Home » Civil Liberty (Page 2)

Category Archives: Civil Liberty

When the Police takes to Tweeter HashTags to Seek ‘Justice’

https://twitter.com/PoliceNG/status/1159548411244371969?s=20)

I am tempted to end this blog in one sentence with the famous Disney lyrics, “disaster is in the air” but this may do no justice to the entry as it lacks a contextual background. So last week, Nigerian Twitter was agog with numerous tweets, retweets, comments, and reactions following the news that soldiers of the Nigerian Army had allegedly killed one civilian and three police personnel in the line of duty. A brief summary of the case is that the killed police personnel had arrested an alleged notorious and ‘wanted’ kidnaper and were transporting him to a command headquarters when they ran into a military checkpoint. Soldiers at the checkpoint allegedly opened fire at close range, killed the police who were said to have attempted identifying themselves, and freed the handcuffed ‘kidnapper.’

In a swift reaction, a Joint Investigation Panel comprised of the Police and the Army was constituted to investigate the incident. Notwithstanding this, the Police took to their Twitter handle @PoliceNG calling out for justice and expressing dissatisfaction and concerns in what metamorphosed into series of threads and hashtags – #WhereIsEspiritDCorp and #ProvideAnswersNigerianArmy. Ordinarily, this should have aroused and generated wide condemnation and national mourning, but, the comments, tweets and reactions on twitter suggests otherwise. While Nigerians expressed sympathy to the victims of the unfortunate incident, they also took to the social media platform to unravel their anger with many unleashing unsympathetic words and re-stating their distrust in the Police. In fact, it was the strong opinion of many that the incident was just a taste of their medicine as they often infringe on the rights of civilians daily, and are notoriously stubborn and predatory.

Certainly, this issue has some criminological relevance and one is that it brings to light the widely debated conversation on the appropriateness and the potency of deploying the military in society for law enforcement duties which they are generally not trained to do. Hence, this evokes numerous challenges including the tendency for it to make civilians loathe to interact with the military. I have previously argued that the internal use of the Nigerian military in law enforcement duties has exacerbated rather than ameliorated insecurity in several parts of the country. As with this instance, this is due to the penchant of the military to use force, the unprofessional conduct of personnel, and a weak system of civil control of the military to hold personnel accountable for their actions.

Similarly, this issue has also raised concerns on the coordination of the security forces and the need for an active operational command which shares security information with all the agencies involved in internal security. However, the reality is that interagency feud among the numerous Nigerian security agencies remains a worrying concern that not only undermine, but hinders the likelihood for an effective coordination of security activities.

Another angle to the conversation is that the social media provides a potent weapon for citizens to compel response and actions from state authorities – including demanding for justice. However, when the police is crippled and seemingly unable to ensure the prosecution of rights violations and extrajudicial killings, and they resort to twitter threads and hashtags to call out for justice, overhauling the security architecture is extremely necessary.

Documenting inequality: how much evidence is needed to change things?

In our society, there is a focus on documenting inequality and injustice. In the discipline of criminology (as with other social sciences) we question and read and take notes and count and read and take more notes. We then come to an evidence based conclusion; yes, there is definite evidence of disproportionality and inequality within our society. Excellent, we have identified and quantified a social problem. We can talk and write, inside and outside of that social problem, exploring it from all possible angles. We can approach social problems from different viewpoints, different perspectives using a diverse range of theoretical standpoints and research methodologies. But what happens next? I would argue that in many cases, absolutely nothing! Or at least, nothing that changes these ingrained social problems and inequalities.

Even the most cursory examination reveals discrimination, inequality, injustice (often on the grounds of gender, race, disability, sexuality, belief, age, health…the list goes on), often articulated, the subject of heated debate and argument within all strata of society, but remaining resolutely insoluble. It is as if discrimination, inequality and injustice were part and parcel of living in the twenty-first century in a supposedly wealthy nation. If you don’t agree with my claims, look at some specific examples; poverty, gender inequality in the workplace, disproportionality in police stop and search and the rise of hate crime.

- Three years before the end of World War 2, Beveridge claimed that through a minor redistribution of wealth (through welfare schemes including child support) poverty ‘could have been abolished in Britain‘ prior to the war (Beveridge, 1942: 8, n. 14)

- Yet here we are in 2019 talking about children growing up in poverty with claims indicating ‘4.1 million children living in poverty in the UK’. In addition, 1.6 million parcels have been distributed by food banks to individuals and families facing hunger

- There is legal impetus for companies and organisations to publish data relating to their employees. From these reports, it appears that 8 out of 10 of these organisations pay women less than men. In addition, claims that 37% of female managers find their workplace to be sexist are noted

- Disproportionality in stop and search has long been identified and quantified, particularly in relation to young black males. As David Lammy’s (2017) Review made clear this is a problem that is not going away, instead there is plenty of evidence to indicate that this inequality is expanding rather than contracting

- Post-referendum, concerns were raised in many areas about an increase in hate crime. Most attention has focused on issues of race and religion but there are other targets of violence and intolerance

These are just some examples of inequality and injustice. Despite the ever-increasing data, where is the evidence to show that society is learning, is responding to these issues with more than just platitudes? Even when, as a society, we are faced with the horror of Grenfell Tower, exposing all manner of social inequalities and injustices no longer hidden but in plain sight, there is no meaningful response. Instead, there are arguments about who is to blame, who should pay, with the lives of those individuals and families (both living and dead) tossed around as if they were insignificant, in all of these discussions.

As the writer Pearl S. Buck made explicit

‘our society must make it right and possible for old people not to fear the young or be deserted by them, for the test of a civilization is in the way that it cares for its helpless members’ (1954: 337).

If society seriously wants to make a difference the evidence is all around us…stop counting and start doing. Start knocking down the barriers faced by so many and remove inequality and injustice from the world. Only then can we have a society which we all truly want to belong to.

Selected bibliography

Beveridge, William, (1942), Report of the Inter-Departmental Committee on Social Insurance and Allied Services, (HMSO: London)

Buck, Pearl S. (1954), My Several Worlds: A Personal Record, (London: Methuen)

Lammy, David, (2017), The Lammy Review: An Independent Review into the Treatment of, and Outcomes for, Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic Individuals in the Criminal Justice System, (London: Ministry of Justice)

Have you been radicalised? I have

On Tuesday 12 December 2018, I was asked in court if I had been radicalised. From the witness box I proudly answered in the affirmative. This was not the first time I had made such a public admission, but admittedly the first time in a courtroom. Sounds dramatic, but the setting was the Sessions House in Northampton and the context was a Crime and Punishment lecture. Nevertheless, such is the media and political furore around the terms radicalisation and radicalism, that to make such a statement, seems an inherently radical gesture.

So why when radicalism has such a bad press, would anyone admit to being radicalised? The answer lies in your interpretation, whether positive or negative, of what radicalisation means. The Oxford Dictionary (2018) defines radicalisation as ‘[t]he action or process of causing someone to adopt radical positions on political or social issues’. For me, such a definition is inherently positive, how else can we begin to tackle longstanding social issues, than with new and radical ways of thinking? What better place to enable radicalisation than the University? An environment where ideas can be discussed freely and openly, where there is no requirement to have “an elephant in the room”, where everything and anything can be brought to the table.

My understanding of radicalisation encompasses individuals as diverse as Edith Abbott, Margaret Atwood, Howard S. Becker, Fenner Brockway, Nils Christie, Angela Davis, Simone de Beauvoir, Paul Gilroy, Mona Hatoum, Stephen Hobhouse, Martin Luther King Jr, John Lennon, Primo Levi, Hermann Mannheim, George Orwell, Sylvia Pankhurst, Rosa Parks, Pablo Picasso, Bertrand Russell, Rebecca Solnit, Thomas Szasz, Oscar Wilde, Virginia Woolf, Benjamin Zephaniah, to name but a few. These individuals have touched my imagination because they have all challenged the status quo either through their writing, their art or their activism, thus paving the way for new ways of thinking, new ways of doing. But as I’ve argued before, in relation to civil rights leaders, these individuals are important, not because of who they are but the ideas they promulgated, the actions they took to bring to the world’s attention, injustice and inequality. Each in their own unique way has drawn attention to situations, places and people, which the vast majority have taken for granted as “normal”. But sharing their thoughts, we are all offered an opportunity to take advantage of their radical message and take it forward into our own everyday lived experience.

Without radical thought there can be no change. We just carry on, business as usual, wringing our hands whilst staring desperate social problems in the face. That’s not to suggest that all radical thoughts and actions are inherently good, instead the same rigorous critique needs to be deployed, as with every other idea. However rather than viewing radicalisation as fundamentally threatening and dangerous, each of us needs to take the time to read, listen and think about new ideas. Furthermore, we need to talk about these radical ideas with others, opening them up to scrutiny and enabling even more ideas to develop. If we want the world to change and become a fairer, more equal environment for all, we have to do things differently. If we cannot face thinking differently, we will always struggle to change the world.

For me, the philosopher Bertrand Russell sums it up best

Thought is subversive and revolutionary, destructive and terrible; thought is merciless to privilege, established institutions, and comfortable habits; thought is anarchic and lawless, indifferent to authority, careless of the well-tried wisdom of the ages. Thought looks into the pit of hell and is not afraid. It sees man, a feeble speck, surrounded by unfathomable depths of silence; yet it bears itself proudly, as unmoved as if it were lord of the universe. Thought is great and swift and free, the light of the world, and the chief glory of man (Russell, 1916, 2010: 106).

Reference List:

Russell, Bertrand, (1916a/2010), Why Men Fight, (Abingdon: Routledge)

Forgotten

It is now nearly two weeks since Remembrance Day and reading Paula’s blog. Whilst understanding and agreeing with much of the sentiment of the blog, I must confess I have been somewhat torn between the critical viewpoint presented and the narrative that we owe the very freedoms we enjoy to those that served in the second world war. When I say served, I don’t necessarily mean those just in the armed services, but all the people involved in the war effort. The reason for the war doesn’t need to be rehearsed here nor do the atrocities committed but it doesn’t hurt to reflect on the sacrifices made by those involved.

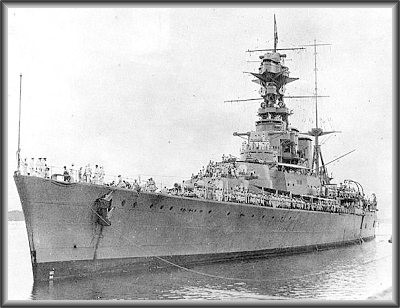

My grandad, now deceased, joined the Royal Navy as a 16-year-old in the early 1930s. It was a job and an opportunity to see the world, war was not something he thought about, little was he to know that a few years after that he would be at the forefront of the conflict. He rarely talked about the war, there were few if any good memories, only memories of carnage, fear, death and loss. He was posted as missing in action and found some 6 months later in hospital in Ireland, he’d been found floating around in the Irish Sea. I never did find out how this came about. He had feelings of guilt resultant of watching a ship he was supposed to have been on, go down with all hands, many of them his friends. Fate decreed that he was late for duty and had to embark on the next ship leaving port. He described the bitter cold of the Artic runs and the Kamikaze nightmare where planes suddenly dived indiscriminately onto ships, with devastating effect. He had half of his stomach removed because of injury which had a major impact on his health throughout the rest of his life. He once described to me how the whole thing was dehumanised, he was injured so of no use, until he was fit again. He was just a number, to be posted on one ship or another. He swerved on numerous ships throughout the war. He had medals, and even one for bravery, where he battled in a blazing engine room to pull out his shipmates. When he died I found the medals in the garden shed, no pride of place in the house, nothing glorious or romantic about war. And yet as he would say, he was one of the lucky ones.

My grandad and many like him are responsible for my resolution that I will always use my vote. I do this in the knowledge that the freedom to be able to continue to vote in any way I like was hard won. I’m not sure that my grandad really thought that he was fighting for any freedom, he was just part of the war effort to defeat the Nazis. But it is the idea that people made sacrifices in the war so that we could enjoy the freedoms that we have that is a somewhat romantic notion that I have held onto. Alongside this is the idea that the war effort and the sacrifices made set Britain aside, declaring that we would stand up for democracy, freedom and human rights.

But as I juxtapose these romantic notions against reality, I begin to wonder what the purpose of the conflict was. Instead of standing up for freedom and human rights, our ‘Great Britain’ is prepared to get into bed with and do business with the worst despots in the world. Happy to do business with China, even though they incarcerate up to a million people such as the Uygurs and other Muslims in so called ‘re-education camps’, bend over backwards to climb into bed with the United States of America even though the president is happy to espouse the shooting of unarmed migrating civilians and conveniently play down or ignore Saudi Arabia’s desolation of the Yemini people and murder of political opponents.

In the clamber to reinforce and maintain nationalistic interests and gain political advantage our government and many like it in the west have forgotten why the war time sacrifices were made. Remembrance should not just be about those that died or sacrificed so much, it should be a time to reflect on why.

‘The Problem We All Live With’

The title of this blog and the picture above relate to Norman Rockwell’s (1964) painting depicting Ruby Bridges on her way to school in a newly desegregated New Orleans. In over half a century, this picture has never lost its power and remains iconic.

Attending conferences, especially such a large one as the ASC, is always food for thought. The range of subjects covered, some very small and niche, others far more longstanding and seemingly intractable, cause the little grey cells to go into overdrive. So much to talk about, so much to listen to, so many questions, so many ideas make the experience incredibly intense. However, education is neither exclusive to the conference meeting rooms nor the coffee shops in which academics gather, but is all around. Naturally, in Atlanta, as I alluded to in my previous entry this week, reminders of the civil rights movement are all around us. Furthermore, it is clear from the boarded-up shops, large numbers of confused and disturbed people wandering the streets, others sleeping rough, that many of the issues highlighted by the civil rights movement remain. Slavery and overt segregation under the Jim Crow laws may be a thing of the past, but their impact endures; the demarcation between rich and poor, Black and white is still obvious.

The message of civil rights activists is not focused on beatification; they are human beings with all their failings, but far more important and direct. To make society fairer, more just, more humane for all, we must keep moving forward, we must keep protesting and we must keep drawing attention to inequality. Although it is tempting to revere brave individuals such as Ruby Bridges, Claudette Colvin, Martin Luther King Jr, Rosa Parks, Malcolm X to name but a few, this is not an outcome any of them ascribed to. If we look at Martin Luther King Jr’s ‘“The Drum Major Instinct” Sermon Delivered at Ebenezer Baptist Church’ he makes this overt. He urges his followers not to dwell on his Nobel Peace Prize, or any of his other multitudinous awards but to remember that ‘he tried’ to end war, bring comfort to prisoners and end poverty. In his closing words, he stresses that

If I can help somebody as I pass along,

If I can cheer somebody with a word or song,

If I can show somebody he’s traveling wrong,

Then my living will not be in vain.

If I can do my duty as a Christian ought,

If I can bring salvation to a world once wrought,

If I can spread the message as the master taught,

Then my living will not be in vain.

These powerful words stress practical activism, not passive veneration. Although a staunch advocate for non-violent resistance, this was never intended as passive. The fight to improve society for all, is not over and done, but a continual fight for freedom. This point is made explicit by another civil rights activist (and academic) Professor Angela Davis in her text Freedom is a Constant Struggle. In this text she draws parallels across the USA, Palestine and other countries, both historical and contemporaneous, demonstrating that without protest, civil and human rights can be crushed.

Whilst ostensibly Black men, women and children can attend schools, travel on public transport, eat at restaurants and participate in all aspects of society, this does not mean that freedom for all has been achieved. The fight for civil rights as demonstrated by #blacklivesmatter and #metoo, campaigns to end LGBT, religious and disability discrimination, racism, sexism and to improve the lives of refugees, illustrate just some of the many dedicated to following in a long tradition of fighting for social justice, social equality and freedom.

Congratulations, but no Celebrations

A few weeks ago, Sir Cliff Richard won his high court case against the BBC over the coverage of a police raid on his home, the raid relating to an investigation into historical sex abuse. I remember watching the coverage on the BBC and thinking at the time that somehow it wasn’t right. It wasn’t necessarily that his house had been raided that pricked my conscience but the fact that the raid was being filmed for a live audience and sensationalised as the cameras in the overhead helicopter zoomed into various rooms. A few days later in the sauna at my gym I overheard a conversation that went along the lines of ‘I’m not surprised, I always thought he was odd; paedo just like Rolf Harris’. And so, the damage is done, let’s not let the facts get in the way of a good gossip and I dare say a narrative that was repeated up and down the country. But Sir Cliff was never charged nor even arrested, he is innocent.

The case reminded me of something similar in 2003 where another celebrity Matthew Kelly was accused of child sex abuse. He was arrested but never charged, his career effectively took a nose dive and never recovered. He too is innocent and yet is listed amongst many others on a website called the Creep Sheet. The name synonymous with being guilty of something unsavoury and sinister, despite a lack of evidence. The way some of the papers reported that no charges were to be brought, suggested he had ‘got away with it’.

The BBC unsuccessfully sought leave to appeal in the case of Sir Cliff Richard and is considering whether to take the matter to the appeal court. Their concern is the freedom of the press and the rights of the public, citing public interest. Commentary regarding the case suggested that the court judgement impacted victims coming forward in historical abuse cases. Allegations therefore need to be publicised to encourage victims to come forward. This of course helps the prosecution case as evidence of similar fact can be used or in the view of some, abused (Webster R 2002). But what of the accused, are they to be thrown to the wolves?

Balancing individual freedoms and the rights of others including the press is an almost impossible task. The focus within the criminal justice system has shifted and some would say not far enough in favour of victims. What has been forgotten though, is the accused is innocent until proven guilty and despite whatever despicable crimes they are accused of, this is a maxim that criminal justice has stood by for centuries. Whilst the maxim appears to be generally true in court processes, it does not appear to be so outside of court. Instead there has been a dramatic shift from the general acceptance of the maxim ‘innocent until proven guilty’ to a dangerous precedent, which suggests through the press, ‘there’s no smoke without fire’. It is easy to make allegations, not easy to prove them and even more difficult to disprove them. And so, a new maxim, ‘guilty by accusation’. The press cannot complain about their freedoms being curtailed, when they stomp all over everyone else’s.

Criminology: in the business of creating misery?

I’ve been thinking about Criminology a great deal this summer! Nothing new you might say, given that my career revolves around the discipline. However, my thoughts and reading have focused on the term ‘criminology’ rather than individual studies around crime, criminals, criminal justice and victims. The history of the word itself, is complex, with attempts to identify etymology and attribute ownership, contested (cf. Wilson, 2015). This challenge, however, pales into insignificance, once you wander into the debates about what Criminology is and, by default, what criminology isn’t (cf. Cohen, 1988, Bosworth and Hoyle, 2011, Carlen, 2011, Daly, 2011).

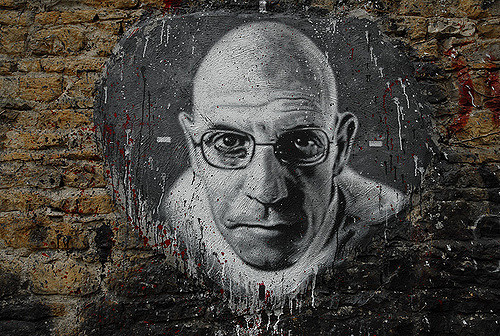

Foucault (1977) infamously described criminology as the embodiment of utilitarianism, suggesting that the discipline both enabled and perpetuated discipline and punishment. That, rather than critical and empathetic, criminology was only ever concerned with finding increasingly sophisticated ways of recording transgression and creating more efficient mechanisms for punishment and control. For a long time, I have resisted and tried to dismiss this description, from my understanding of criminology, perpetually searching for alternative and disruptive narratives, showing that the discipline can be far greater in its search for knowledge, than Foucault (1977) claimed.

However, it is becoming increasingly evident that Foucault (1977) was right; which begs the question how do we move away from this fixation with discipline and punishment? As a consequence, we could then focus on what criminology could be? From my perspective, criminology should be outspoken around what appears to be a culture of misery and suspicion. Instead of focusing on improving fraud detection for peddlers of misery (see the recent collapse of Wonga), or creating ever increasing bureaucracy to enable border control to jostle British citizens from the UK (see the recent Windrush scandal), or ways in which to excuse barbaric and violent processes against passive resistance (see case of Assistant Professor Duff), criminology should demand and inspire something far more profound. A discipline with social justice, civil liberties and human rights at its heart, would see these injustices for what they are, the creation of misery. It would identify, the increasing disproportionality of wealth in the UK and elsewhere and would see food banks, period poverty and homelessness as clearly criminal in intent and symptomatic of an unjust society.

Unless we can move past these law and order narratives and seek a criminology that is focused on making the world a better place, Foucault’s (1977) criticism must stand.

References

Bosworth, May and Hoyle, Carolyn, (2010), ‘What is Criminology? An Introduction’ in Mary Bosworth and Carolyn Hoyle, (2011), (eds), What is Criminology?, (Oxford: Oxford University Press): 1-12

Carlen, Pat, (2011), ‘Against Evangelism in Academic Criminology: For Criminology as a Scientific Art’ in Mary Bosworth and Carolyn Hoyle, (eds), What is Criminology?, (Oxford: Oxford University Press): 95-110

Cohen, Stanley, (1988), Against Criminology, (Oxford: Transaction Books)

Daly, Kathleen, (2011), ‘Shake It Up Baby: Practising Rock ‘n’ Roll Criminology’ in Mary Bosworth and Carolyn Hoyle, (eds), What is Criminology?, (Oxford: Oxford University Press): 111-24

Foucault, Michel, (1977), Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, tr. from the French by Alan Sheridan, (London: Penguin Books)

Wilson, Jeffrey R., (2015), ‘The Word Criminology: A Philology and a Definition,’ Criminology, Criminal Justice Law, & Society, 16, 3: 61-82