Home » freedom (Page 3)

Category Archives: freedom

‘Guilty’ of Coming Out Daily – Abroad. #BlackenAsiaWithLove

I am annoyed that our apartment-building manager told my husband that a two-bedroom had recently become available, and that we should move in because we would be “more comfortable.” My husband always takes such statements at face value, then performs his own cost/benefits analysis. Did the manager offer a discount, I asked? I mean, if he’s genuinely concerned about our comfort, shouldn’t he put his money where his mouth is? That’s probably just the American in me talking: He was either upselling the property or probing us to see what the deal was – not at all concerned about our comfort. I speak code, too.

The most homophobic thing that anyone has ever said to me is not any slur, but that gay people should not “flaunt it.” As if concealing our identities would magically erase homophobia. This reveals that the speaker either doesn’t know – or doesn’t care to know – how readily people everywhere speak about our personal lives. There are random people I have met in every single part of the world, that ask my marital status. It comes shortly after asking my name and where I’m from. The words used are revealing – just ask any divorced person who has engaged with any society’s traditions. Is it deceptive to say that they are “single,” instead? What’s more, regardless of language, preferred terms like “unmarried” reveal the value conferred upon this status. You’re not a whole person until you’re married, and a parent. It is only then that one is genuinely conferred what we sociologists call ‘personhood’. Also, are married lesbians called two Mrs.?

Come out, come out wherever you are.

In many parts of the world, being ‘out’ carries the death penalty, including parts of my father’s homeland, Nigeria. I’ve literally avoided visiting Nigeria because of the media-fueled fear of coming out. I hate the distance it’s wedged between my people, our culture and I. There was a time when coming out was literally the hardest thing I ever had to do. Now, l must come out daily.

Back in the UK, many educators would like to believe that they don’t discuss their personal lives with students. But who hasn’t been casually asked how one spent the weekend? Do I not say “My husband and I…” just as anyone else might? Abroad, do I correct co-workers when they refer to us as ‘friends’? Yesterday, I attended an academic conference. All the usual small talk. I came out a dozen times by lunch.

In teaching English here in Asia, isn’t it unfair for me to conceal from my students the gender of my “life-partner,” which is actually our formal legal status? Am I politicising my classroom by simply teaching gender-neutral terms like ‘spouse’ or ‘partner’? Or, do I simply use the term ‘husband’ and skim over their baffled faces as they try to figure out if they have understood me properly? Am I denying them the opportunity to prepare for the sought-after life in the west? Further, what about the inevitability of that one ‘questioning’ student in my classroom searching for signs of their existence!

I was recently cornered in the hallway by the choreographer hired by our department to support our contribution to the university’s staff talent competition (see picture below*). She spoke with me in German, explaining that she’d lived several years in the former GDR. There are many Vietnamese who’d been ‘repatriated’ from the GDR upon reunification. So, given the historical ties to Communism, it’s commonplace to meet German (and Russian) speakers here. Naturally, folks ask how/why I speak (basic) German. My spouse of seventeen years is German, so it’d be weird if I hadn’t picked up any of the language. It’s really deceptive to conceal gender in German, which has three. I speak German almost every day here in Hanoi.

The word is ‘out’.

In Delhi, we lived in the same 2-bedroom flat for over 7 years. It became clear to our landlady very early on that we slept in one bedroom. Neighbours, we’re told, also noticed that we only ever had one vehicle between us and went most places together. Neither the landlady nor any neighbour ever confronted us, so we never had to formally come out. Yet, the chatter always got back to us.

As a Peace Corps volunteer in rural Mali in the late 90’s, I learned to speak Bambara. Bambara greetings are quite intimate: One normally asks about spouses, parents and/or children, just as Black-Americans traditionally would say “How yo’ momma doin?’” In Mali, village people make it their business to get single folks hitched. Between the Americans, then, it became commonplace to fake a spouse, just so one would be left in peace. Some women wore wedding bands for added protection, as a single woman living alone was unconscionable. The official advice for gays was to stay closeted L. While I pretended to be the husband of several volunteers, I could never really get the gist of it in my village. Besides, at 23 years old, being a single man wasn’t as damning as it is for women. I only needed excuses to reject the young women villagers presented to me. Anyhow, as soon as city migrants poured back to the village for Ramadan, I quickly discovered that there are plenty of LGBTQ+ folks in Mali! This was decades before Grindr.

Here in Hanoi, guys regularly, casually make gestures serving up females, as if to say: ‘Look, she’s available, have her’. I’ve never bothered to learn the expected response, nor paid enough attention to how straight men handle such scenarios. Recently, as we left a local beer hall with another (gay) couple, one waiter rather cheekily made such gestures at a hostess. In response, I made the same gestures towards him; he then served himself up as if to say ‘OK’. That’s what’s different about NOW as opposed to any earlier period: Millennials everywhere are aware of gay people.

A group of lads I sat with recently at a local tea stall made the same gestures to the one girl in their group. After coming out, the main instigator seamlessly gestured towards the most handsome in his clique. When I press Nigerian youth about the issue, the response is often the same: We don’t have a problem with gay people, we know gay people, it’s the old folk’s problem. Our building manager may be such a relic.

*Picture from The 2019 Traditional Arts Festival at Hanoi University of Science and Technology (HUST)

A month of Black history through the eyes of a white, privileged man… an open letter

Dear friends,

Over the years, in my line of work, there was a conviction, that logic as the prevailing force allows us to see social situations around (im)passionately, impartially and fairly. Principles most important especially for anyone who dwells in social sciences. We were “raised” on the ideologies that promote inclusivity, justice and solidarity. As a kid, I remember when we marched as a family against nuclear proliferation, and later as an adult I marched and protested for civil rights on the basis of sexuality, nationality and class. I took part in anti-war marches and protested and took part in strikes when fees were introduced in higher education.

All of these were based on one very strongly, deeply ingrained, view that whilst the world may be unfair, we can change it, rebel against injustices and make it better. A romantic view/vision of the world that rests on a very basic principle “we are all human” and our humanity is the home of our unity and strength. Take the environment for example, it is becoming obvious to most of us that this is a global issue that requires all of us to get involved. The opt-out option may not be feasible if the environment becomes too hostile and decreases the habitable parts of the planet to an ever-growing population.

As constant learners, according to Solon (Γηράσκω αεί διδασκόμενος)[1] it is important to introspect views such as those presented earlier and consider how successfully they are represented. Recently I was fortunate to meet one of my former students (@wadzanain7) who came to visit and talk about their current job. It is always welcome to see former students coming back, even more so when they come in a reflective mood at the same time as Black history month. Every year, this is becoming a staple in my professional diary, as it is an opportunity to be educated in the history that was not spoken or taught at school.

This year’s discussions and the former student’s reflections made it very clear to me that my idealism, however well intended, is part of an experience that is deeply steeped in white men’s privilege. It made me question what an appropriate response to a continuous injustice is. I was aware of the quote “all that is required for evil to triumph is for good men to do nothing” growing up, part of my family’s narrative of getting involved in the resistance, but am I true to its spirit? To understand there is a problem but do nothing about it, means that ultimately you become part of the same problem you identify. Perhaps in some regards a considered person is even worse because they see the problem, read the situation and can offer words of solace, but not discernible actions. A light touch liberalism, that is nice and inclusive, but sits quietly observing history written in the way as before, follow the same social discourses, but does nothing to change the problems. Suddenly it became clear how wrong I am. A great need to offer a profound apology for my inaction and implicit collaboration to the harm caused.

I was recently challenged in a discussion about whether people who do not have direct experience are entitled to a view. Do those who experience racism voice it? Of course, the answer is no; we can read it, stand against it, but if we have not experienced it, maybe, just maybe, we need to shut up and let other voices be heard and tell their stories. Black history month is the time to walk a mile in another person’s shoes.

Sincerely yours

M

[1] A very rough translation: I learn, whilst I grow, life-long learning.

A Love Letter: in praise of art

Some time ago, I wrote ‘A Love Letter: in praise of poetry‘, making the case as to why this literary form is important to understanding the lived experience. This time, I intend to do similar in relation to visual art.

Tomorrow, I’m plan to make my annual visit to the Koestler Arts’ Exhibition on show at London’s Southbank Centre. This year’s exhibition is entitled Another Me and is curated by the musician, Soweto Kinch. Previous exhibitions have been curated by Benjamin Zephaniah, Antony Gormley and prisoners’ families. Each of the exhibitions contain a diverse range of unique pieces, displaying the sheer range of artistic endeavours from sculpture, to pastels and from music to embroidery. This annual exhibition has an obvious link to criminology, all submissions are from incarcerated people. However, art, regardless of medium, has lots of interest to criminologists and many other scholars.

I have never formally studied art, my reactions and interpretations are entirely personal. I reason that the skills inherent in criminological critique and analysis are applicable, whatever the context or medium. The picture above shows 4 of my favourite pieces of art (there are many others). Each of these, in their own unique way, allow me to explore the world in which we all live. For me, each illustrate aspects of social (in)justice, social harms, institutional violence and the fight for human rights. You may dislike my choices. arguing that graffiti (Banksy) and photography (Mona Hatoum) have no place within art proper. You may disagree with my interpretation of these pieces, dismissing them as pure ephemera, forgotten as quickly as they are seen and that is the beauty of discourse.

Nonetheless, for me they capture the quintessential essence of criminology. It is a positive discipline, focused on what “ought” to be, rather than what is. To stand small, in front of Picasso’s (1937) enormous canvas Guernica allows for consideration of the sheer scale of destruction, inherent in mechanised warfare. Likewise, Banksy’s (2005) The Kissing Coppers provides an interesting juxtaposition of the upholders of the law behaving in such a way that their predecessors would have persecuted them. Each of the art pieces I have selected show that over time and space, the behaviours remain the same, the only change, the level of approbation applied from without.

Art galleries and museums can appear terrifying places, open only to a select few. Those that understand the rules of art, those who make the right noises, those that have the language to describe what they see. This is a fallacy, art belongs to all of us. If you don’t believe me, take a trip to the Southbank Centre very soon. It’s not scary, nobody will ask you questions, everyone is just there to see the art. Who knows you might just find something that calls out to you and helps to spark your criminological imagination. You’ll have to hurry though…closes 3 November, don’t miss out!

The tyranny of populism

Himmler (1943)

So, we have a new prime minister Boris Johnson. Donald Trump has given his endorsement, hardly surprising, and yet rather than having a feeling of optimism that Boris in his inaugural speech in the House of Commons wished to engender amongst the population, his appointment fills me with dread. Judging from reactions around the country, I’m not the only one, but people voted for him just the same as people voted for Donald Trump and Volodymyr Zelensky, the recently elected Ukrainian president.

The reasons for their success lie not in a proven ability to do the job but in notions of popularity reinforced by predominantly right-wing rhetoric. Of real concern, is this rise of right wing populism across Europe and in the United States. References to ‘letter boxes’ (Johnson, 2018), degrading Muslim women or tweeting ethnic minority political opponents to ‘go back to where they came from’ (Lucas, 2019) seems to cause nothing more than a ripple amongst the general population and such rhetoric is slowly but surely becoming the lingua franca of the new face of politics. My dread is how long before we hear similar chants to ‘Alle Juden Raus!’ (1990), familiar in 1930s Nazi Germany?

It seems that such politics relies on the ability to appeal to public sentiment around nationalism and public fears around the ‘other’. The ‘other’ is the unknown in the shadows, people who we do not know but are in some way different. It is not the doctors and nurses, the care workers, those that work in the hospitality industry or that deliver my Amazon orders. These are people that are different by virtue of race or colour or creed or language or nationality and, yet we are familiar with them. It is not those, it is not the ‘decent Jew’ (Himmler, 1943), it is the people like that, it is the rest of them, it is the ‘other’ that we need to fear.

The problems with such popular rhetoric is that it does not deal with the real issues, it is not what the country needs. John Stuart Mill (1863) was very careful to point out the dangers that lie within the tyranny of the majority. The now former prime minister Theresa May made a point of stating that she was acting in the national Interest (New Statesman, 2019). But what is the national interest, how is it best served? As with my university students, it is not always about what people want but what they need. I could be very popular by giving my students what they want. The answers to the exam paper, the perfect plan for their essay, providing a verbal precis of a journal article or book chapter, constantly reminding them when assignments are due, turning a blind eye to plagiarism and collusion*. This may be what they want, but what they need is to learn to be independent, revise for an exam, plan their own essays, read their own journal articles and books, plan their own assignment hand in dates, and understand and acknowledge that cheating has consequences. What students want has not been thought through, what students need, has. What students want leads them nowhere, hopefully what students need provides them with the skills and mindset to be successful in life.

What the population wants has not been thought through, the ‘other’ never really exists and ‘empire’ has long gone. What the country needs should be well thought out and considered, but being popular seems to be more important than delivering. Being liked requires little substance, doing the job is a whole different matter.

*I am of course generalising and recognise that the more discerning students recognise what they need, albeit that sometimes they may want an easier route through their studies.

Alle Juden Raus (1990) ‘All Jews Out’, Directed by Emanuel Rund. IMDB

Himmler, H. (1943) Speech made at Posen on October 4, 1943, U.S. National Archives, [online] available at http://www.historyplace.com/worldwar2/holocaust/h-posen.htm [accessed 26 July 2019].

Johnson, B. (2018) Denmark has got it wrong. Yes, the burka is oppressive and ridiculous – but that’s still no reason to ban it, The Telegraph, 5th August 2018.

Lucas, A. (2019) Trump tells progressive congresswomen to ‘go back’ to where they came from, CNBC 14 July 2019 [online] available at https://www.cnbc.com/2019/07/14/trump-tells-progressive-congresswomen-to-go-back-to-where-they-came-from.html [accessed 26 July 2019]

Mill, J. S. (1863) On Liberty, [online] London: Tickner and Fields, Available from https://play.google.com/store/books [accessed 26 July 2019]

New Statesman (2019) Why those who say they are acting in “the national interest” often aren’t, [online] Available at https://www.newstatesman.com/politics/uk/2019/01/why-those-who-say-they-are-acting-national-interest-often-arent [accessed 26 July 2019]

Forgotten

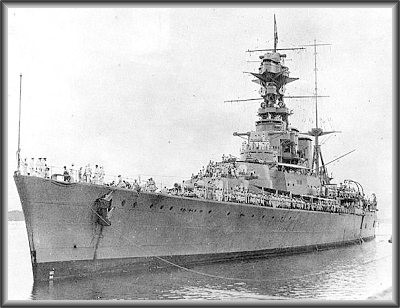

It is now nearly two weeks since Remembrance Day and reading Paula’s blog. Whilst understanding and agreeing with much of the sentiment of the blog, I must confess I have been somewhat torn between the critical viewpoint presented and the narrative that we owe the very freedoms we enjoy to those that served in the second world war. When I say served, I don’t necessarily mean those just in the armed services, but all the people involved in the war effort. The reason for the war doesn’t need to be rehearsed here nor do the atrocities committed but it doesn’t hurt to reflect on the sacrifices made by those involved.

My grandad, now deceased, joined the Royal Navy as a 16-year-old in the early 1930s. It was a job and an opportunity to see the world, war was not something he thought about, little was he to know that a few years after that he would be at the forefront of the conflict. He rarely talked about the war, there were few if any good memories, only memories of carnage, fear, death and loss. He was posted as missing in action and found some 6 months later in hospital in Ireland, he’d been found floating around in the Irish Sea. I never did find out how this came about. He had feelings of guilt resultant of watching a ship he was supposed to have been on, go down with all hands, many of them his friends. Fate decreed that he was late for duty and had to embark on the next ship leaving port. He described the bitter cold of the Artic runs and the Kamikaze nightmare where planes suddenly dived indiscriminately onto ships, with devastating effect. He had half of his stomach removed because of injury which had a major impact on his health throughout the rest of his life. He once described to me how the whole thing was dehumanised, he was injured so of no use, until he was fit again. He was just a number, to be posted on one ship or another. He swerved on numerous ships throughout the war. He had medals, and even one for bravery, where he battled in a blazing engine room to pull out his shipmates. When he died I found the medals in the garden shed, no pride of place in the house, nothing glorious or romantic about war. And yet as he would say, he was one of the lucky ones.

My grandad and many like him are responsible for my resolution that I will always use my vote. I do this in the knowledge that the freedom to be able to continue to vote in any way I like was hard won. I’m not sure that my grandad really thought that he was fighting for any freedom, he was just part of the war effort to defeat the Nazis. But it is the idea that people made sacrifices in the war so that we could enjoy the freedoms that we have that is a somewhat romantic notion that I have held onto. Alongside this is the idea that the war effort and the sacrifices made set Britain aside, declaring that we would stand up for democracy, freedom and human rights.

But as I juxtapose these romantic notions against reality, I begin to wonder what the purpose of the conflict was. Instead of standing up for freedom and human rights, our ‘Great Britain’ is prepared to get into bed with and do business with the worst despots in the world. Happy to do business with China, even though they incarcerate up to a million people such as the Uygurs and other Muslims in so called ‘re-education camps’, bend over backwards to climb into bed with the United States of America even though the president is happy to espouse the shooting of unarmed migrating civilians and conveniently play down or ignore Saudi Arabia’s desolation of the Yemini people and murder of political opponents.

In the clamber to reinforce and maintain nationalistic interests and gain political advantage our government and many like it in the west have forgotten why the war time sacrifices were made. Remembrance should not just be about those that died or sacrificed so much, it should be a time to reflect on why.

Are we really free?

This year the American Society of Criminology conference (Theme: Institutions, Cultures and Crime) is in Atlanta, GA a city famous for a number of things; Mitchell’s novel, (1936), Gone with the Wind and the home of both Coca-Cola, and CNN. More importantly the city is the birthplace and sometime home of Dr Martin Luther King Jr and played a pivotal role in the Civil Rights Movement. Throughout the city there are reminders of King’s legacy, from street names to schools and of course, The King Center for Non-Violent Social Change.

This week @manosdaskalou and I visited the Center for Civil and Human Rights, opened in 2014 with the aim of connecting the American Civil Rights Movement, to broader global claims for Human Rights. A venue like this is an obvious draw for criminologists, keen to explore these issues from an international perspective. Furthermore, such museums engender debate and discussion around complex questions; such as what it means to be free; individually and collectively, can a country be described as free and why individuals and societies commit atrocities.

According to a large-scale map housed within the Center the world is divided up into countries which are free, partially free and not free. The USA, the UK and large swathes of what we would recognise as the western world are designated free. Other countries such as Turkey and Bolivia are classified as partially free, whilst Russia and Nigeria are not free. Poor Tonga receives no classification at all. This all looks very scientific and makes for a graphic illustration of areas of the world deemed problematic, but by who or what? There is no information explaining how different countries were categorised or the criteria upon which decisions were made. Even more striking in the next gallery is a verbatim quotation from Walter Cronkite (journalist, 1916-2009) which insists that ‘There is no such thing as a little freedom. Either you are all free, or you are not free.’ Unfortunately, these wise words do not appear to have been heeded when preparing the map.

Similarly, another gallery is divided into offenders and victims. In the first half is a police line-up containing a number of dictators, including Hitler, Pol Pot and Idi Amin suggesting that bad things can only happen in dictatorships. But what about genocide in Rwanda (just one example), where there is no obvious “bad guy” on which to pin blame? In the other half are interactive panels devoted to individuals chosen on the grounds of their characteristics (perceived or otherwise). By selecting characteristics such LGBT, female, migrant or refugee, visitors can read the narratives of individuals who have been subjected to such regimes. This idea is predicated on expanding human empathy, by reading these narratives we can understand that these people aren’t so different to us.

Museums such as the Center for Civil and Human Rights pose many more questions than they can answer. Their very presence demonstrates the importance of understanding these complex questions, whilst the displays and exhibits demonstrate a worldview, which visitors may or may not accept. More importantly, these provide a starting point, a nudge toward a dialogue which is empathetic and (potentially) focused toward social justice. As long as visitors recognise that nudge long after they have left the Center, taking the ideas and arguments further, through reading, thinking and discussion, there is much to be hopeful about.

In the words of Martin Luther King Jr (in his 1963, Letter from Birmingham Jail):

‘Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly’