Home » University (Page 7)

Category Archives: University

Back to school; who would have thought it could be fun?

A few years ago, probably about three or four, I found myself appointed as some form of school liaison person for criminology. I’m still trying to conjure up a title for my office worthy of consideration as grand poohbah. As I understood my role, the university marketing department would arrange for schools to visit the university or for me to visit schools to promote the university and talk about criminology.

In the beginning, I stumbled around the talks, trying to find my feet and a formula of presentation that worked. As with most things, it’s trial and error and in those earlier days some of it felt like a trial, and there were certainly a few errors (nothing major, just stuff that didn’t work). The presentations became workshops, the ideas morphed from standing up and talking and asking a few questions, with very limited replies, to asking students to think about ideas and concepts and then discussing them, introducing theoretical concepts along the way. These days we try to disentangle scenarios and try to make sense of them, exploring the ideas around definitions of crime, victims and offenders.

There is nothing special about what I do but the response seems magical, there is real engagement and enthusiasm. I can see students thinking, I can see the eyes light up when I touch on topics and question society’s ideas and values. Criminology is a fascinating subject and I want everyone to know that, but most importantly I want young minds to think for themselves and to question the accepted norms. To that extent, criminology is a bit of a side show, the main gig is the notion that university is about stretching minds, seeking and acquiring knowledge and never being satisfied with what is supposedly known. I suppose criminology is the vehicle, but the driver decides how far they go and how fast.

As well as changing my style of presentation, I have also become a little more discerning in choosing what I do. I do not want to turn up to a school simply to tell pupils this is what the course looks like, these are the modules and here are a few examples of the sorts of things we teach at the university. That does nothing to build enthusiasm, it says nothing about our teaching and quite frankly, its boring, both for me and the audience.

Whilst I will turn up to a school to take a session for pupils who have been told that they have a class taken by a visitor, I much prefer those sessions where the pupils have volunteered to attend. Non-compulsory classes such as after school events are filled with students who are there because they have an interest and the enthusiasm shines through.

Whilst recognising marketing have a place in arranging school visits, particularly new ones, I have found that more of my time is taken up revisiting schools at their request. My visits have extended outside of the county into neighbouring counties and even as far as Norfolk. Students can go to university anywhere so why not spread the word about criminology anywhere. And just to prove that students are never too young to learn, primary school visits for a bit of practical fingerprinting have been carried out for a second time. Science day is great fun, although I’m not sure parents or carers are that keen on trying to clean little inky hands (I keep telling them its only supposed to be the fingers), I really must remember not to use indelible ink!

Am I a criminologist? Are you a criminologist?

I’m regularly described as a criminologist, but more loathe to self-identify as such. My job title makes clear that I have a connection to the discipline of criminology, yet is that enough? Can any Tom, Dick or Harry (or Tabalah, Damilola or Harriet) present themselves as a criminologist, or do you need something “official” to carry the title? Is it possible, as Knepper suggests, for people to fall into criminology, to become ‘accidental criminologists’ (2007: 169). Can you be a criminologist without working in a university? Do you need to have qualifications that state criminology, and if so, how many do you need (for the record, I currently only have 1 which bears that descriptor)? Is it enough to engage in thinking about crime, or do you need practical experience? The historical antecedents of theoretical criminology indicate that it might not be necessary, whilst the existence of Convict Criminology suggests that experiential knowledge might prove advantageous….

Does it matter where you get your information about crimes, criminals and criminal justice from? For example, the news (written/electronic), magazines, novels, academic texts, lectures/seminars, government/NGO reports, true crime books, radio/podcasts, television/film, music and poetry can all focus on crime, but can we describe this diversity of media as criminology? What about personal experience; as an offender, victim or criminal justice practitioner? Furthermore, how much media (or experience) do you need to have consumed before you emerge from your chrysalis as a fully formed criminologist?

Could it be that you need to join a club or mix with other interested persons? Which brings another question; what do you call a group of criminologists? Could it be a ‘murder’ (like crows), or ‘sleuth’ (like bears), or a ‘shrewdness’ (like apes) or a ‘gang’ (like elks)? (For more interesting collective nouns, see here). Organisations such as the British, European and the American Criminology Societies indicate that there is a desire (if not, tradition) for collectivity within the discipline. A desire to meet with others to discuss crime, criminality and criminal justice forms the basis of these societies, demonstrated by (the publication of journals and) conferences; local, national and international. But what makes these gatherings different from people gathering to discuss crime at the bus stop or in the pub? Certainly, it is suggested that criminology offers a rendezvous, providing the umbrella under which all disciplines meet to discuss crime (cf. Young, 2003, Lea, 2016).

Is it how you think about crime and the views you espouse? Having been subjected to many impromptu lectures from friends, family and strangers (who became aware of my professional identity), not to mention, many heated debates with my colleagues and peers, it seems unlikely. A look at this blog and that of the BSC, not to mention academic journals and books demonstrate regular discordance amongst those deemed criminologists. Whilst there are commonalities of thought, there is also a great deal of dissonance in discussions around crime. Therefore, it seems unlikely that a group of criminologists will be able to provide any kind of consensus around crime, criminality and criminal justice.

Mannheim proposed that criminologists should engage in ‘dangerous thoughts’ (1965: 428). For Young, such thinking goes ‘beyond the immediate and the pragmatic’ (2003: 98). Instead, ‘dangerous thoughts’ enable the linking of ‘crime and penality to the deep structure of society’ (Young, 2003: 98). This concept of thinking dangerously and by default, not being afraid to think differently, offers an insight into what a criminologist might do.

I don’t have answers, only questions, but perhaps it is that uncertainty which provides the defining feature of a criminologist…

References:

Knepper Paul, (2007), Criminology and Social Policy, (London: Sage)

Lea, John, (2016), ‘Left Realism: A Radical Criminology for the Current Crisis’, International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy, 5, 3: 53-65

Mannheim, Hermann, (1965), Comparative Criminology: A Textbook: Volume 2, (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul)

Young, Jock, (2003), ‘In Praise of Dangerous Thoughts,’ Punishment and Society, 5, 1: 97-107

Beyond education…

In a previous blog I wrote about the importance of going through HE as a life changing process. The hard skills of learning about a discipline and the issues, debates around it, is merely part of the fun. The soft skills of being a member of a community of people educated at tertiary level, in some cases, outweigh the others, especially for those who never in their lives expected to walk through the gates of HE. For many who do not have a history in higher education it is an incredibly difficult act, to move from differentiating between meritocracy to elitism, especially for those who have been disadvantaged all their lives; they find the academic community exclusive, arrogant, class-minded and most damning, not for them.

The history of higher education in the UK is very interesting and connected with social aspiration and mobility. Our University, along with dozens of others, is marked as a new institution that was created in a moment of realisation that universities should not be exclusive and for the few. In conversation with our students I mentioned how as a department and an institution we train the people who move the wheels of everyday life. The nurses in A&E, the teachers in primary education, the probation officers, the paramedics, the police officers and all those professionals who matter, because they facilitate social functioning. It is rather important that all our students understand that our mission statement will become their employment identity and their professional conduct will be reflective of our ability to move our society forward, engaging with difficult issues, challenging stereotypes and promoting an ethos of tolerance, so important in a society where violence is rising.

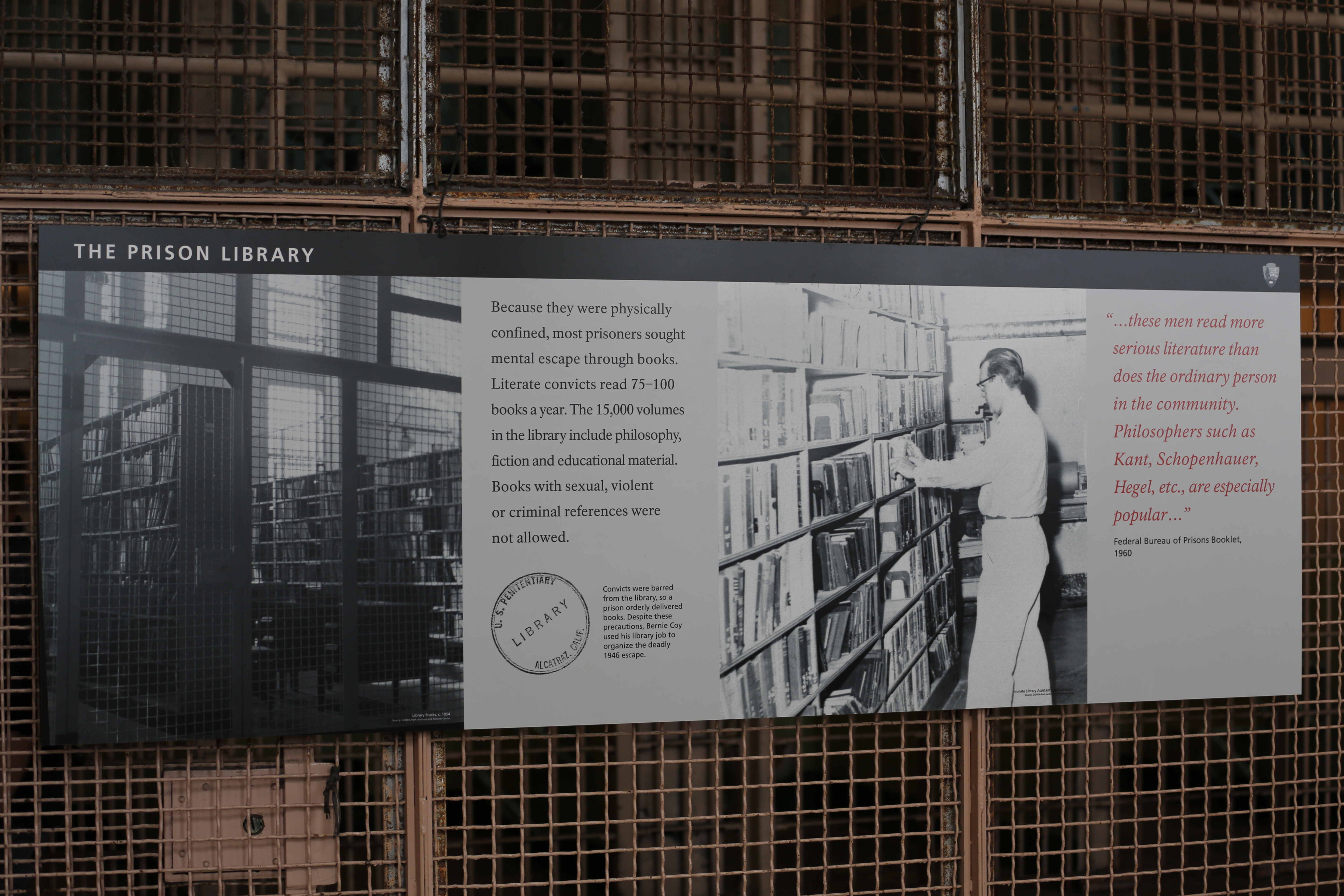

This week we had our second celebration of our prison taught module. For the last time the “class of 2019” got together and as I saw them, I was reminded of the very first session we had. In that session we explored if criminology is a science or an art. The discussion was long, and quite unexpected. In the first instance, the majority seem to agree that it is a social science, but somehow the more questions were asked, the more difficult it became to give an answer. What fascinates me in such a class, is the expectation that there is a clear fixed answer that should settle any debate. It is little by little that the realisation dawns; there are different answers and instead of worrying about information, we become concerned with knowledge. This is the long and sometimes rocky road of higher education.

Our cohort completed their studies demonstrating a level of dedication and interest for education that was inspiring. For half of them this is their first step into the world of HE whilst the other half are close to heading out of the University’s door. It is a great accomplishment for both groups but for the first who may feel they have a long way to go, I will offer the words of a greater teacher and an inspiring voice in my psyche, Cavafy’s ‘The First Step’

Even this first step

is a long way above the ordinary world.

To stand on this step

you must be in your own right

a member of the city of ideas.

And it is a hard, unusual thing

to be enrolled as a citizen of that city.

Its councils are full of Legislators

no charlatan can fool.

To have come this far is no small achievement:

what you have done already is a glorious thing

Thank you for entering this world. You earn it and from now on do not let others doubt you. You can do it if you want to. Education is there for those who desire it.

C.P. Cavafy, (1992) Collected Poems, Translated by Edmund Keeley and Philip Sherrard, Edited by George Savidis, Revised Edition, Princeton University Press, Princeton.

The Lure of Anxiety

Helen is an Associate Lecturer teaching on modules in years 1 and 3.

I wear several hats in life, but I write this blog in the role of a lecturer and a psychologist, with experience in the theory and practice of working with people with psychological disorders.

In recent years, there has been an increase in awareness of mental health problems. This is very welcome. Celebrities have talked openly about their own difficulties and high profile campaigns encourage us to bring mental health problems out of the shadows. This is hugely beneficial. When people with mental health problems suffer in silence their suffering is invariably increased, and simply talking and being listened to is often the most important part of the solution.

But with such increased awareness, there can also be well-intentioned but misguided responses which make things worse. I want to talk particularly about anxiety (which is sometimes lumped together with depression to give a diagnosis of “anxiety and depression” – they can and do often occur together but they are different emotions which require different responses). Anxiety is a normal emotion which we all experience. It is essential for survival. It keeps us safe. If children did not experience anxiety, they would wander away from their parents, put their hands in fires, fall off high surfaces or get run over by cars. Low levels of anxiety are associated with dangerous behaviour and psychopathy. High levels of anxiety can, of course, be extremely distressing and debilitating. People with anxiety disorders avoid the things they fear to the point where their lives become smaller and smaller and their experience severely restricted.

Of course we should show compassion and understanding to people who suffer from anxiety disorders and some campaigners have suggested that mental health problems should receive the same sort of response as physical health problems. However, psychological disorders, including anxiety disorders, do not behave like physical illnesses. It is not a case of diagnosing a particular “bug” and then prescribing the appropriate medication or therapy to make it go away (in reality, many physical conditions do not behave like this either). Anxiety thrives when you feed it. The temptation when you suffer high levels of anxiety is to avoid the thing that makes you anxious. But anyone who has sat through my lecture on learning theory should remember that doing something that relieves or avoids a negative consequence leads to negative reinforcement. If you avoid something that makes you highly anxious (or do something that temporarily relieves the anxiety, such as repeatedly washing your hands, or engaging in a ritual) the avoidance behaviour will be strongly reinforced. And you never experience the target of your fears, so you never learn that nothing catastrophic is actually going to happen – in other words you prevent the “extinction” that would otherwise occur. So the anxiety just gets worse and worse and worse. And your life becomes more and more restricted.

So, while we should, of course be compassionate and supportive towards people with anxiety disorders, we should be careful not to feed their fears. I remember once becoming frustrated with a member of prison staff who proudly told me how she was supporting a prisoner with obsessive-compulsive disorder by allowing him to have extra cleaning materials. No! In doing so, she was facilitating his disorder. What he needed was support to tolerate a less than spotless cell, so that he could learn through experience that a small amount of dirt does not lead to disaster. Increasingly, we find ourselves teaching students with anxiety difficulties. We need to support and encourage them, to allow them to talk about their problems, and to ensure that their university experience is positive. But we do them no favours by removing challenges or allowing them to avoid the aspects of university life that they fear (such as giving presentations or working in groups). In doing so, we make life easier in the short-term, but in the long-term we feed their disorders and make things worse. As I said earlier, we all experience anxiety and the best way to prevent it from controlling us is to stare it in the face and get on with whatever life throws at us.

Goodbye 2018….Hello 2019

Now that the year is almost over, it’s time to reflect on what’s gone before; the personal, the academic, the national and the global. This year, much like every other, has had its peaks and its troughs. The move to a new campus has offered an opportunity to consider education and research in new ways. Certainly, it has promoted dialogue in academic endeavour and holds out the interesting prospect of cross pollination and interdisciplinarity.

On a personal level, 2018 finally saw the submission of my doctoral thesis. Entitled ‘The Anti-Thesis of Criminological Research: The case of the criminal ex-servicemen,’ I will have my chance to defend this work, so still plenty of work to do.

For the Criminology team, we have greeted a new member; Jessica Ritchie and congratulated the newly capped Dr Susie Atherton. Along the way there may have been plenty of challenges, but also many opportunities to embrace and advance individual and team work. In September 2018 we greeted a bumper crop of new apprentice criminologists and welcomed back many familiar faces. The year also saw Criminology’s 18th birthday and our first inaugural “Big Criminology Reunion”. The chance to catch up with graduates was fantastic and we look forward to making this a regular event. Likewise, the fabulous blog entries written by graduates under the banner of “Look who’s 18” reminded us all (if we ever had any doubt) of why we do what we do.

Nationally, we marked the centenaries of the end of WWI and the passing of legislation which allowed some women the right to vote. This included the unveiling of two Suffragette statues; Millicent Fawcett and Emmeline Pankhurst. The country also remembered the murder of Stephen Lawrence 25 years earlier and saw the first arrests in relation to the Hillsborough disaster, All of which offer an opportunity to reflect on the behaviour of the police, the media and the State in the debacles which followed. These events have shaped and continue to shape the world in which we live and momentarily offered a much-needed distraction from more contemporaneous news.

For the UK, 2018 saw the start of the Grenfell Tower Inquiry, the Windrush scandal, the continuing rise of the food bank, the closure of refuges, the iniquity of Universal Credit and an increase in homelessness, symptoms of the ideological programmes of “austerity” and maintaining a “hostile environment“. All this against a backdrop of the mystery (or should that be mayhem) of Brexit which continues to rumble on. It looks likely that the concept of institutional violence will continue to offer criminologists a theoretical lens to understand the twenty-first century (cf. Curtin and Litke, 1999, Cooper and Whyte, 2018).

Internationally, we have seen no let-up in global conflict, the situation in Afghanistan, Iraq, Myanmar, Syria, Yemen (to name but a few) remains fraught with violence. Concerns around the governments of many European countries, China, North Korea and USA heighten fears and the world seems an incredibly dangerous place. The awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to Denis Mukwege and Nadia Murad offers an antidote to such fears and recognises the powerful work that can be undertaken in the name of peace. Likewise the deaths of Professor Stephen Hawking and Harry Leslie Smith, both staunch advocates for the NHS, remind us that individuals can speak out, can make a difference.

To my friends, family, colleagues and students, I raise a glass to the end of 2018 and the beginning of 2019:

‘Let’s hope it’s a good one, without any fear’ (Lennon and Ono, 1974).

References:

Cooper, Vickie and Whyte, David, (2018), ‘Grenfell, Austerity and Institutional Violence,’ Sociological Research Online, 00, 0: 1-10

Curtin, Deane and Litke, Robert, (1999) (Eds), Institutional Violence, (Amsterdam: Rodopi)

Lennon, John and Ono, Yoko, (1974) Happy Xmas (War is Over), [CD], Recorded by John and Yoko: Plastic Ono Band in Shaved Fish. PCS 7173, [s.l.], Apple

Have you been radicalised? I have

On Tuesday 12 December 2018, I was asked in court if I had been radicalised. From the witness box I proudly answered in the affirmative. This was not the first time I had made such a public admission, but admittedly the first time in a courtroom. Sounds dramatic, but the setting was the Sessions House in Northampton and the context was a Crime and Punishment lecture. Nevertheless, such is the media and political furore around the terms radicalisation and radicalism, that to make such a statement, seems an inherently radical gesture.

So why when radicalism has such a bad press, would anyone admit to being radicalised? The answer lies in your interpretation, whether positive or negative, of what radicalisation means. The Oxford Dictionary (2018) defines radicalisation as ‘[t]he action or process of causing someone to adopt radical positions on political or social issues’. For me, such a definition is inherently positive, how else can we begin to tackle longstanding social issues, than with new and radical ways of thinking? What better place to enable radicalisation than the University? An environment where ideas can be discussed freely and openly, where there is no requirement to have “an elephant in the room”, where everything and anything can be brought to the table.

My understanding of radicalisation encompasses individuals as diverse as Edith Abbott, Margaret Atwood, Howard S. Becker, Fenner Brockway, Nils Christie, Angela Davis, Simone de Beauvoir, Paul Gilroy, Mona Hatoum, Stephen Hobhouse, Martin Luther King Jr, John Lennon, Primo Levi, Hermann Mannheim, George Orwell, Sylvia Pankhurst, Rosa Parks, Pablo Picasso, Bertrand Russell, Rebecca Solnit, Thomas Szasz, Oscar Wilde, Virginia Woolf, Benjamin Zephaniah, to name but a few. These individuals have touched my imagination because they have all challenged the status quo either through their writing, their art or their activism, thus paving the way for new ways of thinking, new ways of doing. But as I’ve argued before, in relation to civil rights leaders, these individuals are important, not because of who they are but the ideas they promulgated, the actions they took to bring to the world’s attention, injustice and inequality. Each in their own unique way has drawn attention to situations, places and people, which the vast majority have taken for granted as “normal”. But sharing their thoughts, we are all offered an opportunity to take advantage of their radical message and take it forward into our own everyday lived experience.

Without radical thought there can be no change. We just carry on, business as usual, wringing our hands whilst staring desperate social problems in the face. That’s not to suggest that all radical thoughts and actions are inherently good, instead the same rigorous critique needs to be deployed, as with every other idea. However rather than viewing radicalisation as fundamentally threatening and dangerous, each of us needs to take the time to read, listen and think about new ideas. Furthermore, we need to talk about these radical ideas with others, opening them up to scrutiny and enabling even more ideas to develop. If we want the world to change and become a fairer, more equal environment for all, we have to do things differently. If we cannot face thinking differently, we will always struggle to change the world.

For me, the philosopher Bertrand Russell sums it up best

Thought is subversive and revolutionary, destructive and terrible; thought is merciless to privilege, established institutions, and comfortable habits; thought is anarchic and lawless, indifferent to authority, careless of the well-tried wisdom of the ages. Thought looks into the pit of hell and is not afraid. It sees man, a feeble speck, surrounded by unfathomable depths of silence; yet it bears itself proudly, as unmoved as if it were lord of the universe. Thought is great and swift and free, the light of the world, and the chief glory of man (Russell, 1916, 2010: 106).

Reference List:

Russell, Bertrand, (1916a/2010), Why Men Fight, (Abingdon: Routledge)

Questions, questions, questions…..

Over the last two weeks we have welcomed new and returning students to our brand-new campus. From the outside, this period of time appears frenetic, chaotic, and incredibly noisy. During this period, I feel as if I am constantly talking; explaining, indicating, signposting, answering questions and offering solutions. All of this is necessary, after all we’re all in a new place, the only difference is that some of us moved in before others. This part of my role has, on the surface, little to do with Criminology. However, once the housekeeping is out of the way we can move to more interesting criminological discussion.

For me, this focuses on the posing of questions and working out ways in which answers can be sought. It’s a common maxim, that within academia, there is no such thing as a silly question and Criminology is no exception (although students are often very sceptical). When you are studying people, everything becomes complicated and complex and of course posing questions does not necessarily guarantee a straightforward answer. As many students/graduates over the years will attest, criminological questions are often followed by yet more criminological questions… At first, this is incredibly frustrating but once you get into the swing of things, it becomes incredibly empowering, allowing individual mental agility to navigate questions in their own unique way. Of course, criminologists, as with all other social scientists, are dependent upon the quality of the evidence they provide in support of their arguments. However, criminology’s inherent interdisciplinarity enables us to choose from a far wider range of materials than many of our colleagues.

So back to the questions…which can appear from anywhere and everywhere. Just to demonstrate there are no silly questions, here are some of those floating around my head currently:

- This week I watched a little video on Facebook, one of those cases of mindlessly scrolling, whilst waiting for something else to begin. It was all about a Dutch innovation, the Tovertafel (Magic Table) and I wondered why in the UK, discussions focus on struggling to feed and keep our elders warm, yet other countries are interested in improving quality of life for all?

- Why, when with every fibre of my being, I abhor violence, I am attracted to boxing?

3. Why in a supposedly wealthy country do we still have poverty?

4. Why do we think boys and girls need different toys?

5. Why does 50% of the world’s population have to spend more on day-to-day living simply because they menstruate?

6. Why as a society are we happy to have big houses with lots of empty rooms but struggle to house the homeless?

7. Why do female ballroom dancers wear so little and who decided that women would dance better in extremely high-heeled shoes?

This is just a sample and not in any particular order. On the surface, they are chaotic and disjointed, however, what they all demonstrate is my mind’s attempt to grapple with extremely serious issues such as inequality, social deprivation, violence, discrimination, vulnerability, to name just a few.

So, to answer the question posed last week by @manosdaskalou, ‘What are Universities for?’, I would proffer my seven questions. On their own, they do not provide an answer to his question, but together they suggest avenues to explore within a safe and supportive space where free, open and academic dialogue can take place. That description suggests, for me at least, exactly what a university should be for!

And if anyone has answers for my questions, please get in touch….