Home » Human Rights (Page 5)

Category Archives: Human Rights

It’s never too late

‘It’s not too late to save Brexit’, Boris Johnson proclaimed in his resignation speech on Wednesday 18th July 2018. But what sort of Brexit are we really talking about? Well if you are confused, join the queue. There’s hard Brexit and soft Brexit and one might suggest every type of Brexit imaginable if it scores political points. There are calls for another referendum and a referendum on the final deal and probably a referendum on a referendum. With all the furore around Brexit it’s easy to forget what it was the British people were voting for in the first place.

As I recall, and I stand to be corrected, it was control of immigration foremost, they didn’t want any of those nasty little foreigners coming in here, taking our jobs and scrounging off the state whilst abusing the NHS. Then they didn’t want to be told what to do by Brussels and they didn’t want to be paying Brussels billions that could go into the NHS. We only had to look at increased waiting times for doctors’ appointments or the fact that we couldn’t find an NHS dentist to prove beyond doubt that immigration was out of control. Scattered in amongst this was the opportunity to be great again, masters of our own destiny and to shatter the manacles that have held us back for so long.

The rhetoric smacked of xenophobia but above all else, it aligned with historical parallels where the others are to blame for the state of a nation. The instant response of people facing difficulties is to find a scapegoat. Net migration has been a political hot potato for decades, duly made so by politicians and the media. The papers report it as if every person that comes into the country is of little value and yet people fail to look around. Who’s going to pick the crop this summer, who’s going to look after old people in nursing homes, who’s going to clean the hotel room, who’s going to do your dentistry or save your life in the operating theatre? Don’t make the mistake in thinking its British people because there aren’t enough of them that are prepared to be paid peanuts for doing menial work and not enough of them highly skilled enough to enter into medical practice.

The problem is that the ideas that so many people had about Brexit have been nurtured by politicians and newspapers alike. I rarely agree with Alister Campbell, but his comment about Paul Dacre the outgoing editor of the Daily Mail as a ‘truth-twisting, hypocritical, malign force on our culture and politics’ certainly has ring of truth to it. But its not just the papers, it wasn’t that long ago that Theresa May as Home Secretary was lambasting Europe about Human Rights legislation and the fact that she couldn’t deport Abu Hamza, a hate preacher. Anyone with a bit of savvy might have worked out that you can’t pick and choose human rights according to political whim and votes. There’s a suggestion that we could have a British Bill of Rights, a bit like Human Rights but maybe with a proviso that the government and its agencies don’t have to abide by it if they don’t fancy. A bit like Pick ‘n’ Mix, only not as sweet or tasty. Theresa May as Home Secretary promised to bring immigration down but as so much of the media hastily reported, failed to do so. Then there’s that Brexit bus proclaiming we would save billions that could go back into the NHS. What a wonderful idea except that nobody mentioned there were debts to be paid first and as every good householder and economists know, the books have to be balanced. Fanciful notions filled people’s heads, Boris and Nigel Farage are very persuasive, and president Trump thinks Boris will make a good leader. A real vote of confidence. So, what we ended up with was not so much a narrative about the benefits of staying in Europe and there are many, but a narrative about how Europe was to blame for the state of the country. Government did their job well helped along by right wing lobbyists and pseudo politicians.

And I wonder, just a little bit, whether the country would have voted as it did armed with all the facts and cognisant of all the ramifications. Boris is right, its not too late, its not too late for the government to ask the nation what it really wants, its not too late to put their hands up and say we were wrong.

Why Criminology terrifies me

Cards on the table; I love my discipline with a passion, but I also fear it. As with other social sciences, criminology has a rather dark past. As Wetzell (2000) makes clear in his book Inventing the Criminal: A History of German Criminology 1880-1945 the discipline has (perhaps inadvertently) provided the foundations for brutality and violence. In particular, the work of Cesare Lombroso was utilised by the Nazi regime because of his attempts to differentiate between the criminal and the non-criminal. Of course, Lombroso was not responsible (he died in 1909) and could not reasonably be expected to envisage the way in which his work would be used. Nevertheless, when taken in tandem with many of the criticisms thrown at Lombroso’s work over the past century or so, this experience sounds a cautionary note for all those who want to classify along the lines of good/evil. Of course, Criminology is inherently interested in criminals which makes this rather problematic on many grounds. Although, one of the earliest ideas students of Criminology are introduced to, is that crime is a social construction, which varies across time and place, this can often be forgotten in the excitement of empirical research.

My biggest fear as an academic involved in teaching has been graphically shown by events in the USA. The separation of children from their parents by border guards is heart-breaking to observe and read about. Furthermore, it reverberates uncomfortably with the historical narratives from the Nazi Holocaust. Some years ago, I visited Amsterdam’s Verzetsmuseum (The Resistance Museum), much of which has stayed with me. In particular, an observer had written of a child whose wheeled toy had upturned on the cobbled stones, an everyday occurrence for parents of young children. What was different and abhorrent in this case was a Nazi soldier shot that child dead. Of course, this is but one event, in Europe’s bloodbath from 1939-1945, but it, like many other accounts have stayed with me. Throughout my studies I have questioned what kind of person could do these things? Furthermore, this is what keeps me awake at night when it comes to teaching “apprentice” criminologists.

This fear can perhaps best be illustrated by a BBC video released this week. Entitled ‘We’re not bad guys’ this video shows American teenagers undertaking work experience with border control. The participants are articulate and enthusiastic; keen to get involved in the everyday practice of protecting what they see as theirs. It is clear that they see value in the work; not only in terms of monetary and individual success, but with a desire to provide a service to their government and fellow citizens. However, where is the individual thought? Which one of them is asking; “is this the right thing to do”? Furthermore; “is there another way of resolving these issues”? After all, many within the Hitler Youth could say the same.

For this reason alone, social justice, human rights and empathy are essential for any criminologist whether academic or practice based. Without considering these three values, all of us run the risk of doing harm. Criminology must be critical, it should never accept the status quo and should always question everything. We must bear in mind Lee’s insistence that ‘You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view. Until you climb inside of his skin and walk around in it’ (1960/2006: 36). Until we place ourselves in the shoes of those separated from their families, the Grenfell survivors , the Windrush generation and everyone else suffering untold distress we cannot even begin to understand Criminology.

Furthermore, criminologists can do no worse than to revist their childhood and Kipling’s Just So Stories:

I keep six honest serving-men

(They taught me all I knew);

Their names are What and Why and When

And How and Where and Who (1912: 83)

Bibliography

Browning, Christopher, (1992), Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland, (London: Penguin Books)

Kipling, Rudyard, (1912), Just So Stories, (New York: Doubleday Page and Company)

Lee, Harper, (1960/2006), To Kill a Mockingbird, (London: Arrow Books)

Lombroso, Cesare, (1911a), Crime, Its Causes and Remedies, tr. from the Italian by Henry P. Horton, (Boston: Little Brown and Co.)

-, (1911b), Criminal Man: According to the Classification of Cesare Lombroso, Briefly Summarised by His Daughter Gina Lombroso Ferrero, (London: G. P. Putnam’s Sons)

-, (1876/1878/1884/1889/1896-7/ 2006), Criminal Man, tr. from the Italian by Mary Gibson and Nicole Hahn Rafter, (London: Duke University Press)

Solway, Richard A., (1982), ‘Counting the Degenerates: The Statistics of Race Deterioration in Edwardian England,’ Journal of Contemporary History, 17, 1: 137-64

Wetzell, Richard F., (2000), Inventing the Criminal: A History of German Criminology 1880-1945, (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press)

(In)Human Rights in the “Compliant Environment”

In the aftermath of the Windrush generation debacle being brought into the light, Amber Rudd resigned, and a new Home Secretary was appointed. This was hailed by the government as a turning point, an opportunity to draw a line in the sand. Certainly, within hours of his appointment, Sajid Javid announced that he ‘would do right by the Windrush generation’. Furthermore, he insisted that he did not ‘like the phrase hostile’, adding that ‘the terminology is incorrect’ and that the term itself, was ‘unhelpful’. In its place, Javid offered a new term, that of; ‘a compliant environment’. At first glance, the language appears neutral and far less threatening, however, you do not need to dig too deep to read the threat contained within.

According to the Oxford Dictionary (2018) the definition of compliant indicates a disposition ‘to agree with others or obey rules, especially to an excessive degree; acquiescent’. Compliance implies obeying orders, keeping your mouth shut and tolerating whatever follows. It offers, no space for discussion, debate or dissent and is far more reflective of the military environment, than civilian life. Furthermore, how does a narrative of compliance fit in with a twenty-first century (supposedly) democratic society?

The Windrush shambles demonstrates quite clearly a blatant disregard for British citizens and implicit, if not, downright aggression. Government ministers, civil servants, immigration officers, NHS workers, as well as those in education and other organisations/industries, all complying with rules and regulations, together with pressures to exceed targets, meant that any semblance of humanity is left behind. The strategy of creating a hostile environment could only ever result in misery for those subjected to the State’s machinations. Whilst, there may be concerns around people living in the country without the official right to stay, these people are fully aware of their uncertain status and are thus unlikely to be highly visible. As we’ve seen many times within the CJS, where there are targets that “must” be met, individuals and agencies will tend to go for the low-hanging fruit. In the case of immigration, this made the Windrush generation incredibly vulnerable; whether they wanted to travel to their country of origin to visit ill or dying relatives, change employment or if they needed to call on the services of the NHS. Although attention has now been drawn to the plight of many of the Windrush generation facing varying levels of discrimination, we can never really know for sure how many individuals and families have been impacted. The only narratives we will hear are those who are able to make their voices heard either independently or through the support of MPs (such as David Lammy) and the media. Hopefully, these voices will continue to be raised and new ones added, in order that all may receive justice; rather than an off-the-cuff apology.

However, what of Javid’s new ‘compliant environment’? I would argue that even in this new, supposedly less aggressive environment, individuals such as Sonia Williams, Glenda Caesar and Michael Braithwaite would still be faced with the same impossible situation. By speaking out, these British women and man, as well as countless others, demonstrate anything but compliance and that can only be a positive for a humane and empathetic society.

Oh, just f*** off.

A strange title to give to a blog but, one that expresses my feelings every time I turn the television and watch politicians procrastinating about a major issue. How else do I try and express my utter contempt for the leaders of this country that cause chaos and misery and yet take no responsibility for what they have done.

I watch Donald Trump on television and I’m simply given to thinking ‘You’re an idiot’, I appreciate that others may have stronger words, particularly some immigrants, legal or illegal, in the United States. I will draw parallels with his approach later, how could I not, given the Empire Windrush disgrace.

A week or so ago a significant topic on the news was the gender pay gap. The Prime Minister Theresa May was all over this one, after all it is the fault of corporations and businesses the pay gap exists. No responsibility there then but votes to be had.

Within the same news bulletin, there was an interview with a teacher who explained how teachers were regularly taking children’s clothes home to wash them as the family couldn’t afford to do so. Children were appearing at school and the only meal they might have for the day was the school meal. Now that might seem terrible in a third world country but he wasn’t talking about a third world country he was talking about England. Surprisingly, the prime minister was not all over that one, no votes to be had.

Within the same time frame there were more deaths in London due to gang crime. The Prime Minister and the Home Secretary Amber Rudd were all over that one, well of sorts, but then it is a political hot potato. The police and the community need to do more, an action plan is produced.

Then we have the Windrush debacle, tragedy and disgrace. The Home Secretary eventually said she was sorry and blamed the civil servants in the Home Office. They had become inhuman, clearly not her fault. The Prime Minister said sorry, it was under her watch at the Home Office that the first seeds of this disaster were plotted and then hatched, clearly though not her fault either. Got the right wing votes but seem to have lost a few others along the way.

What ties all of these things together; class structure, inequality and poverty and an unwillingness in government to address these, not really a vote winner. The gender pay gap is someone else’s fault and even if addressed, won’t deal with the inequalities at the bottom of the pay structure. Those women on zero hour contracts and minimum wages won’t see the benefit, only those in middle or higher ranking jobs. Votes from some but not from others, a gain rather than any loss.

The fact that children exist in such poverty in this country that teachers have to intervene and take on welfare responsibilities is conveniently ignored. As is the fact that much of the violence that plagues the inner city streets happens to occur in poor neighbourhoods where social and economic deprivation is rife. The Windrush issue is just another example of right wing rhetoric leading to right wing action that impacts most on the vulnerable.

When the gender pay gap hit the news there was a senior figure from a company that appeared in the news. He said that addressing the gender pay gap by having more women in higher positions in his company was good for the company, good for the country, and good for the economy.

Judging from the example given by the country’s senior management, I have to say I am far from convinced. And yes as far as I’m concerned, when they open their mouths and pontificate, they can just f*** off.

‘I read the news today, oh boy’

The English army had just won the war

The English army had just won the war

A crowd of people turned away

But I just had to look

Having read the book

(Lennon and McCartney, 1967),

The news these days, without fail, is terrible. Wherever you look you are confronted by misery, death, destruction and terror. Regular news channels and social media bombard us with increasingly horrific tales of people living and dying under tremendous pressure, both here in the UK and elsewhere in the world. Below are just a couple of examples drawn from the mainstream media over the space of a few days, each one an example of individual or collective misery. None of them are unique and they all made the headlines in the UK.

‘Deaths of UK homeless people more than double in five years’

‘Syria: 500 Douma patients had chemical attack symptoms, reports say’

‘London 2018 BLOODBATH: Capital on a knife edge as killings SOAR to 56 in three months’

So how do we make sense of these tumultuous times? Do we turn our backs and pretend it has nothing to do with us? Can we, as Criminologists, ignore such events and say they are for other people to think about, discuss and resolve?

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, Stanley Cohen, posed a similar question; ‘How will we react to the atrocities and suffering that lie ahead?’ (2001: 287). Certainly his text States Of Denial: Knowing about Atrocities and Suffering makes clear that each of us has a part to play, firstly by ‘knowing’ that these things happen; in essence, bearing witness and acknowledging the harm inherent in such atrocities. But is this enough?

Cohen, persuasively argues, that our understanding has fundamentally changed:

The political changes of the last decade have radically altered how these issues are framed. The cold-war is over, ordinary “war” does not mean what it used to mean, nor do the terms “nationalism”, “socialism”, “welfare state”, “public order”, “security”, “victim”, “peace-keeping” and “intervention” (2001: 287).

With this in mind, shouldn’t our responses as a society, also have changed, adapted to these new discourses? I would argue, that there is very little evidence to show that this has happened; whilst problems are seemingly framed in different ways, society’s response continues to be overtly punitive. Certainly, the following responses are well rehearsed;

- “move the homeless on”

- “bomb Syria into submission”

- “increase stop and search”

- “longer/harsher prison sentences”

- “it’s your own fault for not having the correct papers?”

Of course, none of the above are new “solutions”. It is well documented throughout much of history, that moving social problems (or as we should acknowledge, people) along, just ensures that the situation continues, after all everyone needs somewhere just to be. Likewise, we have the recent experiences of invading Iraq and Afghanistan to show us (if we didn’t already know from Britain’s experiences during WWII) that you cannot bomb either people or states into submission. As criminologists, we know, only too well, the horrific impact of stop and search, incarceration and banishment and exile, on individuals, families and communities, but it seems, as a society, we do not learn from these experiences.

Yet if we were to imagine, those particular social problems in our own relationships, friendship groups, neighbourhoods and communities, would our responses be the same? Wouldn’t responses be more conciliatory, more empathetic, more helpful, more hopeful and more focused on solving problems, rather than exacerbating the situation?

Next time you read one of these news stories, ask yourself, if it was me or someone important to me that this was happening to, what would I do, how would I resolve the situation, would I be quite so punitive? Until then….

Whoever fights monsters should see to it that in the process he does not become a monster. And when you look long into an abyss, the abyss also looks into you (Nietzsche, 1886/2003: 146)

References:

Cohen, Stanley, (2001), States Of Denial: Knowing about Atrocities and Suffering, (Cambridge: Polity Press)

Lennon, John and McCartney, Paul, (1967), A Day in the Life, [LP]. Recorded by The Beatles in Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, EMI Studios: Parlaphone

Nietzsche, Friedrich, (1886/2003), Beyond Good and Evil: Prelude to a Philosophy of the Future, tr. from the German by R. J. Hollingdale, (London: Penguin Books)

You know what really grinds my gears…

Jessica is an Associate Lecturer teaching modules in the first year.

Unlike the episode from Family Guy, which sees the main character Peter Griffin present a segment on the Quahog news regarding perhaps ‘trivial’ issues which really grind his gears, I would hope that what grinds my gears is also irritating and frustrating for others.

What really grinds my gears is the portrayal of women without children being pitied in the media. Take a recent example of Jennifer Aniston who has (relatively recently) split from her partner. The coverage appears to be (and this is just my interpretation) very pitiful around how Jennifer does not have any children; and this is a shame. Is it? Has anyone bothered to ask Jennifer if she feels this is a shame? Is this something Jennifer feels is missing from her life? Who knows: It might be the case. But the issue that I have, and ultimately what really grinds my gears, is this assumption that as a woman you are expected to want and to eventually have children.

There are lots of arguments around how society is making progress (I’ll leave it amongst yourselves to argue if this is accurate or not, and if so to what extent), however is it in this context? If women are still pressured by the media, family and friends to conform to the gendered stereotype of women as mothers, has society made progress? I am not for one minute saying that women shouldn’t be mothers, or that all women should be mothers; what I am annoyed about is this apparent assumption that all women want to be mothers and more harmful, the ignorant assumption that all women can be mothers.

It really grinds my gears that it still appears to be the case that women are not ‘doing gender’ correctly if they are not mothers, or if they do not want to be mothers. Families and friends seem to assume that having a family is what everyone wants and strives to achieve, therefore not doing this results in some form of failure. How is this fair? The human body is complex (not that I have any real knowledge in this area), imagine the impact you are having on women assuming they want and will have a family, if biologically, and potentially financially, having one is difficult for them to do? Is it not rude that you are assuming that women want children because their biology allows them the potential to have them?

In answer to the last question: Yes! I think it is rude, wrong and ultimately irritating that it is assumed that all women want children and them not having them somehow means their life has missed something. As with all lifestyle choices and decisions, not every lifestyle is for everyone. Therefore I would greatly appreciate it if society acknowledged that women not wanting or having children does not mean that they have accomplished less in life in comparison to those who have children, it just means they have made different choices and walked different paths.

For me, this just highlights how far we still have to go to eradicate gender stereotypes; that is, if we even can?

A Failing Cultural or Criminal Justice System?

Sallek is a graduate from the MSc Criminology. He is currently undertaking doctoral studies at Stellenbosch University, South Africa.

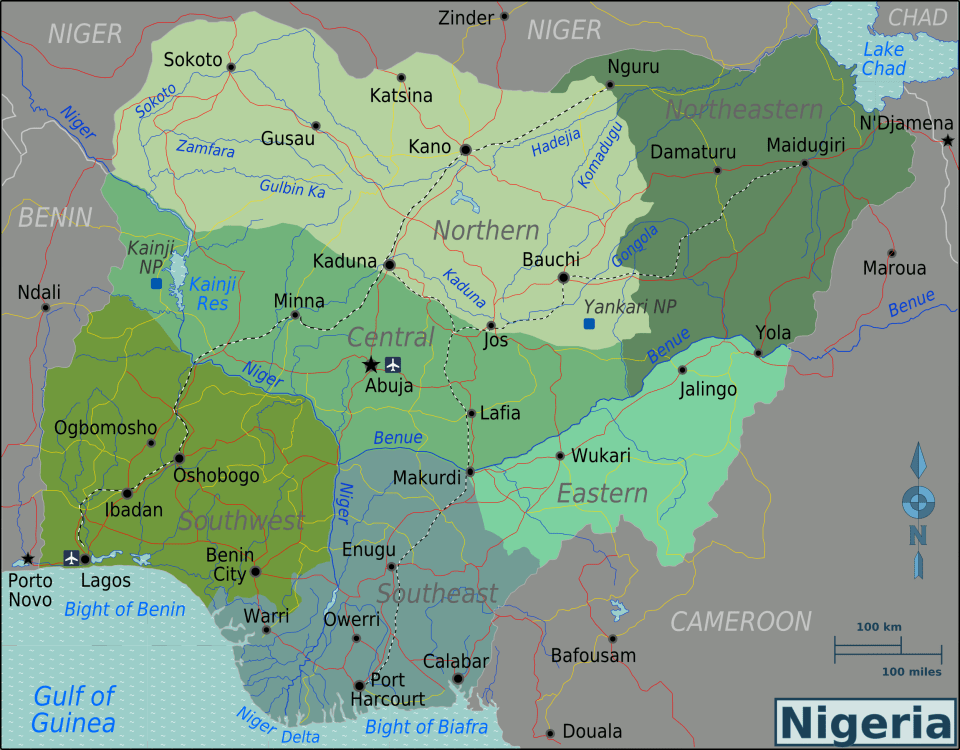

In this piece, I reflect on the criminal justice system in Nigeria showing how a cultural practice evoked a social problematique, one that has exposed the state of the criminal justice system of the country. While I dissociate myself from the sect, I assume the place of the first person in contextualizing this discourse.

In line with the norm, our mothers were married to them. Having paid the bride wealth, even though they have no means, no investment and had little for their upkeep, they married as many as they could satisfy. In our number, they birth as many as their strength could allow, but, little did we know the intention is to give us out to tutelage from religious teachers once we could speak. So, we grew with little or no parental care, had little or no contact, and the street was to become our home where we learnt to be tough and strong. There we learnt we are the Almajiri (homeless children), learning and following the way and teaching of a teacher while we survived on alms and the goodwill of the rich and the sympathetic public.

As we grew older, some learnt trades, others grew stronger in the streets that became our home, a place which toughened and strengthened us into becoming readily available handymen, although our speciality was undefined. We became a political tool servicing the needs of desperate politicians, but, when our greed and their greed became insatiable, they lost their grip on us. We became swayed by extremist teachings, the ideologies were appealing and to us, a worthy course, so, we joined the sect and began a movement that would later become globally infamous. We grew in strength and might, then they coerced us into violence when in cold blood, their police murdered our leader with impunity. No one was held responsible; the court did nothing, and no form of judicial remedy was provided. So, we promised full scale war and to achieve this, we withdrew, strategized, and trained to be surgical and deadly.

The havoc we created was unimaginable, so they labelled us terrorists and we lived the name, overwhelmed their police, seized control of their territories, and continued to execute full war of terror. We caused a great humanitarian crisis, displaced many, and forced a refugee crisis, but, their predicament is better than our childhood experience. So, when they sheltered these displaced people in camps promising them protection, we defiled this fortress and have continued to kill many before their eyes. The war they waged on us using their potent monster, the military continuous to be futile. They lied to their populace that they have overpowered us, but, not only did we dare them, we also gave the military a great blow that no one could have imagined we could. The politicians promised change, but we proved that it was a mere propaganda when they had to negotiate the release of their daughters for a ransom which included releasing our friends in their custody. After this, we abducted even more girls at Dapchi. Now I wonder, these monsters we have become, is it our making, the fault of our parents, a failure of the criminal justice system, or a product of society?

About a year ago, as a team we started this blog in order to relate criminological ideas into everyday life. News, events and markers on our social calendar became sources of inspiration and inquiry. Within a year, we have managed somehow to reflect on the academic cycle, some pretty heavy social issues that evoked our passions and interests. Those of you who read our entries, thank you for taking the time, especially those who left comments with your own experiences and ideas.

About a year ago, as a team we started this blog in order to relate criminological ideas into everyday life. News, events and markers on our social calendar became sources of inspiration and inquiry. Within a year, we have managed somehow to reflect on the academic cycle, some pretty heavy social issues that evoked our passions and interests. Those of you who read our entries, thank you for taking the time, especially those who left comments with your own experiences and ideas.