Home » USA (Page 2)

Category Archives: USA

At The Mouth of ‘Bloody Sunday’ #Travel #Prose #History

At the Mouth of Bloody Sunday

I know the one thing we did right, was the day we started to fight. Keep your eyes on the prize…hold on. Hold on.

Bloody Sunday in Selma only highlighted the bloody Mondays, Tuesdays, Wednesdays, Thursdays, Fridays, and Saturdays that Black people in America have faced from the first time we laid eyes on these shores. It took people to gather and protest to change. In December ’64, the good Rev. Dr. King was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for this movement. That spring in Selma, people marched across a bridge in order to highlight the normal voter suppression practices still happening throughout the south – and still in 2021.

“If you can’t vote, you ain’t free. If you ain’t free, well then you a slave.” –Intro interview to Eyes on the Prize part 6/8.

According to the National Park Service, who oversees the important civic monument now:

“On “Bloody Sunday,” March 7, 1965, some 600 civil rights marchers headed east out of Selma on U.S. Route 80. They got only as far as the Edmund Pettus Bridge six blocks away, where state and local lawmen attacked them with billy clubs and tear gas and drove them back into Selma.”

From my 7th grade social studies class circa ‘87, I would also add: The good white citizens of Selma gathered at the mouth of the bridge for the spectacle, to witness or probably participate in the oppression. We see them in the footage, films, pictures and media coverage of the events, and we know many are likely still alive. Black-n-white news footage of the days leading to Bloody Sunday show the sheriff and his angry henchmen prodding people with their clubs, plenty of ‘regular’ people watching in joy.

The people prodded? Well-dressed and behaved Black citizens of Selma and activists who’d come to support them. According to the footage, white citizens came out in droves for what they knew would be a bloody suppression of simple voting rights. As spectators, their presence made the massacre spectacular.

I’ve visited the National Voter Rights Museum and Institute at the mouth of the bridge, and there they have an actual jar of jellybeans used to test Black people coming to sign up to vote at the local government office. Yes, sitting behind that booth was a white man who demanded that a black person – any citizen of the darker complexion – accurately guess the number of jellybeans in a jar in order to be allowed – in order for him to allow them – to register to vote. I feel like I have to repeat that, or say it in different ways because it is so unbelievable.

This September, I visited a museum at the edge of the Edmund Pettus bridge in Selma, Alabama, on the way to Montgomery, the state capital. This historical museum marks local efforts to contest voter restriction practices. These practices were heinous in tone and texture, yet creative and cringe-worthy in nurture and nature. For example, consider the ingenious of these jellybean-counting white men in DC who created the separate-n-unequal space to inspire a variety of voter suppression taxes, tests and clauses throughout the south. It is these sorts of mad men who make decisions that impact the entire world as we have come to know and understand it now.

Yes, it is these sorts of men who send politicians to the state houses, and sent/send senators to Washington DC, to cajole politicians of every hue to compromise on their values. Now, we also know they send mobs to storm the capitol on the very day all the legislators gather to confirm the election results.

I know the one thing we did right, was the day we started to fight. Keep your eyes on the prize…hold on. Hold on.

Imagine yourself standing there in a museum, looking at a shelf, and there is a jar of jellybeans. There’s nothing spectacular about the jar, nor its contents. For any of us have seen something like this in virtually any kitchen, or supermarket. My granny grew, harvested and canned vegetables, so growing up I got to handle many mason jars first hand.

In fact, I love jellybeans. I used to visit the gourmet jellybeans shop in the mall after school when I was a kid. You could pick out any flavour that you liked, and I always went for blueberry, and cherry. I loved the contrast between the royal blue and Corvette red. It is a childhood fascination that my dentists still adore me for to this day. Naturally, these gourmet jellybeans were a little more expensive than the ones you get in the supermarkets, but I liked to save my money and treat myself sometimes. Plus, it felt very special being able to pick out the ones you like, and not have to discard the disgusting ones – who ever thought licorice or cola belonged on a jelly bean!?!

As a candy, jellybeans are so visually enticing. As you enter the shop, the walls are covered from floor to ceiling with all sorts of bright neon colors. Every shade of the rainbow grabs your eyes, calls to you. Between stacks of plastic bags and scoops, you are awed by the massive jars of each individual jellybean color ready for you to pick-and-mix. There are also tables with stacks of both empty and pre-filled jars. There are jars of all sizes filled with colorful patterns of jellybeans with matching ribbons tied in bows around the lids. Of course, the entire shop smells like fruit, all kinds of fruits, sweet, succulent fruits that you cannot even imagine. You are the customer, you are king. By virtue of entering the fancy shop, this is your kingdom.

Now take all of that and put it in a jar. To get to this jar, you have to enter an official government building in the town center. Next to the entrance stands an armed, uniformed white man who gives you a disgruntled look as you enter, signaling that he’s not there for your safety but aggravation. Now, as you approach, you see the jar, sitting on a counter, and behind it sits another white man. Try to imagine this white man, probably with a gun next to him or somewhere nearby, with nothing better to do than to threaten your life. Because the town is so small, he knows your last name, and may know of your family.

Since this is a small town, he knows your employer, he knows where you live as you’ve just written this down. He may even know your family, as the local history is so insidious, his family may have even owned or overseen yours at one time. Or, at that very moment, you or a family member may work for him or his kin. Your kids might play together. You may have played with him as a kid when, for example, your mother was his nanny (read-and-said-in-the-south: Mammy). Yet now, here in a free democracy, it is his job to register citizens to vote.

It is his prerogative, the birthright of this individual, plain (white) man on the other side of the glass to demand that you count the number of jellybeans in the goddamn jar. It is a privilege that no one anywhere near here has ever questioned. So, with a smile, he plops a big red “DENIED” stamp on your registration form. Of course yo’cain’t! A “killing rage” surges. Be glad you don’t have a gun with you.

My First Foreign Friend #ShortStory #BlackAsiaWithLove

I love school.

In the third grade, we had a foreign student named Graham. His parents had come over to our hometown from England with a job, and his family was to stay in our town for a year or two.

Other than Graham’s accent, at first he didn’t in anyway appear, or feel different.

The only time that Graham’s difference mattered , or that I knew Graham’s difference mattered, was on the spelling test. We had moved far away from three letter words, to larger words and sentences, and by fourth grade we were writing our own books.

But in the third grade, there was Graham on our first spelling test, and our teacher drilling words like color.

The teacher made it fun by using word association to aid in memory. Then, he paused to explain that Graham would be excused if he misspelled certain words because where he’s from, they spelt (spelled) things differently. Spell “color” differently, we all wondered?

Our teacher explained that there are many words where they add the letter U, that are pronounced in the same way. Anyway we have different accents in our own country. Heck, we had different ways of saying the word “colour” in our own city. Where does the extra-U go? Then of course, the teacher spelled out the word. He could not write it on the chalkboard because we were sitting in a circle on the area rug, on the library side of the classroom. It is then that I also realized that I had a visual memory, even visualizing words audible words, both the letters and images representing the meaning. I wanted to know why people in England spelled things differently than in America. Despite Graham’s interesting accent, and easy nature which got him along fine with everyone, he was going to have to answer some questions.

Though our teacher did not write the letters, in hearing them I could see them in my mind moving around. I started imagining how moving the different letters shifted – or did not shift – differences in sound, across distances, borders, and cultures. I started imagining how the sounds moved with the people. Irish? Scottish? People in our city claimed these origins, and they talk funny on TV. Britain has many accents, our teacher explained. “I’m English,” blurted Graham.

We didn’t know much, but we knew that except for our Jewish classmates, everyone in that room had a last name from the British Isles, which we took a few moments to discuss. Most our last names were English, like my maternal side. A few kids had heard family tales of Scottish or Irish backgrounds, German, too. One girl had relatives in Ireland. And wherever the McConnell’s are from, please come get Mitch. Hurry up!

How did we Blacks get our Anglicized names? Ask Kunta Kinte! And how did this shape Black thought/conscience, or the way we talk? I wanted to know MORE. I thought Jewish people were lucky: At least they knew who they were, and they were spoken of with respect. Since my dad is Nigerian, (and my name identifiably African) I had a slight glimpse of this. I knew I had a history, tied to people and places beyond the plantation, and outside of any textbook I’ve ever had (until now where I get to pick the texts and select the books).

My family is full of migrants, both geographically and socially, so homelife was riddled with a variety of accents. Despite migrating north, my grandparents’ generation carried their melodic Alabama accents with them their whole lives. Their kids exceeded them in education, further distancing our kin from cotton farming, both in tone and texture. This meant that my generation was the first raised by city-folk, and all the more distant from our roots since we came of age in the early days of Hip-Hop. At home, there were so many different kinds of sounds, music, talk and accents. Fascinating we can understand done another.

Our teacher also told us that Americans also used some of the same words differently. Now, I’ve lived here in the UK for a decade and I can’t be bothered to call my own car’s trunk a boot. Toilet or loo? Everybody here gets it. Unfortunately, Graham explained that he knew the British term for what we call ‘eraser’, which the teacher couldn’t gloss over because we each had one stashed in our desks, and he knew we’d have the giggles each time the word was mentioned.

I was still struck by the fact that in spite of all these differences and changes, meanings of words could shift or be retained, both in written and spoken forms. I wanted to know more about these words – which words had an extra U – and where had the British got their languages and accents. For me, Graham represented the right to know and experience different people, that this was what was meant by different cultures coming together.

“Here I am just drownin’ in the rain/With a ticket for a runaway train…” – Soul Asylum, 1992, senior year.

In retrospect it’s weird that Graham’s my first foreign friend. Both my father and godmother immigrated to America – initially to attend my hometown university. They’d come from Nigeria and China, respectively, and I’d always assumed that I’d eventually visit both places, which I have. Perhaps this particular friendship sticks with me because Graham’s the first foreign kid I got to know.

Through knowing Graham, I could for the first time imagine myself, in my own shoes, living in another part of the world, not as a young adult like my folks, but in my 8-year-old body. What interested me more was that I could also see Graham was not invested in the macho culture into which we were slowly being indoctrinated (bludgeoned). For example, Graham had no interest in basketball, which is big as sh*t in Kentucky. Nor did I. “Soccer is more popular over there,” our teacher explained, deflecting from Graham’s oddness. “But they call it football.” Who cares! I’d also seen Graham sit with his legs crossed, which was fully emasculating as far as I knew back then. The teacher defended him, saying that this also was different where Graham came from. I definitely knew I wanted to go there, and sit anyway I wanted to sit.

Kisses from Granny Don’t Count! #BlackenAsiaWithLove #ShortStory

In America, and most certainly in the land of Dixie and cotillions, at the end of junior high school year we have a tradition of getting our senior class rings. By “getting,” I mean individually buying a ring from the same one or two companies in our city who cash in on this ritual annually. We knew that many of us had to foot the bill with our own after-school jobs, while others’ parents could virtually write a blank check! (Hopefully, at least, or perhaps most assuredly, somebody in the school system gets a kickback from all this cash flow.)

While class rings appeared personalized, the rings – and the ritual – were effectively mass manufactured, complete with standardized shapes and design features: school’s name and mascot – in our case a bear – class year (1993!), and maybe our initials inscribed inside. Oh, and a heteronormative adolescent sexualized ritual to which I shall return shortly.

Rings are generally presented at a school ceremony. Until graduation, class rings are worn facing the wearer as motivation towards the ultimate achievement, after which it is worn outward as a badge of pride and honor. A graduating class could all agree to the same design – usually the school colors – which I believe the majority of my class did. While I prefer the look of silver against my dark skin, our school colors were royal blue and gold, so classes at our school often got blue sapphire set in the lowest Karat gold available that didn’t look cheap. For such a notoriously liberal school (i.e., gender and racially/geographically* integrated by design), this was one of the few explicit acts of conformity.

‘You Wear it Well’ – DeBarge, 1985

The next part of the tradition is having 100 different people turn the ring, as sort of an acknowledgement of becoming a senior. The first 99 turn it in one direction, while the final person reverses the order. This clockwise/counter-clockwise turn seals the deal. Yet get this, you’re supposed to kiss the hundredth person who turns the ring. You say the word “kiss” in front of most any group of adolescents and they’ll giggle. We knew what kind of kiss was meant. FRENCH like fries! Somehow becoming a senior in high school had been coopted by this hetero-ritual, a hetero-rite of passage (het-or-no-rites!).

I am troubled that this academic milestone is linked to gender. Worse, the ritual is predictably a performance act that fixes gender to normative sexual roles; yes, heteropatriarchy. Worse still, this binary gender performance is discrete, couched in achieving a basic education.

The ring dealer comes to school and makes a sales pitch to the class, and sets up a booth in the lobby after school. In his pitch, he promises a ‘free’ glossy little form to collect all the signatures. It was a bait and switch. These dealers sold us the rings but gave us the forms, the evidence we needed to prove we’d passed another stage towards adulthood. And what were we supposed to do with the blank glossy forms? Come back to school and boast?

The first 50 or so signatures were just us. Our own schoolmates turning each other’s rings, filling in each other’s forms on the very day the rings arrived. Family filled in a lot, too. I distinctly remember a teacher or two requesting to be excluded from the tradition, or take part in the ring ritual of becoming a senior, else we whittle their fingers away.

We all know everybody only wanted to see who signed the final line – a prompt to incite heteronormalizing speech-acts. Well, a few folks weren’t single and already had that 100th spot reserved and filled by sundown. Needless to say, kisses from granny don’t count! I’m pretty sure this wasn’t written on the dealer’s well-crafted sheet. Our market dominated, heteronormative introduction to adulthood for all to see.

I’d attended the same school since second grade so I’d seen people celebrate this class ring ritual for years, and even attended several graduations. I’d watched the “Senior run” year after year – a day at the end of school, when the graduating class runs through all the halls, cheering, banging on lockers as all the kids in all the classes rush out to line the hallways and egg them on. I loved school, adored our school, adored my classmates, and even looked forward to our turn, though parting so bittersweet.

At 16, I was only starting to be able to fully disidentify with the barrage of heterosexualized norms that engulfed me. I had to disentangle heterosexuality from virtually every facet of life – even finishing high school, a normal step we’re all expected to take. It’s as if to gain access to what bell hooks calls ‘the good life’ one had to signify alignment with compulsory heterosexuality.

I knew that I could not even turn my ring 100 times without kissing a girl. No way I’d risk putting a guy’s name at the end of that glossy list – someone I’d actually dreamt of French-kissing. Not like I knew any guy who’d be game. Damn. This was a lot of pressure. This junior prom was forcing me to make all kinds of adult decisions.

“The more I get of you, the stranger it feels…”

I was 16, and wasn’t out yet. Unlike at twelve when these feelings first bubbled over, by 16 I was on the cusp of self-acceptance, and preparing to face this possibility that I was gay. Perhaps it was pure timing. By the 11thgrade I knew for sure I’d be leaving home months after graduation, which was suddenly within reach. I could chart my own homo path. But still, at that age, I had doubts. I tried seriously dating a young woman as my last-ditch effort to see if I was straight or (at least) bisexual.

Kaye wasn’t a classmate, which wouldn’t have worked anyway because in retrospect all my classmates already knew, and had decided to accept me without question. Kaye attended an all-girls’ school, so we’d met through an extracurricular, Black youth empowerment program. Kaye was clearly college bound. She had her own dreams and ambitions, and pursued them – an ideal mate for me. She was the most attractive woman I knew, both inside and out, both to me and others. Yes, THAT sister who is not invulnerable, but has it all together. If she didn’t do, then dammit I was gay!

Fortunately, my girl was smart. And by smart, I mean that she was intelligent, real smart as in NOT clueless at all. We agreed to a kiss on the cheek, and she’d sign the last line on my glossy form. And by ‘agreed to’, I mean that this is what Kaye put on the table as her firm and final offer. She also had the good sense to let me turn her ring, too, but she reserved the 100th signature for someone special. I respected that. This clarified our plutonic status – no Facebook updates needed: I’m gay.

“Gotta find out what I meant to you…You were sweet as cheery pie/ Wild as Friday night”

Black History Month: A Final Thought

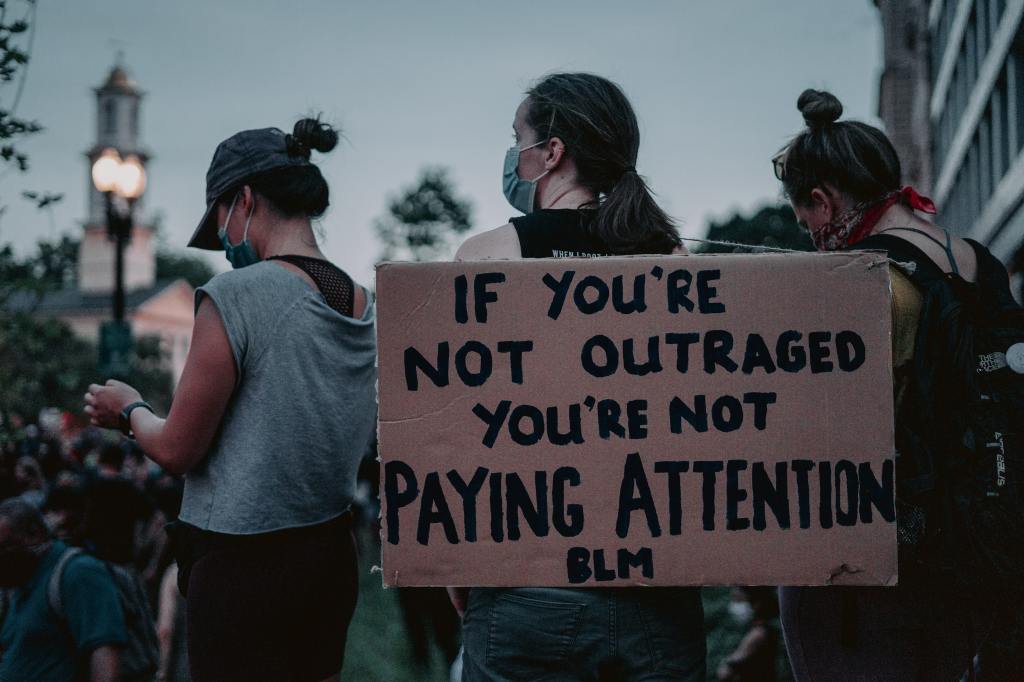

As we come to the end of Black History Month it is important to shine a light on the Black Lives Matters Movement and highlight the historical significance to the problematic discourse of racialisation.

Black history month is an opportunity for people from the various pockets of the Black community to learn about our own history and educate those who are not from the Black community, in order to decolonise our institutions and our society. As Black people we have our own history formed by systemic oppressions and great triumphs. While it is easy (and lazy) for institutions to use terms such as BAME and People of Colour (POC) these problematic uses of language oppress blackness. We are not a monolith of coloured people. Different racialised groups have and will experience, and uphold difference, harms and achievements within society. Furthermore, it would be naïve to ignore the narrative of anti-blackness that people from racialised groups uphold. Therefore, it is important for us and people that look like us, to continue to have the space to talk about our history and our experiences.

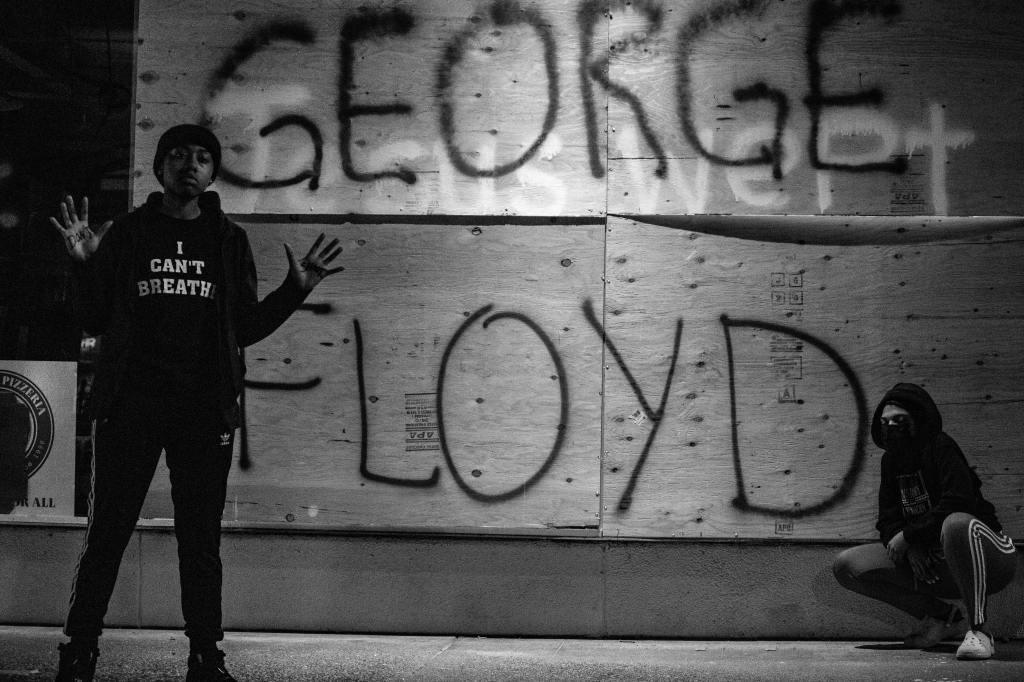

For many people in the UK and indeed around the world BLM became a mainstream topic for discussion and debate following the murder of George Floyd. While the term BLACK LIVES MATTER is provocative and creates a need for debate, it signifies the historical ideology that black lives haven’t mattered in historical and in many ways, contemporary terms.

While it is easy to fall into the trap of describing the Black experience as an experience of victimhood, Black history months allows us to look deep at all our history and understand why and where we are as a society.

The UK is one of the most diverse places in the world, yet we continue to fall prey to the Eurocentric ideology of history. And while it is important to always remember our history, the negativity of only understanding black history from the perspective of enslavement needs to be questioned. Furthermore, the history of enslavement is not just about the history of Black people, we need to acknowledge that this was the history of the most affluent within our society. Of course, to glaze over the triangle trade is problematic as it allows us to understand how and why our institutions are problematic, but it is redundant to only look at Black history from a place of oppression. There are many great Black historical figures that have contributed to the rich history of Britain, we should be introducing our youth to John Edmonstone, Stuart Hall, Mary Prince and Olive Morris (to name a few). We should also be celebrating prominent Black figures that still grace this earth to encourage the youth of today to embrace positive Black role models.

Black history for us, is not just about the 1st-31st of October. We are all here because of history we need to start integrating all our history into our institutions, to empower, educate and to essentially make sense of our society.

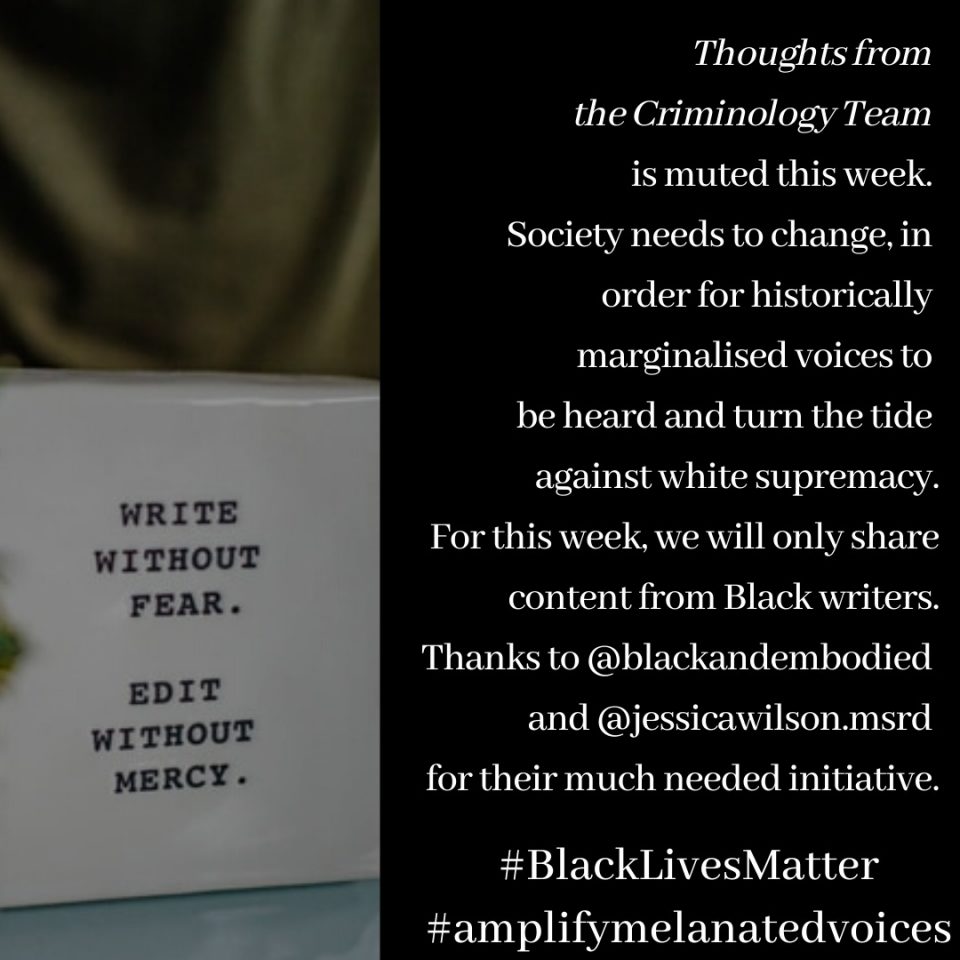

#amplifymelanatedvoices 2021

In June 2020, the Thoughts from the Criminology Team blog took part in an initiative started by @blackandembodied and @jessicawilson.msrd over on Instagram. For one week, we only posted/reshared blog entries from Black writers to reiterate our commitment to do better in the fight against White supremacy, racist ideology, as well as individual, institutional, and structural violences.

With the first-year anniversary of George Floyd’s murder fast approaching (25 May), we want to run the same initiative, with entries which focus on aspects of this heinous crime. We recognise that whilst the world was shocked by George Floyd’s racist murder, for many of our friends, families and communities, his death represented generational trauma. For this reason, we have not requested new entries (although they are always welcome) and instead want our readers to have another opportunity to (re-)engage with some excellent and thoughtful entries from our talented writers.

Take some time to read, think and reflect on everything we have learned from George Floyd’s murder. In our discipline, we often strive for objectivity and run the risk of losing sight of our own humanity. So, do not forget to also look after yourself and those around you, whether physically or virtually. And most importantly listen to each other.

The 7 shots of Isaiah Brown (April, post-George Floyd murder case) #BlackenAsiaWithLove

Isaiah Brown was shot by the policeman who’d given him a ride home less than an hour earlier, after his car had broken down at a gas station. He was shot 3 minutes into his 9-1-1 call. The cop mistook the cordless phone Isaiah was holding for a gun. This was the very phone he’d mentioned to the 9-11 dispatcher, using the very same cordless phone from his home. On the 9-1-1 call, Isaiah is explicitly asked, and confirms that he is unarmed, also that he was walking down the street on the phone, escaping a volatile situation.

On the call, it’s clear that Isaiah was reaching out for a lifeline – calling out from hell in sheer crisis. It wasn’t that he was in danger, he had the emotional maturity to call for help when he felt himself at risk of endangering another. “I’m about to kill my brother,” he calmly tells the dispatcher, who by now can start to hear him panting from walking.

“Do you understand that you just threatened to kill your brother on a recorded line on 9-1-1,” she asks calmly. “Mmm Hmm,” he confirms casually. He was calling her for help, and by now it’s clear that she’s attempting to keep him talking, i.e. redirect his attention from his crisis by having him describe the crisis. She’s helping Isaiah to look at his situation objectively, and it’s working. This is a classic de-escalation tool that anyone who has ever taken care of a toddler knows. Isaiah calmly and rationally confirmed that he knew the implications of his words, and he kept pleading for help.

This was a call about a domestic dispute and there was talk of a gun, which never materialized, neither did the caller nor his brother in the background suggest the actual presence of a gun. Isaiah can be heard twice ushering someone out with him, and by his tone it seemed that he was speaking to a child, using a Black girl’s name. None of Isaiah’s ushering is noted in the transcript. In hearing so many keystrokes, one wonders which parts of this is being taken down. Again, she asked him to confirm that he was unarmed. In fact, she seemed bewildered that he was using a house phone, yet still able to walk down the street, again, evidently attempting to de-escalate the situation. How many times have you told some to “take a walk!”

“How are you walking down the road with the house phone,” she asks. “because I can,” he says, and leaves it at that.

In the background of the call, we hear police sirens approaching. “You need to hold your hands up,” she says. “Huh,” he asks. “Hold your hands up,” she says sharply, as if anticipating the coming agitation. It’s interesting to note here that we, too, know that despite the casual nature of this distress call, despite all clear and explicit confirmation that the gentleman was unarmed, and regardless of the fact that the dispatcher knew that Isaiah would be in the street when officers approached, the raising in alarm in her voice betrayed the fact that she knew the officer would escalate the situation.

“Why would you want to do something like that,” she calmly asks, he calmly answers. She engages him in this topic for a while, and we can hear the background become quieter. His explanations are patchy and make little sense, yet he remains calm. By now, it’s clear that the caller is of danger to no one else but his brother, and that he’d managed to create some physical distance between the two. So far, nothing suggests anyone is about to die. Yet, the officer arrives, and within 30 seconds, 7 shots are fired, Isaiah is down.

After the 7 shots are fired, you can hear someone moaning in pain, and you can’t exactly tell if it’s Isaiah or the dispatcher; the dispatcher’s recording continues. After the shots are fired, and it’s clear from the audio that the victim is moaning in pain, the cop continues to bark out orders: “Drop the gun” and so forth. He’s just 7 times, we hear a fallen man, and the cop is still barking in anger and anguish. Is he saying “drop the gun” to Isaiah, or performing for the record, as Black twitter has suggested? Confusingly, moments later the officer is heard playing Florence Nightingale, complete with gentle bedside manner. We hope Isaiah survives; issuing aid at this moment is life-saving.

“He just shot ‘em, the dispatcher says to someone off call, who can now be heard on another dispatch call regarding the incident. “I got you man” the policeman says to Isaiah moments after shooting him, then mercifully: “I’m here for you, ok.”

Now, in the distance, we hear the familiar voice of Isaiah’s brother calling out, “Hey, what’s going on, bro?” “It’s ok” the officer calls out quickly. He never says what’s just happened. Then, “Go to my car, grab the medical kit,” he calls out to the brother. “You shot ‘em,” the brother asks. The cop says nothing.

The previous news report on the network nightly news was about Merrick Garland launching a civil rights investigation into my hometown’s police force, just over a year after the police murdered Breonna Taylor on my mother’s birthday. “It’s necessary because, police reform quite honestly, is needed, in nearly every agency across the country” says Louisville Metro Police Chief, Erika Shields. On that area’s local news website reporting this story, the next news story bleeds reads: “ Black gun ownership on the rise,” on no one should wonder why. But, this is America, so the headline finishes with: “But Black gun store owners are rare.” The all-American solution – more peace-makers!

Please stop ignoring our distress, or minimizing our pain with your calls to “go slow.” How slow did Isaiah have to move to avoid getting shot 7 times by a cop who’d just shown him an act of kindness and mercy!?! #BLM #BlackLivesMatter #Seriously #Nokidding

The Chauvin verdict may not be the victory we think it is

At times like this I often hate to be the person to take what little hope people may have had away from them, however, I do not believe the Chauvin verdict is the victory many people think it is. I say people, but I really mean White people, who since the Murder of George Floyd are quite new to this. Seeing the outcry on social media from many of my White colleagues that want to be useful and be supportive, sometimes the best thing to do in times like these is to give us time to process. Black communities across the world are still collectively mourning. Now is the time, I would tell these institutions and people to give Black educators, employees and practitioners their time, in our collective grief and mourning. After the Murder of George Floyd last year, many of us Black educators and practitioners took that oppurtunity to start conversations about (anti)racism and even Whiteness. However, for those of us that do not want to be involved because of the trauma, Black people recieving messages from their White friends on this, even well-meaning messages, dredges up that trauma. That though Derek Chauvin recieved a guilty verdict, this is not about individuals and he is still to recieve his sentence, albeit being the first White police officer in the city of Minneapolis to be convicted of killing a Black person.

Under the rallying cry “I can’t breathe” following the 2020 Murder of George Floyd, many of us went to march in unison with our American colleagues. Northamptonshire Rights and Equality Council [NREC] organised a successful protest last summer where nearly a thousand people turned up. And similar demonstrations took place across the world, going on to be the largest anti-racist demonstration in history. However, nearly a year later, institutional commitments to anti-racism have withered in the wind, showing us how performative institutions are when it comes to pledges to social justice issues, very much so in the context race. I worry that the outcome of the Chauvin verdict might become a “contradiction-closing case”, reiterating a Facebook post by my NREC colleague Paul Crofts.

For me, a sentence that results in anything less than life behind bars is a failure of the United States’ criminal justice system. This might be the biggest American trial since OJ and “while landmark cases may appear to advance the cause of justice, opponents re-double their efforts and overall little or nothing changes; except … that the landmark case becomes a rhetorical weapon to be used against further claims in the future” (Gillborn, 2008). Here, critical race theorist David Gillborn is discussing “the idea of the contradiction-closing case” originally iterated by American critical race theorist Derrick Bell. When we see success enacted in landmark cases or even movements, it allows the state to show an image of a system that is fair and just, one that allows ‘business as usual’ to continue. Less than thirty minutes before the verdict, a sixteen-year-old Black girl called Makiyah Bryant was shot dead by police in Columbus, Ohio. She primarily called the police for help as she was reportedly being abused. In her murder, it pushes me to constantly revisit the violence against Black women and girls at the hands of police, as Kimberlé Crenshaw states:

“They have been killed in their living rooms, in their bedrooms, in their cars, they’ve been killed on the street, they’ve been killed in front of their parents and they’ve been killed in front of their children. They have been shot to death. They have been stomped to death. They have been suffocated to death. They have been manhandled to death. They have been tasered to death. They have been killed when they have called for help. They have been killed while they have been alone and they have been killed while they have been with others. They have been killed shopping while Black, driving while Black, having a mental disability while Black, having a domestic disturbance while Black. They have even been killed whilst being homeless while Black. They have been killed talking on the cellphone, laughing with friends, and making a U-Turn in front of the White House with an infant in the back seat of the car.”

Professor Kimberlé Crenshaw (TED, 2018)

Whilst Chauvin was found guilty, a vulnerable Black girl was murdered by the very people she called for help in a nearby state. Richard Delgado (1998) argues “contradiction-closing cases … allow business as usual to go on even more smoothly than before, because now we can point to the exceptional case and say, ‘See, our system is really fair and just. See what we just did for minorities or the poor’.” The Civil Rights Movement in its quest for Black liberation sits juxtaposed to what followed with the War on Drugs from the 1970s onwards. And whilst the Stephen Lawrence Inquiry was seemingly one of the high points of British race relations followed with the 2001 Race Relations Act, it is a constant fallback position in a Britain where racial inequalities have exasperated since. That despite Macpherson’s landmark report, nothing really has changed in British policing, where up until recently London Metropolitan Police Service had a chief that said it wasn’t helpful to label police as institutionally racist.

Scrolling the interweb after the ruling, it was telling to see the difference of opinion between my White friends and colleagues in comparison to my Black friends and colleagues. White people wrote and tweeted with more optimism, claiming to hope that this may be the beginning of something upward and forward-thinking. Black people on the other hand were more critical and did not believe for a second that this guilty verdict meant justice. Simply, this ruling meant accountability. Since the Murder of George Floyd, there have been numbers of conversations and discourses opened up on racism, but less so on White supremacy as a sociopolitical system (Mills, 2004). My White colleagues still thinking about individuals rather than systems/institutions simply shows where many of us still are, where this trial became about a “bad apple”, without any forethought to look at the system that continues enable others like him.

Even if Derek Chauvin gets life, I am struggling to be positive since it took the biggest anti-racist demonstration in the history of the human story to get a dead Black man the opportunity at police accountability. Call me cynical but forgive me for my inability to see the light in this story, where Derek Chauvin is the sacrificial lamb for White supremacy to continue unabted. Just as many claimed America was post-racial in 2008 with the inaugaration of Barack Obama into the highest office in the United States, the looming incarceration (I hope) of Derek Chauvin does not mean policing suddenly has become equal. Seeing the strew of posts on Facebook from White colleagues and friends on the trial, continues to show how White people are still centering their own emotions and really is indicative of the institutional Whitenesses in our institutions (White Spaces), where the centreing of White emotions in workspaces is still violence.

Derek Chauvin is one person amongst many that used their power to mercilessly execute a Black a person. In our critiques of institutional racism, we must go further and build our knowledge on institutional Whiteness, looking at White supremacy in all our structures as a sociopolitical system – from policing and prisons, to education and the third sector. If Derek Chauvin is “one bad apple”, why are we not looking at the poisoned tree that bore him?

Referencing

Delgado, Richard. (1998). Rodrigo’s Committee assignment: A sceptical look at judicial independence. Southern California Law Review, 72, 425-454.

Gillborn, David. (2008). Racism and education: Coincidence or conspiracy? London: Routledge.

Mills, Charles (2004) Racial Exploitation and the Wages of Whiteness. In: Yancy, George (ed). What White Looks Like: African American Philosophers on the Whiteness Question. London: Routledge.

TED (2018). The urgency of intersectionality | Kimberlé Crenshaw. YouTube [online]. Available.

White Spaces. Institutional Witnesses. White Spaces. Available.

Chauvin’s Guilty Charges #BlackAsiaWithLove

Charge 1: Killing unintentionally while committing a felony.

Charge 2: Perpetrating an imminently dangerous act with no regard for human life.

Charge 3: Negligent and culpable of creating an unreasonable risk.

Guilty on all three charges.

Today, there’s some hope to speak of. If we go by the book, all the prosecution’s witnesses were correct. Former police officer Chauvin’s actions killed George Floyd. By extension, the other two officers/overseers are guilty, too, of negligence and gross disregard for life. They taunted and threatened onlookers when they weren’t helping Chauvin kneel on Floyd. Kneeling on a person’s neck and shoulders until they die is nowhere written in any police training manual. The jury agreed, and swiftly took Chauvin into custody . Yet, contrary to the testimonials of the police trainers who testified against Chauvin’s actions, this is exactly what policing has been and continues to be for Black people in America.

They approached Floyd as guilty and acted as if they were there to deliver justice. No officer rendered aid. Although several prosecution witnesses detailed how they are all trained in such due diligence, yet witnesses and videos confirm not a bit of aid was rendered. In fact, the overseers hindered a few passing-by off-duty professionals from intervening to save Floyd’s life, despite their persistent pleas. They acted as arbiters of death, like a cult. The officers all acted in character.

Teenager Darnella Frazier wept on the witness stand as she explained how she was drowning in guilt sinceshe’d recorded the video of Chauvin murdering Mr. Floyd. She couldn’t sleep because she deeply regrated not having done more to save him, and further worried for the lives many of her relatives – Black men like George Floyd, whom she felt were just as vulnerable. When recording the video, Ms. Frazier had her nine-year-old niece with her. “The ambulance had to push him off of him,” the child recounts on the witness stand. No one can un-see this incident.

History shows that her video is the most vital piece of evidence. We know there would not have even been a trial given the official blue line (lie). There would not have been such global outcry if Corona hadn’t given the world the time to watch. Plus, the pandemic itself is a dramatic reminder that “what was over there, is over here.” Indeed, we are all interconnected.

Nine minutes and twenty seconds of praying for time.

Since her video went viral last May, we’d seen footage of 8 minutes and 46 seconds of Chauvin shoving himself on top of ‘the suspect’. Now: During the trial, we got to see additional footage from police body-cameras and nearby surveillance, showing Chauvin on top of Mr. Floyd for nine minutes and twenty seconds. Through this, Dr. Martin Tobin, a pulmonary critical care physician, was able to walk the jury through each exact moment that Floyd uttered his last words, took his last breath, and pumped his last heartbeat. Using freeze-frames from Chauvin’s own body cam, Dr. Tobin showed when Mr. Floyd was “literally trying to breathe with his fingers and knuckles.” This was Mr. Floyd’s only way to try to free his remaining, functioning lung, he explained.

Nine minutes and twenty seconds. Could you breathe with three big, angry grown men kneeling on top of you, wrangling to restrain you, shouting and demeaning you, pressing all of their weight down against you?

Even after Mr. Floyd begged for his momma, even after the man was unresponsive, and even still minutes after Floyd had lost a pulse, officer Chauvin knelt on his neck and shoulders. Chauvin knelt on the man’s neck even after paramedics had arrived and requested he make way. They had to pull the officer off of Floyd’s neck. The police initially called Mr. Floyd’s death “a medical incident during police interaction.” Yes, dear George, “it’s hard to love, there’s so much to hate.” Today, at least, there’s some hope to speak of.

The First Day of Freedom -#SpOkenWoRd #BlackenAsiaWithLove

What must September 30th have felt like?

On a season seven episode of historian Prof. Skip Gates’ public broadcast show, Finding Your Roots, Queen Latifah read aloud the document that freed her first recorded ancestor:

“Being conscious of the injustice and impropriety of holding my fellow creature in state of slavery, I do hereby emancipate and set free one Negro woman named Jug, who is about 28 years old, to be immediate free after this day, October 1st, 1792. -Mary Old” (slave-owner).

“No way,” Latifah sighs, and repeats this twice after she recites the words “set free.”

“OMG, I’m tingling right now,” she whispers.

‘The Queen L-A-T-I-F-A-H in command’ spent her entire rap career rapping about freedom.

And: U-N-I-T-Y!

Now she asks: “What must that have been like…to know that you are free?”

Indeed, what did it feel like to hold your own emancipation piece of paper for the first time?

Or, to receive this piece of paper in your (embondaged) hands?

Or, pen a document liberating another who you believe to be a fellow human being?

What must September 30th have felt like for this slave…

The day before one’s own manumission, the eve of one’s freedom?

What ever did Ms. Jug do?

How can I…

How can I claim any linkages to, or even feign knowing anything about –

Let alone understand – anyone who’s lived in bondage?

However, I can see that

We’re all disconnected from each other today, without seeking to know all our own pasts.

Or, consider:

The 1870 Federal census was the first time Africans in America were identified by name, Meaning:

Most of us can never know our direct lineage …no paper trail back to Africa.

So, what must it feel like to find the first record of your ancestors – from the first census –

Only to discover a record of your earliest ancestor’s birthplace: Africa!?!

Though rare, it’s written before you that they’d survived capture and permanent separation,

The drudgery of trans-Atlantic transport, and

A life-till-death of cruel and brutal servitude, and

Somehow, miraculously, here you are.

“The dream and the hope of the slave.”

Slavery shattered Black families.

This was designed to cut us off at the roots, stunt our growth – explicit daily degradation:

You’z just a slave! No more no less.

For whites hearing this, it may evoke images of their ancestors who committed such acts. How exactly did they become capable of such every day cruelty…and live with it?

All must understand our roots in order to grow.

For slave descendants, we see survivors of a tremendously horrible system.

This includes both white and Black people.

Those who perpetrated, witnessed, resisted or fell victim to slavery’s atrocities.

We’re all descended from ‘slavery survivors’ too – our shared culture its remnants.

Of the myriad of emotions one feels in learning such facts, one is certainly pride.

Another is compassion.

We survived. And we now know better.

We rise.

We rise.

We rise.

[sigh]

Suggesting that we forget about slavery,

Or saying “Oh, but slavery was so long ago,”

Demands that we ignore our own people’s resilience, and will to live.

It’s akin to encouraging mass suicide.

For, to forget is to sever your own roots.

“Blood on the leaves, and blood at the root.”

And like any tree without roots, we’d wither and die, be crushed under our own weight.

Or, get chopped up and made useful.

Or, just left “for the sun to rot, for the tree to drop.”

Erasing history, turning away because of its discomfort, is a cult of death.

It moralizes its interest in decay.

To remember is to live, and celebrate life.

We must reckon with how our lives got here, to this day, to this very point.

Therefore, to learn is to know and continue to grow, for

A tree that’s not busy growing is busy dying.

The quest for roots is incredibly, powerfully, life-giving.

Find yours.

Call their names.

Knowledge further fertilizes freedom.

Know better. Do better.

Rise, like a breath of fresh air.

Another Lone Gunman #BlackenAsiaWithLove #SpOkenWoRd

A lone gunman killed numerous people at a public place in America.

Another lone gunman shot up a school, another a nightclub, and

Another killed a kid walking down the street.

A few years ago,

Another lone gunman shot up a movie premier, dressed as one of the film’s villains.

Another – armed with a badge-

Took a woman’s life after a routine traffic stop.

Plenty of his comrades routinely did the same.

Another lone gunman in blue, killed a kid playing in the park, and

Another shot a man who was reaching for his wallet as he’d demanded.

Another shot a man with his kid in the backseat, while his girlfriend live-streamed it, and

Another took 8 minutes and 46 seconds to kill again.

Another watched while it happened, while

Another kept the crowd at bay.

Another. And another, and

Last week, in another American city, another lone gunman murdered more.

The lone gunman in blue responsible for safely apprehending this latest lone gunman said: This poor lone gunman just had “a bad day.”

We bide our time till next week’s breaking news.