Erasmus in the time of Brexit

There are few things I tend to do when I am on Erasmus in a long running partner. I get a morning fredo coffee from their refectory, then into the classroom, followed by a brief chat with their administration staff and colleagues. The programme is usually divided between teaching sessions and academic discussions.

My last session was on learning disabilities and empowerment. The content forms part of a module on people with special needs. The curriculum in the host institution combines social sciences differently and therefore my hard criminological shell is softened during my visit. It is also interesting to see how sciences and disciplines are combined together and work in a different institution.

In the first two hours we were talking about advocacy and the need for awareness. The questions posed by the students raised issues of safeguarding, independence and the protection of the people with learning disabilities. I posed a few dilemmas and the answers demonstrated the difficulties and frustrations we feel beyond academia, shared among practitioners. This is “part of the issues professionals face on a daily basis”. Then there were some interesting conversations “how can you separate a mother from her baby even if there are concerns regarding her suitability as a mum”? “How do we safeguard the rights of people who cannot live an independent life”? Then we discussed wider educational concerns “we are preparing for our placement but we are not sure what to expect”. “Interesting”, I thought that is exactly what my second year students feel right about now.

As I was about to close the session I told them the thought that has been brewing at the back of my head since the start of my visit….”I may not be able to see you next year…today the UK will be starting the process of Brexit.” One of the students gasped the rest looked perplexed.

It is the kind of look I am beginning to become accustomed to every time I talk about Brexit to people on the continent.

After the class the discussion with colleagues and administrative staff was on Brexit. It seemed that each person had their own version of what will happen next. Ironically they assumed that I knew more about it. Thinking about it, the process is now activated but very little is known. This is because Brexit is actually not a process but a negotiation. A long or a very long negotiation. The EU devised a mechanism of exit but not a process that this mechanism needs to follow. Despite the reasons why we are leaving the EU the order and the issues that this will leave open are numerous. In HE, we are all still considering what will happen once the dust settles. From research grants for the underfunded humanities and social sciences to mobility programmes for academics and students. My visit was part of staff mobility that allows colleagues to teach and exchange knowledge away from their institution. The idea was to allow the dissemination of different ideas, cooperation and cultural appreciation of different educational systems. The programme was originally set up in the late 80s when the vision for European integration was alive and kicking. The question which emerges now, post-Brexit, is what is the wider vision for HE?

Who am I? Single Parent vs Academic

Who am I? For this week’s blog I thought I’d talk about the challenges of being a single parent and an academic. When I started down this path, children were definitely not part of my plan. I was career driven and adamant that I was going to be an outstanding academic – how things change! As others around me started to settle down and have children I found myself increasingly being challenged by societal perceptions that as ‘a women’ it was my duty to have children, if for no other reason than to have someone to look after me when I got old. I vividly remember these conversations, with people saying ‘you need to make a decision’, or ‘you can’t have both (children and a career)’! For those of you who know me, you’ll know that being told I ‘can’t’ do something simply makes me more determined to prove everyone wrong, however what I hadn’t taken into account was the fact that I’d eventually end up doing it on my own. So here I am some years later trying to balance the two. Do I do it successfully? Well that depends on how you measure success. From an academic perspective the answer’s probably no because I’ve deviated a long way from my original goal. Similarly, if being a good parent is someone who is there for the children after school, every weekend, and school holidays then the answer is also no. In short, trying to do both presents a constant state of tension, with my job demanding evening and weekend work, and my kids demanding less commitment to my career. For many, the answer to this tension is simply a matter of prioritising my children over my career, however what happens when my children grow up and my career has stalled? Also, why should I have to lose myself and my dreams in the name of motherhood? Such questions lead to feelings of guilt, guilt because I’m not there to collect the kids from school like the other mums in my area, guilt because I can’t commit to networking and conference because of the absence of childcare, guilt for taking time to go to sports day, Christmas plays, recitals and the like, rather than finishing that paper for publication.

Mulling this over I’ve come to the conclusion that there is no answer, in fact the situation is only likely to get worse as greater and greater pressures are placed on us in both our work and home environments. But all is not lost, as human beings we have considerable resilience, so I make it work through a process of negotiation and compromise. The children are well accustomed to the rule that ‘mummy works in the morning and plays in the afternoon’. They also get my full attention for a 2 hours every evening, restricting my work to after they have gone to bed. My most cunning approach is the one that involves play zones, where they can run around and burn energy and I can work in the corner with a cuppa tea. Finally, it’s about picking out the moments that are most important to them such as gymnastic recitals, swimming lessons, sports days and all the performances, which to them are huge events. I’m lucky that the nature of what I do allows me the freedom to be able to attend these big childhood events and gain brownie points in their eyes, which then minimises the impact of my absence at other times. The same compromises have been made regarding my career, I’ve adjusted my goals and dreams making them more realistic for my current situation. I’ll still be a good academic but I may never be a high flyer, but I’m happy with that – for now!

The Commodification of Abstinence

The inspiration for this short blog post comes from an incredibly stimulating discussion with some of my second year students studying the criminology module ‘Outsiders’. In class we were discussing how rather than constituting active forms of rebellion that resist the mainstream, various ‘trendy’ acts of so-called deviance, such as graffiti, parkour and ‘rooftopping’, have actually become absorbed into the mainstream consumer culture. Following this we began to discuss ‘new’ ways of resisting. Amongst the ideas offered was the notion of somehow disconnecting ourselves from the now ever-present network of social media and its frequent and avid advertisement of consumer items. Interestingly, having already discussed the tendency for social media’s ‘revolutionary potential’ to be integrated within rather than threaten capitalism (Crary 2013), this proposed disconnect would also require avoiding the latest online driven micro-revolution. The result of this discussion was the idea of ‘going mobile free for a week’.

The problem with this proposed ‘period of abstinence’ is that it becomes another micro-revolution that simply represents a new opportunity for commodification. This is because capitalism has the uncanny ability “to incorporate every attack by integrating the attack into the system” (McGowan 2016:12). It does this by taking the seemingly revolutionary practice and transforming it into a marketable commodity. With this in mind, we started to consider how such periods of abstinence would be integrated and commodified. It was suggested that a number of high-street retailers such as Game and HMV would perhaps have preparatory sales the week before to help us cope with the inevitable upset of ‘going mobile free for a week’. Similar offers would no doubt be made by a range of other providers; why not get into cycling, mountain climbing, or Zumba? That is after buying all the essential gear and merchandise of course. Then, once this period of abstinence is over, what better way to show how ‘resistant’ you were than by posting pictures of, or tweeting about, all the things you got up to during this ‘rebellious’ period; thereby further contributing to the marketing of consumer items.

Rather than representing some form of resistance then, this period of abstinence becomes commodified and successfully integrated into contemporary consumer capitalism. This does not mean that there is no alternative to capitalism, it simply means that if we wish to make a genuine attempt at resistance we should avoid being absorbed or forced into the next ‘trendy’ micro-revolution or simulated rebellion (Hall et al. 2008). Precisely how we do this is of course another matter entirely.

Justin Kotzé, March 2017

References

Crary, J. (2013) 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep. London: Verso.

Hall, S., Winlow, S. and Ancrum, C. (2008) Criminal Identities and Consumer Culture: Crime, Exclusion and the New Culture of Narcissism. Cullompton: Willan Publishing.

McGowan, T. (2016) Capitalism and Desire: The Psychic Cost of Free Markets. New York: Columbia University Press.

(The Absence of) Technology in the Classroom

Following on from Manos’ ‘Reflections from a pilot’ I shall continue in a similar vein. The pilot has formed part of our academic thoughts and discussions for some months and now it has finished we are in reflective mode. Much of what we have experienced throughout the pilot was striking and will give us food for thought for some time to come. For this entry, I am going to focus on an aspect that I had not really considered, or at least, not very much beyond the prosaic.

We knew before the pilot that prison and technology do not make comfortable bedfellows. Whilst on the outside, technology permeates virtually every aspect of our waking lives, the same cannot be said for those incarcerated. From the moment you step inside the prison gate, signs remind you of what you cannot bring into the carceral environment; top of the list are mobile phones, computers, USBs and recording devices. This meant that in very basic terms there could be no powerpoint, video clips or recordings of lectures. It also meant that we could not rely upon the internal learners having a shared knowledge of current affairs beyond that which was available in newspapers or on radio or television. All the above could be perceived as inadequacies and deprivations, however, we found a number of positives side-effects of these supposed failings.

In the university classroom, technology is commonplace; smartboards, computer lecterns, laptops, tablets and smartphones. All of this technology can enable learning on many levels, but can also provide irresistible diversion from the task at hand. Whilst the intention may be educational; for example taking notes on a laptop, the temptation to drift into social media, email and so can prove to be seductive. Conversely, the prison classroom contains little to attract attention, beyond some posters on the wall and the view from the windows which offered nothing of real interest. From the outset, and throughout the entire pilot, it appeared that the absence of technology heightened concentration. This was observable through increased eye-contact, body language and engagement with both academic discussions and general conversations across all learners. Furthermore, the absence of technological distraction impelled students to self-reliance in way (for the external learners, at least) they were largely unused to and generally unprepared for.

It should be acknowledged that this increase in engagement may also have been impacted by the strangeness of the prison environment (for the external students) and the anxiety involved in meeting new people (for all students). Nevertheless, engagement did not seem to decrease despite increasing familiarity with both the surroundings and participants.

All of the above is not to say that technology has no place in education; the ease of access to educational materials and the ability to engage in academic discourse globally demonstrate its power. What I would suggest it does is offer us all an opportunity to reflect upon our own use (and dare I say, reliance) upon technology as a replacement for deep learning.

Reflections from a Pilot

Firstly, I would like to apologise for the use of the first person. I have made an entire career of telling my students to use the third person. However, writing a blog is generally informal and a bit more personal.

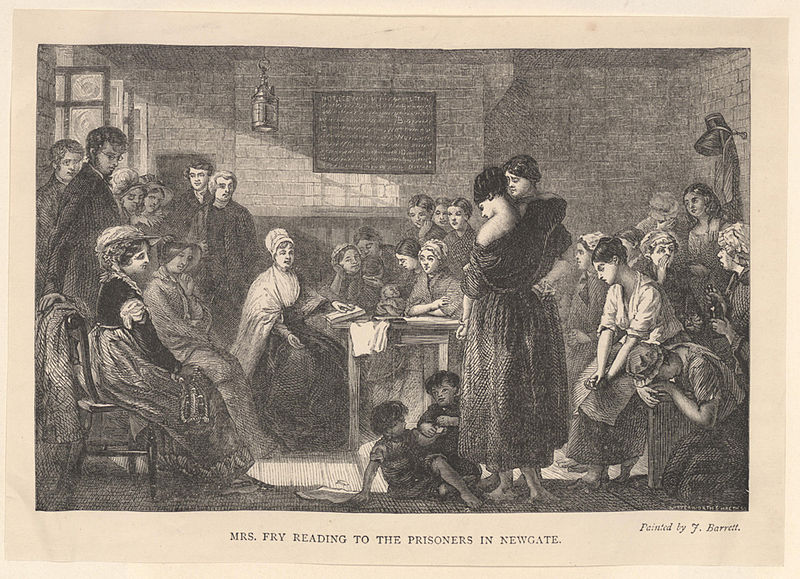

Throughout my years in academia there are a number of things I continue to find incredibly edifying; transferring research interests into teaching is one of them, even better when that is done outside of the traditional educational environment. The idea of education in prison is definitely not new, with roots in the old reformers (notably in the UK; Elizabeth Fry), with a clear focus on combating illiteracy. This was a product of penal policy that reflected a different social reality. In the 21st century, we have to re-imagine penal policy, alongside education, which can cater for the changed nature of our world.

Our recent pilot, was designed to explore some new approaches to education in both the prison and the university* . The idea was to bring university students and prisoners together and teach them the same topics encouraging them to engage with each other in discussions. This was envisaged as a process whereby all participants would be equal learners; leaving all other identities behind. The main thinking behind the approach taken was predicated on universal notions; the respect for humanity and the opportunity to express oneself uninhibited among equals. With this in mind, teaching in prisons should not be any different to teaching at University, provided that all learners feel safe and they are ready to engage. In the planning stages, my concerns were primarily on the way equality could be maintained. In addition, the levels of engagement and the material covered were also issues that created some trepidation. The knowledge that this pilot would be the blueprint for the design of a new level 6 module made the undertaking even more exciting.

The pilot involved 9 hours of teaching in prison with additional sessions before and after in order to familiarise all learners with each other, the environment and the learning process. Through the three teaching sessions, we all observed the transformative effect of education. From early suspicion and reluctance among learners to the confident elaboration of complex arguments. It took one simple statement to get the learning process going. This is when the pilot became a new lens through which I saw education, in prison with all my students, as a thriving learning environment.