisis faced by many thousands of refugees, my entry takes a more domestic view, one that perhaps would be recognised by Charles Dickens (1812- 1870) despite being dead for nearly 150 years.

One of the most distressing news stories this year was the horrific fire at Grenfell Tower where 71 people lost their lives. [1] Whilst Dickens, might not recognise the physicality of a tower block, the narratives which followed the disaster, would be all too familiar to him. His keen eye for social injustice and inequality is reflected in many of his books; A Christmas Carol certainly contains descriptions of gut wrenching, terrifying poverty, without which, Scrooge’s volte-face would have little impact.

In the immediacy of the Grenfell Tower disaster tragic updates about individuals and families believed missing or killed in the fire filled the news channels. Simultaneously, stories of bravery; such as the successful endeavours of Luca Branislav to rescue his neighbour and of course, the sheer professionalism and steadfast determination of the firefighters who battled extremely challenging conditions also began to emerge. Subsequently we read/watched examples of enormous resilience; for example, teenager Ines Alves who sat her GCSE’s in the immediate aftermath. In the aftermath, people clamoured to do whatever they could for survivors bringing food, clothes, toys and anything else that might help to restore some normality to individual life’s. Similarly, people came together for a variety of different celebrity and grassroots events such as Game4Grenfell, A Night of Comedy and West London Stand Tall designed to raise as much money as possible for survivors. All of these different narratives are to expected in the wake of a tragedy; the juxtaposition of tragedy, bravery and resilience help people to make sense of traumatic events.

Ultimately, what Grenfell showed us, was what we already knew, and had known for centuries. It threw a horrific spotlight on social injustice, inequality, poverty, not to mention a distinct lack of national interest In individual and collective human rights. Whilst Scrooge was “encouraged” to see the error of his ways, in the twenty-first century society appears to be increasingly resistant to such insight. While we are prepared to stand by and watch the growth in food banks, the increase in hunger, homelessness and poverty, the decline in children and adult physical and mental health with all that entails, we are far worse than Scrooge. After all, once confronted with reality, Scrooge did his best to make amends and to make things a little better. While the Grenfell Tower Inquiry might offer some insight in due course, the terms of reference are limited and previous experiences, such as Hillsborough demonstrate that such official investigations may obfuscate rather than address concerns. It would seem that rather than wait for official reports, with all their inherent problems, we, as a society we need to start thinking, and more, importantly addressing these fundamental problems and thus create a fairer, safer and more just future for everyone.

In the words of Scrooge:

“A merry Christmas to everybody! A happy New Year to all the world!” (Dickens, 1843/1915: 138)

[1] The final official figure of 71 includes a stillborn baby born just hours after his parents had escaped the fire.

Dickens, Charles, (1843/1915), A Christmas Carol, (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Co.)

“Letters from America”: III

For those of you who follow The Criminology Team on Facebook you might have caught @manosdaskalou and I live from Eastern State Penitentiary [ESP]. In this entry, I plan to reflect on that visit in a little more depth.

For those of you who follow The Criminology Team on Facebook you might have caught @manosdaskalou and I live from Eastern State Penitentiary [ESP]. In this entry, I plan to reflect on that visit in a little more depth.

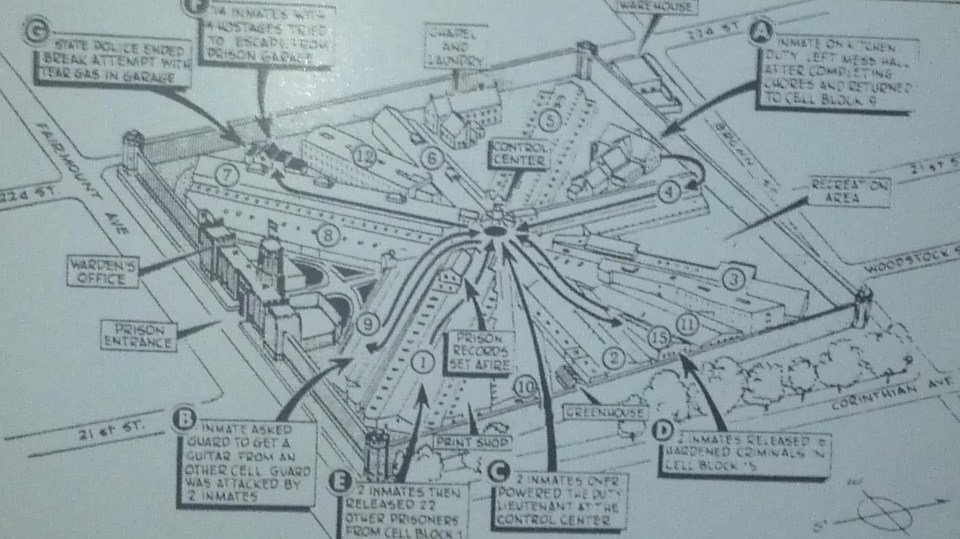

We first visited ESP in 2011 when the ASC conference was held in Washington, DC. That visit has never left me for a number of reasons, not least the lengths societies are prepared to go in order to tackle crime. ESP is very much a product of its time and demonstrates extraordinarily radical thinking about crime and punishment. For those who have studied the plans for Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon there is much which is familiar, not least the radial design (see illustration below).

This is an institution designed to resolve a particular social problem; crime and indeed deter others from engaging in similar behaviour through humane and philosophically driven measures. The Philadelphia Society for Alleviating the Miseries of Public Prisons* was philanthropic and guided by religious principles. This is reflected in the term penitentiary; a place for sinners to repent and In turn become truly penitent.

This philosophy was distinct and radical with a focus on reformation of character rather than brutal physical punishment. Of course, scholars such as Ignatieff and Foucault have drawn attention to the inhumanity of such a regime, whether deliberate or unintentional, but that should not detract from its groundbreaking history. What is important, as criminologists, is to recognise ESP’s place in the history of penology. That history is one of coercion, pleading, physical and mental brutality and still permeates all aspects of incarceration in the twenty-first century. ESP have tried extremely hard to demonstrate this continuum of punishment, acknowledging its place among many other institutions both home and abroad.

For me the question remains; can we make an individual change their behaviour through the pains of incarceration? I have argued previously in this blog in relation to Conscientious Objectors, that all the evidence suggests we cannot. ESP, as daunting as it may have been in its heyday, would also seem to offer the same answer. Until society recognises the harm and futility of incarceration it is unlikely that penal reform, let alone abolition, will gain traction.

*For those studying CRI1007 it is worth noting the role of Benjamin Rush in this organisation.

“Letters from America”: II

Having only visited Philadelphia once before (and even then it was strictly a visit to Eastern State Penitentiary with a quick “Philly sandwich” afterwards) the city is new to me. As with any new environment there is plenty to take in and absorb, made slightly more straightforward by the traditional grid layout so beloved of cities in the USA.

Particularly striking in Philadelphia are the many signs detailing the city’s history. These cover a wide range of topics; (for instance Mothers’ Day originates in the city, the creation of Walnut Street Gaol and commemoration of the great and the good) and allow visitors to get a feel for the city.

Unfortunately, these signs tell only part of the city’s story. Like many great historical cities Philadelphia shares horrific historical problems, that of poverty and homelessness. Wherever you look there are people lying in the street, suffering in a state of suspension somewhere between living and dying, in essence existing. The city is already feeling the chill winds of winter and there is far worse to come. Many of these people appear unable to even ask for help, whether because they have lost the will or because there are just too many knock backs. For an onlooker/bystander there is a profound sense of helplessness; is there anything I can do?, what should I do?, can I help or do I make things even worse?

The last time I physically observed this level of homelessness was in Liverpool but the situation appeared different. People were existing (as opposed to living) on the street but passers by acknowledged them, gave money, hot drinks, bottles of water and perhaps more importantly talked to them. Of course, we need to take care, drawing parallels and conclusions across time and place is always fraught with difficulty, particularly when relying on observation alone. But here it seems starkly different; two entirely different worlds – the destitute, homeless on the one hand and the busy Thanksgiving/Christmas shopper on the other. Worse still it seems despite their proximity ne’er the twain shall meet.

This horrible juxtaposition was brought into sharp focus last night when @manosdaskalou and I went out for an evening meal. We chose a beautiful Greek restaurant and thought we might treat ourselves for a change. We ordered a starter and a main each, forgetting momentarily, that we were in the land of super sized portions. When the food arrived there was easily enough for a family of 4 to (struggle to) eat. This provides a glaringly obvious demonstration of the dichotomy of (what can only really be described as) greed versus grinding poverty and deprivation, within the space of a few yards.

I don’t know what the answer is , but I find it hard to accept that in the twenty-first century society we appear to be giving up on trying seriously to solve these traumatic social problems. Until we can address these repetitive humanitarian crisis it is hard to view society as anything other than callous and cruel and that view is equally difficult to accept.