Home » Articles posted by Tré Ventour-Griffiths (Page 6)

Author Archives: Tré Ventour-Griffiths

From Poplar to Grenfell, and the lands between

In a previous blog post, I commented how the Period Drama is my favourite genre to watch. This year, it was interesting to see two of my favourite series talk about tower blocks. As we reach the third anniversary of Grenfell , I saw both Call the Midwife and Endeavour comment on how these tower blocks were optimistic schemes. As the tower blocks multiply in the London East End, a new society rises. Meanwhile, in Endeavour a tower block collapses in Oxfordshire (quite like Ronan Point in Canning Town: London, 1968). Watching both these shows, we know how this story ends, in ashes; poor people, immigrants, refugees, Black and brown people, people with disabilities as victims of the Grenfell Tower fire.

It is also tragic to see that in the stories of tower blocks in both series, there is also a Black history that goes beyond the show. In Call the Midwife’s ninth season, we encounter a patient with Sickle Cell, common in those of African descent. “The population around here is changing, I have to be prepared to deal with new things” says Dr. Turner. The arrival of the Windrush Generation, tied with the baby boom brought challenges for the state. Where would they house people? People in a society where Enoch Powell feared “the Black man would hold the whip hand over the White man.”

In Endeavour, the Cranmer House collapses, which may be inspired by the true-to-life incident of Ronan Point, a tower block in the Canning Town district in the East End of London. Ronan Point partially collapses a year and half before the events of ‘Degüello’ in the sixth season of Endeavour. In London, there were four fatalities and an additional seventeen were injured. Initially said to be a gas explosion, like at Cranmer, it was later deduced that Ronan Point’s collapse was due to structural deficiencies. Laws were eventually changed in hope of preventing incidents like this.

Though, that did not help those that died at Grenfell, where seventy-two (that were accounted for) lost their lives on June 14, 2017, including still-born Logan Gomes after his parents escaped the tragedy in the south-west of London.

However, this episode of Endeavour must be one of my favourites of any show I have seen. Not only for its sociohistorical significance, but for its ability to tell a story with excellent pacing in a way that I only really see in journalism films, such as The Post (starring Meryl Streep and Tom Hanks) Not at any moment is this boring to watch (nor is the entirety of the series). Each episode of Endeavour plays out almost like a film noir. Especially ‘Degüello’, which makes me think of Roman Polanski’s Chinatown (1974).

When a librarian is murdered at Oxford’s world famous Bodleian, DS Endeavour Morse and DI Thursday have no leads but a pair of muddy boot prints. With both suspects having motives, Morse explores into their pasts, showing bribery and corruption at the highest level, including links to Cranmer and the murder of their colleague DC George Fancy. In its ninety minutes, ‘Degüello’ is pure edge-of-your-seat drama. It must be one of my favourite season finales of all-time. And that is high praise, indeed.

Early on we already begin to see the cracks in Cranmer. Quite literally. When tragedy strikes, it is up to Morse and company to find the survivors in the rubble of what was supposed to be an optimistic look at Britain of the future. Watching shows set in the 1960s, it’s eerie to know how this story ends (if it has ended at all). In this time of Coronavirus we are in a country with a 30,000+ death toll, many of which could have been prevented. The same can be said with Grenfell, where stakeholders seemingly cut corners to save money and at least seventy-two people unnecessarily lost their lives.

With these two shows set in the same time period, both with commentaries on tower blocks (CTM’s being a looser narrative), we in the present have the gift of hindsight. Yet, with Grenfell we continue to make the same mistakes. If they are mistakes at all. Did the state’s contempt for the working class begin with Grenfell? No, just look at Charles Dickens novels, or how the characters of Wuthering Heights treat Heathcliff who Mr Earnshaw brought back from Liverpool. These are works of fiction, but how fictional are they? Art imitates life, but when life starts imitating art is what scares me.

For centuries, those that have, have always treated those that don’t with disdain. Whether that’s the actions of the British Empire; or the use of child labour (see the Factory Act, didn’t do much). Or the Mines Act (1842) prohibiting girls and women working the mines. Nonetheless, today’s progress on equalities, including the Human Rights Act (1998) would also dictate that the Factory Act (1833) as not fit for purpose, with age ten as the minimum age for boys to work the mines. English common sense indeed!

How fictional are the stories of Dickens, the Bronte Sisters, or Thackeray’s Vanity Fair that comment on class? With the ongoing investigation into the Grenfell Tower tragedy, how will the history books look back on it, in say a century? What about the Windrush Scandal? In the ‘Case of Jarndyce and Jarndyce’, in Bleak House, it ends with nobody getting anything. Years of legal fees and legal jargon that nobody understands. Both Call the Midwife and Endeavour show characters at the mercy of systems. A London tower block black as coal doesn’t discriminate but institutions do, systems do.

When you run Grenfell, Ronan, Cranmer, or even the Coronavirus pandemic parallel to British history, is it really surprising that the state is cutting corners, readily throwing society’s most vulnerable, including the poor, under the bus?

Is film dying, or am I overthinking this, again?

I think we’re at a point now that television is at its creative peak, while film is in a slump. Television in 2020 is where film was at in the 1970s. Though, I also question if my recent critique of the industry is, if I’m simply a victim of golden age thinking. That in believing that industry is lawless because the gatekeepers care more about money than creativity, where once there was a healthy mix of both. Are today’s mainstream films made for me? Am I the audience for it? In the tint of toxic fan bases (big up Star Wars) Or if simply, most films made today are just bad? When I go to the cinema, am I thinking too hard or do I have unrealistic expectations? Is wanting a good story making bank too much?

I wouldn’t say they’re necessarily bad, just samey. I think the recent Star Wars trilogy is great. It’s flashy. It’s fun. But ultimately, it’s samey. I do understand where my parents’ generation are coming from when they say that they didn’t like the last Star Wars trilogy. I think there are lots of good even excellent films made today, I simply think we the public are too forgiving of mediocrity, whilst praising bad films that are good for business. In lockdown, I’m finding even more so why I prefer films made before 2000, and finding it hard not to say that films made today, generally are in a tough spot compared to when my parents and grandparents were growing up.

As I mentioned above, television is where film was in the 1970s. Now, before I cause any upset, I’m not generalising, because my favourite film of all time came out in 2011, Midnight in Paris. There are plenty of excellent pictures that have come out in the twenty-first century. From Lord of the Rings to Moonlight. 2017 was a great year, also giving us Dunkirk, Get Out, Logan, The Post, Wind River and Mudbound. Moreover, Detroit and Death of Stalin. I am always impressed with Christopher Nolan and Aaron Sorkin.

And regardless of how much I hear people complain at the lack of originality in the businness today, due to remakes, reboots and so forth, none of that compares to Ghostbuster 2. Nonetheless, that doesn’t detract from how in our complacency as a society we have grown to accept mediocrity over the importance of The Story that dominated film before the turn of the century. I think it was Hitchcock who said “to make a great film, you only need three things – the script, the script, the script.”

In a conversation with another film enthusiast, we were talking about how many filmmakers we like who are also problematic characters. Woody Allen, being one I have a love-hate relationship with. I think he’s one of the funniest writers alive but his controversy makes me uncomfortable to say the least. Clarke Gable, a fabulous actor of Old Hollywood, but he would not have survived #metoo in today’s world. In light of Weinstein, it got me to think about my own biases when watching film and assessing goodness.

Some people find it difficult to seperate art from the artist, and that inability to split the two can inform bias on a piece of art’s badness. That somebody will dislike any Kevin Spacey film because of what came to light in #metoo. Yet, I still believe he is one of the greatest actors of his generation. How he brings Frank Underwood to life in House of Cards brings tears to my eyes. But from the 1930s through to the back end of the 1980s, it’s racism and sexism galore. i.e like every James Bond film ever!

“I was lucky to get into film at a time that was very interesting for drama. But if you look now, the focus is not on the same kind of films that were made in the 90s. When I look now, the most interesting plots, the most interesting characters, they are on TV.”

Kevin Spacey

Are the things that make bank today made for me? Is there a cultural shift now similar to how the mob genre practically died at the turn of the century? Hollywood does have “Marvel Fever” and I do enjoy them. Yet, there was a point when the industry would green light any western, where John Wayne would be chasing indigenous peoples on horseback. Studios would green-light gangsters and film noir. Hollywood likes what’s good for business. I believe the only difference between now and then, is that people are more complacent, and there’s more of a spoon-feeding culture today.

Before the internet, my parents talk of a time when you had to use your critical faculties where information wasn’t given to you instantaneously. Now, we just expect everything immediately, including stories. The problem is not with what’s being made, it’s with how it’s being made. Quality, not genre. There is a reason why the original Star Wars Trilogy has universal appeal across multiple generations. There is a reason why Steven Spielberg has had an iconic film for every decade of his career with universal appeal.

The problem with many films today is the shift from good storytelling into genre storytelling, replacing good writing with special effects and fan service. I’m a fan of this “superhero fever” but that doesn’t mean I will shy away from critique, and they are very problematic, along with many action blockbusters. The reason why I prefer what Fox did with X-Men, as flawed as it was, is that it focussed on story(ish) and not mythology. With Marvel, it’s always “the next film” but Fox kept me on the present pane of existence.

I loved 2017 because there were many films that kept me grounded. Moonlight, Get Out, La La Land, The Big Sick, Molly’s Game; it was how I get from point A to point B. What about this character? Why should I care about them? 2017 had many films where there were lots of characters that made me feel things, similar to the number of films that came out before 2000. That when I watch Goodfellas, my heart breaks when Tommy (Joe Pesci) gets whacked. Today, I couldn’t care less if this and this person dies.

I am not sure whether that is because I am not the audience, I’m an anomaly or if I am a heartless bastard, or a mixture

Lots of drama films just seem flat. Or am I just not the audience? What ever happend to films like Doubt, where [Queen] Viola Davis gives one of the best performances ever? When I watch works like Netflix series Stranger Things, I remember I have seen it before. I remember my father showing it to me as a kid. It came out in 1985. Sean Astin, Josh Brolin. It’s called Goonies. Though, I loved Get Out, the golden egg in the sea of turds that was the 2018 Best Picture race. Interesting story. Explored its characters. Emotional resonance. Jordan Peele, then followed that with Us. Fab.

Yet, I’ve seen some great ones recently, including: The Post, Spotlight and The Big Short. They are great in the moment but forgettable, as much as I hate to admit it. Where have all the writers gone? Honestly, they’re killing it on television. God bless Star Wars: The Clone Wars. Television is film in the 1970s: Killing Eve, Clone Wars, Girls, House of Cards, Westworld. When something as excellent as Scorsese’s Silence tanked in the box office, this is when you know there’s a culture shift, and it broke my heart to see that.

Take Last Kingdom (on the Netflix platform), a medieval historical drama series that has the storytelling Outlaw King / The King wish they did. Excellent characters, brooding, and emotional resonance (as any drama should be)

Whilst stories like Last Kingdom would once be made as films (Braveheart), they’re now being made as television series. Whilst lack of original ideas, focus on remakes, sequels etc etc could be used as a reason to justify the decline of film, a more plausible reason could be that television was never really a credible competition for film until recently (last 10 – 15 years). In addition to marketing, particularly trailers (and samey posters). Pre-2000, you’d have once had some interesting posters. Now, most look done to template. Ultimately, boring. Yet, this seems to be good for business.

Trailers do not represent the film, and often miss the feel of the film. One of my favourite films ever made is Goodbye Christopher Robin on the relationship between children’s author A. A. Milne and his son Christopher Robin (or Billy). A drama film whose trailers sells it as a light-hearted early to mid 20th century period drama about families. But when you watch the film, it’s about post traumatic disorder and one man’s quest in overcoming the angst of war. Thus we have the children’s classic Winnie the Pooh.

It presents Alan Milne as a product of a generation of men who were socialised into thinking that “affection” is a bad thing. Toxic masculinnity tied with the trauma of war made for a troubled relationship between him and his son. Its trailers make it seem like a harmless period costume drama but it explores the trauma of war and the emotional distance, of people who were products of that Victorian “common sense” nonsense at the turn of the 20th century. I implore all to watch it but its trailers certain missell it.

Going back to how I started this blog entry, I really do enjoy many films that are released today. However, I know many of them to be nothing but autopilot drivel that are specacle more than anything else. I know I would sooner watch a good television show but I still enjoy the novelty of going to the cinema and seeing something on a massive screen. Even if I know I won’t necessarily like what’s on show. I do wish some of these TV writers would come back to cinema because the quality is fading and it shows.

And I do often wonder if in the near future we will get to a point where companies like the BBC, HBO, Netflix or Amazon Prime will start to show episodes of television at cinemas in the same way we pay go to watch films

Love Film: You Can’t Blame The Youth

On the basis of a reliable academic study, research by The University’s top senior lecturers on Criminology, I am by their words and definition “the Youth of Today.” However, my younger brother (age 12) is The Youth of Tomorrow. In our group chat, this ongoing conversation (now months old) also includes (not Harvard) references to The Youth of Yesterday (age 30+) or Yesteryear (if you’re ancient, ahem). It’s really quite amusing. Am I The Youth of Today? I hadn’t listened to any Stormzy until he did Glastonbury and our conversations around “Vossi Bop” really are worthy of critical acclaim. Is one’s youth status pigeon-holed to their date of birth?

By the time I was 17, I had watched most of Hitchcock’s catalogue and I think Woody Allen is one of the funniest writers alive (despite his controversy). Is this the point in the blog where I need to mention someone other than a White man? Again, another point of discussion in our chats. Diversity. So, true to form, I have seen the entire filmography of Vivien Leigh. I think Diane Keaton is understated in The Godfather films and Claudine with Diahann Carroll is underrated, and should be on seminal film lists when we talk about working-class life in America. It’s a lesson to us now in Britain, haunted by depressions of austerity and universal credit.

Yet, this blog isn’t about group chats, but generalisations. Are today’s youth beyond the grasp of Old Hollywood or even films made before the 2000s that aren’t franchise, or nostalgia pictures like Jumanji? I aim this question at The Youth of Tomorrow too (born post-7/7). Is it true? Maybe, maybe not. The idea remains that many people despite age are still dismissive of Old Hollywood in general, and the classic films made before the 1990s.

Criminology senior lecturer @paulaabowles has an affinity for Agatha Christie but seldom do I hear young people talk about Agatha when thinking crime stories, be it literature or not. I hear much love for Idris Elba as DI John Luther. Yet, it is arguable to say there would be no modern whodunnit without the massive contributions of crime writer Agatha Christie, who a century ago was defining the things we now we would call clichés. These people are seriously missing out by dismissing “The Old”. All it takes is the right story to alter perceptions, changing minds forever.

I do love to read, but film / the moving-image is more my thing. One of my favourite films is Mr Smith Goes to Washington. I’m of that generation that some of the boomer generation are talking about when they say “kids today” in relation to not enjoying the films that were around in their youth. I watched this film when I was 19 and I still am surprised by how complex yet simple it is. Audiences who have watched things like Veep, Netflix’s House of Cards or Thick of It will get on with James Stewart as Mr Smith.

Its searing portrayal of how systems of power crush good people just wanting to do the right thing can still be seen in society today; from politics to policing, exploring corruption and greed in the deeply flawed human imagination whilst simultaneously acting as a commentary for humanity’s blitz spirit in a film, which I would not be surprised influenced Stan Lee in creating the character of Captain America in 1941. No matter how hard you try, what keeps human beings going is their determination to fight on.

I could be offended at people that say my generation “wouldn’t know a good film if it was staring at them in the face” because “Hollywood only now makes films for sixteen year-olds and China” (both real quotes) but I’m not, because in my experience outside of online film groups on Facebook, and Film Twitter, I have seen this to be true. I will never forget the time when a former-colleague refused to watch Ridley Scott’s Alien because it was old.

When people ask me for recommendations, I need to get a notion of that person’s likes first in case I get a repeat Alien situation (I am still salty about this) Nonetheless, I think everyone should watch classic cinema, including black and white films, as they are some of the best films ever made.

In a time now where sex sells, another in for classic cinema would be to introduce them to Old Hollywood through pictures like Some Like It Hot. Most people have heard of Marilyn Monroe, and the Youth of Today or Yesterday may in fact be seduced by the “crude” title and its star, only then to get mesmerised by a God-ordained masterpiece of American cinema, mixing film noir with banter and action, a film that is certainly not boring.

Though, very much a product of the late 1960s, To Sir with Love hasn’t aged a day. Growing up in a household where education and learning were core values, watching this film at 20 was a homecoming for me. Only to then screen it at the Students’ Union as part of Black History Month 2019. It reminds me of today in how we are in a sector where many students don’t want to learn and many teachers don’t want to teach, before we even get to issues of disparities of outcomes between different student groups.

Mark Thackeray (Sidney Poitier) is the teacher we all wish we had, and certainly an entrance into Old Hollywood for The Youth of Tomorrow, let alone the wonderful song by Lu Lu. To Sir, with Love is optimistic while still commenting on social issues, including race and class. It’s pure of heart in its ideas about British education but also access to education for poor working-class communities in the East End of London. Moreover, how teaching back then was a noble profession and a pillar of the community.

If “kids today” are to have access to these films, it will often be how I had access to them. Through a clunky VHS system at school watching things for English class like Elia Kazan’s A Streetcar Named Desire. I will never forget the time my brother asked me what a VHS was. And I then thought I had failed my duties. Or am I just passed it? Does he think I’m ancient? I think we’re at DVD now, or even BluRay? Who decides what a classic is? That’s another question and that debate will have to wait for another time.

Do kids today know who Steven Spielberg is? He has had a defining film for every decade of his career. Surely, they know who he is? They must have watched Jaws? Sometimes, I want to despair but I was in their position once, possibly when I was in nappies. I think I might have had grey hair then too. As we all sit in lockdown, there is no better time to watch the epics. Whilst many of us will be bingeing the likes of Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings, what about the epics of the silver screens of Old Hollywood?

When talking to young people, we do often look at how accessible a film is, and whether it’s in high definition? Those are two selling points. Gone with the Wind, Giant, Lawrence of Arabia, Cleopatra, Doctor Zhivago, Spartacus, Ben-Hur – these are some of my favourite epics. Cleopatra sits at a wholesome 5hrs 20mins. These were event films in the same way we court Lord of the Rings today. We don’t get many event films anymore but you can’t blame the youth for not knowing what they do not know.

And with a massive diversity of content across streaming platforms like Netflix and Amazon Prime as well, do the Youth of Today (and Tomorrow) need older films, or am I locked in the time trap of nostalgia and golden age thinking?

Is my obsession with cinema just golden age thinking?

The past four weeks we’ve been in isolation is the longest period I’ve gone without going to the cinema in four years. As a holder of a Cineworld card, the cinema comes as natural to me as breathing. However, seemingly, with the arrival of streaming platforms, including Netflix and Amazon Prime, as well as access to films through torrenting, fewer people are going to the cinema when we can watch films at home with the added bonus of pausing it when you want to go to the toilet. And going to the cinema with your family is a pastime that millions of people across the world take part in. For many families, going to see the latest blockbuster is fun, but for me it’s more a home from home.

Flicking between streaming platforms, my books and other forms of entertainment, it’s given me time to contemplate about things I’m interested in, including the film industry

Since childhood, I’ve always had a respect for storytelling through the moving image, being force-fed Disney at five years old. And is it possible to enjoy 20th-century Disney films whilst seeing all the racist, sexist, misogynistic messages and imagery they hold? Nonetheless, from memory, one trip to the cinema with my parents was in the summer of 2005 at the release of Star Wars: Revenge the Sith. Then, I loved it. Now, I loathe it. Yet, in 2005, I recall going to the cinema was a family affair. An event.

Nowadays, your Joe and Jane Bloggs seem to go to the cinema because of an 85% fresh rating on Rotten Tomatoes.

What put it into perspective was when Martin Scorsese’s Silence (2016) tanked in the box office. Alas, subjectively one of the best films of 2016 and Scorsese knows his craft – from Mean Streets (1973), to Goodfellas (1990), to today with The Irishman (2019). You’re only as good as your last, and I don’t think he has ever done a bad film. Film now is less about filmmaking or going to the cinema as an event, and more about spectacle. Whilst board execs of big production companies still wanted to make money in the old days, it’s evident that Old Hollywood still had an equilibrium between maintaining standards of quality and making money in the box office.

I grew up around Double Indemnity, The Third Man, Cleopatra, Gone with the Wind and Giant, let alone Detective Virgil Tibbs, Norman Bates and Miss Blanch DuBois.

Heck, even films like Richard Roundtree in Shaft (1971), as politically incorrect as it is. And many of my family are of a delicate disposition! There are no “movie stars” anymore. Whilst once, people would have gone to watch that Harrison Ford film, as he was was the golden child of the 1980s (Blade Runner, Indiana Jones), now it’s about franchise. Robert Downey Jr. isn’t a movie star, Tony Stark is. Whilst my parents grew up going to see the latest Harrison Ford film, now it’s about the latest in the Fast and Furious franchise, or the next sequel, or Disney remake (as much I enjoy them).

The emergence of the Marvel Cinematic Universe changed the way Hollywood did business forever, especially since 2012 with Avengers Assemble which was unprecedented, let alone Infinity War and Endgame. The coming of these vigilantes has meant the death of filmmaking as we knew it. The [metaphorical] death of movie stars such as Stallone, Schwarzenegger and Will Smith. Whilst films were once made for, at least in-part, due to love of the art, now it’s about making bank in what feels like tinting the lense of nostalgia in the public consciousness. Goonies would never get made today, so let’s put it on Netflix and call it Stranger Things.

I hear the elderly, and even my parents’ generation use terms like “kids today” and the “youth of today.” And I really do feel bad for my brothers’ generation, who grew up with social media and will never know a film industry before the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Born in 2008, he is now twelve years old and was born in the same year Robert Downey Jr. debuted as Tony Stark in Iron Man (2008). When folks say kids today, I’m not sure whether they mean me (I’m 24) or him (12). When I say it, I mean children.

Born in 1995, I came into this world with Jumanji (1995), Home Alone (1990) and Matilda (1996). Moreover, the whole Disney catalogue was rammed down my throat dating back to Snow White (1939). Home Alone would not get made today. Jumanji would not get made today (not like that). My parents had Goonies (1985) and E.T the Extra-Terrestrial (1982), which would not get made today. I grew up with the same references my parents did, including Back to the Future (1985), meanwhile my brother / his peers watch YouTubers like it’s television (which I continue to find perplexing).

The way my parents talk about growing up in the 1980s, makes me envy them even more. I’m incredibly jealous of that generation. Whilst capitalism was still a thing, there was more love for storytelling. Going to the cinema now is about companies making bank, whilst then and even up to pre-2008 it was about making good films that made bank. And I think that’s why a lot of people are reluctant to go to the cinema and spend over £100 for a family of five. Most films that come out of the Hollywood system are bad. I take more pleasure out of independent films, art house, foreign films (big up Parasite) where they often still make films that are good for art’s sake.

I loved Jumanji: Welcome to the Jungle and Beauty and the Beast (2017) as well as, Jon Favreau’s Jungle Book (2016), but do we need to keep remaking films and giving them sequels? Some of my favourites, including Scarface (1983) and Ben-Hur (1959) are remakes, but they add to their predecessors, rather than bringing nothing new to what was already a perfectly reasonable film. The Godfather (1972), 12 Angry Men (1957), Psycho (1960) –lock them in an unbreakable vault and throw away the key! Coming to America (1988), 48 Hours (1982), Annie Hall (1977), you can’t copy that!!

I spend a lot of time at my favourite place, the cinema. It’s bliss. I watch the blockbusters but spend an awful lot of time watching the low-key films. Supporting the types of artists that will probably be struggling due to the social impact of Coronavirus. The fact that I had to travel to Birmingham to watch Moonlight on its release speaks volumes. Many of the films I want to watch get a limited release. The cinema is sacred. I’m not certain we can say it’s dying yet, but the psychology of going to the cinema has changed.

Being holed up because of the pandemic has further shown me why I so enjoy films made before the 1970s, when there were more films that were good made for art sake; however, when they were bad, you could not hide its badness behind stylish camera angles and ostentatious uses of special effects

Things I Miss, or Introverts vs Coronavirus

The thing I hate most about self-isolation is how quickly I eased into this new pace of life. Is that the privilege of having somewhere to self-isolate to or does it come with having an introverted personality? Before quarantine, many would perceive me as a mild-mannered individual. I ask a lot of questions. I guess that’s where my affinity for journalism comes from. Yet, in a global crisis, not much has changed. For someone that suffers from anxiety, one would think I would have more emotional unrest during the worst public health crisis in a generation. But no. I’m content, staying at home.

Whilst this pandemic has been liberating for me, it has shown how much privilege I still have despite being at three disadvantages in society: the colour of my skin, my invisible disability and being an introvert in a world designed for extroverts. Yet, cabin fever does set in once in a blue moon and sometimes it does feel like Groundhog Day. Despite being at comfort in my own space, my concept of time is being challenged. Like, what is a weekend? Not even Bill Murray can save me from this paradox. Not my books, nor Disney+ subscription, films, or The Doctor, Martha and that fogwatch.

What I hate about being an introvert in the buzz term of today – “unprecedented times” – is how I’m not suffering like my extroverted friends. Perhaps this is what it means to live in society designed to accommodate you. The world outside of a health crisis – is this what it’s like? Imagine if I also happened to be an able-bodied, White, straight man as well? Just imagine. Today, extroverts are suffering. Ambiverts are suffering. When this is over will we see an increase in agoraphobia?

And in a society where extroverts are privileged over introverts, the outgoing outspoken marketing professional is valued more than the introverted, reclusive schoolteacher.

Yet, today, we are seeing the value of nurses, doctors, teachers, lecturers / academics and so forth. Many of whom will be introverts going against the grain of what feels normal to them. The person seen to be outgoing and talking and networking is regarded as a team player, in comparison to the freelance blogger or journalist writing away on their computer at home. Many of my teacher friends that talk for a living also love to recluse in their homes, as drinking your own drinks and eating your own food in your own house is great. Can you hear the silence, the world in mute? Priceless.

In my job, I recall in the training we did the Myers-Briggs test in order to get to know each other better. Safe to say I was 97% introvert, which had increased somewhat since I was a student. Coincidence, I think not. In a job where I also go to meetings for a living, and network and people (if I can make a verb out of people), it can be draining. The meetings, the networking, the small talk, the different hats and masks people wear.

As awful as Coronavirus is, I will go back to my intro in saying that this new pace of life is almost like a dream, with intermittent periods of cabin fever. I can recharge my life batteries when I want. I can be alone when I want. I can read, watch films and television series when I want. I like to engage in activities that require critical thought. Self-isolation has given ample time for that. And good things have come from my introspection. Moreover, many conversations with myself. No, I’m not Bilbo Baggins. However, to talk with oneself is freeing. It’s the first sign of intelligence, don’t ya know?

But self-isolation to me and many of my introvert colleagues, it’s our normal. Social distancing is a farce because we are still being social. “Physical distancing” is a better term. Not in this era of WhatsApp, Instagram and Zoom, we’ve never been more social. Coronavirus has shown us a social solidarity that I thought I would not see in my lifetime. To put it bluntly, Coronavirus has pretty much eliminated the quite British obsession of small talk, and given me opportune moments to think.

Whilst my extrovert colleagues want to have that picnic in the park, I’m quite happy to sit in the garden. There lies another privilege. Simultaneously, I seldom feel the need to go out. Where I miss my cinema trips, I remember Netflix, Amazon Prime, Britbox and Disney+. Sure they’re not IMAX but they’ll do. I miss the pub but there’s the supermarket with all sorts of choices of IPA to choose from. Indeed, I have found solace in having my access stripped right back. The freedom to choose afforded to me because I work and live in a “developed country” (I use this term loosely).

For those of us that live in Britain, Coronavirus has swiftly shown that we live in a first-world country with a third-world healthcare system and levels of poverty – highly-skilled medical professionals in a perilously underfunded NHS systematically cut for the last ten years by the Tories.

Unlike University, I can mute social media for a couple of hours, and do some reading. I hate that I am so comfortable, whilst others are not. I often think about international students shafted by visa issues, and rough sleepers who don’t have the privilege of thinking about self-isolation. What about those having to self-isolate in tower blocks like Grenfell? What if we were to have another tragedy like Grenfell during a public health crisis? I hate how Coronavirus has exposed underlying inequalities, and how after this, these systems of power will likely carry on like it’s business as usual.

I don’t feel defeated or bored but the other inequalities in society do make me worry. Having been a victim of racism ten times over, both by individuals and institutions, I know that racism is its own disease and it won’t simply go on holiday because we’re in a pandemic. I know increasing police powers will disproportionately impact people from Black backgrounds, especially in working-class communities, but as Black people (pre-Coronavirus) at a rate of nine times more likely to be stopped and searched than a White person in Northamptonshire is bad enough, isn’t it?

This solitude has pushed me creatively with my poetry and own blogs. Take Eric Arthur Blair, or George Orwell as he was known; when he was sick with TB, he wrote Nineteen Eighty-Four. The book we now lord about today is essentially a first draft. Rushed. A last bout before death. In my isolation, I’m excited for the number of dystopian texts that will come out of Coronavirus, particularly political narratives on how Britain and America reacted. I’m looking forward to artistic expression and if the British public will hold the Government to account. One could argue their thoughtlessness, and support of genocide (herd immunity) is a state crime.

Whilst it is easy to blame the Chinese government, our own government have a lot to answer for and metaphorically speaking, someone (or quite a few people) need to hang.

A good friend and confidant has implored me to write a book as a project. Being naturally inward in my personality, I could do it. Though, I have my reservations. Perhaps I could write a work of genius that goes on to define a generation. Nonetheless, I observe that during lockdowns around the world, there will be both introverts and extroverts applying their minds to art and creativity. Writing books. Painting pictures. Discovering theories, like Isaac Newton did when he was “confined” to his estate during the Plague in 1665.

One day the curve will flatten: we will see each other again at the rising of the sun, folks say we must make use of this time; however, this is unprecedented, so it is also perfectly okay to be at peace with your loved ones, cherish those moments, and do absolutely nothing of consequence at all.

If Slavery is the crime, my surname’s the crime scene

As we reach the 180th anniversary of the emancipation for when the last slave was truly free in the British Empire, we must look at the legacy of the Slave Trade today. It can be seen in the names of many Black Britons from Caribbean backgrounds. Griffiths (Welsh) and Ventour (British-French), you cannot get more European than that. My names are proof that Britain and France took part in the oppression of my ancestors. They are part of my family history. And as Glasgow Councillor Graham Campbell says, “When you are part of the crime scene, you cannot let the evidence walk away.”

My brother’s visit to the International Slavery Museum in Liverpool with my mother brings it home. That in going there, for him it was slavery in black and white, literally. It showed that slavery didn’t discriminate by age. It impacted people from babies in their mother’s arms up to the elderly. I watched Roots for the first time at eight years old. And I will never forget Kunta Kinte saying his name. Desperately clinging on to the last piece of himself. His name. Not the name of the slave master. His African name.

In my exploration of my own names and their links with transatlantic slavery, I have seen I am the worst kind of person. When I ask a person I know to be Black British with a European-sounding last name about their names, what I’m doing is fishing on how they got that name. The fact that I know Black Britons whose last names are things like Richards, Smith or Francis. That on a CV, you would not know the colour of their skin based on their name. Speaking to many Black Britons, I find our slave-ridden past to be an uncomfortable topic, but it’s also a story that the White establishment in Britain would prefer to keep invisible out of the way.

The other day before Britain went into lockdown, I went to afternoon tea with some colleagues of mine from University. Being Black in those settings is strange in my opinion – an everyday thing that comes from colonial times, reminding me of big houses and slave plantations, and escapees would have their legs and feet amputated like Kunta Kinte. It reminds me of famine in Ireland and India, and the genocide of Indigenous Americans.

That when my ancestors were working under masters’ wrath, Master Ventour and Master Griffiths would be indulging in tea and cakes. In Britain we present colonialism as something to be proud of. That we went to these places as explorers and “civilised” the indigenous people, passing it off today as teaching them about English niceties, etiquette and table manners.

In my role at university, whenever I have encountered international students, I do my utmost to try to inform them of the history this country does not tell in its travel guides. That if they went on a tour of Trafalgar Square they would not learn that Admiral Nelson married a plantocrat’s daughter on a Nevitian slave plantation. That as part of the Royal Navy, it was his job to protect British commerce, including slave ships. We do not tell this history to holidaymakers or students in any real depth because it shows that our good etiquette and table manners are written in blood.

When I broach these subjects, I see people that just want this Black person to go back to whatever “shithole nation” he came from. Growing up, I was often silenced by my peers at school for talking about slavery. However, if you tried to silence the Jews for talking about The Holocaust or the Irish for talking about the Potato Famine, I am certain they would have something to say. For Black people, the Slave Trade is our Auschwitz and those sugar, tobacco and cotton plantations in the US and Caribbean were death camps.

Whilst there are more positive images of Black history we need to see, we cannot neglect the over two hundred years of British slavery. And if you walk around this country with its grandeur and National Trust stately homes, you will see the money of colonialism without the blood.

So, when you have the Windrush, along with their children and grandchildren living in the centre of colonial power, you are part of the crime scene and you can’t just walk away.

Black hair defies gravity: On Emma Dabiri's #DontTouchMyHair

In my role, I get emails from students about dissertations. One such student contacted me about how she was doing her dissertation on the political implications of Black hair on Black women / girls in education. Meeting this student in early February (I won’t name names), it really got me to think about the role of Black men in how Black women see themselves. Getting that message on Instagram showed me that even as a Black person, a man no less, I don’t have to think about myself in relation to my hair. That within the Black community there is a privilege.

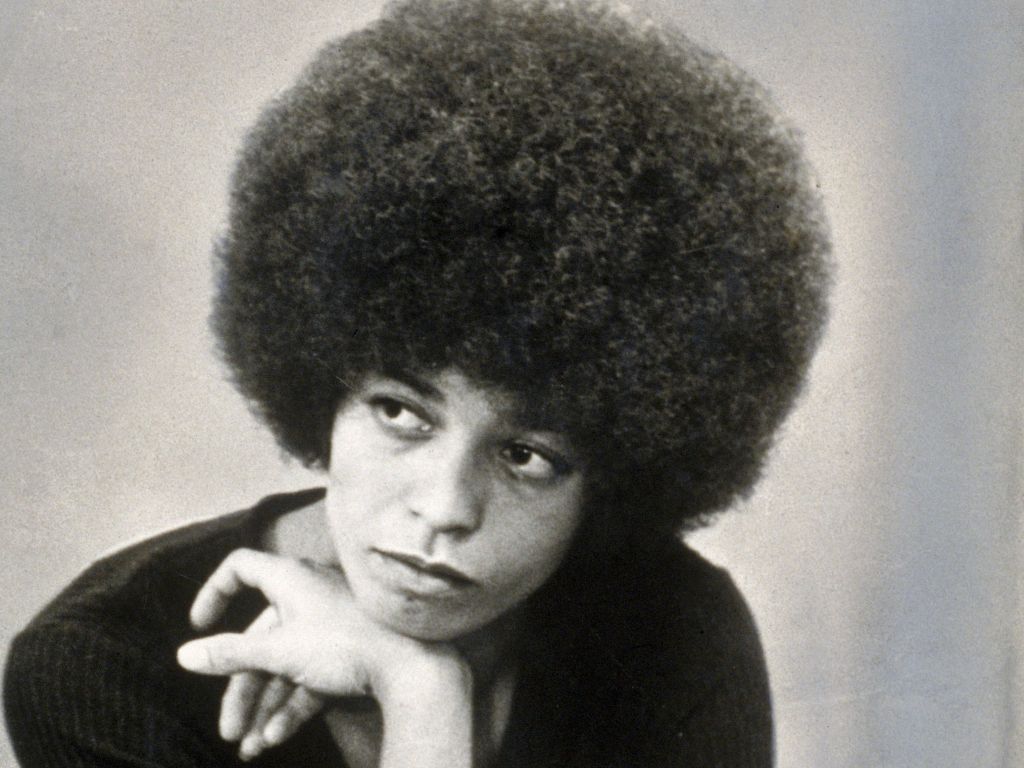

Don’t Touch My Hair by SOAS academic Emma Dabiri had been on my list for a long old time but my meeting with this student showed me I needed to fast track my reading of this text. We talked about Black hair historically, including the famous State of California vs Angela Davis in 1970 where she was on trial for kidnap and murder. Her hair out in true Black Panther fashion; whilst the FBI wanted to put her on trial, she put the FBI on trial.

Black hair is personal to Black people, especially women who I found growing up and even today working at a university with many in the student body, made to feel that it is “a constant source of deep deep shame” as said by Dabiri in her book. Having spoken to a few of Northampton’s Black female students about this, much of the criticism of hair does not come from White people (though they are also culpable), it comes from Black men whose own standards of beauty can often be European. Straight hair and lighter skin over Afro coils and darker skin.

Mixed-Race, though racialised as Black, from a White Trinidadian mother and Black Nigerian father, Emma Dabiri has tightly-coiled hair. Through Don’t Touch My Hair, she takes us on a tour of race and society; history, Black politics and White power and how they all have elements tied up together. It’s in the colouring, incl. oral storytelling, colonialism (and decolonisation), popular culture and cosmology.

Even as a youth, as one who would become a Black man, my own hair was donned “wild” and “unruly” by those who dictated what beauty looked like. I did a degree where we read books that described Black people as savages. Before we get to hair, Black bodies were shunned and hated, in: art, literature, films… going back to works of cinema like Birth of Nation often said to be responsible for resurgence of the Klu Klux Klan.

“To be white is to be human; to be white is universal, I only know because I am not.” – Reni Eddo-Lodge

“Straightened. Stigmatised. Tamed. Celebrated. Erased. Managed. Appropriated. Forever misunderstood. Black hair is never just hair.” For some their hair is part of their identity, and Black hair is ladened with history, culture, and politics. It’s a link between now and then. Dabiri details why Black hair matters in a series of chapters, from pre-colonial Africa to today’s Natural Hair Movement, as well as the Cultural Appropriation Wars.

I grew up around Black women who found solidarity in their hair. Afro hair. Braids. Twists. Dreadlocks. It was a celebration of their blackness, as was choosing to have my own hair long at school, might I add all-White private schools. For me to have my hair then was a political statement. It wasn’t until I came to University where I was introduced to young women who wore weave and wigs. Prior to that I had a childhood surrounded by people who wore it natural in the tint of shea butter and ‘Black people time.’

I ventured with White poets that had braids and dreadlocks. On one hand, I believe how can a hairstyle belong to a people? In the way of the artist, I didn’t challenge it. Why does appropriation exist? Dabiri showed why it’s so important. On the other hand, I recognised that to appropriate something as your own without acknowledgement is to steal history. She shows us that Black hairstyling varies from pop culture and cosmology to prehistoric times, to Afrofuturism (with Noughts and Crosses) and the blackness of the panther, alongside networks leading enslaved Africans to freedom.

Through her relating to the Nigerian ancestry on her father’s side, as well as the histories and stories of Black people in the United States, Britain and Latin America, she explore the history of Black hair and how we have been conditioned to relate to it. Wild. Unruly. High maintenance. Colonialism has done a number on Black people and those racialised as Black, depriving a whole people of any positive beauty standards, including hair history.

Choosing to talk positively about Black hair and changing the often discriminatory language (in itself) could be perceived as an act of decolonising, and if we are serious about decolonisation, we must look at language as well

You can tell this text was written by an academic, and true to form her sources are diverse. It was heartbreaking on my degree to have sources and texts that were whitewashed as much as race, and nearly dominated by men. As far as academia is concerned, I feel seen in Don’t Touch My Hair. That it shows people that look like me writing in their field, tying back to lack of Black representation in higher education, especially Black women.

From oral history to whitewashed British history, she points out the lack of representation and recognition of Black people in history books, regardless of their achievements in Science, Technology, Engineering and Maths [STEM]. Today, we are challenging universities to decolonise but Black students are tired of seeing themselves as stereotypes. There are other images we need to see, not just the same old same old. If Black children could see themselves as more than stereotypes, perhaps by the time they reach university they might have more self-identity as Black Britons.

Whilst this text is from the female perspective, I felt that representation. As a Black person who spent five days of every seven as a child around White people who didn’t have a clue about race issues, especially hair… I engaged with this book from beginning to end. English private schools don’t sound too dissimilar to the ignorance and racism Dabiri encountered in Ireland.

Photo Credit: Louise Stoner (2018)

As the only Black person at the schools I went to between the ages of eight and fourteen, many would find their hands wondering into my hair without consent. One of my favourite writers is Afua Hirsch. Like Emma Dabiri, Hirsch, also grew up mixed-race and wrote a book called Brit(ish) exploring her own identity, branching off into many subjects, including class.

Dabiri’s commentary on the “desire to conform” to a White “aesthetic which values lights skin and straight hair is the result of a propaganda campaign that last more than 500 years” is one I’m sure Black people everywhere relate to but will struggle to articulate. Coming through Britain’s private system, it’s one I struggled to avoid, as on more than one occasion my hair was compared to “wool” like I was Black in the war years, where they referred to “woolly-headed niggers” on British Army correspondence.

Emma Dabiri arrives at a time when the emerging generation of Black Britons are finding themselves lost in academia, writing dissertations on Black Britishness and seeing the deficit of texts that represent them – Don’t Touch My Hair is part of the revolution, and it defies gravity

Nobody prepared me for Coronavirus more than my grandparents

This might be the privilege of not living in a city or even being an essential worker but I have been (mostly) strangely calm through the Coronavirus pandemic. However, talking this through with a friend of mine, she noted that for Black people, many of our existences have revolved around survival since the Slave Trade and colonialism. The fact that I am so collected is that I derive from this history, but more so because I come from immigrants who are also working class who come from countries once colonised. Peoples that did whatever they had to do to survive. Here, is where race can also intersect with class, as the working-class can think in this state of “do or die” too.

As I wait out this self-isolation with the rest of the world, I am able live with the privilege of having a garden. I can go into the garden and watch the cats immediately scarper. I can sit out and have the sun rain on my face. Yet, Coronavirus shows how little regard many people have for the welfare of their neighbours. Whilst individually, you may not be showing symptoms, Joe Bloggs next door may be seventy-five years old in remission. Moreover, it has shown Coronavirus doesn’t discriminate. We are all human and we are all at risk, regardless of class, creed, faith, gender or social standing.

My maternal grandparents are both Windrush Generation from Grenada

Growing up under parents who themselves grew up under Caribbean parents, we share this survival mentality. That we expect to struggle. Not to remain complacent, even when we have gained something. Even as a pre-adolescent living on St. George’s Avenue in one of those houses, we still had this struggle mentality. All creatures are wired to survive, whatever it takes, but there is something special within Black Britons who are ourselves products of European colonial ambition, passed down the chain like genes.

Yet, trans-generational trauma runs rampant, families living in the aftermath of colonialism still with a you-have-to-struggle-otherwise-you-are-not-living-properly mentality

Coronavirus reminds me of how Black people, and other ethnicities who have past histories of colonial rule, specifically those living in the colonisers’ country were always ready for a pandemic because we live in a constant state of survival. Growing up British-Caribbean under members of the Windrush Generation, it’s hard not to notice that Caribbeans survived on things like rice dishes and soups, things that last. Moreover, buying items with long shelf lives, including canned goods, and marinading meats.

Is this a trait in all immigrant households? Is it a trait in working-class households? Is it a trait in households who come from stories of colonialism? I grew up with tough love, as my parents and my grandparents did before me, as did their forbears all the way back to the Slavery – where we toiled and died on sugar plantations under the lynch and the lash of masters’ wrath. To stock up on essential items is fundamentally Caribbean, and speaking to my African colleagues about this too, it’s like-for-like.

My mother tells me about when she grew up, that Wednesdays were “feast or famine day” (corned beef and rice) and Thursdays were fried bakes and eggs. Bacon and sausage (if you were lucky). When I see my grandmother wanting corn beef now, I had no idea this was considered “struggle food.” I grew up eating cornmeal porridge, always when I’d go to my Jamaican grandparents house in the West Midlands, and my Jamaican aunties’. Cornmeal is struggle food. When I read about the African-American experience, I read about how dishes like Grits came from American Slavery.

When I talk to my Black friends and family members around the world, they are united in the idea that they were always prepared for a pandemic, because they grew up the same way I did. In many African households, they use hard chicken for stews, yet I didn’t realise this came from thinking rooted in poverty. This is low quality chicken we were left with, historically.

Not that I didn’t know already but watching an episode of Black-ish on this brought it all home, that irrespective of class, many of the foods so ingrained in the cultures of Africa and the Caribbean are also go-to “struggle foods.”

My grandparents have always been stocked up on tinned goods for the 24 years I’ve known them. They’ve always been stocked on cleaning products. Heck, as child at my grandparents’, I would bathe in Dettol. You can fry dumplings and fish cakes (saltfish fritters) if there’s a bread shortage. But growing up, some of the looks I would recieve at the foods I would eat would now be labelled as micro-aggressive behaviour. That these foods are an overhang of Slavery… ground provisions made from animal scraps etc.

Curry goat with all the bones, Saturday soup, fried bakes, cow foot, pig tail, salted cod, fried plantain, cornmeal, oats porridge, rice and beans, and the list goes on. Mind you, I do not enjoy all these foods but colonialism laid the ground work. This is what makes decolonisation and postcolonialism interesting spaces. You have to ask yourself, where is the cut off point on whether it matters that “survival mentality” has been inherited from these systems of oppression and power? Moreover, is it wrong that they have been absorbed into cultures, assimilated as valid qualifiers in said cultures?

My experience of blackness is one as child of immigration, born and raise in Britain. As part of the Black diaspora in the UK. How do Africans born, raised and living in Africa see this? Or Caribbeans living on those small islands, where you can really see the heavy imprints left by colonial rule? In decolonisation, there are elements of cultures that are products of colonisation and therefore could be picked apart and critiqued, right?

Where is the line drawn between culture and colonialism? You begin to see how ingrained food is in culture, and it’s not so easy to trim through the fat of race, nor do people want to deconstruct the things they love and enjoy. I grew up in households where we told each other to “stay safe.” And the fact of the matter is the language of Coronavirus is the norm for many Black British people. “Stay Safe” – “Text me when home” – “Don’t walk that way.”

I have nobody to thank for my calmness during a pandemic more than my grandparents (and ancestors) as our histories are written as pandemics, it’s only now it’s effecting the lives of the super-rich that it’s now an institutional global crisis.

In ‘Clap For Our Carers’ we must #stopthewhitewash

In the documentation of #clapforourcarers, the British media does what Britain often does best, neglect its diversity whilst simultaneously boasting about diversity. You cannot tell the history of the NHS without talking about the diversity of ethnic backgrounds that make up the workforce. This history is also a story about race and society, incorporating the lives of people from around the world.

After the War, the UK government put out a call to its empire for workers, not thinking that all these Black and brown people from the Caribbean, and Asian and African continents would come, not the White people from English speaking countries such as New Zealand. The NHS would have been stillborn had it not been for Black nurses in the beginning that saved it from collapse. Yet, today, with Coronavirus, the whitewashing of the NHS continues in the media’s representation of the workforce. You cannot go to a hospital without running into the people of colour that keep it afloat.

The late Jamaican philosopher Stuart Hall said “We are here because you were there” and it is in part because of Britain’s colonial project that we have migrants from places all over the world. For international viewers looking in, watching British press on Coronavirus, they are being lead down this path of dominant whiteness. From the people being interviewed to how the NHS is being represented in the media. As Britons, we know the NHS workforce is culturally diverse. Yet, any viewers without knowledge of the NHS will believe that it is as White as it is being portrayed to be.

Africans, West Indians, Pakistanis, Indians, Chinese and many people of colour make up a good percentage of carers in Britain today. The same can be said for students on health-related courses at our universities including nursing, social work and social care. Like Gina Yashere says, it looks like Britain is erasing this diversity from its history. When we look back on this in 20 years time, history will show it to be whitewashed, as many significant events in British history were before it; from the world wars to Renaissance Britain to the days of Roman rule. But wasn’t it a legion of African Romans (or Moors) that stood watch on Hadrian’s Wall for nearly 350 years?

As I sit at home now in lockdown, we must talk about the nuances of Coronavirus under inequality. Will people of colour be stopped at a disproportionate rate to White people under new police powers? Will they be detained at such a rate? This is a global disease but those receiving tests seem to come from a certain class. We have a government that advocated for the genocide (herd immunity) of its ageing population. We also have a government that put the whims of billionaires over all. Its contempt for the working class has not gone unnoticed. When this is all over, the public and parliament needs to hold the prime minister’s government to account.

Gina Yashere mocks the people saying it shouldn’t be about race, and she’s absolutely right to do that. Race is a social construct but it’s a social construct of which the global majority have been othered. However, you cannot talk about British healthcare without talking about race. From institutional racism within healthcare to the diversity of the workforce. It comes from the comfort of privilege to live your life not having talk about race in any meaningful way. And life isn’t binary. One size doesn’t fit all.

We are better than this, we need to #stopthewhitewash; and if race doesn’t matter (as they say), why is the British media representing the National Health Service in its own image?

“My Favourite Things”: Tré

My favourite TV show - my favourite television series at the moment (since 2016) is The Hollow Crown, the BBC's adaptation of Shakespeare's history plays. It's an unparalleled television experience that makes Game of Thrones look like a garden party. My favourite place to go - I spend most Saturdays at the cinema, enjoying the art of storytelling. Film to me is what life is about. The person that doesn't engage in stories only lives one life. The person that reads, watches, writes, lives many. My favourite city - I don't feel that I'm at all that well-travelled and compared to my academic friends, I feel like I've lived in a bubble. From the few places I have been, I don't think I can choose just one. Mississauga, Canada (2018) was marvellous. I also grew up visiting my paternal family in Birmingham. I love Birmingham, it's like London without all the faffing about. My favourite thing to do in my free time - I live for films. I love watching old films, specifically films released pre-1970 where many were filmed in monochrome. I spend a lot of time at the cinema, even going to special event screenings of old films. My favourite athlete/sports personality - again, I'm an old soul. I don't think I can choose just one, so I would have to go for the iconic West Indies cricket team of 1980/81 that left Botham's England in the dirt. WI 5 - ENG 0. My favourite actor - Despite him doing some absolute oddballs these last few years, Robert DeNiro is still my favourite actor, being in some of the best films ever made, incl. The Godfather Part II, Once Upon a Time in America, Heat, Goodfellas and more. My favourite author - until recently my favourite author was Kathryn Stockett (The Help). However, I've come to reflect on the problematicness of this book. I think I would have to choose the late Andrea Levy who was voice to a whole generation of Black British Caribbeans through books like Small Island and Every Light in the House Burnin'. Truly a marvel who gave a voice to the Black British working-class and an inspiration to me as well. My favourite drink - It's been called an old man's drink but I'm an absolute sucker for a pint of IPA. If we were to go to the supermarket, I would go for Goose or Greene King. I guess it shows I have been spending too much time with my grandfather! My favourite food - curry goat, rice and peas with mac n cheese. Nothing else comes remotely close. It's the dish I grew up with. My favourite place to eat - Grandma's House. See above^^^ I like people who - who don't accept things at face value. Challenge themselves and their establishment. Ask the difficult questions and don't roll over. Many of my friends are activists and it shows, either through their writing as artists or taking it to the streets at anti-Brexit protests (for example). I don’t like it when people - claim to be authorities on things they know nothing about. Stop stroking your ego and step back. It's okay to say "I don't know enough about this to comment." I would actually think more of people if they did this. My favourite book - one of my favourite reads in the last few years is Carrie Pilby by Canadian novelist Caren Lissner. A charming young adult fiction story about a young woman trying to find her way in a world that doesn't relate to her. My favourite book character - I don't read enough fiction to answer this question genuinely. Recently, I'm inclined to go with Jaime Lannister from George R. R. Martin's A Song of Ice and Fire the series of books that went on to "loosely inspire" the American HBO television series Game of Thrones (2011 - 2019). My favourite film - Midnight in Paris, about an American writer stuck in what's called "Golden Age Thinking", the idea that a different time period is better than one you are living - and I don't think there's a person living that hasn't had this thought. However, when I do look to history, I think this is the best time to be people of colour; a woman; lesbian, gay, bi or trans; less able-bodied; the further back in history you look, the worse it looks for people who are not able-bodied White, straight men. My favourite poem - In recent years, I found Button Poetry where I was introduced to Canadian poet Sabrina Benaim. Her poem 'Explaining Depression to My Mother: A Conversation' struck a chord and continues to strike a chord to this day. My favourite artist/band - Bob Marley. If he had lived he would have been Prime Minister of Jamaica. Writer, artist, poet political activist, revolutionary. Legend. If he lived today, he would be standing alongside Jeremy Corbyn, Bernie Sanders and Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez in solidarity. And as we fight COVID-19, I'm sure he'd have something to say! Every song is mega, and Natty Dread (1974) is one of the best albums ever made. My favourite song - London Bridge (1980) by The Mighty Sparrow is certainly one of my favourite. Written in time of of unrest in England, this is a commentary on English history and society. What's more, this is calypso music from my maternal grandparents' country, Grenada. Caribbean music is battlefield music and The Mighty Sparrow is one of our countrymen sticking it to our former-colonial masters in a way that's jovial and lively. My favourite art - I'm partial to Vincent van Gogh's Sunflowers. Its stillness reminds me the world isn't all fast-paced and sometimes we have to take a moment to reflect. My favourite person from history - one of my favourite historical figures is Black mixed-race footballer-turned-soldier Walter Tull. It is safe to say I would not be where I am had it not been for Walter Tull. He is a testament to what can be achieved, irrespective of hostile environments. Moreover, not only is he a testament to all men but is a role model to Black men in 2020. Not only was he one of the first Black footballers in England, he was the first Black officer in the British Army at a time when it was illegal for "men of non-European descent" to lead White men. Walter is part of Black history, Northampton history, but above of all, my history and I am extremely proud of that.