Home » Learning (Page 8)

Category Archives: Learning

“My Favourite Things”: Bethany

My favourite TV show - I have many. But if I must select just one... Fleabag. I have rewatched several times, I have even read the book (which is more of a script). My favourite place to go - Peak district, I have several favourite spots within, but overall, it's my favourite place. My favourite city - Cambridge. It may be more familiarity than anything else, but it does have a charm. My favourite thing to do in my free time - READ. I have other loves, such as video games and walking. But reading is my everyday pastime. My favourite athlete/sports personality - Hard one for me, as I'm not really into sports. The only sport I follow which may surprise some is body-building! There's an element of obsession, dedication and art that fascinates me. So, I will say Kai Greene - but I'm not sure how many will know who this is. My favourite actor - Tough one, I like most films/TV that has either Bill Hader or Meryl Streep in. My favourite author - Tough one- Can I give 2 - is that cheating? Margaret Atwood & Lucy Clarke My favourite drink - Coca Cola - Full Fat - The good stuff My favourite food - Bangers & Mash My favourite place to eat - Anywhere with good food that I don't have to cook myself! I like people who - Ask Questions. Questions are the stepping-stone before acquiring knowledge. I don’t like it when people - Assume things stay the same. One of my pet peeves is "Well they should have thought of that before X happened". Things change, feelings change, people's finances change. Therefore, we should try withholding judgement and think how circumstances change. My favourite book - This one is hard for me. The academic in me says Paul Willis' Learning to Labour, the book opened my mind and genuinely changed my life. But the child in me and the one who loves to explore... The Secret Garden My favourite book character - This doesn't go in line with my favourite book, but I love the character Charmaine in The Heart Goes Last she's complex but she is also empathetic. My favourite film - Hocus Pocus - More of a sentimental thing of carving pumpkins every year while watching it! My favourite poem - While I am not one much for poetry, I adored Rupi Kaur's poetry book Milk and Honey My favourite artist/band - I have a few, I like The 1975, Alicia Keys, Sam Smith and even some Billie Eilish My favourite song - Not fitting at all to the above - But - It's Can't help falling in Love My favourite art - I didn't actually know the name of it till now as I never really thought about it, but what I used to call 'Crazy Stairs' (apparently actually called Relativity by M.C.Escher). It used to be in my Art room at school, I remember thinking it seemed pointless, then I realised that was probably the point. My favourite person from history - Angela Davis. After I read Women, Race & Class I wanted to explore more – This woman has had a fascinating, challenging, but above all, inspiring life.

… Side note: as I wasn’t asked … Maisie – My dog (pictured) is my favourite…of everything, really. Just look at her, she’s beautiful.

Empathy Amid the “Fake Tales of San Francisco”*

This time last week, @manosdaskalou and I were in San Francisco at the American Society of Criminology’s conference. This four-day meeting takes place once a year and encompasses a huge range of talkers and subjects, demonstrating the diversity of the discipline. Each day there are multiple sessions scheduled, making it incredibly difficult to choose which ones you want to attend.

Fortunately, this year both of our two papers were presented on the first day of the conference, which took some of the pressure off. We were then able to concentrate on other presenters’ work. Throughout discussions around teaching in prison, gun violence and many other matters of criminological importance, there was a sense of camaraderie, a shared passion to understand and in turn, change the world for the better. All of these discussions took place in a grand hotel, with cafes, bars and restaurants, to enable the conversation to continue long after the scheduled sessions had finished.

Outside of the hotel, there is plenty to see. San Francisco is an interesting city, famous for its Golden Gate Bridge, the cable cars which run up and down extraordinarily steep roads and of course, criminologically speaking, Alcatraz prison. In addition, it is renowned for its expensive designer shops, restaurants, bars and hotels. But as @haleysread has noted before, this is a city where you do not have to look far to find real deprivation.

I was last in San Francisco in 2014. At that point cannabis had been declassified from a misdemeanour to an infraction, making the use of the drug similar to a traffic offence. In 2016, cannabis was completely decriminalised for recreational use. For many criminologists, such decriminalisation is a positive step, marking a change from viewing drug use as a criminal justice problem, to one of public health. Certainly, it’s a position that I would generally subscribe to, not least as part of a process necessary to prison abolition. However, what do we really know about the effects of cannabis? I am sure my colleague @michellejolleynorthamptonacuk could offer some insight into the latest research around cannabis use.

When a substance is illegal, it is exceedingly challenging to research either its harms or its benefits. What we know, in the main, is based upon problematic drug use, those individuals who come to the attention of either the CJS or the NHS. Those with the means to sustain a drug habit need not buy their supplies openly on the street, where the risk of being caught is far higher. Thus our research population are selected by bad luck, either they are caught or they suffer ill-effects either with their physical or mental health.

The smell of cannabis in San Francisco is a constant, but there is also another aroma, which wasn’t present five years ago. That smell is urine. Furthermore, it has been well documented, that not only are the streets and highways of San Francisco becoming public urinals, there are also many reports that public defecation is an increasing issue for the city. Now I don’t want to be so bold as to say that the decriminalisation of cannabis is the cause of this public effluence, however, San Francisco does raise some questions.

- Does cannabis cause or exacerbate mental health problems?

- Does cannabis lead to a loss of inhibition, so much so that the social conventions around urination and defecation are abandoned?

- Does cannabis lead to an increase in homelessness?

- Does cannabis increase the likelihood of social problems?

- Does the decriminalisation of cannabis, lead to less tolerance of social problems?

I don’t have any of the answers, but it is extremely difficult to ignore these problems. The juxtaposition of expensive shops such as Rolex and Tiffany just round the corner from large groups of confused, homeless people, make it impossible to avoid seeing the social problems confronted by this city. Of course, poor mental health and homelessness are not unique to San Francisco or even the USA, we have similar issues in our own town, regardless of the legal status of cannabis. Certainly the issue of access to bathroom facilities is pressing; should access to public toilets be a right or a privilege? This, also appears to be a public health, rather than CJS problem, although those observing or policing such behaviour, may argue differently.

Ultimately, as @haleysread found, San Francisco remains a City of Contrast, where the very rich and the very poor rub shoulders. Unless, society begins to think a little more about people and a little less about business, it seems inevitable that individuals will continue to live, eat, urinate and defection and ultimately, die upon the streets. It is not enough to discuss empathy in a conference, no matter how important that might be, if we don’t also empathise with people whose lives are in tatters.

*Turner, Alex, (2006), Fake Tales of San Francisco, [CD]. Recorded by Arctic Monkeys in Whatever People Say I Am, That’s What I’m Not, The Chapel: Domino Records

Terrorised into compliance

Learning and teaching is a complex business, difficult to describe even by those in the process of either/or both. Pedagogy, as defined by Lexico is ‘[t]he method and practice of teaching, especially as an academic subject or theoretical concept’. It underpins all teaching activity and despite the seemingly straightforward definition, is a complex business. At university, there are a variety of pedagogies both across and within disciplines. How to teach, is as much of a hot topic, as what to teach and the methods and practices are varied.

So how would you feel if I said I wanted Criminology students to quake in their boots at the prospect of missing classes? Or “literally feel terror” at the thought of failing to do their reading or not submitting an assessment? Would you see this as a positive attempt to motivate an eager learner? A reaction to getting the best out of lazy or recalcitrant students? A way of instilling discipline, keeping them on the straight and narrow on the road to achieving success? After all, if the grades are good then everything must be okay? Furthermore, given many Criminology graduate go on to careers within Foucault’s ‘disciplinary society’ maybe it would be useful to give them a taste of what’s to come for the people they deal with (1977: 209).

Hopefully, you are aghast that I would even consider such an approach (I promise, I’m definitely not) and you’ve already thought of strong, considered arguments as to why this would be a very bad idea Yet, last week the new Home Secretary, Pritti Patel stated that she wanted people to “literally feel terror” at the prospect of becoming involved in crime. Although presented as a novel policy, many will recognise this approach as firmly rooted in ideas from the Classical School of Criminology. Based on the concepts of certainty, celerity and severity, these ideas sought to move away from barbaric notions and practices to a more sophisticated understanding of crime and punishment.

Deterrence (at the heart of Classical School thought) can be general or specific; focused on society or individuals. Patel appears to be directing her focus on the latter, suggesting that feelings of “terror” will deter individuals from committing crime. Certainly, one of the classical school’s primary texts, On Crime and Punishment addresses this issue:

‘What is the political intention of punishments? To terrify, and to be an example to others. Is this intention answered, by thus privately torturing the guilty and the innocent?’

(Beccaria, 1778: 64)

So, let’s think through this idea of terrorising people away from crime, could it work? As I’ve argued before if your crime is a matter of conscience it is highly unlikely to work (think Conscientious Objectors, Suffragettes, some terrorists). If it is a crime of necessity, stealing to feed yourself or your family, it is also unlikely to succeed, certainly the choice between starvation and crime is terrifying already. What about children testing boundaries with peers, can they really think through all the consequences of actions, research suggests that may not be case (Rutherford, 1986/2002). Other scenarios could include those under the influence of alcohol/drugs and mental health illnesses, both of which may have an impact on individual ability to think through problems and solutions. All in all, it seems not everyone can be deterred and furthermore, not all crimes are deterrable (Jacobs, 2010). So much for the Home Secretary’s grand solution to crime.

As Drillminister demonstrates to powerful effect, violent language is contextual (see @sineqd‘s discussion here). Whilst threats to kill are perceived as violence when uttered by young, black men in hoods, in the mouths of politicians they apparently lose their viciousness. What should we then make of Pritti Patel’s threats to make citizens “literally feel terror”?

Selected bibliography

Beccaria, Cesare, (1778), An Essay on Crimes and Punishments, (Edinburgh: Alexander Donaldson), [online]. Available from: https://archive.org/details/essayoncrimespu00Becc/page/n3

Foucault, Michel, (1977), Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, tr. from the French by Alan Sheridan, (London: Penguin Books)

Jacobs, Bruce A., (2010), ‘Deterrence and Deterrability’, Criminology, 48, 2: 417-441

Rutherford, Andrew, (1986/2002), Growing Out of Crime: The New Era, (Winchester: Waterside Press)

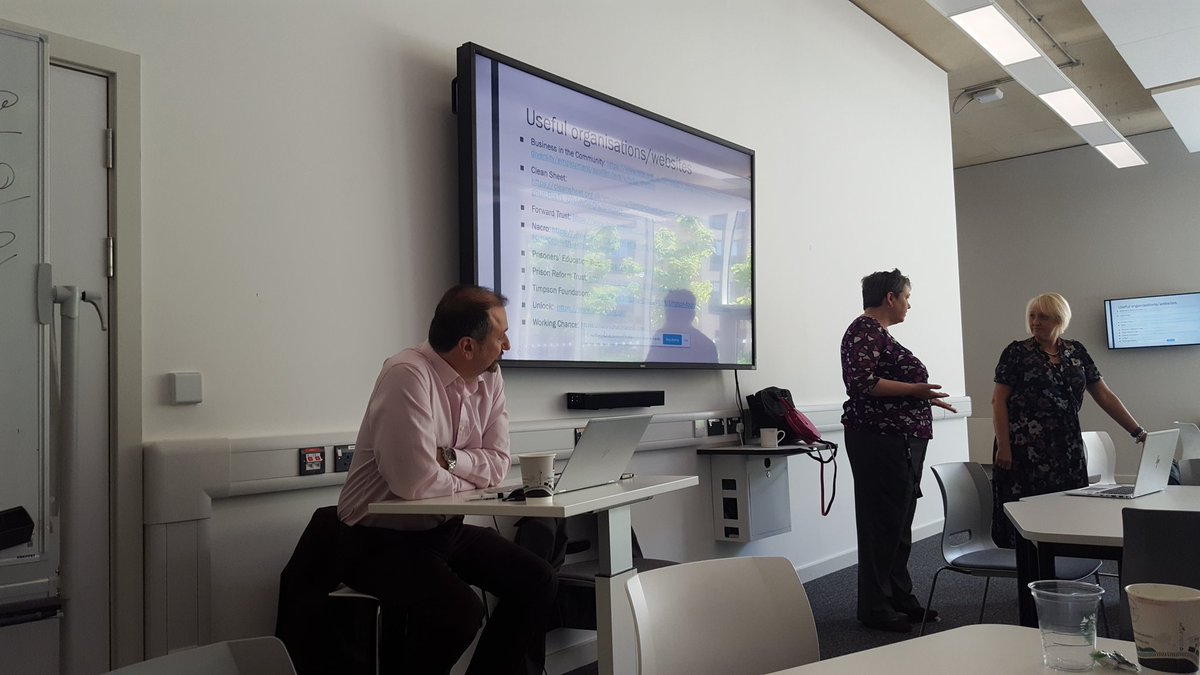

Thinking “outside the box”

Having recently done a session on criminal records with @paulaabowles to a group of voluntary, 3rd sector and other practitioners I started thinking of the wider implications of taking knowledge out of the traditional classroom and introducing it to an audience, that is not necessarily academic. When we prepare for class the usual concern is the levelness of the material used and the way we pitch the information. In anything we do as part of consultancy or outside of the standard educational framework we have a different challenge. That of presenting information that corresponds to expertise in a language and tone that is neither exclusive nor condescending to the participants.

In the designing stages we considered the information we had to include, and the session started by introducing criminology. Audience participation was encouraged, and group discussion became a tool to promote the flow of information. Once that process started and people became more able to exchange information then we started moving from information to knowledge exchange. This is a more profound interaction that allows the audience to engage with information that they may not be familiar with and it is designed to achieve one of the prime quests of any social science, to challenge established views.

The process itself indicates the level of skill involved in academic reasoning and the complexity associated with presenting people with new knowledge in an understandable form. It is that apparent simplicity that allows participants to scaffold their understanding, taking different elements from the same content. It is easy to say to any audience for example that “every person has an opinion on crime” however to be able to accept this statement indicates a level of proficiency on receiving views of the other and then accommodating it to your own understanding. This is the basis of the philosophy of knowledge, and it happens to all engaged in academia whatever level, albeit consciously or unconsciously.

As per usual the session overran, testament that people do have opinions on crime and how society should respond to them. The intriguing part of this session was the ability of participants to negotiate different roles and identities, whilst offering an explanation or interpretation of a situation. When this was pointed out they were surprised by the level of knowledge they possessed and its complexity. The role of the academic is not simply to advance knowledge, which is clearly expected, but also to take subjects and contextualise them. In recent weeks, colleagues from our University, were able to discuss issues relating to health, psychology, work, human rights and consumer rights to national and local media, informing the public on the issues concerned.

This is what got me thinking about our role in society more generally. We are not merely providing education for adults who wish to acquire knowledge and become part of the professional classes, but we are also engaging in a continuous dialogue with our local community, sharing knowledge beyond the classroom and expanding education beyond the campus. These are reasons which make a University, as an institution, an invaluable link to society that governments need to nurture and support. The success of the University is not in the students within but also on the reach it has to the people around.

At the end of the session we talked about a number of campaigns to help ex-offenders to get forward with work and education by “banning the box”. This was a fitting end to a session where we all thought “outside the box”.

And time waits for no one, and it won’t wait for me*

Last week in my blog I mentioned that time is finite, and certainly where mere mortals are concerned. I want to extend that notion of finite time a little further by considering the concepts of constraints placed upon our time by what might at times be arbitrary processes and other times the natural order of things.

There are only 24 hours in a day, such an obvious statement, but one which provides me with a good starting point. Within that twenty fours we need to sleep and eat and perform other necessary functions such as washing etc. This leaves us only a certain amount of time in which we can perform other functions such as work or study. If we examine this closer, it becomes clear that the time available to us is further reduced by other ‘stuff’ we do. I like the term ‘stuff’ because everyone has a sense of what it is, but it doesn’t need to be specific. ‘Stuff’ in this instance might be, travelling to and from work or places of study, it might be setting up a laptop ready to work, making a cup of coffee, popping to the toilet, having a conversation with a colleague or someone else, either about work or something far more interesting, or taking a five-minute break from the endless staring at a computer screen. The point is that ‘stuff’ is necessary but it eats into our time and consequently the time to work or study is limited. My previous research around police patrol staffing included ‘stuff’, managerialists would turn in their graves, and therefore it became rapidly apparent that availability to do patrol work was only just over half the shift. So, thinking about time and how finite it is, we only have a small window in a 24-hour period to do work or study. Reduced even further if we try to do both.

I mentioned in my previous blog that I’m renovating a house and have carried out most of the work myself. We have a moving in date, a bit arbitrary but there are financial implications of not moving in on that date, so the date is fixed. One of the skills that I have yet to master is plastering. I can patch plaster but whole walls are currently just not feasible. I know this, having had to scrape plaster from several walls in the past and the fact that there was more plaster on the floor and me than there was on the wall. I also know that with some coaching and practice, over time, I could become quite accomplished, but I do not have time as the moving in date is fixed. And so, I employ plasterers to do the work. But what if I could not employ plasterers, what if, I had to do the work myself and I had to learn to do it whilst the deadline is fast approaching? Time is finite, I can try to extend it a little by spending more time learning in each 24-hour segment but ‘stuff’, my proper job and necessary functions such as sleeping will limit what I can do. Inevitably the walls will not be plastered when we move in or the walls will be plastered but so will the floor and me. I will probably be plastered in a different sense from sheer exacerbation. The knock-on effect is that I cannot move on to learn about, let alone carry out, decorating or carpet fitting or floor laying or any part of renovating a house.

As the work on the house progresses, I have become increasingly tired, but the biggest impact has been that my knees have really started to give me trouble to the extent that some days walking up and down stairs is a slow and painful process. I am therefore limited as to how quickly I can do things by my temporary disability. Where it took me a few minutes to carry something up the stairs, it now takes two to three times the amount of time. So, more time is required to do the work and there is still the need to sleep and do ‘stuff’ in a finite time that is rapidly running out.

You might think well so what? Let me ask you now to think about students in higher education. Using my plastering skills as an analogy, what if students embarking on higher education do not have the basic skills to the standard that higher education requires? What if they can read (patch plaster) but are not able to read to the standard that is needed (plastering whole walls)? How might we start to take them onto bigger concepts, how might they understand how to carry out a literature review for example? Time is not waiting for them to learn the basics, time moves on, there is a set time in which to complete a degree. Just as I cannot decorate until the walls are plastered so too can the students not embark on higher education studies until they have the ability to read to a requisite standard. So, what would the result be? Probably no assignments completed, or completed very poorly or perhaps, just as I have paid for plastering to be done….

Now think about my temporary disability, what if, like me, it takes students twice as long to complete a task, such as reading an article, because they have a disability? There is only so much time in a day and if they, like everyone else, have ‘stuff’ to do then is it not possible that they are likely to run out of time? We give students with learning difficulties and disabilities extra time in exams, but where is the extra time in the course of weekly learning? We accept that those with disabilities have to work harder, but if working harder means spending more time on something then what are they not spending time on? Why should students with disabilities have less time to do ‘stuff’?

The structure and processes within HE fails to take cognisance of time. Surely a rethink is needed if HE is not to be condemned as institutionally failing those with disabilities and learning difficulties. Widening participation has widening implications that seem to have been neglected. I’ll leave you with those thoughts, a quick glance at my watch and I had best go because in the words of the white rabbit, ‘Oh dear! Oh dear! I shall be late’ (Carroll, 1998: 10).

Carroll, L. (1998) Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass: The centenary edition, London: Penguin books.

*Richards, K. and Jagger, M (1974) Time waits for no one. Warner/Chappell Music, Inc.

The Lure of Anxiety

Helen is an Associate Lecturer teaching on modules in years 1 and 3.

I wear several hats in life, but I write this blog in the role of a lecturer and a psychologist, with experience in the theory and practice of working with people with psychological disorders.

In recent years, there has been an increase in awareness of mental health problems. This is very welcome. Celebrities have talked openly about their own difficulties and high profile campaigns encourage us to bring mental health problems out of the shadows. This is hugely beneficial. When people with mental health problems suffer in silence their suffering is invariably increased, and simply talking and being listened to is often the most important part of the solution.

But with such increased awareness, there can also be well-intentioned but misguided responses which make things worse. I want to talk particularly about anxiety (which is sometimes lumped together with depression to give a diagnosis of “anxiety and depression” – they can and do often occur together but they are different emotions which require different responses). Anxiety is a normal emotion which we all experience. It is essential for survival. It keeps us safe. If children did not experience anxiety, they would wander away from their parents, put their hands in fires, fall off high surfaces or get run over by cars. Low levels of anxiety are associated with dangerous behaviour and psychopathy. High levels of anxiety can, of course, be extremely distressing and debilitating. People with anxiety disorders avoid the things they fear to the point where their lives become smaller and smaller and their experience severely restricted.

Of course we should show compassion and understanding to people who suffer from anxiety disorders and some campaigners have suggested that mental health problems should receive the same sort of response as physical health problems. However, psychological disorders, including anxiety disorders, do not behave like physical illnesses. It is not a case of diagnosing a particular “bug” and then prescribing the appropriate medication or therapy to make it go away (in reality, many physical conditions do not behave like this either). Anxiety thrives when you feed it. The temptation when you suffer high levels of anxiety is to avoid the thing that makes you anxious. But anyone who has sat through my lecture on learning theory should remember that doing something that relieves or avoids a negative consequence leads to negative reinforcement. If you avoid something that makes you highly anxious (or do something that temporarily relieves the anxiety, such as repeatedly washing your hands, or engaging in a ritual) the avoidance behaviour will be strongly reinforced. And you never experience the target of your fears, so you never learn that nothing catastrophic is actually going to happen – in other words you prevent the “extinction” that would otherwise occur. So the anxiety just gets worse and worse and worse. And your life becomes more and more restricted.

So, while we should, of course be compassionate and supportive towards people with anxiety disorders, we should be careful not to feed their fears. I remember once becoming frustrated with a member of prison staff who proudly told me how she was supporting a prisoner with obsessive-compulsive disorder by allowing him to have extra cleaning materials. No! In doing so, she was facilitating his disorder. What he needed was support to tolerate a less than spotless cell, so that he could learn through experience that a small amount of dirt does not lead to disaster. Increasingly, we find ourselves teaching students with anxiety difficulties. We need to support and encourage them, to allow them to talk about their problems, and to ensure that their university experience is positive. But we do them no favours by removing challenges or allowing them to avoid the aspects of university life that they fear (such as giving presentations or working in groups). In doing so, we make life easier in the short-term, but in the long-term we feed their disorders and make things worse. As I said earlier, we all experience anxiety and the best way to prevent it from controlling us is to stare it in the face and get on with whatever life throws at us.