Home » Articles posted by Paula Bowles

Author Archives: Paula Bowles

Happy Birthday: The Blog in Pictures, Numbers and Words

Tuesday marked the 8th “official” birthday of our blog. I say official because although the site was created in November of 2016, the writing did not start in earnest until 3 March. Since that early foray into blogging, we’ve managed collectively to clock up quite a few vital statistics

Our 78 bloggers are made of the Criminology Team (both past and present), students and graduates, as well as a number of honorary criminologists. Some have written only one entry, perhaps reflecting on their dissertation, while others have and continue to contribute on a regular or ad hoc basis. It has to be said that 9 of our top 20 most read entries come from students/graduates, another two come from non-criminologists. Certainly graduate and student entries are always very popular. Our most read, continues to be the front page which contains the latest entries, but many of our entries have shown remarkable longevity. For instance, then student, now graduate, Natalie’s (@criminologysocietyuon) thoughts around the “true crime” documentary Betty Broderick remains our most read individual entry, clocking up views ever since the day it was published. This demonstrates the enormous appetite for “true crime” that many people have. Likewise, Dr Stephen O’Brien’s (@anfieldbhoy) reflections on the 30th anniversary of the Hillsborough Disaster continues to be well-read, particularly around the anniversary on 15 April. In the words of the poet, Ella Wheeler Wilcox: ‘No question is ever settled, until it is settled right’ and there is certainly a long way to go to obtain justice for the 97.

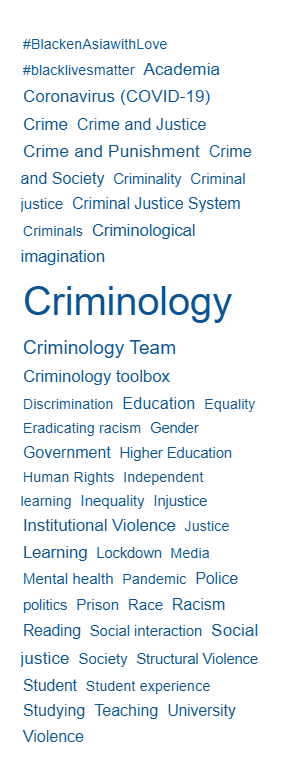

As can be seen from the word cloud, which appears on the front page of the blog and below, Criminology unsurprisingly occupies the attention of most of our bloggers and entries. However, it is also clear that social injustice, inequalities and various forms of violence appear regularly within our writing. There is also a strong focus on learning and teaching, as well as evidence of the lasting generational impact of the Covid-19 pandemic (our best year for readership to date).

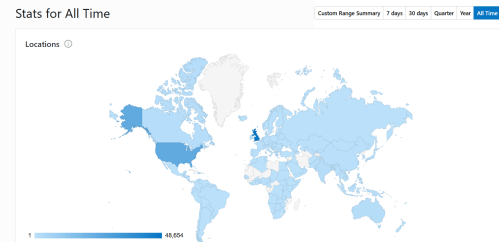

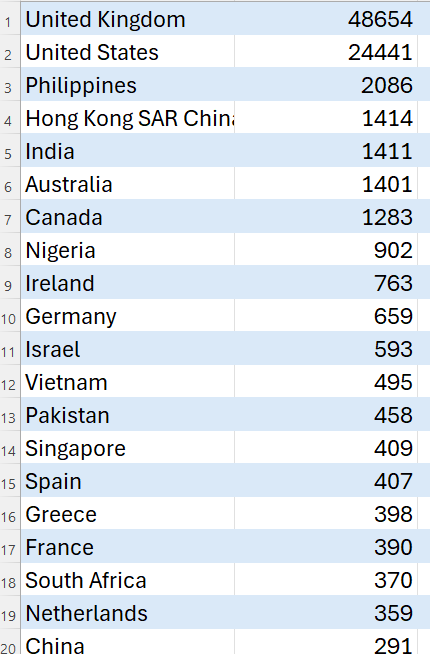

As you can see from the map the majority of our readers come from the UK and the USA, but we’ve also captured the criminological imagination of people from a diverse range of countries ranging from Albania to Zambia. Some of the countries can be explained through our bloggers’ diverse heritage, for instance, Greece, Nigeria, USA have obvious connections, others, we’ve no idea how our words have spread so far. Nevertheless, it is a very exciting to see the blog’s global reach.

As the saying goes, from small acorns to giant oaks, the germ of an idea has spread beyond any of our wildest dreams. The number of blog entries continues to grow on a weekly basis, it seems we never run out of criminological matters to write about. It has given all of us a space to ponder, to muse, to write through dark days and celebrations, and to continue to engage in Public Criminology. Similarly, the number of bloggers steadily rises, some are in their earliest foray into discovering Criminology, some have years of immersion in the discipline, but we are all learners. In the words of Nelson Mandela: ‘Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world’ so why would we ever want to stop learning?

When we started, we thought the blog would last for a year, maybe, either we’d run out of things to write about or we’d find other things to do with our time. Neither has happened and it seems there is still plenty of appetite from our bloggers and our readers. To both we raise a glass, without you, none of this would have been possible, so thank you! Now, let’s see how long we can keep this up!

Is it time to unleash your criminological imagination?

In this blog entry, I am going to introduce a seemingly disconnected set of ideas. I say seemingly, because at the end, all will hopefully make sense. I suspect the following also demonstrates the often chaotic and convoluted process of my thought processes.

I’ve written many times before about Criminology, at times questioning whether I have any claim to the title criminologist and more recently, what those with the title should talk about. These come on top of hundreds of hours of study, contemplation and reflection which provides the backdrop for why I keep questioning the discipline and my place within it. I know one of the biggest issues for me is social sciences, like Criminology and many others, love to categorise people in lots of different ways: class, race, gender, offender, survivor, victim and so on. But people, including me, don’t like to be put in boxes, we’re complex animals and as I always tell students, people are bloody awkward, including ourselves! There is also a far more challenging issue of being part of a discipline which has the potential to cause, rather than reduce or remove harm, another topic I’ve blogged on before.

It’s no secret that universities across the UK and further afield are facing many serious, seemingly intractable challenges. In the UK these range from financial pressures (both institutional and individual), austerity measures, the seemingly unstoppable rise of technology and the implicit (or explicit, depending on standpoint) message of Brexit, that the country is closed to outsiders. Each of the challenges mentioned above seem to me to be anti-education, rather than designed to expand and share knowledge, they close down essential dialogue. Many years ago, a student studying in the UK from mainland Europe on the Erasmus scheme, said to me that our facilities were wonderful, and they were amazed by the readily available access to IT, both far superior to what was available to them in their own country. Gratifying to hear, but what came next was far more profound, they said that all a serious student really need is books, a enthusiastic and knowledgeable teacher and a tree to sit under. Whilst the tree to sit under might not work in the UK with our unpredictable weather, the rest struck a chord.

The world seems in chaos and war-mongers everywhere are clamouring for violence. Recent events in Darfur, Palestine, Sudan, Ukraine, Venezuela and many other parts of the world, demonstrate the frailty, or even, fallacy of international law, something Drs @manosdaskalou, @paulsquaredd and @aysheaobrien1ca0bcf715 have all eloquently blogged about. But while these discussions are important and pertinent, they cannot address the immediate harm caused to individuals and populations facing these many, varied forms of violence. Furthermore, whilst it’s been over 80 years since Raphäel Lemkin first coined the term ‘genocide’, it seems world leaders are content to debate whether this situation or that situation fits the definition. But, surely these discussions should be secondary, a humanitarian response is far more urgent. After all, (one would hope) that the police would not standby watching as one person killed another, all whilst having a discussion around the definition of murder and whether it applied in this context.

The rise of technology, in particular Generative Artificial Intelligence, has been the focus of blogs from Drs @sallekmusa, @5teveh and myself, each with their own perspective and standpoint. Efforts to combat the harmful effects of Grok enabling the creation of non-consensual pornographic images demonstrate both new forms of Violence Against Women and Girls [VAWG] and the limitations of control and enforcement. Whilst countries are rushing to ban Grok and control the access of social media for children under 16, it is clear that Grok and X are just one form of GAI and social media, there is seemingly nothing to stop others taking their place. And as everyone is well aware, laws are broken on a daily basis (just look at the court backlog and the overflowing prisons) and with no apparent way of controlling children’s access to technology (something which is actively encouraged in schools, colleges and universities) these attempts seem doomed to fail. Maybe more regulation. more legislation isn’t the answer to this problem.

Above I have briefly discussed four seemingly intractable problems. In each arena, we have many thousands of people across the globe trying to solve the issues, but the problems still remain. Perhaps we should ask ourselves the following questions:

- Maybe we are asking the wrong people to come up with the answers?

- Maybe we are constraining discussions and closing down debate?

- Maybe by allowing the established and the powerful to control the narrative we just continue to recycle the same problems and the same hackneyed solutions?

What if there’s another way?

And here we come to the crux of this blog, in Criminology we are challenged to explore any problem from all perspectives, we are continually encouraged to imagine a different world, what ought or could be a better place for all. I have the privilege of running two modules, one at level 4 Imagining Crime and one at Level 6 Violence. In both of these students work together to see the world differently, to imagine a world without violence, a world in which justice is a constant and reflection a continual practice. Walking into one of these classrooms you may well be surprised to see how thoughtful and passionate people can be when faced with a seemingly unsolvable problem when everything on the table is up for discussion. Although often misattributed to Einstein, the statement ‘Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results’ seems apposite. If we want the world to be different, we have to allow people to think about things differently, in free and safe spaces, so they can consider all perspectives, and that is where Criminology comes in.

Be fearless and unleash your criminological imagination, who knows where it might take you!

Taking a short break….back soon

The academic year 24/25 will shortly come to an end with the last assessments submitted and graded. Here at the Thoughts From the Criminology Team we’re going to take a little break before we jump back into planning for the new academic year. Don’t worry, we’ll be back with lots of interesting entries from August and after all, ‘absence makes the heart grow fonder’.

In the meantime, there’s plenty on the site to explore.

Enjoy your August whatever you are up to!

How to make a more efficient academic

Against a backdrop of successive governments’ ideology of austerity, the increasing availability of generative Artificial Intelligence [AI] has made ‘efficiency’ the top of institutional to-do-lists’. But what does efficiency and its synonym, inefficiency look like? Who decides what is efficient and inefficient? As always a dictionary is a good place to start, and google promptly advises me on the definition, along with some examples of usage.

The definition is relatively straightforward, but note it states ‘minimum wasted effort of expense’, not no waste at all. Nonetheless the dictionary does not tell us how efficiency should be measured or who should do that measuring. Neither does it tell us what full efficiency might look like, given the dictionary’s acknowledgement that there will still be time or resources wasted. Let’s explore further….

When I was a child, feeling bored, my lovely nan used to remind me of the story of James Watt and the boiling kettle and that of Robert the Bruce and the spider. The first to remind me that being bored is just a state of mind, use the time to look around and pay attention. I wouldn’t be able to design the steam engine (that invention predated me by some centuries!) but who knows what I might learn or think about. After all many millions of kettles had boiled and he was the only one (supposedly) to use that knowledge to improve the Newcomen engine. The second apocryphal tale retold by my nan, was to stress the importance of perseverance as essential for achievement. This, accompanied by the well-worn proverb, that like Bruce’s spider, if at first you don’t succeed, try, try again. But what does this nostalgic detour have to do with efficiency? I will argue, plenty!

Whilst it may be possible to make many tasks more efficient, just imagine what life would be like without the washing machine, the car, the aeroplane, these things are dependent on many factors. For instance, without the ready availability of washing powder, petrol/electricity, airports etc, none of these inventions would survive. And don’t forget the role of people who manufacture, service and maintain these machines which have made our lives much more efficient. Nevertheless, humans have a great capacity for forgetting the impact of these efficiencies, can you imagine how much labour is involved in hand-washing for a family, in walking or horse-riding to the next village or town, or how limited our views would be without access (for some) to the world. We also forget that somebody was responsible for these inventions, beyond providing us with an answer to a quiz question. But someone, or groups of people, had the capacity to first observe a problem, before moving onto solving that problem. This is not just about scientists and engineers, predominantly male, so why would they care about women’s labour at the washtub and mangle?

This raises some interesting questions around the 20th century growth and availability of household appliances, for example, washing machines, tumble driers, hoovers, electric irons and ovens, pressure cookers and crock pots, the list goes on and on. There is no doubt, with these appliances, that women’s labour has been markedly reduced, both temporally and physically and has increased efficiency in the home. But for whose benefit? Has this provided women with more leisure time or is it so that their labour can be harnessed elsewhere? Research would suggest that women are busier than ever, trying to balance paid work, with childcare, with housekeeping etc. So we can we really say that women are more efficient in the 21st century than in previous centuries, it seems not. All that has really happened is that the work they do has changed and in many ways, is less visible.

So what about the growth in technology, not least, generative AI? Am I to believe, as I was told by Tomorrow’s World when growing up, that computers would improve human lives immensely heralding the advent of the ‘leisure age’? Does the increase in generative AI such as ChatGPT, mark a point where most work is made efficient? Unfortunately, I’ve yet to see any sign of the ‘leisure age’, suggesting that technology (including AI) may add different work, rather than create space for humans to focus on something more important.

I have academic colleagues across the world, who think AI is the answer to improving their personal, as well as institutional, efficiency. “Just imagine”, they cry, “you can get it to write your emails, mark student assessment, undertake the boring parts of research that you don’t like doing etc etc”. My question to them is, “what’s the point of you or me or academia?”.

If academic life is easily reducible to a series of tasks which a machine can do, then universities and academics have been living and selling a lie. If education is simply feeding words into a machine and copying that output into essays, articles and books, we don’t need academics, probably another machine will do the trick. If we’re happy for AI to read that output to video, who needs classrooms and who needs lecturers? This efficiency could also be harnessed by students (something my colleagues are not so keen on) to write their assessments, which AI could then mark very swiftly.

All of the above sounds extremely efficient, learning/teaching can be done within seconds. Nobody need read or write anything ever again, after all what is the point of knowledge when you’ve got AI everywhere you look…Of course, that relies on a particularly narrow understanding which reduces knowledge to meaning that which is already known….It also presupposes that everyone will have access to technology at all times in all places, which we know is fundamentally untrue.

So, whatever will we do with all this free time? Will we simply sit back, relax and let technology do all the work? If so, how will humans earn money to pay the cost of simply existing, food/housing/sanitation etc? Will unemployment become a desirable state of being, rather than the subject of long-standing opprobrium? If leisure becomes the default, will this provide greater space for learning, creating, developing, discovering etc. or will technology, fueled by capitalism, condemn us all to mindless consumerism for eternity?

#UONCriminologyClub: What should we do with an Offender? with Dr Paula Bowles

You will have seen from recent blog entries (including those from @manosdaskalou and @kayleighwillis21 that as part of Criminology 25th year at UON celebrations, the Criminology Team have been engaging with lots of different audiences. The most surprising of these is the creation of the #UONCriminologyClub for a group of home educated children aged between 10-15. The idea was first mooted by @saffrongarside (who students of CRI1009 Imagining Crime will remember as a guest speaker this year) who is a home educator. From that, #UONCriminologyClub was born.

As you know from last week’s entry @manosdaskalou provided the introductions and started our “crime busters” journey into Criminology. I picked up the next session where we started to explore offender motivations and society’s response to their criminal behaviour. To do so, we needed someone with lived experience of both crime and punishment to help focus our attention. Enter Feathers McGraw!!!

At first the “crime busters” came out with all the myths: “master criminal” and “evil mastermind” were just two of the epithets applied to our offender. Both of which fit well into populist discourse around crime, but neither is particularly helpful for criminological study, But slowly and surely, they began to consider what he had done (or rather attempted to do) and why he might be motivated to do such things (attempted theft of a precious jewel). Discussion was fast flowing, lots of ideas, lots of questions, lots of respectful disagreement, as well as some consensus. If you don’t believe me, have a look at what Atticus and had to say!

We had another excellent criminology session this week, this time with Dr Paula Bowles. I think we all had a lot of fun, I personally could have enjoyed double or triple the session time. Dr Bowles was engaging, fun and unpretentious, making Criminology accessible to us whilst still covering a lot of interesting and complex subjects. We discussed so many different aspects of serious crime and moral and ethical questions about punishment and the treatment of criminals. During the session, we went into some very deep topics and managed to cover many big ideas. It was great that everyone was involved and had a lot to say. You might not necessarily guess from what I’ve said so far, how we got talking about Criminology in this way. It was all through the new Aardman animations film Wallace and Gromit: Vengeance Most Fowl and the cheeky little penguin or is it just a chicken? Feathers McGraw. Whether he is a chicken or a penguin, he gave us a lot to discuss such as whether his trial was fair or not since he can’t talk, if the zoo could really be counted as a prison and, if so was he allowed to be sent there without a trial? Deep ethical questions around an animation. Just like last time it was a fun and engaging lesson that made me want to learn more and more and I can’t wait for next time. (Atticus, 14)

What emerged was a nuanced and empathetic understanding of some key criminological debates and questions, albeit without the jargon so beloved of social scientists: nature vs. nurture, coercion and manipulation of the vulnerable, the importance of human rights, the role of the criminal justice system, the part played by the media, the impetus to punish to name but a few. Additionally, a deep philosophical question arose as to whether or not Aardman’s portrayal of Feathers’ confinement in a zoo, meant that as a society we treat animals as though they are criminals, or criminals as though they are animals. We are all still pondering this particular question…. After deciding as group that the most important thing was for Feathers to stop his deviant behaviour, discussions inevitably moved on to deciding how this could be achieved. At this point, I will hand over to our “crime busters”!

What to do with Feathers McGraw?

At first, I thought that maybe we should make prison a better place so that he would feel the need to escape less. It wouldn’t have to be something massive but just maybe some better furniture or more entertainment. Also maybe make the security better so that it would be harder to break out. If we imagine the zoo as the prison, animals usually stay in the zoo for their life so they must have done some very bad stuff to deserve a life sentence! Is it safe to have dangerous animals so close to humans? Feathers McGraw might get influenced by the other prisoners and instead of getting better he might get more criminal ideas. I believe there should be a purpose-built prison for the more dangerous criminals, so they are kept away from the humans and the non-violent criminals. in this case is Feathers considered a violent or non-violent criminal? Even though he hasn’t killed anyone, he has abused them, tried to harm them, hacked into Wallace’s computer, vandalised gardens through the Norbots, and stole the jewel. So, I think we should get a restraining order against Feathers McGraw to stop him from seeing Wallace and Gromit. I also think we should invest in therapy for Feathers to help him realise that he doesn’t need to own the jewel to enjoy it, what would he even do with it?! Maybe socializing could also help to maybe take his mind of doing criminal things. He always seems alone and sad. I’m not sure whether he will be able to change his ways or not but I think we should do the best we can to. (Paisley, 10)

I think in order to stop Feathers McGraw’s criminal behaviour, he should go to prison but while he is there, he should have some lessons on how to be good, how to make friends, how to become a successful businessman (or penguin!), how to travel around on public transport, what the law includes and what the punishments there are for breaking it etc. I also think it’s important to make the prisons hospitable so that he feels like they do care about him because otherwise it might fuel anger and make him want to steal more diamonds. At the same time though, it should not be too nice so that he’ll think that stealing is great, because if you don’t get caught, then you keep whatever you stole and if you do get caught then it doesn’t matter because you will end up staying in a luxury cell with silky soft blankets.

After he is released from prison, I would suggest he would be held under house arrest for 2-3 months. He will live with Wallace and Gromit and he will receive a weekly allowance of £200. With this money, he will spend:

£100 – Feathers will pay Wallace and Gromit rent each week,

£15-he will pay for his own clothes,

£5-phone calls,

£10-public transport,

£35-food,

£5-education,

£15-hygiene,

£15- socialising and misc.

During this time, Feathers could also be home educated in the subjects of Maths, English etc. He should have a schedule so he will learn how to manage his time effectively and eventually should be able to manage his timewithouta schedule. The reason for this is because when Feathers was in prison, he was told what to do every day and at what time he would do it. He now needs to learn how to make those decisions by himself. This would mean when his house arrest is finished, he can go out into the real world and live happy life without breaking the law or stealing. (Linus, 13)

I think that once Feathers McGraw has been captured any money that he has on him will be taken away as well as any disguises that he has and if he still has any belongings left they will be checked to see whether he can have them. After that he should go to a proper prison and not a Zoo, then stay there for 3 months. Once a week, while he is in prison a group of ten penguins will be brought in so that he can be socialised and learn manners and good behaviour from them. However they will be supervised to make sure that they don’t come up with plans to escape. After that he will live with a police officer for 3 years and not leave the house unless a responsible and trustworthy adult accompanies him until he becomes trustworthy himself. He will be taught at the police officers house by a tutor because if he went to school he might run away. Feathers McGraw will have a weekly allowance of £460 that is funded by the government as he won’t have any money. Any money that was taken away from him will be given back in this time. Any money left over will be put into his savings account or used for something else if the money couldn’t quite cover it.

In one week he will give

£60 for fish and food

£10 for travel

£50 for clothing but it will be checked to make sure that it isn’t a disguise.

£80 for the police officer that looking after him

£15 for necessities (tooth brush, tooth paste, face cloth etc…)

£70 for his tutor

£55 for education supplies

£20 will be put in a savings account for when he lives by himself again.

And £100 for some therapy

After 1 year if the police officer looking after him thinks that he’s trustworthy enough then he can get a job and use £40 pounds a week (if he earns manages to earn that much.) as he likes and the rest of it will be put into his savings account. Feathers McGraw will only be allowed to do certain jobs for example, He couldn’t be a police officer in case he steals something that he’s guarding, He also couldn’t be a prison guard in case he helped someone escape etc… If at any point he commits another crime he will lose his freedom and his job and will be confined to the house and garden. When he lives by himself again he will have to do community service for 1 month. (Liv, 11).

Feathers McGraw has committed many crimes, some of which include attempted theft, abuse towards Wallace and Gromit, and prison break.

Here are some ideas of things that we can do to stop him from reoffending:

Immediate action:

A restraining order is to be put in place so he can’t come within 50m of Wallace and Gromit, for their protection both physical and mental. Penguins live for up to 20 years so seeing as he is portrayed as being an adult, my guess is he is around 10 years old. His sentence should be limited to 2 years in prison. Whilst serving his sentence he should be given a laptop (with settings so that he can’t use it to hack) so he can write, watch videos, play games and learn stuff.

Longer term solutions:

When Feathers gets out he will be banned from seeing the gem in museums so there will be less chance of him stelling it. He also will be given some job options to help him get started in his career. His first job won’t be front facing so Wallace and Gromit won’t have to be worried and they will get to say no to any job Feathers tries to get. If he reoffends, he will be taken to court where his sentence will be a minimum of 5 years in prison.

Rehabilitation:

I think Feathers should be given rehabilitation in several different forms, some sneakier than others! One of these forms is probation: penguins which are trained probation officers who will speak to him and try to say that crime is not cool. To him they will look like normal penguins, he won’t know that they have had training. He also should be offered job experience so he can earn a prison currency which he can use to buy upgrades for his cell (for example a better bed, bigger tv, headphones, an mp3 player and songs for said mp3 player) to give him a chance to get a job in the future. (Quinn, 12)

The “crime busters” comments above came after reflecting on our session, their input demonstrates their serious and earnest attempt to resolve an extremely complex issue, which many of the greatest minds in Criminology have battled with for the last two centuries. They may seem very young to deal with a discipline often perceived as dark, but they show us an essential truth about Criminology, it is always hopeful, always focused on what could be, instead of tolerating what we have.

A Love Letter to Criminology at UON

In 2002, I realised I was bored, I was a full-time wife and parent with a long-standing part-time job in a supermarket. I first started the job at 15, left at 18 to take up a job at the Magistrates’ court and rejoined the supermarket shortly after my daughter was born. My world was comfortable, stable and dependable. I loved my family but it was definitely lacking challenge. My daughter was becoming increasingly more independent, I was increasing my hours and moving into retail management and I asked myself, is this it? Once my daughter had flown the nest, could I see myself working in a supermarket for the rest of my life? None of this is to knock those those that work in retail, it is probably the best training for criminology and indeed life, that anyone could ask for! I got to meet so many people, from all backgrounds, ethnicities, ages, religions and classes. It taught me that human beings are bloody awkward, including myself. But was it enough for me and if it wasn’t, what did I want?

At school, the careers adviser suggested I could work in Woolworths, or if I tried really hard at my studies and went to college, I might be able to work for the Midland Bank (neither organisation exists today, so probably good I didn’t take the advice!). In the 1980s, nobody was advocating the benefits of university education, at least not to working-class children like me. The Equal Pay Act might have been passed in 1970 but even today we’re a long way from equality in the workplace for women. In the 1980s there was still the unwritten expectation (particularly for working class children from low socio economic backgrounds) that women would get married, have children and perhaps have a part-time job but not really a career….I was a textbook example! I had no idea about universities, knew nobody that had been and assumed they were for other people, people very different from me.

That changed in 2002, I had read something in a newspaper about a Criminology course and I was fascinated. I did not know you could study something like that and I had so many questions that I wanted to answer. As regular readers of the blog will know I’m a long-standing fan of Agatha Christie whose fiction regularly touches upon criminological ideas. Having been born and raised in North London, I was very familiar with HMP Holloway’s buildings, both old and new, which raised lots of questions for a curious child, around who lived there, how did they get in and out and what did they do to the women held inside. Reading suffragette narratives had presented some very graphic images which further fed the imagination. Let’s just say I had been thinking about criminology, without even knowing such a discipline existed.

Once I was aware of the discipline, I needed to find a way to get over my prejudices around who university was for and find a way of getting in! To cut a long story short, I went to an Open Day and was told, go and get yourself an access course. At the time, it felt very blunt and reinforced my view that universities weren’t for the likes of me! Looking back it was excellent advice, without the access course, I would never have coped, let alone thrived, after years out of education.

In 2004 I started reading BA Criminology, with reading being the operant word. I had been an avid reader since early childhood (the subject of an earlier blog) and suddenly I was presented with a license to read whatever and whenever I wanted and as much as I could devour! For the first time in my life, people could no longer insist that I was wasting time with my head always in a book, I had “official” permission to read and read, I did! I got the chance to read, discuss, write and present throughout the degree. I wrote essays and reports, presented posters and talked about my criminological passions. I got the chance to undertake research, both empirical and theoretical, and lawks did I revel in all this opportunity. Of course, by looking back and reflecting, I forget all the stresses and strains, the anxieties around meeting so many new people, the terror of standing up in front of people, of submitting my first assessment, of waiting for grades….but these all pale into insignificance at the end and three years goes so very quickly….

In the summer of 2007, I had a lovely shiny degree in Criminology from the University of Northampton, but what next? By this point, I had the studying bug, and despite my anticipation that university would provide all the answers, I had a whole new set of questions! These were perhaps more nuanced and sophisticated than before but still driving me to seek answers. As I said earlier, human beings are awkward and at this point I decided, despite my earlier passion, I didn’t want to be put in a box labelled “Criminology“. I felt that I had finally cracked my fear of universities and decided to embark on a MA History of Medicine at Oxford Brookes. I wanted to know why Criminology textbooks and courses still included the racist, sexist, disablist (and plenty more) “theories” of Cesare Lombroso, a man whose ideas of the “born criminal” had been discredited soon after they were published.

But again the old fears returned….what did I know about history or medicine? What if the Criminology degree at Northampton hadn’t been very good, what if they just passed everyone, what if I was kidding myself? Everything at Brookes felt very different to Northampton, everyone on the course had studied BA History there. Their research interests were firmly centred on the past and on medicine, nursing, doctoring, hospitals and clinics and there was me, with my ideas around 20th century eugenics, a quasi-scientific attempt to rationalise prejudice and injustice. Along with studying the discipline, I learnt a lot about how different institutions work, I compared both universities on a regular basis. What did I like about each, what did I dislike. i thought about how academics operate and started to think about how I would be in that profession.

I successfully completed the MA and began to think maybe Northampton hadn’t given me good grades out of our pity or some other misplaced emotion, but that I had actually earnt them. I was very fortunate, I had maintained connection with Criminology at UON, and had the opportunity to tip my toe in the water of academia. I was appointed as an Associate Lecturer (for those not familiar with the title, it is somebody who is hourly paid and contribute as little or as much as the department requires) and had my first foray into university teaching. To put it bluntly, I was scared shitless! But, I loved every second in the classroom, I began to find my feet, slowly but surely, and university which had been so daunting began to seep into my very being.

Fast forward to 2025, I have been involved with UON for almost 22 years, first as a student, then as an academic, achieving my PhD in the process It is worth saying that the transition is not easy, but then nothing worth having ever is. I have gained so much from my studies, my relationship with two universities and the experiences I have had along the way. It is fair to say that I have shed many tears when studying, but also had some of my very highest highs, learning is painful, just watch a small child learning to read or write.

Hopefully, over the past decades I have repaid some of the debt I owe to the academics that have taught me, coached me, mentored me and supported me (special mention must go to @manosdaskalou who has been part of my journey since day 1). My life looks very different to 2002 and it is thanks to so many people, so many opportunities, the two universities that have provided me with a home from home and all of the students I have had the privilege to engage with.

I am so delighted to have been part of Criminology at UON’s 25 years of learning and teaching. To my colleagues, old and new, students, graduates and everyone I have met along the way, I raise my glass. Together we have built something very special, a community of people committed to exploring criminological ideas and making the world an equitable place.

Criminology for all (including children and penguins)!

As a wise woman once wrote on this blog, Criminology is everywhere! a statement I wholeheartedly agree with, certainly my latest module Imagining Crime has this mantra at its heart. This Christmas, I did not watch much television, far more important things to do, including spending time with family and catching up on reading. But there was one film I could not miss! I should add a disclaimer here, I’m a huge fan of Wallace and Gromit, so it should come as no surprise, that I made sure I was sitting very comfortably for Wallace & Gromit: Vengeance Most Fowl. The timing of the broadcast, as well as it’s age rating (PG), clearly indicate that the film is designed for family viewing, and even the smallest members can find something to enjoy in the bright colours and funny looking characters. However, there is something far darker hidden in plain sight.

All of Aardman’s Wallace and Gromit animations contain criminological themes, think sheep rustling, serial (or should that be cereal) murder, and of course the original theft of the blue diamond and this latest outing was no different. As a team we talk a lot about Public Criminology, and for those who have never studied the discipline, there is no better place to start…. If you don’t believe me, let’s have a look at some of the criminological themes explored in the film:

Sentencing Practice

In 1993, Feathers McGraw (pictured above) was sent to prison (zoo) for life for his foiled attempt to steal the blue diamond (see The Wrong Trousers for more detail). If we consider murder carries a mandatory life sentence and theft a maximum of seven years incarceration, it looks like our penguin offender has been the victim of a serious miscarriage of justice. No wonder he looks so cross!

Policing Culture

In Vengeance Most Fowl we are reacquainted with Chief Inspector Mcintyre (see The Curse of the Were-Rabbit for more detail) and meet PC Mukherjee, one an experienced copper and the other a rookie, fresh from her training. Leaving aside the size of the police force and the diversity reflected in the team (certainly not a reflection of policing in England and Wales), there is plenty more to explore. For example, the dismissive behaviour of Mcintyre toward Mukherjee’s training. learning is not enough, she must focus on developing a “copper’s gut”. Mukherjee also needs to show reverence toward her boss and is regularly criticised for overstepping the mark, for instance by filling the station with Wallace’s inventions. There is also the underlying message that the Chief Inspector is convinced of Wallace’s guilt and therefore, evidence that points away from should be ignored. Despite this Mukherjee retains her enthusiasm for policing, stays true to her training and remains alert to all possibilities.

Prison Regime

The facility in which Feathers McGraw is incarcerated is bleak, like many of our Victorian prisons still in use (there are currently 32 in England and Wales). He has no bedding, no opportunities to engage in meaningful activities and appears to be subjected to solitary confinement. No wonder he has plenty of time and energy to focus on escape and vengeance! We hear the fear in the prison guards voice, as well as the disparaging comments directed toward the prisoner. All in all, what we see is a brutal regime designed to crush the offender. What is surprising is that Feathers McGraw still has capacity to plot and scheme after 31 years of captivity….

Mitigating Factors

Whilst Feathers McGraw may be the mastermind, from prison he is unable to do a great deal for himself. He gets round this by hacking into the robot gnome, Norbot. But what of Norbot’s free will, so beloved of Classical Criminology? Should he be held culpable for his role or does McGraw’s coercion and control, renders his part passive? Without, Norbot (and his clones), no crime could be committed, but do the mitigating factors excuse his/their behaviour? Questions like this occur within the criminal justice system on a regular basis, admittedly not involving robot gnomes, but the part played in criminality by mental illness, drug use, and the exploitation of children and other vulnerable people.

And finally:

Above are just some of the criminological themes I have identified, but there are many others, not least what appears to be Domestic Abuse, primarily coercive control, in Wallace and Gromit’s household. I also have not touched upon the implicit commentary around technology’s (including AI’s) tendency toward homogeneity. All of these will keep for classroom discussions when we get back to campus next week 🙂

Season’s Greetings

The Thoughts from the Criminology Team would like to wish all our readers and writers happy holidays. We’d also like to extend our thanks to everyone for your contributions, without you there would not be a blog and they are very much appreciated.

Wherever you are in the world and whether or not you celebrate Christmas, we extend our good wishes to you and wish you and yours a peaceful end to 2024. We’ll be back in 2025 with lots more criminological content, until then stay safe and well.