Home » Teaching (Page 6)

Category Archives: Teaching

Criminology is everywhere!

When I think back to thinking about choosing a degree, way back when, I remember thinking Criminology would be a good choice because it is specific in terms of a field: mainly the Criminal Justice System (CJS). I remember, naively, thinking once I achieved my degree I could go into the Police (a view I quickly abandoned after my first year of studies), then I thought I could be involved in the Youth Justice System in some capacity (again a position abandoned but this time after year 2). And in third year I remember talking to my partner about the possibility of working in prisons: Crime and Punishment, and Violence: from domestic to institutional (both year 3 modules) kicked that idea to the curb! I remember originally thinking Criminology was quite narrow and specific in terms of its focus and range: and oh my was I wrong!

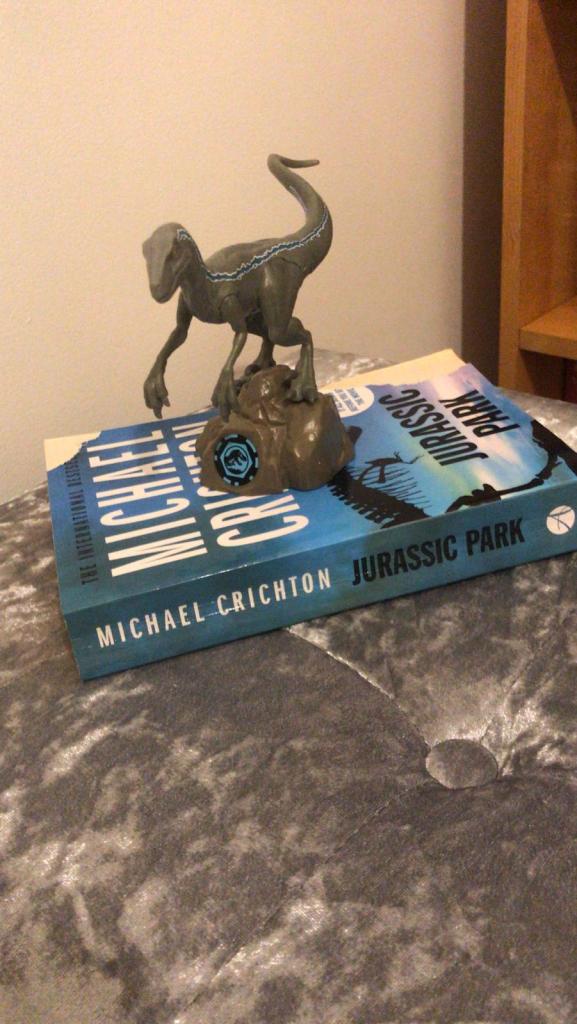

Whilst the skills acquired through any degree transcend to a number of career paths, what I find most satisfying about Criminology, is how it infiltrates everything! A recent example to prove my point which on the outside may have nothing to do with Criminology, when in actual fact it could be argued it has criminological concepts and ideas at its heart is the 2015 film: Jurassic World. It is no secret that I am a huge lover of Crichton novels but also dinosaurs. But what I hope to illustrate is how this film is excellent, not just in relation to dinosaur content: but also in relation to one of my interests in Criminology.

Jurassic World, for those of you who have not had the pleasure of viewing, focuses on the re-creation of a Jurassic Park, sporting new attractions, rides and dinosaurs in line with the 21st century. The Indominus Rex is a genetically modified hybrid which is ‘cooked-up’ in the lab, and is the focus of this film. Long story short, she escapes, hunts dinosaurs and people for sport, and is finally killed by a joint effort from the Tyrannosaurus, Blue the Velociraptor and the Mosasaurus: YAY! But what is particularly Criminological, in my humble opinion, is the focus and issues associated with the Indominus Rex being raised in isolation with no companionship in a steeled cage. Realistically, she lives her whole life in solitary confinement, and the rangers, scientists and management are then shocked that she has 0 social skills, and goes on a hunting spree. She is portrayed in the film as a villain of sorts, but is she really?

Recently in Violence: from domestic to institutional, we looked at the dangers and harms of placing individuals in solitary confinement or segregation. Jurassic World demonstrates this: albeit with a hybrid dinosaur which is fictitious. The dangers, and behaviours associated with the Indominus Rex are symbolic to the harms caused when we place individuals in prison. The space is too small, there is no interaction, empathy or relationships formed with the dinosaur apart from with the machine that feeds it. The same issues exist when we look at the prison system and it raises questions around why society is shocked when individuals re-offend. The Indominus Rex is a product of her surroundings and lack of relationships: there are some problematic genes thrown in there too but we shall leave that to one side for now.

There are a number of criminological issues evident in Jurassic World, (have a watch and see) and all of the Jurassic Park movies. Criminology is everywhere: in obvious forms and not so obvious forms. The issues with the prison system, segregation specifically, transcend to schools and hospitals, society in general and to dinosaurs in a fictional movie. Criminology, and with it critical thinking, is everywhere: even in the Lego Movie where everything is awesome! Conformity and deviance wrapped up in colourful bricks and catchy tunes: have a watch and see…

Some lessons from the lockdown

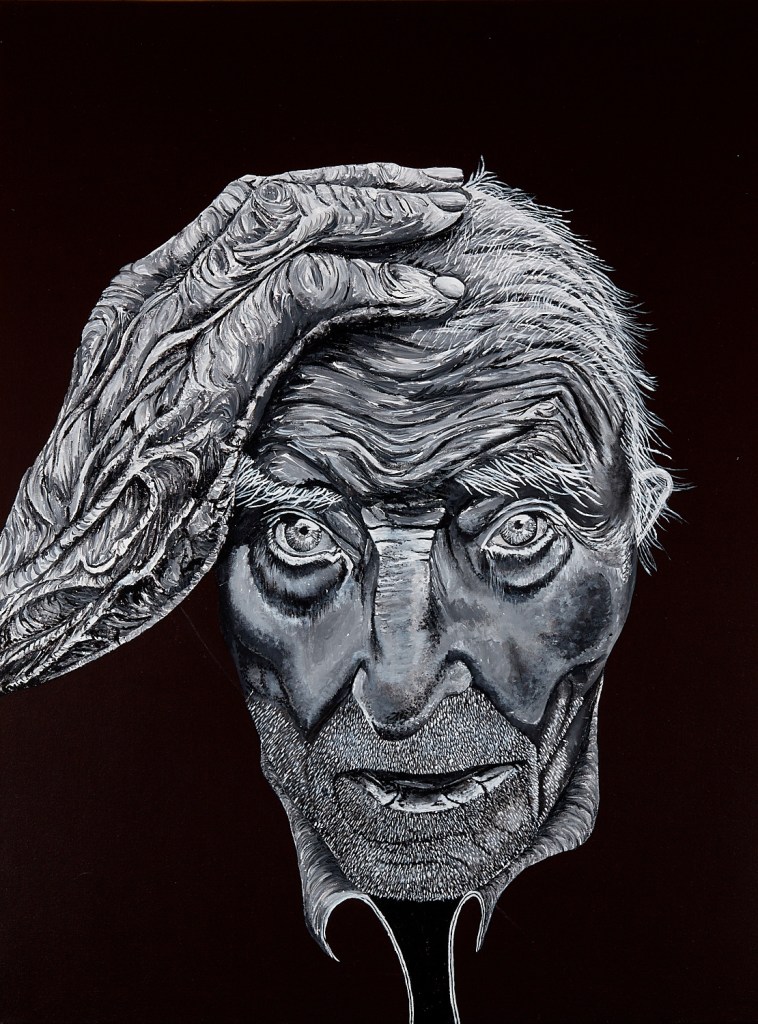

Koestler Arts (2019), Another Me: The Redwoods Centre (secure mental health unit), James Wood QC Silver Award for Portrait, 2019

In March 23, 2020, the UK went into lockdown. The advice given, albeit conflicting in parts, was clear. Do not leave your home unless absolutely necessary, banning all travel and social interactions. This unprecedented move forced people to isolate at home for a period, that for some people will come to an end, when the WHO announces the end of the pandemic. For the rest of us, the use of a face mask, sanitiser and even plastic gloves have become modern day accessories. The way the lockdown was imposed and the threat of a fine, police arrest if found outside one’s home sparked some people to liken the experience with that of detention and even imprisonment.

There was definite social isolation during the pandemic and there is some future work there to be done to uncover the impact it has had on mental health. Social distancing was a term added to our social lexicon and we discovered online meetings and working from home. Schools closed and parents/guardians became de facto teachers. In a previous blog entry, we talked about the issues with home schooling but suffice to say many of our friends and colleagues discovered the joys of teaching! On top of that a number of jobs that in the past were seeing as menial. Suddenly some of these jobs emerge as “key professions”

The first lesson therefore is:

Our renewed appreciation for those professions, that we assumed just did a job, that was easy or straightforward. As we shall be coming back eventually to a new normality, it is worth noting how easy it will be to assign any job as trivial or casual.

As online meetings became a new reality and working from home, the office space and the use of massive buildings with large communal areas seemed to remain closed. This is likely to have a future impact on the way business conduct themselves in the future.

Second lesson:

Given how many things had to be done now, does this mean that the multi occupancy office space will become redundant, pushing more work to be done from home. This will alter the way we divide space and work time.

During the early stages of the lockdown, some people asked for some reflection of the situation in relation to people’s experiences in prisons. The lockdown revealed the inequality of space. The reality is that for some families, space indicated how easy is to absorb the new social condition, whilst other families struggled. There is anecdotal information about an increase on mental health and stress caused from the intensive cohabitation. Several organisations raised the alarm that since the start of the lockdown there has been a surge in incidents of domestic violence and child abuse. The actual picture will become clearer of the impact the lockdown had on domestic violence in future years when comparisons can be drawn. None the less it reveals an important issue.

Third lesson:

The home is not always the safest place when dealing with a global pandemic. The inequality of space and the inequality in relationships revealed what need to be done in the future in order to safeguard. It also exposed the challenges working from home for those that have no space or infostructure to support it.

In the leading up to the lockdown many households of vulnerable people struggled to cope with family members shielding from the virus. These families revealed weaknesses in the welfare system and the support they needed in order to remain in lockdown. Originally the lack of support was the main issue, but as the lockdown continued more complex issues emerged, including the financial difficulties and the poverty as real factors putting families at risk.

Fourth lesson:

Risk is a wider concern that goes beyond personal and family issues. The lockdown exposed social inequality, poverty, housing as factors that increase the vulnerability of people. The current data on Covid-19 fatalities reveal a racial dimension which cannot longer be ignored.

During the lockdown, the world celebrated Easter and commemorated Mayday, with very little interaction whilst observing social distancing. At the end of May the world watched a man gasping for breath that died in police custody. This was one of the many times the term police brutality has related to the dead of another black life. People took to the streets, protested and toppled a couple of statues of racists and opened a conversation about race relations.

Fifth lesson:

People may be in lockdown, but they can still express how they feel.

So, whilst the lockdown restrictions are easing and despite having some measures for the time being, we are stepping into a new social reality. On the positive side, a community spirit came to the surface, with many showing solidarity to those next to them, taking social issues to heart and more people talked of being allies to their fellow man. It seems that the state was successful to impose measures that forced people indoors that borderline in totalitarianism, but people did accept them, only as a gesture of goodwill. This is the greatest lesson of them all in lockdown; maybe people are out of sight, appear to be compliant in general but they are still watching, taking note and think of what is happening. What will happen next is everyone’s guess.

When I grow up what will I be?

Wherever I go in life, whatever I do, as long as I am helping others and making a positive difference, I will be happy”

For many years, that has been my take on looking for jobs – helping people, and making a positive difference.

What will I do with my life? Where will life lead me? I’ll say my prayers, and find out!

As a child (between 5-9 years old), I wanted to be a nurse; I have a caring nature, and love helping people! Imagining myself in a nurse’s uniform, and putting bandages on patients and making them better, was something I dreamed about.

Life moves forward, and at the age of 13 I wanted to be so much!

I considered becoming a teacher of either English or Religious Studies. At 13, I loved English and learning about all world faiths. It fascinated me! My teacher had a degree and masters from Oxford University; and I absorbed everything I could! Religious Studies was my favourite subject (alongside art, drama and English) I also had my first, most profound spiritual experience, deepening my Catholic faith (written in more detail in chapter 1 of Everyday Miracles).

My hobbies included reading, writing and drawing. Throughout my teenage years, I devoured the Harry Potter books, the Lord of the Rings books, and Phillip Pullman’s His Dark Materials books. I had a library card, and would borrow books from the library in my village and would read regularly at home. I wanted to be an artist and author, and would often write poetry and short stories, and kept a sketchbook to do drawings in. I dreamed of being a published author, and to be an artist – however, these were seemingly beyond my reach. I prayed to God, that I would be able to fulfil these life ambitions one day.

Alongside of this, I also did some charity work – any change that I got from my lunches, I would put in an empty coffee jar and save them up. I was given the rather cruel nickname, ‘penny picker’, which resulted in bullying from people across different year groups, because I picked up pennies off the floor and put them in my charity pot. Though I did get a mention in the school newsletter stating that the money I raised amounted to quite a large sum, and went to CAFOD, and a homeless charity. I have always done charity work, and still do charity work today!

In school, there were 2 sets in each year; the A-band and the B-band. The A-band were the high academic performers, and those who got high grades. The B-band was the lower set… the set which I was in… This meant that when it came to picking GCSEs, I could only choose 2, not 3, which the A-band students were able to do.

In my Citizenship and Religious studies lessons, I began learning more about the globalized world, human rights, and social issues. Here, I learned in great detail about slavery (slightly covered in history too), prejudice and discrimination, the Holocaust, and 3rd world issues, such as extreme poverty, deprivation, and lack of basic human necessities, such as water, food and sanitation. We even touched upon the more horrific human rights abuses such as extraordinary rendition, religious persecution, torture, and rape and sexual violence.

My ambitions began to evolve more, and I dreamed of becoming a lawyer and even a judge. I wanted to serve justice, make communities safer, and to do more to combat these issues. With my soft heart, and a love of helping people, I knew that being a lawyer would help with doing this!

Moving forward to Year 10; choosing my GCSEs…. I spoke with one of the school heads, and asked for advice. I was still adamant on being a lawyer, and so was advised to do drama and history. Drama as it would boost my confidence, public speaking and expressive skills. History, because of the analytical thinking and examination of evidence that lawyers need when presenting their arguments. I was very happy with this! I loved drama and I enjoyed history – both the teachers were great and supportive!

At the age of 15, I was diagnosed with Asperger Syndrome – this explained so much about me and my idiosyncrasies. Ironically, it was my drama and my history teacher who picked up on it, due to my odd gait, social skills, and how I processed information. At parents’ evening, both teachers discussed with my mum about the diagnosis, and getting support. It was a big shock when I spoke with each of my teachers individually about the diagnosis.

At the end of doing my GCSEs, I was a pretty average student with mostly C grades. When it came to picking A-levels, I was unable to to the subjects that I really wanted to do…. Philosophy, Theology, Law and Psychology…. After a few weeks of battling and trying to get onto a course that would accept me, I ended up doing Travel and Tourism, A-level Media, Applied Sciences and Forensics (which had a criminology module), and, in Year 13, I took on an Extended Project, to boost my chances of getting into university.

I felt somewhat disillusioned… I’m studying courses that will only accept me because of my grades – an odd combination, but a chance to learn new things and learn new skills! In my mind, I wondered what I would ever do with myself with these qualifications…

Deciding to roll with it, I went along. I was much more comfortable in my Sixth Form years as I learned to embrace my Asperger’s, and started being included in different socials and activities with my peers.

Those 2 years flew by, and during my science course, when I did the criminology unit, I was set on studying that joint honors at a university. Criminology gripped me! I loved exploring the crime rates in different areas, and why crime happens (I had been introduced briefly to Cesare Lombroso, and the Realist theories). I have always loved learning.

Fast forward, I decided to go to Northampton University to do Criminology and Education, and even had the hope that I may be able to get a teaching job with the education side. However, due to an education module no longer being taught, I majored in Criminology.

However, in my second year of studies, I did a placement at a secondary special needs college, and helped the children with their learning! All the children would have a day at a vocational training centre doing carpentry, arts and crafts, and other hands on and practical courses. Back in their classrooms, they had to write a log of what they learned. The students I helped were not academic, and so I would write questions on the board to guide them with their log writing, and would write words that they struggled to spell – my opportunity to help students with their education! Later in life, I worked as a Support Worker for students with additional needs at both Northampton, and Birmingham City University, so still learning whilst helping others.

July 2015, I graduated with a 2:1 in my degree, and I had been encouraged to do an LLM in International Criminal Law and Security – a degree in law! It was unreal! From being told I could not do A-level law, here, I was able to do a masters in law! I applied for the Santander Scholarship, and got enough money to cover my course and some living costs – basically, a Masters degree for free!

During those 2 years of being a part time post graduate, I set up and ran the Uni-Food Bank Team and continued with running Auto-Circle Spectrum Society. January 2016 saw a downward dive in my mental health and I was diagnosed with severe depression (When the Darkness Comes).

I learned to cope and found my own way of healing myself through art and painting (which I later began painting on canvasses and sold at arts and crafts fayres).

February 2018 – I graduate with my LLM; the first on my dad’s side of the family to go to university, and on my mum’s side, the first to have a masters’ degree.

Going back to the question of this blog; When I grow up, what will I be?

I will be everything that I ever wanted to be! I am now a published author (mentioned at the start of the blog), have done freelance writing and art (everything I have written on every platform used can be accessed here: Blog Home Page: Other Writing Pieces)! I got a degree in Criminology with Education, and a Masters degree in International Criminal Law and Security!

I have have utilised my knowledge of human rights to fight for the rights of Persecuted Christians, political and social activists, and write to someone on death row too! (Serving Our Persecuted Brothers and Sisters Globally, I See You, Prisoners of Conscience, Within Grey Walls

I still do loads of charity work, and support my local food bank along the side too! (Brain Tumor Research; Helping Those in Need)

It’s safe to say that God answered every single one of my prayers, and even gave me strength in some circumstances!

Currently, I am working as the administrator of an an addiction recovery unit in my home village! A job I thoroughly enjoy – it is challenging, my colleagues are the funniest bunch I have ever met! I have learned so much, and am thriving!

Most importantly, as I’ve grown up, I’ve learned to be happy, learned to overcome all odds that are against me, and to always help others regardless of the circumstance. I’ve learned to be compassionate and strong ❤

Teaching, Technology, and reality

I’m not a fan of technology used for communication for the most part, I’d rather do things face to face. But, I have to admit that at this time of enforced lockdown technology has been to a large extent our saviour. It is a case of needs must and if we want to engage with students at all, we have to use technology and if we want to communicate with the outside world, well in the main, its technology.

However, this is forced upon us, it is not a choice. Why raise this, well let me tell you about my experiences of using technology and being shut at home! Most, if not all my problems, probably relate to broadband. It keeps dropping out, sometimes I don’t notice, that is until I go to save my work or try to add the final comment to my marking. I know other colleagues have had the same problem. Try marking on Turnitin only to find that nearly all of your feedback has just disappeared in a flash. Try talking to colleagues on Webex and watch some of them disappearing and reappearing. Sometimes you can hear them, sometimes you can’t. And isn’t it funny when there is a time lag, a Two Ronnies moment when the question before the last is answered. ‘You go, no you go’, we say as we all talk over each other because the social cues relied on in face to face meetings just aren’t there. I’ve tried discussion boards with students, it’s not like WhatsApp or Messenger or even text. It is far more staid than that. Some students take part, but most don’t and that in a module where attendance in class before the shutdown was running at over seventy per cent. I’m lucky to get 20% involved in the discussion board. Colleagues using Collaborate tell me a similar tale, a tale of woe where only a few students, if any appear. Six hours of emptiness, thumb twiddling and reading, that’s the lecturer, not the students.

Now I don’t know whether my problems with the internet are resultant of the increased usage across the country, or just in my area. I suspect not because I had problems before the lockdown. I live in a village and whilst my broadband package promises me, and delivers brilliant broadband speed at times, it is inconsistent, frequently inexplicably dropping out for a minute or two. It is frustrating at times, even demoralising. I have a very good laptop (supplied by the university) and it is hardwired in, so not reliant on Wi-Fi, but it makes little difference. I suspect the problems could be anywhere in the broadband ether. It could be at the other end, the university, it could be at Turnitin for instance or maybe its somewhere in a black hole in the middle. Who knows, and I increasingly think, who cares? When my broadband disappeared for a whole day, a colleague suggested that I could tether my phone. A brilliant idea I thought as our discussion became distorted and it sounded like he was talking to me from a goldfish bowl. I guess the satellite overhead moved and my signal gradually disappeared. I can tell you now that my mobile phone operator is the only one that provides decent coverage in my area. Tethered to a goldfish bowl, probably not a solution, but thanks anyway.

If I suffer from IT issues, then what about students? We are assured that those that live on campus have brilliant Wi-Fi but does this represent the majority of our student body? Not usually and certainly not now. Do they all have good laptops; do they all have a decent Wi-Fi package? I hazard a guess, probably not. But even if what they have is on par with what I have available to me could they not also be encumbered with the same problems? We push technology as the way forward in education but don’t bother to ask the end user about their experience in using it. I can tell you from student feedback that many don’t like Collaborate, find the discussion boards difficult to engage with and some are completely demotivated if they cannot attend physical classes. That’s not to say that all students feel this way, some like recorded lectures as it gives them the opportunity to watch it at their leisure, but many don’t take that final step of actually watching it. They intend to, but don’t for whatever reason. Some like the fact that they can get books electronically, but many don’t, preferring to read from a hard copy. Even browsing the shelves in the library has for some, a mystical pleasure.

I’ll go back to the beginning, technology has undoubtedly been our saviour at this time of lockdown, but wouldn’t it be a real opportunity to think about teaching and technology after this enforced lockdown? Instead of assuming all students are technology savvy or indeed, want to engage with technology regardless of what it is, should we not ask them what works for them. Instead of telling staff what they can do with technology, e.g. you can even remotely mark students’ work on a Caribbean island, should we not ask staff what works? Let’s change the negative narrative, “you’re not engaging with technology”, to the positive what works in teaching our students and how might technology help in that. Note I say our students, not other students at other universities or some pseudo student in a theoretical vacuum. We should simply be asking what is best for our students and a starting point might be to ask them and those that actually teach them.