Home » Articles posted by Paula Bowles (Page 8)

Author Archives: Paula Bowles

Goodbye 2018….Hello 2019

Now that the year is almost over, it’s time to reflect on what’s gone before; the personal, the academic, the national and the global. This year, much like every other, has had its peaks and its troughs. The move to a new campus has offered an opportunity to consider education and research in new ways. Certainly, it has promoted dialogue in academic endeavour and holds out the interesting prospect of cross pollination and interdisciplinarity.

On a personal level, 2018 finally saw the submission of my doctoral thesis. Entitled ‘The Anti-Thesis of Criminological Research: The case of the criminal ex-servicemen,’ I will have my chance to defend this work, so still plenty of work to do.

For the Criminology team, we have greeted a new member; Jessica Ritchie and congratulated the newly capped Dr Susie Atherton. Along the way there may have been plenty of challenges, but also many opportunities to embrace and advance individual and team work. In September 2018 we greeted a bumper crop of new apprentice criminologists and welcomed back many familiar faces. The year also saw Criminology’s 18th birthday and our first inaugural “Big Criminology Reunion”. The chance to catch up with graduates was fantastic and we look forward to making this a regular event. Likewise, the fabulous blog entries written by graduates under the banner of “Look who’s 18” reminded us all (if we ever had any doubt) of why we do what we do.

Nationally, we marked the centenaries of the end of WWI and the passing of legislation which allowed some women the right to vote. This included the unveiling of two Suffragette statues; Millicent Fawcett and Emmeline Pankhurst. The country also remembered the murder of Stephen Lawrence 25 years earlier and saw the first arrests in relation to the Hillsborough disaster, All of which offer an opportunity to reflect on the behaviour of the police, the media and the State in the debacles which followed. These events have shaped and continue to shape the world in which we live and momentarily offered a much-needed distraction from more contemporaneous news.

For the UK, 2018 saw the start of the Grenfell Tower Inquiry, the Windrush scandal, the continuing rise of the food bank, the closure of refuges, the iniquity of Universal Credit and an increase in homelessness, symptoms of the ideological programmes of “austerity” and maintaining a “hostile environment“. All this against a backdrop of the mystery (or should that be mayhem) of Brexit which continues to rumble on. It looks likely that the concept of institutional violence will continue to offer criminologists a theoretical lens to understand the twenty-first century (cf. Curtin and Litke, 1999, Cooper and Whyte, 2018).

Internationally, we have seen no let-up in global conflict, the situation in Afghanistan, Iraq, Myanmar, Syria, Yemen (to name but a few) remains fraught with violence. Concerns around the governments of many European countries, China, North Korea and USA heighten fears and the world seems an incredibly dangerous place. The awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to Denis Mukwege and Nadia Murad offers an antidote to such fears and recognises the powerful work that can be undertaken in the name of peace. Likewise the deaths of Professor Stephen Hawking and Harry Leslie Smith, both staunch advocates for the NHS, remind us that individuals can speak out, can make a difference.

To my friends, family, colleagues and students, I raise a glass to the end of 2018 and the beginning of 2019:

‘Let’s hope it’s a good one, without any fear’ (Lennon and Ono, 1974).

References:

Cooper, Vickie and Whyte, David, (2018), ‘Grenfell, Austerity and Institutional Violence,’ Sociological Research Online, 00, 0: 1-10

Curtin, Deane and Litke, Robert, (1999) (Eds), Institutional Violence, (Amsterdam: Rodopi)

Lennon, John and Ono, Yoko, (1974) Happy Xmas (War is Over), [CD], Recorded by John and Yoko: Plastic Ono Band in Shaved Fish. PCS 7173, [s.l.], Apple

Have you been radicalised? I have

On Tuesday 12 December 2018, I was asked in court if I had been radicalised. From the witness box I proudly answered in the affirmative. This was not the first time I had made such a public admission, but admittedly the first time in a courtroom. Sounds dramatic, but the setting was the Sessions House in Northampton and the context was a Crime and Punishment lecture. Nevertheless, such is the media and political furore around the terms radicalisation and radicalism, that to make such a statement, seems an inherently radical gesture.

So why when radicalism has such a bad press, would anyone admit to being radicalised? The answer lies in your interpretation, whether positive or negative, of what radicalisation means. The Oxford Dictionary (2018) defines radicalisation as ‘[t]he action or process of causing someone to adopt radical positions on political or social issues’. For me, such a definition is inherently positive, how else can we begin to tackle longstanding social issues, than with new and radical ways of thinking? What better place to enable radicalisation than the University? An environment where ideas can be discussed freely and openly, where there is no requirement to have “an elephant in the room”, where everything and anything can be brought to the table.

My understanding of radicalisation encompasses individuals as diverse as Edith Abbott, Margaret Atwood, Howard S. Becker, Fenner Brockway, Nils Christie, Angela Davis, Simone de Beauvoir, Paul Gilroy, Mona Hatoum, Stephen Hobhouse, Martin Luther King Jr, John Lennon, Primo Levi, Hermann Mannheim, George Orwell, Sylvia Pankhurst, Rosa Parks, Pablo Picasso, Bertrand Russell, Rebecca Solnit, Thomas Szasz, Oscar Wilde, Virginia Woolf, Benjamin Zephaniah, to name but a few. These individuals have touched my imagination because they have all challenged the status quo either through their writing, their art or their activism, thus paving the way for new ways of thinking, new ways of doing. But as I’ve argued before, in relation to civil rights leaders, these individuals are important, not because of who they are but the ideas they promulgated, the actions they took to bring to the world’s attention, injustice and inequality. Each in their own unique way has drawn attention to situations, places and people, which the vast majority have taken for granted as “normal”. But sharing their thoughts, we are all offered an opportunity to take advantage of their radical message and take it forward into our own everyday lived experience.

Without radical thought there can be no change. We just carry on, business as usual, wringing our hands whilst staring desperate social problems in the face. That’s not to suggest that all radical thoughts and actions are inherently good, instead the same rigorous critique needs to be deployed, as with every other idea. However rather than viewing radicalisation as fundamentally threatening and dangerous, each of us needs to take the time to read, listen and think about new ideas. Furthermore, we need to talk about these radical ideas with others, opening them up to scrutiny and enabling even more ideas to develop. If we want the world to change and become a fairer, more equal environment for all, we have to do things differently. If we cannot face thinking differently, we will always struggle to change the world.

For me, the philosopher Bertrand Russell sums it up best

Thought is subversive and revolutionary, destructive and terrible; thought is merciless to privilege, established institutions, and comfortable habits; thought is anarchic and lawless, indifferent to authority, careless of the well-tried wisdom of the ages. Thought looks into the pit of hell and is not afraid. It sees man, a feeble speck, surrounded by unfathomable depths of silence; yet it bears itself proudly, as unmoved as if it were lord of the universe. Thought is great and swift and free, the light of the world, and the chief glory of man (Russell, 1916, 2010: 106).

Reference List:

Russell, Bertrand, (1916a/2010), Why Men Fight, (Abingdon: Routledge)

‘The Problem We All Live With’

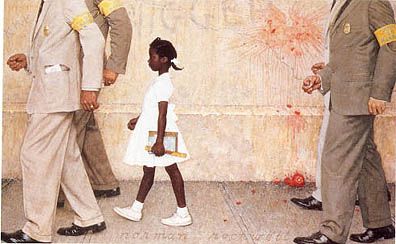

The title of this blog and the picture above relate to Norman Rockwell’s (1964) painting depicting Ruby Bridges on her way to school in a newly desegregated New Orleans. In over half a century, this picture has never lost its power and remains iconic.

Attending conferences, especially such a large one as the ASC, is always food for thought. The range of subjects covered, some very small and niche, others far more longstanding and seemingly intractable, cause the little grey cells to go into overdrive. So much to talk about, so much to listen to, so many questions, so many ideas make the experience incredibly intense. However, education is neither exclusive to the conference meeting rooms nor the coffee shops in which academics gather, but is all around. Naturally, in Atlanta, as I alluded to in my previous entry this week, reminders of the civil rights movement are all around us. Furthermore, it is clear from the boarded-up shops, large numbers of confused and disturbed people wandering the streets, others sleeping rough, that many of the issues highlighted by the civil rights movement remain. Slavery and overt segregation under the Jim Crow laws may be a thing of the past, but their impact endures; the demarcation between rich and poor, Black and white is still obvious.

The message of civil rights activists is not focused on beatification; they are human beings with all their failings, but far more important and direct. To make society fairer, more just, more humane for all, we must keep moving forward, we must keep protesting and we must keep drawing attention to inequality. Although it is tempting to revere brave individuals such as Ruby Bridges, Claudette Colvin, Martin Luther King Jr, Rosa Parks, Malcolm X to name but a few, this is not an outcome any of them ascribed to. If we look at Martin Luther King Jr’s ‘“The Drum Major Instinct” Sermon Delivered at Ebenezer Baptist Church’ he makes this overt. He urges his followers not to dwell on his Nobel Peace Prize, or any of his other multitudinous awards but to remember that ‘he tried’ to end war, bring comfort to prisoners and end poverty. In his closing words, he stresses that

If I can help somebody as I pass along,

If I can cheer somebody with a word or song,

If I can show somebody he’s traveling wrong,

Then my living will not be in vain.

If I can do my duty as a Christian ought,

If I can bring salvation to a world once wrought,

If I can spread the message as the master taught,

Then my living will not be in vain.

These powerful words stress practical activism, not passive veneration. Although a staunch advocate for non-violent resistance, this was never intended as passive. The fight to improve society for all, is not over and done, but a continual fight for freedom. This point is made explicit by another civil rights activist (and academic) Professor Angela Davis in her text Freedom is a Constant Struggle. In this text she draws parallels across the USA, Palestine and other countries, both historical and contemporaneous, demonstrating that without protest, civil and human rights can be crushed.

Whilst ostensibly Black men, women and children can attend schools, travel on public transport, eat at restaurants and participate in all aspects of society, this does not mean that freedom for all has been achieved. The fight for civil rights as demonstrated by #blacklivesmatter and #metoo, campaigns to end LGBT, religious and disability discrimination, racism, sexism and to improve the lives of refugees, illustrate just some of the many dedicated to following in a long tradition of fighting for social justice, social equality and freedom.

Theater of Forgiveness

A very powerful piece of writing

Hafizah Geter | Longreads | November 2018 | 32 minutes (8,050 words)

On Wednesday, October 24th, 2018, a white man who tried and failed to unleash his violent mission on a black church, fatally killed the next black people of convenience, Vickie Lee Jones, 67, and Maurice E. Stallard, 69, in a Jeffersontown, Kentucky Kroger. Today, I am thinking of the families and loved ones of Stallard and Jones, who the media reports, along with their grief, their anger, their lack of true recourse, have taken on the heavy work of forgiveness.

***

June 17, 2015, two hours outside my hometown, a sandy blonde-haired Dylann Roof walked into Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina. That night, Roof, surely looking like an injured wolf, someone already on fire, sat with an intimate group of churchgoers, and I have no doubt, was prayed for. If history repeats itself, then…

View original post 8,189 more words

Are we really free?

This year the American Society of Criminology conference (Theme: Institutions, Cultures and Crime) is in Atlanta, GA a city famous for a number of things; Mitchell’s novel, (1936), Gone with the Wind and the home of both Coca-Cola, and CNN. More importantly the city is the birthplace and sometime home of Dr Martin Luther King Jr and played a pivotal role in the Civil Rights Movement. Throughout the city there are reminders of King’s legacy, from street names to schools and of course, The King Center for Non-Violent Social Change.

This week @manosdaskalou and I visited the Center for Civil and Human Rights, opened in 2014 with the aim of connecting the American Civil Rights Movement, to broader global claims for Human Rights. A venue like this is an obvious draw for criminologists, keen to explore these issues from an international perspective. Furthermore, such museums engender debate and discussion around complex questions; such as what it means to be free; individually and collectively, can a country be described as free and why individuals and societies commit atrocities.

According to a large-scale map housed within the Center the world is divided up into countries which are free, partially free and not free. The USA, the UK and large swathes of what we would recognise as the western world are designated free. Other countries such as Turkey and Bolivia are classified as partially free, whilst Russia and Nigeria are not free. Poor Tonga receives no classification at all. This all looks very scientific and makes for a graphic illustration of areas of the world deemed problematic, but by who or what? There is no information explaining how different countries were categorised or the criteria upon which decisions were made. Even more striking in the next gallery is a verbatim quotation from Walter Cronkite (journalist, 1916-2009) which insists that ‘There is no such thing as a little freedom. Either you are all free, or you are not free.’ Unfortunately, these wise words do not appear to have been heeded when preparing the map.

Similarly, another gallery is divided into offenders and victims. In the first half is a police line-up containing a number of dictators, including Hitler, Pol Pot and Idi Amin suggesting that bad things can only happen in dictatorships. But what about genocide in Rwanda (just one example), where there is no obvious “bad guy” on which to pin blame? In the other half are interactive panels devoted to individuals chosen on the grounds of their characteristics (perceived or otherwise). By selecting characteristics such LGBT, female, migrant or refugee, visitors can read the narratives of individuals who have been subjected to such regimes. This idea is predicated on expanding human empathy, by reading these narratives we can understand that these people aren’t so different to us.

Museums such as the Center for Civil and Human Rights pose many more questions than they can answer. Their very presence demonstrates the importance of understanding these complex questions, whilst the displays and exhibits demonstrate a worldview, which visitors may or may not accept. More importantly, these provide a starting point, a nudge toward a dialogue which is empathetic and (potentially) focused toward social justice. As long as visitors recognise that nudge long after they have left the Center, taking the ideas and arguments further, through reading, thinking and discussion, there is much to be hopeful about.

In the words of Martin Luther King Jr (in his 1963, Letter from Birmingham Jail):

‘Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly’

Lest we forget

Today marks 100 years since the end of the First World War and commemorations will be taking place across the land. I will be overseas for much of the pomp and circumstance, but the build-up each year appears to begin earlier and earlier. As a pacifist, I always find this time of year very troubling, particularly the focus on the Royal British Legion [RBL] poppy.

Most combatants (both axis and allies) in both world wars were conscripted, that is they were legislatively compelled into military uniform. This was also the case in the UK, with the passing of the Military Service Act, 1916, Military Training Act, 1939 and National Service Act, 1948 ensuring that men had little option but to spend a period of time in the military. Objections on the grounds of conscience were legally tolerated, although not always upheld. As I have written about previously, this was a particularly treacherous path to follow in WWI.

So, for many men* during the period of 1916-1960, military service was not a choice, thus it makes sense to talk about a society which owes a debt to these individuals for the sacrifice of their time, energy and in some cases, lives. Remember these men were removed from their jobs and their families, any aspirations had to be put on hold until after the war, and who knew when that was likely to occur?

Since 1960, military service in the UK has been on a voluntary basis, although, we can of course revisit criminological discussions around free will, to ascertain how freely decisions to enlist can truly be. Nevertheless, there is a substantive difference between servicemen during that period and those that opt for military service after that period. Such a distinction appears to pass by many, including the RBL, who are keen to commemorate and fetishize the serviceman as intrinsically heroic and worthy of society’s unquestioning support.

The decision to wear a poppy, whether RBL red or peace pledge union [ppu] white is a personal one. The former is seen as the official national symbol of commemoration, designed to recognise the special contribution of service personnel and their families. The latter is often attacked as an affront to British service personnel, although the ppu explicitly note that the white poppy represents everybody killed during warfare, including all military combatants and victims. It draws no distinctions across national borders, neither does it privilege the military over the civilian victims. These different motifs, each with their own specific narratives, pose the question of what it is as individuals and as a society we mean by ‘Lest we forget’.

- Do we want to remember those conscripted soldiers and swear that as a society we will not force individuals into the military, regardless of their personal viewpoints, desires, aspirations?

- Do we want to remember soldiers and swear that as a society we will not go to war again?

If it is the latter, we should take more notice of the work of RBL, who although coy about their relationships with arms dealers, accept a great deal of money from them (cf. Tweedy, 2015, BAE Systems, 2018). We should also consider the beautiful and poignant display at the Tower of London in 2014, entitled Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red (Cummins and Piper, 2014). The week after this display began to be dismantled, a dinner for arms dealers was held at the same venue. Whilst RBL is keen to deny that their poppy is partisan and political, it is evident that this little paper flower is not neutral. Discussions and arguments on social media have demonstrated that this motif can and is used as a battering ram to close down questions, anxieties and deliberation. Even more worrying is the rewriting of history, that WWI and WWII were won by British forces, neglecting that these were world wars, involving individuals; men, women and children, from all over the globe. This narrative seems to have attached itself to the furor around Brexit, “we saved Europe, they owe us”!

For me, on an extremely personal level, we should be looking to end war, not looking for ways in which to commemorate past wars.

*For more detail around the conscription of women during WWII see Nicholson (2007) and Elster and Sørensen (2010).

References

BAE Systems, (2018), ‘Supporting the Armed Forces,’ BAE Systems, [online]. Available from: https://www.baesystems.com/en-uk/our-company/corporate-responsibility/working-responsibly/supporting-communities/supporting-the-armed-forces [Last accessed 20 October 2018]

Cummins, Paul, (2016), ‘Important Notice,’ Paul Cummins Ceramics, [online]. Available from: https://www.paulcumminsceramics.com/important-notice/ [Last accessed 11 November 2016]

Cummins, Paul and Piper, Tom, (2014), Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red, [Ceramic Installation], (London: Tower of London)

Elster, Ellen and Sørensen, Majken Jul, (2010), ‘(Eds), Women Conscientious Objectors: An Anthology, (London: War Resisters’ International)

Military Service Act, 1916, (London: HMSO)

Military Training Act, 1939, (London: HMSO)

Milmo, Cahai, (2014), ‘The Crass Insensitivity’ of Tower’s Luxury Dinner for Arms Dealers, Days After Poppy Display, i-news, Thursday 27 November 2014, [online]. Available from: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/the-crass-insensitivity-of-tower-s-luxury-dinner-for-arms-dealers-days-after-poppy-display-9888507.html [Last accessed 27 November 2014]

National Service Act, 1948, (London: HMSO)

Nicholson, Hazel, (2007), ‘A Disputed Identity: Women Conscientious Objectors in Second World War Britain,’ Twentieth Century British History, 18, 4: 409-28

peace pledge union [ppu], (2018), ‘Remembrance & White Poppies,’ peace pledge union, [online]. Available from: https://ppu.org.uk/remembrance-white-poppies [Last accessed 11 November 2018]

Tweedy, Rod, (2015), My Name is Legion: The British Legion and the Control of Remembrance, (London: Veterans for Peace UK), [online]. Available from: http://vfpuk.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/my_name_is_legion-web.pdf [Last accessed 14 May 2017]

Questions, questions, questions…..

Over the last two weeks we have welcomed new and returning students to our brand-new campus. From the outside, this period of time appears frenetic, chaotic, and incredibly noisy. During this period, I feel as if I am constantly talking; explaining, indicating, signposting, answering questions and offering solutions. All of this is necessary, after all we’re all in a new place, the only difference is that some of us moved in before others. This part of my role has, on the surface, little to do with Criminology. However, once the housekeeping is out of the way we can move to more interesting criminological discussion.

For me, this focuses on the posing of questions and working out ways in which answers can be sought. It’s a common maxim, that within academia, there is no such thing as a silly question and Criminology is no exception (although students are often very sceptical). When you are studying people, everything becomes complicated and complex and of course posing questions does not necessarily guarantee a straightforward answer. As many students/graduates over the years will attest, criminological questions are often followed by yet more criminological questions… At first, this is incredibly frustrating but once you get into the swing of things, it becomes incredibly empowering, allowing individual mental agility to navigate questions in their own unique way. Of course, criminologists, as with all other social scientists, are dependent upon the quality of the evidence they provide in support of their arguments. However, criminology’s inherent interdisciplinarity enables us to choose from a far wider range of materials than many of our colleagues.

So back to the questions…which can appear from anywhere and everywhere. Just to demonstrate there are no silly questions, here are some of those floating around my head currently:

- This week I watched a little video on Facebook, one of those cases of mindlessly scrolling, whilst waiting for something else to begin. It was all about a Dutch innovation, the Tovertafel (Magic Table) and I wondered why in the UK, discussions focus on struggling to feed and keep our elders warm, yet other countries are interested in improving quality of life for all?

- Why, when with every fibre of my being, I abhor violence, I am attracted to boxing?

3. Why in a supposedly wealthy country do we still have poverty?

4. Why do we think boys and girls need different toys?

5. Why does 50% of the world’s population have to spend more on day-to-day living simply because they menstruate?

6. Why as a society are we happy to have big houses with lots of empty rooms but struggle to house the homeless?

7. Why do female ballroom dancers wear so little and who decided that women would dance better in extremely high-heeled shoes?

This is just a sample and not in any particular order. On the surface, they are chaotic and disjointed, however, what they all demonstrate is my mind’s attempt to grapple with extremely serious issues such as inequality, social deprivation, violence, discrimination, vulnerability, to name just a few.

So, to answer the question posed last week by @manosdaskalou, ‘What are Universities for?’, I would proffer my seven questions. On their own, they do not provide an answer to his question, but together they suggest avenues to explore within a safe and supportive space where free, open and academic dialogue can take place. That description suggests, for me at least, exactly what a university should be for!

And if anyone has answers for my questions, please get in touch….

Criminology: in the business of creating misery?

I’ve been thinking about Criminology a great deal this summer! Nothing new you might say, given that my career revolves around the discipline. However, my thoughts and reading have focused on the term ‘criminology’ rather than individual studies around crime, criminals, criminal justice and victims. The history of the word itself, is complex, with attempts to identify etymology and attribute ownership, contested (cf. Wilson, 2015). This challenge, however, pales into insignificance, once you wander into the debates about what Criminology is and, by default, what criminology isn’t (cf. Cohen, 1988, Bosworth and Hoyle, 2011, Carlen, 2011, Daly, 2011).

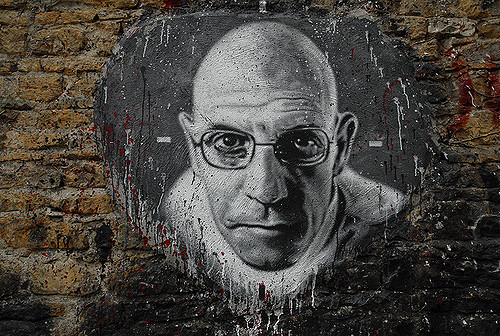

Foucault (1977) infamously described criminology as the embodiment of utilitarianism, suggesting that the discipline both enabled and perpetuated discipline and punishment. That, rather than critical and empathetic, criminology was only ever concerned with finding increasingly sophisticated ways of recording transgression and creating more efficient mechanisms for punishment and control. For a long time, I have resisted and tried to dismiss this description, from my understanding of criminology, perpetually searching for alternative and disruptive narratives, showing that the discipline can be far greater in its search for knowledge, than Foucault (1977) claimed.

However, it is becoming increasingly evident that Foucault (1977) was right; which begs the question how do we move away from this fixation with discipline and punishment? As a consequence, we could then focus on what criminology could be? From my perspective, criminology should be outspoken around what appears to be a culture of misery and suspicion. Instead of focusing on improving fraud detection for peddlers of misery (see the recent collapse of Wonga), or creating ever increasing bureaucracy to enable border control to jostle British citizens from the UK (see the recent Windrush scandal), or ways in which to excuse barbaric and violent processes against passive resistance (see case of Assistant Professor Duff), criminology should demand and inspire something far more profound. A discipline with social justice, civil liberties and human rights at its heart, would see these injustices for what they are, the creation of misery. It would identify, the increasing disproportionality of wealth in the UK and elsewhere and would see food banks, period poverty and homelessness as clearly criminal in intent and symptomatic of an unjust society.

Unless we can move past these law and order narratives and seek a criminology that is focused on making the world a better place, Foucault’s (1977) criticism must stand.

References

Bosworth, May and Hoyle, Carolyn, (2010), ‘What is Criminology? An Introduction’ in Mary Bosworth and Carolyn Hoyle, (2011), (eds), What is Criminology?, (Oxford: Oxford University Press): 1-12

Carlen, Pat, (2011), ‘Against Evangelism in Academic Criminology: For Criminology as a Scientific Art’ in Mary Bosworth and Carolyn Hoyle, (eds), What is Criminology?, (Oxford: Oxford University Press): 95-110

Cohen, Stanley, (1988), Against Criminology, (Oxford: Transaction Books)

Daly, Kathleen, (2011), ‘Shake It Up Baby: Practising Rock ‘n’ Roll Criminology’ in Mary Bosworth and Carolyn Hoyle, (eds), What is Criminology?, (Oxford: Oxford University Press): 111-24

Foucault, Michel, (1977), Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, tr. from the French by Alan Sheridan, (London: Penguin Books)

Wilson, Jeffrey R., (2015), ‘The Word Criminology: A Philology and a Definition,’ Criminology, Criminal Justice Law, & Society, 16, 3: 61-82

Why Criminology terrifies me

Cards on the table; I love my discipline with a passion, but I also fear it. As with other social sciences, criminology has a rather dark past. As Wetzell (2000) makes clear in his book Inventing the Criminal: A History of German Criminology 1880-1945 the discipline has (perhaps inadvertently) provided the foundations for brutality and violence. In particular, the work of Cesare Lombroso was utilised by the Nazi regime because of his attempts to differentiate between the criminal and the non-criminal. Of course, Lombroso was not responsible (he died in 1909) and could not reasonably be expected to envisage the way in which his work would be used. Nevertheless, when taken in tandem with many of the criticisms thrown at Lombroso’s work over the past century or so, this experience sounds a cautionary note for all those who want to classify along the lines of good/evil. Of course, Criminology is inherently interested in criminals which makes this rather problematic on many grounds. Although, one of the earliest ideas students of Criminology are introduced to, is that crime is a social construction, which varies across time and place, this can often be forgotten in the excitement of empirical research.

My biggest fear as an academic involved in teaching has been graphically shown by events in the USA. The separation of children from their parents by border guards is heart-breaking to observe and read about. Furthermore, it reverberates uncomfortably with the historical narratives from the Nazi Holocaust. Some years ago, I visited Amsterdam’s Verzetsmuseum (The Resistance Museum), much of which has stayed with me. In particular, an observer had written of a child whose wheeled toy had upturned on the cobbled stones, an everyday occurrence for parents of young children. What was different and abhorrent in this case was a Nazi soldier shot that child dead. Of course, this is but one event, in Europe’s bloodbath from 1939-1945, but it, like many other accounts have stayed with me. Throughout my studies I have questioned what kind of person could do these things? Furthermore, this is what keeps me awake at night when it comes to teaching “apprentice” criminologists.

This fear can perhaps best be illustrated by a BBC video released this week. Entitled ‘We’re not bad guys’ this video shows American teenagers undertaking work experience with border control. The participants are articulate and enthusiastic; keen to get involved in the everyday practice of protecting what they see as theirs. It is clear that they see value in the work; not only in terms of monetary and individual success, but with a desire to provide a service to their government and fellow citizens. However, where is the individual thought? Which one of them is asking; “is this the right thing to do”? Furthermore; “is there another way of resolving these issues”? After all, many within the Hitler Youth could say the same.

For this reason alone, social justice, human rights and empathy are essential for any criminologist whether academic or practice based. Without considering these three values, all of us run the risk of doing harm. Criminology must be critical, it should never accept the status quo and should always question everything. We must bear in mind Lee’s insistence that ‘You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view. Until you climb inside of his skin and walk around in it’ (1960/2006: 36). Until we place ourselves in the shoes of those separated from their families, the Grenfell survivors , the Windrush generation and everyone else suffering untold distress we cannot even begin to understand Criminology.

Furthermore, criminologists can do no worse than to revist their childhood and Kipling’s Just So Stories:

I keep six honest serving-men

(They taught me all I knew);

Their names are What and Why and When

And How and Where and Who (1912: 83)

Bibliography

Browning, Christopher, (1992), Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland, (London: Penguin Books)

Kipling, Rudyard, (1912), Just So Stories, (New York: Doubleday Page and Company)

Lee, Harper, (1960/2006), To Kill a Mockingbird, (London: Arrow Books)

Lombroso, Cesare, (1911a), Crime, Its Causes and Remedies, tr. from the Italian by Henry P. Horton, (Boston: Little Brown and Co.)

-, (1911b), Criminal Man: According to the Classification of Cesare Lombroso, Briefly Summarised by His Daughter Gina Lombroso Ferrero, (London: G. P. Putnam’s Sons)

-, (1876/1878/1884/1889/1896-7/ 2006), Criminal Man, tr. from the Italian by Mary Gibson and Nicole Hahn Rafter, (London: Duke University Press)

Solway, Richard A., (1982), ‘Counting the Degenerates: The Statistics of Race Deterioration in Edwardian England,’ Journal of Contemporary History, 17, 1: 137-64

Wetzell, Richard F., (2000), Inventing the Criminal: A History of German Criminology 1880-1945, (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press)

(In)Human Rights in the “Compliant Environment”

In the aftermath of the Windrush generation debacle being brought into the light, Amber Rudd resigned, and a new Home Secretary was appointed. This was hailed by the government as a turning point, an opportunity to draw a line in the sand. Certainly, within hours of his appointment, Sajid Javid announced that he ‘would do right by the Windrush generation’. Furthermore, he insisted that he did not ‘like the phrase hostile’, adding that ‘the terminology is incorrect’ and that the term itself, was ‘unhelpful’. In its place, Javid offered a new term, that of; ‘a compliant environment’. At first glance, the language appears neutral and far less threatening, however, you do not need to dig too deep to read the threat contained within.

According to the Oxford Dictionary (2018) the definition of compliant indicates a disposition ‘to agree with others or obey rules, especially to an excessive degree; acquiescent’. Compliance implies obeying orders, keeping your mouth shut and tolerating whatever follows. It offers, no space for discussion, debate or dissent and is far more reflective of the military environment, than civilian life. Furthermore, how does a narrative of compliance fit in with a twenty-first century (supposedly) democratic society?

The Windrush shambles demonstrates quite clearly a blatant disregard for British citizens and implicit, if not, downright aggression. Government ministers, civil servants, immigration officers, NHS workers, as well as those in education and other organisations/industries, all complying with rules and regulations, together with pressures to exceed targets, meant that any semblance of humanity is left behind. The strategy of creating a hostile environment could only ever result in misery for those subjected to the State’s machinations. Whilst, there may be concerns around people living in the country without the official right to stay, these people are fully aware of their uncertain status and are thus unlikely to be highly visible. As we’ve seen many times within the CJS, where there are targets that “must” be met, individuals and agencies will tend to go for the low-hanging fruit. In the case of immigration, this made the Windrush generation incredibly vulnerable; whether they wanted to travel to their country of origin to visit ill or dying relatives, change employment or if they needed to call on the services of the NHS. Although attention has now been drawn to the plight of many of the Windrush generation facing varying levels of discrimination, we can never really know for sure how many individuals and families have been impacted. The only narratives we will hear are those who are able to make their voices heard either independently or through the support of MPs (such as David Lammy) and the media. Hopefully, these voices will continue to be raised and new ones added, in order that all may receive justice; rather than an off-the-cuff apology.

However, what of Javid’s new ‘compliant environment’? I would argue that even in this new, supposedly less aggressive environment, individuals such as Sonia Williams, Glenda Caesar and Michael Braithwaite would still be faced with the same impossible situation. By speaking out, these British women and man, as well as countless others, demonstrate anything but compliance and that can only be a positive for a humane and empathetic society.