Home » Judge

Category Archives: Judge

Exploring the National Museum of Justice: A Journey Through History and Justice

As Programme Leader for BA Law with Criminology, I was excited to be offered the opportunity to attend the National Museum of Justice trip with the Criminology Team which took place at the back end of last year. I imagine, that when most of us think about justice, the first thing that springs to mind are courthouses filled with judges, lawyers, and juries deliberating the fates of those before them. However, the fact is that the concept of justice stretches far beyond the courtroom, encompassing a rich tapestry of history, culture, and education. One such embodiment of this multifaceted theme is the National Museum of Justice, a unique and thought-provoking attraction located in Nottingham. This blog takes you on a journey through its historical significance, exhibits, and the essential lessons it imparts and reinforces about justice and society.

A Historical Overview

The National Museum of Justice is housed in the Old Crown Court and the former Nottinghamshire County Gaol, which date back to the 18th century. This venue has witnessed a myriad of legal proceedings, from the trials of infamous criminals to the day-to-day workings of the justice system. For instance, it has seen trials of notable criminals, including the infamous Nottinghamshire smuggler, and it played a role during the turbulent times of the 19th century when debates around prison reform gained momentum. You can read about Richard Thomas Parker, the last man to be publicly executed and who was hanged outside the building here. The building itself is steeped in decade upon decade of history, with its architecture reflecting the evolution of legal practices over the centuries. For example, High Pavement and the spot where the gallows once stood.

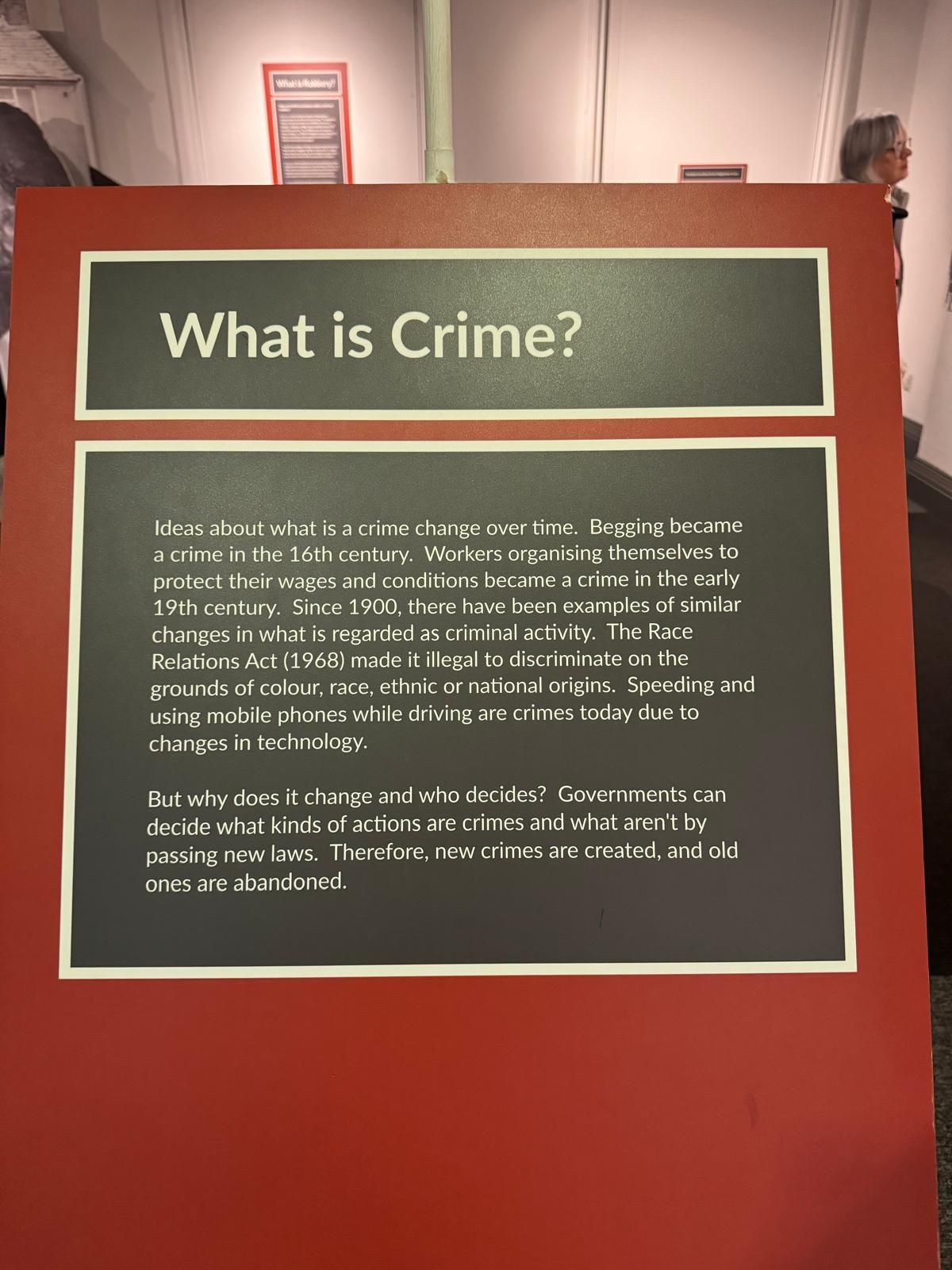

By visiting the museum, it is possible to trace the origins of the British legal system, exploring how societal values and norms have shaped the laws we live by today. The National Museum of Justice serves as a reminder that justice is not a static concept; it evolves as society changes, adapting to new challenges and perspectives. For example, one of my favourite exhibits was the bench from Bow Street Magistrates Court. The same bench where defendants like Oscar Wilde, Mick Jagger and the Suffragettes would have sat on during each of their famous trials. This bench has witnessed everything from defendants being accused of hacking into USA Government computers (Gary McKinnon), Gross Indecency (Oscar Wilde), Libel (Jeffrey Archer), Inciting a Riot (Emmeline Pankhurst) as well as Assaulting a Police Officer (Miss Dynamite).

Understanding this rich history invites visitors to contextualize the legal system and appreciate the ongoing struggle for a just society.

Engaging Exhibits

The National Museum of Justice is more than just a museum; it is an interactive experience that invites visitors to engage with the past. The exhibits are thoughtfully curated to provide a comprehensive understanding of the legal system and its historical context. Among the highlights are:

1. The Criminal Courtroom: Step into the courtroom where real trials were once held. Here, visitors can learn about the roles of various courtroom participants, such as the judge, jury, and barristers. This is the same room that the Criminology staff and students gathered in at the end of the day to share our reflections on what we had learned from our trip. Most students admitted that it had reinforced their belief that our system of justice had not really changed over the centuries in that marginalised communities still were not dealt with fairly.

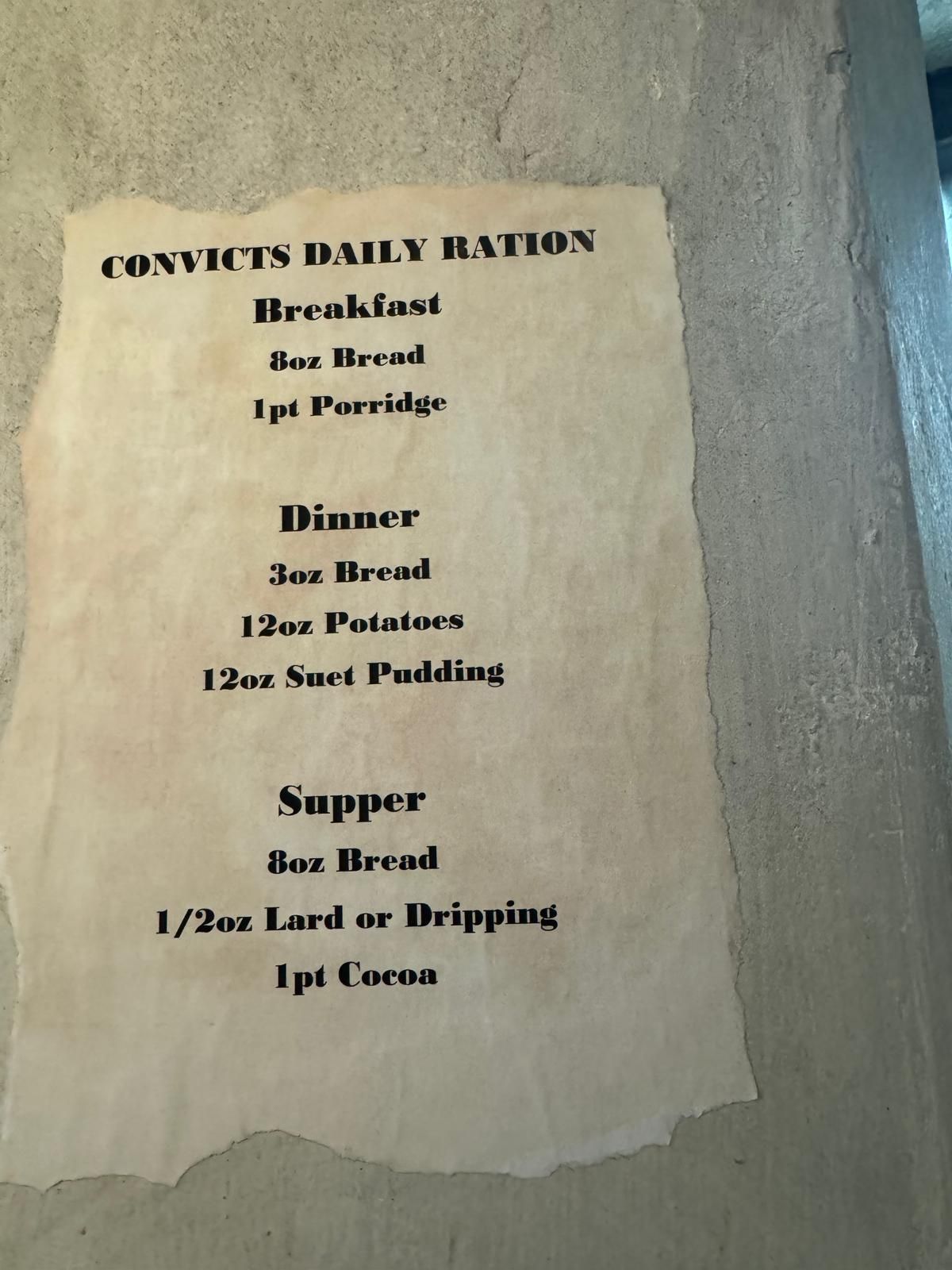

2. The Gaol: We delved into the grim reality of life in prison during the Georgian and Victorian eras. The gaol section of the gallery offers a sobering look at the conditions inmates faced, emphasizing the societal implications of punishment and rehabilitation. For example, every prisoner had to pay for his/ her own food and once their sentence was up, they would not be allowed to leave the prison unless all payments were up to date. The stark conditions depicted in this exhibit encourage reflections on the evolution of prison systems and the ongoing debates surrounding rehabilitation versus punishment. Eventually, in prisons, women were taught skills such as sewing and reading which it was hoped may better their chances of a successful life in society post release. This was an evolution within the prison system and a step towards rehabilitation of offenders rather than punishment.

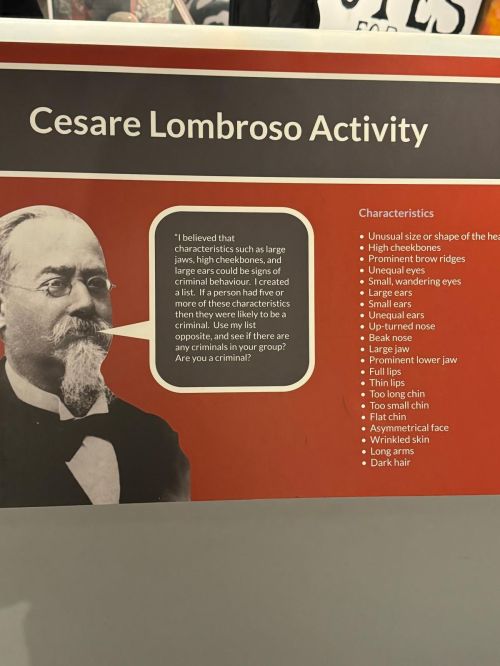

3. The Crime and Punishment Exhibit: This exhibit examines the relationship between crime and society, showcasing the changing perceptions of criminal behaviour over time. For example, one famous Criminologist of the day Cesare Lombroso, once believed that it was possible to spot a criminal based on their physical appearance such as high cheekbones, small ears, big ears or indeed even unequal ears. Since I was not familiar with Lombroso or his work, I enquired with the Criminology department as to studies that he used to reach the above conclusions. Although I believe he did carry out some ‘chaotic’ studies, it really reminded me that it is possible to make statistics say whatever it is you want them to say. This is the same point in relation to the law generally. As a lawyer I can make the law essentially say whatever I want it to say in the way I construct my arguments and the sources I include. Overall, The Inclusions of such exhibits raises and attempts to tackle difficult questions about personal and societal morality, justice, and the impact of societal norms on individual actions. By examining such leading theories of the time and their societal reactions, the exhibit encourages visitors to consider the broader implications of crime and the necessity of reform within the justice system. Do you think that today, deciding whether someone is a criminal based on their physical appearance would be acceptable? Do we in fact still do this? If we do, then we have not learned the lessons from history or really moved on from Cesare Lombroso.

Lessons on Justice and Society

The National Museum of Justice is not merely a historical site; it also serves as a platform for discussions about contemporary issues related to justice. Through its exhibits and programs, our group was invited to reflect on essentially- The Evolution of Justice: Understanding how laws have changed (or not!) over time helps us appreciate the progress (or not!) made in human rights and justice and with particular reference to women. It also encourages us to consider what changes may still be needed. For example, we were incredibly privileged to be able to access the archives at the museum and handle real primary source materials. We, through official records followed the journey of some women and girls who had been sent to reform schools and prisons. Some were given extremely long sentences for perhaps stealing a loaf of bread or reel of cotton. It seemed to me that just like today, there it was- the huge link between poverty and crime. Yet, what have we done about this in over two or three hundred years? This focus on historical cases illustrates the importance of learning from the past to inform present and future legal practices.

– The Importance of Fair Trials: The gallery emphasizes the significance of due process and the presumption of innocence, reminding us that justice must be impartial and equitable. In a world where public opinion can often sway perceptions of guilt or innocence, this reminder is particularly pertinent. The National Museum of Justice underscores the critical role that fair trials play in maintaining the integrity of the legal system. For example, if you were identified as a potential criminal by Cesare Lombroso (who I referred to above) then you were probably not going to get a fair trial versus an individual who had none of the characteristics referred to by his studies.

– Societal Responsibility: The exhibits prompt discussions about the role of society in shaping laws and the collective responsibility we all share in creating a just environment. The National Museum of Justice encourages visitors to think about their own roles in advocating for justice, equality, and reform. It highlights that justice is not solely the responsibility of legal professionals but also of the community at large.

– Ethics and Morality: The museum offers a platform to explore ethical dilemmas and moral questions surrounding justice. Engaging with historical cases can lead to discussions about right and wrong, prompting visitors to consider their own beliefs and biases regarding justice.

Conclusion

The National Museum of Justice in Nottingham is a remarkable destination that beautifully intertwines history, education, and advocacy for justice. By exploring its rich exhibits and engaging with its thought-provoking themes, visitors gain a deeper understanding of the complexities surrounding justice and its vital role in society. Whether you are a history buff, a legal enthusiast, a Criminologist or simply curious about the workings of justice, the National Museum of Justice offers a captivating journey that will leave you enlightened and inspired.

As we navigate the complexities of the modern world, it is essential to remember the lessons of the past and continue striving for a fair and just society for all. The National Museum of Justice stands as a powerful testament to the ongoing quest for justice, inviting us all to be active participants in that journey. In doing so, we honour the legacy of those who have fought for justice throughout history and commit ourselves to ensuring that the principles of fairness and equity remain at the forefront of our society. Sitting on that same bench that Emmeline Pankhurst once sat really reminded me of why I initially studied law.

The main thought that I was left with as I left the museum was that justice is not just a concept; it is a lived experience that we all contribute to shaping.

What price justice?

Having read a colleague’s blog Is justice fair?, I turned my mind to recent media coverage regarding the prosecution rates for rape in England and Wales. Just as a reminder, the coverage concerned the fact that the number of prosecutions is at an all-time low with a fall of 932 or 30.75% with the number of convictions having fallen by 25%. This is coupled with a falling number of cases charged when compared with the year 2015/16. The Victims’ Commissioner Dame Vera Baird somewhat ironically, was incensed by these figures and urged the Crown Prosecution Service to change its policy immediately.

I’m always sceptical about the use of statistics, they are just simple facts, manipulated in some way or another to tell a story. Useful to the media and politicians alike they rarely give us an explanation of underlying causes and issues. Dame Vera places the blame squarely on the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) and its policy of only pursuing cases that are likely to succeed in court. Now this is the ironic part, as a former Labour member of parliament, a minister and Solicitor General for England and Wales, she would have been party to and indeed helped formalise and set CPS policy and guidelines. The former Labour Government’s propensity to introduce targets and performance indicators for the public services knew no bounds. If its predecessors, the Conservatives were instrumental in introducing and promulgating these management ideals, the Labour government took them to greater heights. Why would we be surprised then that the CPS continue in such a vein? Of course, add in another dimension, that of drastic budget cuts to public services since 2010, the judicial system included, and the pursuit of rationalisation of cases looks even more understandable and if we are less emotional and more clinical about it, absolutely sensible.

My first crown court case involved the theft of a two-bar electric fire. A landlady reported that a previous tenant had, when he moved out, taken the fire with him. As a young probationary constable in 1983, I tracked down the culprit, arrested him and duly charged him with the offence of theft. Some months later I found myself giving evidence at crown court. As was his right at the time, the defendant had elected trial by jury. The judicial system has moved a long way since then. Trial by jury is no longer allowed for such minor offences and of course the police no longer have much say in who is prosecuted and who isn’t certainly when comes to crown court cases. Many of the provisions that were in place at the time protected the rights of defendants and many of these have been diminished, for the most part, in pursuit of the ‘evil three Es’; economy, effectiveness and efficiency. Whilst the rights of defendants have been diminished, so too somewhat unnoticed, have the rights of victims. The lack of prosecution of rape cases is not a phenomenon that stands alone. Other serious cases are also not pursued or dropped in the name of economy or efficiency or effectiveness. If all the cases were pursued, then the courts would grind to a halt such have been the financial cuts over the years. Justice is expensive whichever way you look at it.

My colleague is right in questioning the fairness of a system that seems to favour the powerful, but I would add to it. The pursuit of economy is indicative that the executive is not bothered about justice. To borrow my colleague’s analogy, they want to show that there is an ice cream but the fact that it is cheap, and nasty is irrelevant.

The roots of criminology; the past in the service of the future;

In a number of blog posts colleagues and myself (New Beginnings, Modern University or New University? Waterside: What an exciting time to be a student, Park Life, The ever rolling stream rolls on), we talked about the move to a new campus and the pedagogies it will develop for staff and students. Despite being in one of the newest campuses in the country, we also deliver some of our course content in the Sessions House. This is one of the oldest and most historic buildings in town. Sometimes with students we leave the modern to take a plunge in history in a matter of hours. Traditionally the court has been used in education primarily for mooting in the study of law or for reenactment for humanities. On this occasion, criminology occupies the space for learning enhancement that shall go beyond these roles.

The Sessions House is the old court in the centre of Northampton, built 1676 following the great fire of Northampton in 1675. The building was the seat of justice for the town, where the public heard unspeakable crimes from matricide to witchcraft. Justice in the 17th century appear as a drama to be played in public, where all could hear the details of those wicked people, to be judged. Once condemned, their execution at the gallows at the back of the court completed the spectacle of justice. In criminology discourse, at the time this building was founded, Locke was writing about toleration and the constrains of earthy judges. The building for the town became the embodiment of justice and the representation of fairness. How can criminology not be part of this legacy?

There were some of the reasons why we have made this connection with the past but sometimes these connections may not be so apparent or clear. It was in one of those sessions that I began to think of the importance of what we do. This is not just a space; it is a connection to the past that contains part of the history of what we now recognise as criminology. The witch trials of Northampton, among other lessons they can demonstrate, show a society suspicious of those women who are visible. Something that four centuries after we still struggle with, if we were to observe for example the #metoo movement. Furthermore, from the historic trials on those who murdered their partners we can now gain a new understanding, in a room full of students, instead of judges debating the merits of punishment and the boundaries of sentencing.

These are some of the reasons that will take this historic building forward and project it forward reclaiming it for what it was intended to be. A courthouse is a place of arbitration and debate. In the world of pedagogy knowledge is constant and ever evolving but knowing one’s roots allows the exploration of the subject to be anchored in a way that one can identify how debates and issues evolve in the discipline. Academic work can be solitary work, long hours of reading and assignment preparation, but it can also be demonstrative. In this case we a group (or maybe a gang) of criminologists explore how justice and penal policy changes so sitting at the green leather seats of courtroom, whilst tapping notes on a tablet. We are delighted to reclaim this space so that the criminologists of the future to figure out many ethical dilemmas some of whom once may have occupied the mind of the bench and formed legal precedent. History has a lot to teach us and we can project this into the future as new theoretical conventions are to emerge.

Locke J, (1689), A letter Concerning Toleration, assessed 01/11/18 https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/A_Letter_Concerning_Toleration