Home » Articles posted by Paula Bowles (Page 4)

Author Archives: Paula Bowles

Happy birthday and reflection on the (painful) art of writing

In November 2016, I had an idea that the Criminology team should create and maintain a blog. To that end I set up this account, put out a welcome message and then life (and Christmas, 2016) got in the way…. To cut a long story short, @manosdaskalou, @5teveh and I decided we’d give it a go, and on the 3 March 2017, @manosdaskalou broke our duck with the first post. This, of course, means we are celebrating the blog’s 4th birthday and it seems timely to reflect both on the blog and the (painful) art of writing.

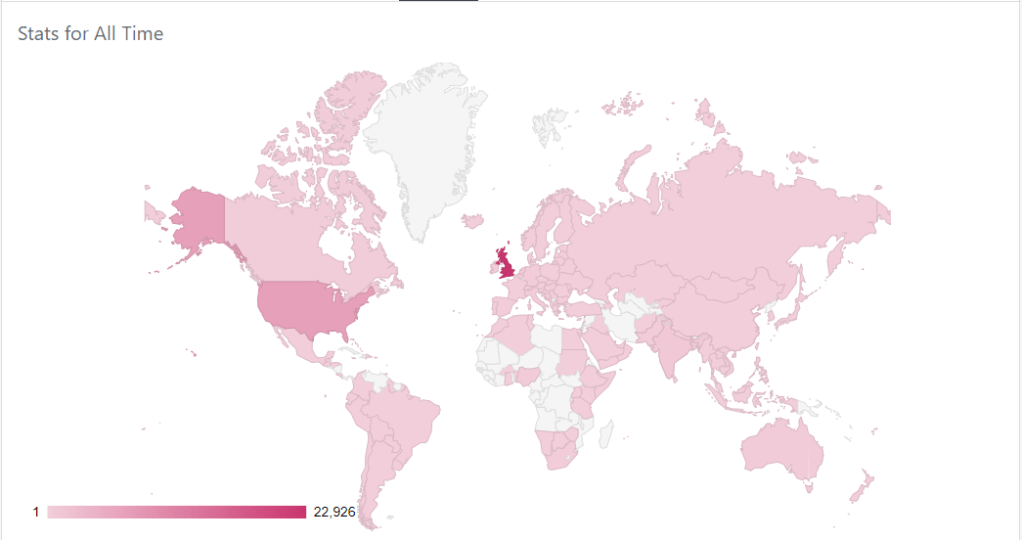

Since that early foray the blog has published almost 500 times and has been read by almost 23,000 people from across the globe. As you can see from the map below, we still have a few areas of the globe to reach, so if you have contacts, be sure to let them know about us 🙂

To date, our most read individual entry comes from a current student @zeechee, followed closely behind by one of @manosdaskalou‘s contributions and then one from @treventoursu. But of course, the most popular page of all is the front page where the most current entries are. That’s not to say that some entries don’t crop up again and again, for instance @manosdaskalou‘s most popular entry went live in May 2017, @zeechee‘s in January 2020 and @treventoursu‘s in February 2020. Sometimes these things take time to find their audience, but it shows you can’t hide excellent writing and content finds a way through.

Over the past 4 years we have had contributions from a wide range of people, some have contributed just one or two, others more frequently and the three founding members (once started) have never stopped blogging. During this time, bloggers have covered an enormous range of different topics, some with more frequency than others. Of course, this year much of the content, whether intended or not, has had connections to the ongoing global pandemic. The blog for both writers and readers has offered some distraction, even if only 5 minutes escape whilst waiting for the kettle to boil, from the devastation wrought by Covid-19.

All of the above gives us much to celebrate, not least our stamina and perseverance, but says nothing about the art of writing which I’d like to reflect on now. By the time it’s live on the blog, the process is forgotten, until the next entry becomes due. For some people writing comes easily, for me, it doesn’t. I find all kinds of writing painful and often like pulling teeth. I know what I want to say, I have a reasonable vocabulary, knowledge of my discipline and a keen eye on current affairs. All of this is true until I start the writing process….

Some of my reluctance relates to my individual personality, some to my social class and some to my gender. It is probably the latter two which create the highest barriers and I find myself in a spiral or internalised argument around who would want to read this, why should they, everyone knows this and on and on ad nauseum until I either write the sodding thing or very rarely, give up in disgust at my own ineptitude. I know this is irrational and I know that I have written many thousands of words in my lifetime, most largely forgotten in the fog of time, but still, every time the barriers shoot up. What makes it worse is that I can generally fulfil what ever writing brief I am confronted with, but only after a gargantuan battle of wills with myself.

Despite this a couple of things have helped considerably. The first is a talk originally give by Virginia Woolf in 1931. In this very short piece, entitled ‘Professions for Women’, Woolf details similar struggles, much more eruditely than I have, in relation to writing as a women.

The obstacles against her are still immensely powerful—and yet they are very difficult to define. Outwardly, what is simpler than to write books? Outwardly, what obstacles are there for a woman rather than for a man? Inwardly, I think, the case is very different; she has still many ghosts to fight, many prejudices to overcome. Indeed it will be a long time still, I think, before a woman can sit down to write a book without finding a phantom to be slain, a rock to be dashed against.

Woolf, 1931

She also names the internal conflict the ‘Angel in the House’. For Woolf, this creature has to be murdered in order for the female writer to make progress. For someone, like me committed to non-violence/pacifism, killing, even of an imaginary creature, is challenging, so instead I get in a few nudges, make my ‘angel’ agree to be quiet, even if only for a short time. As Woolf alludes, some days this works well, other times not so much, acknowledging that even when dead, the angel continues to undermine. Nevertheless this short essay helped me to understand that my so-called foibles were actually shared by other women and were formed during our socialisation. Because of this, I have regularly recommended to female students that they have a read and see if it helps them too.

The other thing that has really helped is the blog. The commitment to write regularly, to a deadline, has helped considerably. Although I know that I’m part of a team equally committed to the success of the blog, makes a difference. It ensures accountability. Of course, I could call on anyone of my colleagues to cover my slot, but I would be doing that knowing that I am adding to another person’s workload. Alternatively, I could opt not to write and leave a gapping hole on the blog that day/week, but again that would be letting down everyone on the blogging team, we all have a part to play. So sometimes reluctantly, other times with anger, still more times with passion, the words eventually come. I cannot speak for my fellow bloggers but I can say with some certainty blogging has done wonders for me in terms of accountability, not to mention the pleasure of working with a group of interesting and exciting writers on a regular basis.

Why not join us?

The Case of Mr Frederick Park and Mr Ernest Boulton

As a twenty-first century cis woman, I cannot directly identify with the people detailed below. However, I feel it important to mark LGBT+ History Month, recognising that so much history has been lost. This is detrimental to society’s understanding and hides the contribution that so many individuals have made to British and indeed, world history. What follows was the basis of a lecture I first delivered in the module CRI1006 True Crimes and Other Fictions but its roots are little longer

Some years ago I bought a very dear friend tickets for us to go and see a play in London (after almost a year of lockdowns, it seems very strange to write about the theatre).. I’d read a review of the play in The Guardian and both the production and the setting sounded very interesting. As a fan of Oscar Wilde’s writing, particularly The Ballad of Reading Gaol and De Profundis (both particularly suited to criminological tastes) and a long held fascination with Polari, the play sounded appealing. Nothing particularly unusual on the surface, but the experience, the play and the actors we watched that evening, were extraordinary. The play is entitled Fanny and Stella: The SHOCKING True Story and the theatre, Above the Stag in Vauxhall, London. Self-described as The UK’s LGBTQIA+ theatre, Above the Stag is often described as an intimate setting. Little did we know how intimate the setting would be. It’s a beautiful, tiny space, where the actors are close enough to just reach out and touch. All of the action (and the singing) happen right before your eyes. Believe me, with songs like Sodomy on the Strand and Where Has My Fanny Gone there is plenty to enjoy. If you ever get the opportunity to go to this theatre, for this play, or any other, grab the opportunity.

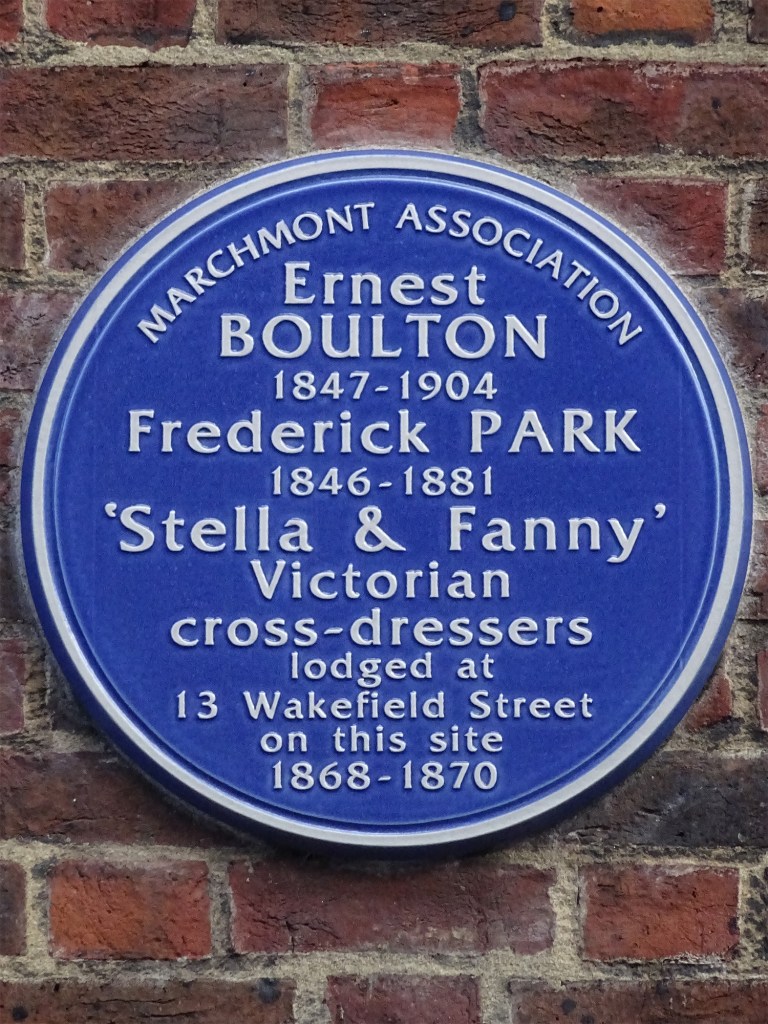

So who were Fanny and Stella? Christened Frederick Park (1848-1881) and Ernest Boulton (1848-1901), their early lives are largely undocumented beyond the very basics. Park’s father was a judge, Boulton, the son of a stockbroker. As perhaps was usual for the time, both sons followed their respective fathers into similar trades, Park training as an articled clerk, Boulton, working as a trainee bank clerk. In addition, both were employed to act within music halls and theatres. So far nothing extraordinary….

But on the 29 April 1870 as Fanny and Stella left the Strand Theatre they were accosted by undercover police officers;

‘“I’m a police officer from Bow Street […] and I have every reason to believe that you are men in female attire and you will have to come to Bow Street with me now”’

(no reference, cited in McKenna, 2013: 7)

Upon arrest, both Fanny and Stella told the police officers that they were men and at the police station they provided their full names and addresses. They were then stripped naked, making it obvious to the onlooking officers that both Fanny and Stella were (physically typical) males. By now, the police had all the evidence they needed to support the claims made at the point of arrest. However, they were not satisfied and proceeded to submit the men to a physically violent examination designed to identify if the men had engaged in anal sex. This was in order to charge both Fanny and Stella with the offence of buggery (also known as sodomy). The charges when they came, were as follows:

‘they did with each and one another feloniously commit the abominable crime of buggery’

‘they did unlawfully conspire together , and with divers other persons, feloniously, to commit the said crimes’

‘they did unlawfully conspire together , and with divers other persons, to induce and incite other persons, feloniously, to commit the said crimes’

‘they being men, did unlawfully conspire together, and with divers others, to disguise themselves as women and to frequent places of public resort, so disguised, and to thereby openly and scandalously outrage public decency and corrupt public morals’

Trial transcript cited in McKenna (2013: 35)

It is worth noting that until 1861 the penalty for being found guilty of buggery was death. After 1861 the penalty changed to penal servitude with hard labour for life.

You’ll be delighted to know, I am not going to give any spoilers, you need to read the book or even better, see the play. But I think it is important to consider the many complex facets of telling stories from the past, including public/private lives, the ethics of writing about the dead, the importance of doing justice to the narrative, whilst also shining a light on to hidden communities, social histories and “ordinary” people. Fanny and Stella’s lives were firmly set in the 19th century, a time when photography was a very expensive and stylised art, when social media was not even a twinkle in the eye. Thus their lives, like so many others throughout history, were primarily expected to be private, notwithstanding their theatrical performances. Furthermore, sexual activity, even today, is generally a private matter and there (thankfully) seems to be no evidence of a Victorian equivalent of the “dick pic”! Sexual activity, sexual thoughts, sexuality and so on are generally private and even when shared, kept between a select group of people.

This means that authors working on historical sexual cases, such as that of Fanny and Stella, are left with very partial evidence. Furthermore, the evidence which exists is institutionally acquired, that is we only know their story through the ignominy of their criminal justice records. We know nothing of their private thoughts, we have no idea of their sexual preferences or fantasies. Certainly, the term ‘homosexual’ did not emerge until the late 1860s in Germany, so it is unlikely they would have used that language to describe themselves. Likewise, the terms transvestite, transsexual and transgender did not appear until 1910s, 1940s and 1960s respectively so Fanny and Stella could not use any of these as descriptors. Despite the blue plaque above, we have no evidence to suggest that they ever described themselves as ‘cross-dressers’ In short, we have no idea how either Fanny or Stella perceived of themselves or how they constructed their individual life stories. Instead, authors such as Neil McKenna, close the gaps in order to create a seamless narrative.

McKenna calls upon an excellent range of different archival material for his book (upon which the play is based). These include:

- National Archives in Kew

- British Library/British Newspaper Library, London

- Metropolitan Police Service Archive, London

- Wellcome Institute, London

- Parliamentary Archives, London

- Libraries of the Royal Colleges of Surgeons, London and Edinburgh

- National Archives of Scotland

Nevertheless, these archives do not contain the level of personal detail, required to tell a fascinating story. Instead the author draws upon his own knowledge and understanding to bring these characters to life. Of course, no author writes in a vacuum and we all have a standpoint which impacts on the way in which we understand the world. So whilst, we know the institutional version of some part of Fanny and Stella’s life, we can never know their inner most thoughts or how they thought of themselves and each other. Any decision to include content which is not supported by evidence is fraught with difficulty and runs the risk of exaggeration or misinterpretation. A constant reminder that the two at the centre of the case are dead and justice needs to be done to a narrative where there is no right of response.

It is clear that both the book and the play contain elements that we cannot be certain are reflective of Fanny and Stella’s lives or the world they moved in. The alternative is to allow their story to be left unknown or only told through police and court records. Both would be a huge shame. As long as we remember that their story is one of fragile human beings, with many strengths and frailties, narratives such as this allow us a brief glimpse into a hidden community and two, not so ordinary people. But we also need to bear in mind that in this case, as with Oscar Wilde, the focus is on the flamboyantly illicit and tells us little about the lived experience of some many others whose voices and experiences are lost in time..

References

McKenna, Neil, (2013), Fanny and Stella: The Young Men Who Shocked Victorian England, (London: Faber and Faber Ltd.) Norton, Rictor, (2005), ‘Recovering Gay History from the Old Bailey,’ The London Journal, 30, 1: 39-54 Old Bailey Online, (2003-2018), ‘The Proceedings of the Old Bailey,’ The Old Baily Online, [online]. Available from: https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/ [Last accessed 25 February 2021]

How should we honour “Our sheroes and heroes”?*

The British, so it seems, love a statue. Over the last few months we’ve seen Edward Colston’s toppled, Winston Churchill’s protected and Robert Baden-Powell’s moved to a place of safety. Much of the narrative around these particular statues (and others) has recently been contextualised in relation to the Black Lives Matter movement, as though nobody had ever criticised the subjects before. Colston, one time resident of Bristol and slave-trader was deemed worthy of commemoration some 174 years after his death and 62 years after the abolition of slavery. Likewise, one-time military man, accused of war crimes, homophobe and support for Nazism, Baden-Powell suddenly needed to be memorialised in 2008, almost 70 years after the second world world (and his death) and over 40 years since the passing of the Sexual Offences Act 1967. For both of these men profound problems were clear before the statues went up. Churchill, seen as a “hero” by many for his leadership in World War II has a very unsavoury history which is not difficult to locate in his own writings. His rehabilitation also ignores that his status for many of his contemporaries was as a warmonger. His passion for eugenics and his role in decisions to bomb Dresden, Hiroshima and Nagasaki can be wilfully swept under the carpet. Hero-worship is a dangerous game, it is also anti-intellectual. Churchill, like all of us, was a complex human, thus his legacy needs to be explored deeply and contextualised and only then can we decide what his place in his history should be. His statues and soundbites from speeches on repeat, do not allow for this.

Perhaps the most interesting part of this debate is to witness the inflamed defence of individuals who have a clearly documented history as slave owners, or as enthusiastic proclaimers of eugenic ideology, racism, homophobia and so on. As long as they have been ascribed “hero” status, we can ignore the rest of the seedy detail. We are told we need these statues, these heroic men, to remind us of our history….strangely Germany is able to reflect on its history, without statues of Hitler.

It seems as a nation we far prefer these individuals, responsible for so much misery, harm and violence in their lifetimes, than to present Black Britons and British Asians on a plinth. When we are reliant on South African President, Nelson Mandela to take up two of those London plinths, it is evident we have a serious racial imbalance in those “we” choose to commemorate.

Furthermore, the British appear to love an argument about statues, for instance, the criticism levelled at the artist Maggi Hambling’s statue to “Mother of Feminism” Mary Wollstencraft and Martin Jenning’s artistic tribute to Nurse Mary Seacole. For Wollstencroft, much of the furore has been directed at the artist, rather than the subject. There appears to be no irony in women attacking other women, in this case, Hambling, all in the name of supposed defence of The feminism. In the case of Mary Seacole, racially infused arguments from The Nightingale Society have suggested that this statue should not be in sight of that of Florence Nightingale. It seems that even when all important parties are long dead, it is deemed appropriate to use barely disguised racism to protect the stone image of your heroine. Important to remember that patriarchy has no gender. It is evident that criticism revolves around women’s representation in statuary, as well as women’s involvement in sculpture. When statues of men are said to outnumber those of women by around 16 to 1 (and that’s only when Queen Victoria is counted) it is evident we have a serious gender imbalance in those “we” choose to commemorate.

If there’s one thing the British love more than statues, it’s war commemorations. Think of the Cenotaph, standing proud in Whitehall, a memorial to ‘The Glorious Dead’ of firstly, World War I and latterly, British and Commonwealth military personnel have died in all conflicts.

Close by in Park Lane, we even have the imagination to create a memorial to Animals in War. We love to worship at these altars to untold misery and suffering, as if we could learn something important from them. Unfortunately, the most important message of “Never Again” is lost as we continue to thrust our military personnel and their deadly arsenal all over the world.

There is a strong argument for commemorating the war dead of all nations in the two World Wars. All sides, both central powers/axis and allies were comprised in the main of conscripted personnel. These were men and women that did not join the armed forces voluntarily, but were compelled by legislation to take up arms. With little time to consider or prepare, these people, all over the world, were thrust into life-threatening situations, with little or no choice. The Cenotaph and other war memorials mark this sacrifice and to some degree, acknowledge the experiences of those who served in a uniform that they did not consent to, without the compulsion of legislation. Unfortunately, civilians don’t feature so heavily in memorialisation, yet we know they experienced life-changing events which have repercussions even today. From children who were evacuated, to families who experienced fathers and husbands with short fuses, to those whose fear of hunger has never really left them, those experiences leave a mark.

To me, as a nation it appears that we don’t want to engage seriously with our history, preferring instead a white-washed, heteronormative, male-dominated, war-infused, saccharine sweet, version of events. But British people, both historically and contemporaneously, are a diverse and disparate group, good, bad and indifferent, so surely our statues should reflect this?

I recognise the violence which runs throughout British history, I learnt it, not through statues, but through books and oral testimony, through documentary and discussion. I also recognise that I have only begun to explore a history that silences so very many, making any historical narrative, partial, poignant and heavy with the missing voices. I recognise the heavy burden left by slavery, discrimination, war and other myriad violences, understanding the desire to commemorate and celebrate and tear down and replace.

What we need is a statue that recognises all of us, in all shapes and sizes, warts and all? We are living in a global pandemic, the death toll is currently standing at over 2.5 million. In the UK alone, the death toll stands at close to 100,000. Why not have a memorial with all those names; men, women, children, Black, white, Asian, mixed heritage, Muslim, Catholic, Buddhist, Christian, atheists, gay, straight, trans, lesbian, young, old and all those in between. People that have been coerced, through financial impetus, caring responsibility, career or vocation into dangerous spaces, who have not chosen to sacrifice their lives on the altar of bad decisions taken by governments and institutions (reminiscent of the world wars). Such a commemoration would be a way to recognise the profound impact on all of our lives, as drastic as any world war. It will recognise that you don’t have to wear a uniform or conform to a particular ideal to be of value to Britain and every person counts.

* Title borrowed from ‘Our sheroes and heroes’ (Maya Angelou ; interviewed by Susan Anderson in 1976)

2020: A Year on “Plague Island”

Last year in this blog, I argued that 2019 had been a year of violence. My colleague, @5teveh provided a gentle riposte, noting that whilst things had not been that good, they were perhaps not as bad as I had indicated. Looking back at both entries it is clear that my thoughts were well-evidenced, but it is @5teveh‘s rebuttal that has proved most prescient in respect of what was to come….

The year started off on a positive, personally and professionally, when both @manosdaskalou and I were nominated for Changemaker Awards. Although beaten by some very tough competition, shortly before leaving campus we were both awarded High Sheriff Awards, alongside our prison colleagues, for our module CRI3006 Beyond Justice. As colleagues and students will know, this module is taught entirely in prison to year 3 criminology students and their incarcerated peers. Unfortunately, the awards took place in the last week on campus, but we are hopeful that we can continue to work together in the near future.

Understandably much of our attention this year has been on Covid-19 and the changes it has wrought on individuals, communities, society and globally. Throughout this year, the Thoughts from the Criminology Team have documented the pandemic in a variety of different ways. From my very early thoughts, written in the panic of abandoning campus for the experience of lockdown to entries from @helentrinder @treventoursu @jesjames50 @cherylgardner2015 @5teveh @manosdaskalou @anfieldbhoy @samc0812 @drkukustr8talk @zeechee @saffrongarside @svr2727 @haleysread The blog has explored Covid-19 from a variety of different angles reflecting on the unprecedented experience of living through a pandemic. It is interesting to see how the situation and our understanding and responses have adapted over the past 9 months.

Alongside the serious materials, it was obvious very early on that we also needed to ensure some lightness for the team and our readers. With this in mind, early in the first lock down, we created the #CriminologyBookClub. We’re currently on our 8th novel and we’ve been highly critical of some of the texts ;), as well as fallen in love with others. However, I know I speak for my fellow members when I say this has offered some real respite for what’s going on around us.

Another early initiative was to invite all our bloggers to contribute an entry entitled #MyFavouriteThings. We ended up with over twenty entries (which you’ll find via the link) from the criminology team, students, as well as a our regular and occasional contributors. Surprisingly we learnt a lot about each other and about ourselves. The process of something as basic as writing down your favourite things, proved to be highly cathartic.

Whilst supporting each other in our learning community, we also didn’t forget our friends and colleagues in prison. Although, the focus has rightly been on the NHS and carers, the pandemic has hit the prison communities very hard. Technology can solve some of the issues of loneliness, but to be locked in a small room, far away from family and friends creates additional problems. For the men and the staff, the last 9 months has brought challenges never seen before. Although, we could not teach the module, we did our best, along with colleagues in Geography and the Vice Chancellor @npetfo, to provide quizzes and competitions to help pass the hours.

In June, the world was shocked by the killing of George Floyd in the USA. For many of us, this death was one in a long line of horrific killings of Black men and women, whereby society generally turned a blind eye. However, in the middle of a pandemic, the killing of George Floyd meant that people could not turn away from what was playing on every screen and every platform. This lead to a resurgence of interest in Black Lives Matter and an outpouring of statements by individuals, organisations, institutions and the State.

For a week in June, the Thoughts from the Criminology Team muted all their social media to make space for the #AmplifyMelanatedVoices initiative from Alishia McCullough and Jessica Wilson This was a tiny gesture in the grand scheme of things but refocused the team’s attention on making sure there is a space for anyone who wants to contribute.

Whether this new found interest in Black Lives Matters and discussions around diversity, racism, decolonisation and disproportionality continue, remains to be seen. Hopefully, the killing of George Floyd, alongside the profound evidence of privilege and need made evident by the pandemic, has provided a catalyst for change. One thing is clear, everyone knows now, we can no longer hide, there are no more excuses and we all can and must do better.

This year some old faces left for pastures new and we welcomed some new colleagues to the Criminology Team. If you haven’t already, you can read about our new (or, in some cases, not so new) team members’ – @jesjames50 @haleysread and @amycortvriend – academic journeys to becoming Lecturers in Criminology.

Finally, looking back over the last 12 months, certain themes catch my eye. Some of these are obvious, the pandemic and Black Lives Matter have occupied a lot of our minds. The focus has often been on high profile individuals – Captain Tom Moore, Joe Wickes, Marcus Rashford – but has also shone on teams/organisations/institutions such as the NHS, carers, shop workers, delivery drivers, the scientists working on the vaccines, the list goes on. Everyone has played a part, even if that is just by staying at home and out of the way, leaving space for those with a frontline role to play. Upon reflection it is evident that the over-riding themes (and why @5teveh was right last year) are ones of kindness, of going the extra mile, of trying to listen to each other, of reaching out to each other, acknowledging unfairness and privileges, recognising the huge loss of life and the impact of illness and bereavement and trying to make things a little better for all. Hope has become the default setting for all of us, hope that the pandemic will be over, alongside hopes that we can build a better world with its passing. It has also become extremely clear that critical thinking is at a premium during a pandemic, with competing narratives, contradictory evidence and uncertainty, testing all of our ability to cope with change and respond with humility and humanity.

There is no doubt 2020 has been an unprecedented year and one that will stay with us for ever in the collective memory. Going into 2021 it’s important that we remember to consider the positives and keep trying to do better. Hopefully, in 2021 we will get to celebrate Criminology’s 21st Birthday together

Remember to stay safe, strong and well and look out for yourself and others.

#CriminologyBookClub: The Perplexing Theft of the Jewel in the Crown

As you know from our last #CriminologyBookClub entry a small group of us decided the best way to thrive in lockdown was to seek solace in reading and talking about books. Building on on what has quickly become standard practice, we’ve decided to continue with all seven bloggers contributing! Our fourth book was chosen by all of us (unanimously) after we fell in love with the first instalment. Without more ado, let’s see why we all adore Inspector Chopra (retired) et al.:

Another great edition to the Baby Ganesh agency series. After thoroughly enjoying the first book, I was slightly sceptical that book 2 would bring me the same level of excitement as the former. I was pleasantly surprised! The Perplexing Theft of the Jewel in the Crown, will take you on a picturesque journey across Mumbai. The story definitely pumps up the pace giving the reader more mystery and excitement. We now get more of an insight into characters such as inspector Chopra (retired) and his devoted wife Poppy. We also get to meet some new characters such as the loveable young boy Irfan, and of course the star of the show Ganesh, Chopra’s mysterious elephant. This novel has mystery within mystery, humour, suspense and some history, which is a great combination for anyone who wants to have an enjoyable read.

@svr2727

In the second instalment of detective Chopra’s detective (retired) adventures he is investigating the disappearance of the infamous Koh-i-noor diamond. The mythical gem disappears from a well-guarded place putting a strain on Anglo-Indian relations. In the midst of an international incident, the retired inspector is trying to make sense of the case with his usual crew and some new additions. In this instalment of the genre, the cultural clash becomes more obvious, with the main character trying to make sense of the colonial past and his feelings about the imprint it left behind. The sidekick elephant remains youthful, impulsive and at times petulant advancing him from a human child to a moody teenager. The case comes with some twists and turns, but the most interesting part is the way the main characters develop, especially in the face of some interesting sub-plots

@manosdaskalou

I am usually, very critical, of everything I read, even more so of books I love. However, with Inspector Chopra et al., I am completely missing my critical faculties. This book, like the first, is warm, colourful and welcoming. It has moments of delightful humour (unicycles and giant birthday cake), pathos (burns and a comforting trunk) to high drama (a missing child and pachyderm). Throughout, I didn’t want to read too much at any sitting, but that was only because I didn’t want to say goodbye to Vaseem Khan’s wonderful characters, even if only for a short while…

@paulaabowles

It was a pleasure to read the second book of the Inspector Chopra series. Yes, sometimes the characters go through some difficult times, the extreme inequalities between the rich and poor are made clear and Britain’s infamous colonial past (and present) plays a significant part of the plot, yet the book remains a heart-warming and up-beat read. The current character developments and introduction of new character Irfan is wonderfully done. Cannot wait to read the next book in the series!

@haleysread

One of the reasons for critiquing a book is to provide a balanced view for would be readers. An almost impossible task in the case of Vaseem Khan’s second Baby Ganesh Agency Investigation. Lost in a colourful world, and swept along with the intrigue of the plot and multiple sub plots involving both delightful and dark characters, the will to find a crumb of negativity is quickly broken. You know this is not real and, yet it could be, you know that some of the things that are portrayed are awful, but they just add to the narrative and you know and really hope that when the baby elephant Ganesha is in trouble, it will all work out fine, as it should. Knowing these things, rather than detracting from the need to quickly get to the end, just add to the need to turn page after page. Willpower is needed to avoid finishing the book in one hit. Rarely can I say that once again I finished a book and sat back with a feeling of inner warmth and a smile on my face. If there is anything negative to say about the book, well it was all over far too quickly.

@5teveh

The second Inspector Chopra book is even more thrilling than the first! As I read it I felt as though I genuinely knew the characters and I found myself worrying about them and hoping things would resolve for them. The book deals with some serious themes alongside some laugh out loud funny moments and I couldn’t put it down. Can’t wait to read the third instalment!

@saffrongarside

I have always found that the rule for sequels in film is: they are never a good as the original/first. Now, there are exceptions to the rule, however these for me are few and far between. However, when it comes to literature I have found that the sequels are as good if not better than the original- this is the rule. And my favourite writers are ones who have created a literature series (or multiple): with each book getting better and better. The Perplexing Theft of the Jewel in the Crown (Chopra 2.0) by Vaseem Khan has maintained my rule for literature and sequels! Hurray! After the explosive first instalment where we are introduced to Inspector Chopra, Poppy and Baby Ganesha, the pressure was well and truly on for the second book to deliver. And By Joe! Deliver it did! Fast paced, with multiple side-stories (which in all fairness are more important that the theft of the crown), reinforce all the emotion you felt for the characters in the first book and makes you open your heart to little Irfan! Excellent read, beautiful characters, humorous plots! Roll on book number 3!

@jesjames50

Time to hear from our students

As part of their commitment to provide an inclusive space to explore a diversity of subjects, from a diverse range of standpoints, the Thoughts from the Criminology team have decided to introduce a new initiative.

From tomorrow (Sunday 21 June) all weekend posts will come from our students. We know that all of our students have plenty to say, they are smart, articulate and have both academic and experiential knowledge on which to draw. We know our readers will be as impressed as we are, by their passion and their criminological imagination.

Over to you, Criminology Students!

The pandemic and me – Paula

Portrait de Dora Maar, Pablo Picasso, 1937

The last time I physically went to work was Thursday 19 March, over 12 weeks ago. Within days, I blogged about the panic and fear that risked overwhelming us all in the light of a pandemic. Some of that entry was based on observation and the media, other parts, my own feelings and emotions.

Prior to the pandemic, I had been the kind of person that felt the need to be at work, often for 10-12 hours a day This was partly to kid myself that there was a clear delineation between the personal and the professional (something, I’ve never managed to achieve since joining academia). Part of it was due to my previous career in retail; when there are customers there must be staff, so there is a necessity to presence. Part of it was tied up with notions of work ethic and fear of missing out, dropping out, losing connection. The regularity of the Monday to Friday (and sometimes, Saturdays for events) commute there and back, the same familiar route, the same familiar timetable, the same familiar faces. Even prosaic matters, like my wardrobe, is primarily designed for my professional life, however, #lockdown life requires something different than formal suit, dresses and court shoes. Similarly, make-up seems out of place, why paint your face or nails, without the rest of the professional apparatus, deemed so necessary to what Goffman (1969/1990) identified as The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life.

In his play Huis Clos (No Exit) Jean-Paul Sarte famously claimed that ‘Hell is—other people’ (1947/1989: 45). This is often interpreted as if the company of others is hellish, but that is a misreading. Sartre, like Mead (1934) before him recognised the role of the other, in our own understanding of ourselves. In essence, we can only ever see ourselves through the lens of others. In lockdown that lens dissipates or even disappears entirely, even with technology, which although we appreciate as an enabler of communication, I’ve yet to hear anyone say it is a complete replacement for human interaction.

Nevertheless, lockdown has forced us to look again and not only at our wardrobes. Once the panic and the novelty of not going to work, socialising and all the other activities, that are part and parcel of our lived experience passed, a new normality replaced this. Introspection is often missing in twenty-first century life, even among those of us that spend considerable amounts of time, professionally, if not personally, reflecting on what we’ve said, what we’ve done and how we can change, amend and ultimately improve as human beings. It’s also provided space to consider what we can’t wait to get back to, what we’re glad to have a break from and what we are looking for ways to avoid in the future.

For me, part of that introspection has focused on my need to be present at work. After all, in academia there is less pressure to be on campus, particularly on one which has been designed with the future in mind. There is no office, where I need to water plants, (most of) my academic books are here and I also have a work laptop, as well as my own pc. At home, I can have silence, or music while I work. If I am hungry or thirsty I can satisfy those needs. If I am overwhelmed, I can simply walk away for a little while, without explanation. If I am lonely, confused or need advice, I can pick up the phone, message, video call and everything else that technology can offer. My professional life can pretty much continue without too much interruption.

So what happens when things return to normal, should I throw myself back into the same patterns as before? I am hoping the answer is no, that I will do things differently, not least for my own wellbeing. Although I love the look and feel of the campus, I have always struggled with what, criminologists will understand as the panoptic gaze (Foucault, 1977). The sense that wherever you are, the threat of observation is ever present. The panoptic gaze does not differentiate between deviant or pro-social activity, it simply retains its disciplinary function designed to constrain and control For many, it is an open welcoming space, however, as a person who thrives on quietness, on privacy, on spending time away from human contact, it can have the opposite effect. Not all of the time, but at least some of it, I wouldn’t want to abandon campus life completely. The lockdown has shown me that it is possible to have the best of both worlds

References

Foucault, Michel, (1977), Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, tr. from the French by Alan Sheridan, (London: Penguin Books)

Goffman, Erving, (1959/1990), The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, (London: Penguin)

Mead, George Herbert. (1934). Mind, Self and Society: From the Standpoint of a Social Behaviorist. (Ed. Charles W. Morris). (Chicago: Chicago University Press)

Sartre, Jean-Paul, (1947/1989), No Exit and Three Other Plays, (New York: Vintage International)

The worldwide reaction to the murder of George Floyd has shocked me, the murder of George Floyd has not. Another of our students speaks out

A cracking entry from BA History & Media Production student Amelia. Plenty for criminology scholars to think about

“I Can’t Breathe…”

A very thoughtful reflection on George Floyd and #BlackLivesMatter from Criminology graduate @flowerviolet

“I can’t breathe”… “I can’t breathe”

Those haunting words were the last of George Floyd whom, after 8 minutes and 46 seconds of having a police officer kneel on his neck, lost his life.

The video of his death sparked outrage, and protests took place as part of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement in combating racism and racial injustice, and to get justice for George Floyd and his family. The Black Lives Matter movement started in 2013 by 3 radical black women; Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi (1).

The Black Lives Matter movement was founded in response acquittal of Trayvon Martin’s murderer, George Zimmerman, and focuses on the affirmation of the humanity of black people, and the constant struggle with everyday racism and racial injustice (2). Racism is still a huge problem, and has always been a problem globally.

“I can’t breathe….”

Great Britain’s history…

View original post 693 more words

#amplifymelanatedvoices 2020

Over the past week or so, the Thoughts From the Criminology Team has taken part in the #amplifymelanatedvoices initiative started by @blackandembodied and @jessicawilson.msrd over on Instagram. During that time we have re-shared entries from our regular bloggers @treventoursu and @drkukustr8talk as well as entries from our graduates @franbitalo, @wadzanain7, @sineqd, @sallekmusa, @tgomesx, @jazzie9, @chris13418861 and @ifedamilola. In addition, we have new entries from @treventoursu, @drkukustr8talk and @svr2727. Each of these entries has offered a different perspective and each has provided the starting point for further dialogue.

We recognise that taking part in the #amplifymelanatedvoices is a tiny gesture, and that everyone can and should do better in the fight against white supremacy, racist ideology and individual and institutional violences.

Although this particular initiative has come to an end, the Thoughts from the Criminology Team retains its ethos, which is ‘to provide an inclusive space to explore a diversity of subjects, from a diverse range of standpoints’. We hope all of our bloggers continue to write for us for many years, but there is plenty of room for new voices.