Home » Posts tagged 'Law'

Tag Archives: Law

Exploring the National Museum of Justice: A Journey Through History and Justice

As Programme Leader for BA Law with Criminology, I was excited to be offered the opportunity to attend the National Museum of Justice trip with the Criminology Team which took place at the back end of last year. I imagine, that when most of us think about justice, the first thing that springs to mind are courthouses filled with judges, lawyers, and juries deliberating the fates of those before them. However, the fact is that the concept of justice stretches far beyond the courtroom, encompassing a rich tapestry of history, culture, and education. One such embodiment of this multifaceted theme is the National Museum of Justice, a unique and thought-provoking attraction located in Nottingham. This blog takes you on a journey through its historical significance, exhibits, and the essential lessons it imparts and reinforces about justice and society.

A Historical Overview

The National Museum of Justice is housed in the Old Crown Court and the former Nottinghamshire County Gaol, which date back to the 18th century. This venue has witnessed a myriad of legal proceedings, from the trials of infamous criminals to the day-to-day workings of the justice system. For instance, it has seen trials of notable criminals, including the infamous Nottinghamshire smuggler, and it played a role during the turbulent times of the 19th century when debates around prison reform gained momentum. You can read about Richard Thomas Parker, the last man to be publicly executed and who was hanged outside the building here. The building itself is steeped in decade upon decade of history, with its architecture reflecting the evolution of legal practices over the centuries. For example, High Pavement and the spot where the gallows once stood.

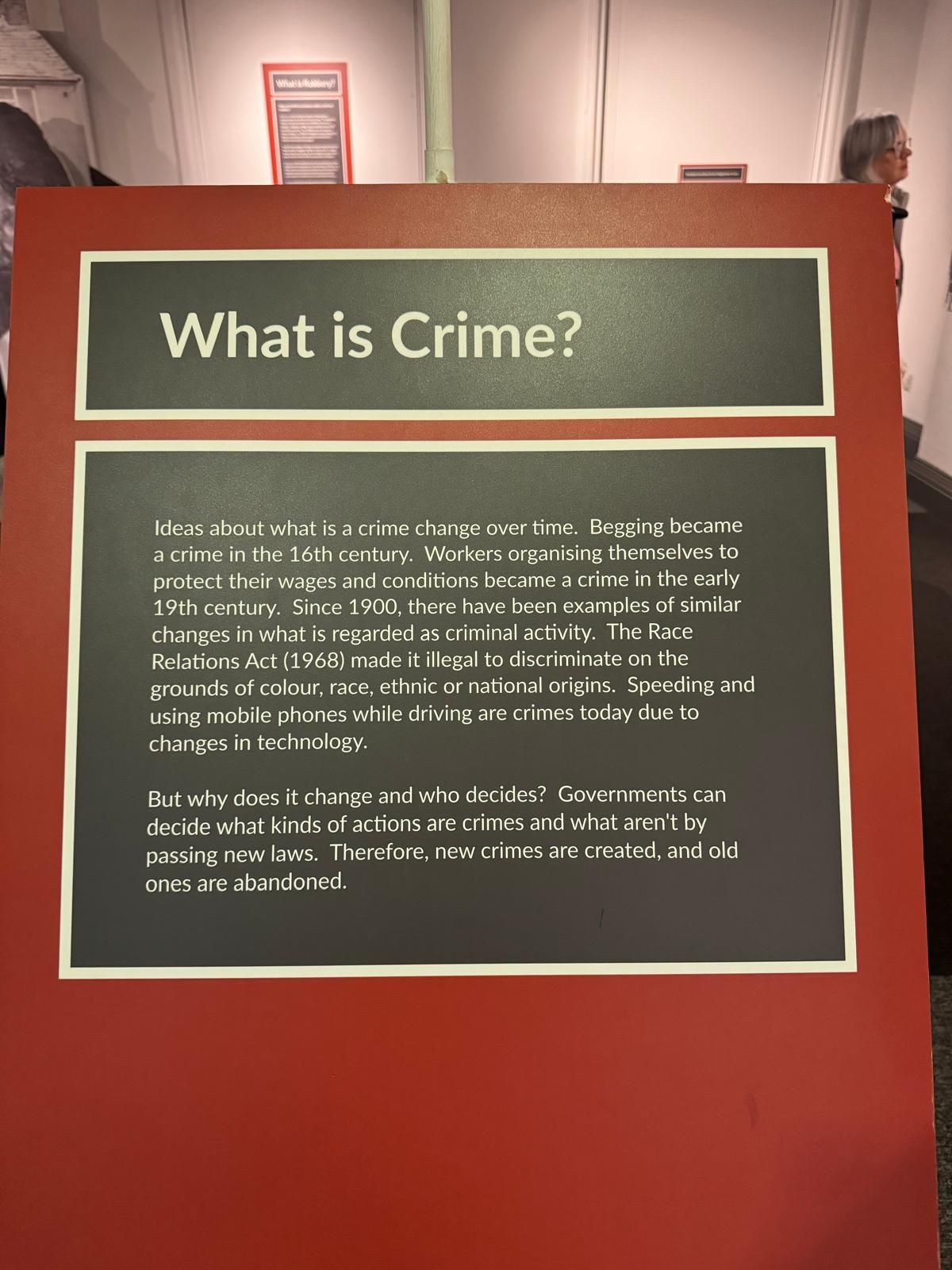

By visiting the museum, it is possible to trace the origins of the British legal system, exploring how societal values and norms have shaped the laws we live by today. The National Museum of Justice serves as a reminder that justice is not a static concept; it evolves as society changes, adapting to new challenges and perspectives. For example, one of my favourite exhibits was the bench from Bow Street Magistrates Court. The same bench where defendants like Oscar Wilde, Mick Jagger and the Suffragettes would have sat on during each of their famous trials. This bench has witnessed everything from defendants being accused of hacking into USA Government computers (Gary McKinnon), Gross Indecency (Oscar Wilde), Libel (Jeffrey Archer), Inciting a Riot (Emmeline Pankhurst) as well as Assaulting a Police Officer (Miss Dynamite).

Understanding this rich history invites visitors to contextualize the legal system and appreciate the ongoing struggle for a just society.

Engaging Exhibits

The National Museum of Justice is more than just a museum; it is an interactive experience that invites visitors to engage with the past. The exhibits are thoughtfully curated to provide a comprehensive understanding of the legal system and its historical context. Among the highlights are:

1. The Criminal Courtroom: Step into the courtroom where real trials were once held. Here, visitors can learn about the roles of various courtroom participants, such as the judge, jury, and barristers. This is the same room that the Criminology staff and students gathered in at the end of the day to share our reflections on what we had learned from our trip. Most students admitted that it had reinforced their belief that our system of justice had not really changed over the centuries in that marginalised communities still were not dealt with fairly.

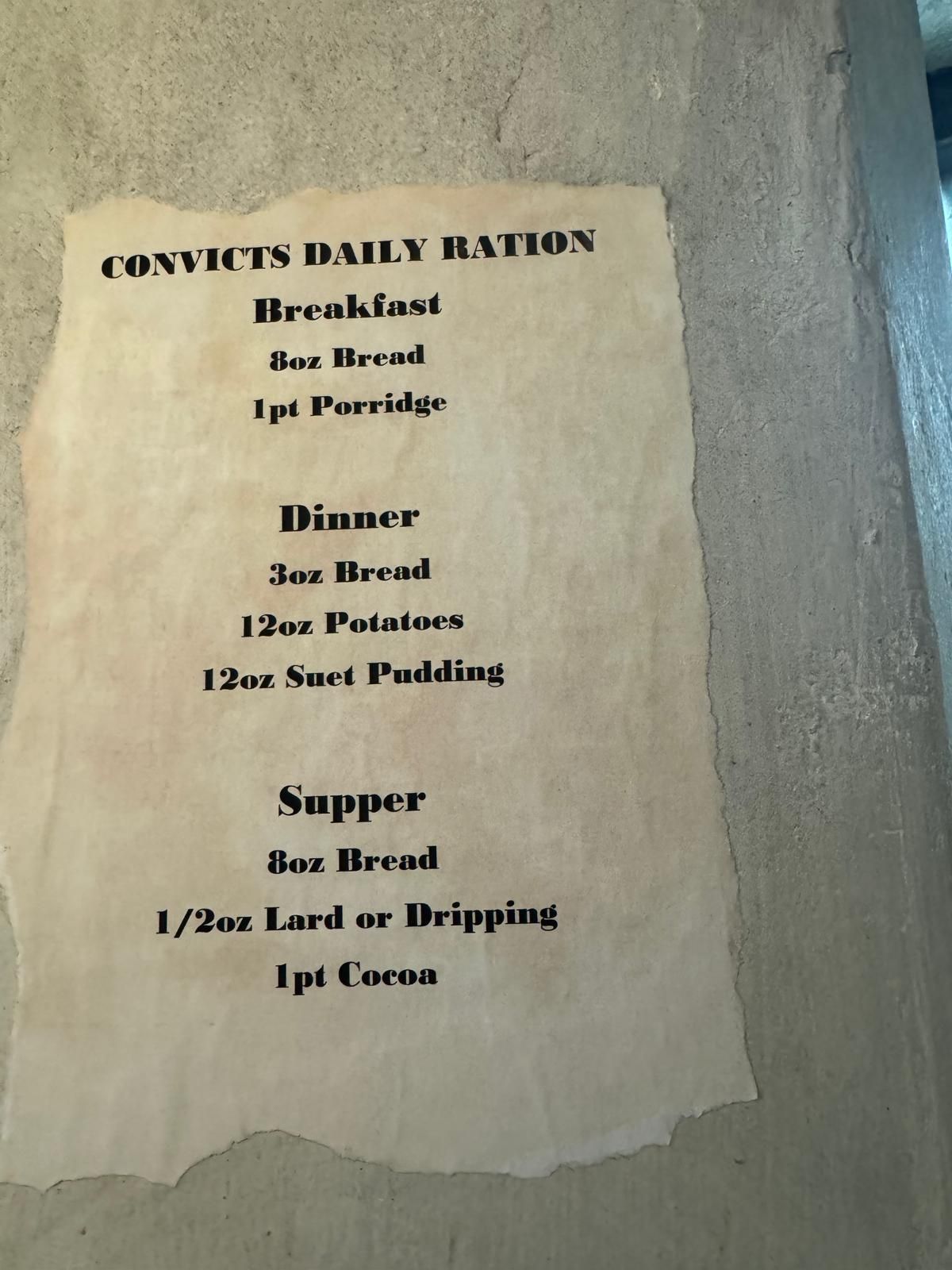

2. The Gaol: We delved into the grim reality of life in prison during the Georgian and Victorian eras. The gaol section of the gallery offers a sobering look at the conditions inmates faced, emphasizing the societal implications of punishment and rehabilitation. For example, every prisoner had to pay for his/ her own food and once their sentence was up, they would not be allowed to leave the prison unless all payments were up to date. The stark conditions depicted in this exhibit encourage reflections on the evolution of prison systems and the ongoing debates surrounding rehabilitation versus punishment. Eventually, in prisons, women were taught skills such as sewing and reading which it was hoped may better their chances of a successful life in society post release. This was an evolution within the prison system and a step towards rehabilitation of offenders rather than punishment.

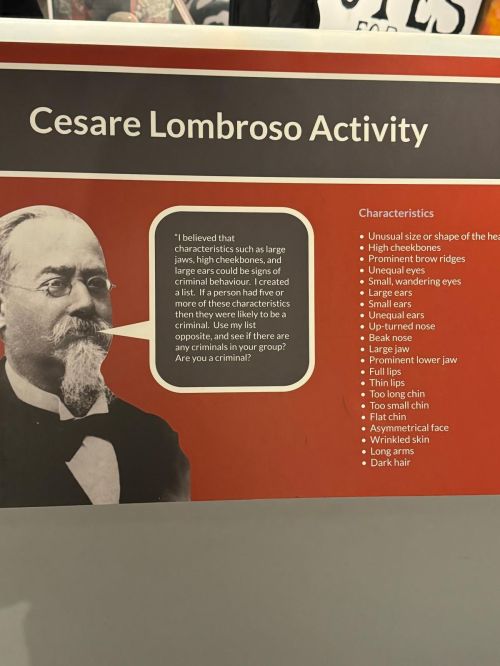

3. The Crime and Punishment Exhibit: This exhibit examines the relationship between crime and society, showcasing the changing perceptions of criminal behaviour over time. For example, one famous Criminologist of the day Cesare Lombroso, once believed that it was possible to spot a criminal based on their physical appearance such as high cheekbones, small ears, big ears or indeed even unequal ears. Since I was not familiar with Lombroso or his work, I enquired with the Criminology department as to studies that he used to reach the above conclusions. Although I believe he did carry out some ‘chaotic’ studies, it really reminded me that it is possible to make statistics say whatever it is you want them to say. This is the same point in relation to the law generally. As a lawyer I can make the law essentially say whatever I want it to say in the way I construct my arguments and the sources I include. Overall, The Inclusions of such exhibits raises and attempts to tackle difficult questions about personal and societal morality, justice, and the impact of societal norms on individual actions. By examining such leading theories of the time and their societal reactions, the exhibit encourages visitors to consider the broader implications of crime and the necessity of reform within the justice system. Do you think that today, deciding whether someone is a criminal based on their physical appearance would be acceptable? Do we in fact still do this? If we do, then we have not learned the lessons from history or really moved on from Cesare Lombroso.

Lessons on Justice and Society

The National Museum of Justice is not merely a historical site; it also serves as a platform for discussions about contemporary issues related to justice. Through its exhibits and programs, our group was invited to reflect on essentially- The Evolution of Justice: Understanding how laws have changed (or not!) over time helps us appreciate the progress (or not!) made in human rights and justice and with particular reference to women. It also encourages us to consider what changes may still be needed. For example, we were incredibly privileged to be able to access the archives at the museum and handle real primary source materials. We, through official records followed the journey of some women and girls who had been sent to reform schools and prisons. Some were given extremely long sentences for perhaps stealing a loaf of bread or reel of cotton. It seemed to me that just like today, there it was- the huge link between poverty and crime. Yet, what have we done about this in over two or three hundred years? This focus on historical cases illustrates the importance of learning from the past to inform present and future legal practices.

– The Importance of Fair Trials: The gallery emphasizes the significance of due process and the presumption of innocence, reminding us that justice must be impartial and equitable. In a world where public opinion can often sway perceptions of guilt or innocence, this reminder is particularly pertinent. The National Museum of Justice underscores the critical role that fair trials play in maintaining the integrity of the legal system. For example, if you were identified as a potential criminal by Cesare Lombroso (who I referred to above) then you were probably not going to get a fair trial versus an individual who had none of the characteristics referred to by his studies.

– Societal Responsibility: The exhibits prompt discussions about the role of society in shaping laws and the collective responsibility we all share in creating a just environment. The National Museum of Justice encourages visitors to think about their own roles in advocating for justice, equality, and reform. It highlights that justice is not solely the responsibility of legal professionals but also of the community at large.

– Ethics and Morality: The museum offers a platform to explore ethical dilemmas and moral questions surrounding justice. Engaging with historical cases can lead to discussions about right and wrong, prompting visitors to consider their own beliefs and biases regarding justice.

Conclusion

The National Museum of Justice in Nottingham is a remarkable destination that beautifully intertwines history, education, and advocacy for justice. By exploring its rich exhibits and engaging with its thought-provoking themes, visitors gain a deeper understanding of the complexities surrounding justice and its vital role in society. Whether you are a history buff, a legal enthusiast, a Criminologist or simply curious about the workings of justice, the National Museum of Justice offers a captivating journey that will leave you enlightened and inspired.

As we navigate the complexities of the modern world, it is essential to remember the lessons of the past and continue striving for a fair and just society for all. The National Museum of Justice stands as a powerful testament to the ongoing quest for justice, inviting us all to be active participants in that journey. In doing so, we honour the legacy of those who have fought for justice throughout history and commit ourselves to ensuring that the principles of fairness and equity remain at the forefront of our society. Sitting on that same bench that Emmeline Pankhurst once sat really reminded me of why I initially studied law.

The main thought that I was left with as I left the museum was that justice is not just a concept; it is a lived experience that we all contribute to shaping.

SUPREME COURT VISIT WITH MY CRIMINOLOGY SQUAD!

Author: Dr Paul Famosaya

This week, I’m excited to share my recent visit to the Supreme Court in London – a place that never fails to inspire me with its magnificent architecture and rich legal heritage. On Wednesday, I accompanied our final year criminology students along with my colleagues Jes, Liam, and our department head, Manos, on what proved to be a fascinating educational visit. For those unfamiliar with its role, the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom stands at the apex of our legal system. It was established in 2009, and serves as the final court for all civil cases in the UK and criminal cases from England, Wales, and Northern Ireland. From a criminological perspective, this institution is particularly significant as it shapes the interpretation and application of criminal law through precedent-setting judgments that influence every level of our criminal justice system

7:45 AM: Made it to campus just in the nick of time to join the team. Nothing starts a Supreme Court visit quite like a dash through Abington’s morning traffic!

8:00 AM: Our coach is set to whisk us away to London!

Okay, real talk – whoever designed these coach air conditioning systems clearly has a vendetta against warm-blooded academics like me! 🥶 Here I am, all excited about the visit, and the temperature is giving me an impromptu lesson in ‘cry’ogenics. But hey, nothing can hold us down!.

Picture: Inside the coach where you can spot the perfect mix of university life – some students chatting about the visit, while others are already practising their courtroom napping skills 😴

There’s our department Head of Departmen Manos, diligently doing probably his fifth headcount 😂. Big boss is channelling his inner primary school teacher right now, armed with his attendance sheet and pen and all. And yes, there’s someone there in row 5 I think, who’s already dozed off 🤦🏽♀️ Honestly, can’t blame them, it’s criminally early!

9:05 AM The dreaded M1 traffic

Sometimes these slow moments give us the best opportunities to reflect. While we’re crawling through, my mind wanders to some of the landmark cases we’ll be discussing today. The Supreme Court’s role in shaping our most complex moral and legal debates is fascinating – take the assisted dying cases for instance. These aren’t just legal arguments; they’re profound questions about human dignity, autonomy, and the limits of state intervention in deeply personal decisions. It’s also interesting to think about how the evolution of our highest court reflects (or sometimes doesn’t reflect) the society it serves. When we discuss access to justice in our criminology lectures, we often talk about how diverse perspectives and lived experiences shape legal interpretation and decision-making. These thoughts feel particularly relevant as we approach the very institution where these crucial decisions are made.

The traffic might be testing our patience, but at least it’s giving us time to really think about these issues.

10:07 AM – Arriving London – The stark reality of London’s inequality hits you right here, just steps from Hyde Park.

Honestly, this is a scene that perfectly summarises the deep social divisions in our society – luxury cars pulling up to the Dorchester where rooms cost more per night than many people earn in a month, while just meters away, our fellow citizens are forced to make their beds on cold pavements. As a criminologist, these scenes raise critical questions about structural violence and social harms. When we discuss crime and justice in our lectures, we often talk about root causes. Here they are, laid bare on London’s streets – the direct consequences of austerity policies, inadequate mental health support, and a housing crisis that continues to push more people into precarity. But as we say in the Nigerian dictionary of life lessons – WE MOVE!! 🚀

10:31 AM Supreme Court security check time

Security check time, and LISTEN to how they’re checking our students’ water bottles! The way they’re examining those drinks is giving: Nah this looks suspicious 🤔

So there I am, breezing through security like a pro (years of academic conferences finally paying off!). Our students follow suit, all very professional and courtroom-ready. But wait for it… who’s that getting the extra-special security attention? None other than our beloved department head Manos! 😂

The security guard’s face is priceless as he looks through his bags back and forth. Jes whispers to me ‘is Manos trying to sneak in something into the supreme court?’ 😂 Maybe they mistook his collection of snacks for contraband? Or perhaps his stack of risk assessment forms looked suspicious? 😂 There he is, explaining himself, while the rest of us try (and fail) to suppress our giggles. He is a free man after all.

10: 44AM Right so first stop, – Court Room 1.

Our tour guide provided an overview of this institution, established in 2009 when it took over from the House of Lords as the UK’s highest court. The transformation from being part of the legislature to becoming a physically separate supreme court marked a crucial step in the separation of powers in the country’s legislation. There’s something powerful about standing in this room where the Justices (though they usually sit in panels of 5 or 7) make decisions. Each case mentioned had our criminology students leaning in closer, seeing how theoretical concepts from their modules materialise in this very room.

10:59 AM Moving into Court 2, the more modern one!

After exploring Courtroom 1, we moved into Court Room 2, and yep, I also saw the contrast! And apparently, our guide revealed, this is the judges’ favourite spot to dispense justice – can’t blame them, the leather chairs felt lush tbh!

Speaking of judges, give it up for our very own Joseph Buswell who absolutely nailed it when the guide asked about Supreme Court proceedings! 👏🏾 As he correctly pointed out, while we have 12 Supreme Court Justices in total, they don’t all pile in for every case. Instead, they work in panels of 3 or 5 (always keeping it odd to avoid those awkward tie situations). 👏🏾 And what makes Court Room 2 particularly significant for public access to justice the cameras and modern AV equipment which allow for those constitutional and legal debates to be broadcast to the nation. Spot that sneaky camera right at the top? Transparency level: 100% I guess!

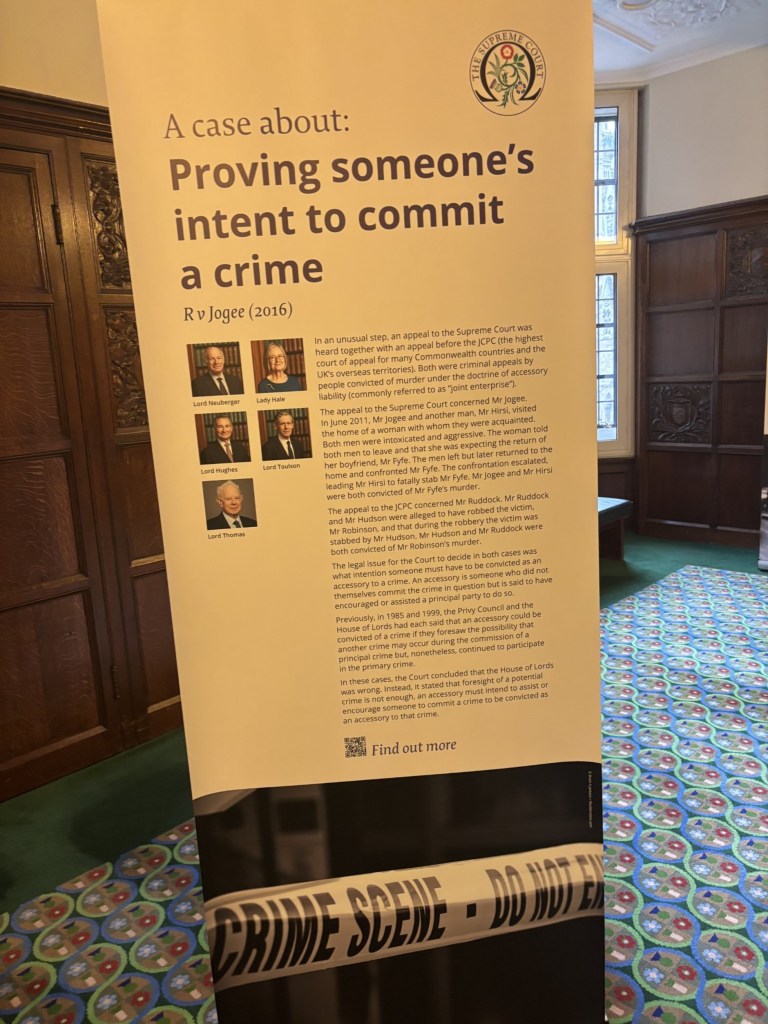

The exhibition area

The exhibition space was packed with rich historical moments from the Supreme Court’s journey. Among the displays, I found myself pausing at the wall of Justice portraits. Let’s just say it offered quite the visual commentary on our judiciary’s journey towards representation…

Beyond the portraits, the exhibition showcased crucial stories of landmark judgments that have shaped our legal landscape. Each case display reminded us how crucial diverse perspectives are in the interpretation and application of law in our multicultural society.

11: 21AM Moving into Court 3, home of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC)

The sight of those Commonwealth flags tells a powerful story about the evolution of colonial legal systems and modern voluntary jurisdiction. Our guide explained how the JCPC continues to serve as the highest court of appeal for various independent Commonwealth countries. The relationship between local courts in these jurisdictions and the JCPC raises critical questions about legal sovereignty and judicial independence and the students were particularly intrigued by how different legal systems interact within this framework – with each country maintaining its own laws and legal traditions, yet looks to London for final decisions.

Breaktime!!!!

While the group headed out in search of food, Jes and I were bringing up the rear, catching up after the holiday and literally SCREAMING about last year’s Winter Wonderland burger and hot dog prices (“£7.50 for entry too? In this Keir Starmer economy?!😱”). Anyway, half our students had scattered – some in search of sustenance, others answering the siren call of Zara (because obviously, a Supreme Court visit requires a side of retail therapy 😉).

But here’s the moment that had us STUNNED – right there on the street, who should come power-walking past but Sir Chris Whitty himself! 😱 England’s Chief Medical Officer was on a mission, absolutely zooming past us like he had an urgent SAGE meeting to get to 🏃♂️. That man moves with PURPOSE! I barely had time to nudge Jes before he’d disappeared. One second he was there, the next – gone! Clearly, those years of walking to press briefings during the pandemic have given him some serious speed-walking skills! 👀

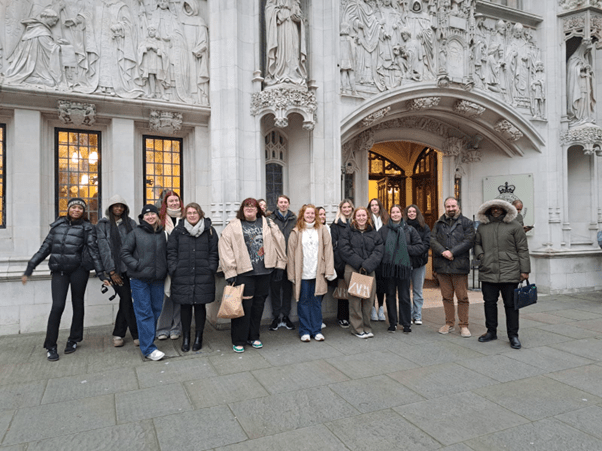

3:30 PM – Group Photo!

Looking at these final year criminology students in our group photo though! Even with that criminal early morning start (pun intended 😅), they made it through the whole Supreme Court experience! Big shout out to all of them 👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾 Can you spot me? I’m the one on the far right looking like I’m ready for Arctic exploration (as Paula mentioned yesterday), not London weather! 🥶 Listen, my ancestral thermometer was not calibrated for this kind cold today o! Had to wrap up in my hoodie like I was jollof rice in banana leaves – and you know we don’t play with our jollof! 😤

4:55 PM Heading Back To NN

On the journey back to NN, while some students dozed off (can’t blame them – legal learning is exhausting!), I found myself reflecting on everything we’d learned. From the workings of the highest court in our land to the stark realities of social inequality we witnessed near Hyde Park, today brought our theoretical classroom discussions into sharp focus. Sitting here, watching London fade into the distance, I’m reminded of why these field trips are so crucial for our students’ understanding of justice, law, and society.

Listen, can we take a moment to appreciate our driver though?! Navigating that M1 traffic like a BOSS, and getting us back safe and sound! The real MVP of the day! 👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾

And just like that, our Supreme Court trip comes to an end. From early morning rush to security check shenanigans, from spotting Chief Medical Officer on the streets to freezing our way through legal history – what a DAY!

To my amazing final years who made this trip extra special – y’all really showed why you’re the future of criminology! 👏🏾 Special shoutout to Manos (who can finally put down his attendance sheet 😂), Jes, and Liam for being the dream team! And to London… boyyyy, next time PLEASE turn up the heat! 🥶

As we all head our separate ways, some students were still chatting about the cases we learned about (while others were already dreaming about their beds 😴), In all, I can’t help but smile – because days like these? This is what university life is all about!

Until our next adventure… your frozen but fulfilled criminology lecturer, signing off! 🙌

the place is Selma

When we look at Selma through the lens of class, we are looking at a tale as old as time, Black criminality in the face of institutional violence. Black people wanting to vote and being told no. To be Black is to be criminal – savage – beast. From slavery to Selma, DuVernay’s film lays it all out for us.

Last month, as part of Freshers’ fortnight, the Students’ Union screened Ava DuVernay’s Selma – based on the true story of that three-month period in 1965, during the Civil Rights Movement before the Voting Rights Act was signed. This was a part of history when Black people were not afforded their basic human rights. Like the vote, being systematically stopped from reaching the polls. And the same sort of voting fraud still happens today.

Following Dr Martin Luther King, Jr (David Oyelowo), the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People), and this all-star cast (including Common (The Hate U Give) and Tessa Thompson (Creed) in support) we are taken on a journey showing what institutional discrimination does to communities, including the covert racism that made voting harder for a Black person than a White person – the systematic use of legal innovations to strip Black people of their rights, (and dignity).

Since Selma was released in 2014, Ava DuVernay has since made the documentary 13th showing the history behind mass incarceration in American prisons, including slavery and convict leasing. Additionally, she has made the miniseries When They See Us – looking at the story behind the Central Park Five and how the small print (in the US legal system) described in 13th was used to incarcerate these young Black and Hispanic boys.

What got to me in rewatching Selma is how important the racial thinking that (mostly) came out colonialism / slavery is in how we think about race today. The fact discrimination only became a crime in the UK in 1965 (with the Race Relations Act), and the idea we still endorsed blackface minstrelsy until the late 1970s. BBC television still had blackface as entertainment until 1978. However, slavery was outlawed in the USA in 1865 but the slave-owning class won the war on race, as Blacks continued to be treated like slaves even though they weren’t – from convict leasing to Jim Crow Laws.

One hundred years after the end of the American Civil War, like-racism (from slave days) continued. The Voting Rights Act was signed in 1965 and Jim Crow Laws were abolished as well, but those ideologies are what built America from the days of slavery, in both the North and the South. Seldom is it acknowledged that slavery existed in some northern states too.

We don’t talk about slave codes in places like Virginia, where it was stated within the law that if an altercation occurred between slave and master, and the slave died, it would not be a felony. In the slave codes for Virginia of the 1660s, it states within the laws that it was legal to kill a Black person. This was systematic use of the law to deny Black people their rights. Whether this was Virginia 1660 or Virginia 1960, not a lot had changed.

(Selma, Paramount Pictures, Pathé, and Harpo Films)

When Rosa Parkes sat down, she stood up to the establishment and unjust laws. And before Rosa Parkes, we had Collette Colvin. Moreover, when Black people boycotted the buses, they almost bankrupted the bus companies. They were seen as a nuisance. People thought they should stay in line. This old tale of Black resistance against White authority can be traced back to master, mistress, stately homes, cotton, cane and king sugar.

From the get-go, Ava DuVernay is at your throat, with her depiction of the 16th Street Baptist Church Bombing. This film was not made to score political points but it’s a film that tells it how it is, with vivid imagery of attack dogs, tear gas and police on horseback. Very much like the Klu Klux Klan killing defenseless people on the basis of race. Brutal. From Sandra Bland to Treyvon Martin, those stories of police brutality still ring true today. The history of disdain from Black communities to the police in Britain and America is one we’ve all heard, and it’s one that I think is in-part at least responsible for the lack people of colour joining up.

Why would Black, Asian and ethnic minority members of our society want to join an institution that has a historic pattern of discrimination? Why would they want to join an institution that talks about recruiting more BAME people, but still treats the ones they have already abominably?

Despite being a British viewer, there are many things I took away from this film, especially the subjectivity of the law. How White people in authority expect people of colour to be objective in the face of racism. The recent Naga Munchetty debacle with the BBC comes to mind. “You’ve got one big issue,” states LBJ (Tom Wilkinson) to King (Oyelowo). “I’ve got one hundred and one.” For most of the film, he does not appear to be taking the Black vote seriously, until it directly impacts him and what he’s trying to do.

Tim Roth as Governor Wallace (Alabama) is brilliant – spewing hate, hate and more hate with such venom. You hate him from the second his face appears on screen, and his scenes with Dylan Baker’s J. Edgar Hoover are brilliant. There is no love for Wallace. He is a White supremacist and director Ava DuVernay makes sure we know that. However, it got me asking questions about how we depict White supremacists in Britain. Mainly, with statues dotted around the country, including Parliament Square!

Is Selma a controversial film or is it simply no-nonsense and very American? It talks about things people feel uncomfortable talking about. In Britain, that includes anything remotely sounding like race, racism, colonialism or its role in Slavery. But critique Churchill or Nelson in anyway and you’re the enemy? But it does a great job recreating moments like Bloody Sunday, as state troops and local police let rip on the marchers.

“The whole nation was sickened by the pictures of that wild melee.”

Coretta Scott King (Carmen Ejogo)

From tear gas to men on horses with whips, it was riddled with symbolism, as well as truly fantastic cinematography, sound mixing and musical score. Oprah (one of the producers) was great in her role, and David Oyelowo is one of the most underrated actors working today, and a testament to an alternative image of Black men on screen. Whilst my grandparents’ generation had Harry Belafonte (Carmen Jones) and Sidney Poitier (To Sir, with Love), this current generation of Black people have David Oyelowo.

This film is rough when it needs to be but delicate when it needs to be. It’s engaging, emotional, and leaves a lump in your throat right up to and through the credits. It’s also very funny – “that White boy can hit” says Dr King after being decked by a racist local. All the speeches, all the symbols, all the nods to America’s history of slavery and oppression – it’s intertwined with how the US is today – Trump’s Twitter tantrums and all that jazz.

(Selma, Pathé, Paramount Pictures and Harpo Films)

“We must march! We must stand up! […] it is unacceptable that they use their power and keep us voiceless.”

Dr Martin Luther King, Jr (David Oyelowo)

Ava lingers on faces (especially eyes) in scenarios of extreme violence longer than what is humanly comfortable, much alike to Kathryn Bigelow with Detroit and what Steve McQueen did with Solomon Northup (Chiwetel Ejiofor) in 12 Years a Slave. From cinematography to acting, music, and sound, I have no complaints. And at moments, it was like documentary.

And nearly everyday, I’m hearing people say the system is broken; is it broken, or was it built this way, fit for purpose – for the use and upliftment of a White, male, patriarchal, able-bodied, hetero-normative society?

Bibliography

Dorsey, Bruce. “Virginian Slave Laws, 1660s”. History 41. n.p. n.d. Online. Access: 19th October, 2019.

Fryer, Peter and Gary Young et al. Staying Power: The History of Black People in Britain. London: Pluto Press, 2018. Print.

“Moral Mission.” Black and British: A Forgotten History, written by David Olusoga, directed by Naomi Austin, BBC, 2016.

Olusoga, David. Black and British: A Forgotten History. London: Pan Books, 2017. Print.

Selma. Dir. Ava DuVernay. Pathé, Paramount. 2014, Netflix.

n.d. “Slavery and the Law in Virginia”. history.org. n.p. n.d. Online. Access: 19th October, 2019.

n.d. “Slave Law in Colonial Virginia: A Timeline”. shsu.edu. n.p. n.d. Online. Access: 19th October, 2019.