Home » Truth

Category Archives: Truth

Leading with Integrity: Standing Firm Against the Echo Chamber

Sallek Yaks Musa

Truth hurts. Few appreciate it, and even fewer defend it when it threatens comfort or convention. My understanding of this reality came through personal experience, an early lesson in leadership that continues to shape how I view authority and the dangerous allure of sycophancy.

Two decades ago, my journey into education began in an unusual way. For five years, my father had spoken passionately about his dream to establish a nursery, primary, and secondary school that would help transform the state of education in our city. In 2004, we finally decided to bring that dream to life. What followed was both the beginning of my passion for education and my first encounter with the complexity of leading people and institutions.

The process of establishing the school was neither smooth nor simple. I remember every detail – the struggle to develop infrastructure that met required standards and equip it, the endless paperwork, the defence of proposals before career bureaucrats, and the scrutiny of regulatory inspections. Each stage tested our patience and resolve, yet the experience became invaluable. It offered me lessons no textbook could teach and laid the solid foundation of my leadership philosophy.

By the time we received approval to open in September 2005, I led over a hundred interviews to staff the school. That period sharpened my ability to read people and situations intuitively, a skill I have trusted ever since. The school went on to succeed beyond expectation: self-sustaining, thriving, and impacting tens of thousands of young lives. Yet, behind this success lay one central principle – truth.

My commitment to truth shaped the school’s ethos. Every decision, from recruitment to remuneration, from board meetings to relationships with parents and staff, was guided by sincerity. My academic training would later frame this conviction in philosophical terms. With leadership, I align with Auguste Comte’s positivist epistemology, rooted in the belief that truth is objective, concrete, and independent of social interpretation. This, I discovered, is easier preached than practised.

In practice, truth is disruptive. It offends vanity, challenges comfort, and exposes deception. My insistence on it often placed me in direct opposition to others on the Board, including my father. He later confided that while my defiance was difficult to bear, it forced him to confront realities he had overlooked. I further learned that the defender of truth often stands alone. My father eventually recognised what I had resisted all along: the quiet but corrosive power of flattery.

Sycophancy, though rarely discussed openly, remains one of the greatest dangers to leadership. It thrives where authority is unquestioned, and dissent discouraged. Flattery seduces leaders into believing they are infallible. It builds an echo chamber that filters information, reinforcing biases and creating an illusion of competence. Over time, this isolation from reality becomes costly as decisions are made on false premises, honest critics are sidelined, and mediocrity is rewarded over merit. But this is not a modern affliction.

The 16th-century political theorist Niccolò Machiavelli, in The Prince, warned rulers of this very danger. He cautioned that the wise Prince must deliberately surround himself with people courageous enough to speak the truth, for flatterers ‘take away the liberty of judgment.’ Centuries later, the philosopher Hannah Arendt would echo this concern, arguing that the loss of truth in public life leads to moral decay and political collapse. The persistence of these warnings shows how deeply entrenched sycophancy remains in systems of power.

The psychology behind flattery is deceptively simple. It feeds the ego, providing comfort that masquerades as respect and support. Leaders, craving affirmation, often mistake it for loyalty. But as Daniel Kahneman and other cognitive theorists have shown, human judgment is easily distorted by bias and praise. Flattery, therefore, becomes not merely a social nicety but a psychological trap, one that blinds decision-makers to inconvenient truths.

For those newly stepping into student’s course representative roles, these lessons carry special relevance. Academic leadership is often less about authority and more about stewardship, the quiet work of creating conditions where ideas can flourish, student’s voices are heard, and students can contribute honestly. Resist the temptation to surround yourself with agreeable voices. Encourage critique, invite dissent, and create a culture where questioning is not perceived as confrontation but as commitment to excellence. The strength of representation lies not in the leader’s popularity but in their willingness to confront complexity, admit limits, and make decisions grounded in truth rather than convenience.

As the once “baby school” turned twenty this year, its anniversary passed in my absence. My father’s message of appreciation reached me nonetheless, and his words reminded me why truth, though often costly, remains indispensable to authentic leadership. He wrote:

Remember, son, true leadership lies in listening attentively, sieving facts from noise, embracing unpopular voices, acting on truth, and valuing others above yourself.

That reflection closed a circle that began two decades ago. It reminded me that leadership rooted in truth is not about being right but about being realistic. It is about creating space where honesty thrives, even when it unsettles.

Flattery may offer short-term peace, but truth builds long-term strength and relationships. The leader who welcomes honesty, however uncomfortable, not only guards against failure but also nurtures a culture of integrity that outlives their term.

Twenty years after that first bold step into education, leading teams and managing academic programmes in education, I remain convinced that truth is not a luxury in leadership – it is its lifeline. Legacies are not defined by applause or position, but by the integrity to lead with sincerity, listen without fear, and act with unwavering commitment to what is right. People are ultimately remembered not for simply opposing flattery, but for the truth they championed and the courage they demonstrated to stand firm in their convictions when it mattered most.

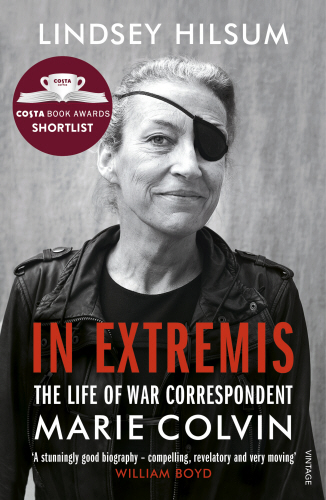

A review of In-Extremis: The Life of War Correspondent Marie Colvin

Recently, I picked up a book on the biography of Marie Colvin, a war correspondent who was assassinated in Syria, 2012. Usually, I refrain from reading biographies, as I consider many to be superficial accounts of people’s experiences that are typically removed from wider social issues serving no purpose besides enabling what Zizek would call a fetishist disavowal. It is the biographies of sports players and singers, found on the top shelves of Waterstones and Asda that spring to mind. In-Extremis, however, was different. I consider this book to be a very poignant and captivating biography of war correspondent Marie Colvin, authored by fellow journalist Lindsey Hilsum. The book narrates Marie’s life before her assassination. Her early years, career ventures, intimate relationships, friendships, and relationships with drugs and alcohol were all discussed. So too were the accounts of Marie’s fearless reporting from some of the world’s most dangerous conflict zones, including Sri-Lanka, Iraq, Lebanon, and Syria. Hilsum wrote on the events both before Marie’s exhilarating career and during the peak of her war correspondence to illustrate the complexities in her life. This reflected on Marie’s insatiability of desire to tell the truth and capture the voices of those who are absent from the ‘script’. So too, reporting on the emotions behind war and conflict in addition to the consistent acts of personal sacrifice made in the name of Justice for the disenfranchised and the voiceless.

Across the first few chapters, Hilsum wrote on the personal life of Marie- particularly her traits of bravery, resilience, persistence, and an undying quest for the truth. Hilsum further delved into the complexities of Marie’s personality and life philosophies. A regular smoker, drinker and partygoer with a captivating personality that drew people in were core to who Marie was according to Hilsum. However, the psychological toils of war reporting became clear, particularly as later in the book, the effects of Marie’s PTSD and trauma began to present itself, particularly after Marie lost eyesight in her left eye after being shot in Sri-Lanka. The eye-patch worn by Marie to me symbolised the way she carried the burdens of her profession and personal vulnerabilities, particularly between maintaining her family life and navigating her occupational hazards.

In writing this biography, Hilsum not only mapped the life of one genuinely awesome and inspiring woman, but also highlighted the importance of reporting and capturing the voices of the casualties of war. Much of her work, I felt resonated with my own. As an academic researcher, it is my job to research on real-life issues and to seek the truth. I resonated with Marie’s quest for the truth and strongly aligned myself to her principles on capturing the lived experiences of those impacted by war, conflict, and social justice issues. These people, I consider are more qualified to discuss these issues than those of us who sit in the ivory towers of institutions (me included!).

Moreover, I considered how I can be more like Marie and how I can embed her philosophies more so into my own research… whether that’s through researching with communities on the cost-of-living crisis or disseminating my research to students, fellow academics, policymakers, and practitioners. I feel inspired and moving forward, I seek to embody the life and spirit of Marie and thousands of other journalists and academics who work tirelessly to research on and understand the truth to bring forward the narratives of those who are left behind and discarded by society in its mainstream.

April Showers: so many tears

What does April mean to you? April showers as the title would suggest, April Fools which I detest, or the beginning of winter’s rest? Today I am going to argue that April is the most criminogenic month of the year. No doubt, my colleagues and readers will disagree, but here goes….

What follows is discussion on three events which apart from their occurrence in the month of April are ostensibly unrelated. Nevertheless, scratch beneath the surface and you will see why they are so important to the development of my criminological understanding, forging the importance I place on social justice.

On 15 April 1912, RMS Titanic sank to the bottom of the sea, with more than 1,500 lost lives. We know the story reasonably well, even if just through film. Fewer people are aware that this tragedy led to inquiries on both sides of the Atlantic, as well, as Limitation of Liability Hearings. These acknowledged profound failings on the part of White Star and made recommendations primarily relating to lifeboats, staffing and structures of ships. Each of these were to be enshrined in law. Like many institutional inquiries these reports, thankfully digitised so anyone can read them, are very dry, neutral, inhumane documents. There is very little evidence of the human tragedy, instead there are questions and answers which focus on procedural and engineering matters. However, if you look carefully, there are glimpses of life at that time and criminological questions to be raised.

The table below is taken from the British Wreck Commissioners Inquiry Report and details both passengers and staff onboard RMS Titanic. This table allows us to do the maths, to see how many survived this ordeal. Here we can see the violence of social class, where the minority take precedence over the majority. For those on that ship and many others of that time, your experiences could only be mediated through a class based system. Yet when that ship went down, tragedy becomes the great equaliser.

On 15th April, 1989 fans did as they do (pandemics aside) every Saturday during the football season, they went to the game. On that sunny spring day, Liverpool Football Club were playing Nottingham Forest, both away from home and over 50,000 fans had travelled some distance to watch their team with family and friends. Tragically 96 of those fans died that day or shortly after. @anfieldbhoy has written a far more extensive piece on the Hillsborough Disaster and I don’t plan to revisit the details here. Nevertheless, as with RMS Titanic, questions were asked in relation to the loss of life and institutional or corporate failings which led to this tragedy. Currently it is not possible to access the Taylor Report due to ongoing investigation, but it makes for equally dry, neutral and inhuman, reading. It is hard to catch sight of 96 lives in pages dense with text, focused on answering questions that never quite focus on what survivors and families need. The Hillsborough Independent Panel [HIP] is far more focused on people as are the Inquests (also currently unavailable) which followed. Criminologically, HIP’s very independence takes it outside of powerful institutions. So whilst it can “speak truth to power” it has no ability to coerce answers from power or enforce change. For the survivors and family it brings some respite, some acknowledgement that what happened that day should have never have happened. However, for those individuals and wider society, there appears to be no semblance of justice, despite the passing of 32 years.

On 22 April 1993, Stephen Lawrence was murdered. He was the victim of a horrific, racially motivated, violent assault by a group of young white man. This much was known, immediately to his friend Duwayne Brooks, but was apparently not clear to the attending police officers. Instead, as became clear during the Stephen Lawrence Inquiry the police investigation was riddled with institutional racism from the outset. The Macpherson report (1999) tries extremely hard to keep focus on Stephen Lawrence as a human being, try to read the evidence given by Duwayne Brooks and Stephen’s parents without shedding a tear. However, much of the text is taken is taken up with procedural detail, arguments and denial. In 2012 two of the men who murdered Stephen Lawrence were found guilty and sentenced to be detained under Her Majesty’s pleasure (both were juveniles in 1993). Since 1999, when the report was published we’ve learnt even more about the police’s institutional racism and their continual attacks on Stephen’s family and friends designed to undermine and harm. So whilst institutions can be compelled to reflect upon their behaviour and coerced into recognising the need for change, for evolution, in reality this appears to be a surface activity. Criminologically, we recognise that Stephen was the victim of a brutal crime, some, but not all, of those that carried out the attack have been held accountable. Justice for Stephen Lawrence, albeit a long time coming, has been served to some degree. But what about his family? Traumatised by the loss of one of their own, a child who had been nurtured to adulthood, loved and respected, this is a family deserving of care and support. What about the institutions, the police, the government? It seems very much business as usual, despite the publication of Lammy (2017) and Williams (2018) which provide detailed accounts of the continual institutional racism within our society. Instead, we have the highly criticised Sewell Report (2021) which completely dismisses the very idea of institutional racism. I have not linked to this document, it is beneath contempt, but if you desperately want to read it, a simple google search will locate it.

In each of the cases above and many others, we know instinctively that something is fundamentally wrong. That what has happened has caused such great harm to individuals, families, communities, that it must surely be a crime. But a crime as we commonly understand it involves victim(s) and perpetrator(s). If the Classical School of Criminology is to be believed, it involves somebody making a deliberate choice to do harm to others to benefit ourselves. If there is a crime, somebody has to pay the price, whatever that may be in terms of punishment. We look to the institutions within our society; policing, the courts, the government for answers, but instead receive official inquiries that appear to explore everything but the important questions. As a society we do not seem keen to grapple with complexity, maybe it’s because we are frightened that our institutions will also turn against us?

The current government assures us that there will be an inquiry into their handling of the pandemic, that there will be some answers for the families of the 126,000 plus who have died due to Covid-19. They say this inquiry will come when the time is right, but right for who?

Maybe you can think of other reasons why April is a criminologically important month, or maybe you think there are other contenders? Either way, why not get in touch?

A pit and no pendulum

Laughter is a great healer; it makes us forget miserable situations, fill us with endorphins, decreases our stress and make us feel better. Laughter is good and we like people that make us laugh. Comedians are like ugly rock-stars bringing their version of satire to everyday situations. Some people enjoy situational comedy, with a little bit of slapstick, others like jokes, others enjoy parodies on familiar situations. Hard to find a person across the planet that does not enjoy a form of comedy. In recent years entertainment opened more venues for comedy, programmes on television and shows on the theatres becoming quite popular among so many of us.

In comedy, political satire plays an important part to control authority and question the power held by those in government. People like to laugh at people in power, as a mechanism of distancing themselves from the control, they are under. The corrosive property of power is so potent that even the wisest leaders in power are likely to lose control or become more authoritarian. Against that, satire offers some much needed relief on cases of everyday political aggression. To some people, politics have become so toxic that they can only follow the every day events through the lens of a comedian to make it bearable.

People lose their work, homes and even their right to stay in a country on political decisions made about them. Against these situations, comedy has been an antidote to the immense pain they face. Some politicians are becoming aware of the power comedy has and employ it, whilst others embrace the parody they receive. It was well known that a US president that accepted parody well was Ronald Reagan. On the other end, Boris Johnson embraced comedy, joining the panel of comedy programmes, as he was building his political profile. Tony Blair and David Cameron participated in comedy programmes for charity “taking the piss” out of themselves. These actions endear the leaders to the public who accept the self-deprecating attitude as an acknowledgment of their fallibility.

The ability to humanise leaders is not new, but mass media, including social media, make it more possible now. There is nothing wrong with that, but it is something that, like smoking, should come with some health warnings. The politicians are human, but their politics can sometimes be unfair, unjust or outright inhuman. A person in power can make the decision to send people to war and ultimately lead numerous people to death. A politician can take the “sensible option” to cut funding to public spending directed at people who may suffer consequently. A leader can decide on people’s future and their impact will be long lasting. The most important consequence of power is the devastation that it can cause as the unanticipated consequence of actions. A leader makes the decision to move people back into agriculture and moves millions to farms. The consequence; famine. A leader makes the decision not to accept the results of an election; a militia emerges to defend that leader. The political system is trying to defend itself, but the unexpected consequences will emerge in the future.

What is to do then? To laugh at those in power is important, because it controls the volume of power, but to simply laugh at politicians as if they were comedians, is wrong. They are not equivalent and most importantly we can “take the piss” at their demeanour, mannerisms or political ideology, but we need to observe and take their actions seriously. A bad comedian can simply ruin your night, a bad politician can ruin your life.

The power of the written word: fact, fiction and reality

The written word is so powerful, crucial to our understanding and yet so easily abused. So often what gets written is unregulated, even when written in the newspapers. Whilst the press is supposedly regulated independently, we have to question how much regulation actually occurs. Freedom of the press is extremely important, so is free speech but I do wonder where we draw the line. Is freedom of speech more important than regulating damaging vitriolic hyperbole and rhetoric? Is freedom of speech more important than truth?

We only have to read some of the sensationalist headlines in some newspapers to realise that the truth is less important than the story. What we read in papers is about what sells not about reality. The stories probably tell us more about the writer and the editor than anything else. We more often than not know nothing about the circumstances or individuals that are being written about. Stories are told from the viewpoint of others that purport to be there, or are an ‘expert’ in a particular field. The stories are just that, stories, they may represent one person’s reality but not another’s. Juicy parts are highlighted, the dull and boring downplayed. Whilst this can be aimed at newspapers, can the same not be said about other forms of media?

A few weeks ago, I was paging through LinkedIn on my phone catching up with the updates I had missed. Why I have LinkedIn I don’t really know. I think its because a long time ago when I was about to go job hunting someone told me it was a good idea. Anyway, I digress, what caught my eye was a number of people congratulating Rachel Swann on becoming the next Chief Constable of Derbyshire. I recognised her from the news, remember the story when the dam was about to burst?

It wasn’t the fact that she’d been promoted that caught my eye, it was the fact that someone had written that she should ignore the trolls on Twitter. I had a quick look to see what they were on about. To say they were vitriolic is an understatement. But all of the comments based her ability to do the job on her looks and her sexuality. I thought to myself at the time, how do you get away with this? I doubt that any of those people that wrote those comments have any idea about her capabilities. Unkind, rude and I dare say hurtful comments, made that are totally unregulated. The comments say more about the writers than they do about Rachel Swann. You don’t get to the position of Assistant Chief Constable let alone Chief Constable without having displayed extraordinary qualities.

And then I think about Twitter and the nonsense that people are allowed to write on this medium. President Trump is a prime example. There isn’t a day that goes by without him writing some vitriolic nonsense about someone or some nation. Barack Obama used to be in his sights and now it’s Joe Biden. I know nothing about any of them, but if I follow the Trump twit feed, they are incompetent fools and disaster looms if Biden is elected as president. As I said before, sometimes what is written says more about the writer than anyone else.

I’m conscious that I’m writing this for a blog and many that read it don’t know me. Blogs are no different to other media outlets. If I am to criticise others for what they have written, then I ought to be careful about what I write and how. I have strong views and passionately believe in free speech, but I do not believe that the privilege I have been given allows me to be hurtful to others. My views are my views and sometimes I think readers get a little glimpse of the real me, the chances are they have a better idea about me than what I am writing about. I write with a purpose and often from the heart, but I try not to be unkind nor stretch the truth or tell outright lies. I value my credibility and if I believe that people know more about me than the story, I owe it to myself to try to be true to my values. I just wish sometimes that when people write for the newspapers, post comments on Twitter or write blogs that they thought about what they are writing and indulged in a bit of self-reflection. Maybe they don’t because they wont like what they see.

Betty Broderick

I’m sure many of you are aware of the Dirty John series two, Betty Broderick. Although it has not had as much coverage as I’d have hoped. Now true crime documentaries are not always the best way to find out the truth, after delving deep into the history of this case, I found it does represent it well. If you haven’t given it a watch, I would definitely recommend it and would love to know your thoughts on the case.

Betty was married to Daniel Broderick, having 4 children and helping him become a doctor and then through law school. Of course, it all ended in 1989 when Betty had finally had enough of the torturous years with her husband’s affair with Linda Kolkena, killing them both. Not that I am condoning what she did at all, it was wrong for her to end his and Linda’s life. Although I do understand why she did do it and believe others in her situation could be led to this end too. After she kept them afloat with money while he went through law school, having his children and being the perfect housewife, he decided she was too old and needed a young wife to suit his new high class life-style.

This is not to say that Daniel was the sole person to blame, Betty was in the wrong too. However, taking a woman’s children away from her and brainwashing them tipped her over the edge, as it would do with many women. Betty brought the children up alone, with Daniel always too busy with his company to care about them. It seems Daniel did love Betty to begin with, but to me, it seems it became easy and stayed with her to do everything for him.

Daniel began socialising with his new girlfriend, rubbing his success in Betty’s face. This really does make me sad for Betty, she had no money because all her time was invested in her husband’s career. When it came to the divorce, it became a game for Daniel, trying to leave her with next to nothing and only supervised visits with her own children. He really did drive her to the point of destruction.

This woman is now 72 and has been in prison since 1989. I may be too generous, but I believe that this woman should be let to live her final years as a free woman. Free from having to fight for her children, fight for money to live and fight for her sanity. Daniel took all these away from her. And, although he did not get to live, Betty merely existed in the years of their divorce. She lost her spark and became depressed.

What do you believe?

Information overload

If you’re anything like me, the last few weeks you’ve probably found yourself fighting your way through a tsunami of information that’s coming from all directions. Notifications are going into overdrive with social media apps, news apps and browsers desperate to deliver more and more content, at ever increasing frequencies. Add to this all the stories, videos and memes friends and family are also sharing and it’s hard to know where to look first. The sheer volume of content makes it harder than ever to know what is fact, fake or opinion. In honesty, it can all be a bit overwhelming.

How do you even begin sorting the information that’s being thrown at you when you can’t keep up with how quickly your news feeds are moving

1. Sort the fact from the fiction

There’s nothing like a pandemic to send the fake news mills into overdrive. Many are easy to spot, the 2020 version of an urban myth (My neighbour’s, brother’s dog is a top civil servant and says….) others are much more sophisticated and purport to be from trusted sources. The Guardian (Mercier, 2020) reports on the danger of these stories and the tragic consequences that can occur when people believe them.

Why are we so susceptible to fake news stories though? They use “truthiness” to play on our fears and biases. If it sounds like something we think could be true, if it confirms our prejudices or worries, we’re more likely to believe it.

Fact checking is more important than ever. Take a moment to think before you share – what is the source? where are their sources? For more tips on spotting fake news check out this guide (IFLA, 2020) or use an independent reputable fact checking site such as Full Fact. This blog article from the Information Literacy Group (Bedford, 2020) pulls together a selection of reliable information sources related to Covid-19.

2. Bursting your bubble

Personalised content from news feeds can be useful, but we often don’t even realise the news stories and content we’re seeing in apps has been chosen by an algorithm. Their purpose is to feed us stories they think we will like, to keep us reading longer. This can be convenient, but it can also be misleading. We get trapped in a filter bubble that feeds us the type of content we like and usually from a perspective that agrees with our own way of thinking.

Sometimes we need to know what else is going on in the world outside our specific areas of interest though and sometimes we need to consider viewpoints we don’t necessarily agree with, so we can make an informed judgement.

These algorithms can also get things wrong. My own Google news feed weirdly seems to think I’m interested in anything vaguely related to British Airways, Coventry City Football Club and Meghan Markle (I’d like to state for the record I’m not particularly interested in any of these things). This is without considering the inherent biases they have built into them, before they even start their work (algorithm bias is a whole other blog article in itself).

It’s human nature to want to hear things that agree with our way of thinking and reinforce our own world view, we follow people we like and admire, we choose news sources that confirm our way of thinking, but there is a risk of missing the bigger picture when sat in our bubble. Rather than letting the news come to you, go direct to several news sources (maybe even some that have a different political leaning to you, if you feel like being challenged). Be active in seeking news stories, rather than passively consuming them.

3. Step away from the news feed (when you need to)

It’s a bit of a balancing act, we need to know enough to be informed and stay safe without spending 24/7 plugged in. We’re not superhuman though and sometimes we need to accept that just because it’s on our feed, we’re not obliged to engage. Give yourself permission to skip stories, mute notifications and be selective when you need to. We all have different saturation points, mine will vary day to day, but listen to yourself and know when it’s time to switch off. If it helps, set reminders on your apps to give you a nudge when you’ve spent a certain amount of time on them. The Mental Health Foundation (2020) have some tips for looking after your mental health in relation to news coverage of Covid-19.

If you need help finding information or want support evaluating sources the Academic Librarian team are offering online tutorials and an online drop-in service. You can also contact us by emailing librarians@northampton.ac.uk

Cheryl Gardner

Academic Liaison Manager, LLS

References

Bedford, D. (2020) Covid-19: Seeking reliable information in difficult times. Information Literacy Group [online]. Available from: https://infolit.org.uk/covid-19-seeking-reliable-information-in-difficult-times/ [Accessed 31/03/2020].

IFLA (2020) How to spot fake news. IFLA [online]. Available from: https://www.ifla.org/publications/node/11174 [Accessed 31/03/2020].

Mental Health Foundation (2020) Looking after your mental health during the Coronavirus outbreak. Mental Health Foundation [online]. Available from: https://mentalhealth.org.uk/publications/looking-after-your-mental-health-during-coronavirus-outbreak [Accessed 31/03/2020]

Mercier, H. (2020) Fake news in the time of coronavirus: how big is the threat? The Guardian [online]. 30th March. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/mar/30/fake-news-coronavirus-false-information [Accessed 31/03/2020].

“Truth” at the age of uncertainty

Research methods taught for undergraduate students is like asking a young person to eat their greens; fraught with difficulties. The prospect of engaging with active research seems distant, and the philosophical concepts underneath it, seem convoluted and far too complex. After all, at some point each of us struggled with inductive/deductive reasoning, whilst appreciating the difference between epistemology over methodology…and don’t get me stated on the ontology and if it is socially proscribed or not…minefield. It is through time, and plenty of trial and error efforts, that a mechanism is developed to deliver complex information in any “palatable” format!

There are pedagogic arguments here, for and against, the development of disentangling theoretical conventions, especially to those who hear these concepts for the first time. I feel a sense of deep history when I ask students “to observe” much like Popper argued in The Logic of Scientific Discovery when he builds up the connection between theory and observational testing.

So, we try to come to terms with the conceptual challenges and piqued their understanding, only to be confronted with the way those concepts correlate to our understanding of reality. This ability to vocalise social reality and conditions around us, is paramount, on demonstrating our understanding of social scientific enquiry. This is quite a difficult process that we acquire slowly, painfully and possibly one of the reasons people find it frustrating. In observational reality, notwithstanding experimentation, the subjectivity of reality makes us nervous as to the contentions we are about to make.

A prime skill at higher education, among all of us who have read or are reading for a degree, is the ability to contextualise personal reality, utilising evidence logically and adapting them to theoretical conventions. In this vein, whether we are talking about the environment, social deprivation, government accountability and so on, the process upon which we explore them follows the same conventions of scholarship and investigation. The arguments constructed are evidence based and focused on the subject rather than the feelings we have on each matter.

This is a position, academics contemplate when talking to an academic audience and then must transfer the same position in conversation or when talking to a lay audience. The language may change ever so slightly, and we are mindful of the jargon that we may use but ultimately we represent the case for whatever issue, using the same processes, regardless of the audience.

Academic opinion is not merely an expert opinion, it is a viewpoint, that if done following all academic conventions, should represent factual knowledge, up to date, with a degree of accuracy. This is not a matter of opinion; it is a way of practice. Which makes non-academic rebuttals problematic. The current prevailing approach is to present everything as a matter of opinion, where each position is presented equally, regardless of the preparation, authority or knowledge embedded to each. This balanced social approach has been exasperated with the onset of social media and the way we consume information. The problem is when an academic who presents a theoretical model is confronted with an opinion that lacks knowledge or evidence. The age-old problem of conflating knowledge with information.

This is aggravated when a climatologist is confronted by a climate change denier, a criminologist is faced with a law and order enthusiast (reminiscing the good-old days) or an economist presenting the argument for remain, shouted down by a journalist with little knowledge of finance. We are at an interesting crossroad, after all the facts and figures at our fingertips, it seems the argument goes to whoever shouts the loudest.

Popper K., (1959/2002), The Logic of Scientific Discovery, tr. from the German Routledge, London