Home » War (Page 2)

Category Archives: War

Let us not forget

Yesterday marked the 80th anniversary of the D Day landings and it has seen significant coverage from the media as veterans, families, dignitaries, and others converge on the beaches and nearby towns in France. If you have watched the news coverage during the week, you will have seen interviews with the veterans involved in those landings. What struck me about those interviews was the humbleness of those involved, they don’t consider themselves heroes but reserve that word for those that died. For most of us, war is something that happens elsewhere, and we can only glimpse the horrors of war in our imaginations. For some though, it is only too real, and for some, it is a reality now.

I was struck by some of the conversations. Imagine being on ship, sailing across the English Channel and looking back at the white cliffs of Dover and being told by someone in charge, ‘have a good look because a lot of you will never see them again’. If knowing that you are going to war was not bad enough, that was a stark reminder that war means a high chance of death. And most of those men going over to France were young, to put it in perspective, the age of our university students. If you watched the news, you will have seen the war cemeteries with rows upon rows, upon rows of headstones, each a grave of someone whose life was cut short. Of course, that only represents a small number of the combatants that died in the war, there are too many graveyards to mention, too many people that died. Too many people both military and civilian that suffered.

The commemoration of the D Day landings and many other such commemorations serve as a reminder of the horrors of war when we have the opportunity to hear the stories of those involved. But as their numbers dwindle, so too does the narrative of the reality, only to be replaced with some romantic notion about glory and death. There is no glory in war, only death, suffering and destruction.

The repeated, ‘never again’ after the first and second world war seems to have been a utopian dream. Whilst we may have been spared the horrors of a world war to this point, we should not forget the conflicts across the world, too numerous to list here. Often, the reasons behind them are difficult to comprehend given the inevitable outcomes. As one veteran on the news pointed out though ‘war is a nonsense, but sometimes it’s necessary’.

The second part of that is a difficult sentiment to swallow but then, if your country faces invasion, your people face being driven from their homes or into slavery or worse, then choices become very stark. We should be grateful to those people that fought for our freedoms that we enjoy now. We should remember that there are people doing the same across the world for their own freedoms and perhaps vicariously ours. And perhaps, we should look to ourselves and think about our tolerance for others. Let us not forget, war is a nonsense, and there is no glory in it, only death and destruction.

Liberalism, Capitalism and Broken Promises

With international conflict rife, imperialism alive and well and global and domestic inequalities broadening, where are the benefits that the international liberal order promised?

As part of my masters, I am reading through an interesting textbook named Theories of International Relations (Burchill, 2013). Soon, I’ll have a lecture speaking about liberalism within the realm of international relations (IR). The textbook mentions liberal thought concerning the achievement of peace through processes of democracy and free trade, supposedly, through these mechanisms, humankind can reach a place of ‘perpetual peace’, as suggested by Kant.

Capitalism supposedly has the power to distribute scarce resources to citizens, while liberalist free trade should break down artificial barriers between nations, uniting them towards a common goal of sharing commodities and mitigating tensions by bringing states into the free trade ‘community’. With this, in theory, should bring universal and democratic peace, bought about by the presence of shared interest.

Liberal capitalism has had a long time to prove its worth, with the ideology being adopted by the majority of the west, and often imposed on countries in the global south through coercive trade deals, political interference and the establishment of dependant economies. Evidence of the positives of liberal capitalism, in my opinion are yet to be seen. In fact, the evidence points towards a global and local environment entirely contrary to the claims of liberal capitalism.

The international institutions, constructed to mitigate against the anarchic system we live under become increasingly fragile and powerless. The guarantee of global community and peace seems further and further away. The pledge that liberalism will result in the spread of resources, resulting in the ultimate equalisation is unrealised.

Despite all of this, the global liberal order seems to still be supported by the majority of the elite and by voters alike. Because with the outlined claims comes the promise that one day, with some persistence, patience and hard work, you too could reap the rewards of capitalism just like the few in society do.

Civilian Suffering Beyond the Headlines

In the cacophony of war, amidst the geopolitical chess moves and strategic considerations, it’s all too easy to lose sight of the human faces caught in its relentless grip. The civilians, the innocents, the ordinary people whose lives are shattered by the violence they never asked for. Yet, as history often reminds us, their stories are the ones that linger long after the guns fall silent. In this exploration, we delve into the forgotten narratives of civilian suffering, from the tragic events of Bloody Sunday to the plight of refugees and aid workers in conflict zones like Palestine.

On January 30, 1972, the world watched in horror as British soldiers opened fire on unarmed civil rights demonstrators in Northern Ireland, in what would become known as Bloody Sunday. Fourteen innocent civilians lost their lives that day, and many more were injured physically and emotionally. Yet, as the decades passed, the memory of Bloody Sunday faded from public consciousness, overshadowed by other conflicts and crises. But for those who lost loved ones, the pain and trauma endure, a reminder of the human cost of political turmoil and sectarian strife.

Fast forward to the present day, and we find a world still grappling with the consequences of war and displacement. In the Middle East, millions of Palestinians endure the daily hardships of life under occupation, their voices drowned out by the rhetoric of politicians and the roar of military jets. Yet amid the rubble and despair, there are those who refuse to be silenced, who risk their lives to provide aid and assistance to those in need. These unsung heroes, whether they be doctors treating the wounded or volunteers distributing food and supplies, embody the spirit of solidarity and compassion that transcends borders and boundaries.

But even as we celebrate their courage and resilience, we must also confront our own complicity in perpetuating the cycles of violence and injustice that afflict so many around the world. For every bomb that falls and every bullet that is fired, there are countless civilians who pay the price, their lives forever altered by forces beyond their control. And yet, all too often, their suffering is relegated to the footnotes of history, overshadowed by the grand narratives of power and politics.

So how do we break free from this cycle of forgetting? How do we ensure that the voices of the marginalized and the oppressed are heard, even in the midst of chaos and conflict? Perhaps the answer lies in bearing witness, in refusing to turn away from the harsh realities of war and its aftermath. It requires us to listen to the stories of those who have been silenced, to amplify their voices and demand justice on their behalf.

Moreover, it necessitates a revaluation of our own priorities and prejudices, a recognition that the struggle for peace and justice is not confined to distant shores but is woven into the fabric of our own communities. Whether it’s challenging the narratives of militarism and nationalism or supporting grassroots movements for social change, each of us has a role to play in building a more just and compassionate world.

The forgotten faces of war remind us of the urgent need to confront our collective amnesia and remember the human cost of conflict. From the victims of Bloody Sunday to the refugees fleeing violence and persecution, their stories demand to be heard and their suffering acknowledged. Only then can we hope to break free from the cycle of violence and build a future were peace and justice reigns supreme.

Feminism, Security and Conflict

Content warning: this blog post mentions feminist theory in relation to issues of rape, genocide and war.

Recently I had the opportunity to do a deep dive into feminist contributions to the field of international relations, a discipline which of course has many parallels and connections to criminology. Feminism as a broad concept often is viewed from a human rights perspective, which makes sense as this is probably the area that is most visible to most people through progressions in the field of political participation, reproductive and sexual rights and working rights. A lesser known contribution is feminist theory to international relations (IR), specifically, its practical and theoretical contribution to security and conflict. This blog post will give a whistle stop tour through the exploration I conducted concerning the themes of security, conflict and feminism. Hopefully I can write this in a way everyone finds interesting as it’s a fairly heavy topic at times!

Security

Within IR, security has usually been defined on a more state-centric level. If a state can defend itself and its sovereign borders and has adequate (or more than adequate) military power, it is seen to be in a condition of security according to realist theory (think Hobbes and Machiavelli). Realism has taken centre stage in IR, suggesting that the state is the most important unit of analysis therefore meaning security has generally taken a state-centric definition.

Feminism has offered a radical rejuvenation of not only security studies, but also the ontological principles of IR itself. While the state is preoccupied with providing military security, often pooling resources towards this sector during times of international fragility, welfare sectors are usually plunged into a state of underfunding- even more so than they usually are. This means that individuals who depend on such sectors are often left in a state of financial and/or social insecurity. Feminism focuses on this issue, suggesting women are often the recipients of various welfare based services. The impact of wartime fiscal policy would not have been uncovered without feminism paying attention to the women typically side-lined and ignored in international politics. So while the state is experiencing a sense of security, its citizens (quite often women) are in a feeling of insecurity.

This individualisation of security also challenges the merit of using such a narrow, state-centric definition of security, ultimately questioning the validity of the dominant, state-focused theory of realism which in IR, is pretty ground-breaking.

Conflict

I’d say that in nearly all social science disciplines, including politics, economics, sociology, IR and criminology, conflict and war is something that is conceptualised as inherently ‘masculine’. Feminist theory was one of the first schools to document this and problematise it through scholarship which interrogated hegemonic masculinity, ‘masculine’ institutions and the manifestations of these things in war zones.

Wartime/ genocidal rape is unfortunately not a rare behaviour to come across in the global arena. The aftermath of the Yugoslav wars and the Rwandan genocide is probably some of the most reported cases in academic literature, and this is thanks to feminist theory shining a light on the phenomena. Feminism articulates wartime/ genocidal rape as constitutive of the dangerous aspects of culturally imbedded conceptions of masculinity being underscored by power and domination and being legitimised by the institutions which champion dangerous elements of masculinity.

Practically, this new perspective provided by feminism has altered the way sexual violence is viewed by the mainstream; once a firmly domestic problem, sexual violence has been brought into foreign policy and recognised as a tactic of war. This articulation by feminist theory is absolutely ground breaking in the social science world as it shifts the onto-epistemological focus that other more conventional schools have been unable to look past.

Christmas Toys

In CRI3002 we reflected on the toxic masculine practices which are enacted in everyday life. Hegemonic masculinity promotes the ideology that the most respectable way of being ‘a man’ is to engage in masculine practices that maintain the White elite’s domination of marginalised people and nations. What is interesting is that in a world that continues to be incredibly violent, the toxicity of state-inflicted hegemonic masculinity is rarely mentioned.

The militaristic use of State violence in the form of the brutal destruction of people in the name of apparent ‘just’ conflicts is incredibly masculine. To illustrate, when it is perceived and constructed that a privileged position and nation is under threat, hegemonic masculinity would ensure that violent measures are used to combat this threat.

For some, life is so precious yet for others, life is so easily taken away. Whilst some have engaged in Christmas traditions of spending time with the family, opening presents and eating luxurious foods, some are experiencing horrors that should only ever be read in a dystopian novel.

Through privileged Christmas play-time with new toys like soldiers and weapons, masculine violence continues to be normalised. Whilst for some children, soldiers and weapons have caused them to be victims of wars with the most catastrophic consequences.

Even through children’s play-time the privileged have managed to promote everyday militarism for their own interests of power, money and domination. Those in the Global North are lead to believe that we should be proud of the army and how it protects ‘us’ by dominating ‘them’ (i.e., ‘others/lesser humans and nations’).

Still in 2023 children play with symbolically violent toys whilst not being socialised to question this. The militaristic toys are marketed to be fun and exciting – perhaps promoting apathy rather than empathy. If promoting apathy, how will the world ever change? Surely the privileged should be raising their children to be ashamed of the use of violence rather than be proud of it?

Festive messages, a legendary truce, and some massacres: A Xmas story

Holidays come with context! They bring messages of stories that transcend tight religious or national confines. This is why despite Christmas being a Christian celebration it has universal messages about peace on earth, hope and love to all. Similar messages are shared at different celebrations from other religions which contain similar ecumenical meanings.

The first official Christmas took place on 336 AD when the first Christian Emperor declared an official celebration. At first, a rather small occasion but it soon became the festival of the winter which spread across the Roman empire. All through the centuries more and more customs were added to the celebration and as Europeans “carried” the holiday to other continents it became increasingly an international celebration. Of course, joy and happiness weren’t the only things that brought people together. As this is a Christmas message from a criminological perspective don’t expect it to be too cuddly!

As early as 390 AD, Christmas in Milan was marked with the act of public “repentance” from Emperor Theodosius, after the massacre of Thessalonica. When the emperor got mad they slaughtered the local population, in an act that caused even the repulson of Ambrose, Bishop of Milan to ban him from church until he repented! Considering the volume of people murdered this probably counts as one of those lighter sentences; but for people in power sentences tend to be light regardless of the historical context.

One of those Christmas celebrations that stand out through time, as a symbol of truce, was the 1914 Christmas in the midst of the Great War. The story of how the opposing troops exchanged Christmas messages, songs in some part of the trenches resonated, but has never been repeated. Ironically neither of the High Commands of the opposing sides liked the idea. Perhaps they became concerned that it would become more difficult to kill someone that you have humanised hours before. For example, a similar truce was not observed in World War 2 and in subsequent conflicts, High Commands tend to limit operations on the day, providing some additional access to messages from home, some light entertainment some festive meals, to remind people that there is life beyond war.

A different kind of Christmas was celebrated in Italy in the mid-80s. The Christmas massacre of 1984 Strage Di Natale dominated the news. It was a terrorist attack by the mafia against the judiciary who had tried to purge the organisation. Their response was brutal and a clear indication that they remained defiant. It will take decades before the organisation’s influence diminishes but, on that date, with the death of people they also achieved worldwide condemnation.

A decade later in the 90s there was the Christmas massacre or Masacre de Navidad in Bolivia. On this occasion the government troops decided to murder miners in a rural community, as the mine was sold off to foreign investors, who needed their investment protected. The community continue to carry the marks of these events, whilst the investors simply sold and moved on to their next profitable venture.

In 2008 there was the Christmas massacre in the Democratic Republic of Congo when the Lord’s Resistance Army entered Haut-Uele District. The exact number of those murdered remains unknown and it adds misery to this already beleaguered country with such a long history of suffering, including colonial ethnic cleansing and genocide. This country, like many countries in the world, are relegated into the small columns on the news and are mostly neglected by the international community.

So, why on a festive day that commemorates love, peace and goodwill does one talk about death and destruction? It is because of all those heartfelt notions that we need to look at what really happens. What is the point of saying peace on earth, when Gaza is levelled to the ground? Why offer season’s wishes when troops on either side of the Dnipro River are still fighting a war with no end? How hypocritical is it to say Merry Christmas to those who flee Nagorno Karabakh? What is the point of talking about love when children living in Yemen may never get to feel it? Why go to the trouble of setting up a festive dinner when people in Ethiopia experience famine yet again?

We say words that commemorate a festive season, but do we really mean them? If we did, a call for international truce, protection of the non-combatants, medical attention to the injured and the infirm should be the top priority. The advancement of civilization is not measured by smart phones, talking doorbells and clever televisions. It is measured by the ability of the international community to take a stand and rehabilitate humanity, thus putting people over profit. Sending a message for peace not as a wish but as an urgent action is our outmost priority.

The Criminology Team, wishes all of you personal and international peace!

What value life in a far-off land?

Watching the BBC news and for that matter any other news broadcast has become almost unbearable. Over the last three weeks or so the television screen has been filled with images of violence, grief, and suffering. Images of innocent men, women and children killed or maimed or kidnapped. Images of grieving relatives, images of people with little or no hope. And as I watch I am consumed by overwhelming sadness and as I write this blog, I cannot avoid the tears welling up. And I am angry, angry at those that could perpetuate such crimes against humanity. I will not take sides as I know that I understand so little about the conflict in Israel, Gaza, and the surrounding area, but I do feel the need to comment. It seems to me that there is shared blame across the countries involved, the region, and the rest of the world.

As I watch the news, I see reports of protest across many countries, and I see a worrying development of Islamophobia and Antisemitism. The conflict is only adding fuel to the actions of those driven by hatred and it provides plenty of scope for politicians in the West and other countries, to pontificate, and partake in political wrangling and manoeuvring before showing their abject disregard for morality and humanity. The fact that Hamas, as we are constantly reminded by the BBC, is a proscribed terrorist organisation, proscribed by most countries in the west, including the United Kingdom, seems to give carte blanche to western politicians to support crimes against humanity, to support murder and terrorism. How else can we describe what is going on?

The actions of Hamas should and quite rightly are to be condemned, any action that sees the killing of innocent lives is wrong. To have carried out their recent attacks in Israel in such a manner was horrendous and is a reminder of the dangers that the Israeli people face daily. But the declaration by Israel that it wants to remove Hamas from the face of the earth would, and could, only lead to one outcome, that being played out before our very eyes. The approach seems to be one of vengeance, regardless of the human cost and regardless of any rules of war or conflict or human dignity. How else can the bombing and shelling of a whole country be explained? How else can the blockading of a country to bring it to the brink of disaster be justified? How do we explain the forced migration of innocent people from one part of a country to another only to find that the edict to move led them into as dangerous a place as that they moved from? There seems to be a very sad irony in this, given the historical perspectives of the Israeli nation and its people.

We don’t know what efforts are going on behind the scenes to attempt to bring about peace but the outrageous comments and actions or omissions by some western politicians beggar belief. From Joe Biden’s declaration ‘now is not the time for a ceasefire’ to our government’s and the opposition’s policy that a pause in the conflict should occur, but not a ceasefire, only demonstrates a complete lack of empathy for the plight of Palestinian people. If not now, at what time would it be appropriate for a ceasefire to occur? It seems to me, as a colleague suggested, politicians and many others seem to be more concerned about accusations of antisemitism than they are about humanity. Operating in a moral vacuum seems to be par for the government in the UK and unfortunately that seems to extend to the other side of the house. Just as condemning the killing of innocent people is not Antisemitic nor too are the protests about those killings a hate crime. Our home secretary seems to have nailed her colours to the mast on that one but I’m not sure if its xenophobia, power lust or something else being displayed. Populism and a looming general election seems to be far more important than innocent children’s lives in a far off land.

The following quote seems so apt:

‘…. politicians must shoulder their share of the blame. And individuals too. Those ordinary citizens who allowed themselves to be incited into hatred and religious xenophobia, who set aside decades, sometimes centuries of friendship, who took up sword and flame to terrorise their neighbours and compatriots, to murder men, women, and children in a frenzy of bloodlust that even now is difficult to comprehend (Khan, 2021: 323).’[1]

If you are not angry, you should be, if you do not cry, then I ask why not? This is not the way that humanity should behave, this is humanity at its worst. Just because it is somewhere else, because it involves people of a different race, colour or creed doesn’t make it any less horrendous.

Khan, V. (2021) Midnight at Malabar House, Hodder and Stoughton: London.

[1] Vaseem Khan was discussing Partition on the Indian subcontinent, but it doesn’t seem to matter where the conflict is or what goes on, the reasons for it are so hard to comprehend.

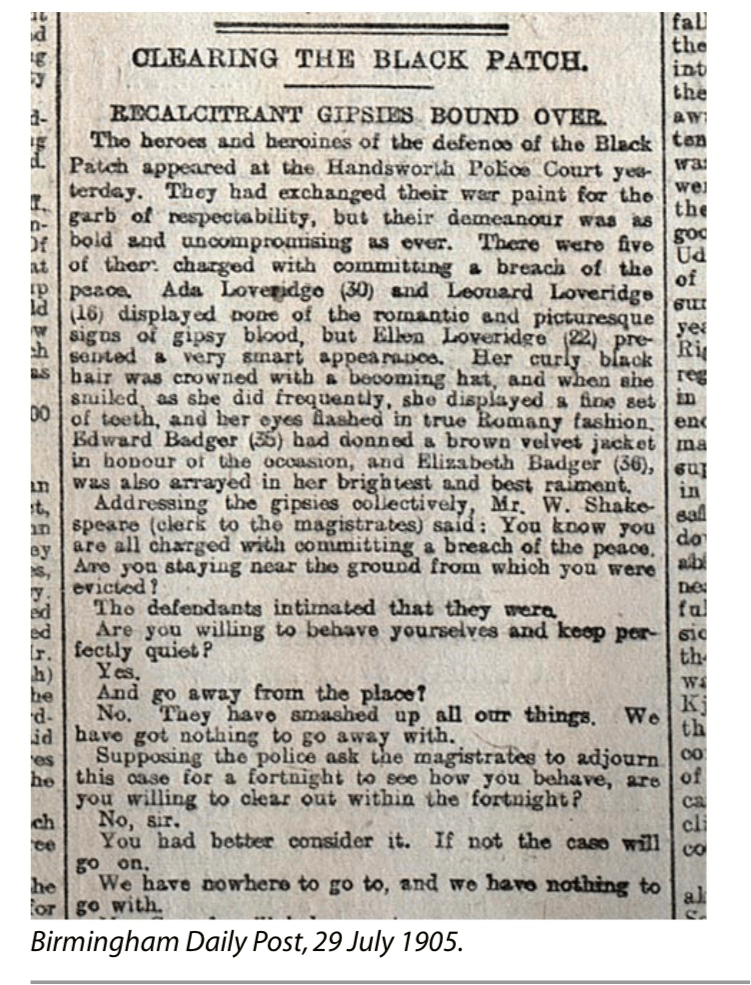

‘By order of the Peaky Blinders’: GRT History Matters

Once Gypsy Roma and Traveller (GRT) history month commences Gypsy and Traveller histories are largely ignored. This is on par with the the erasure of GRT history and contemporary culture within mainstream Britain. Given this, I was surprised that the very popular Peaky Blinders starred Birmingham based main characters and their families who appear to be Brummies, of Romany, Gypsy and Irish Traveller heritage.

In many ways representation within Peaky Blinders is problematic, it is typical that once GRT people appear as main characters their lifestyles are associated with gangs, sex and violence. But there are a lot of positives, the episodes are filled with fabulous costumes, interesting characters, plots, settings and music. There is certainly a lot of pride that comes with the representation of Birmingham based lives of mixed heritage Gypsy and Traveller families on screen.

Peaky Blinders is set in a time era which is just after WWI and appears to end in the 1930s. Whilst the series is fictional, there are many parallels that can be drawn between the lives of the fictional main character Tommy Shelby and his family and the real-life lived histories of Gypsy and Traveller people.

Peaky Blinders does well to de-mythisise the assumption that Gypsy and Traveller people do not mix with gorgers and do not participate within mainstream society. To illustrate, Tommy and his brother’s fought in WWI and experienced the damaging aftereffects of war participation. In reality, despite previously being subjected to British colonial practices and being treated with distain by the State many British Gypsy and Traveller people would have had no choice but to fight in this war due to conscription. Many would have lost their lives because of this.

Note that Tommy’s family mostly lived within housing and were working within mainstream industrial society. In reality, in industrial cities like Birmimgham many nomadic Gypsy and Traveller lifestyles would have been under threat due to land purchases made by gorgers for the purpose of building factories and housing (Green, 2009). Upon purchase of this land nomadic groups would be evicted from it, this would have left many homeless, with the increased the pressure to assimilate. This would result in work life changes, hence, Gypsy and Traveller people worked alongside gorgers in factories, where the pay and conditions would have been poor (Green, 2009).

Just like prejudice in reality, even when living within housing Tommy and his family experience prejudice from within and outside of their own community. Tommy is referred to as a ‘dirty didicoi’ seemingly due to the perception of his mixed heritage and not being of ‘full-blooded’ Gypsy stock. In response to an anti-gypsy slur Tommy mocks stereotypes by stating that as well as his day job he ‘also sells pegs and tells fortunes’.

Towards the end of Peaky Blinders the promotion of fascism by elite figures is central to the storyline. Just as in reality, there was the development of the British Union of Fascists political party. Prejudice and fascist ideas contributed to categorising Gypsys as an inferior race. Whilst Peaky Blinders ends before WWII it is harrowing to know that these ideas influenced the extermination of Roma and Gypsies during the Nazi regime. Many British Gypsy and Traveller soldiers lives would have also been lost in fighting the Nazi’s in WWII due to this.

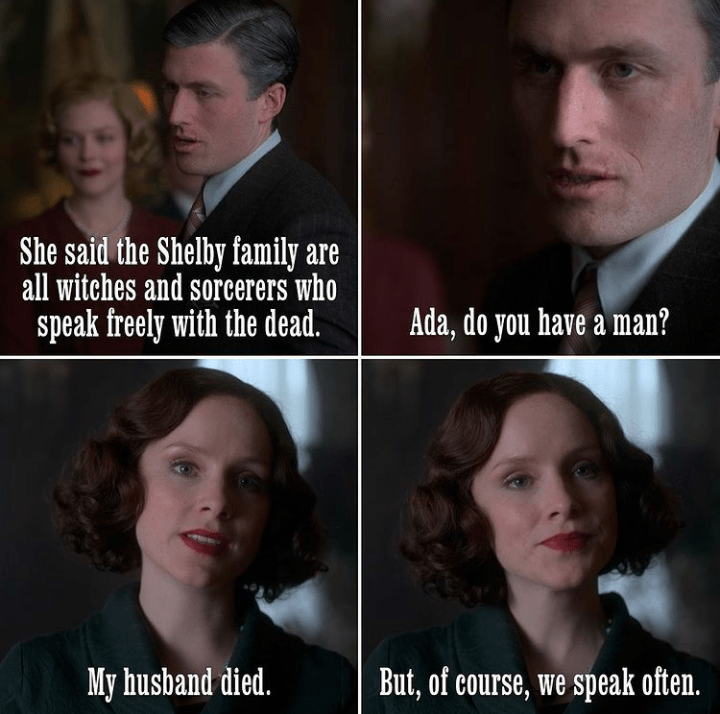

It is unfortunate that the women have less screen time in Peaky Blinders, but their personalities did shine. Ada’s character and response to prejudice is ace, whether this is responding to street hecklers, an elite eugenicist women’s ethnic cleansing ideas, or her son’s prejudice towards his sister. When her son refers to his sister as a ‘thing’ and states that she would ‘get them killed’ as she was a Black-mixed race child she responds by stating, ‘where will they send you Karl?’ whilst making him aware that he could also be subjected to persecution due to having a Jewish father and a Gypsy mother.

This year marks the end of Peaky Blinder’s episodes, the last episode is great. Tommy returns to his roots – choosing to end his days with his horse, wagon and photographs of his family. But he then wins against all the odds! Unfortunately, whilst Peaky Blinders has been celebrated there is less celebration of Gypsy and Traveller ethnicities, these were completely ignored within the documentary The Real Peaky Blinders.

Through whitewashing Gypsy and Traveller peoples histories are frequently denied. To adapt David Olusoga’s words, ‘[Gypsy and Traveller] history is British history’. An awareness of Roma Gypsy and Traveller history should not only reside with Gypsies and Travellers alone, or exist at the margins, as these are connected to all of us. As Taylor and Hinks (2021) indicate, if there is increased awareness that past and present themes of percecution this might enable increased support for Gypsy, Roma and Traveller rights – this is vital.

References:

Olusoga, D. (2016) Black and British: A forgotten History, BBC [online].

Taylor, B. and Hinks, J., (2021). What field? Where? Bringing Gypsy, Roma and Traveller History into View. Cultural and social history, 18(5), pp.629–650.

Protect international law

In criminological discourses the term “war crime” is a contested one, not because there are no atrocities committed at war, but because for some of us, war is a crime in its own right. There is an expectation that even in a war there are rules and therefore the violation of these rules could lead to war crimes. This very focused view on war is part of a wider critique of the discipline. Several criminologists including, Ruggiero, DiPietro, McGarry and Walklate, to name a few, have argued that there is less focus on war as a crime, instead war is seen more as part of a metaphor used in response to social situations.

As far back as the 1960s, US President Johnson in his state of the union address, announced “The administration today here and now declares unconditional war on poverty in America”. What followed in the 1964 Economic Opportunity Act, was seen as the encapsulation of that proclamation. In some ways this announcement was ironic considering that the Vietnam war was raging at the time, 4 years before the well documented My Lai massacre. A war crime that aroused the international community; despite the numbers of soldiers involved in the massacre, only the platoon leader was charged and given a life sentence, later commuted to three and a half years incarceration (after a presidential intervention). Anyone can draw their own conclusion if the murder of approximately 500 people and the rape of women and children is reflected in this sentence. The Vietnam war was an ideological war on communism, leaving the literal interpretation for the historians of the future. In a war on ideology the “massacre” was the “collateral damage” of the time.

After all for the administration of the time, the war on poverty was the one that they tried to fight against. Since then, successive politicians have declared additional wars, on issues namely drugs and terror. These wars are representations of struggles but not in a literal sense. In the case of drugs and terrorism criminology focused on trafficking, financing and organised crimes but not on war per se. The use of war as a metaphor is a potent one because it identifies a social foe that needs to be curtailed and the official State wages war against it. It offers a justification in case the State is accused being heavy handed. For those declaring war on issues serves by signalling their resolve but also (unwittingly or deliberately) it glorifies war as an cleansing act. War as a metaphor is both powerful and dangerous because it excuses State violence and human rights violations. What about the reality of war?

As early as 1936, W.A Bonger, recognised war as a scourge of humanity. This realisation becomes ever more potent considering in years to come the world will be enveloped in another world war. At the end of the war the international community set up the international criminal court to explore some of the crimes committed during the war, namely the use of concentration camps for the extermination of particular populations. in 1944 Raphael Lemkin, coined the term genocide to identify the systemic extermination of Jews, Roma, Slavic people, along with political dissidents and sexual deviants, namely homosexuals.

In the aftermath of the second world war, the Nuremberg trials in Europe and the Tokyo trials in Asia set out to investigate “war crimes”. This became the first time that aspects of warfare and attitudes to populations were scrutinised. The creation of the Nuremberg Charter and the outcomes of the trials formulated some of the baseline of human rights principles including the rejection of the usual, up to that point, principle of “I was only following orders”. It also resulted in the Nuremberg Code that set out clear principles on ethical research and human experimentation. Whilst all of these are worthwhile ideas and have influenced the original formation of the United Nations charter it did not address the bigger “elephant” in the room; war itself. It seemed that the trials and consequent legal discourses distanced themselves from the wider criminological ideas that could have theorised the nature of war but most importantly the effects of war onto people, communities, and future relations. War as an indiscriminate destructive force was simply neglected.

The absence of a focused criminological theory from one end and the legal representation as set in the original tribunals on the other led to a distinct absence of discussions on something that Alfred Einstein posed to Sigmund Freud in early 1930s, “Why war?”. Whilst the trials set up some interesting ideas, they were criticised as “victor’s justice”. Originally this claim was dismissed, but to this day, there has been not a single conviction in international courts and tribunals of those who were on the “victors’” side, regardless of their conduct. So somehow the focus changed, and the international community is now engaged in a conversation about the processes of international courts and justice, without having ever addressed the original criticism. Since the original international trials there have been some additional ones regarding conflicts in Yugoslavia and Rwanda. The international community’s choice of countries to investigate and potentially, prosecute has brought additional criticism about the partiality of the process. In the meantime, international justice is only recognised by some countries whilst others choose not to engage. War, or rather, war crimes become a call whenever convenient to exert political pressure according to the geo-political relations of the time. This is not justice, it is an ad hoc arrangement that devalues the very principles that it professes to protect.

This is where criminology needs to step up. We have for a long time recognised and conceptually described different criminalities, across the spectrum of human deviance, but war has been left unaccounted for. In the visions of the 19th and 20th century social scientists, a world without war was conceptualised. The technological and social advancements permitted people to be optimistic of the role of international institutions sitting in arbitration to address international conflicts. It sounds unrealistic, but at the time when this is written, we are witness to another war, whilst there are numerous theatres of wars raging, leaving a trail of continuous destruction. Instead of choosing sides, splitting the good from the bad and trying to justify a just or an unjust war, maybe we should ask, “Why war”? In relation to youth crime, Rutherford famously pondered if we could let children just grow out of crime. Maybe, as an international community of people, we should do the same with war. Grow out of the crime of war. To do so we would need to stop the heroic drums, the idolisation of the glorious dead and instead, consider the frightened populations and the long stain of a violence which I have blogged about before: The crime of war

Days to mark on our calendar!

It is common practice to have a day in the year to commemorate something. In fact, we have months that seemed to be themed with specific events. I look at the diary at the days/months which are full of causes, some incredibly important, others commemorating and then there are those more trivial. Days in a year to make a mark to remind us of things. An anniversary of events that brings something back to a collective consciousness. Once the day/month is over, we busily prepare for the next event, month and somehow between the months and days, I cannot help but wonder; what is left after the day/month?

When International Women’s Day was originally established, at the beginning of the 20th century, socialism was a driving political movement and women’s suffrage was one of the main social issues; since then other issues have been added whilst the main issue of equality remains on the cards. Has women’s movement advanced through the commemoration of International Women’s Day? Debatable if it had an impact. Originally the day was a call for strikes and the mobilisation of women workers. Today it is a day in the calendar that allows politicians to utter platitudes about how important the day is, and of course how much we respect and love women these days! It is hardly a representation of what it was or set out to be. Like so many, numerous other events are marked on our calendar, but wehave lost sight of what they were originally set out to be.

Consider the importance of a day to commemorate the Nazi Holocaust. Never again! The promise that such a mass crime should never happen; the recognition that genocide has no place in our respective societies. Since that genocide, numerous others have taken place, not to mention the mass murder, violent relocations, and the massacres and ethnic cleanings that have happened since. Somehow the “never again”, to people in Biafra, East Timor, Rwanda, Darfur, former Yugoslavia, Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Libya, and many other places simply sounds ironic! We commemorate the day, but we do not honour the spirit of that day.

In this mixture of days and months we also have days for mothers, fathers, lovers, friends, hugs, happiness, and many other national and international events. To commemorate or to offer a moment of reflection. Somehow the reflection is lost and for some of these days, millions of people are required to purchase something to demonstrate that they care or worst still, to make something! How many mothers worldwide have had to admire badly made pottery or badly drawn cards from kids who wanted to say “I love you” on one specific day. Leaves me to wonder what they would want to say on all other days!

So, is it better to forget them? Get rid of these days and if anyone suggests the creation of another, we feed them to crocodiles? It would have been easy from one point to end them all. Social issues are never easily resolved so we can recognise that a day or a month does not resolve them! It raises awareness but it’s not the solution. In the old days when the Olympics started there was a call for truce. They did not allow for the games to take place whilst a war was happening. Tokenism? Perhaps, but also the recognition that for events to have any credibility they need to go beyond words; they must have actions associated with them. What if those actions go further than the day/month of the commemoration? Imagine if we respect and honour women, not only on IWD but every day, imagine if we treat people with the respect, they deserve beyond BHM, LGBTQ+ months? Maybe it is difficult but if we recognise it to be right, we ought to try. We know that the Holocaust was a bad thing so lets not just remember it…lets avoid it from happening …Never again!