Home » Human Rights (Page 6)

Category Archives: Human Rights

The true message of Christmas

One of the seasonal discussions we have at social fora is how early the Christmas celebrations start in the streets, shops and the media. An image of snowy landscapes and joyful renditions of festive themes that appear sometime in October and intensify as the weeks unforld. It seems that every year the preparations for the festive season start a little bit earlier, making some of us to wonder why make this fuss? Employees in shops wearing festive antlers and jumpers add to the general merriment and fun usually “enforced” by insistent management whose only wish is to enhance our celebratory mood. Even in my classes some of the students decided to chip in the holiday fun wearing oversized festive jumpers (you know who you are!). In one of those classes I pointed out that this phenomenon panders to the commercialisation of festivals only to be called a “grinch” by one of the gobby ones. Of course all in good humour, I thought.

Nonetheless it was strange considering that we live in a consumerist society that the festive season is marred with the pressure to buy as much food as possible so much so, that those who cannot (according to a number of charities) feel embarrassed to go shopping; or the promotion of new toys, cosmetics and other trendy items that people have to have badly wrapped ready for the big day. The emphasis on consumption is not something that happened overnight. There have been years of making the special season into a family event of Olympic proportions. Personal and family budgets will dwindle in the need to buy parcels of goods, consume volumes of food and alcohol so that we can rejoice.

Many of us by the end of the festive season will look back with regret, for the pounds we put on, the pounds we spent and the things we wanted to do but deferred them until next Christmas. Which poses the question; What is the point of the holiday or even better, why celebrate Christmas anymore? Maybe a secular society needs to move away from religious festivities and instead concentrate on civic matters alone. Why does religion get to dictate the “season to be jolly” and not people’s own desire to be with the ones they want to be with? If there is a message within the religious symbolism this is not reflected in the shop-windows that promote a round-shaped old man in red, non-existent (pagan) creatures and polar animals.

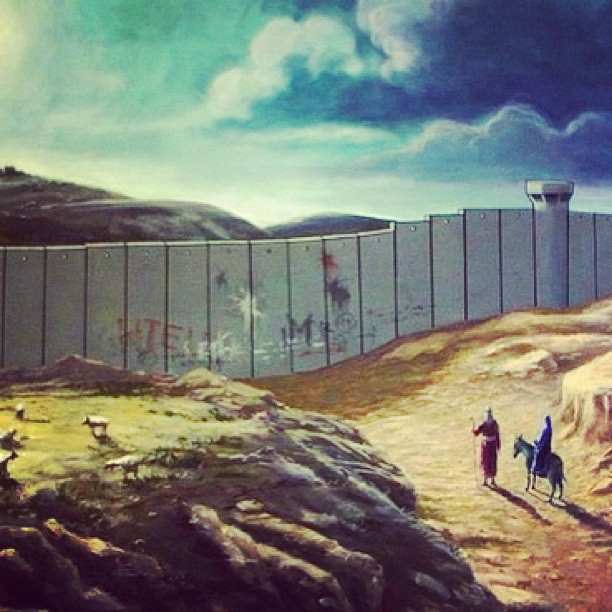

According to the religious message about 2000 years ago a refugee family gave birth to a child on their way to exile. The child would live for about 33 years but will change the face of modern religion. He promised to come back and millions of people still wait for his second coming but in the meantime millions of refugee children are piling up in detention centers and hundreds of others are dying in the journey of the damned. “A voice is heard in Ramah, mourning and great weeping, Rachel weeping for her children, because her children are no more” (Jeremiah 31:15). This is the true message of Christmas today.

Happy Holidays to our students and colleagues.

FYI: Ramah is a town in war torn Middle East

“Letters from America”: III

For those of you who follow The Criminology Team on Facebook you might have caught @manosdaskalou and I live from Eastern State Penitentiary [ESP]. In this entry, I plan to reflect on that visit in a little more depth.

For those of you who follow The Criminology Team on Facebook you might have caught @manosdaskalou and I live from Eastern State Penitentiary [ESP]. In this entry, I plan to reflect on that visit in a little more depth.

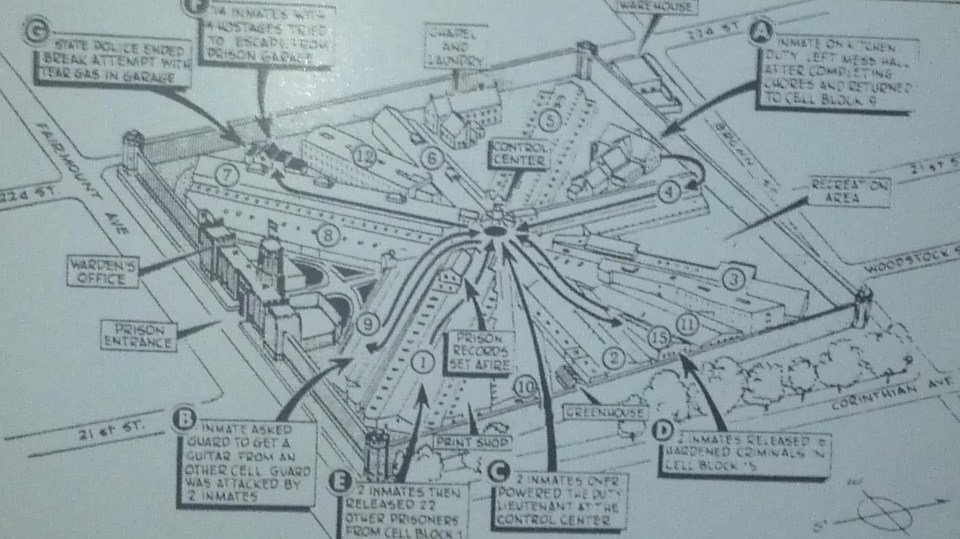

We first visited ESP in 2011 when the ASC conference was held in Washington, DC. That visit has never left me for a number of reasons, not least the lengths societies are prepared to go in order to tackle crime. ESP is very much a product of its time and demonstrates extraordinarily radical thinking about crime and punishment. For those who have studied the plans for Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon there is much which is familiar, not least the radial design (see illustration below).

This is an institution designed to resolve a particular social problem; crime and indeed deter others from engaging in similar behaviour through humane and philosophically driven measures. The Philadelphia Society for Alleviating the Miseries of Public Prisons* was philanthropic and guided by religious principles. This is reflected in the term penitentiary; a place for sinners to repent and In turn become truly penitent.

This philosophy was distinct and radical with a focus on reformation of character rather than brutal physical punishment. Of course, scholars such as Ignatieff and Foucault have drawn attention to the inhumanity of such a regime, whether deliberate or unintentional, but that should not detract from its groundbreaking history. What is important, as criminologists, is to recognise ESP’s place in the history of penology. That history is one of coercion, pleading, physical and mental brutality and still permeates all aspects of incarceration in the twenty-first century. ESP have tried extremely hard to demonstrate this continuum of punishment, acknowledging its place among many other institutions both home and abroad.

For me the question remains; can we make an individual change their behaviour through the pains of incarceration? I have argued previously in this blog in relation to Conscientious Objectors, that all the evidence suggests we cannot. ESP, as daunting as it may have been in its heyday, would also seem to offer the same answer. Until society recognises the harm and futility of incarceration it is unlikely that penal reform, let alone abolition, will gain traction.

*For those studying CRI1007 it is worth noting the role of Benjamin Rush in this organisation.

Leave my country

One image, one word, one report can generate so much emotion and discussion. The image of the naked girl running away from a napalm bombed village, the word “paedo” used in tabloids to signal particular cases and reports such as the Hillsborough or the Lamy reports which brought centre stage major social issues that we dare not talk about.*

Regardless of the source, it is those media that make a cultural statement making an impact that in some cases transcends their time and forms our collective consciousness. There are numerous images, words and reports, and we choose to make some of these symbols that explain our theory of the world around us.

It was in the news that I saw a picture of a broken window, a stone and a sign next to it: “Leave my country”. The sign was held by an 11 year old refugee with big brown eyes asking why. This is not the only image that made it to the news this week; some days ago following the fatal car crash in New York the image of a 29 year old suspect from Uzbekistan appeared everywhere. These two images are of course unconnected across continents and time but there is some semiology worth noting.

We make sense of the world around us by observing. It is the media that are our eyes helping us to explore this wider world and witness relationships, events and situations that we may never considered possible. It must have been a very different world when over a century ago news of the sinking of the Titanic came through. We store images and words that help us define the way our world functions. In criminology, words are always attached to emotion and prejudice.

I deliberately chose two images: a victimised child and an adult suspect of an act of terror. They have nothing in common other than both appear foreign in the way I understand those who are not like me. Of course neither of these images is personally relatable to me but their story is compelling for different reasons. Then of course as I explore both stories and images, I wonder what is that remains of my understanding of the foreigner?

Last year, the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo produced a caricature of what would little Aylan would have done if he was to grow up, presented as a sex pest. The caricature caused public outcry but at the time, like this week, I started considering the images and their meanings. Do we put stories together based on the images we see around us? If that is a way of defining and explaining our social world then the imagery of good and bad foreigners, young and old, victims and villains may merge in a deconstruction of social reality that defines the foreigner. In that case and at that point the sign next to the 11 year old may not be voiced but it can become an implicit collective objective.

*At this stage I would like to mention that I was considering to write about the media’s “surprise” over the abuse allegations following revelations for a Hollywood producer but decide not to, due to the media’s attempt to saturate one of the most significant social issues of our times with other studies with varying levels of credibility. We observed a similar situation after the Jimmy Saville case.

A Troubling Ambiguous Order?

Sallek is a graduate from the MSc Criminology. He is currently undertaking doctoral studies at Stellenbosch University, South Africa.

Having spent the early years of my life in Nigeria, one of the first culture shock I experienced in the UK was seeing that its regular police do not wield arms. Unsurprising, in my lecture on the nature and causes of war in Africa, a young British student studying in Stellenbosch University also shared a similar but reverse sentiment – the South African police and private security forces wield arms openly. To her, this was troubling, but, even more distressing is the everyday use of most African militaries in society for internal security enforcement duties. This is either in direct conflict to the conventional understanding on the institutions involved in the criminal justice system, or African States have developed a unique and unconventional system. Thus, this raises a lot of questions needing answers and this entry is an attempt to stimulate further, thoughts and debate on this issue.

Conventionally, two spheres make up state security, the internal sphere of policing and law enforcement and the external sphere of defence and war-fighting. However, since the end of the Cold War, distinguishing between the two has become particularly difficult because of the internal involvement of the military in society. Several explanations explain why the military has become an active player in the internal sphere doing security enforcement duties in support of the police or as an independent player. Key among this is the general weakness and lack of legitimacy of the police, thus, the use of the military which has the capacity to suppress violence and ‘insurgence.’ Also, a lack of public trust, confidence, and legitimacy of the government is another key reason States resort to authoritarian practices, particularly using the military to clamp down civil society. The recent protests in Togo which turned ‘bloody’ following violent State repression presents a case in point. The recent carnage in Plateau State, Nigeria where herdsmen of similar ethnic origin as the President ‘allegedly’ killed over fifty civilians in cold blood also presents another instance. The President neither condemned the attacks nor declared a national mourning despite public outcry over the complicity of the military in the massacre.

Certainly, using the military for internal security enforcement otherwise known as military aid to civil authority in society comes with attendant challenges. One reason for this is the discrepancy of this role with its training particularly because military training and indoctrination focuses extensively on lethality and the application of force. This often results to several incidences of human rights abuses, the restriction of civil liberty and in extreme cases, summary extrajudicial killings. This situation worsens in societies affected by sectarian violence where the military assumes the leading role of law enforcement to force the return to peace as is the case in Plateau State, Nigeria. The problem with this is, in many of these States, the criminal justice system is also weak and thereby unable to guarantee judicial remedy to victims of State repression.

Consequently, citizens faced by the security dilemma of State repression and violence from armed groups may be compelled to join or seek protection from opposition groups thereby creating further security quandary. In turn, this affects the interaction of the citizenry with the military thereby straining civil-military relations in the State with the end result been the spinning of violence cycle. It also places huge economic burden with lasting impact on State resources, individuals, and corporate bodies and where the military is predatory, insecurity could worsen. The sectarian violence in Plateau State and the Niger Delta region in Nigeria where such military heavy-handedness remains the source of (in)security shows the weakness of this approach, and unless reconsidered, peace could remain elusive. Thus, now more than ever, this ambiguous (dis)order requires reconsideration for a civil approach to security in Africa.