Home » Pandemic

Category Archives: Pandemic

25 years of Criminology

When the world was bracing for a technological winter thanks to the “millennium bug” the University of Northampton was setting up a degree in Criminology. Twenty-five years later and we are reflecting on a quarter of a century. Since then, there have been changes in the discipline, socio-economic changes and wider changes in education and academia.

The world at the beginning of the 21st century in the Western hemisphere was a hopeful one. There were financial targets that indicated a raising level of income at the time and a general feeling of a new golden age. This, of course, was just before a new international chapter with the “war on terror”. Whilst the US and its allies declared the “war on terror” decreeing the “axis of evil”, in Criminology we offered the module “Transnational Crime” talking about the challenges of international justice and victor’s law.

Early in the 21st century it became apparent that individual rights would take centre stage. The political establishment in the UK was leaving behind discussions on class and class struggles and instead focusing on the way people self-identify. This ideological process meant that more Western hemisphere countries started to introduce legal and social mechanisms of equality. In 2004 the UK voted for civil partnerships and in Criminology we were discussing group rights and the criminalisation of otherness in “Outsiders”.

During that time there was a burgeoning of academic and disciplinary reflection on the way people relate to different identities. This started out as a wider debate on uniqueness and social identities. Criminology’s first cousin Sociology has long focused on matters of race and gender in social discourse and of course, Criminology has long explored these social constructions in relation to crime, victimisation and social precipitation. As a way of exploring race and gender and age we offered modules such as “Crime: Perspectives of Race and Gender” and “Youth, Crime and the Media”. Since then we have embraced Kimberlé Crenshaw’s concept of intersectionality and embarked on a long journey for Criminology to adopt the term and explore crime trends through an increasingly intersectional lens. Increasingly our modules have included an intersectional perspective, allowing students to consider identities more widely.

The world’s confidence fell apart when in 2008 in the US and the UK financial institutions like banks and other financial companies started collapsing. The boom years were replaced by the bust of the international markets, bringing upheaval, instability and a lot of uncertainty. Austerity became an issue that concerned the world of Criminology. In previous times of financial uncertainty crime spiked and there was an expectation that this will be the same once again. Colleagues like Stephen Box in the past explored the correlation of unemployment to crime. A view that has been contested since. Despite the statistical information about declining crime trends, colleagues like Justin Kotzé question the validity of such decline. Such debates demonstrate the importance of research methods, data and critical analysis as keys to formulating and contextualising a discipline like Criminology. The development of “Applied Criminological Research” and “Doing Research in Criminology” became modular vehicles for those studying Criminology to make the most of it.

During the recession, the reduction of social services and social support, including financial aid to economically vulnerable groups began “to bite”! Criminological discourse started conceptualising the lack of social support as a mechanism for understanding institutional and structural violence. In Criminology modules we started exploring this and other forms of violence. Increasingly we turned our focus to understanding institutional violence and our students began to explore very different forms of criminality which previously they may not have considered. Violence as a mechanism of oppression became part of our curriculum adding to the way Criminology explores social conditions as a driver for criminality and victimisation.

While the world was watching the unfolding of the “Arab Spring” in 2011, people started questioning the way we see and read and interpret news stories. Round about that time in Criminology we wanted to break the “myths on crime” and explore the way we tell crime stories. This is when we introduced “True Crimes and Other Fictions”, as a way of allowing students and staff to explore current affairs through a criminological lens.

Obviously, the way that the uprising in the Arab world took charge made the entire planet participants, whether active or passive, with everyone experiencing a global “bystander effect”. From the comfort of our homes, we observed regimes coming to an end, communities being torn apart and waves of refugees fleeing. These issues made our team to reflect further on the need to address these social conditions. Increasingly, modules became aware of the social commentary which provides up-to-date examples as mechanism for exploring Criminology.

In 2019 announcements began to filter, originally from China, about a new virus that forced people to stay home. A few months later and the entire planet went into lockdown. As the world went into isolation the Criminology team was making plans of virtual delivery and trying to find ways to allow students to conduct research online. The pandemic rendered visible the substantial inequalities present in our everyday lives, in a way that had not been seen before. It also made staff and students reflect upon their own vulnerabilities and the need to create online communities. The dissertation and placement modules also forced us to think about research outside the classroom and more importantly outside the box!

More recently, wars in Europe, the Middle East, Africa and Asia have brought to the forefront many long posed questions about peace and the state of international community. The divides between different geopolitical camps brought back memories of conflicts from the 20th century. Noting that the language used is so old, but continues to evoke familiar divisions of the past, bringing them into the future. In Criminology we continue to explore the skills required to re-imagine the world and to consider how the discipline is going to shape our understanding about crime.

It is interesting to reflect that 25 years ago the world was terrified about technology. A quarter of a century later, the world, whilst embracing the internet, is worriedly debating the emergence of AI, the ethics of using information and the difference between knowledge and communication exchanges. Social media have shifted the focus on traditional news outlets, and increasingly “fake news” is becoming a concern. Criminology as a discipline, has also changed and matured. More focus on intersectional criminological perspectives, race, gender, sexuality mean that cultural differences and social transitions are still significant perspectives in the discipline. Criminology is also exploring new challenges and social concerns that are currently emerging around people’s movements, the future of institutions and the nature of society in a global world.

Whatever the direction taken, Criminology still shines a light on complex social issues and helps to promote very important discussions that are really needed. I can be simply celebratory and raise a glass in celebration of the 25 years and in anticipation of the next 25, but I am going to be more creative and say…

To our students, you are part of a discipline that has a lot to say about the world; to our alumni you are an integral part of the history of this journey. To those who will be joining us in the future, be prepared to explore some interesting content and go on an academic journey that will challenge your perceptions and perspectives. Radical Criminology as a concept emerged post-civil rights movements at the second part of the 20th century. People in the Western hemisphere were embracing social movements trying to challenge the established views and change the world. This is when Criminology went through its adolescence and entered adulthood, setting a tone that is both clear and distinct in the Social Sciences. The embrace of being a critical friend to these institutions sitting on crime and justice, law and order has increasingly become fractious with established institutions of oppression (think of appeals to defund the police and prison abolition, both staples within criminological discourse. The rigour of the discipline has not ceased since, and these radical thoughts have led the way to new forms of critical Criminology which still permeate the disciplinary appeal. In recent discourse we have been talking about radicalisation (which despite what the media may have you believe, can often be a positive impetus for change), so here’s to 25 more years of radical criminological thinking! As a discipline, Criminology is becoming incredibly important in setting the ethical and professional boundaries of the future. And don’t forget in Criminology everyone is welcome!

SUPREME COURT VISIT WITH MY CRIMINOLOGY SQUAD!

Author: Dr Paul Famosaya

This week, I’m excited to share my recent visit to the Supreme Court in London – a place that never fails to inspire me with its magnificent architecture and rich legal heritage. On Wednesday, I accompanied our final year criminology students along with my colleagues Jes, Liam, and our department head, Manos, on what proved to be a fascinating educational visit. For those unfamiliar with its role, the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom stands at the apex of our legal system. It was established in 2009, and serves as the final court for all civil cases in the UK and criminal cases from England, Wales, and Northern Ireland. From a criminological perspective, this institution is particularly significant as it shapes the interpretation and application of criminal law through precedent-setting judgments that influence every level of our criminal justice system

7:45 AM: Made it to campus just in the nick of time to join the team. Nothing starts a Supreme Court visit quite like a dash through Abington’s morning traffic!

8:00 AM: Our coach is set to whisk us away to London!

Okay, real talk – whoever designed these coach air conditioning systems clearly has a vendetta against warm-blooded academics like me! 🥶 Here I am, all excited about the visit, and the temperature is giving me an impromptu lesson in ‘cry’ogenics. But hey, nothing can hold us down!.

Picture: Inside the coach where you can spot the perfect mix of university life – some students chatting about the visit, while others are already practising their courtroom napping skills 😴

There’s our department Head of Departmen Manos, diligently doing probably his fifth headcount 😂. Big boss is channelling his inner primary school teacher right now, armed with his attendance sheet and pen and all. And yes, there’s someone there in row 5 I think, who’s already dozed off 🤦🏽♀️ Honestly, can’t blame them, it’s criminally early!

9:05 AM The dreaded M1 traffic

Sometimes these slow moments give us the best opportunities to reflect. While we’re crawling through, my mind wanders to some of the landmark cases we’ll be discussing today. The Supreme Court’s role in shaping our most complex moral and legal debates is fascinating – take the assisted dying cases for instance. These aren’t just legal arguments; they’re profound questions about human dignity, autonomy, and the limits of state intervention in deeply personal decisions. It’s also interesting to think about how the evolution of our highest court reflects (or sometimes doesn’t reflect) the society it serves. When we discuss access to justice in our criminology lectures, we often talk about how diverse perspectives and lived experiences shape legal interpretation and decision-making. These thoughts feel particularly relevant as we approach the very institution where these crucial decisions are made.

The traffic might be testing our patience, but at least it’s giving us time to really think about these issues.

10:07 AM – Arriving London – The stark reality of London’s inequality hits you right here, just steps from Hyde Park.

Honestly, this is a scene that perfectly summarises the deep social divisions in our society – luxury cars pulling up to the Dorchester where rooms cost more per night than many people earn in a month, while just meters away, our fellow citizens are forced to make their beds on cold pavements. As a criminologist, these scenes raise critical questions about structural violence and social harms. When we discuss crime and justice in our lectures, we often talk about root causes. Here they are, laid bare on London’s streets – the direct consequences of austerity policies, inadequate mental health support, and a housing crisis that continues to push more people into precarity. But as we say in the Nigerian dictionary of life lessons – WE MOVE!! 🚀

10:31 AM Supreme Court security check time

Security check time, and LISTEN to how they’re checking our students’ water bottles! The way they’re examining those drinks is giving: Nah this looks suspicious 🤔

So there I am, breezing through security like a pro (years of academic conferences finally paying off!). Our students follow suit, all very professional and courtroom-ready. But wait for it… who’s that getting the extra-special security attention? None other than our beloved department head Manos! 😂

The security guard’s face is priceless as he looks through his bags back and forth. Jes whispers to me ‘is Manos trying to sneak in something into the supreme court?’ 😂 Maybe they mistook his collection of snacks for contraband? Or perhaps his stack of risk assessment forms looked suspicious? 😂 There he is, explaining himself, while the rest of us try (and fail) to suppress our giggles. He is a free man after all.

10: 44AM Right so first stop, – Court Room 1.

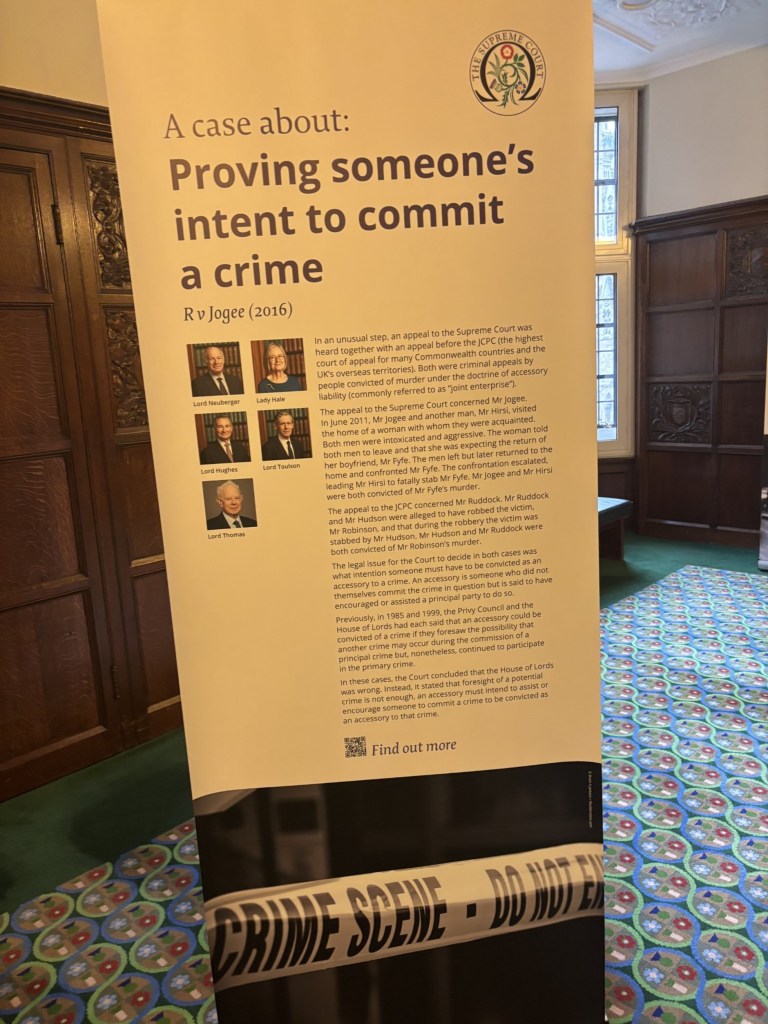

Our tour guide provided an overview of this institution, established in 2009 when it took over from the House of Lords as the UK’s highest court. The transformation from being part of the legislature to becoming a physically separate supreme court marked a crucial step in the separation of powers in the country’s legislation. There’s something powerful about standing in this room where the Justices (though they usually sit in panels of 5 or 7) make decisions. Each case mentioned had our criminology students leaning in closer, seeing how theoretical concepts from their modules materialise in this very room.

10:59 AM Moving into Court 2, the more modern one!

After exploring Courtroom 1, we moved into Court Room 2, and yep, I also saw the contrast! And apparently, our guide revealed, this is the judges’ favourite spot to dispense justice – can’t blame them, the leather chairs felt lush tbh!

Speaking of judges, give it up for our very own Joseph Buswell who absolutely nailed it when the guide asked about Supreme Court proceedings! 👏🏾 As he correctly pointed out, while we have 12 Supreme Court Justices in total, they don’t all pile in for every case. Instead, they work in panels of 3 or 5 (always keeping it odd to avoid those awkward tie situations). 👏🏾 And what makes Court Room 2 particularly significant for public access to justice the cameras and modern AV equipment which allow for those constitutional and legal debates to be broadcast to the nation. Spot that sneaky camera right at the top? Transparency level: 100% I guess!

The exhibition area

The exhibition space was packed with rich historical moments from the Supreme Court’s journey. Among the displays, I found myself pausing at the wall of Justice portraits. Let’s just say it offered quite the visual commentary on our judiciary’s journey towards representation…

Beyond the portraits, the exhibition showcased crucial stories of landmark judgments that have shaped our legal landscape. Each case display reminded us how crucial diverse perspectives are in the interpretation and application of law in our multicultural society.

11: 21AM Moving into Court 3, home of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC)

The sight of those Commonwealth flags tells a powerful story about the evolution of colonial legal systems and modern voluntary jurisdiction. Our guide explained how the JCPC continues to serve as the highest court of appeal for various independent Commonwealth countries. The relationship between local courts in these jurisdictions and the JCPC raises critical questions about legal sovereignty and judicial independence and the students were particularly intrigued by how different legal systems interact within this framework – with each country maintaining its own laws and legal traditions, yet looks to London for final decisions.

Breaktime!!!!

While the group headed out in search of food, Jes and I were bringing up the rear, catching up after the holiday and literally SCREAMING about last year’s Winter Wonderland burger and hot dog prices (“£7.50 for entry too? In this Keir Starmer economy?!😱”). Anyway, half our students had scattered – some in search of sustenance, others answering the siren call of Zara (because obviously, a Supreme Court visit requires a side of retail therapy 😉).

But here’s the moment that had us STUNNED – right there on the street, who should come power-walking past but Sir Chris Whitty himself! 😱 England’s Chief Medical Officer was on a mission, absolutely zooming past us like he had an urgent SAGE meeting to get to 🏃♂️. That man moves with PURPOSE! I barely had time to nudge Jes before he’d disappeared. One second he was there, the next – gone! Clearly, those years of walking to press briefings during the pandemic have given him some serious speed-walking skills! 👀

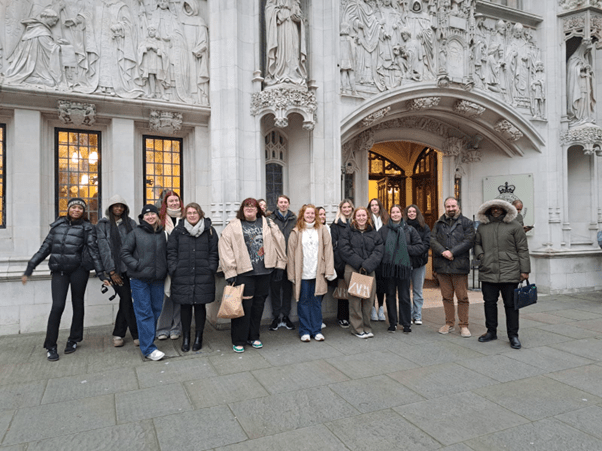

3:30 PM – Group Photo!

Looking at these final year criminology students in our group photo though! Even with that criminal early morning start (pun intended 😅), they made it through the whole Supreme Court experience! Big shout out to all of them 👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾 Can you spot me? I’m the one on the far right looking like I’m ready for Arctic exploration (as Paula mentioned yesterday), not London weather! 🥶 Listen, my ancestral thermometer was not calibrated for this kind cold today o! Had to wrap up in my hoodie like I was jollof rice in banana leaves – and you know we don’t play with our jollof! 😤

4:55 PM Heading Back To NN

On the journey back to NN, while some students dozed off (can’t blame them – legal learning is exhausting!), I found myself reflecting on everything we’d learned. From the workings of the highest court in our land to the stark realities of social inequality we witnessed near Hyde Park, today brought our theoretical classroom discussions into sharp focus. Sitting here, watching London fade into the distance, I’m reminded of why these field trips are so crucial for our students’ understanding of justice, law, and society.

Listen, can we take a moment to appreciate our driver though?! Navigating that M1 traffic like a BOSS, and getting us back safe and sound! The real MVP of the day! 👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾

And just like that, our Supreme Court trip comes to an end. From early morning rush to security check shenanigans, from spotting Chief Medical Officer on the streets to freezing our way through legal history – what a DAY!

To my amazing final years who made this trip extra special – y’all really showed why you’re the future of criminology! 👏🏾 Special shoutout to Manos (who can finally put down his attendance sheet 😂), Jes, and Liam for being the dream team! And to London… boyyyy, next time PLEASE turn up the heat! 🥶

As we all head our separate ways, some students were still chatting about the cases we learned about (while others were already dreaming about their beds 😴), In all, I can’t help but smile – because days like these? This is what university life is all about!

Until our next adventure… your frozen but fulfilled criminology lecturer, signing off! 🙌

Uncertainties…

Sallek Yaks Musa

Who could have imagined that, after finishing in the top three, James Cleverly – a frontrunner with considerable support – would be eliminated from the Conservative Party’s leadership race? Or that a global pandemic would emerge, profoundly impacting the course of human history? Indeed, one constant in our ever-changing world is the element of uncertainty.

Image credit: Getty images

The COVID-19 pandemic, which emerged in late 2019, serves as a stark reminder of our world’s interconnectedness and the fragility of its systems. When the virus first appeared, few could have foreseen its devastating global impact. In a matter of months, it had spread across continents, paralyzing economies, overwhelming healthcare systems, and transforming daily life for billions. The following 18 months were marked by unprecedented global disruption. Lockdowns, travel restrictions, and social distancing became the new norms, forcing us to rethink how we live, work, and interact.

The economic fallout was equally staggering. Supply chains crumbled, unemployment surged, and entire industries teetered on the brink of collapse. Education was upended as schools and universities hastily shifted online, exposing the limitations of existing digital infrastructure. Yet, amid the chaos, communities displayed remarkable resilience and adaptability, demonstrating the need for flexibility in the face of uncertainty.

Beyond health crises, the ongoing climate and environmental emergencies continue to fuel global instability. Floods, droughts, erratic weather patterns, and hurricanes such as Helene and Milton not only disrupt daily life but also serve as reminders that, despite advances in meteorology, no amount of preparedness can fully shield us from the overwhelming forces of nature.

For millions, however, uncertainty isn’t just a concept; it’s a constant reality. The freedom to choose, the right to live peacefully, and the ability to build a future are luxuries for those living under the perpetual threat of violence and conflict. Whether in the Middle East, Ukraine, or regions of Africa, where state and non-state actors perpetuate violence, people are forced to live day by day, confronted with life-threatening uncertainties.

On a more optimistic note, some argue that uncertainty fosters innovation, creativity, and opportunity. However, for those facing existential crises, innovation is a distant luxury. While uncertainty may present opportunities for some, for others, it can be a path to destruction. Life often leaves little room for choice, but when faced with uncertainty, we must make decisions – some minor, others, life-altering. Nonetheless, I am encouraged that while we may not control the future, we must navigate it as best we can, and lead our lives with the thought and awareness that, no one knows tomorrow.

2024: the year for community and kindness?

The year 2023 was full of pain, loss, suffering, hatred and harm. When looking locally, homelessness and poverty remain very much part of the social fabric in England and Wales, when looking globally, genocide, terror attacks and dictatorships are evident. Politics appear to have lost what little, if any, composure and respect it had: and all in all, the year leaves a somewhat bitter taste in the mouth.

Nevertheless, 2023 was also full of joy, happiness, hope and love. New lives have been welcomed into the world, achievements made, milestones met, communities standing together to march for a ceasefire and to protest against genocide, war, animal rights, global warming and violence against women to name but a few. It is this collective identity I hope punches its way into 2024, because I fear as time moves forward this strength in community, this sense of belonging, appears to be slowly peeling away.

When I recollect my grandparents and parents talking about ‘back in the day’ what stands out most to me is the community identity: the banding together during hard times. The taking an interest, providing a shoulder should it be required. Today, and even if I think back critically over the pandemic, the narrative is very singular: you must stay inside. You must be accountable, you must be responsible, you must get by and manage. There is no narrative of leaning on your neighbours, leaning on your community to the extent that, I’m under the impression, existed before. We have seen and felt this shift very much so within the sphere of criminal justice: it is the individual’s responsibility for their actions, their circumstances and their ‘lot in life’. And the Criminologists amongst you will be uttering expletives at this point. I think what I am attempting to get at, is that for 2024 I would like to see a shared identity as humankind come front and central. For inclusivity, kindness and hope to take flight and not because it benefits us as singular entities, but because it fosters our shared sense of, and commitment to, community.

But ‘community’ exists in so much more than just actions, it is also about our thoughts and beliefs. My worry: whilst kindness and support exist in the world, is that these features only exist if it does not disadvantage (or be perceived to disadvantage) the individual. An example: a person asks me for a sanitary product, and having many of them on me the vast majority of the time, means I am able and happy to accommodate. But what if I only had one left and the likelihood of me needing the last one is pretty high? Do I put myself at a later disadvantage for this person? This person is a stranger: for a friend I wouldn’t even think, I would give it to them. I know I would, and have given out my last sanitary product to strangers who have asked on a number of occasions. And if everyone did this, then once I need a product I can have faith that someone else will be able to support me when required. The issue, in this convoluted way of getting there, is for most of us (including me as evidenced) there is an initial reaction to centralise ‘us’ as an individual rather than focus on the community aspect of it. How will, or even could, this impact me?

Now, I appreciate this is overly generalised, and for those that foster community to all (not just those in their community and are generally very selfless) I apologise. But in 2024, I would like to see people, myself included, act and believe in this sense of community rather than the individualised self. I want people to belong, to support and to generally be kind and not through thinking about how it impacts them to do so. We do not have to be friends with everyone, but just a general level of kindness, understanding and a shared want for a better, inclusive, and safe future would be great!

So Happy New Year to everyone! I hope our 2024 is full of peace, prosperity, community, safety and kindness!

Pregnancy and Lavender Fields

If being a women means that you will experience harm due to your socially constructed sex/gender, being pregnant and a mother certainly adds to this. The rose-tinted view of pregnancy implies that pregnancy is the most wonderful of experiences. There is imagery of the most privileged of mothers with their pregnancy ‘glow’, in fields of [insert flower here] holding their bumps with the largest of smiles. Outside of smiles and lavender field imagery, judgment is reserved for pregnant women who do not enjoy pregnancy. In a world of ‘equality gone mad’, it seems that whilst some pregnant women may have a variety of hurdles to face, it is presumed that they should carry on living in the exact same way as those who are not pregnant.

Maybe you lose your job upon becoming pregnant and your workplace does not provide you with sick pay when needed. Maybe it is harder for you to access healthcare and screenings due to racism and xenophobia. Perhaps it is a Covid-19 pandemic, your boss is a bit disgruntled that you are pregnant and despite the legal guidance stating that pregnant people should isolate you are told that you need to work anyway. Or perhaps you are quite ill during your pregnancy, you must try to cope and continue to work regardless, but must also hide this sickness from your customers and colleagues. Whilst at the same time it is unlikely that there are places for you to rest or be sick/ill in peace. If any time is taken off work you may then be considered as being work-shy by some. Despite it being well documented that some pregnancy related ill-health conditions, like hyperemesis, have serious consequences, such as the termination of pregnancy, death and mothers taking their own lives (with or without suitable interventions).

Before labour, if you go to the triage room screaming in pain, maybe you will need to wait some time at the reception for staff to assist you, and perhaps you may be asked to ‘be quiet’ so as to not disturb the equilibrium of the waiting room. Maybe your labour is incredibly painful but apparently you must ‘take it like a champ’ and pain relief medication may be withheld. Maybe you will receive a hefty bill from the NHS for their services due to your undocumented migrant status, refused asylum application or have no recourse to public funds. If experiencing pain post-labour, maybe your pain is disregarded, and you face life-threatening consequences due to this.

Once you become a mother maybe you are more exhausted than your partner, maybe your partner is a abusive, maybe they cannot push a pram, change nappies, calm a crying baby because of toxic masculinity. If your baby becomes upset (as they do sometimes) whilst out and about you may need a quite low sensory place to feed them, or for them to relax but there is nowhere suitable to go. If looking flustered or a bit dishevelled whilst out maybe you are treated as a shop-lifting suspect by security and shop assistants.

If you have the privilege of being able to return to work, ensure that you return within the optimum time frame as having too much or too little time off work is not viewed as desirable. Also, make sure you have some more babies but not too many as both would be deemed selfish. Whether you breastfeed or provide formula both options are apparently wrong, in different ways. If you do breastfeed and need to use a breast pump whilst returning to work you may find that there are no/or a limited amount of suitable rooms available on public transport, at transport hubs, in public venues and workplaces for using a breast pump. This, among with other factors, such as the state of the economy, the lack of/a poor amount of maternity pay, and childcare costs, make the ability to both maintain formal employment and be present as a healthy mother difficult. Notably, the differences, extent and severity of harmful experiences differ depending on power, your status and identity attributes, if your gender does not neatly fit into the white privileged/women/female/mother box you will face further challenges.

It seems that society, its institutions and people want babies to be produced but do not want to deal with the realities that come with pregnancy and motherhood.

Here to serve but not your slave

My wife and I were fortunate enough to go on holiday this year to a beautiful island in the Caribbean. Palm Island, a stone’s throw, well 10-minute boat ride (I’m not prone to exaggeration you understand) from Union Island, and some 45 minutes by plane to Barbados is a unique paradise described as the Maldives in the Caribbean.

The circumstances of the people that work on Palm Island (and history) are perhaps not too dissimilar to those that work in Cape Verde, a subject of a previous blog. Wages are poor, the staff are not exactly affluent, and work is hard to come by. Many have gravitated to Palm Island from nearby islands to find work and have subsequently stayed on Union Island, commuting every day after a long shift. Others stay on Palm Island in staff accommodation, returning home to their families every few months in St. Vincent and elsewhere. Whilst guests enjoy luxurious accommodation, great food and plentiful drinks, the workers receiving low wages, relying on a percentage of the service charge and tips, do not even have the luxury of a constant water supply on Union Island. Palm Island has its own water processing plant, Union Island does not. Hence the gardener telling me he had to pay $250 dollars to have water delivered to his home; £100 for the water and $150 for the delivery. The dry season is hard going and financially precarious.

The Island shut down during Covid and many of the workers returned home with no wages for the duration. Poverty is not an alien concept to them. Their lives and that of the visitors couldn’t be further apart and yet are intertwined by capitalism in the form of tourism. They need the tourists to sustain the jobs, the more tourists, the more in service charges and tips. Of course, the owners of the island want more tourists because it brings in more revenue. A moral dilemma for some perhaps, well for me anyway. I won’t be pretentious and state that I go to the island to support the local economy, vis-a-vie the poor people, I go there for a really good holiday. But here is the crux of the matter, and hence the title, I try my utmost to treat the staff with respect. I recognise that they are paid to serve me and other guests, and they do a brilliant job, but they are not my servants or slaves (the historical significance should be obvious). And yet I have witnessed people demanding drinks without a please or thank you, “give me a vodka”, “she wants a rum and coke”. I have seen people coming off yachts with day passes for the island, they came, they saw, they made a complete mess and they left…. You can clear up our mess! Glasses left all over the beach, beach towels left wherever, they last used them. “What did your last servant die of”, I ask, as they slope off into the rum filled sunset? “It certainly wasn’t old age” I shout after them. But it just seems lost on them.

I ask myself would they have treated me like that had I been the one behind the bar? I think not, perhaps the lighter colour of my skin may have persuaded them that I am worthy of some courtesy. But then who knows, it seems that some people that have money have a certain arrogance and disregard for anyone else.

Not all of the customers were like that, most were polite and some very friendly with the staff. But we shouldn’t forget the power dynamics, and above all else the privilege that some of us enjoy. Above all else it is a useful reminder that when people are there to serve, they are not your servant nor your slave and they and the job they do deserves respect.

The decline of social interaction

I am writing about the decline of social interaction today – not because of my interest in sociological interactionist perspectives but because of the declining state of social interactions and the general lack of engagement in societies lately. Additionally, as we come to the end of Mental Health Awareness Week, it is important to reflect on the relationship between social interaction and mental health.

Previously, I have written about the students’ lack of engagement in classrooms and their unwillingness to participate and commit to their studies. In that blog, I tried to understand why students are becoming increasingly disinterested in their studies and why attendance has plummeted. I identified some interconnected issues that might be causing these problems, including anxiety, financial difficulties, lack of sense of belonging and the difficulties of readjusting to life after the pandemic. Furthermore, I have also tried to proffer some solutions for how I think students can resolve these challenges and detailed the importance of being part of a community. However, upon reflection, I realised that I might have underestimated the impact of social interactions in societies today.

First, I’d like to define social interactions as a meaning-making process. It is a process through which individuals exchange ideas, relate, manage information, and react to each other’s dealings. Of course, social interaction encompasses communication but constitutes characteristics like mannerisms, gesticulations, eye contact, smiling, slang, etc. Blumer (1969) lays bare the fundamental premise of this approach (and for the sociologists reading, I recognise the work of Mead, so don’t worry) by exploring some basic premises through which interactions form human character. While these characteristics are more appreciated physically, even though they may be passive sometimes, they create a different feel and richness for socialisation, relationships, and interaction. Not only that, they all constitute the genetic makeup of our social behaviour which invariably translates to our social character. However, in recent times, the nuances that we enjoy being physically engaged with one another seem to be slowly disappearing. Our digital presence, emoticons, Gifs, stickers and memes have replaced many of these characteristics and nuances.

It is important to note, though, that being among people, participating in discussions physically and forming peer relationships all provide us with a good recipe through which we can use to improve our psychological well-being, social interactions and skills. Take a ride on the underground trains in London during peak periods, for example, and you will hear how loud the silence is despite the crowded setting.

I believe that we are living in a time when people are becoming more and more disconnected from one another, and part of the problem also has to do with the consequences of the pandemic social distancing/quarantine rules – which was a necessary evil.

While the social distancing guidance may have been withdrawn, I think there seems to be a continuous trend where people keep each other’s distance even after the pandemic. Loneliness is becoming more perverse; people are becoming removed from social life, and procrastination seems to have taken centre stage.

Again, the rise and usage of multiple social media platforms have also put us where we are slowly replacing our physical presence with our digital presence. We can easily sit behind our WhatsApp, Twitter or TikTok for hours without speaking – but submerged in this digital world. While I am not in any way condemning the use of social media, I think we risk our physical interactions being replaced with digital interactions, which I also consider a contributing factor to the decline of social interactions we face today.

I agree that we all must move with time; we have to adjust ourselves to this new world, or else we will be left behind. However, I suggest not letting our physical engagement dissipate, nor should we allow our digital presence to become more important than our in-person presence. As indicated earlier, we are witnessing a decline in social interactions, but the task ahead of us as a society is to begin to consider ways to ameliorate this problem. There is value in social interaction, even if some might not see the benefits of it. Some studies in the past have found that ensuring good social interactions can improve psychological well-being. Thus, my assignment for everyone reading this blog today is to pick up your phone and check up on a loved one! The sun is out (well, for now); take a break and go out with your friends, have some food and drinks over the weekend, exchange some jokes, and smile!

Life, indeed, is a beautiful thing to have.

Reference

Blumer, H. (1969). Symbolic interactionism: Perspective and methods. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

When This is Over: Reflections on an Unequal Pandemic

This week a book was released which I both co-edited and contributed to and which has been two years in the making. When This is Over: Reflections on an Unequal Pandemic is a volume combining a range of accounts from artists to poets, practitioners to academics. Our initial aim of the book was borne out of a need for commemoration but we cannot begin to address this without considering inequalities throughout the pandemic.

Each of the four editors had both personal and professional reasons for starting the project. I – like many – was (and still is) deeply affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. When we first went into lockdown, we were shown the data every day, telling us the numbers of people who had the virus and of those who had died with COVID-19. Behind these numbers, I saw each and every person. I thought about their loved ones left behind, how many of them died alone without being able to say goodbye other than through a video screen. I thought about what happened to the bodies afterwards, how death rites would be impacted and how the bereaved would cope without hugs and face to face social support. Then my grandmother died. She had overcome COVID-19 in the way that she was testing negative. But I heard her lungs on the day she died. I know. And so, I became even more consumed with questions of the COVID-19 dead, with/of debates. I was angry at the narratives surrounding the disposability of people’s lives, at people telling me ‘she had a good innings’. It was personal now.

I now understood the impact of not being able to hug my grandpa at my grandmother’s funeral, and how ‘normal’ cultural practices surrounding death were disturbed. My grandmother loved singing in choirs and one of the traumatic parts of our bereavement was not being able to sing at her funeral as she would have wanted and how we wanted to remember her. Lucy Easthope, a disaster planner and one of my co-authors speaks of her frustrations in this regard:

“we’ve done something incredibly traumatising to the families that is potentially bigger than the bereavement itself. In any disaster you should still allow people to see the dead. It is a gross inhumanity of bad planning that people couldn’t’t visit the sick, view the deceased’s bodies, or attend funerals. Had we had a more liberal PPE stockpile we could have done this. PPE is about accessing your loved ones and dead ones, it is not just about medical professionals.”

The book is divided into five parts, each addressing a different theme all of which I argue are relevant to criminologists and each part including personal, professional, and artistic reflections of the themes. Part 1 considered racialised, classed, and gendered identities which impacted on inequality throughout the pandemic, asking if we really are in this together? In this section former children’s laureate Michael Rosen draws from his experience of having COVID-19 and being hospitalised in intensive care for 48 days. He writes about disposability and eugenics-style narratives of herd immunity, highlighting the contrast between such discourse and the way he was treated in the NHS: with great care and like any other patient.

The second part of the book considers how already existing inequalities have been intensified throughout the pandemic in policing, law and immigration. Our very own @paulsquaredd contributed a chapter on the policing of protests during the pandemic, drawing on race in the Black Lives Matter protests and gender in relation to Sarah Everard. As my colleagues and students might expect, I wrote about the treatment of asylum seekers during the initial lockdown periods with a focus on the shift from secure and safe self-contained housing to accommodating people seeking safety in hotels.

Part three considers what happens to the dead in a pandemic and draws heavily on the experiences of crematoria and funerary workers and how they cared for the dead in such difficult circumstances. This part of the book sheds light on some of the forgotten essential workers during the pandemic. During lockdown, we clapped for NHS workers, empathised with supermarket workers and applauded other visible workers but there were many less visible people doing valuable unseen work such as caring for the dead. When it comes to death society often thinks of those who cared for them when they were alive and the bereaved who were left to the exclusion of those who look after the body. The section provides some insight into these experiences.

Moving through the journey of life and death in a pandemic, the fourth section focusses on questions of commemoration, a process which is both personal and political. At the heart of commemorating the COVID-19 dead in the UK is the National COVID Memorial Wall, situated facing parliament and sat below St Thomas’ hospital. In a poignant and political physical space, the unofficial wall cared for by bereaved family members such as Fran Hall recognises and remembers the COVID dead. If you haven’t visited the wall yet, there will be a candlelit vigil walk next Wednesday, 29th March at 7pm and those readers who live further afield can digitally walk the wall here, listening to the stories of bereaved family members as you navigate the 150,837 painted hearts.

The final part of the book both reflects on the mistakes made and looks forward to what comes next. Can we do better in the next pandemic? Emergency planner Matt Hogan presents a critical view on the handling of the pandemic, returning to the refrain, ‘emergency planning is dead. Long live emergency planning’. Lucy Easthope is equally critical, developing what she has discussed in her book When the Dust Settles to consider how and what lessons we can learn from the management of the pandemic. Lucy calls out for activism, concluding with calls to ‘Give them hell’ and ‘to shout a little louder’.

Concluding in his afterword, Gary Younge suggests this is ‘teachable moment’, but will we learn?

When This is Over: Reflections on an Unequal Pandemic is published by Policy Press, an imprint of Bristol University Press. The book can be purchased directly from the publisher who offer a 25% discount when subscribing. It can also be purchased from all good book shops and Amazon.

World Mental Health Day 2022

Monday marked World Mental Health day, that one day of the year when corporations and establishments which act like corporations tell us how much mental health matters to them, how their worker’s wellbeing matters to them. Given many sectors are affected by industrial action, or balloting for industrial action, this seems like a contradiction. Could it be possible that these industries and government are causing mental ill health, while paying lip service as a PR tool? Could it be that capitalism and inequalities associated with it are both the cause of mental health conditions and the very thing that prevents recovery from it?

Capitalism, I argue, is the root of a lot of society’s problems. The climate crisis is largely caused by consumerism and our innate need for stuff. The cost of living crisis is more like a greed crisis, since the rich are getting richer and the corporations are making phenomenal profits while small business struggle to make ends meet and what used to be the middle class are relying on food banks, getting second jobs and wondering whether they can afford to put the heating on. No wonder swathes of us are suffering with anxiety, depression and other mental health conditions. Of course, I cannot argue that capitalism is to blame for all manner of mental health conditions as that is simply not the case. There are many causes of mental health conditions which simply cannot be blamed on the environment. The mental health conditions I discuss here are the depression and anxiety that so many of us suffer as a result of environmental stressors, namely capitalist embedded society.

The mental health epidemic did not start with the current ‘crises’[1] though. Yes, the COVID-19 pandemic contributes and exacerbates already existing inequalities and the UK saw an increase in adults reporting psychological distress during the first two years of the pandemic, yet fewer were being diagnosed, perhaps due to inaccessibility of GPs during this time. Even before all these things which have exacerbated mental health conditions, prevalence of common mental disorders has been increasing since the 1990s. At the same time, we have seen in the UK, neoliberal ideology and austerity politics privatise parts of the NHS and decimate funding to services which support those with needs relating to their mental health.

I am not a psychologist but I know a problem when I see or experience one. Several months ago, I was feeling a bit low and anxious so I sought help from the local NHS talking therapies service. The service was still in restrictions and I was offered a series of six DBT-based telephone appointments. After the first appointment, I realised that this was not going to help. It was suggested to have a structure in my life. I have a job, doctoral studies, dog, home educated teenager, and I go to the gym. Scheduling and structure was already an essential part of my life. Next, I was taught coping skills. ‘Get some exercise’, ‘go for a walk’. Ditto previous session – I’m gym obsessed, with a dog I walk every day, mostly in green spaces. My coping skills were not the problem either. What I realised was that I didn’t need psychological help, I needed my environment to change. I needed my workload to be reduced, my PhD to finally end, my teenage daughter not to have any teenage problems, my dog to behave, for someone to pay my mortgage off, and a DIY fairy to fix the house I don’t have time to fix. No amount of therapy could ever change these things. I realised that it wasn’t me that was the problem – it was the world around me.

I am not alone. The Mental Health Foundation have published some disturbing statistics:

- In the past year, 74% of people (in a YouGov survey of 4,619) have felt so stressed they have been overwhelmed or unable to cope.

- Of those who reported feeling stressed in the past year, 22% cited debt as a stressor.

- Housing worries are a key source of stress for younger people (32% of 18-24-year-olds cited it as a source of stress in the past year). This is less so for older people (22% for 45-54-year-olds and just 7% for over 55s).

The data show not only the magnitude of the problem, but they also indicate some of the prevalent stressors in these respondents’ lives. Over 1 in 5 people cited debt as a stressor, and this survey was undertaken long before the cost of greed crisis. It is deeply concerning, particularly considering the anticipated increase in interest rates and the cost of energy bills at the moment.

The survey also showed that young people are concerned about housing, and this will have a disproportionate impact on care leavers who may not have family to support them and working class young people who cannot afford housing.

The causes of both these issues are predominantly fat cat employers who can afford to pay sufficient and fair wages, fat cat landlords buying up property in droves to rent them out at a huge profit, not to mention the fat cat energy suppliers making billions when half the country is now in fuel poverty. All the while, our capitalism loving government plays the game, shorting the pound to raise profits for their pals while the rest of us struggle to pay our mortgages after the Bank of England raised interest rates. No wonder we’re so stressed!

For work-related stress, anxiety and depression, the Labour Force Survey finds levels at the highest in this century, with 822,000 suffering from such mental health conditions. The Health and Safety Executive show that education and human, health and social work are the industries with the highest prevalence of stress, anxiety and depression. It is yet another symptom of neoliberalism which applies corporate values to education and public services, where students are the cash cow, and workers are exploited; and health and social work being under funded for years. Is it any wonder then that both nurses and lecturers are balloting for industrial action right now?

Despite all this, when World Mental Health Day arrives, it becomes the perfect PR exercise to pay lip service to staff wellbeing. The rail industry are in a period of industrial action, yet I have seen posts on rail companies’ social media promoting World Mental Health Day. Does the promotion of mental health initiatives include fair pay and conditions for staff? I think not.

Something needs to give, but what?

As a union member and representative, I argue for the need for employers to pay staff appropriately for the work they do, and to treat them fairly. This would at least address work and finance related stressors. Sanah Ahsan argues for a universal basic income, for safe and affordable housing and for radical change in the structural inequalities in the UK. Perhaps we could start with addressing structural inequalities. Gender, race and class all impact on mental health, with women more likely to be diagnosed with depression, Black women at an increased risk of common mental health disorders and the poor all more likely to suffer mental health conditions yet less likely to receive adequate and culturally appropriate support. In my research with women seeking asylum, there is a high prevalence of PTSD, yet therapy is difficult to access, in part due to language difficulties but also due to cultural differences. Structural inequalities then not only contribute to harm to marginalised people’s mental health, but also form a barrier to support.

I do not have a realistic solution, but I have the feeling society needs a radical social change. We need an end to structural inequalities, and we need to ensure those most impacted by inequalities get adequate and appropriate support. When I look to see who is in charge, and who could be in charge if the tides were to turn, and I don’t see this happening anytime soon.

[1] I’m hesitant to call them crises. As Canning (2017:9) explains in relation to the refugee ‘crisis’, a crisis is unforesessable and unavoidable. The climate crisis has been foreseen for decades, and the cost of living crisis is avoidable if you compare other European countries such as France where the impact has been mitigated by the government. The mental health crisis has also been growing for a long time and the extent to which we say today could be both foreseen and avoided.

Criminology First Week Activity (2021)

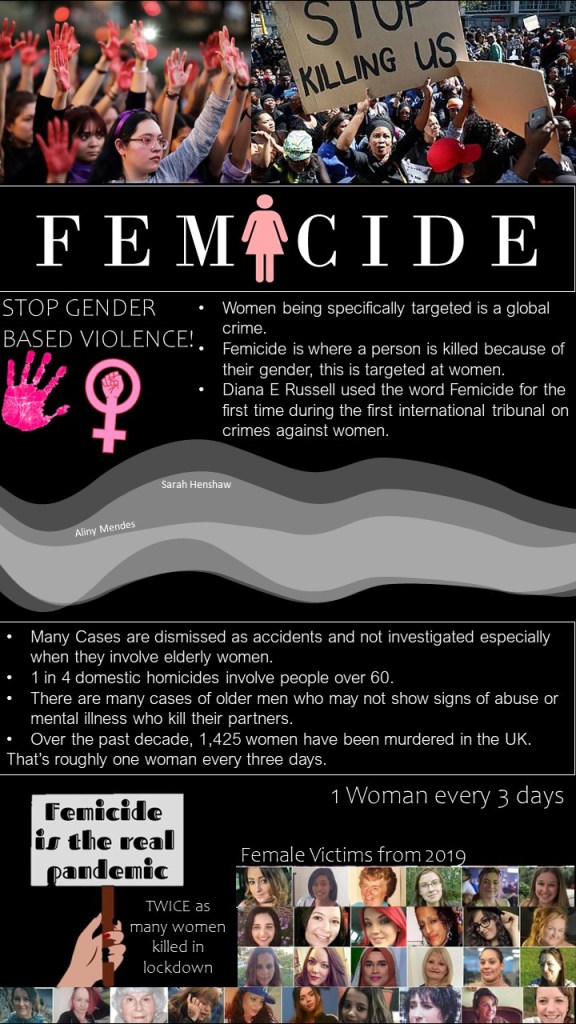

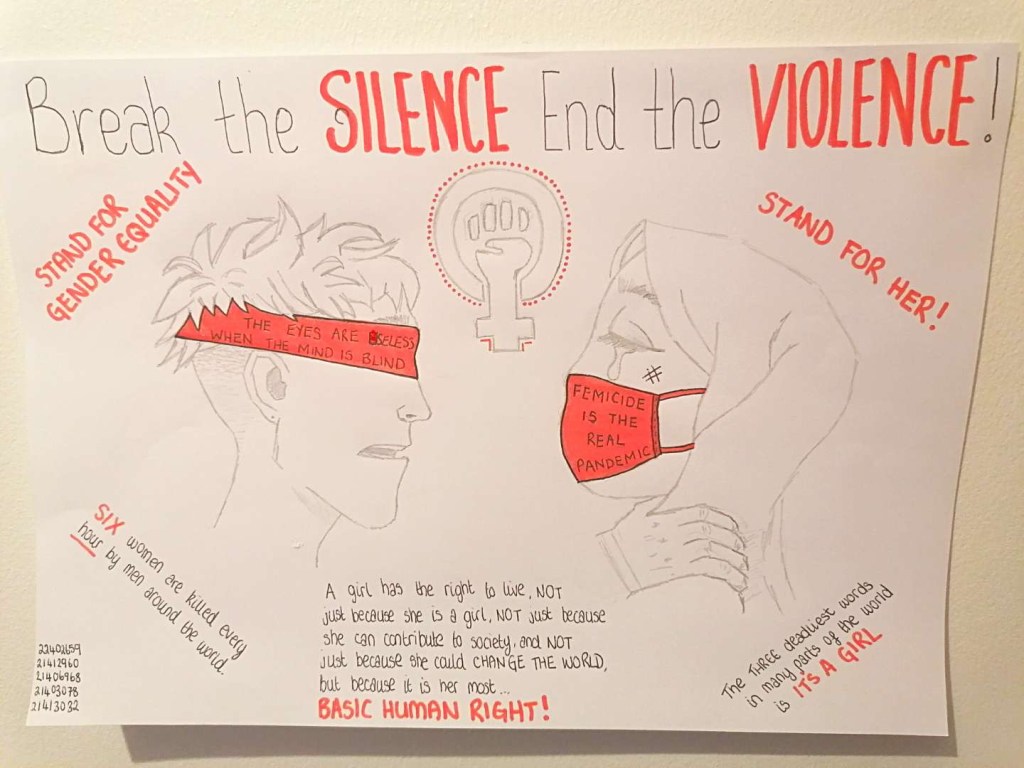

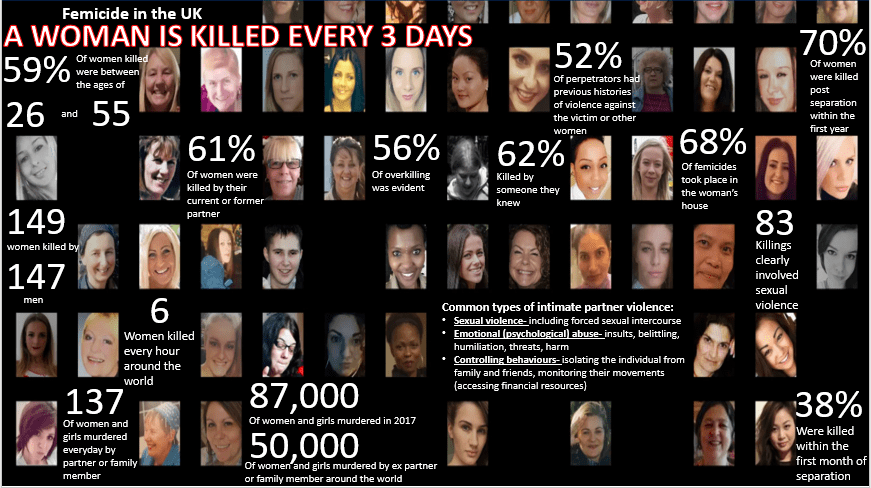

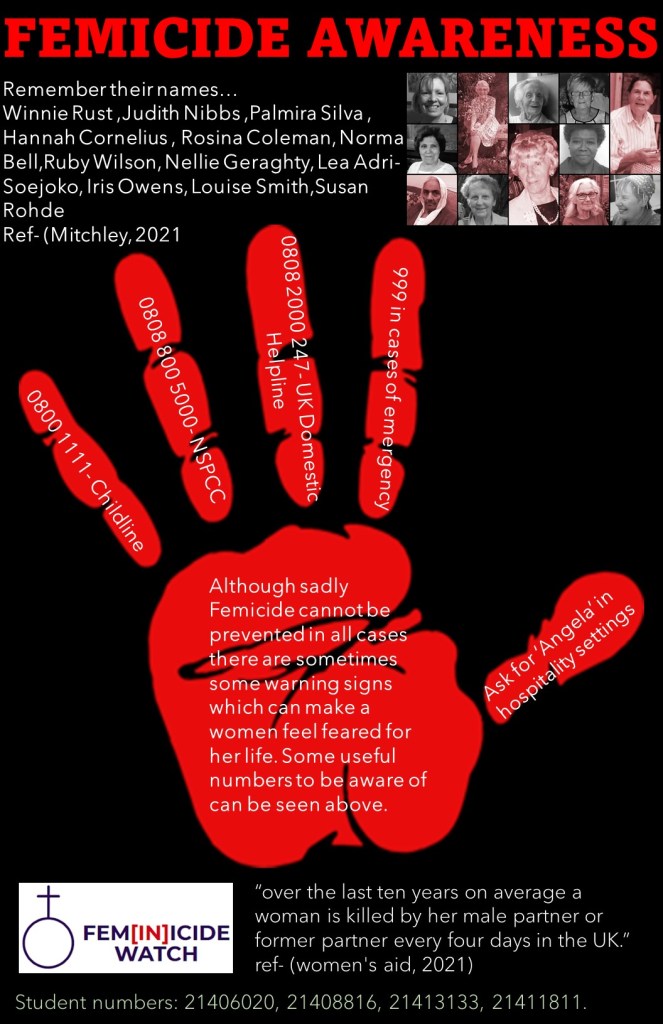

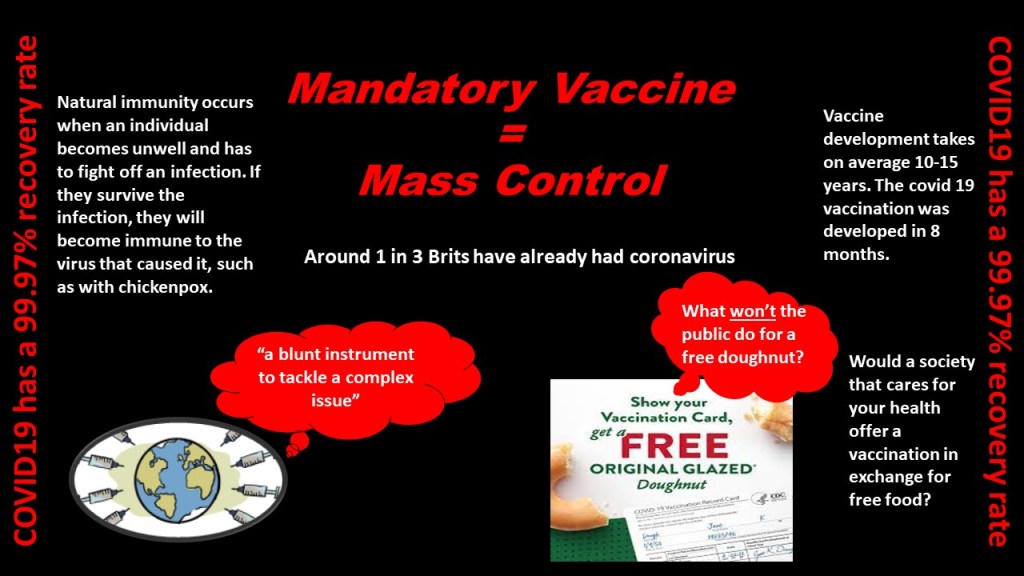

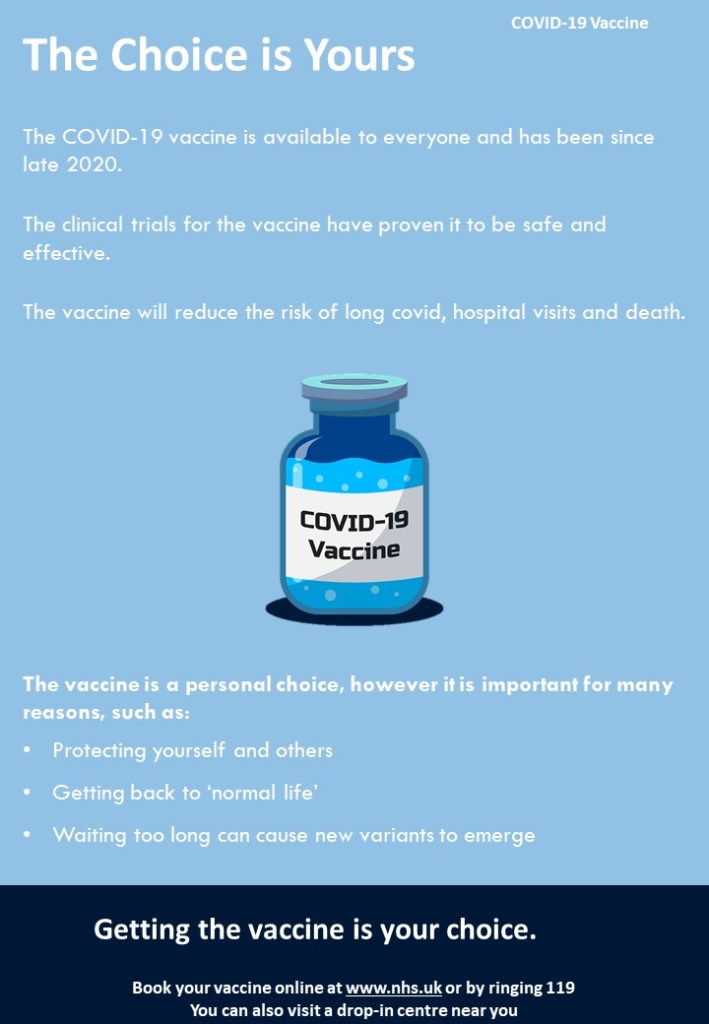

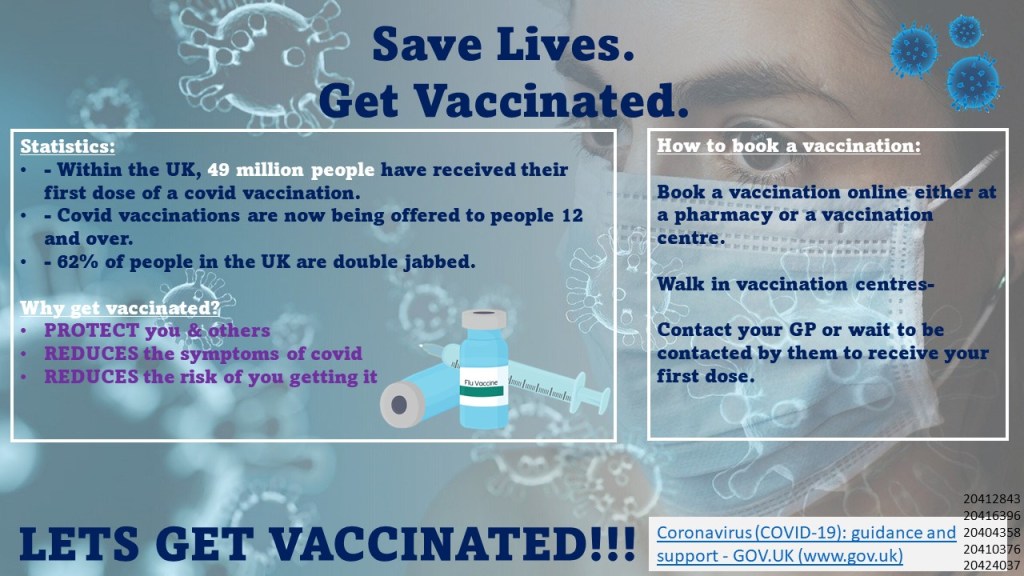

Before embarking on a new academic year, it is always worth reflecting on previous years. In 2020, the first year we ran this activity, it was a response to the challenges raised by the Covid-19 pandemic and was designed to serve two different aims. The first of these, was of course, academic, we wanted students to engage with a activity designed to explore real social problems through visual criminology, inspiring the criminological imagination for the year ahead. Second, we were operating in an environment that nobody was prepared for: online classes, limited physical contact, mask wearing, hand sanitising, socially distanced. All of these made it very difficult for staff and students to meet and to build professional relationships. The team needed to find a way for people to work together safely, within the constraints of the Covid legislation of the time and begin to build meaningful relationships with each other.

The start of the 2021/2022 academic year had its own pandemic challenges with many people still shielding, others awaiting covid vaccinations and the sheer uncertainty of going out and meeting people under threat of a deadly disease. After taking on board student feedback, we decided to run a similar activity during the first week of the new term. As before, students were placed into small groups, advised to take the default approach of online meetings (unless all members were happy to meet physically), provided with a very short prompt and limited guidance as to how best to tackle the project. The prompts were as follows:

Year 1: Femicide

Year 2: Mandatory covid vaccinations

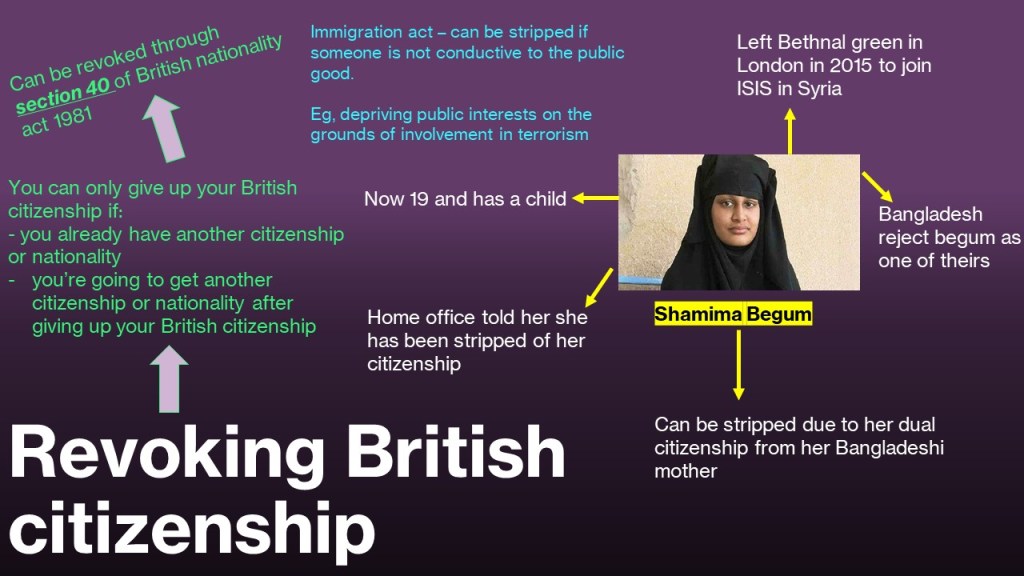

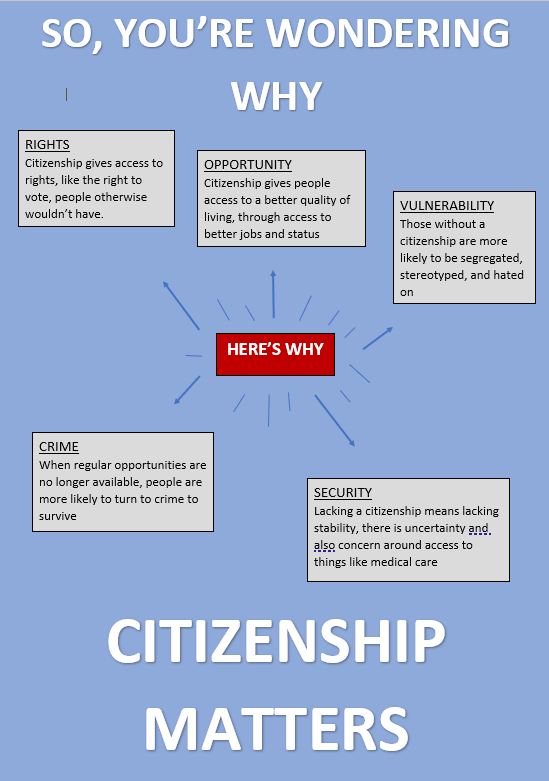

Year 3: Revoking British citizenship

Many of the students had never physically met, yet managed to come together in the midst of a pandemic, negotiate a strategy, carry out the work and produce well designed and thoughtful, criminological posters.

As can be seen from the collage below, everyone involved embraced the challenge and created some remarkable posters. Some of these have been shared previously across social media but this is the first time they have all appeared together in one place.

I am sure everyone will agree our students demonstrated knowledge, understanding, resilience and stamina. We will be running a similar activity for the first week of the academic year 2022-2022, with different prompts to provoke thought and encourage dialogue and team work. We’ll also take on board student and staff feedback from the previous two activities. Plato once wrote that ‘our need will be the real creator’, put more colloquially, necessity is the mother of all invention, and that is certainly true of our first week activity.

Who knows what exciting ideas and posters will be demonstrated this time, but one thing is for sure Criminology students have the opportunity to flex their activism, prepare to campaign for social justice, in the process becoming real #Changemakers.