Home » Lectures (Page 2)

Category Archives: Lectures

Things I Miss (and don’t) – 5teveh

I was chatting with my wife the other day about household finances in the current situation. My wife has lost her two zero hours contract jobs (I’m not sure why they call it a contract when basically it’s a one-way thing; you work when we want you to and if you don’t agree then you don’t work) and adjustments have to be made. I’m not moaning about our finances, just stating a fact, things have to change. Anyway, my wife declares that whilst she enjoys visiting coffee shops it’s not something she particularly misses. A bit ironic really as we can’t go out for coffee anyway in the current countrywide shutdown. Of course, not going out for coffee saves money. The conversation got me thinking about what I miss, and conversely what I don’t in these unusual circumstances.

In a previous conversation, a friend and colleague said he missed the chats over coffee that we’d have on a weekly basis. I too miss this, but it wasn’t just the chats but also the venue, where we were able to somehow hide ourselves in our own little sanctuary, away from what at times felt like the madness of the daily machinations of campus life.

I never thought I’d say this, but I miss the classes, lectures, seminars, workshops, call them what you will. I miss the interaction with the students and that spark that sometimes occurs when you know they’ve got it, they comprehend what it is you are saying. I don’t miss the frustration felt when students for what ever reason just can’t or won’t engage. I don’t miss travelling into work in all the traffic. At least my fuel bill has gone down, and the environment is benefitting.

I miss seeing my boys, I get to speak to them or text them all the time but its not quite the same. They are grown men now but, they are still my boys. I miss being able to see my mum, she’s getting on a bit now. Sometimes I thought it a bit of a chore having to visit her, a duty to be carried out, but now… well its hard, despite speaking to her everyday on the phone.

I miss being able to pop out with my wife to various antique shops and auction rooms in pursuit of my hobby. I’m repairing an old clock now and need some parts. Ebay is useful but its not quite the same as sourcing them elsewhere.

I miss going out to meet my best mate for a beer and a Ruby (calling it a curry just isn’t cool). We’ve been friends for over forty years now and perhaps only meet up every three or four months. We text and chat but its not quite the same.

But what I miss most of all, is freedom. Freedom to see who I like and when I like. Freedom to visit where I like and to chat to whom I like, whether that be in a coffee shop with the owner or another customer or at an auction with other bidders and onlookers. It’s funny isn’t it, we take our freedom for granted until it is taken away from us. All those things that we moan about, all the problems that we see, real or imagined, pale into insignificance against a loss of freedom.

Come Together

For much of the year, the campus is busy. Full of people, movement and voice. But now, it is quiet… the term is over, the marking almost complete and students and staff are taking much needed breaks. After next week’s graduations, it will be even quieter. For those still working and/or studying, the campus is a very different place.

This time of year is traditionally a time of reflection. Weighing up what went well, what could have gone better and what was a disaster. This year is no different, although the move to a new campus understandably features heavily. Some of the reflection is personal, some professional, some academic and in many ways, it is difficult to differentiate between the three. After all, each aspect is an intrinsic part of my identity.

Over the year I have met lots of new people, both inside and outside the university. I have spent many hours in classrooms discussing all sorts of different criminological ideas, social problems and potential solutions, trying always to keep an open mind, to encourage academic discourse and avoid closing down conversation. I have spent hour upon hour reading student submissions, thinking how best to write feedback in a way that makes sense to the reader, that is critical, constructive and encouraging, but couched in such a way that the recipient is not left crushed. I listened to individuals talking about their personal and academic worries, concerns and challenges. In addition, I have spent days dealing with suspected academic misconduct and disciplinary hearings.

In all of these different activities I constantly attempt to allow space for everyone’s view to be heard, always with a focus on the individual, their dignity, human rights and social justice. After more than a decade in academia (and even more decades on earth!) it is clear to me that as humans we don’t make life easy for ourselves or others. The intense individual and societal challenges many of us face on an ongoing basis are too often brushed aside as unimportant or irrelevant. In this way, profound issues such as mental and/or physical ill health, social deprivation, racism, misogyny, disablism, homophobia, ageism and many others, are simply swept aside, as inconsequential, to the matters at hand.

Despite long standing attempts by politicians, the media and other commentators to present these serious and damaging challenges as individual failings, it is evident that structural and institutional forces are at play. When social problems are continually presented as poor management and failure on the part of individuals, blame soon follows and people turn on each other. Here’s some examples:

Q. “You can’t get a job?”

A “You must be lazy?”

Q. “You’ve got a job but can’t afford to feed your family?

A. “You must be a poor parent who wastes money”

Q. “You’ve been excluded from school?”

A. “You need to learn how to behave?”

Q. “You can’t find a job or housing since you came out of prison?”

A. “You should have thought of that before you did the crime”

Each of these questions and answers sees individuals as the problem. There is no acknowledgement that in twenty-first century Britain, there is clear evidence that even those with jobs may struggle to pay their rent and feed their families. That those who are looking for work may struggle with the forces of racism, sexism, disablism and so on. That the reasons for criminality are complex and multi-faceted, but it is much easier to parrot the line “you’ve done the crime, now do the time” than try and resolve them.

This entry has been rather rambling, but my concluding thought is, if we want to make better society for all, then we have to work together on these immense social problems. Rather than focus on blame, time to focus on collective solutions.

Am I a criminologist? Are you a criminologist?

I’m regularly described as a criminologist, but more loathe to self-identify as such. My job title makes clear that I have a connection to the discipline of criminology, yet is that enough? Can any Tom, Dick or Harry (or Tabalah, Damilola or Harriet) present themselves as a criminologist, or do you need something “official” to carry the title? Is it possible, as Knepper suggests, for people to fall into criminology, to become ‘accidental criminologists’ (2007: 169). Can you be a criminologist without working in a university? Do you need to have qualifications that state criminology, and if so, how many do you need (for the record, I currently only have 1 which bears that descriptor)? Is it enough to engage in thinking about crime, or do you need practical experience? The historical antecedents of theoretical criminology indicate that it might not be necessary, whilst the existence of Convict Criminology suggests that experiential knowledge might prove advantageous….

Does it matter where you get your information about crimes, criminals and criminal justice from? For example, the news (written/electronic), magazines, novels, academic texts, lectures/seminars, government/NGO reports, true crime books, radio/podcasts, television/film, music and poetry can all focus on crime, but can we describe this diversity of media as criminology? What about personal experience; as an offender, victim or criminal justice practitioner? Furthermore, how much media (or experience) do you need to have consumed before you emerge from your chrysalis as a fully formed criminologist?

Could it be that you need to join a club or mix with other interested persons? Which brings another question; what do you call a group of criminologists? Could it be a ‘murder’ (like crows), or ‘sleuth’ (like bears), or a ‘shrewdness’ (like apes) or a ‘gang’ (like elks)? (For more interesting collective nouns, see here). Organisations such as the British, European and the American Criminology Societies indicate that there is a desire (if not, tradition) for collectivity within the discipline. A desire to meet with others to discuss crime, criminality and criminal justice forms the basis of these societies, demonstrated by (the publication of journals and) conferences; local, national and international. But what makes these gatherings different from people gathering to discuss crime at the bus stop or in the pub? Certainly, it is suggested that criminology offers a rendezvous, providing the umbrella under which all disciplines meet to discuss crime (cf. Young, 2003, Lea, 2016).

Is it how you think about crime and the views you espouse? Having been subjected to many impromptu lectures from friends, family and strangers (who became aware of my professional identity), not to mention, many heated debates with my colleagues and peers, it seems unlikely. A look at this blog and that of the BSC, not to mention academic journals and books demonstrate regular discordance amongst those deemed criminologists. Whilst there are commonalities of thought, there is also a great deal of dissonance in discussions around crime. Therefore, it seems unlikely that a group of criminologists will be able to provide any kind of consensus around crime, criminality and criminal justice.

Mannheim proposed that criminologists should engage in ‘dangerous thoughts’ (1965: 428). For Young, such thinking goes ‘beyond the immediate and the pragmatic’ (2003: 98). Instead, ‘dangerous thoughts’ enable the linking of ‘crime and penality to the deep structure of society’ (Young, 2003: 98). This concept of thinking dangerously and by default, not being afraid to think differently, offers an insight into what a criminologist might do.

I don’t have answers, only questions, but perhaps it is that uncertainty which provides the defining feature of a criminologist…

References:

Knepper Paul, (2007), Criminology and Social Policy, (London: Sage)

Lea, John, (2016), ‘Left Realism: A Radical Criminology for the Current Crisis’, International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy, 5, 3: 53-65

Mannheim, Hermann, (1965), Comparative Criminology: A Textbook: Volume 2, (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul)

Young, Jock, (2003), ‘In Praise of Dangerous Thoughts,’ Punishment and Society, 5, 1: 97-107

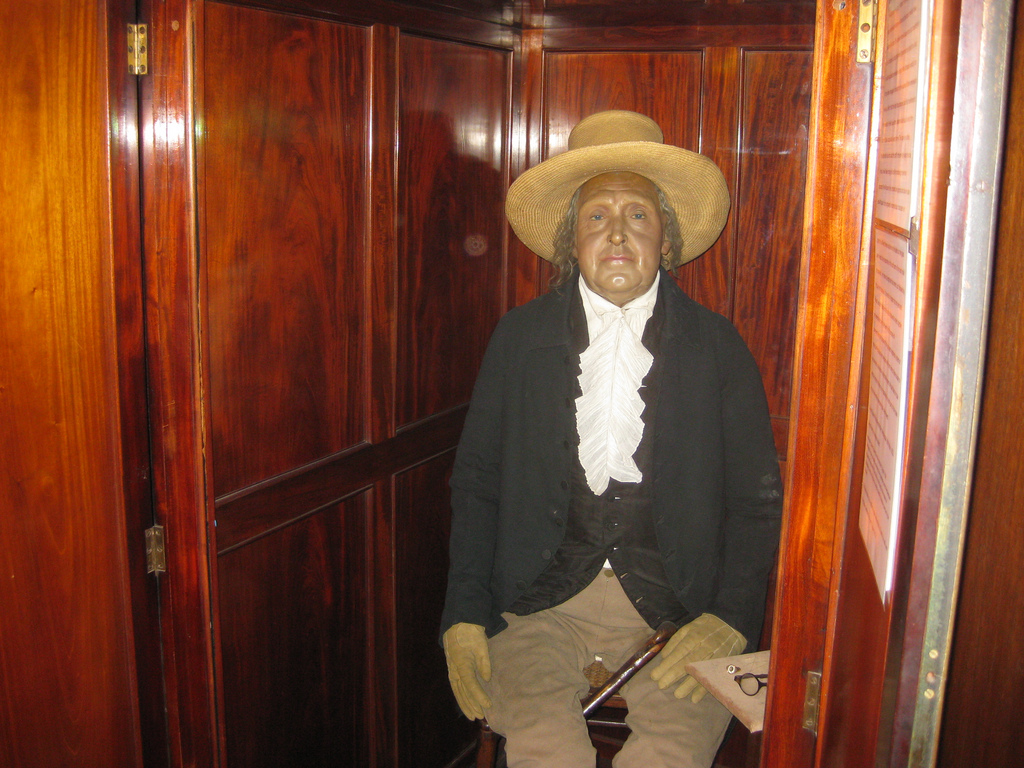

The roots of criminology; the past in the service of the future;

In a number of blog posts colleagues and myself (New Beginnings, Modern University or New University? Waterside: What an exciting time to be a student, Park Life, The ever rolling stream rolls on), we talked about the move to a new campus and the pedagogies it will develop for staff and students. Despite being in one of the newest campuses in the country, we also deliver some of our course content in the Sessions House. This is one of the oldest and most historic buildings in town. Sometimes with students we leave the modern to take a plunge in history in a matter of hours. Traditionally the court has been used in education primarily for mooting in the study of law or for reenactment for humanities. On this occasion, criminology occupies the space for learning enhancement that shall go beyond these roles.

The Sessions House is the old court in the centre of Northampton, built 1676 following the great fire of Northampton in 1675. The building was the seat of justice for the town, where the public heard unspeakable crimes from matricide to witchcraft. Justice in the 17th century appear as a drama to be played in public, where all could hear the details of those wicked people, to be judged. Once condemned, their execution at the gallows at the back of the court completed the spectacle of justice. In criminology discourse, at the time this building was founded, Locke was writing about toleration and the constrains of earthy judges. The building for the town became the embodiment of justice and the representation of fairness. How can criminology not be part of this legacy?

There were some of the reasons why we have made this connection with the past but sometimes these connections may not be so apparent or clear. It was in one of those sessions that I began to think of the importance of what we do. This is not just a space; it is a connection to the past that contains part of the history of what we now recognise as criminology. The witch trials of Northampton, among other lessons they can demonstrate, show a society suspicious of those women who are visible. Something that four centuries after we still struggle with, if we were to observe for example the #metoo movement. Furthermore, from the historic trials on those who murdered their partners we can now gain a new understanding, in a room full of students, instead of judges debating the merits of punishment and the boundaries of sentencing.

These are some of the reasons that will take this historic building forward and project it forward reclaiming it for what it was intended to be. A courthouse is a place of arbitration and debate. In the world of pedagogy knowledge is constant and ever evolving but knowing one’s roots allows the exploration of the subject to be anchored in a way that one can identify how debates and issues evolve in the discipline. Academic work can be solitary work, long hours of reading and assignment preparation, but it can also be demonstrative. In this case we a group (or maybe a gang) of criminologists explore how justice and penal policy changes so sitting at the green leather seats of courtroom, whilst tapping notes on a tablet. We are delighted to reclaim this space so that the criminologists of the future to figure out many ethical dilemmas some of whom once may have occupied the mind of the bench and formed legal precedent. History has a lot to teach us and we can project this into the future as new theoretical conventions are to emerge.

Locke J, (1689), A letter Concerning Toleration, assessed 01/11/18 https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/A_Letter_Concerning_Toleration

Findings on the ‘traditional lecture’ format – perfect timing!

I seem to be reading more and more reports on the need to retain lectures as a form of teaching, as it is claimed to ensure students are more engaged and committed to their studies when this method is used. Well, these findings have come to my attention just as I am testing online technologies to replace the ‘traditional’ lecture, via Collaborate on the new Waterside campus. Collaborate is a tool in Blackboard which opens an online classroom for students to join, listen to the lecture and see slides or other media, while also being able to pose questions via a chat function.

On the face of it, not so different, just the physical world replicated in the real world, right? Well, I will reserve judgement as I am still coming to grips with what this technology can do, I am aware younger generations of students may embrace this, and the reality is, it is the only forum I have to offer teaching to large numbers of students. I suspect student experiences are mixed, I know some really like it, some are not so keen, so again, not so different to lectures? The article in the times suggests that students are less likely to drop out if they are taught via lectures and have perceptions of good one-to-one contact with staff. Some more interesting issues were raised from replies in the tweet about the story, raising questions about the need to focus on quality, not method, that many universities are playing catch up with new teaching technologies and that this needs to be better understood from social and cultural perspectives. I think it is also worth picking up on perceptions of students, along with their expectations of higher education and remember, they must develop as independent learners. The setting in this respect would not seem to matter, it is the delivery, the level of effort put in to engage students and reinforcing the message that their learning is as much their responsibility as ours.

There is certainly a lot to grapple with, and for me, just starting out with this new technology, I myself feel there is much to learn and I am keeping an open mind. I do feel there are aspects of traditional teaching which must be retained and this can be done via group seminars, with smaller numbers and an opportunity for discussion, debate and student-led learning. If we see the lecture as the foundation for learning, then perhaps its method of delivery is less important. Given the online provision I must use for lectures, during seminars, I step away from the powerpoint and use the time I have with students in a more interactive way. For those modules where I don’t use online lectures, not much has changed on the new campus, but I am always keen to see how online teaching methods could be adopted – and I am prepared to use them if I genuinely can see their value.

It would be easy to offer only critique of this technology, and I think it is also important not to see it as an answer to the perennial problems with lack of engagement and focus many lecturers experience from mid term onwards. Perhaps online provision can at least overcome barriers to attendance for commuting students, those who feel intimidated in large lecture halls, and those who simply find they don’t engage with the material in this setting. At a time when some courses attract high numbers of students, and the reality of having lectures with 150+ students in a room means potential for noise disruption, lack of focus and interaction then maybe online provision can offer a meaningful alternative. There is provision for some interaction, time can be set aside for this, students can join in without worrying about disruption or not being able to hear the lecturer and it removes the need for lecturers to discipline disruptive behaviour. It does require some level of ‘policing’ and monitoring, but the settings can enable this. Having done lectures with 100 plus students, it is not something I miss – I’ve always preferred smaller seminar group teaching and so I can see how online provision can be a better support for this.

Currently, I use the online session as a form of recap and review, with some additional content for students. This is in part due the timing of the session and I am sure it can work equally as well as preparation for seminars. Students can then use the time to clarify anything they don’t understand and it reinforces themes and issues covered in seminars as well as introducing news ways to examine various topics. As with any innovation, this needs more research from across the board of disciplines and research approaches. In order to move such innovation on from ‘trial and error’ and simply hoping for the best, as with any policy we need to know what works, when it works and why. Therefore, along with my colleagues, I will persist and keep a watchful eye on the work of pedagogic experts out there who are examining this. There have been the inevitable issues with wifi not supporting connectivity – I can’t believe I just used this sentence about my teaching, but there it is. I am optimistic these issues will be overcome, and in the meantime, I always have a plan B – relying on technology is never a good plan (hence the featured image for this blog), but this is perhaps something to reflect on for another day.