Home » Refugees (Page 3)

Category Archives: Refugees

A Christmas blog

What is Christmas? A date in the calendar in winter towards the end of the year to celebrate one of the main religious festivals of the Christian calendar. The Romans replaced a pagan festival with the birth of the head of the, then new, religion. Since then as time progresses, more customs and traditions are added, to make this festival more packed with meaning and importance. The gift of the 20th century’s big corporations was the addition to the date, the red Santa Claus who travels the planet on his sledge from the North Pole in a single day, offering gifts to all the well-behaved kids. The birth of Christ is miles away from the Poles but somehow the story’s embellishment continues.

In schools, kids across the world will re-enact the nativity scene, a romantic version of the birth of Jesus, minus their flight to Egypt and the slaughter of the infants. The nativity, is for many, their first attempt at theatre and most educators’ worst nightmare, as they will have to include all children regardless of talent or interest to this production. The play consists mostly of male characters (usually baby Jesus is someone’s doll) except for one. That of the mother of Jesus. The virgin Mary is located centre stage, sitting quietly, the envy of all other parent’s that their kid was not cast in such a reverent role. In recent years, charlatans tried to add more female roles by feminising the Angels and even giving the Inn keeper a daughter or even a wife. In most cases it was the need of introducing more characters in the play. Most productions now include barn animals (cats and dogs included), reindeers, trees, villagers, stars and even a moon. All castable parts not necessarily with a talking part.

The show usually feels that it lasts longer than it does. The actors become nervous, some forget their lines, others remember different lines, the music is off key and the parents jostle to get to prime position in order to record this show, that very few will ever watch. The costumes will be coming apart almost right after the show and the props are just about holding on with a lot of tape and superglue. The play will signal the end of the school season carrying the joyful message from the carpark to the people’s homes. This tradition carries on regardless of religious sentiments and affiliations. People to commemorate the birth of a man that billions of people consider the head of their faith.

Nativity is symbolic but its meaning changes with the times, leaving me wondering what our nativity will be in the 21st century. Imagine a baby Jesus floating face down on torrential Aegean waters, a virgin Mary hoping that this will be the last client for the day on the makeshift brothel maybe today is the day she gets her passport back; Joseph a broken man, laying by the side of the street on a cardboard; the angel a wingless woman living alone in emergency accommodation, living in fear, the villagers stunned in fear and everyone carrying on . Not as festive as the school production but after all, people living for year in austerity, and a lockdown and post-referendum decisions make it difficult to be festive. Regardless of the darkness that we live in, the nativity has a more fundamental message: life happens irrespective of circumstances and nothing can stop the birth of a new-born.

Merry Christmas to all from the Criminology Team

“My Favourite Things”: Amy

My favourite TV show - This is hard! I love a box set and it depends on my mood but This Is Us for when I need a good cry and Travels With My Father or Idiot Abroad for laughs (combines my love of travel with belly laughs) My favourite place to go - Mum and dad's. Their home and gites at Cousserat (shameless plug) in South West France is the most peaceful place I've ever been. Waking up with a view of the vines, having breakfast with my parents, running for miles and not seeing another car, the beautiful boulangeries and lively night markets. I wish I could travel over more than I do My favourite city - Paris My favourite thing to do in my free time - CrossFit - functional fitness combining cardio, gymnastics and Olympic weightlifting elements. It's super addictive and has a real sense of community so it's my social life as well as my gym My favourite athlete/sports personality - Any of the CrossFit women but Tia-Clair Toomey is an absolutely phenomenal athlete. Her mindset, work ethic and determination is inspiring My favourite actor - Tom Hardy. Needs no further explanation My favourite author - I can't remember the last time I read fiction. We're probably talking about the Jane Austen period it's been that long. If we're talking academia then Vicky Canning. We think alike and she's lovely My favourite drink - Diet Coke but I quit for months at a time because it's addictive. I also love Caribbean Nocco and lemon and ginger tea My favourite food - If I could only eat one food for the rest of my life it would definitely be chicken My favourite place to eat - My own dining room but in terms of restaurants there's so much choice in Manchester I rarely eat in the same place twice! I like people who - help others I don’t like it when people - are racist My favourite book - Gendered Harm and Structural Violence in the British Asylum System by Victoria Canning. It's been my go to during my PhD My favourite book character - Jo from Little Women My favourite film - Bridesmaids My favourite poem - I don't know a single poem. Is that bad? I studied English Literature at Access and I don't recall what I read My favourite artist/band - Emmy the Great has a special place in my heart My favourite song - I can't answer this. It's like choosing your favourite child My favourite art - I was on site during the fieldwork phase of my PhD research at a womens' group for newly arrived migrants. There was one woman who didn't speak a word of English but she loved the art activities. She created a series of tiles over a few weeks. The artwork was beautiful because of what it symbolised. The woman came in withdrawn and closed, wearing her veil tightly like it was an extra layer of protecting from the world. By the time she completed her mosaic tiles she looked taller, younger and she smiled. Her veil loosened, as did her furrowed brow. It was absolutely incredible to see the change in her. Sat with a group of women making mosaic tiles for a few weeks positively influenced her wellbeing. My favourite person from history - I'm a woman from Manchester so it has to be Emmeline Pankhurst. Her legacy continues today in her home which is now home to a range of women's services

What’s in the future for criminology?

This year marks 20 years that we have been offering criminology at the University of Northampton and understandably it has made us reflect and consider the direction of the discipline. In general, criminology has always been a broad theoretical discipline that allows people to engage in various ways to talk about crime. Since the early days when Garofalo coined the term criminology (still open to debate!) there have been 106 years of different interpretations of the term.

Originally criminology focused on philosophical ideas around personal responsibility and free will. Western societies at the time were rapidly evolving into something new that unsettled its citizens. Urbanisation meant that people felt out of place in a society where industrialisation had made the pace of life fast and the demands even greater. These societies engaged in a relentless global competition that in the 20th century led into two wars. The biggest regret for criminology at the time, was/is that most criminologists did not identify the inherent criminality in war and the destruction they imbued, including genocide.

In the ashes of war in the 20th century, criminology became more aware that criminality goes beyond individual responsibility. Social movements identified that not all citizens are equal with half the population seeking suffrage and social rights. It was at the time the influence of sociology that challenged the legitimacy of justice and the importance of human rights. In pure criminological terms, a woman who throws a brick at a window for the sake of rights is a crime, but one that is arguably provoked by a society that legitimises inequality and exclusion. Under that gaze what can be regarded as the highest crime?

Criminologists do not always agree on the parameters of their discipline and there is not always consensus about the nature of the discipline itself. There are those who see criminology as a social science, looking at the bigger picture of crime and those who see it as a humanity, a looser collective of areas that explore crime in different guises. Neither of these perspectives are more important than the other, but they demonstrate the interesting position criminology rests in. The lack of rigidity allows for new areas of exploration to become part of it, like victimology did in the 1960s onwards, to the more scientific forensic and cyber types of criminology that emerged in the new millennium.

In the last 20 years at Northampton we have managed to take onboard these big, small, individual and collective responses to crime into the curriculum. Our reflections on the nature of criminology as balancing different perspectives providing a multi-disciplinary approach to answering (or attempting to, at least) what crime is and what criminology is all about. One thing for certain, criminology can reflect and expand on issues in a multiplicity of ways. For example, at the beginning of 21st terrorism emerged as a global crime following 9/11. This event prompted some of the current criminological debates.

So, what is the future of criminology? Current discourses are moving the discipline in new ways. The environment and the need for its protection has emerge as a new criminological direction. The movement of people and the criminalisation of refugees and other migrants is another. Trans rights is another civil rights issue to consider. There are also more and more calls for moving the debates more globally, away from a purely Westernised perspective. Deconstructing what is crime, by accommodating transnational ideas and including more colleagues from non-westernised criminological traditions, seem likely to be burning issues that we shall be discussing in the next decade. Whatever the future hold there is never a dull moment with criminology.

The Crime of Tourism

Every year millions of people will visit a number of countries for their summer vocations. European, American and Asian, mainly tourists will pack their bags and seek sea, sun and long beaches to relax, in a number of countries. In Greece for example, tourism is big business. The country’s history, natural beauty, large unspoiled countryside and of course, climate make it an ideal destination for those who wish to put some distance between the worries of work and their annual leave. There is something for everyone, for the culture seeker, to the sun lounger, to the all-inclusive resident. For the next however long you are on Greek time.

Last year the country was visited by approximately 30 million tourists, 3 million of whom come from the UK. This is not simply a pleasure trip; it is a multi-billion dollar industry, involving tour operators, airlines, hotels, catering, tour-guides, car rentals and so many more industries. They all try to acquire the tourist dollar in the pursuit of happiness; in Greece alone the tourist contributions last year came somewhere near to 14 billion euros and provide 17% of the country’s jobs.

In this context, tourism is a wonderful social activity that allows people from different cultures to come together, try new things and perspectives. Most importantly to get some tan, so people in the office know we were away, get some tacky t-shirts and a bottle of suspiciously strong local drink which tasted like ambrosia whilst on holiday. Some of us will learn to pronounce (badly) places we have never heard of, while others will

be reading questionable novels about romance, mystery or drama. Others will bag a romance, maybe a venereal disease, heartbreak (especially if the previous is confirmed) or even the love of their life. All these and many more will happen this summer and every summer since the wave of mass tourism began.

During this season and every season, countless people will prepare meals, clean rooms, and serve cold drinks on the sinking sand, paid minimum wage and rely heavily on the few tips left behind. The work hours are excruciatingly long, over 8 hours in the baking sun in some cases, without a hat, protection or even a break. If this was a mine it would have been the one I read about in Herodotus, where the Athenians were sent to as slaves. In the back of the house an army of trainee cooks, warehouse staff and cleaners will slave away without tips or recognition. In their ranks, there is a number of unrecorded migrants that work under exploitative conditions out of fear of deportation or worst.

In the midst of the worker’s exploitation we have the odd cultural clashes between tourists as to who gets the sun lounger closest to the pool and who can push pass the queue to get first to the place of interest you were told by someone in the office you must go to. Of course there are those who have famously complained before, because on their way to their exclusive resort were confronted by sad looking refugees. Not a real advertisement on tolerance and co-existence, quite the opposite. Of course, in this blog I have left completely out the carbon footprint we leave whenever we do these summer escapes, but that shall be the subject for another post.

Tourism is a great thing but when Eurostat claims that one in two Greeks cannot afford a weeks’ vacation in Greece, then something maybe wrong with the world. Holidays are great and we want the places to be clean, we want to travel in comfort and we want quality in what we will consume. I wonder if we have the same concerns about those people who enter Europe in shaky boats, the back of lorries or on foot, crossing borders without shoes.

Forgotten

It is now nearly two weeks since Remembrance Day and reading Paula’s blog. Whilst understanding and agreeing with much of the sentiment of the blog, I must confess I have been somewhat torn between the critical viewpoint presented and the narrative that we owe the very freedoms we enjoy to those that served in the second world war. When I say served, I don’t necessarily mean those just in the armed services, but all the people involved in the war effort. The reason for the war doesn’t need to be rehearsed here nor do the atrocities committed but it doesn’t hurt to reflect on the sacrifices made by those involved.

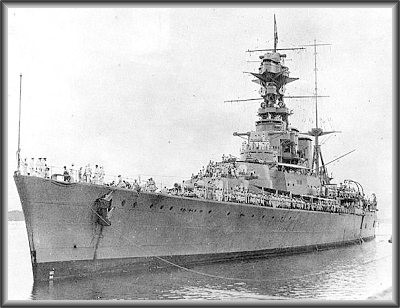

My grandad, now deceased, joined the Royal Navy as a 16-year-old in the early 1930s. It was a job and an opportunity to see the world, war was not something he thought about, little was he to know that a few years after that he would be at the forefront of the conflict. He rarely talked about the war, there were few if any good memories, only memories of carnage, fear, death and loss. He was posted as missing in action and found some 6 months later in hospital in Ireland, he’d been found floating around in the Irish Sea. I never did find out how this came about. He had feelings of guilt resultant of watching a ship he was supposed to have been on, go down with all hands, many of them his friends. Fate decreed that he was late for duty and had to embark on the next ship leaving port. He described the bitter cold of the Artic runs and the Kamikaze nightmare where planes suddenly dived indiscriminately onto ships, with devastating effect. He had half of his stomach removed because of injury which had a major impact on his health throughout the rest of his life. He once described to me how the whole thing was dehumanised, he was injured so of no use, until he was fit again. He was just a number, to be posted on one ship or another. He swerved on numerous ships throughout the war. He had medals, and even one for bravery, where he battled in a blazing engine room to pull out his shipmates. When he died I found the medals in the garden shed, no pride of place in the house, nothing glorious or romantic about war. And yet as he would say, he was one of the lucky ones.

My grandad and many like him are responsible for my resolution that I will always use my vote. I do this in the knowledge that the freedom to be able to continue to vote in any way I like was hard won. I’m not sure that my grandad really thought that he was fighting for any freedom, he was just part of the war effort to defeat the Nazis. But it is the idea that people made sacrifices in the war so that we could enjoy the freedoms that we have that is a somewhat romantic notion that I have held onto. Alongside this is the idea that the war effort and the sacrifices made set Britain aside, declaring that we would stand up for democracy, freedom and human rights.

But as I juxtapose these romantic notions against reality, I begin to wonder what the purpose of the conflict was. Instead of standing up for freedom and human rights, our ‘Great Britain’ is prepared to get into bed with and do business with the worst despots in the world. Happy to do business with China, even though they incarcerate up to a million people such as the Uygurs and other Muslims in so called ‘re-education camps’, bend over backwards to climb into bed with the United States of America even though the president is happy to espouse the shooting of unarmed migrating civilians and conveniently play down or ignore Saudi Arabia’s desolation of the Yemini people and murder of political opponents.

In the clamber to reinforce and maintain nationalistic interests and gain political advantage our government and many like it in the west have forgotten why the war time sacrifices were made. Remembrance should not just be about those that died or sacrificed so much, it should be a time to reflect on why.

Are we really free?

This year the American Society of Criminology conference (Theme: Institutions, Cultures and Crime) is in Atlanta, GA a city famous for a number of things; Mitchell’s novel, (1936), Gone with the Wind and the home of both Coca-Cola, and CNN. More importantly the city is the birthplace and sometime home of Dr Martin Luther King Jr and played a pivotal role in the Civil Rights Movement. Throughout the city there are reminders of King’s legacy, from street names to schools and of course, The King Center for Non-Violent Social Change.

This week @manosdaskalou and I visited the Center for Civil and Human Rights, opened in 2014 with the aim of connecting the American Civil Rights Movement, to broader global claims for Human Rights. A venue like this is an obvious draw for criminologists, keen to explore these issues from an international perspective. Furthermore, such museums engender debate and discussion around complex questions; such as what it means to be free; individually and collectively, can a country be described as free and why individuals and societies commit atrocities.

According to a large-scale map housed within the Center the world is divided up into countries which are free, partially free and not free. The USA, the UK and large swathes of what we would recognise as the western world are designated free. Other countries such as Turkey and Bolivia are classified as partially free, whilst Russia and Nigeria are not free. Poor Tonga receives no classification at all. This all looks very scientific and makes for a graphic illustration of areas of the world deemed problematic, but by who or what? There is no information explaining how different countries were categorised or the criteria upon which decisions were made. Even more striking in the next gallery is a verbatim quotation from Walter Cronkite (journalist, 1916-2009) which insists that ‘There is no such thing as a little freedom. Either you are all free, or you are not free.’ Unfortunately, these wise words do not appear to have been heeded when preparing the map.

Similarly, another gallery is divided into offenders and victims. In the first half is a police line-up containing a number of dictators, including Hitler, Pol Pot and Idi Amin suggesting that bad things can only happen in dictatorships. But what about genocide in Rwanda (just one example), where there is no obvious “bad guy” on which to pin blame? In the other half are interactive panels devoted to individuals chosen on the grounds of their characteristics (perceived or otherwise). By selecting characteristics such LGBT, female, migrant or refugee, visitors can read the narratives of individuals who have been subjected to such regimes. This idea is predicated on expanding human empathy, by reading these narratives we can understand that these people aren’t so different to us.

Museums such as the Center for Civil and Human Rights pose many more questions than they can answer. Their very presence demonstrates the importance of understanding these complex questions, whilst the displays and exhibits demonstrate a worldview, which visitors may or may not accept. More importantly, these provide a starting point, a nudge toward a dialogue which is empathetic and (potentially) focused toward social justice. As long as visitors recognise that nudge long after they have left the Center, taking the ideas and arguments further, through reading, thinking and discussion, there is much to be hopeful about.

In the words of Martin Luther King Jr (in his 1963, Letter from Birmingham Jail):

‘Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly’

Why Criminology terrifies me

Cards on the table; I love my discipline with a passion, but I also fear it. As with other social sciences, criminology has a rather dark past. As Wetzell (2000) makes clear in his book Inventing the Criminal: A History of German Criminology 1880-1945 the discipline has (perhaps inadvertently) provided the foundations for brutality and violence. In particular, the work of Cesare Lombroso was utilised by the Nazi regime because of his attempts to differentiate between the criminal and the non-criminal. Of course, Lombroso was not responsible (he died in 1909) and could not reasonably be expected to envisage the way in which his work would be used. Nevertheless, when taken in tandem with many of the criticisms thrown at Lombroso’s work over the past century or so, this experience sounds a cautionary note for all those who want to classify along the lines of good/evil. Of course, Criminology is inherently interested in criminals which makes this rather problematic on many grounds. Although, one of the earliest ideas students of Criminology are introduced to, is that crime is a social construction, which varies across time and place, this can often be forgotten in the excitement of empirical research.

My biggest fear as an academic involved in teaching has been graphically shown by events in the USA. The separation of children from their parents by border guards is heart-breaking to observe and read about. Furthermore, it reverberates uncomfortably with the historical narratives from the Nazi Holocaust. Some years ago, I visited Amsterdam’s Verzetsmuseum (The Resistance Museum), much of which has stayed with me. In particular, an observer had written of a child whose wheeled toy had upturned on the cobbled stones, an everyday occurrence for parents of young children. What was different and abhorrent in this case was a Nazi soldier shot that child dead. Of course, this is but one event, in Europe’s bloodbath from 1939-1945, but it, like many other accounts have stayed with me. Throughout my studies I have questioned what kind of person could do these things? Furthermore, this is what keeps me awake at night when it comes to teaching “apprentice” criminologists.

This fear can perhaps best be illustrated by a BBC video released this week. Entitled ‘We’re not bad guys’ this video shows American teenagers undertaking work experience with border control. The participants are articulate and enthusiastic; keen to get involved in the everyday practice of protecting what they see as theirs. It is clear that they see value in the work; not only in terms of monetary and individual success, but with a desire to provide a service to their government and fellow citizens. However, where is the individual thought? Which one of them is asking; “is this the right thing to do”? Furthermore; “is there another way of resolving these issues”? After all, many within the Hitler Youth could say the same.

For this reason alone, social justice, human rights and empathy are essential for any criminologist whether academic or practice based. Without considering these three values, all of us run the risk of doing harm. Criminology must be critical, it should never accept the status quo and should always question everything. We must bear in mind Lee’s insistence that ‘You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view. Until you climb inside of his skin and walk around in it’ (1960/2006: 36). Until we place ourselves in the shoes of those separated from their families, the Grenfell survivors , the Windrush generation and everyone else suffering untold distress we cannot even begin to understand Criminology.

Furthermore, criminologists can do no worse than to revist their childhood and Kipling’s Just So Stories:

I keep six honest serving-men

(They taught me all I knew);

Their names are What and Why and When

And How and Where and Who (1912: 83)

Bibliography

Browning, Christopher, (1992), Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland, (London: Penguin Books)

Kipling, Rudyard, (1912), Just So Stories, (New York: Doubleday Page and Company)

Lee, Harper, (1960/2006), To Kill a Mockingbird, (London: Arrow Books)

Lombroso, Cesare, (1911a), Crime, Its Causes and Remedies, tr. from the Italian by Henry P. Horton, (Boston: Little Brown and Co.)

-, (1911b), Criminal Man: According to the Classification of Cesare Lombroso, Briefly Summarised by His Daughter Gina Lombroso Ferrero, (London: G. P. Putnam’s Sons)

-, (1876/1878/1884/1889/1896-7/ 2006), Criminal Man, tr. from the Italian by Mary Gibson and Nicole Hahn Rafter, (London: Duke University Press)

Solway, Richard A., (1982), ‘Counting the Degenerates: The Statistics of Race Deterioration in Edwardian England,’ Journal of Contemporary History, 17, 1: 137-64

Wetzell, Richard F., (2000), Inventing the Criminal: A History of German Criminology 1880-1945, (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press)