Home » Probation

Category Archives: Probation

A Criminal Called Bob

It was years ago that Bob was born in St. Mary’s Hospital. His mum delivered a relatively healthy baby that she called Robert, after her father despite kicking her out when he found out that she was pregnant from a casual encounter. Bob’s early memory was of a pain in the arm in a busy place he could not remember what it was. His mother was grabbing his arm an early sign that he was unwanted. He would remember many of these events becoming part of everyday life. He remembers one day a stern looking woman came to the place he was living with his mother and take him away. This was the last time he would ever see his mother; he was 5 or 6. A few years afterwards his mother will die from a bad heart. Later, he would find out it was drugs related.

The stern looking lady will take him to another place to live with a family. One of many that he would be placed in. At first, he tried to get to know the hosts but soon it became difficult to keep track. He also lost track of how many times he moved around. There were too many to count but the main memory was of fear going into a place he did not know to stay with people who treated him as an inconvenience. He owned nothing but a bin bag with a few clothes and people will always comment on how scruffy he looked. He remembers discovering some liquorice allsorts in a drawer with the kid he was sharing the room with. He cannot forget the beating he got for eating some of them. The host was very harsh, and they used the belt on him.

School was hell for Bob. As he moved from place to place the schools also changed. The introduction to the class was almost standard. Bob is joining us from so and so and although he lives in foster care, I hope you will be making him feel welcomed…and welcomed he was. The bullying was relentless so was the name calling and the attacks. On occasion he would meet an aloof man who was his “designated tutor”. His questions were abrupt and focused only if he was behaving, if he was making any trouble, if he did as was told. It was hardly ever about education or any of his needs. He remembers going to see him once with a bruised eye to be asked “what did you do?”

And he did a lot! Early on he learned that in order not to go hungry he must hide food away. If he was to meet a new person, he had to show them that he is cannot be taken for granted, he needed to show them he can handle himself. Sometime during his early teenage years his greeting gesture was a headbutt. Violence was a clear vehicle for communication. One person is down the other is up. This became a language he became prolific in. He could read a room quickly and in later years be able to assess the person opposite. If he can take him or not!

The truth that others kept talking about around him became a luxury and an unnecessary situation. Lying about things got him to avoid punishment and any consequences to any of his actions. The only problem was when he was get caught lying. The consequences were dire. So, what he needed to do was to become very good at it. He did. He could lie looking people straight in the eye and not even blink about it.

Later in life he discovered this was an amazing talent to possess. It was useful when he was stealing from shops, it was good when people asking him for the truth, it was profitable when his lies covered other people’s crimes. Before he turned 18, he was an experienced thief and a creative liar. His physique allowed him to take to violence should anyone was to question his “honesty”. When he was 15, he discovered that a combination of cider and acid gives him such a buzz. To mute his brain and to relax his body even for little was so welcomed. This habit became one of his most loyal relationships in his life.

In prison he didn’t go until he was 22 but he went to a young offender’s institution at the age of 17 for GBH. The “victim” was a former friend who stole some of his gear. That really angered him; even days after the event in court he was still outraged with the theft. He was still making threats that he will find him and kill him, in some very graphic descriptions! The court sought no other way but to send him away. From the age of 22 he would become a “frequent flyer” of the prison estate! A long list of different sentences ranging from everything on offer. Usually repeated in pattern; fine, community sentence, prison….and back again! By the time he was 35 he had been in prison for more than 8 years collectively. He did plenty of offender management courses and met a variety of probation and prison officers, well-meaning and not so good. Some tried to help, and others couldn’t care but all of them fade in the background.

Now at the ripe age of 45 he is out of the prison, and he is sofa surfing and claiming universal credit. He gets nothing because he has unpaid fines, so he is struggling financially. In prison he did a barista apprenticeship, but he cannot find any work. As it stands, he is very likely to be recalled back to prison, if the cold weather doesn’t claim him first.

In context, there are some lives that are never celebrated or commemorated. There are people who exist but virtually no one recognises their existence. Their lives are someone else’s inconvenience and in a society that prioritises individual achievement and progression they have none. Bob is a fictional character. His name and circumstances are made up but form part of a general criminological narrative that identifies criminality through the complexity of social circumstance.

Beyond education…

In a previous blog I wrote about the importance of going through HE as a life changing process. The hard skills of learning about a discipline and the issues, debates around it, is merely part of the fun. The soft skills of being a member of a community of people educated at tertiary level, in some cases, outweigh the others, especially for those who never in their lives expected to walk through the gates of HE. For many who do not have a history in higher education it is an incredibly difficult act, to move from differentiating between meritocracy to elitism, especially for those who have been disadvantaged all their lives; they find the academic community exclusive, arrogant, class-minded and most damning, not for them.

The history of higher education in the UK is very interesting and connected with social aspiration and mobility. Our University, along with dozens of others, is marked as a new institution that was created in a moment of realisation that universities should not be exclusive and for the few. In conversation with our students I mentioned how as a department and an institution we train the people who move the wheels of everyday life. The nurses in A&E, the teachers in primary education, the probation officers, the paramedics, the police officers and all those professionals who matter, because they facilitate social functioning. It is rather important that all our students understand that our mission statement will become their employment identity and their professional conduct will be reflective of our ability to move our society forward, engaging with difficult issues, challenging stereotypes and promoting an ethos of tolerance, so important in a society where violence is rising.

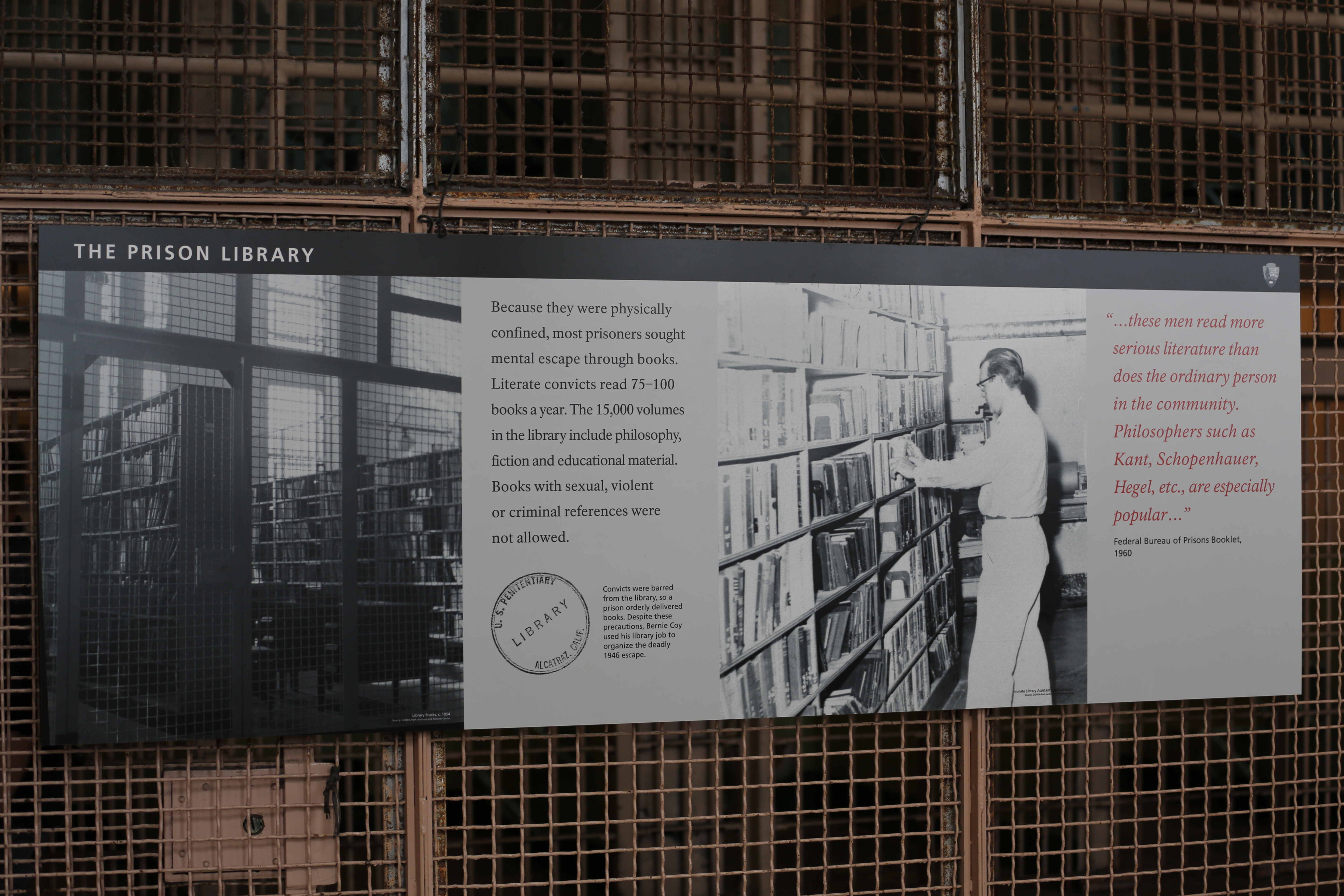

This week we had our second celebration of our prison taught module. For the last time the “class of 2019” got together and as I saw them, I was reminded of the very first session we had. In that session we explored if criminology is a science or an art. The discussion was long, and quite unexpected. In the first instance, the majority seem to agree that it is a social science, but somehow the more questions were asked, the more difficult it became to give an answer. What fascinates me in such a class, is the expectation that there is a clear fixed answer that should settle any debate. It is little by little that the realisation dawns; there are different answers and instead of worrying about information, we become concerned with knowledge. This is the long and sometimes rocky road of higher education.

Our cohort completed their studies demonstrating a level of dedication and interest for education that was inspiring. For half of them this is their first step into the world of HE whilst the other half are close to heading out of the University’s door. It is a great accomplishment for both groups but for the first who may feel they have a long way to go, I will offer the words of a greater teacher and an inspiring voice in my psyche, Cavafy’s ‘The First Step’

Even this first step

is a long way above the ordinary world.

To stand on this step

you must be in your own right

a member of the city of ideas.

And it is a hard, unusual thing

to be enrolled as a citizen of that city.

Its councils are full of Legislators

no charlatan can fool.

To have come this far is no small achievement:

what you have done already is a glorious thing

Thank you for entering this world. You earn it and from now on do not let others doubt you. You can do it if you want to. Education is there for those who desire it.

C.P. Cavafy, (1992) Collected Poems, Translated by Edmund Keeley and Philip Sherrard, Edited by George Savidis, Revised Edition, Princeton University Press, Princeton.

CRCs: Did we really expect them to work?

For those of you who follow changes in the Criminal Justice System (CJS) or have studied Crime and Justice, you will be aware that current probation arrangements are based on the notion of contestability, made possible by the Offender Management Act 2007 and fully enacted under the Offender Rehabilitation Act 2014. What this meant in practice was the auctioning off of probation work to newly formed Community Rehabilitation Companies (CRCs) in 2015 (Davies et al, 2015). This move was highly controversial and was strongly opposed by practitioners and academics alike who were concerned that such arrangements would undermine the CJS, result in a deskilled probation service, and create a postcode lottery of provision (Raynor et al., 2014; Robinson et al., 2016). The government’s decision to ignore those who may be considered experts in the field has had perilous consequences for those receiving the services as well as the service providers themselves.

Picking up on @manosdaskalou’s theme of justice from his June blog and considering the questions overhanging the future sustainability of the CRC arrangements it is timely to consider these provisions in a little more detail. In recent weeks I have found myself sitting on a number of probation or non-CPS courts where I have witnessed first-hand the inadequacies of the CRC arrangements and potential injustices faced by offenders under their supervision. For instance, I have observed a steady increase in applications from probation, or more specifically CRCs, to have community orders adjusted. While such requests are not in themselves unusual, the type of adjustment or more specifically the reason behind the request, are. For example, I have witnessed an increase in requests for the Building Better Relationships (BBR) programme to be removed because there is insufficient time left on the order to complete it, or that the order itself is increased in length to allow the programme to be completed[1]. Such a request raises several questions, firstly why has an offender who is engaged with the Community Order not been able to complete the BBR within a 12-month, or even 24-month timeframe? Secondly, as such programmes are designed to reduce the risk of future domestic abuse, how is rehabilitation going to be achieved if the programme is removed? Thirdly, is it in the interests of justice or fairness to increase the length of the community order by 3 to 6 month to allow the programme to be complete? These are complex questions and have no easy answer, especially if the reason for failing to complete (or start) the programme is not the offenders fault but rather the CRCs lack of management or organisation. Where an application to increase the order is granted by the court the offender faces an injustice in as much as their sentencing is being increased, not based on the severity of the crime or their failure to comply, but because the provider has failed to manage the order efficiently. Equally, where the removal of the BBR programme is granted it is the offender who suffers because the rehabilitative element is removed, making punishment the sole purpose of the order and thus undermining the very reason for the reform in the first place.

Whilst it may appear that I am blaming the CRCs for these failings, that is not my intent. The problems are with the reform itself, not necessarily the CRCs given the contracts. Many of the CRCs awarded contracts were not fully aware of the extent of the workload or pressure that would come with such provisions, which in turn has had a knock-on effect on resources, funding, training, staff morale and so forth. As many of these problems were also those plaguing probation post-reform, it should come as little surprise that the CRCs were in no better a position than probation, to manage the number of offenders involved, or the financial and resource burden that came with it.

My observations are further supported by the growing number of news reports criticising the arrangements, with headlines like ‘Private probation firms criticised for supervising offenders by phone’ (Travis, 2017a), ‘Private probation firms fail to cut rates of reoffending’ (Savage, 2018), ‘Private probation firms face huge losses despite £342m ‘bailout’’ (Travis, 2018), and ‘Private companies could pull out of probation contracts over costs’ (Travis, 2017b). Such reports come as little surprise if you consider the strength of opposition to the reform in the first place and their justifications for it. Reading such reports leaves me rolling my eyes and saying ‘well, what did you expect if you ignore the advice of experts!’, such an outcome was inevitable.

In response to these concerns, the Justice Committee has launched an inquiry into the Government’s Transforming Rehabilitation Programme to look at CRC contracts, amongst other things. Whatever the outcome, the cost of additional reform to the tax payer is likely to be significant, not to mention the impact this will have on the CJS, the NPS, and offenders. All of this begs the question of what the real intention of the Transforming Rehabilitation reform was, that is who was it designed for? If it’s aim was to reduce reoffending rates by providing support to offenders who previously were not eligible for probation support, then the success of this is highly questionable. While it could be argued that more offenders now received support, the nature and quality of the support is debatable. Alternatively, if the aim was to reduce spending on the CJS, the problems encountered by the CRCs and the need for an MoJ ‘bail out’ suggests that this too has been unsuccessful. In short, all that we can say about this reform is that Chris Grayling (the then Home Secretary), and the Conservative Government more generally have left their mark on the CJS.

[1] Community Orders typically lasts for 12 months but can run for 24 months. The BBR programme runs over a number of weeks and is often used for cases involving domestic abuse.

References:

Davies, M. (2015) Davies, Croall and Tyrer’s Criminal Justice. Harlow: Pearson.

Raynor, P., Ugwudike, P. and Vanstone, M. (2014) The impact of skills in probation work: A reconviction study. Criminology and Criminal Justice, 14(2), pp.235–249.

Robinson, G., Burke, L., and Millings, M. (2016) Criminal Justice Identities in Transition: The Case of Devolved Probation Services in England and Wales. British Journal of Criminology, 56(1), pp.161-178.

Savage, M. (2018) Private probation firms fail to cut rates of reoffending. Guardian [online]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2018/feb/03/private-firms-fail-cut-rates-reoffending-low-medium-risk-offenders [Accessed 6 July 2018].

Travis, A. (2017a) Private probation firms criticised for supervising offenders by phone. Guardian [online]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2017/dec/14/private-probation-firms-criticised-supervising-offenders-phone [Accessed 6 July 2018].

Travis, A. (2017b) Private companies could pull out of probation contracts over costs. Guardian [online]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2017/mar/21/private-companies-could-pull-out-of-probation-contracts-over-costs [Accessed 6 July 2018].

Travis, A. (2018) Private probation firms face huge losses despite £342m ‘bailout’. Guardian [online]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2018/jan/17/private-probation-companies-face-huge-losses-despite-342m-bailout [Accessed 6 July 2018].

Graduation: the end of the beginning?

Helen is an Associate Lecturer teaching on modules in years 1 and 3.

I joined the University of Northampton as an associate lecturer in 2009, teaching at first on the Offender Management foundation degree and then joining the Criminology team, although I had been a visiting lecturer in Criminology for a number of years prior to that. I am sorry that a prior commitment means that I am unable to join you for the Big Criminology Reunion, although the occasion has inspired me to reflect on the professional journey that starts with graduation.

Last week I received an e-mail from a former student in the 2010 Offender Management cohort. She is just about to qualify as a probation officer and she was asking for advice about giving evidence at Parole Board hearings. It was great to think back, to remember what a vibrant and enthusiastic student she was, and to project forwards; perhaps I’ll see her at an oral hearing soon. She will probably make an excellent probation officer, and the fact that she is asking for advice before she even starts is evidence of that. She will possibly be the first of our offender management students to become an offender manager!

A couple of years ago I was at a Parole Hearing at HMYOI Aylesbury where I was very impressed by the evidence of the trainee psychologist. She had prepared a clear, concise but thorough and analytical report on the prisoner and she gave her oral evidence confidently and thoughtfully. After the end of the hearing, she popped back in to tell me that she had been initially inspired to take up prison psychology after hearing my guest lecture on Manos’ Forensic Psychology module. I saw her again earlier this year and she’s still doing a great job!

For undergraduates, completing a degree, submitting a dissertation, putting the pen down at the end of the last exam and then graduating with friends, seems like the end of a long and arduous process. And of course it is! But as the stories above show, it is also just the beginning. Just the beginning of a professional journey which may or may not involve direct application of the subjects covered on the course. Not all our students become probation officers or prison psychologists or academic criminologists, but they will take something of what they learn out into the world with them. It may be a more critical way of digesting the news, a wider appreciation of the social forces that shape our world, a readiness to reflect and question and see the world from different perspectives. All of that will help them on their journey. I hope that you all have a great time at the reunion and that as you compare each other’s journeys you have fond memories of the degree course that seemed a marathon at the time but was really only the first step!