Home » Women

Category Archives: Women

A reflective continuous journey

Over the last few weeks I have been in deep thought and contemplation. This has stemmed from a number of activities I have been involved in. The first of those was the Centre for the Advancement of Racial Equality (CARE) Conference, held on the 1st July. The theme this year was “Illustrating Futures – Reclaiming Race and Identity Through Creative Expressions.” It was a topic I have become both passionate and interested in over the last few years. It was really important to be part of an event that placed racial equality at the heart of its message. There were a number of speakers there, all with important messages. Assoc. Prof. Dr Sheine Peart and Dr Richard Race talked about the experiences of racialised women in higher education. They focused on the micro-aggressions they face, alongside the obstacles they encounter trying to gain promotions, or even to be taken seriously in their roles. Another key speaker during the conference was Dr Martin Glynn, unapologetically himself in his approach to teaching and his journey to getting his professor status. It was a reminder to be authentically yourself and not attempt to fit in an academic box that has been prescribed by others. As I write my first academic book, his authenticity reminded me to write my contribution to criminology in the way I see fit, with less worry and comparison to others. It was also another reminder not to doubt yourself and your abilities because of your background or your academic journey being different to others. Dr Glynn has and continues to break down barriers in and outside of the classroom and reminds us to think outside the box a little when we engage with our young students.

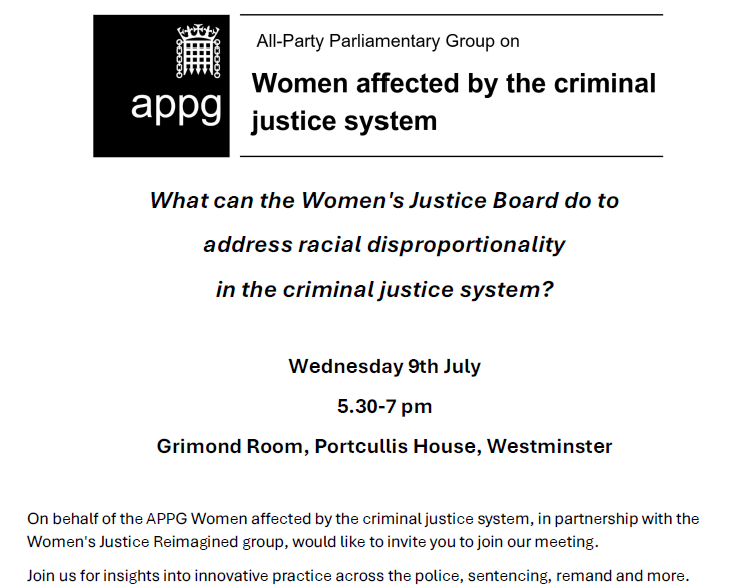

Another key event was the All-Party Parliamentary Group meeting on women in the criminal justice system. The question being addressed at the meeting was ‘What can the Women’s Justice Board do to address racial disproportionality in the criminal justice system?’. It was an opportunity for important organisations and stakeholders to stress what they believed were the key areas that needed to be addressed. Some of the charities and Non-governmental organisations were Hibiscus, Traveller Movement, The Zahid Mubarek Trust. There were also individuals from Head of Anti-slavery and Human Trafficking at HMPPS and the Deputy Mayor for Policing and Crime in London. Each representative had a unique standpoint and different calls for recommendations, ranging from:

• Hearing the voices of women affected in the CJS;

• Having culturally competent and trauma informed CJS staff;

• Ringfenced funding for specialist services and organisations like the ones that were in attendance;

• Knowing who you are serving and their needs;

• Making it a requirement to capture data on race and gender at all stages of the CJS.

It was truly great to be in a room full of individuals so ready to put the hard work in to advocate and push for change. I hope it will be one of many discussions I attend in the future.

Lastly, as I enter the final throes of writing my book on the experiences of Black women in prison I have been reflecting on what I want my book to get across, and who will be able to access it. The book represents the final outcomes of my PhD so to speak:

• To be able to disseminate the words and voices of the women that shared their stories;

• To be able to provide a visual into their lives and highlight the importance of visual research methods;

• To highlight some recommendations for change to reduce some of the pains of imprisonment faced by Black women;

• To call for more research on this group that has been rendered invisible.

Sabrina Carpenter and Feminist Utopia

I have recently been introduced to Sabrina Carpenter via online media commentary about the image of her new album cover Man’s Best Friend. Whilst some claim the image is playing with satire, the image appears to have been interpreted by others as being hyper-sexual and pandering to the male gaze.

I am not sure why this specific album cover and artist has attracted so much attention given that the hyper-sexual depiction of women is well-represented within the music industry and society more generally. However, because Sabrina’s main audience base is apparently young women under 30 it did leave me thinking about the module CRI1009 and feminist utopia, as it left me with questions that I would want to ask the students like: In a feminist utopia should the hyper-sexualized imagery of women exist?

Some might be quick to point out that this imagery should not exist as it could be seen to contribute towards the misogynistic sexualisation of women and the danger of this, as illustrated with Glasgow Women’s Aid comments about Sabrina’s album cover via Instagram (2025)

‘Sabrina Carpenter’s new album cover isn’t edgy, it’s regressive.

Picturing herself on all fours, with a man pulling her hair and calling it “Man’s Best Friend” isn’t subversion. 😐

It’s a throwback to tired tropes that reduce women to pets, props, and possessions and promote an element of violence and control. 🚩

We’ve fought too hard for this. ✊🏻

We get Sabrina’s brand is packaged up retro glam but we really don’t need to go back to the tired stereotypes of women. ✨

Sabrina is pandering to the male gaze and promoting misogynistic stereotypes, which is ironic given the majority of her fans are young women!

Come on Sabrina! You can do better! 💖’

However, thinking about utopia is always complicated as Sabrina’s brand appears to some a ‘sex-positive feminism’ by apparently allowing women to be free to represent themselves and ‘feel sexy’ rather than being controlled by the rules and expectations of other people. For some this idea of sexual freedom aka ‘sex-positive feminism’ branded via an inequitable capitalistic male dominated industry and represented by an incredibly rich white woman would be a bit of a mythical representation. As while this idea of sexy feminism is promoted by the privileged few this occurs in a societal context where many feel that women’s rights are being/at risk of being eroded and women are being subjected to sexual violence on a daily basis.

I am not sure what a workshop discussion with CRI1009 students would conclude about this, but certainly there would need to be a circling back to more never- ending foundational questions about utopia: what else would exist in this feminist utopia? Whose feminist utopic vision should get priority? Would anyone be damaged in a utopic society that does promote this hyper-sexualization? If so, should this utopia prioritise individual expression or have collective responsibility? In a society without hyper-sexualisation of women would there be rule breakers, and if so, what do you do with them?

Black History Month 2024

We have entered Black History Month (BHM), and whilst to some it is clear that Black history isn’t and shouldn’t be confined to one month a year, it would be unwise not to take advantage of this month to educate, raise awareness and celebrate Blackness, Black culture.

This year the Criminology department is planning a few events designed to be fun, informative and interesting.

One event the department will hold is a BHM quiz, designed to be fun and test your knowledge. Work individually or in groups, the choice is yours. The quiz will be held on the 17th October in The Hide (4th floor) in the Learning Hub from 4.30-6pm.

The second event will draw on the theme of this year’s BHM which is all about reclaiming narratives. In the exhibition area (ground floor of the Learning Hub) we will be presenting a number of visual narratives. I will be displaying a series of identity trees from Black women that I interviewed as part of my PhD research on Black women in English prisons. With a focus on race and gender, these identity trees represent a snapshot of the lives and lived experiences of these women prior to imprisonment. The trees also highlight the hopes and resilience of these women. This event will be held on the 31st October between 4.30-6pm. Please do walk through and have a look at the trees and ask questions. The event is designed for you to spend as little or as much time as you would like, whether it is a brief look or a longer discussion your presence is much welcomed!

If you would like to be part of this event, whether that is sharing your own research (staff and students), or if you would like to use the space to share your own narrative as a Black individual please get in contact by the 21st October by emailing angela.charles@northampton.ac.uk or criminology@northampton.ac.uk

Lastly, I would like to put a spotlight on a few academics to maybe read up on this month and beyond:

A few suggestions for important discussions on Black feminism and intersectionality:

A few academics with powerful and interesting research that proved very important in my PhD research:

Victims of Domestic Violence Repeatedly Failed by UK Police Forces

On the last day of August 2024 I was invited to an event focused on “Victims of Domestic Violence Repeatedly Failed by UK Police Forces” held at Fenny Compton Village Hall. The choice of venue was deliberate, it was the same venue where Alan Bates brought together for the first time, just some of the many post-masters/mistresses impacted by, what we now recognise as, Britain’s largest miscarriage of justice. This meeting demonstrated that rather than one or two isolated incidents, this was widespread impacting 100s of people. Additionally, the bringing of people together led to the creation of the Justice for Sub-Postmasters Alliance [JFSA], a collective able to campaign more effectively, showing clearly that there is both strength and purpose in numbers.

Thus the choice of venue implicitly encouraged attendees to take strength in collectivity. Organised by three women who had lost daughters and a niece who instinctively knew that they weren’t the only ones. Furthermore, each had faced barrier after barrier when trying to find out what had happened to their loved ones leading up to and during their deaths. What they experienced individually in different areas of the country, shared far more commonality than difference. By comparing their experiences, it became clear that their losses were not unique, that across the country and indeed, the world, women were being subjected to violence, dying, grieving and being subjected to organisational indifference, apathy, if not downright institutional violence.

At the event, woman after woman, spoke of different women, very much loved, some had died, some had fled their violent partners (permanently, one hopes) and others who were still trapped in a living hell. Some spoke with confidence, others with trepidation or nerves, all filled with anguish, passion and each determined to raise their voices. Again and again they detailed their heartbreaking testimony, which again showed far more commonality than difference:

- Women being told that their reporting of domestic abuse incidents may make things much worse for them

- Evidence lost or disposed of by police officers

- Corrupted or deleted body worn camera footage

- Inability or unwillingness to recognise that domestic abuse, particularly coercive behaviour escalates, these are not separate incidents and cannot be viewed in isolation

- Police often dismissing women’s reports as examples of “minor” or “borderline” domestic abuse, when as detailed above, individual incidents in isolation do not reflect the lived experience

- History of domestic abuse ignored/disregarded whether or not recorded by the police

- Victims of domestic abuse being asked for forensic levels of detail when trying to report

- Victims of domestic abuse being incorrectly refused access by the police to access to information covered by Clare’s Law (Domestic Violence Disclosure Scheme)

- The Domestic Abuse, Stalking and Honour Based Violence [DASH} forms treated as tick box exercise, often done over harried phone calls

- Victims of domestic violence, criminalised when trying to protect themselves and their children from violent partners

- When escaping from violent relationships women are placed in refuges, often far from their support networks, children move schools losing their friendship circles and breaking trusted relationships with teachers

- Suicide not investigated according to College of Policing own guidance: Assume Nothing, Believe nobody, Challenge everything!

- Police failing to inform the parents of women who have died

- Dead women’s phones and laptops handed over to the men who have subjected them to violence (under the guise of next-of-kin)

- The police overreliance on testimony of men (who have subjected them to violence previously) in relation to their deaths

- Challenges in accessing Legal Aid, particularly when the woman and children remain in the family home

- The lack of joined up support, lots of people and charities trying to help on limited resources but reacting on an ad hoc basis

- The police would rather use valuable resources to fight victims, survivors and their families’ complaints against them

The above is by no means an exhaustive list, but these issues came up again and again, showing clearly, that none of the women’s experiences are unique but are instead repeated again and again over time and place. It doesn’t matter what year, what police force, what area the victim lived in, their education, their profession, their class, marital status, or whether or not they were mothers. It is evident from the day’s testimony that women are being failed not only by the police, but also the wider Criminal Justice System.

Whilst the women have been failed, the criminologist in me, says we should consider whether the police are actually “failing” or whether they are simply doing what they were set up to do, and women are simply collateral damage. Don’t forget the police as an institution are not yet 200 years. They were set up to protect the rich and powerful and maintain control of the streets. Historically, we have seen the police used against the population, for example policing the Miners’ Strikes, particularly at Orgreave. More recently the response to those involved in violent protest/riots demonstrates explicitly that the police and the criminal justice system can act swiftly, when it suits. But consider what it is trying to protect, individuals or businesses or institutions or the State?

The police have long been faced by accusations of institutional racism, homophobia and misogyny. It predominantly remains a institution comprised of white, straight, (nominally) Christian, working class, men, despite frequent promises to encourage those who do not fit into these five classifications to enlist in the force. Until the police (and the wider CJS) are prepared to create a less hostile environment, any attempt at diversifying the workforce will fail. If it continues with its current policies and practices without input from those subjected to them, both inside and outside the institution, any attempt at diversifying the institution will fail. But again we come back to that word ‘failure’, is it failing if the institution continues to maintain the status quo, to protect the rich and powerful and maintain control of the streets?

But does the problem lie solely with the police and the wider criminal justice system, or are we continually failing as a society to support, nurture and protect women? Take for example Hearn’s astute recognition that ‘[f]or much too long men have been considered the taken-for-granted norm against which women have been judged to be different’ offers an alternative rationale (1998: 3).Many scholars have explored language in relation to women and race, identifying that in many cases the default is understood to be a white male (cf. de Beauvoir, 1949/2010, Lakoff, 1973, Spender, 1980, Eichler, 1988/1991, Penelope, 1990, Homans, 1997). As de Beauvoir evocatively writes, ‘humanity is male and man defines woman not in herself, she is not regarded as an autonomous being […] He is the Subject; he is the Absolute. She is the Other’ (de Beauvoir, 1949/2010: 26). Lakoff (1973) also notes that the way in which language is used both about them and by them, disguises and enables marginalisation and disempowerment. Furthermore, it enables the erasure of women’s experience. The image below illustrates this well, with its headline figure relating to men. Whilst not meaning to dismiss any violence, when women’s victimisation far outweighs that faced by men, this makes no logical sense.

Nevertheless, we should not forget men as Whitehead dolefully concludes:

‘to recognize the extent and range of men’s violences is to face the depressing and disturbing realization that men’s propensity for cruelty and violence is probably the biggest cause of misery in the world (2002: 36).’

Certainly numerous authors have identified the centrality of men (and by default masculinity) to any discussion of violence. These range from Hearn’s powerful assertion that it is ‘men [who] dominate the business of violence, and who specialize in violence’ (1998: 36) to Mullins (2006) suggestion that women act as both stimulation for men’s violence (e.g. protection) and as a limiter. Certainly, Solnit perceptively argues that armed with the knowledge that men are responsible for far more violence, it should be possible to ‘theorise where violence comes from and what we can do about it a lot more profoundly’ (2014: 25).

All of the challenges and barriers identified on the day and above make it incredibly difficult, even for educated well-connected women to deal with, this is compounded when English is not your first language, or you have a visa dependant on your violent partner/husband, or hold refugee status. As various speakers, including the spokeswoman for Sikh Women’s Aid made clear, heritage and culture can add further layers of complexity when it comes to domestic abuse.

Ultimately, the event showed the resilience and determination of those involved. It identified some of the main challenges, paid tribute to both victims and survivors and opened a new space for dialogue and collective action. If you would like to keep up with their campaign, they use the hashtag #policefailingsuk and can be contacted via email: policefailings.uk@yahoo.com

References

de Beauvoir, Simone, (1949/2010), The Second Sex, tr. from the French by Constance Borde and Sheila Malovany Chevalier, (New York: Vintage Books)

Eicler, Margrit, (1988/1991), Nonsexist Research Methods, (London: Routledge) (Kindle Version)

Hearn, Jeff, (1998), The Violences of Men, (London, Sage Publications Ltd)

Homans, Margaret, (1997), ‘“Racial Composition”: Metaphor and the Body in the Writing of Race’ in Elizabeth Abel, Barbara Christian and Helene Moglen, (Eds), Female Subjects in Black and White, (London: University of California Press): 77-101

Lakoff, Robin, (1973), ‘Language and Woman’s Place,’ Language in Society, 2, 1: 45-80

Mullins, Christopher W., (2006), Holding Your Square: Masculinities, Streetlife and Violence, (Cullompton: Willan Publishing)

National Centre for Domestic Violence, (2023), ‘Domestic Abuse Statistics UK,’ National Centre for Domestic Violence, [online]. Available from: https://www.ncdv.org.uk/domestic-abuse-statistics-uk/ [Last accessed 31 August 2024]

Penelope, Julia, (1990), Speaking Freely: Unlearning the Lies of the Fathers’ Tongues, (New York: Pergamon Press)

Solnit, Rebecca, (2014), Men Explain Things to Me, (London: Granta Publications)

Spender, Dale, (1980), Man Made Language, (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul)

Whitehead, Stephen M., (2002), Men and Masculinities, (Cambridge: Polity Press)

The Problem with True Crime

There has been a huge spike in interest in true crime in recent years. The introduction to some of the most notorious crimes have been presented on Netflix and other streaming platforms, that has further reinforced the human interest in the gore of violent crimes.

Recently I went to the theatre to watch a show title the Serial Killer Next Door, which highlights some of the most notorious crimes to sweep the nation. From the Toy Box Killer (David Ray-Parker) and his most brutal violence against women to Ed Kemper and the continuous failing by the FBI to bring one of the most violent and prolific killers to justice. While I was horrified by the description both verbal and photographic of the crimes committed, by the serial killers. I was even more shocked at the reaction of the audience and how the cases were presented. The show attempted to sympathise with the victims but this fell short as the entertainment value of the audience was paramount and thus, the presenter honed in on the ‘comedic’ factor of the criminal and the crimes committed. Graphic pictures of the naked bodies of men, women and children brutalised at the hands of the most sadistic monsters were put on screens for speculation and entertainment. Audience members enjoyed popcorn and crisps while lapping up the horror displayed.

I did not stay for the full show…..

The level of distaste was too much for me but from what I did watch made me reflect deeply and led me to the age-old topic among criminologists and victimologists that question where the victims are and why do they continue to be dehumanised. Victims of these heinous crimes are rarely remembered and depicted in a way that moves them away from being viewed as human and instead commodities and after thoughts of crime.

The true crime community on YouTube has been criticized for the sensationalist approach crime. With niche story telling while applying one’s makeup and relaying the most brutal aspects of true crime cases to audiences. I ask the question when and how did we get to this point in society where entertainment trumps victims and their families. Later, this year I will be bringing this topic to a true crime panel to further explore the damage that this type of entertainment has on both the consumer and the victim’s legacy. The dehumanisation of victims and desensitisation of consumers for entertainment tells us something about the society we live in that should be addressed…..I am sure there will be other parts to this post that will explore the issues with true crime and its problematic and exploitative nature.

Witches, Broomsticks and Libraries

My son has been gifted and collected many delightful children’s books since his recent birth. A book which stands out to me on Women’s History Month is: Room on the Broom (2001) by writer Julia Donaldson and Illustrator Axel Scheffler.

Aside from the fabulous use of words and illustrations, the main character of the story is a lovely witch who makes room on her broom for her cat, a dog, bird and frog. The latter part of the story consists of the broom snapping, presumably due to the extra weight of these passengers, then the witch risks being eaten by a dragon. But eventually all is well as the witch creates a new super broomstick with;

seats for the witch

and the cat and the dog,

a nest for the bird and

a shower for the frog.

This book’s depiction of the witch as a morally good character is wonderful but this is not usual. In popular culture, such as fiction, television and film witches seem to have flawed character traits, are morally bad cackling devious women who fly about casting spells on poor and (un/)suspecting folk.

The negative connotations of witches today reflect a long dreadful real-life history of outsiders being accused of being witches – with some being tortured and murdered due to this. The outsiders aka witches tended to be women, women who were providing a service for other women, such as support during childbirth or healing practices, or those that practice spiritualisms that differ to dominant religions. If re-born today some of these women may have been celebrated as midwifes and nurses, although their wages and workloads would still illustrate that predominantly women centered roles tend to be under appreciated.

On International Women’s Day I finished reading Disobedient Bodies (2023) by Emma Dabiri. Disobedient Bodies reminds me about how in a white capitalist cis male world bodies categorised as female and women are constructed as deviant. Proof of being a witch was apparently not just found in practices but on the bodies of women. Emma Dabiri adds to the discussion on witches that I did not consider; that groups of women aka groups of deviant witches were considered to be the most threatening to witch hunters. For a long time women have been pitted against each other, the historical nature of women meeting in groups to support each other as a threat to patriarchal capitalist white systems has added to this.

My son is very privileged to have so many book at the age of 1. Unfortunately I am writing during a time where there are threats to close 25 libraries in Birmingham. Notably, the libraries that me and my son frequent consist of mostly women staff (both paid and volunteers). In addition to the potential for job losses, if this happens there will be babies, children and adults without access to books, artistic classes, warm and safe spaces. To quote my friend and colleague, “soon there will be nothing left”.

Doing the right thing

It seems that very often, the problem with politics in this country is that it gets in the way of doing the right thing. Despite the introduction of the The Seven Principles of Public Life known as the Nolan Principles, politicians (not all of them of course, but you will have seen ample examples) still seem to be hell bent on scoring political advantage, obfuscating on matters of principle and where possible avoiding real leadership when the country is crying out for it. Instead, they look to find someone, anyone, else to blame for failures that can only be described as laying clearly at the door of government and at times the wider institution of parliament.

One example you may recall was the complete farce in parliament where the speaker, Sir Lyndsay Hoyle, was berated for political interference and breaking the rules of the house prior to a debate about a ceasefire in Gaza. It became quite obvious to anyone on the outside that various political parties, Conservatives, Labour and the Scottish National Party were all in it to score points. The upshot, rather than the headlines being about a demand for a ceasefire in Gaza, the headlines were about political nonsense, even suggesting that the very core of our democracy was at stake. Somehow, they all lost sight of what was important, the crises, and it really is still a crisis, in Gaza. Doing the right thing was clearly not on their minds, morals and principles were lost along the way in the thrust for the best political posturing.

And then we come to the latest saga involving political parties, the WASPI women (Women Against State Pension Inequality) campaign. The report from the Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman has ruled that the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) “failed to provide accurate, adequate and timely information” about changes to pension ages for women. The report makes interesting reading. In essence, it accuses the DWP of maladministration on several counts.

The Pensions Act 1995 changed the way in which women could draw their pensions in an effort to equalise the age with men. A timetable was drawn up raising the qualifying age for women from 60 to 65, with the change phased in between 2010 and 2020. However, under the Pensions Act 2011, the new qualifying age of 65 for women was brought forward to 2018. The report acknowledges that the DWP carried out campaigns from 1995 onwards but in 2004 received results of research that a considerable number of affected women still believed that their retiring age was 60. Unfortunately, through prevarication and for some quite inexplicable reasoning the women affected were not notified or were notified far too late. There was a calculation carried out that suggested some women were not told until 18 months before their intended retirement date. The matter was taken before the courts but the courts ruling did nothing to resolve the issue other than providing a ruling that the DWP were not required by law to notify the women.

You can read about the debacle anywhere on the Internet and the WASPI women have their own Facebook page. What seems astounding is that both the Government and the opposition have steadfastly avoided being drawn on the matter of compensation for these women. I should add that the maladministration has had serious detrimental impacts on many of them. Not even a sorry, we got it wrong. Instead we see articles written by right wing Conservatives suggesting the women had been provided with ample warning. If you read the report, it makes it clear that provisions under the Civil Service Code were not complied with. It is maladministration and it took place under a number of different governments.

Not getting it right in the first instance was compounded by not getting it right several times over later on. It seems that given the likely cost to the taxpayer, this maladministration is likely, like so many other cock ups by government and its agencies, to be kicked into the long grass. Doing the right thing is a very long, long way away in British politics. And lets not forget the Post Office scandal, the infected blood transfusion scandal and the Windrush scandal to name but a few. So little accountability, such cost to those impacted.

- The quotation in the image is often wrongly misattributed to C. S. Lewis. ↩︎