Home » Articles posted by manosdaskalou (Page 9)

Author Archives: manosdaskalou

Is Easter a criminological issue?

Spring is the time that many Christians relate with the celebration of Easter. For many the sacrament of Easter seals their faith; as in the end of torment and suffering, there is the resurrection of the head of the faith. All these are issues to consider in a religious studies blog and perhaps consider the existential implications in a philosophical discourse. How about criminology?

In criminology it provides great penological and criminological lessons. The nature of Jesus’s apprehension, by what is described as a mob, relates to ideas of vigilantism and the old non-professional watchmen who existed in many different countries around the world. The torture, suffered is not too dissimilar from the investigative interrogation unfortunately practiced even today around the world (overtly or covertly). His move from court to court, relates to the way we apply for judicial jurisdiction depending on the severity of the case and the nature of the crime. The subsequent trial; short and very purposefully focused to find Jesus guilty, is so reminiscent of what we now call a “kangaroo court” with a dose of penal appeasement and penal populism for good measure. The final part of this judicial drama, is played with the execution. The man on the cross. Thousands of men (it is not clear how many) were executed in this method.

For a historian the exploration of past is key, for a legal professional the study of black letter law principles and for a criminal justice practitioner the way methods of criminal processes altered in time. What about a reader in criminology? For a criminologist there are wider meanings to ascertain and to relate them to our fundamental understanding of justice in the depth of time. The events which unfolded two millennia back, relate to very current issues we read in the news and study in our curriculum. Consider arrest procedures including the very contested stop and search practice. The racial inequalities in court and the ongoing debates on jury nullification as a strategy to combat them. Our constant opposition as a discipline to the use of torture at any point of the justice system including the use of death penalty. In criminology we do not simply study criminal justice, but equally important, that of social justice. In a recent talk in response to a student’s question I said that that at heart of each criminologist is an abolitionist. So, despite our relationship and work with the prison service, we remain hopeful for a world where the prison does not become an inevitable sentence but an ultimate one, and one that we shall rarely use. Perhaps if we were to focus more on social justice and the inequalities we may have far less need for criminal justice

Evidently Easter has plenty to offer for a criminologist. As a social discipline, it allows us to take stock and notice the world around us, break down relationships and even evaluate complex relationships defying world belief systems. Apparently after the crucifixion there was also a resurrection; for more information about that, search a theological blog. Interestingly in his Urbi et Orbi this year the Pope spoke for the need for world leaders to focus on social justice.

Modern University or New University?

As I am outside the prison walls on another visit I look at the high walls that keep people inside incarcerated. This is an institution designed to keep people in and it is obvious from the outside. This made me wonder what is a University designed for? Are we equally obvious to the communities in which we live as to what we are there for? These questions have been posed before but as we embark in a new educational environment I begin to wonder.

There are city universities, campuses in towns and the countryside, new universities and of course old, even, medieval universities. All these institutions have an educational purpose in common at a high level but that is more or less it. Traditionally, academia had a specific mandate of what they were meant to be doing but this original focus was coming from a era when computers, the electronic revolution and the knowledge explosion were unheard of. I still amuse my students by my recollections of going through an old library, looking at their card catalogue in order to find the books I wanted for my essay.

Since then, email has become the main tool for communication and blackboard or other virtual learning environments are growing into becoming an alternative learning tool in the arsenal of each academic. In this technologically advanced, modern world it is pertinent to ask if the University is the environment that it once was. The introduction of fees, and the subsequent political debates on whether to raise the fees or get rid of them altogether. This debate has also introduced an consumerist dimension to higher education that previous learners did not encounter. For some colleagues this was a watershed moment in the mandate of higher education and the relationship between tutor and tutee. Recently, a well respected colleague told me how inspired she was to pursue a career in academia when she watched Willy Russell’s theatrical masterpiece Educating Rita. It seems likely that this cultural reference will be lost to current students and academics. A clear sign of things moving on.

So what is a University for in the 21st century? In my mind, the university is an institution of education that is open to its community and accessible to all people, even those who never thought that Higher Education is for them. Physically, there may not be walls around but for many people who never had the opportunity to enjoy a higher education, there may be barriers. It is perhaps the purpose of the new university to engage with the community and invite the people to embrace it as their community space. Our University’s relocation to the heart of the town will make our presence more visible in town and it is a great opportunity for the University to be reintroduced to the local community. As one of the few Changemaker universities in the country, a title that focuses on social change and entrepreneurship, connecting with the community is definitely a fundamental objective. In this way it will offer its space up for meaningful discussions on a variety of issues, academic or not, to the community saying we are a public institution for all. After all, this is part of how we understand criminology’s role. In a recent discussion we have been talking about criminology in the community; a public criminology. One of the many reasons why we work so hard to teach criminology in prisons.

The true message of Christmas

One of the seasonal discussions we have at social fora is how early the Christmas celebrations start in the streets, shops and the media. An image of snowy landscapes and joyful renditions of festive themes that appear sometime in October and intensify as the weeks unforld. It seems that every year the preparations for the festive season start a little bit earlier, making some of us to wonder why make this fuss? Employees in shops wearing festive antlers and jumpers add to the general merriment and fun usually “enforced” by insistent management whose only wish is to enhance our celebratory mood. Even in my classes some of the students decided to chip in the holiday fun wearing oversized festive jumpers (you know who you are!). In one of those classes I pointed out that this phenomenon panders to the commercialisation of festivals only to be called a “grinch” by one of the gobby ones. Of course all in good humour, I thought.

Nonetheless it was strange considering that we live in a consumerist society that the festive season is marred with the pressure to buy as much food as possible so much so, that those who cannot (according to a number of charities) feel embarrassed to go shopping; or the promotion of new toys, cosmetics and other trendy items that people have to have badly wrapped ready for the big day. The emphasis on consumption is not something that happened overnight. There have been years of making the special season into a family event of Olympic proportions. Personal and family budgets will dwindle in the need to buy parcels of goods, consume volumes of food and alcohol so that we can rejoice.

Many of us by the end of the festive season will look back with regret, for the pounds we put on, the pounds we spent and the things we wanted to do but deferred them until next Christmas. Which poses the question; What is the point of the holiday or even better, why celebrate Christmas anymore? Maybe a secular society needs to move away from religious festivities and instead concentrate on civic matters alone. Why does religion get to dictate the “season to be jolly” and not people’s own desire to be with the ones they want to be with? If there is a message within the religious symbolism this is not reflected in the shop-windows that promote a round-shaped old man in red, non-existent (pagan) creatures and polar animals.

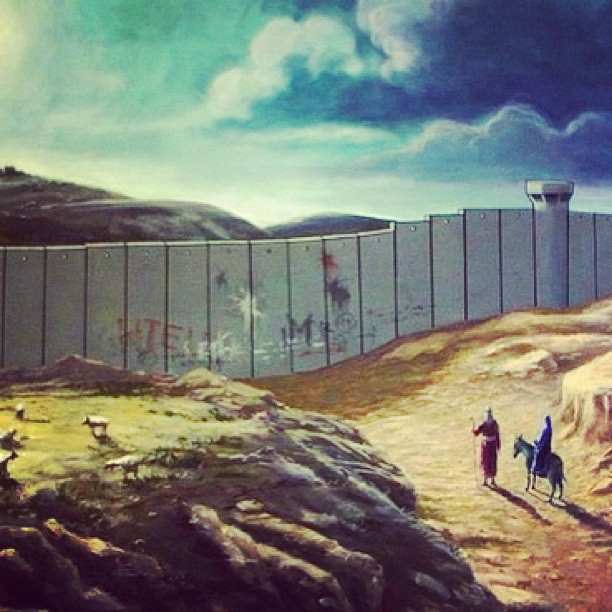

According to the religious message about 2000 years ago a refugee family gave birth to a child on their way to exile. The child would live for about 33 years but will change the face of modern religion. He promised to come back and millions of people still wait for his second coming but in the meantime millions of refugee children are piling up in detention centers and hundreds of others are dying in the journey of the damned. “A voice is heard in Ramah, mourning and great weeping, Rachel weeping for her children, because her children are no more” (Jeremiah 31:15). This is the true message of Christmas today.

Happy Holidays to our students and colleagues.

FYI: Ramah is a town in war torn Middle East

Leave my country

One image, one word, one report can generate so much emotion and discussion. The image of the naked girl running away from a napalm bombed village, the word “paedo” used in tabloids to signal particular cases and reports such as the Hillsborough or the Lamy reports which brought centre stage major social issues that we dare not talk about.*

Regardless of the source, it is those media that make a cultural statement making an impact that in some cases transcends their time and forms our collective consciousness. There are numerous images, words and reports, and we choose to make some of these symbols that explain our theory of the world around us.

It was in the news that I saw a picture of a broken window, a stone and a sign next to it: “Leave my country”. The sign was held by an 11 year old refugee with big brown eyes asking why. This is not the only image that made it to the news this week; some days ago following the fatal car crash in New York the image of a 29 year old suspect from Uzbekistan appeared everywhere. These two images are of course unconnected across continents and time but there is some semiology worth noting.

We make sense of the world around us by observing. It is the media that are our eyes helping us to explore this wider world and witness relationships, events and situations that we may never considered possible. It must have been a very different world when over a century ago news of the sinking of the Titanic came through. We store images and words that help us define the way our world functions. In criminology, words are always attached to emotion and prejudice.

I deliberately chose two images: a victimised child and an adult suspect of an act of terror. They have nothing in common other than both appear foreign in the way I understand those who are not like me. Of course neither of these images is personally relatable to me but their story is compelling for different reasons. Then of course as I explore both stories and images, I wonder what is that remains of my understanding of the foreigner?

Last year, the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo produced a caricature of what would little Aylan would have done if he was to grow up, presented as a sex pest. The caricature caused public outcry but at the time, like this week, I started considering the images and their meanings. Do we put stories together based on the images we see around us? If that is a way of defining and explaining our social world then the imagery of good and bad foreigners, young and old, victims and villains may merge in a deconstruction of social reality that defines the foreigner. In that case and at that point the sign next to the 11 year old may not be voiced but it can become an implicit collective objective.

*At this stage I would like to mention that I was considering to write about the media’s “surprise” over the abuse allegations following revelations for a Hollywood producer but decide not to, due to the media’s attempt to saturate one of the most significant social issues of our times with other studies with varying levels of credibility. We observed a similar situation after the Jimmy Saville case.

The Criminology of the Future

As we are gleefully coming towards the start of yet another academic year, we tend to go through a number of perpetual motions; reflect on the year past, prepare material for the upcoming year and make adjustments on current educational expectations. Academics can be creatures of habit, even if their habit is to change things over. Nonetheless, there are always milestones that we all observe no matter the institution or discipline. The graduation, for example brings to an end the degree aspirations of a cohort, whilst Clearing and Welcome Week offer an opportunity of a new group of applicants to join a cohort and begin the process again. Academia like a pendulum swings constantly, replenishing itself with new generations of learners who carry with them the imprint of their social circumstance.

It was in the hectic days at Clearing that my mind began to wonder about the future of education and more importantly about criminology. A discipline that emerged at an unsettled time when urban life and modernity began to dominate the Western landscape. Young people (both in age and/or in spirit) began to question traditional notions about the establishment and its significance. The boundaries that protect the individual from the whim of the authorities was one of those fundamental concerns on criminological discourses. A 19th century colleague questions the notion of policing as an established institution, thus challenging its authority and necessity. An end of 20th century colleague may be involved in the training of those involved in policing. Changing times, arguably. Quite; but what is the implications for the discipline?

My random example can be challenged on many different fronts; the contested nature of a colleague as a singular entity that sees the world in a singular gaze; or the ability to diversify on the perspectives each discipline observes. It does nonetheless, raises a key question: what expectations can we place on the discipline for the 21st century.

If we and our students are the participants of social change as it happens in our society then our impressions and experiences can help us formulate a projective perspective of the future. Our knowledge of the past is key to supplying an understanding of what we have done before, so that we can comprehend the reality in a way that will allow us to give it the vocabulary it deserves. A colleague recently posted on twitter her agony about “vehicles being the new terrorist weapon,” asking what is the answer. The answer to violence is exactly the same; whether a person gets in a van, or goes home and uses a bread knife to harm their partner. Everyday objects that can be utilised to harm. A projection in the future could assert that this phenomenon is likely to continue. The Romans called it Alea iacta est and it was the moment you decide to act. In my heart this is precisely the debate about the future of criminology; is it crime with or without free will?

Terrorism? No thank you

Recent terrorist attacks in Manchester and the capital, like others that happened in Europe in recent years, made the public focus again on commonly posed questions about the rationale and objectives of such seemingly senseless acts. From some of the earliest texts on Criminology, terrorism has been viewed as one of the most challenging areas to address, including defining it.

There is no denial that acts, such as those seen across the world, often aimed at civilian populations, are highly irrational. It is partly because of the nature of the act that we become quite emotional. We tend question the motive and, most importantly, the people who are willing to commit such heinous acts. Some time ago, Edwin Sutherland, warned about the development of harsh laws as a countermeasure for those we see as repulsive criminals. In his time it was the sexual deviants; whilst now we have a similar feeling for those who commit acts of terror. We could try to apply his theory of differential association to explain some terrorist behaviours. however it cannot explain why these acts keep happening again and again.

At this point, it is rather significant to mention that terrorism (and whatever we currently consider acts of terror) is a fairly old phenomenon that dates back to many early organised and expansionist societies. We are not the first, and unfortunately not the last, to live in an age of terror. Reiner, a decade ago, identified terrorism as a vehicle to declare crime as “public enemy number 1 and a major threat to society” (2007: 124). In fact, the focus on individualised characteristics of the perpetrator detract from any social responsibility leading to harsher penalties and sacrifices of civil liberties almost completely unopposed. As White and Haines write, “the concern for the preservation of human rights is replaced by an emphasis on terrorism […] and the necessity to fight them by any means necessary” (1996: 139).

For many old criminologists who forged established concepts in the discipline, to simply and totally condemn terrorism, is not so straightforward. Consider for example Leon Radzinowicz (1906-1999) who saw the suppression of terror as the State’s attempt to maintain a state of persecution. After all, many of those who come from countries that emerged in the 19th and 20th centuries probably owe their nationhood to groups of people originally described as terrorists. This of course is the age old debate among criminologists “one man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter”. Many, of course, question the validity of such a statement at a time when the world has seen an unprecedented number of states make a firm declaration to self-determination. That is definitely a fair point to make, but at the same time we see age-old phenomena like slavery, exploitation and suppression of individual rights to remain prevalent issues now. People’s movements away from hotbeds of conflict remain a real problem and Engels’ (1820- 1895) observation about large cities becoming a place of social warfare still relevant.

Reiner R (2007), Law and Order, an honest citizen’s guide to crime and control, Cambridge, Polity Press

White R and Haines F (1996), Crime and Criminology, Oxford, Oxford University Press

The criminology of real life

Ever since I joined academia as a criminology lecturer, I found the question asked “what do you do” to be one that is followed by further questions. The role or rather title of a criminologist is one that is always met with great curiosity. Being a lecturer is a general title that most people understand as a person who does lectures, seminars, tutorials and workshops, something akin to a teacher. But what does a criminology lecturer do? Talks about crime presumably…but do they understand criminals? And more to the point, how do they understand them?

The supposed reading of the criminal mind is something that connects with the collective zeitgeist of our time. Some of our colleagues have called this the CSI factor or phenomenon. A media portrayal of criminal investigation into violent crime, usually murder, that seems to follow the old whodunit recipe sprinkled with some forensic science with some “pop” psychology on the side. The popularity of this phenomenon is well recorded and can easily be demonstrated by the numerous programmes which seemingly proliferate. I believe that there are even television channels now devoted completely to crime programmes. Here, it would be good to point out that it is slightly hypocritical to criticise crime related problems when some of us, on occasion, enjoy a good crime dramatisation on paper or in the movies.

Therefore I understand the wider interest and to some degree I expect that in a society dominated with mass and social media, people will try to relate fiction with academic expertise. In fact, in some cases I find it quite interesting as a contemporary tool of social conversation. You can have for example, hours of discussion about profiling, killers and other crimes with inquisitive taxi-drivers, border-control officers, hotel managers etc. They ask profession, you respond “criminologist” and you can end up having a long involving conversation about a programme you may have never seen.

There is however, quite possibly a personal limitation, a point where I draw the line. This is primarily when I get asked about particular people or current live crime cases. In the first year I talk to our students about the Soham murders. A case that happened close to 15 years ago now. What I have not told the students before, is the reason I talk about the case.

Fifteen years ago I was returning from holiday and I took a taxi home. The taxi driver, once he heard I was a criminology lecturer, asked me about the case. I remember this conversation as the academic and the everyday collided. He could not understand why I could not read the criminal intentions of the “monsters” who did what they did. To him, it was so clear and straightforward and therefore my inability to give him straight answers was frustrating. I thought about it since and of course other situations in similar criminal cases that I have been asked about. Why do people want complete and direct answers to the most complex of human behaviours?

One of the reasons that there is a public expectation to be able to talk about individual cases rests on the same factor that makes crime popular; its media portrayal. The way we collectively respond to real crime cases reflects a popularised dramatisation. So, this is not just a clash between academic and lay, but reality and fiction.

About a year ago, as a team we started this blog in order to relate criminological ideas into everyday life. News, events and markers on our social calendar became sources of inspiration and inquiry. Within a year, we have managed somehow to reflect on the academic cycle, some pretty heavy social issues that evoked our passions and interests. Those of you who read our entries, thank you for taking the time, especially those who left comments with your own experiences and ideas.

About a year ago, as a team we started this blog in order to relate criminological ideas into everyday life. News, events and markers on our social calendar became sources of inspiration and inquiry. Within a year, we have managed somehow to reflect on the academic cycle, some pretty heavy social issues that evoked our passions and interests. Those of you who read our entries, thank you for taking the time, especially those who left comments with your own experiences and ideas.