Home » Structural Violence

Category Archives: Structural Violence

Is it time to unleash your criminological imagination?

In this blog entry, I am going to introduce a seemingly disconnected set of ideas. I say seemingly, because at the end, all will hopefully make sense. I suspect the following also demonstrates the often chaotic and convoluted process of my thought processes.

I’ve written many times before about Criminology, at times questioning whether I have any claim to the title criminologist and more recently, what those with the title should talk about. These come on top of hundreds of hours of study, contemplation and reflection which provides the backdrop for why I keep questioning the discipline and my place within it. I know one of the biggest issues for me is social sciences, like Criminology and many others, love to categorise people in lots of different ways: class, race, gender, offender, survivor, victim and so on. But people, including me, don’t like to be put in boxes, we’re complex animals and as I always tell students, people are bloody awkward, including ourselves! There is also a far more challenging issue of being part of a discipline which has the potential to cause, rather than reduce or remove harm, another topic I’ve blogged on before.

It’s no secret that universities across the UK and further afield are facing many serious, seemingly intractable challenges. In the UK these range from financial pressures (both institutional and individual), austerity measures, the seemingly unstoppable rise of technology and the implicit (or explicit, depending on standpoint) message of Brexit, that the country is closed to outsiders. Each of the challenges mentioned above seem to me to be anti-education, rather than designed to expand and share knowledge, they close down essential dialogue. Many years ago, a student studying in the UK from mainland Europe on the Erasmus scheme, said to me that our facilities were wonderful, and they were amazed by the readily available access to IT, both far superior to what was available to them in their own country. Gratifying to hear, but what came next was far more profound, they said that all a serious student really need is books, a enthusiastic and knowledgeable teacher and a tree to sit under. Whilst the tree to sit under might not work in the UK with our unpredictable weather, the rest struck a chord.

The world seems in chaos and war-mongers everywhere are clamouring for violence. Recent events in Darfur, Palestine, Sudan, Ukraine, Venezuela and many other parts of the world, demonstrate the frailty, or even, fallacy of international law, something Drs @manosdaskalou, @paulsquaredd and @aysheaobrien1ca0bcf715 have all eloquently blogged about. But while these discussions are important and pertinent, they cannot address the immediate harm caused to individuals and populations facing these many, varied forms of violence. Furthermore, whilst it’s been over 80 years since Raphäel Lemkin first coined the term ‘genocide’, it seems world leaders are content to debate whether this situation or that situation fits the definition. But, surely these discussions should be secondary, a humanitarian response is far more urgent. After all, (one would hope) that the police would not standby watching as one person killed another, all whilst having a discussion around the definition of murder and whether it applied in this context.

The rise of technology, in particular Generative Artificial Intelligence, has been the focus of blogs from Drs @sallekmusa, @5teveh and myself, each with their own perspective and standpoint. Efforts to combat the harmful effects of Grok enabling the creation of non-consensual pornographic images demonstrate both new forms of Violence Against Women and Girls [VAWG] and the limitations of control and enforcement. Whilst countries are rushing to ban Grok and control the access of social media for children under 16, it is clear that Grok and X are just one form of GAI and social media, there is seemingly nothing to stop others taking their place. And as everyone is well aware, laws are broken on a daily basis (just look at the court backlog and the overflowing prisons) and with no apparent way of controlling children’s access to technology (something which is actively encouraged in schools, colleges and universities) these attempts seem doomed to fail. Maybe more regulation. more legislation isn’t the answer to this problem.

Above I have briefly discussed four seemingly intractable problems. In each arena, we have many thousands of people across the globe trying to solve the issues, but the problems still remain. Perhaps we should ask ourselves the following questions:

- Maybe we are asking the wrong people to come up with the answers?

- Maybe we are constraining discussions and closing down debate?

- Maybe by allowing the established and the powerful to control the narrative we just continue to recycle the same problems and the same hackneyed solutions?

What if there’s another way?

And here we come to the crux of this blog, in Criminology we are challenged to explore any problem from all perspectives, we are continually encouraged to imagine a different world, what ought or could be a better place for all. I have the privilege of running two modules, one at level 4 Imagining Crime and one at Level 6 Violence. In both of these students work together to see the world differently, to imagine a world without violence, a world in which justice is a constant and reflection a continual practice. Walking into one of these classrooms you may well be surprised to see how thoughtful and passionate people can be when faced with a seemingly unsolvable problem when everything on the table is up for discussion. Although often misattributed to Einstein, the statement ‘Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results’ seems apposite. If we want the world to be different, we have to allow people to think about things differently, in free and safe spaces, so they can consider all perspectives, and that is where Criminology comes in.

Be fearless and unleash your criminological imagination, who knows where it might take you!

The Caracas Job: International Law and Geo-Political Smash and Grab

So, they actually did it, eh?

It’s January 2026, and I, for one, am still trying to remember my work logins and wondering if this is the year that Aliens invade Earth. Yet, across the pond, the Americans have decided to kick off the New Year with a throwback classic: decapitating a sovereign Latin-American government.

Adiós Maduro. We hardly know yer pal. Well, we all knew you enough to know you were a disastrous authoritarian kleptocrat who managed to bankrupt a country sitting on a lake of oil. But we need to talk about how it happened, because if you listen carefully enough to the wind wuthering through the empty corridors of the UN Building in New York, you can probably hear the death rattle of what I once studied and was quaintly entitled, ‘Rules-Based International Order’-aka International Law.

As one colleague and our very own Dr Manos Daskolou pointed out to me this very day, it’s almost eighty years since 1945. Eight decades of pretending we built a civilised global architecture out of the ashes of World War II. We built tribunals in The Hague, we wrote very sternly worded Geneva Conventions, and we created a Security Council where superpowers could veto each other into paralysis. It was a lovely piece of Geo-Political theatre.

The days-old removal of the Venezuelan head of state by direct US intervention isn’t just a deviation from the norm: it’s a flagrant breach of the foundational prohibition on the ‘use of force’ found in Article 2(4) of The UN Charter. The mask has slipped, and underneath it is just raw, naked power.

As a Brit observing this rigmarole from the very cold and soggy sidelines, it’s hard not to view this from a very specific lens. We invented modern imperialism, after all. Criminologists will often discuss concepts like State Crimes. They will often question who indeed polices the Police?

If I decide to kick down my neighbour’s door because I don’t like the way she runs her household, steal her assets and install her sister as the new head of the family, I’m going to court. I am a burglar, a thug and a violent criminal. If a superpower does the same thing to a sovereign nation, they get a press conference at Mar-a-Lago.

For eighty years, the West has been incredibly successful at labelling its own interventions as ‘police actions’ or ‘humanitarian missions’, all the while labelling acts of rivals as ‘aggression’. The Caracas job is the ultimate expression of this.

Listen to the rhetoric coming out of Washington right now. It’s textbook gaslighting. ‘Maduro was a tyrant’, ‘Other countries do worse’, i.e condemning the condemners. They certainly are not arguing that entry into Caracas was legal under the UN Charter was legal because it most definitely wasn’t. They are arguing that the law should not apply to them because their intentions were pure.

Deja Vu-Iraq

The darkest irony of the Venezuelan decapitation is the crushing sense of deja vu. We cannot talk about removing a dictator in the 2020s without flashbacks to Saddam Hussein and Dr David Kelly entering the scene. The parallels are screaming at us. In 2003, the justification for taking Saddam (and, sadly, Dr Kelly as a direct result) out was a cocktail of WMD lies and dangerous rhetoric. As the Chilcot Report stated years ago, the legal basis for military action against Iraq was ‘far from satisfactory’.

The critical failure in Iraq and the one we are doomed to repeat in Venezuela is that it is terrifyingly easy for a superpower like the USA to smash a second-rate military. The hard part is what on earth comes next?

Perhaps it would have been better for the superpowers to manipulate Maduro’s own people, taking him out, so to speak. Organic change in any situation lends legitimacy that enforced or imported change never does. When you decapitate a state at 30,000 feet, you create a vacuum. The USA may have created a dependency, effectively violating the principle of self-determination, which is enshrined in the Human Rights Convention.

The Iranian Elephant In The Room

Of course, none of this is actually happening in a vacuum. Being a Yorkshire lass with Middle Eastern Heritage, I am keenly aware of the politics of the regions hitting the headlines on an almost daily basis. Yet, no one has to have bloodline ties to any of the countries or regions involved to see the obvious Elephant in the room. It’s that flipping obvious. Maduro wasn’t just an irritant because of his economy-crashing style. It was a strategic flipping of the bird for America’s rivals-Crucially, Iran. This is where the narrative gets even darker. This is gang warfare.

The danger here is escalation. If Tehran decides that the fall of Maduro constitutes a direct challenge to its own deterrence strategy, it will not retaliate in the Caribbean. They are likely (if history has taught us anything) to retaliate in the Strait of Hormuz. The butterfly effect of a regime change in Caracas could easily result in the closure of the Suez Canal. Yes, that old chestnut.

The old guard loved International Law. They loved it because they knew how to manipulate it. They used the UN Council like a skilled Barrister uses a loophole. They built coalitions. The current approach-Let’s call it ‘Act Now Think Later Diplomacy’ dispenses with the formalities and paperwork. It sees International Law NOT as a tool to be manipulated, but as an annoying restraint to be ignored. It confirms the narrative that the Nuremberg trials were merely ‘Victors’ Justice’, a system where legal accountability is the privilege of the defeated.

The difference between Putin invading Ukraine and the USA decapitating Venezuela is rapidly becoming a distinction without a difference.

So, here we go in 2026. The powerful have shown they don’t give a toss about the rules. They’ve shown that ‘sovereignty’ is just a word they use in speeches, not really a word they respect.

When people stop believing in the legitimacy of the law, they usually stop following it. We are about to see what happens when the entire world stops believing in the legitimacy of International Law.

It is going to be a messy few decades. Cheers, mine’s a double.

Same shit, different day

I’ve thought long and hard about whether or not to write this blog, it contains nothing new, it adds nothing to the discussion and it is borne of frustration, not just mine. Nevertheless, if the same thing keeps happening, then why not keep shouting about it, even if no-one appears to be listening.

Recently I attended an event supposedly focused on Violence Against Women & Girls [VAWG], the organisers, the venue, the speakers remain anonymous, because this is not about specific individuals or organisations. Instead, as the title indicates, the issues raised below are repeated again and again, across different times and place, involving different people, with different claims to knowledge. Nevertheless, they have far more in common than they would care to acknowledge.

In September 2024, the government announced a commitment to halving VAWG over the next decade. The announcement itself was rather confused, seemingly conflating the term VAWG with Domestic Abuse [DA] whilst simultaneously promising to ‘take back our streets’. The latter horribly reminiscent of the far right’s racists diatribe around taking back our country. But I digress, in the government statement there is no mention of sexual violence, despite Rape Crisis England and Wales’ assertion that 1 in 4 women and girls over 16 have been subjected to sexual assault or rape. Similarly, Refuge suggest that 1 in 4 women will be subjected to forms of domestic abuse across their lifetimes. The statistical data is shaky, the problems with reporting are well documented, but ask any woman, and they will tell you about their own experiences and those of friends and families. A brief glance at the Everyday Sexism Project or Everyone’s Invited will give you some idea of the scale of the violences facing women and girls.

But to return to the latest VAWG event, there have been very many of these, all following the same pattern. Crowds of women in the audience, all experts, some professional, some academic, some through victimisation, some through vicarious victimisation and of course, some of those women encapsulate more than one of those categories, they are not mutually exclusive. So how do we harness and utilise this great body of knowledge, experience and expertise? The sad answer for events like this, is 99% of the time, we don’t. They’re there to sit quietly and listen to the same old narrative from police leaders and officers, saying that the institution has got it wrong in the past, but has learnt lessons and is now doing much better. Noticeably, there are few men in the audience, only those compelled to attend by their employment, after all VAWG explicitly mentions women and girls so it must be a female problem, despite the fact that the violences are predominately carried out by men.

To really drive the message home, we have speakers who can’t be bothered to prepare an accessible presentation for their audience. Relying instead on their white privilege, their charisma and charm (think a poor parody of a 1990’s Hugh Grant in a Richard Curtis film), with their funny little anecdotes of how they met a woman who changed their view on VAWG. Or how primary school teachers are usually women, and that’s where the problems begin, they just don’t do enough to support our little boys and young men on their journeys. Similarly, mothers who don’t pay enough attention which mean their sons go onto to become these violent men. We have white women too, ones that want the audience to focus on women who have been killed by men, but who cannot actually be bothered to find out how to say their names, stumbling over any name that is not anglicised.

In the audience it is notable that there are few Black and Brown women present. Even when they are invited as speakers, they are cut short, talked over, their names forgotten or mispronounced. They are the add-ons, a pathetic attempt at inclusivity, but don’t worry they’re never the main attraction. That spotlight is always reserved for men. No wonder Black and Brown women can’t face attending, or leave part way through, they’re sick and tired of being patronised while they pick up the broken pieces of men’s violences.

So what do women actually learn from these events? They learn to keep quiet, to pretend they’re learning something, but in the breaks they get together and talk about their frustrations, their ongoing exclusion from discussions. They learn that the problem belongs to them. That not only have they got to mop up women’s blood, sweat and tears, using plenty of their own in the process, to support and rebuild women after trauma, they are also responsible for the boys and men.

It really does not have to be this way! In every community there are women of all colours, all religions, all sexualities, all nations, doing the hard work. Building each other up against a maelstrom of never ending male violence, not to mention the additional violences of racism, microaggressions and exclusion. These are the experts, these are the people with whom the solutions lie. The police have had almost 200 years to get it right, they are nowhere near, time for them to move over and let the real experts do the talking, whilst they listen and start to hear and learn!

LET THEM EAT SOUP

Introduction

What is a can of soup? If you ask a market expert, it is a high-profit item currently pushing £2.30 (branded) in some UK shops[i]. If you ask a historian[ii], it is the very bedrock of organised charity-the cheapest, easiest way to feed a penniless and hungry crowd.

The high price of something so basic, like a £2.30 can of soup, is a massive conundrum when you remember that soup’s main historical job was feeding poor people for almost nothing. Soup, whose name comes from the old word Suppa[iii](meaning broth poured over bread), was chosen by charities because it was cheap, could be made in huge pots, and best of all could be ‘stretched’ with water to feed even more people on a budget[iv].

In 2025, the whole situation is upside down. The price of this simple food has jumped because of “massive economic problems and big company greed[v]. At the same time, the need for charity has exploded with food bank use soaring by an unbelievable 51% compared to 2019[vi]. When basic food is expensive and charity is overwhelmed, it means our country’s safety net is broken.

For those of us who grew up in the chilly North, soup is more than a commodity: it is a core memory. I recall winter afternoons in Yorkshire, scraping frost off the window, knowing a massive pot of soup was bubbling away. Thick, hot and utterly cheap. Our famous carrot and swede soup cost pennies to make, tasted like salvation and could genuinely “fix you.” The modern £2.30 price tag on a can feels like a joke played on that memory, a reminder that the simplest warmth is now reserved for those who can afford the premium.

This piece breaks down some of the reasons why a can of soup costs so much, explores the 250-year-old long, often embarrassing history of soup charity in Britain and shows how the two things-high prices and huge charity demand-feed into a frustrating cycle of managed hunger.

Why Soup Costs £2.30

The UK loves its canned soup: it is a huge business worth hundreds of millions of pounds every year[vii], but despite being a stable market, prices have been battered by outside events.

Remember that huge cost of living squeeze? Food inflation prices peaked at 19.1% in 2023, the biggest rise in 40 years[viii]. Even though things have calmed down slightly, food prices jumped again to 5.1% in August 2025, remaining substantially elevated compared to the overall inflation rate of 3.8% in the same month[ix]. This huge price jump hits basic stuff the hardest, which means that poor people get hurt the most.

Why the drama? A mix of global chaos (like the Ukraine conflict messing up vegetable oil and fertiliser supplies) and local headaches (like the extra costs from Brexit) have made everything more expensive to produce[x].

Here’s the Kicker: Soup ingredients themselves are super cheap. You can make a big pot of vegetable soup at home for about 66p a serving, but a can of the same stuff? £2.30. Even professional caterers can buy bulk powdered soup mix for just 39p per portion[xi].

The biggest chunk of that price has nothing to do with the actual carrots and stock. It’s all the “extras”. You must pay for- the metal can, the flashy label and the marketing team that tries to convince you this soup is a “cosy hug”, and, most importantly everyone’s cut along the way.

Big supermarkets and shops are the main culprits. They need a massive 30-50% profit margin on that can for just putting it on the shelf[xii]. Because people have to buy food to live (you can’t just skip dinner) big companies can grab massive profits, turning something that you desperately need into something that just makes them rich.

This creates the ultimate cruel irony. Historically, soup was accessible because it was simple and cheap. Now, the people who are too busy, too tired or too broke to cook from scratch-the working poor are forced to buy the ready-made cans[xiii]. They end up paying the maximum premium for the convenience they need most, simply because they don’t have the time or space to do it the cheaper way.

How Charity Got Organised

The idea of soup as charity is ancient, but the dedicated “soup kitchen” really took off in late 18th century Britain[xiv].

The biggest reasons were the chaos after the Napoleonic wars and the rise of crowded industrial towns, which meant that lots of people had no money if their work dried up. By 1900 England had gone from a handful of soup kitchens to thousands of them[xv].

The first true soup charity in England was likely La Soupe, started by Huguenot refugees in London in the late 17th Century[xvi]. They served beef soup daily-a real community effort before the phrase “soup kitchen” was even popular.

Soup was chosen as the main charitable weapon because it was incredibly practical. It was cheap, healthy and could be made in enormous quantities. Its real superpower was that it could be “stretched” by adding more water allowing charities to serve huge numbers of people for minimum cost[xvii].

These kitchens were not just about food; they were tools for managing poor people. During the “long nineteenth century” they often fed up to 30% of a local town’s population in winter[xviii]. This aid ran alongside the stern rules of the Old Poor Laws which sorted people into “deserving” (the sick or old) and the ‘undeserving’ (those considered lazy).

The queues, the rules, and the interviews at soup kitchens were a kind of “charity performance” a public way of showing who was giving and who was receiving, all designed to reinforce class differences and tell people how to behave.

The Stigma and Shame of Taking The Soup

Getting a free bowl of soup has always come with a huge dose of shame. It’s basically a public way of telling you “We are the helpful rich people and you are the unfortunate hungry one” Even pictures in old newspapers were designed to make the donors look amazing whilst poor recipients were closely watched[xix].

Early British journalists like Bart Kennedy used to moan about the long, cold queues and how staff would ask “degrading questions” just before you got your soup[xx]. Basically, you had to pass a misery test to get a bowl of watery vegetables, As one 19th Century writer noted, the typical soup house was rarely cleaned, meaning the “aroma of old meals lingers in corners…when the steam from the freshly cooked vegetables brings them back to life”[xxi].

For the recipient, the act of accepting aid became a profound assault on their humanity. The writer George Orwell, captured this degradation starkly, suggesting that a man enduring prolonged hunger “is not a man any longer, only a belly with a few accessory organs”[xxii]. That is the tragic joke here, you are reduced to a stomach that must beg.

By the late 19th Century, people started criticising soup kitchens arguing that they “were blamed for creating the problem they sought to alleviate”[xxiii]. The core problem remains today: giving someone a temporary food handout is just a “band-aid” solution that treats the symptom but ignores the real disease i.e. not enough money to live on.

This critique was affirmed during the Great Depression in Britain, when mobile soup kitchens and dispersal centres became a feature of the British urban landscape[xxiv]. The historical lesson is clear: private charity simply cannot solve a national economic disaster.

The ultimate failure of the system as the historian A.J.P. Taylor pointed out is that the poor demanded dignity. “Soup kitchens were the prelude to revolution, The revolutionaries might talk about socialism, those who actually revolted wanted ‘the right to work’-more capitalism, not it’s abolition[xxv]” They wanted a stable job, not perpetual charity.

Expensive Soup Feeds The Food Bank

The UK poverty crisis means that 7.5 million people (11% of the population) were in homes that did not have enough food in 2023/24[xxvi]. The Trussell Trust alone gave out 2.9 million emergency food parcels in 2024/2025[xxvii]. Crucially, poverty has crept deeper into the workforce: research indicates that three in every ten people referred to in foodbanks in 2024 were from working households[xxviii]. They have jobs but still can’t afford the supermarket prices.

The charities themselves are struggling, hit by a “triple whammy” of rising running costs (energy, rent) and fewer donations[xxix]. This means that many charities have had to cut back, sometimes only giving out three days food instead of a week[xxx]. The safety net in other words is full of holes.

The necessity of navigating poverty systems just to buy food makes people feel trapped and hopeless which is a terrible way to run a country[xxxi].

Modern food banks are still stuck in the old ways of the ‘deserving poor.’ They usually make you get a formal referral—a special voucher—from a professional like a doctor, a Jobcentre person, or the Citizens Advice bureau[xxxii].It’s like getting permission from three different people to have a can of soup.

Charity leaders know this system is broken. The Chief Executive of the Trussell Trust has openly said that food banks are “not the answer” and are just a “fraying sticking plaster[xxxiii].” The system forces a perpetual debate between temporary relief and systemic reform[xxxiv]. The huge growth of private charity, critics argue, just gives the government an excuse to cut back on welfare, pretending that kind volunteers can fix the problem for them[xxxv].

The final, bitter joke links the expensive soup back to the charity meant to fix the cost. Big food companies use inflation to jack up prices and boost profits. Then, they look good by donating their excess stock—often the highly processed, high-profit stuff—to food banks.

This relationship is called the “hunger industrial complex”[xxxvi]. The high-margin, heavily processed canned soup—the quintessential symbol of modern pricing failure—often becomes a core component of the charitable food parcel. The high price charged for the commodity effectively pays for the charity that manages the damage the high price caused[xxxvii]. You could almost call it “Soup-er cyclical capitalism.”

Conclusion

The journey from the 18th-century charitable pot to the 21st-century £2.30 can of soup shows a deep failure in our society. Soup, the hero of cheap hunger relief, has become too pricey for the people who need it most. This cost is driven by profit, not ingredients.

This pricing failure traps poor people in expensive choices, forcing them toward overwhelmed charities. The modern food bank, like the old soup kitchen, acts as a temporary fix that excuses the government from fixing the root cause: low income. As social justice campaigner Bryan Stevenson suggests, “Poverty is the parent of revolution and crime”[xxxviii]. No amount of £2.30 soup can mask the fact that hunger is fundamentally an issue of “justice,” not merely “charity”.

Fixing this means shifting focus entirely. We must stop just managing hunger with charity[xxxix] and instead eliminate the need for charity by making sure everyone has enough money to live and buy their own food. This requires serious changes: regulating the greedy markups on basic food and building a robust state safety net that guarantees a decent income[xl]. The price of the £2.30 can is not just inflation: it’s a receipt for systemic unfairness.

[i]Various Contributors, ‘Reddit Discussion on High Soup Prices’ (Online Forum, 2023) https://www.reddit.com/r/CasualUK/comments/1eooo3o/why_has_soup_gotten_so_expensive

[ii] Philip J Carstairs, ‘A generous helping? The archaeology of Soup Kitchens and their role in post-medieval philanthropy 1790-1914 (PhD Thesis, University of Leicester 2022) https://figshare.le.ac.uk/articles/thesis/A_generous_helping_The_archaeology_of_soup_kitchens_and_their_role_in_post-medieval_philanthropy_1790-1914/21187117?file=37564186

[iii] Soup – etymology, origin & meaning[iii] https://www.etymonline.com/word/soup

[iv] Philip J Carstairs, ‘A generous helping? The archaeology of soup kitchens and their role in post-medieval philanthropy 1790–1914’ (Summary, University of Leicester 2022)(https://figshare.le.ac.uk/articles/thesis/A_generous_helping_The_archaeology_of_soup_kitchens_and_their_role_in_post-medieval_philanthropy_1790-1914/21187117)

[v] ONS, ‘Food Inflation Data, UK: August 2025’ (Trading Economics Data) https://tradingeconomics.com/united-kingdom/food-inflation

[vi] The Trussell Group-End Of Year Foodbank Stats

https://www.trussell.org.uk/news-and-research/latest-stats/end-of-year-stats

[vii] GlobalData, ‘Ambient Soup Market Size, Growth and Forecast Analytics, 2023-2028’ (Market Report, 2023) https://www.globaldata.com/store/report/uk-ambient-soup-market-analysis/

[viii] ONS, ‘Consumer Prices Index, UK: August 2025’ (Summary) https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/inflationandpriceindices

[ix] Food Standards Agency, ‘Food System Strategic Assessment’ (March 2023) https://www.food.gov.uk/research/food-system-strategic-assessment-trends-and-issues-impacted-by-uk-economic-condition

[x] Wholesale Soup Mixes (Brakes Foodservice) https://www.brake.co.uk/dry-store/soup/ambient-soup/bulk-soup-mixes

[xii] A Semuels, ‘Why Food Company Profits Make Groceries Expensive’ (Time Magazine, 2023) https://time.com/6269366/food-company-profits-make-groceries-expensive/

[xiii] Christopher B Barrett and others, ‘Poverty Traps’ (NBER Working Paper No. 13828, 2008) https://www.nber.org/system/files/chapters/c13828/c13828.pdf

[xiv] Philip J Carstairs, ‘A generous helping? The archaeology of soup kitchens and their role in post-medieval philanthropy 1790–1914’ (Summary, University of Leicester 2022)(https://figshare.le.ac.uk/articles/thesis/A_generous_helping_The_archaeology_of_soup_kitchens_and_their_role_in_post-medieval_philanthropy_1790-1914/21187117

[xv] Philip J Carstairs, ‘A generous helping? The archaeology of soup kitchens and their role in post-medieval philanthropy 1790–1914’ (Summary, University of Leicester 2022)(https://figshare.le.ac.uk/articles/thesis/A_generous_helping_The_archaeology_of_soup_kitchens_and_their_role_in_post-medieval_philanthropy_1790-1914/21187117

[xvi] The Soup Kitchens of Spitalfields (Blog, 2019) https://spitalfieldslife.com/2019/05/15/the-soup-kitchens-of-spitalfields/

[xvii] Birmingham History Blog, ‘Soup for the Poor’ (2016) https://birminghamhistoryblog.wordpress.com/2016/02/04/soup-for-the-poor/

[xviii] [xviii] Philip J Carstairs, ‘A generous helping? The archaeology of soup kitchens and their role in post-medieval philanthropy 1790–1914’ (Summary, University of Leicester 2022)(https://figshare.le.ac.uk/articles/thesis/A_generous_helping_The_archaeology_of_soup_kitchens_and_their_role_in_post-medieval_philanthropy_1790-1914/21187117

[xix] Journal Panorama, ‘Feeding the Conscience: Depicting Food Aid in the Popular Press’ (2019) https://journalpanorama.org/article/feeding-the-conscience/

[xx] Journal Panorama, ‘Feeding the Conscience: Depicting Food Aid in the Popular Press’ (2019) https://journalpanorama.org/article/feeding-the-conscience/

[xxi] Joseph Roth, Hotel Savoy (Quote on Soup Kitchens) https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/tag/soup-kitchens

[xxii] Convoy of Hope, (Quotes on Dignity and Poverty) https://convoyofhope.org/articles/poverty-quotes/

[xxiii] Philip J Carstairs, ‘A generous helping? The archaeology of soup kitchens and their role in post-medieval philanthropy 1790–1914’ (Summary, University of Leicester 2022)(https://figshare.le.ac.uk/articles/thesis/A_generous_helping_The_archaeology_of_soup_kitchens_and_their_role_in_post-medieval_philanthropy_1790-1914/21187117

[xxiv] Science Museum Group, ‘Photographs of Poverty and Welfare in 1930s Britain’ (Blog, 2017) https://blog.scienceandmediamuseum.org.uk/photographs-of-poverty-and-welfare-in-1930s-britain/

[xxv] AJ P Taylor, (Quote on Revolution) https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/tag/soup-kitchens

[xxvi] House of Commons Library, ‘Food poverty: Households, food banks and free school meals’ (CBP-9209, 2024) https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-9209/

[xxvii] Trussell Trust, ‘Factsheets and Data’ (2024/25) https://www.trussell.org.uk/news-and-research/latest-stats/end-of-year-stats

[xxviii] The Guardian, ‘Failure to tackle child poverty UK driving discontent’ (2025) https://www.theguardian.com/society/2025/sep/10/failure-tackle-child-poverty-uk-driving-discontent

[xxix] Charity Link, ‘The cost of living crisis and the impact on UK charities’ (Blog) https://www.charitylink.net/blog/cost-of-living-crisis-impact-uk-charities

[xxxi] The Soup Kitchen (Boynton Beach), ‘History’ https://thesoupkitchen.org/home/history/

[xxxii] Transforming Society, ‘4 uncomfortable realities of food charity’ (Blog, 2023) https://www.transformingsociety.co.uk/2023/12/01/4-uncomfortable-realities-of-food-charity-power-religion-race-and-cash

[xxxiii] The Trussell Group-End Of Year Foodbank Stats

https://www.trussell.org.uk/news-and-research/latest-stats/end-of-year-stats

[xxxiv] The Guardian, ‘Food banks are not the answer’ (2023) https://www.theguardian.com/society/2023/jun/29/food-banks-are-not-the-answer-charities-search-for-new-way-to-help-uk-families

[xxxv] The Guardian, ‘Britain’s hunger and malnutrition crisis demands structural solutions’ (2023) https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/commentisfree/2023/dec/27/britain-hunger-malnutrition->

[xxxvi] Jacques Diouf, (Quote on Hunger and Justice, 2007) https://www.hungerhike.org/quotes-about-hunger/

[xxxvii] Borgen Magazine, ‘Hunger Awareness Quotes’ (2024) https://www.borgenmagazine.com/hunger-awareness-quotes/

[xxxviii] he Guardian, ‘Failure to tackle child poverty UK driving discontent’ (2025) https://www.theguardian.com/society/2025/sep/10/failure-tackle-child-poverty-uk-driving-discontent

[xxxix] Charities Aid Foundation, ‘Cost of living: Charity donations can’t keep up with rising costs and demand’ (Press Release, 2023) https://www.cafonline.org/home/about-us/press-office/cost-of-living-charity-donations-can-t-keep-up-with-rising-costs-and-demand

[xl] The “Hunger Industrial Complex” and Public Health Policy (Journal Article, 2022) https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9437921/

Sabrina Carpenter and Feminist Utopia

I have recently been introduced to Sabrina Carpenter via online media commentary about the image of her new album cover Man’s Best Friend. Whilst some claim the image is playing with satire, the image appears to have been interpreted by others as being hyper-sexual and pandering to the male gaze.

I am not sure why this specific album cover and artist has attracted so much attention given that the hyper-sexual depiction of women is well-represented within the music industry and society more generally. However, because Sabrina’s main audience base is apparently young women under 30 it did leave me thinking about the module CRI1009 and feminist utopia, as it left me with questions that I would want to ask the students like: In a feminist utopia should the hyper-sexualized imagery of women exist?

Some might be quick to point out that this imagery should not exist as it could be seen to contribute towards the misogynistic sexualisation of women and the danger of this, as illustrated with Glasgow Women’s Aid comments about Sabrina’s album cover via Instagram (2025)

‘Sabrina Carpenter’s new album cover isn’t edgy, it’s regressive.

Picturing herself on all fours, with a man pulling her hair and calling it “Man’s Best Friend” isn’t subversion. 😐

It’s a throwback to tired tropes that reduce women to pets, props, and possessions and promote an element of violence and control. 🚩

We’ve fought too hard for this. ✊🏻

We get Sabrina’s brand is packaged up retro glam but we really don’t need to go back to the tired stereotypes of women. ✨

Sabrina is pandering to the male gaze and promoting misogynistic stereotypes, which is ironic given the majority of her fans are young women!

Come on Sabrina! You can do better! 💖’

However, thinking about utopia is always complicated as Sabrina’s brand appears to some a ‘sex-positive feminism’ by apparently allowing women to be free to represent themselves and ‘feel sexy’ rather than being controlled by the rules and expectations of other people. For some this idea of sexual freedom aka ‘sex-positive feminism’ branded via an inequitable capitalistic male dominated industry and represented by an incredibly rich white woman would be a bit of a mythical representation. As while this idea of sexy feminism is promoted by the privileged few this occurs in a societal context where many feel that women’s rights are being/at risk of being eroded and women are being subjected to sexual violence on a daily basis.

I am not sure what a workshop discussion with CRI1009 students would conclude about this, but certainly there would need to be a circling back to more never- ending foundational questions about utopia: what else would exist in this feminist utopia? Whose feminist utopic vision should get priority? Would anyone be damaged in a utopic society that does promote this hyper-sexualization? If so, should this utopia prioritise individual expression or have collective responsibility? In a society without hyper-sexualisation of women would there be rule breakers, and if so, what do you do with them?

The future of criminology

If you have an alert on your phone then a new story may come with a bing! the headline news a combination of arid politics and crime stories. Sometimes some spicy celebrity news and maybe why not a scandal or two. We are alerted to stories that bing in our phone to keep ourselves informed. Only these are not stories, they are just headlines! We read a series of headlines and form a quick opinion of anything from foreign affairs, transnational crime, war, financial affairs to death. We are informed and move on.

There is a distinction, that we tend not to make whenever we are getting our headline alerts; we get fragments of information, in a sea of constant news, that lose their significance once the new headline appears. We get some information, but never the knowledge of what really happened. We hear of war but we hardly know the reasons for the war. We read on financial crisis but never capture the reason for the crisis. We hear about death, usually in crime stories, and take notice of the headcount as if that matters. If life matters then a single loss of life should have an impact that it deserves irrespective of origin.

After a year that forced me to reflect deeply about the past and the future, I often questioned if the way we consume information will alter the way we register social phenomena and more importantly we understand society and ourselves in it. After all crime stories tend to be featured heavily in the headlines. Last time I was imagining the “criminology of the future” it was terrorism and the use of any object to cause harm. That was then and now some years later we still see cars being used as weapons, fear of crime is growing according to the headlines that even the official stats have paused surveying since 2017! Maybe because in the other side of the Atlantic the measurement of fear was revealed to be so great that 70% of those surveyed admitted being afraid of crime, some of whom to the extent that changes their everyday life.

We are afraid of crime, because we read the headlines. If knowledge is power, then the fragmented information is the source of ambiguity. The emergence of information, the reproduction of news, in some cases aided by AI have not provided any great insight or understanding of what is happening around us. A difference between information and knowledge is the way we establish them but more importantly how we support them. In a world of 24/7 news updates, we have no ideological appreciation of what is happening. Violence is presented as a phenomenon that emerges under the layers of the dark human nature. That makes is unpredictable and scary. Understandably so…

This a representation of violence devoid of ideology and theory. What is violence in our society does not simply happens but it is produced and managed through the way it is consumed and promoted. We sell violence, package it for patriotic fervour. We make defence contracts, selling weapons, promoting war. In society different social groups are separated and pitted against each other. Territory becomes important and it can be protected only through violence. These mechanisms that support and manage violence in our society are usually omitted. A dear colleague quite recently reminded me that the role of criminology is to remind people that the origins of crime are well rooted in our society in the volume of harm it inflicts.

There is no singular way that criminology can develop. So far it appears like this resilient discipline that manages to incorporates into its own body areas of work that fiercely criticised it. It is quite ironic for the typical criminology student to read Foucault, when he considered criminology “a utilitarian discipline”! Criminology had the last laugh as his work on discipline and punishment became an essential read. The discipline seems to have staying power but will it survive the era of information? Most likely; crime data originally criticised by most, if not all criminologists are now becoming a staple of criminological research methods. Maybe criminology manages to achieve what sociology was doing in the late 20th century or maybe not! Whatever direction the future of criminology takes it will be because we have taken it there! We are those who ought to take the discipline further so it would be relevant in years to come. After all when people in the future asked you what did you do…you better have a good answer!

Changing the Narrative around Violence Against Women and Girls

For Criminology at UON’s 25th Birthday, in partnership with the Northampton Fire, Police and Crime Commissioner, the event “Changing the Narrative: Violence Against Women and Girls” convened on the 2nd April. Bringing together a professional panel, individuals with lived experience and practitioners from charity and other sectors, to create a dialogue and champion new ways of thinking. The first in a series, this event focused on language.

All of the discussions, notes and presentations were incredibly insightful, and I hope this thematic collation does it all justice.

“A convenient but not useful term.”

Firstly an overwhelming reflection on the term itself; ‘Violence Against Women and Girls’ – does it do justice to all of the behaviour under it’s umbrella? We considered this as reductionist, dehumanising, and often only prompts thinking and action to physical acts of violence, but perhaps neglects many other harms such as emotional abuse, coercion and financial abuse which may not be seen as, or felt as ‘severe enough’ to report. It may also predominantly suggest intimate partner or domestic abuse which may too exclude other harms towards women and girls such as (grand)parent/child abuse or that which happens outside of the home. All of which are too often undetected or minimised, potentially due to this use of language. Another poignant reflection is that we may not currently be able to consider ‘women and girls’ as one group, given that girls under 16 may not be able to seek help for domestic abuse, in the same way that women may be able to. We also must consider the impact of this term on those whose gender identity is not what they were assigned at birth, or those that identify outside of the gender binary. Where do they fit into this?

To change the narrative, we must first identify what we are talking about. Explicitly. Changing the narrative starts here.

“I do not think I have survived.”

We considered the importance of lived experience in our narratives and reflected on the way we use it, and what that means for individuals, and our response.

Firstly, the terms ‘victim’ and ‘survivor’ – which we may use without thought, use as fact, particularly as descriptors within our professions, but actually these are incredibly personal labels that only individuals with such experience can give to themselves. This may be reflective of where they are in their journey surrounding their experiences and have a huge impact on their experience of being supported. It was courageously expressed that we also must recognise that individuals may not identify with either of those terms, and that much more of that person still exists outside of that experience or label. We also took a moment to remember that some victims, will never be survivors.

Lived experience is making its way into our narratives more and more, but there is still much room for improvement. We champion that if we are to create a more supportive, inclusive, practical and effective narrative, we must reflect the language of individuals with lived experience and we must use it to create a narrative free from tick boxes, from the lens of organisational goals and societal pressure.

Lived experience must be valued for what it is, not in spite of what it is.

“In some cases, we allow content – which would otherwise go against our standards – if its newsworthy.”

A further theme was a reflection on language which appears to be causing an erosion of moral boundaries. For example, the term ‘misogyny’ – was considered to be used flippantly, as an excuse, and as a scapegoat for behaviour which is not just ‘misogynistic’ but unacceptable, abhorrent, inexcusable behaviour – meaning the extent of the harms caused by this behaviour are swept away under a ‘normalised’ state of prejudice.

This is one of many terms that along with things like ‘trauma bond’ and ‘narcissist’ which have become popular on social media without any rigour as to the correct use of the term – further normalises harmful behaviour, and prevents women and girls from seeking support for these very not normal experiences. In the same vein it was expressed that sexual violence is often seen as part of ‘the university experience.’

This use of language and its presence on social media endangers and miseducates, particularly young people, especially with new posting policies around the freedom of expression. Firstly, in that many restrictions can be bypassed by the use of different text, characters and emoji so that posts are not flagged for certain words or language. Additionally, guidelines from Meta were shared and highlighted as problematic as certain content which would, and should, normally be restricted – can be shared – as long as is deemed ‘newsworthy.’

Within the media as a whole, we pressed the importance of using language which accurately describes the actions and experience that has happened, showing the impact on the individual and showing the extent of the societal problem we face… not just what makes the best headline.

“We took action overnight for the pandemic.”

Language within our response to these crimes was reflected upon, in particular around the term ‘non-emergency’ which rape, as a crime, has become catalogued as. We considered the profound impact of this language for those experiencing/have experienced this crime and the effect it has on the resources made available to respond to it.

Simultaneously, in other arenas, violence toward women and girls is considered to be a crisis… an emergency. This not only does not align with the views of law enforcement but suggests that this is a new, emerging crisis, when in fact it is long standing societal problem, and has faced significant barriers in getting a sufficient response. As reflected by one attendee – “we took action overnight for the pandemic.”

“I’ve worked with women who didn’t report rape because they were aroused – they thought they must have wanted it.”

Education was another widely considered theme, with most talk tables initially considering the need for early education and coming to the conclusion that everyone needs more education; young and old – everything in between; male, female and everything in between and outside of the gender binary. No-one is exempt.

We need all people to have the education and language to pass on to their children, friends, colleagues, to make educated choices. If we as adults don’t have the education to pass on to children, how will they get it? The phrase ‘sex education’ was reflected upon, within the context of schools, and was suggested to require change due to how it triggers an uproar from parents, often believing their children will only be taught about intercourse and that they’re too young to know. It was expressed that age appropriate education, giving children the language to identify harms, know their own body, speak up and speak out is only beneficial and this must happen to help break the cycle of generational violence. We cannot protect young people if we teach them ignorance.

Education for all was pressed particularly around education of our bodies, and our bodily experiences. In particular of female bodies, which have for so long been seen as an extension of male bodies. No-one knows enough about female bodies. This perpetuates issues around consent, uneducated choices and creates misplaced and unnecessary guilt, shame and confusion for females when subjected to these harms.

“Just because you are not part of the problem, does not mean you are part of the solution.“

Finally, though we have no intention or illusion of resolution with just one talk, or even a series of them – we moved to consider some ways forward. A very clear message was that this requires action – and this action should not fall on women and girls to protect themselves, but for perpetrators for be stopped. We need allies, of all backgrounds, but in particular, we need male allies. We need male allies who have the education, and the words necessary to identify and call out the behaviour of their peers, their friends, their colleagues, of strangers on the bus. We asked – would being challenged by a ‘peer’ have more impact? Simply not being a perpetrator, is not enough.

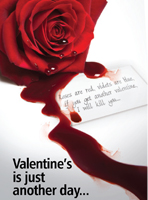

St Valentines Day! Love and other emotions

This blog today is all about love…. or maybe not! As criminologists, we tend to see things slightly different, and our perspective is influenced by functions other than undying declarations of love.

Saint Valentine is associated with love and people celebrate the day with their special romantic person, or by pursuing any person of interest, with romantic cards. Greeting cards, bottles of wine, boxes of chocolates, bunches of flowers, heart shaped jewellery, lovely sonnets, sexy underwear, kinky gifts and over the top romantic gestures! All of the above are anticipated actions on this day. Any of these will act as a demonstration of love. In some ways the more enormous the gesture the greater the demonstration of love and intimacy to the intended special person. Many times, we hear those in a relationship rut complaining that “they don’t even buy me chocolates anymore” a sign that love has fizzled out.

Love is a powerful emotion, and I dare not to challenge it. Artists have created their best work on love! Religion has created its strongest appeal on love. People, the world over, have based their entire lives of how they feel about a person they choose to be their partner and share their lives with. So clearly love is important! Enough for an Austrian psychotherapist to create an entire theory on love and sex. We feel ready to go to war for love and we are completely convinced that love is the force that keeps us going. Love is strong and we feel it every day.

Therefore, it is slightly surprising that the patron saint of romantic love is a rather fictional character! The saint is meant to be a priest who lived in the 3rd century AD and martyred by tortured for his faith. There was no romance involved and there were no love poems written of the time. In fact, the Roman Catholic church did not recognise or mentioned this martyrdom at the time. The first accounts on St Valentine appear in the 6th and later the 9th centuries, some centuries later. Since then, the story of the saint is embellished further, until the 19th century when it becomes connected with romantic love in some tenuous way. For example, the more recent narratives claim that before his execution he would convert and cure the daughter of his jailer. He was also officiating wedding ceremonies between Christians which may have given him the romantic connection. In the 19th century we have the first mass production of love tokens dedicated to the day and in the 20th, century especially post 1960s the celebration was growing in popularity and appeal. Currently the day is a celebration that has a significant capitalist value. It is usually a commercial success midway between Christmas and Easter.

Some religious historians noted that in the Roman calendar in February there have been rituals and celebrations on fertility and cleanliness (physical, spiritual). It was the time presumably when young Romans prepared for sexual relations. Therefore, an amalgamation of the old practices and the then new religion overlap with an obscure Saint to act as the glue to connect them and reaffirm the importance of love. Ironically the Roman citizens of the time, in particular the patricians, would not recognise such acts! They married out of interest, connecting the wealth and power of different factions. In those cycles love was more of a chimera rather than a reality.

Romantic love with knights, towers, dragons and gestures of devotion will appear as fanciful tales. Who hasn’t heard of Odysseus and his beloved wife Penelope who remained faithful to him for 20 years! Her fidelity was not reciprocated, and Odysseus had multiple affairs and fathered several children across the Mediterranean. Not quite the romantic story people would like to believe. Romantic love was always a tale, with vivid twists and turns. Love appears almost pure, undiluted that lifts those in its path. Shakespeare wrote fantastic sonnets on love. Some of the best things ever written in English. Still his contemporaries did not recognise this love. The majority of people at the time died young, malnourished and exhausted. Those who barely survive cannot afford to embrace love. As for those in power their relationship with love can be summed up in the old mnemonic rhyme “divorced, beheaded, died; divorced, beheaded, survived”!

We presume that romantic love is a representation of two people having feelings for one other. That is a nice sentiment but historically weak. Love for women does not exist. Not because women are devoid of emotions; quite the contrary! Because women have been used in social transactions between men who barter and use them as part of their household. A feminist today can recognise, despite all assurances for equality, how unequal life is. Especially in the household! If anyone wants to see why love is not equal only see how domestic and intimate violence is spread between gender lines. Because St Valentine brings flowers and chocolates, but it also brings beatings and abuse. Across the year it is during holidays and significant dates, including St Valentines that violence against women surges. One can unfortunately deduce that love is not for women. Oh…. The irony as romantic novels and movies are presented mostly for women as “chick flicks”!

Earlier in this post, it was said that the bigger the romantic move the better! Who will do this big romantic gesture? A man with chivalrous intent. Our household data reveal that men will spend more than double on what women will spend on the day, making their romantic intent more obvious. Perhaps men are more romantic and feel the need to satisfy that internal need. Or maybe there are other emotions at play. Love is very powerful, but so is possessiveness. In a history of transactions men used women for trading, so their gestures may be a latent act of dominance, a fresh reminder of possession. Instead of giving them chocolates, you may as well urinate all over them. That way your beloved will have your scent and keep other suitors away. So, this is not love but control, jealousy and dominance. Every drop of wine, every piece of chocolate, every flower petal, is yet another link in the chain of ownership. In case this gets misunderstood, the individual who buys flowers isn’t a villain, but the history of this kind of love is pointing in this direction. Your partner may have the best intentions and the greatest love and regard for you, but our society has never really acknowledged the transactional relationship between men and women. It is similar to those who speak of the evils of slavery, but with no recognition of reparations. This love is not pure and clean. It is the darkest form of patriarchy that controls people making them to believe in an adult fairytale once the other story of Santa Claus is not believed any more.

Romantic actions target all incomes and all ages, but of course there is a drive to get younger people, new generations of customers, on the love spending machine. At this stage I shall write…what not to do when you are planning a romantic day! Do not go overboard. Love is something felt in the heart not in the pocket. Heart-shaped products do not say “I love you” more than square or round ones! Red is no more appealing than any other colour and of course if emotions are high, they tend to last more than a day! Ideally do not spend any money! In the unfortunate event that you do, do not cook your romantic meal with a sharp knife. You may pierce the palm of your hand and end up with stitches. Do not spread chocolate on a partner before establishing if they are allergic to any of the ingredients, you may end up in A&E. Do not offer them wine, if they have an intolerance to alcohol, they may vomit all over your pristine bedspread. Do not write something funny or profound if they are thick and unable to comprehend deeper meanings (in that case what are you doing with them???). Love is not an idea, a moment, a day, an instant. It is a lifetime however long or short it is. You will live in love and you will die in love. Even when you are by yourself love is in you and it cannot be defined by the actions of people around you. Finally, love is selfless so do not try to control them, “love is a rebellious bird that nobody can tame”!

25 years of Criminology

When the world was bracing for a technological winter thanks to the “millennium bug” the University of Northampton was setting up a degree in Criminology. Twenty-five years later and we are reflecting on a quarter of a century. Since then, there have been changes in the discipline, socio-economic changes and wider changes in education and academia.

The world at the beginning of the 21st century in the Western hemisphere was a hopeful one. There were financial targets that indicated a raising level of income at the time and a general feeling of a new golden age. This, of course, was just before a new international chapter with the “war on terror”. Whilst the US and its allies declared the “war on terror” decreeing the “axis of evil”, in Criminology we offered the module “Transnational Crime” talking about the challenges of international justice and victor’s law.

Early in the 21st century it became apparent that individual rights would take centre stage. The political establishment in the UK was leaving behind discussions on class and class struggles and instead focusing on the way people self-identify. This ideological process meant that more Western hemisphere countries started to introduce legal and social mechanisms of equality. In 2004 the UK voted for civil partnerships and in Criminology we were discussing group rights and the criminalisation of otherness in “Outsiders”.

During that time there was a burgeoning of academic and disciplinary reflection on the way people relate to different identities. This started out as a wider debate on uniqueness and social identities. Criminology’s first cousin Sociology has long focused on matters of race and gender in social discourse and of course, Criminology has long explored these social constructions in relation to crime, victimisation and social precipitation. As a way of exploring race and gender and age we offered modules such as “Crime: Perspectives of Race and Gender” and “Youth, Crime and the Media”. Since then we have embraced Kimberlé Crenshaw’s concept of intersectionality and embarked on a long journey for Criminology to adopt the term and explore crime trends through an increasingly intersectional lens. Increasingly our modules have included an intersectional perspective, allowing students to consider identities more widely.

The world’s confidence fell apart when in 2008 in the US and the UK financial institutions like banks and other financial companies started collapsing. The boom years were replaced by the bust of the international markets, bringing upheaval, instability and a lot of uncertainty. Austerity became an issue that concerned the world of Criminology. In previous times of financial uncertainty crime spiked and there was an expectation that this will be the same once again. Colleagues like Stephen Box in the past explored the correlation of unemployment to crime. A view that has been contested since. Despite the statistical information about declining crime trends, colleagues like Justin Kotzé question the validity of such decline. Such debates demonstrate the importance of research methods, data and critical analysis as keys to formulating and contextualising a discipline like Criminology. The development of “Applied Criminological Research” and “Doing Research in Criminology” became modular vehicles for those studying Criminology to make the most of it.

During the recession, the reduction of social services and social support, including financial aid to economically vulnerable groups began “to bite”! Criminological discourse started conceptualising the lack of social support as a mechanism for understanding institutional and structural violence. In Criminology modules we started exploring this and other forms of violence. Increasingly we turned our focus to understanding institutional violence and our students began to explore very different forms of criminality which previously they may not have considered. Violence as a mechanism of oppression became part of our curriculum adding to the way Criminology explores social conditions as a driver for criminality and victimisation.

While the world was watching the unfolding of the “Arab Spring” in 2011, people started questioning the way we see and read and interpret news stories. Round about that time in Criminology we wanted to break the “myths on crime” and explore the way we tell crime stories. This is when we introduced “True Crimes and Other Fictions”, as a way of allowing students and staff to explore current affairs through a criminological lens.

Obviously, the way that the uprising in the Arab world took charge made the entire planet participants, whether active or passive, with everyone experiencing a global “bystander effect”. From the comfort of our homes, we observed regimes coming to an end, communities being torn apart and waves of refugees fleeing. These issues made our team to reflect further on the need to address these social conditions. Increasingly, modules became aware of the social commentary which provides up-to-date examples as mechanism for exploring Criminology.

In 2019 announcements began to filter, originally from China, about a new virus that forced people to stay home. A few months later and the entire planet went into lockdown. As the world went into isolation the Criminology team was making plans of virtual delivery and trying to find ways to allow students to conduct research online. The pandemic rendered visible the substantial inequalities present in our everyday lives, in a way that had not been seen before. It also made staff and students reflect upon their own vulnerabilities and the need to create online communities. The dissertation and placement modules also forced us to think about research outside the classroom and more importantly outside the box!

More recently, wars in Europe, the Middle East, Africa and Asia have brought to the forefront many long posed questions about peace and the state of international community. The divides between different geopolitical camps brought back memories of conflicts from the 20th century. Noting that the language used is so old, but continues to evoke familiar divisions of the past, bringing them into the future. In Criminology we continue to explore the skills required to re-imagine the world and to consider how the discipline is going to shape our understanding about crime.

It is interesting to reflect that 25 years ago the world was terrified about technology. A quarter of a century later, the world, whilst embracing the internet, is worriedly debating the emergence of AI, the ethics of using information and the difference between knowledge and communication exchanges. Social media have shifted the focus on traditional news outlets, and increasingly “fake news” is becoming a concern. Criminology as a discipline, has also changed and matured. More focus on intersectional criminological perspectives, race, gender, sexuality mean that cultural differences and social transitions are still significant perspectives in the discipline. Criminology is also exploring new challenges and social concerns that are currently emerging around people’s movements, the future of institutions and the nature of society in a global world.

Whatever the direction taken, Criminology still shines a light on complex social issues and helps to promote very important discussions that are really needed. I can be simply celebratory and raise a glass in celebration of the 25 years and in anticipation of the next 25, but I am going to be more creative and say…

To our students, you are part of a discipline that has a lot to say about the world; to our alumni you are an integral part of the history of this journey. To those who will be joining us in the future, be prepared to explore some interesting content and go on an academic journey that will challenge your perceptions and perspectives. Radical Criminology as a concept emerged post-civil rights movements at the second part of the 20th century. People in the Western hemisphere were embracing social movements trying to challenge the established views and change the world. This is when Criminology went through its adolescence and entered adulthood, setting a tone that is both clear and distinct in the Social Sciences. The embrace of being a critical friend to these institutions sitting on crime and justice, law and order has increasingly become fractious with established institutions of oppression (think of appeals to defund the police and prison abolition, both staples within criminological discourse. The rigour of the discipline has not ceased since, and these radical thoughts have led the way to new forms of critical Criminology which still permeate the disciplinary appeal. In recent discourse we have been talking about radicalisation (which despite what the media may have you believe, can often be a positive impetus for change), so here’s to 25 more years of radical criminological thinking! As a discipline, Criminology is becoming incredibly important in setting the ethical and professional boundaries of the future. And don’t forget in Criminology everyone is welcome!

Uncertainties…

Sallek Yaks Musa

Who could have imagined that, after finishing in the top three, James Cleverly – a frontrunner with considerable support – would be eliminated from the Conservative Party’s leadership race? Or that a global pandemic would emerge, profoundly impacting the course of human history? Indeed, one constant in our ever-changing world is the element of uncertainty.

Image credit: Getty images

The COVID-19 pandemic, which emerged in late 2019, serves as a stark reminder of our world’s interconnectedness and the fragility of its systems. When the virus first appeared, few could have foreseen its devastating global impact. In a matter of months, it had spread across continents, paralyzing economies, overwhelming healthcare systems, and transforming daily life for billions. The following 18 months were marked by unprecedented global disruption. Lockdowns, travel restrictions, and social distancing became the new norms, forcing us to rethink how we live, work, and interact.

The economic fallout was equally staggering. Supply chains crumbled, unemployment surged, and entire industries teetered on the brink of collapse. Education was upended as schools and universities hastily shifted online, exposing the limitations of existing digital infrastructure. Yet, amid the chaos, communities displayed remarkable resilience and adaptability, demonstrating the need for flexibility in the face of uncertainty.

Beyond health crises, the ongoing climate and environmental emergencies continue to fuel global instability. Floods, droughts, erratic weather patterns, and hurricanes such as Helene and Milton not only disrupt daily life but also serve as reminders that, despite advances in meteorology, no amount of preparedness can fully shield us from the overwhelming forces of nature.

For millions, however, uncertainty isn’t just a concept; it’s a constant reality. The freedom to choose, the right to live peacefully, and the ability to build a future are luxuries for those living under the perpetual threat of violence and conflict. Whether in the Middle East, Ukraine, or regions of Africa, where state and non-state actors perpetuate violence, people are forced to live day by day, confronted with life-threatening uncertainties.

On a more optimistic note, some argue that uncertainty fosters innovation, creativity, and opportunity. However, for those facing existential crises, innovation is a distant luxury. While uncertainty may present opportunities for some, for others, it can be a path to destruction. Life often leaves little room for choice, but when faced with uncertainty, we must make decisions – some minor, others, life-altering. Nonetheless, I am encouraged that while we may not control the future, we must navigate it as best we can, and lead our lives with the thought and awareness that, no one knows tomorrow.