Home » Teaching (Page 5)

Category Archives: Teaching

UCU Strike 21-22 January 2022

More information around the University and College University [UCU] and the Four Fights Dispute can be found here.

Information about the Northampton branch of UCU can be found here and here.

You can also find out why striking is a criminological issue here: https://thoughtsfromthecriminologyteam.blog/2021/12/10/striking-is-a-criminological-matter/ and here: https://thoughtsfromthecriminologyteam.blog/2022/02/18/united-nations-un-world-day-of-social-justice/

United Nation’s (UN) World Day of Social Justice

Achieving justice through formal employment

This Sunday 20th February marks the United Nation’s (UN) World Day of Social Justice. The theme this year is ‘achieving justice through formal employment’. The focus is on the informal economy, in which 60% of the world’s employed population participate. Those employed in the informal economy are not protected by regulations such as health and safety or employment rights and are not entitled to employment benefits such as sickness and holiday pay. People who work in the informal economy are much more likely to be poor, in which case housing and unsanitary conditions can compound the impact of working in the informal economy.

When we in the global North talk about the informal economy, there is often an assumption that this occurs in poorer, less developed countries (it is semantics – here in the UK we use the preferred term of the ‘gig economy’). However, this is a global problem and often the richest industries and countries engage in abusive employment practices that form part of the problem of the informal economy. Let’s take Qatar as an example. Qatar has one of the highest GDP per capita in the world, but it also has an extremely high level of income inequality. I heard Natasha Iskandar recently discussing the case of migrant workers in Qatar during construction for the football world cup. Migrant workers are vulnerable to the informal economy due to various labour and visa restrictions throughout the world. In Qatar migrant workers were needed to build the stadia, however this came at a cost to employment conditions including wage theft, forced overtime, debt bondage and intimidation. At the time in Qatar, it was illegal for such workers to withhold labour and they could not voluntarily leave the country without the consent of their employers. The often-abusive employment conditions within the Kafala system of sponsored migrant labour would push people into the informal economy. Having come under some criticism, Qatar has since reformed the Kafala system to improve social protections for migrant workers and were the first of the Gulf countries to do so.

The informalisation of the education economy

On a global scale, the problem of the informal economy is vast there are unique challenges to different groups and social contexts. It will take a large-scale effort to make changes needed to abolish the informal economy globally if it ever can be abolished. Perhaps though we can start by looking a little closer to home and see if we can make a difference there. Academia has traditionally been perceived by those outside of it as a sector of elite institutions, the ‘ivory towers’, where highly paid, highly skilled academics talk from their parapets in a language those outside of it cannot understand. There is a perception that academics are highly paid, highly skilled workers with job security, good pensions, and a comfortable working life. Higher education management in some institutions have been known to refer to academics using derogatory terms such as ‘slackademics’. As every hard-working academic will tell you, this cannot be further from the truth.

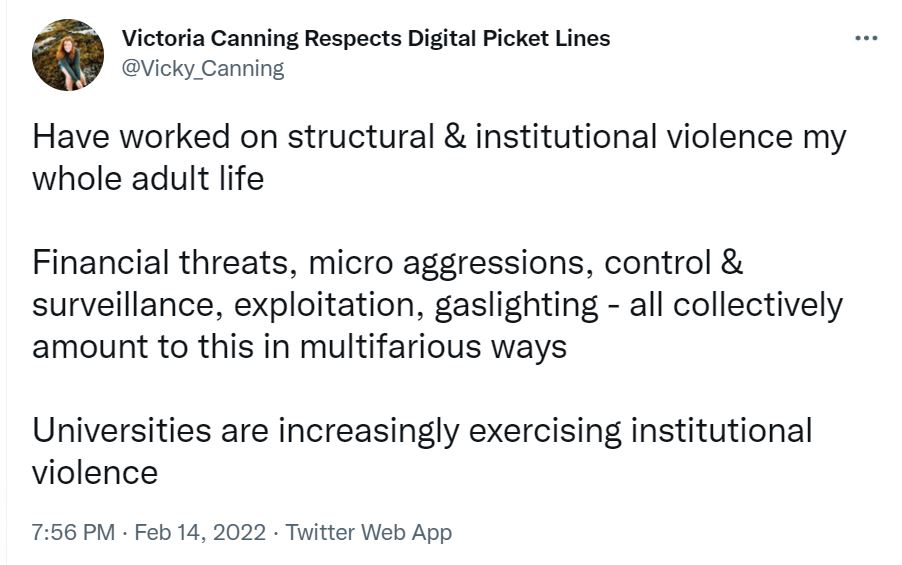

What used to be a place of free thinking, sharing of ideas, and encouraging students to do the same (note: I’m told academics used to have time to think and read) has become a place where profit and business ethos overrides such niceties. The marketisation of education, which can be traced back to the early 1990s has seen a growth in informal employment putting paid to the myths of job security inter alia, lecturing staff well-being. As Vicky Canning put it in the below Tweet, this constitutes institutional violence, something we criminologists are charged with speaking up against.

The university industry has become increasingly reliant on casualised contracts leading to staff not being able to get mortgages or tenancies. During my time at a previous institution, I worked on fixed term contracts as a teaching assistant. The teaching contracts would typically last for 10-12 weeks, there were constant HR errors with contracts, which were often not confirmed until the week before teaching or even after teaching had started. Each semester there would be at least a few teaching assistants who got paid incorrectly or did not get paid at all. These are the people delivering teaching to students paying at least £9,250 per year for their education. Is this value for money? Is this fair? In a previous round of strikes at that institution I let my students know that after all the work they put into writing, I only got paid for 20 minutes to mark one of their 3,500-word essays. They did not seem to think this was value for money.

While I was working under such contracts, I had to move to a new house. I visited many properties and faced a series of affordability checks. As the contracts were short term, landlords would not accept this income as secure, and I was rejected for several properties. I eventually had to ask a friend to be a guarantor but without this, I could easily have ended up homeless and this has happened to other university teaching staff. It was reported recently in the Guardian that a casualised lecturer was living in a tent because she was not able to afford accommodation. All this, on top of stressful, unmanageable workloads. These are the kinds of things casualised university staff must contend with in their lives. These are the humans teaching our students.

This is just one of the problems in the higher education machine. The problems of wage theft, forced overtime, debt bondage and intimidation seen in Qatar are also seen in the institutionally violent higher education economy, albeit to a lesser (or less visible) extent. Let’s talk about wage theft. A number of universities have threatened 100% salary deductions for staff engaging in action short of strike, or in simple terms, working the hours they are contracted to do. Academics throughout the country are being threatened with wage theft if they cannot complete their contractual duties within the hours they are paid for. Essentially then, some higher education establishments are coercing staff to undertake unpaid overtime, not dissimilar to the forced overtime faced by exploited migrant workers building stadia in Qatar.

Academics across the country need to see change in these academic workloads so we can research the exploitation of migrants in the informal labour market, to work towards UN sustainability goals to help address the informal economy, to engage in social justice projects within the informal economy in our local area, and to think about how we can engage our students in such projects. In effect academics need to work in an environment where they can be academics.

How can we begin to be critical of or help address global issues such as the informal economy when our education system is engaging in questionable employment practices, the kind of which drive people into the informal economy, the kind of employment practices that border the informal economy. Perhaps higher education needs to look inwards before looking out

If we could empathize with all life, we… [fill in the blank]

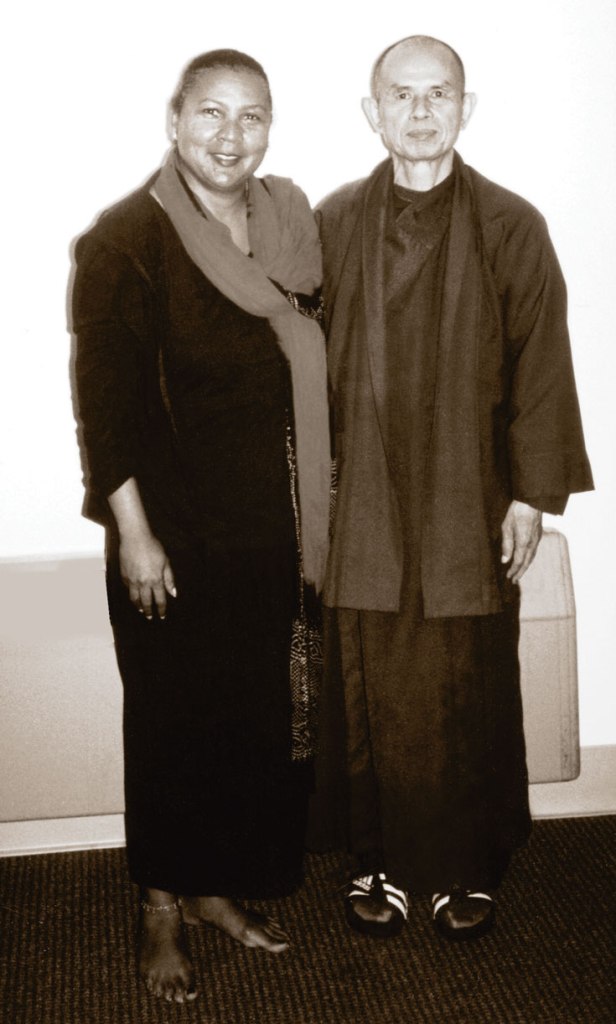

In Honour of my two teachers’ passing (seen together here). Rest In Power, bell hooks (d. 15/12/21) and Thich Nhat Hanh (d. 22/01/22).

If we could empathize with all life, we…

… wouldn’t treat all animals as either food or fodder.

… wouldn’t develop nuclear technology into bombs.

…would never show an interest in making so many guns and ways of destroying life.

…would more genuinely aim to achieve mutual understanding between individuals.

…wouldn’t have so much intergenerational trauma within families, communities, nations.

…would be more neighborly in all our affairs.

…wouldn’t treat trade like a sport, a winner-takes-all competition over natural resources.

…would harness the power of the sun for it shines on all life collectively.

…would cultivate care, and be kinder as a general rule.

… would teach kindness in school, a required class on every campus.

…would not build entire ideologies, systems of government, religions, arts, and culture around patriarchy.

… would not be reduced to binaries, not just in gender, but ‘black or white’ in our overall thinking, because that’s where it came from: A false yet powerful and enduring dichotomy.

Binary thinking produced gender binaries, not the other way around. Knowing this is key to its undoing. Please know that capitalism produced racism, and greed crafted classism. A2 + B2 = C2, still. Racism is exponentially untamed greed; and patriarchy an inferiority complex run rampant and amok. Such cultures of greed can’t be conquered by competition; greed can’t be beat! We need a new dimension.

If we could empathize with all life, we would aspire to be far more fair.

If we could empathize with all life, we would love more.

Your turn.

Fill in the blank.

Poetry on prisons

Recently in CRI3001 Crime and Punishment we’ve been exploring prison poetry drawn from the volumes published by the fantastic Koestler Arts (some examples and inspiration can be found here). Students were inspired by this to write their own poems on prison and you will find some excellent examples below.

Moonlight

I sing to all of the spiders on the wall

They comfort me from my fear of the unknown

All the sounds outside as I lay here petrified

Of the consequences that lay aheadTime is far behind my state of mind

Noran

Deprived myself of the will to fight

For peaceful nights

Moving on

Longing for the past,

Wanting to go back,

To change our future.

Living with regret,

Feeling sorry for hurting you,

Living in isolation,

Needing to hear from you.

Wondering if you’re doing well,

Do you remember me?

Are you moving on?

Do you like it?

Living on the outside?

Outside of these four walls.

These grey walls entrap me,

Every day I feel smaller.

Unimportant. I’m suffocating.

I hope the world hasn’t changed.

I hope everything stays the same.

So that one day, maybe

I could come back to you

Danique

Trapped,

Between four walls for life.

Non-existent,

I am but a shadow of my past self.

Detached,

No amount of WIFI can ever reconnect what was lost.

A

Prisoner’s Perspective

Prison is an escape, prison is a relief, prison is warm, prison is secure. Prison is easier than the cold, sleepless, torrid nights. Prison is not a punishment. Prison is a consolation.

Prison is lonely, prison is isolated. Prison does not help; it does not rehabilitate. Prison stops the time. Prison fails us.

Prison is opportunistic, prison allows me to be a leader, prison allows people to live in fear of me. Something I never was in the outside world.

Prison isn’t a one fits all, prison is individualised offender to offender. Does prison work? Is Prison effective? Is prison the way forward?

Saiya

I Created This

Pulled up and stopped

Big iron gates spiked with fear and dread

he shouts “Clear” and gates open

with rumbling vibration

Why does this feel like the beginning of the end

Queueing quietly waiting turn for changing clothing

Wishing the view was slightly different

This is my home, the world is now distant

Showers cold and beds so hard

Waiting for the order from the guards

“Dinner served” I hear them shout

Hoping it’s not just bland

Thinking about roast dinners

This is my life, I created this

Given the chance, time and again,

But now this is my life, I created this

SKM

Poetry and other forms of literature offer the opportunity to explore criminological issues in a different medium. They allow for ideas to develop in a more natural way than academic conventions usually allow. As you can see from the poems above, our students rose to the challenge and embraced the opportunity to think differently about Criminology.

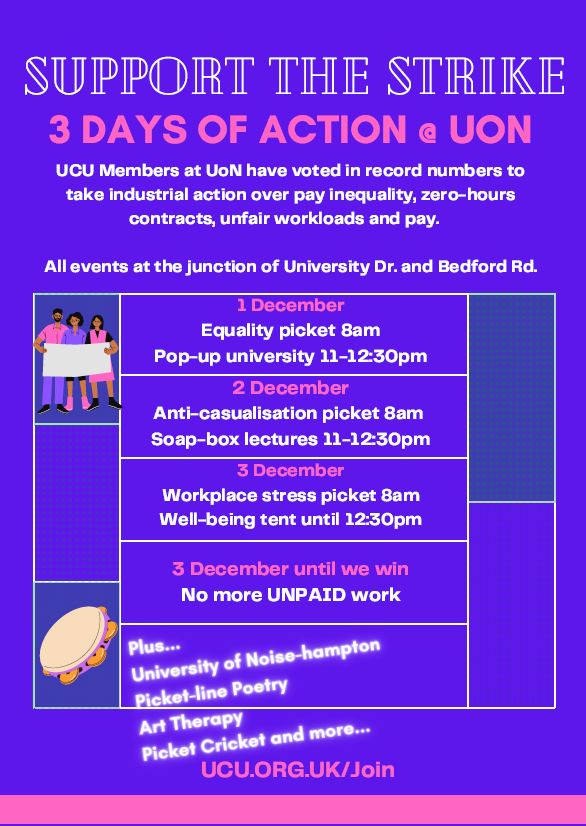

Striking is a criminological matter

You may have noticed that the University and College Union [UCU] recently voted for industrial action. A strike was called from 1-3 December, to be followed by Action Short of a Strike [ASOS], in essence a call for university workers to down tools for 3 days, followed by a strict working to contract. For many outside of academia, it is surprising to find how many hours academics actually work. People often assume that the only work undertaken by academics is in the classroom and that they spend great chunks of the year, when students are on breaks, doing very little. This is far from the lived experience, academics undertake a wide range of activities, including reading, writing, researching, preparing for classes, supervising dissertation students, attending meetings, answering emails (to name but a few) and of course, teaching.

UCU’s industrial action is focused on the “Four Fights“: Pay, Workload, Equality and Casualisation and this campaign holds a special place in many academic hearts. The campaign is not just about improving conditions for academics but also for students and perhaps more importantly, those who follow us all in the future. What kind of academia will we leave in our wake? Will we have done our best to ensure that academia is a safe and welcoming space for all who want to occupy it?

In Criminology we spend a great deal of time imagining what a society based on fairness, equity and social justice might look like. We read, we study, we research, we think, and we write about inequality, racism, misogyny, disablism, homophobia, Islamophobia and all of the other blights evident in our society. We know that these cause harm to individuals, families, communities and our society, impacting on every aspect of living and well-being. We consider the roles of individuals, institutions and government in perpetuating inequality and disadvantage. As a theoretical discipline, this runs the risk of viewing the world in abstract terms, distancing ourselves from what is going on around us. Thus it is really important to bring our theoretical perspectives to bear on real world problems. After all there would be little point in studying criminology, if it is only to see what has happened in the past.

Criminology is a critique, a question not only of what is but might be, what could be, what ought to be. Individuals’ behaviours, motivations and reactions and institutional and societal responses and actions, combine to provide a holistic overview of crime from all perspectives. It involves passion and an intense desire to make the world a little better. Therefore it follows that striking must be a criminological matter. It would be crass hypocrisy to teach social justice, whilst not also striving to achieve such in our professional and personal lives. History tells us that when people stand up for themselves and others, their rights and their future, things can change, things can improve. It might be annoying or inconvenient to be impacted by industrial action, it certainly is chilly on the picket line in December, but in the grand scheme of things, this is a short period of time and holds the promise of better times to come.

Meet the Team: Stephanie Richards, Associate Lecturer in Criminology

A Warm Welcome

Hello all! I would like to introduce myself. My name is Stephanie Richards and I am your Student Success Mentor (SSM). Some of the criminology and criminal justice students would have already had the opportunity to meet me, as I was their Student Success Mentor previously. So, it will be great to touch base with you all and it would also be great for the new cohorts to say hi when you see me on campus.

It is that time of the year when we see new students and our existing students getting ready to tackle the trials of higher education. Being a SSM I am fully aware of the challenges that you will face, and I am here to support you throughout your time at UON. As a previous student I can testify that studying at university is incredibly challenging. The leap from school/ college can be daunting at first. A new building that seems like a maze or the idea of being surrounded by strangers that you probably think you have nothing in common with can be enough to encourage you to run for the hills….stepping into a workshop for the first time can give you a stomach flip, but once you take that first seat in class you will come to realise it does get easier.

Upon reflection of my experience as a new undergraduate student I would have to be honest and express the difficulties that I suffered adjusting to my new way of life. I could not keep my head above the masses of reading, and when I did manage to get some of the seminar prep completed, most of the time I struggled with the new questions and concepts that were posed to me. This will be the experience of most, if not all the new students starting out on their university education. This is part of the complex journey of academia. My advice would be to pace yourself, time management is key, if you struggle to understand the work that has been set, ask for clarity and develop positive relationships with your peers and the staff at UON…………..being part of a strong community will get you through a lot!

My role is not just about assisting the new students that have started their university journey, I am also here to help UONs existing students. Getting back into the swing of studying can be daunting after the summer break. Adjusting to face-to-face education can be an overwhelming process but one that should be embraced. We will all miss our pyjama bottoms and slippers but being back on campus and getting some normality back in your day is worth the sacrifice.

The team of SSM’s are here to support you throughout your journey so please get in touch if you require our assistance. We never want you to feel alone in this journey and we want to assist you the best ways we can. We want you to progress and meet your full learning potential, and to get the most out of your university experience.

Meet the Team: Francine Bitalo, Associate Lecturer in Criminology

Hi everyone! My name is Francine Bitalo and I will be your new Student Success Mentor for this year. I am looking forward to meeting and assisting you all in your academic journey. Feel free to contact me for any support.

Being a graduate from the University of Northampton I can relate to you all, I know how challenging student life can be especially when dealing with other external factors. You may go through stages where you doubt your creativity, abilities and maybe even doubt whether the student life is for you. When I look back at when I was a student, I definitely regret not contacting the Student Success Mentors that were available to me or simply utilising more of the university’s support system. It is important for you seek support people like myself are here to help and recommend you to the right people.

Besides everything, Criminology is such an interesting course to study if you are anything like me by the end of it all you won’t view the world the same. Many of you have probably already formed your views on life especially when it comes to understanding crime. Well by the end of it all your ways of viewing the world will enhance and become more complex, theoretical and constructive. The advice I give you all is to enjoy the journey, be open minded and most importantly prepare for exciting debates and conversations.

Look forward to meeting you all.

Prison education: why it matters?

Five year ago, Dame Sally Coates released an independent report on prison education. Recently the Chief Inspector for Ofsted, Amanda Spielman and The HM Inspectorate of Prisons, Charlie Taylor, made a joint statement reflecting on that report. Their reflections are critical on the lack of implementation of the original report, but also of the difficulties of managing education in prison especially at a time of a global pandemic. The lack of developing meaningful educational provision and delivering remote teaching led to many prisoners without sufficient opportunity to engage with learning.

In a situation of crisis such as the global pandemic one must wonder if this is an issue that can be left to one side for now, to be reviewed at a later stage. At the University of Northampton, as an educational institution we are passionate about learning opportunities for all including those incarcerated. We have already developed an educational partnership with a local prison, and we are committed to offer Higher Education to prisoners. Apart from the educational, I would add that there is a profound criminological approach to this issue. Firstly, I would like to separate what Dame Coates refers to as education, which is focused on the basic skills and training as opposed to a university’s mandate for education designed to explore more advanced ideas.

The main point to both however is the necessity for education for those incarcerated and why it should be offered or not. In everyday conversations, people accept that “bad” people go to prison. They have done something so horrible that it has crossed the custody threshold and therefore, society sends them to jail. This is not a simple game of Monopoly, but an entire criminal justice process that explores evidence and decides to take away their freedom. This is the highest punishment our society can bestow on a person found guilty of serious crimes. For many people this is appropriate and the punishment a fitting end to criminality. In criminology however we recognise that criminality is socially constructed and those who end up in prisons may be only but a specific section of those deemed “deviant” in our society. The combination of wrongdoing and socioeconomic situations dictate if a person is more or less likely to go to prison. This indicates that prison is not a punishment for all bad people, but some. Dame Coates for example recognises the overrepresentation of particular ethnic minorities in the prison system.

This raises the first criminological issue regarding education, and it relates to fairness and access to education. We sometimes tend to forget that education is not a privilege but a fundamental human right. Sometimes people forget that we live in a society that requires a level of educational sophistication that people with below basic levels of literacy and numeracy will struggle. From online applications to job hunting or even banking, the internet has become an environment that has no place for the illiterate. Consider those who have been in prison since the late 1990s and were released in the late 2010s. People who entered the prison before the advancement of e-commerce and smart phones suddenly released to a world that feels like it is out of a sci-fi movie.

The second criminological issue is to give all people, regardless of their crimes, the opportunity to change. The opportunity of people to change, is always incumbent on their ability to change which in turn is dependent on their circumstances. Education, among other things, requires the commitment of the learner to engage with the learning process. For those in prison, education can offer an opportunity to gain some insight that their environment or personal circumstances have denied them.

The final criminological issue is the prison itself. What do we want people to do in them? If prison is to become a human storage facility, then it will do nothing more than to pause a person’s life until they are to be released. When they come out the process of decarceration is long and difficult. People struggle to cope and the return to prison becomes a process known as “revolving doors”. This prison system helps no one and does nothing to resolve criminality. A prison that attempts to help the prisoners by offering them the tools to learn, helps with the process of deinstitutionalisation. The prisoner is informed and aware of the society they are to re-join and prepares accordingly. This is something that should work in theory, but we are nowhere there yet. If anything, it is far from it, as read in Spielman and Taylor’s recent commentary. Their observations identify poor quality education that is delivered in unacceptable conditions. This is the crux of the matter, the institution is not really delivering what it claims that is does. The side-effect of such as approach is the missed opportunity to use the institution as a place of reform and change.

Of course, in criminological discourse the focus is on an abolitionist agenda that sees beyond the institution to a society less punitive that offers opportunities to all its citizens without discrimination or prejudice. This is perhaps a different topic of conversation. At this stage, one thing is for sure; education may not rehabilitate but it can allow people to self-improve and that is a process that needs to be embraced.

References

Coates, S. (2016), Unlocking Potential: A review of education in prisons, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/unlocking-potential-a-review-of-education-in-prison

Spielman, A. and Taylor, C. (2021), Launching our Prison Education Review, https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/launching-our-prison-education-review

Originally published here