My Calling in Life

I used to think waking up for lectures was the hardest thing in life. Little did I know that the 9am until 5pm isn’t a joke!

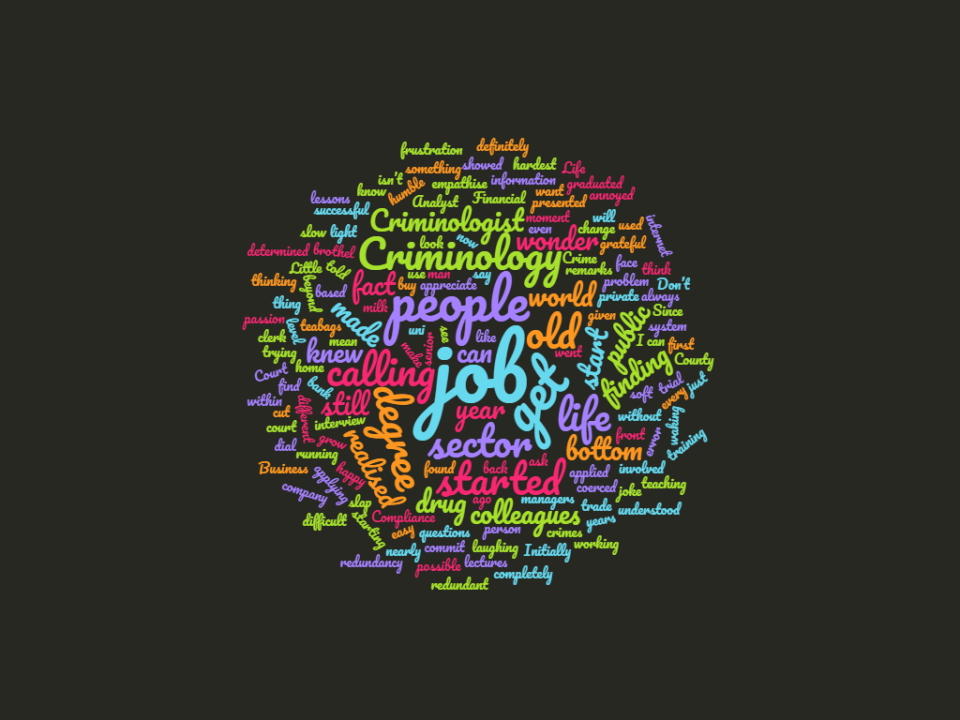

I graduated nearly 3 years ago now. Since then I have been trying to find my ‘calling’ in life. The world showed me it is not always easy finding this calling. If you want something you have to go and get it. Having a degree does not mean you will be successful. I had to start from the bottom and through trial and error; I can say I am starting to get there. Initially I was applying for any and every job possible. My first job was for an IT and Business training company and I was made redundant. That was difficult. Here I was thinking redundancy is for old people. Life had just started teaching its lessons.

After that I realised my passion was Criminology and I was determined in finding a job within this sector. So I started working for my County Court as clerk. I realised that I was definitely not cut out for the public sector. The frustration from the public because the court system is so slow (which I completely understood I would have been annoyed too). Don’t even get me started on the fact that I had to use dial up internet and buy my own teabags and milk! From that moment on I knew I had to get back into the private sector but still have a job in Criminology

I applied for a job as a Financial Crime Analyst for a bank and I was given the job without an interview! I knew I had found my ‘calling’. It is more Compliance based. I have had to start from the bottom. My senior managers appreciate the fact that I have a Criminology degree. But my colleagues make remarks like “Oh, you went to uni and we are still at the same level”. It is a slap in the face. But I am grateful for my degree. It has made me humble and look at people in a different light. When my colleagues are laughing at the crimes people commit such as an 80 year old man being involved in the drug trade or an 18 year old running a brothel. As a Criminologist I can ask questions such as “I wonder if this person is being coerced into this” or “I wonder if they have an drug problem or they did not grow up in a happy home”. I can empathise with these people and see beyond the information that is presented in front of me. I have been told I am too soft. But that is the life of a Criminologist and I would not change it for the world!

‘Leaving that to one side’ – Managing the too difficult

I love horology, my passion is antique grandfather clocks. My pride and joy stands in the hallway of my home. Lovingly restored, it makes me smile when it strikes on the hour. Each strike reminds me of the time and effort I put into getting it to work. I’m reminded of the trials and tribulations of having to understand how it worked, what was wrong with it and how to fix it. I have become quite adept at fixing clocks, I understand them, I know them. Each part of the clock has a specific job, each part is dependent on another, each part makes it a clock that works. From the smallest cog to the largest, take any one of them away and the clock no longer functions. It is the same for all time pieces, whether they are driven by weights, springs, or battery. They all have intrinsic parts that make them function, that are inter dependent.

I love horology, my passion is antique grandfather clocks. My pride and joy stands in the hallway of my home. Lovingly restored, it makes me smile when it strikes on the hour. Each strike reminds me of the time and effort I put into getting it to work. I’m reminded of the trials and tribulations of having to understand how it worked, what was wrong with it and how to fix it. I have become quite adept at fixing clocks, I understand them, I know them. Each part of the clock has a specific job, each part is dependent on another, each part makes it a clock that works. From the smallest cog to the largest, take any one of them away and the clock no longer functions. It is the same for all time pieces, whether they are driven by weights, springs, or battery. They all have intrinsic parts that make them function, that are inter dependent.

My clock, to anyone else, is a grand functioning timepiece. They would have little or no knowledge of the inner workings, save perhaps, they would know there were inner workings. Perhaps too complicated to understand, the workings would have no significance to them unless they owned the clock and then only if the clock didn’t function, kept stopping or perhaps was running a little slow or a little fast owing to some fault.

Compare the clock to an organisation, the workings are the departments, units or what ever you want to call them. The manager is the owner, the person that winds the clock up, occasionally ensures it is cleaned, even serviced, they make sure it works and works correctly. The manager might decide they no longer wish the clock to chime and they have that part of the mechanism removed. Perhaps they no longer want the clock to have a second hand, that too can be removed, even the minute hand. It would still be recognisable as a time piece. Organisations go through such changes all the time. Who though would the manager call on to make these alterations? Who would advise what is best? A specialist of course, someone who knows the inner workings of the clock, who understands how it works, who understands that some pieces can be removed and that others cannot. Well not if it is still to function as a time piece rather than a useless lump of furniture in the corner. Of course, if the inner workings of the clock could talk, each would be able to tell you what their function is. If you want to make alterations to the clock, you need to understand how it functions, not just that it functions.

Understanding what the right thing to do is often difficult for managers in organisations particularly when dealing with change. They pride themselves on seeing the bigger picture, sometimes they do, sometimes it’s simply a mirage. And like departments in organisations, the chime, the second hand and the minute hand, with all their associated mechanisms would argue that they are needed, that somehow the clock would fail if they were not there. The manager believes this is not the case and dismisses such protests. But such are the intricacies of the inner workings that knowing what will cause something to fail and what won’t is often difficult to discern. When an expert tells you that a cog in the timepiece is failing do you leave it to one side or address it? Do you bury your head in the sand and hope the problem will go away? A good manager listens, a good manager discerns what is important and what is not. A good manager recognises that there are times when understanding the implications of a faulty cog are more important than the grand vision (or mirage). But that means sometimes getting into the workings of the clock, being shown how it functions and understanding what the problem really is. If you want to maintain some sort of time piece, as a manager, you cannot afford to simply ‘leave things to one side’. Ignoring issues because you don’t understand them or you only see the mirage will leave you in a void where time has stopped.

The Next Step: Life After University

My name is Robyn Mansfield and I studied Criminology at the University of Northampton from 2013 to 2016. In 2016 I graduated with a 2:2. The University of Northampton was amazing and I learnt some amazing things while I was there. I learnt many things both academic and about myself. But I honestly had no idea what I wanted to do next. I went to University wanting to be a probation officer, but I left with no idea what my next step would be and what career I wanted to pursue.

My first step after graduating was going full-time in retail because like most graduates I just needed a job. I loved it but I realised I was not utilising my degree and my full potential. I had learnt so much in my three years and I was doing nothing with my new knowledge. I started to begin to feel like I had wasted my time doing my degree and admitting defeat that I’d never find a job that I would use my degree for. I decided to quit my job in retail and relocate back to my hometown.

I was very lucky and fell into a job working in a High School that I used to attend after I quit my retail job. I became a Special Educational Needs Teaching Assistant and Mentor. I honestly never thought that I’d be working with children after University, but the idea of helping children achieve their full potential was something that stood out to me and I really wanted to make a difference. The mentoring side was using a lot that I’d learnt at University and I really felt like I was helping the children I worked with.

I am currently an English Learning Mentor at another school. I mentor a number of children that I work with on a daily basis. As part of my role I cover many pastoral issues as well. I am really enjoying this new role that I am doing.

Eventually, in the short-term I would love to do mentoring as my full role or maybe progress coaching in a school. In the long-term I would love to become a pastoral manager or a head of year. The work I have been doing is all leading up to me getting the experience I need to get me to where I want to be in the future.

The best advice I would give to people at University now or who have graduated is not to worry if you have no idea what you want to do after you’ve got your degree. You might be like me, sat at University listening to what everyone else has planned after University; travelling, jobs or further education. Just enjoy the University experience and then go from there. I had no idea what I was doing and at certain points I had no job for months. But in a months time, a years time or longer you will finally realise what you want to do. It took me doing a job I never expected I would do to realise what I wanted to do with my degree.

Graduation: the end of the beginning?

Helen is an Associate Lecturer teaching on modules in years 1 and 3.

I joined the University of Northampton as an associate lecturer in 2009, teaching at first on the Offender Management foundation degree and then joining the Criminology team, although I had been a visiting lecturer in Criminology for a number of years prior to that. I am sorry that a prior commitment means that I am unable to join you for the Big Criminology Reunion, although the occasion has inspired me to reflect on the professional journey that starts with graduation.

Last week I received an e-mail from a former student in the 2010 Offender Management cohort. She is just about to qualify as a probation officer and she was asking for advice about giving evidence at Parole Board hearings. It was great to think back, to remember what a vibrant and enthusiastic student she was, and to project forwards; perhaps I’ll see her at an oral hearing soon. She will probably make an excellent probation officer, and the fact that she is asking for advice before she even starts is evidence of that. She will possibly be the first of our offender management students to become an offender manager!

A couple of years ago I was at a Parole Hearing at HMYOI Aylesbury where I was very impressed by the evidence of the trainee psychologist. She had prepared a clear, concise but thorough and analytical report on the prisoner and she gave her oral evidence confidently and thoughtfully. After the end of the hearing, she popped back in to tell me that she had been initially inspired to take up prison psychology after hearing my guest lecture on Manos’ Forensic Psychology module. I saw her again earlier this year and she’s still doing a great job!

For undergraduates, completing a degree, submitting a dissertation, putting the pen down at the end of the last exam and then graduating with friends, seems like the end of a long and arduous process. And of course it is! But as the stories above show, it is also just the beginning. Just the beginning of a professional journey which may or may not involve direct application of the subjects covered on the course. Not all our students become probation officers or prison psychologists or academic criminologists, but they will take something of what they learn out into the world with them. It may be a more critical way of digesting the news, a wider appreciation of the social forces that shape our world, a readiness to reflect and question and see the world from different perspectives. All of that will help them on their journey. I hope that you all have a great time at the reunion and that as you compare each other’s journeys you have fond memories of the degree course that seemed a marathon at the time but was really only the first step!

(In)Human Rights in the “Compliant Environment”

In the aftermath of the Windrush generation debacle being brought into the light, Amber Rudd resigned, and a new Home Secretary was appointed. This was hailed by the government as a turning point, an opportunity to draw a line in the sand. Certainly, within hours of his appointment, Sajid Javid announced that he ‘would do right by the Windrush generation’. Furthermore, he insisted that he did not ‘like the phrase hostile’, adding that ‘the terminology is incorrect’ and that the term itself, was ‘unhelpful’. In its place, Javid offered a new term, that of; ‘a compliant environment’. At first glance, the language appears neutral and far less threatening, however, you do not need to dig too deep to read the threat contained within.

According to the Oxford Dictionary (2018) the definition of compliant indicates a disposition ‘to agree with others or obey rules, especially to an excessive degree; acquiescent’. Compliance implies obeying orders, keeping your mouth shut and tolerating whatever follows. It offers, no space for discussion, debate or dissent and is far more reflective of the military environment, than civilian life. Furthermore, how does a narrative of compliance fit in with a twenty-first century (supposedly) democratic society?

The Windrush shambles demonstrates quite clearly a blatant disregard for British citizens and implicit, if not, downright aggression. Government ministers, civil servants, immigration officers, NHS workers, as well as those in education and other organisations/industries, all complying with rules and regulations, together with pressures to exceed targets, meant that any semblance of humanity is left behind. The strategy of creating a hostile environment could only ever result in misery for those subjected to the State’s machinations. Whilst, there may be concerns around people living in the country without the official right to stay, these people are fully aware of their uncertain status and are thus unlikely to be highly visible. As we’ve seen many times within the CJS, where there are targets that “must” be met, individuals and agencies will tend to go for the low-hanging fruit. In the case of immigration, this made the Windrush generation incredibly vulnerable; whether they wanted to travel to their country of origin to visit ill or dying relatives, change employment or if they needed to call on the services of the NHS. Although attention has now been drawn to the plight of many of the Windrush generation facing varying levels of discrimination, we can never really know for sure how many individuals and families have been impacted. The only narratives we will hear are those who are able to make their voices heard either independently or through the support of MPs (such as David Lammy) and the media. Hopefully, these voices will continue to be raised and new ones added, in order that all may receive justice; rather than an off-the-cuff apology.

However, what of Javid’s new ‘compliant environment’? I would argue that even in this new, supposedly less aggressive environment, individuals such as Sonia Williams, Glenda Caesar and Michael Braithwaite would still be faced with the same impossible situation. By speaking out, these British women and man, as well as countless others, demonstrate anything but compliance and that can only be a positive for a humane and empathetic society.

Another broken promise – Ministry of Justice announcement to postpone plans to reduce female prison population

The plight of women in prison aptly demonstrates some of the issues I have with our current government. There seems to be a pattern of u-turns, postponing on strategies and little remorse or concern shown for the impact of these decisions. Now I don’t know if this is to do with focus on Brexit, or some other reason that only those in the corridors of power can know. What I am concerned about is the cavalier way this government back tracks and displays levels of incompetency that anyone else would be sacked for. I am concerned because these tactics affect lives, they impact on people’s health wellbeing and survival. Women in prison suffer disproportionately compared to men, and it seems, they are easy target to disregard. They are also a prison population which is predominantly low risk and would benefit from assistance, welfare and support, much more so than punishment and retribution. By the way, I also firmly believe there are plenty of male prisoners and young offenders in the same boat – as do others. Women in prison, including those who are also mothers (up to 66%) (Epstein, 2014) do however face greater impact for a variety of reasons. It is these reasons which make the recent announcement by the Ministry of Justice to postpone plans to reduce the female prison population all the more galling.

An article in the Guardian states ‘women account for 5% of the prison population of in England and Wales but have much higher rates of deaths, suicide attempts and self-harm than men’ (Syal, 2018). The focus of the multimillion pound government strategy to reduce the number of women being imprisoned for non-violent offences was to set up community prisons and provide more support for female offenders. The postponement was reported to be due to spending pressures, which is also affected spending on the prison system more widely. This is a strategy which has been developed over several years and this postponement must surely test the patience of those reformers who have campaigned for this change. Indeed, Peter Dawson, the director of the Prison Reform Trust has expressed disbelief that a strategy which had widespread support is being treated in this way. He also added that to cite the postponement as an issue with cost is contradictory, given better support in the community and the aims of the strategy to reduce the numbers of women in prison would actually reduce costs to the Ministry of Justice. Women prisoners have complex needs, with mental health issues, abuse, debt, homelessness, poor education as well a significant number having child care responsibilities and with a prison sentence, facing the very real prospect of losing their child to the social care system (Baldwn, 2017).

The MoJ strategy embraced multi-agency working and even found a way to navigate achieving its aims under the current Transforming Rehabilitation arrangements, with the National Probation Service working with the police, mental health charities and courts to co-ordinate better support services and better arrangements to help women due for release. The need for this was clear as a report by Inquest (2018) showed that 116 women died post release during 2010-11 and 2016-17. In addition to increased incidences of self-harm and suicides, and given that 84% of women are imprisoned for non-violent offences (ibid), it was clear that not only should something be done, but also that something could be done. The benefits were evident in saving money, reducing risks to women prisoners and not compromising on public protection. The report by Inquest (2018) also shows that the disproportionate number of women on short term sentences (62%) reiterates the need to reduce this, given the disruptive effects on housing, jobs and childcare. Deborah Coles of Inquest suggest this postponement by the MoJ will costs lives and that the harms of the justice system to women need to be acknowledged.

This need for change is also supported by the Magistrates Association, who also report that help and support is much more effective than short term sentences. Given this arena is where the decision to sentence occurs, it is an important move to get magistrates thinking differently about the delivery of justice. This is not just about considering community sentences, but also to consider how the court room can be a place for different approaches to those offenders – male or female – who present complex needs, experiences of abuse and discrimination and who require more than stern words and retributive acts of punishment.

There have long been concerns about the rising numbers of female prisoners, given that this is attributed to increasing punitiveness in sentencing decisions (Hedderman, 2004). There is a strong case for using community sentencing where this is appropriate (Corston, 2007; Prison Reform Trust 2011; Baldwin, 2015), i.e. for non-violent and low risk offenders. This is evidence from campaigns (e.g. from the Howard League for Penal Reform, the Prison Reform Trust, Women in Prison, Make Justice Work) to reduce the use of custody more generally, but especially for women and mothers who break the law. A recent edited text on the plight of mothers in prison further emphasises the need for a different approach (Baldwin, 2015). It collates contributions from academics and practitioners working within the prison system, managing the needs of mothers and mothers to be, as well as those research these issues (e.g. Baldwin, 2015; Epstein, 2012; Minson 2014). A core theme is that short term sentences create a narrative of continuing disadvantage, felt for generations (Baldwin, 2015). It also demonstrates the long-term effects of the imprisonment of mothers, as a ripple effect which impacts the mother, their child, other family members for a length of time way past the length of the sentence – what Baldwin (2015) has referred to as a ‘sentence which keeps on punishing’. This text reiterates the potential for change starting with the courts, where different approaches would have a lasting impact and lead to more positive outcomes.

This is just the tip of the iceberg in terms of evidence which shows a different way to deal with offenders is possible, the evidence is there, the options are there and until recently, some degree of political will and investment was also there. I hope this is a postponement and not just another broken promise. This seems to be a pattern for this government, and there seems to be no one holding them to account when such decisions are made. It may well be because the prison population is a group we can all too easily disregard. However, given that these are people who have faced a life of disadvantage and whose reformation would benefit all of us who wish to feel safe in our communities, this view is misguided. The problem is, it seems it is all too easily accepted.

References

Baldwin, L. (2015) Mothering Justice: Working with Mothers in Criminal and Social Justice Settings, Waterside Press.

Baldwin, L. (2015d). Rules of Confinement: Time for Changing the Game. Criminal Law and Justice Weekly, 179 (10).

Corston, J. (2007). The Corston Report: A report by Baroness Jean Corston of a Review of Women with Particular Vulnerabilities in the Criminal Justice System. London: Home Office.

Epstein, R. (2014). Mothers in Prison: The sentencing of mothers and the rights of the child, Howard League What is Justice? Working Papers 3/2014, Howard League for Penal Reform.

Hedderman, C. (2004). The ‘criminogenic’ needs of women offenders. In G. McIvor

(ed) Women Who Offend: Research Highlights in Social Work 44. London: Jessica

Kingsley Publishers.

Inquest (2016) Still Dying On The Inside: Examining deaths in women’s prisons (see https://www.inquest.org.uk/Handlers/Download.ashx?IDMF=8d39dc1d-02f7-48eb-b9ac-2c063d01656a)

Minson, S. (2014). Mitigating Motherhood: A study of the impact of motherhood on sentencing decisions in England and Wales, Howard League for Penal Reform, London.

Prison Reform Trust (2011). Reforming Women’s Justice: Final Report of the Women’s Justice Taskforce. London: Prison Reform Trust.

Syal, R. (2018) Ministry of Justice postpones plans to reduce female prison population, The Guardian, 2 May 2018.