Home » Stanley Cohen

Category Archives: Stanley Cohen

‘Gentleminions’: the rise of…media demonisation?

Recently one of the main ‘stories’ which appear to be filling up my newsfeeds on social media, is around the latest TikTok trend: ‘Gentleminions’ and the havoc this appears to be causing Cinemas. I am yet to see the film Minions 2: The Rise of Gru but have no doubt I will as a fan of the little, yellow and mischievous title characters, and their ‘villainous’ boss. However, what has become apparent from reading the news articles which have come about from the TikTok trend and the “terrible menace” these ‘gentleminions’ pose (Heritage, 2022), is that yet again, the media appear to be demonising young people and their pastimes, something which has been fairly consistent since the emergence of the independent press back in Victorian England.

The trend involves, “teenagers”, “young people”, “youngsters” and/or “kids” watching Minions 2 dressed in formalwear as an imitation of some ‘famous’ TikTok users (Gill, 2022; Heritage, 2022; Hirwani, 2022). Seems pretty harmless, however there have been reports of “shouting and mimicking the minions” (Hirwani, 2022), “honk full volume gibberish” (Heritage, 2022), “rowdy behaviour from groups of teens” (Gill, 2022). Again, all seems fairly harmless, albeit possibly annoying. Yet, there have also been reports of “vandalism, throwing objects and abusing staff” (Gill, 2022). What I can’t help but utter is a sense of: here we go again, in relation to young people and the next wave of nuisance or harm they pose to society. It verges on the notion of demonising young people for being young people… something the British media is all to well versed in.

My thoughts wonder back to the infamous media portrayal of events which occurred on the Bank Holiday weekend back in 1964 with those violent and dangerous young people affiliated with the Mods and Rockers… oh wait a minute! That was a misrepresentation and portrayal of events which lead to what we know recognise as a moral panic (excuse the oversimplification). I wonder if this ‘gentleminion’ trend will follow suit? The media has consistently reported on the nuisance these young people are causing and the refunds given by cinemas to unhappy customers who have been unable to enjoy the film. Focusing on the damage caused by these youngsters in vague terms and without any real evidence. It is interesting that the media flocks to the negative portrayal of these youth, mirroring Hendrick’s (2015) point that children and their pastimes represent a moral threat to society, hence the continual interest in them.

The Guardian’s portrayal is slightly more positive, whilst including the narrative of the “terrible menace” these ‘Gentleminions’ pose, Heritage (2022) also presents the idea that this trend could be a positive trend for cinema and film considering the struggles they faced with the pandemic and the uprising of streaming services. Who knows: maybe cinema will take Heritage’s (2022) idea about having select screenings to allow and encourage young people to attend the film and practice their ‘gibberish’, whilst allowing other film goers the chance to view the film without the distraction? More than likely, true to form, this will all blow over in a week or so, but it does make you wonder why the media haven’t learned from previous experience and doesn’t just “leave them kids alone” (Pink Floyd, 1972).

References:

Cohen, S. (2002) Folk Devils and Moral Panics, 3rd edn. London: Routledge.

Gill, E. (2022) Cinemas banning teens in suits from watching Minions amid TikTok #gentleminions trend, Manchester Evening News, 6th July [online], Available at: https://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/news/greater-manchester-news/minions-movie-wearing-suits-banned-24411350 [Accessed 6th July 2022].

Hendrick, H. (2015) Histories of youth crime and youth justice. In: Goldson, B. and Muncie, J. (eds.) Youth Crime and Justice. 2nd ed. London: Sage Publications, pp.1-16.

Heritage, S. (2022) The teens disrupting Minions screenings might actually be the saviours of cinema, The Guardian, 5th July [online], Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2022/jul/05/teens-disrupting-minions-screenings-gentleminions-despicable-me-rise-of-gru [Accessed 6th July 2022].

Hirwani, P. (2022) Minions: Cinemas ban teens in suits following the ‘gentleminions’ TikTok trend, The Independent, 5th July [online], Available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/films/news/minions-theatres-ban-gentleminions-teens-b2115800.html [Accessed 6th July 2022].

Pink Floyd (1972) Another Brick in the Wall, Pt 2 (2011 Remastered), Available from: Amazon Music [Accessed 6th July 2022].

Criminology 2020 AD

2020 will be a memorable year for a number of reasons. The big news of course was people across the world going into lockdown and staying home in order to stop the transmission of a coronavirus Covid-19. Suddenly we started counting; people infected, people in hospitals, people dead. The social agenda changed and our priorities altered overnight. During this time, we are trying to come to terms with a new social reality, going for walks, knitting, baking, learning something, reading or simply surviving, hoping to see the end of something so unprecedented.

People are still observing physical distancing, and everything feels so different from the days we were discussing future developments and holiday plans. During the last days before lockdown we (myself and @paulaabowles) were invited to the local radio by April Dawn to talk about, what else, but criminology. In that interview we revealed that the course started 20 years ago and for that reason we shall be having a big party inviting prospective, current and old students together to mark this little milestone. Suffice to say, that did not happen but the thought of celebrating and identifying the path of the programme is very much alive. I have written before about the need to celebrate and the contributions our graduates make to the local, regional and national market. Many of whom have become incredibly successful professionals in the Criminal Justice System.

On this entry I shall stand on something different; the contribution of criminology to professional conduct, social sciences and academia. Back in the 1990s Stan Cohen, wrote the seminal Against Criminology, a vibrant collection of essays, that identified the complexity of issues that once upon a time were identified as radical. Consider an academic in the 1960s imagining a model that addresses the issue of gender equality and exclusion; in some ways things may not have changed as much as expected, but feminism has entered the ontology of social science.

Criminology as a discipline did not speak against the atrocities of the Nazi genocide, like many other disciplines; this is a shame which consecutive generations of colleagues since tried to address and explain. It was in the 1960s that criminology entered adulthood and embraced one of its more fundamental principles. As a theoretical discipline, which people outside academia, thought was about reading criminal minds or counting crime trends only. The discipline, (if it is a discipline) evolved in a way to bring a critical dimension to law and order. This was something more than the original understanding of crime and criminal behaviour and it is deemed significant, because for the first time we recognised that crime does not happen in a social vacuum. The objectives evolved, to introduce scepticism in the order of how systems work and to challenge established views.

Since then, and through a series of events nationally and internationally, criminology is forging a way of critical reflection of social realities and professional practices. We do not have to simply expect a society with less crime, but a society with more fairness and equality for all. The responsibilities of those in position of power and authority is not to use and abuse it in order to gain against public interest. Consider the current pandemic, and the mass losses of human life. If this was preventable, even in the slightest, is there negligence? If people were left unable to defend themselves is that criminal? Surely these are questions criminology asks and this is why regardless of the time and the circumstances there will always be time for criminology to raise these, and many more questions.

Criminology: in the business of creating misery?

I’ve been thinking about Criminology a great deal this summer! Nothing new you might say, given that my career revolves around the discipline. However, my thoughts and reading have focused on the term ‘criminology’ rather than individual studies around crime, criminals, criminal justice and victims. The history of the word itself, is complex, with attempts to identify etymology and attribute ownership, contested (cf. Wilson, 2015). This challenge, however, pales into insignificance, once you wander into the debates about what Criminology is and, by default, what criminology isn’t (cf. Cohen, 1988, Bosworth and Hoyle, 2011, Carlen, 2011, Daly, 2011).

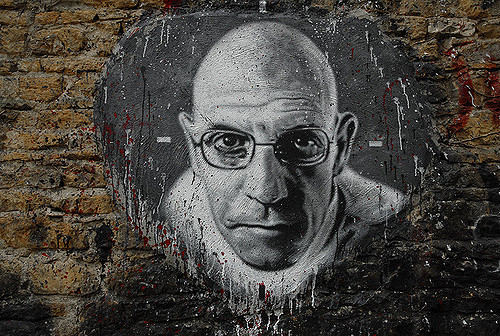

Foucault (1977) infamously described criminology as the embodiment of utilitarianism, suggesting that the discipline both enabled and perpetuated discipline and punishment. That, rather than critical and empathetic, criminology was only ever concerned with finding increasingly sophisticated ways of recording transgression and creating more efficient mechanisms for punishment and control. For a long time, I have resisted and tried to dismiss this description, from my understanding of criminology, perpetually searching for alternative and disruptive narratives, showing that the discipline can be far greater in its search for knowledge, than Foucault (1977) claimed.

However, it is becoming increasingly evident that Foucault (1977) was right; which begs the question how do we move away from this fixation with discipline and punishment? As a consequence, we could then focus on what criminology could be? From my perspective, criminology should be outspoken around what appears to be a culture of misery and suspicion. Instead of focusing on improving fraud detection for peddlers of misery (see the recent collapse of Wonga), or creating ever increasing bureaucracy to enable border control to jostle British citizens from the UK (see the recent Windrush scandal), or ways in which to excuse barbaric and violent processes against passive resistance (see case of Assistant Professor Duff), criminology should demand and inspire something far more profound. A discipline with social justice, civil liberties and human rights at its heart, would see these injustices for what they are, the creation of misery. It would identify, the increasing disproportionality of wealth in the UK and elsewhere and would see food banks, period poverty and homelessness as clearly criminal in intent and symptomatic of an unjust society.

Unless we can move past these law and order narratives and seek a criminology that is focused on making the world a better place, Foucault’s (1977) criticism must stand.

References

Bosworth, May and Hoyle, Carolyn, (2010), ‘What is Criminology? An Introduction’ in Mary Bosworth and Carolyn Hoyle, (2011), (eds), What is Criminology?, (Oxford: Oxford University Press): 1-12

Carlen, Pat, (2011), ‘Against Evangelism in Academic Criminology: For Criminology as a Scientific Art’ in Mary Bosworth and Carolyn Hoyle, (eds), What is Criminology?, (Oxford: Oxford University Press): 95-110

Cohen, Stanley, (1988), Against Criminology, (Oxford: Transaction Books)

Daly, Kathleen, (2011), ‘Shake It Up Baby: Practising Rock ‘n’ Roll Criminology’ in Mary Bosworth and Carolyn Hoyle, (eds), What is Criminology?, (Oxford: Oxford University Press): 111-24

Foucault, Michel, (1977), Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, tr. from the French by Alan Sheridan, (London: Penguin Books)

Wilson, Jeffrey R., (2015), ‘The Word Criminology: A Philology and a Definition,’ Criminology, Criminal Justice Law, & Society, 16, 3: 61-82

‘I read the news today, oh boy’

The English army had just won the war

The English army had just won the war

A crowd of people turned away

But I just had to look

Having read the book

(Lennon and McCartney, 1967),

The news these days, without fail, is terrible. Wherever you look you are confronted by misery, death, destruction and terror. Regular news channels and social media bombard us with increasingly horrific tales of people living and dying under tremendous pressure, both here in the UK and elsewhere in the world. Below are just a couple of examples drawn from the mainstream media over the space of a few days, each one an example of individual or collective misery. None of them are unique and they all made the headlines in the UK.

‘Deaths of UK homeless people more than double in five years’

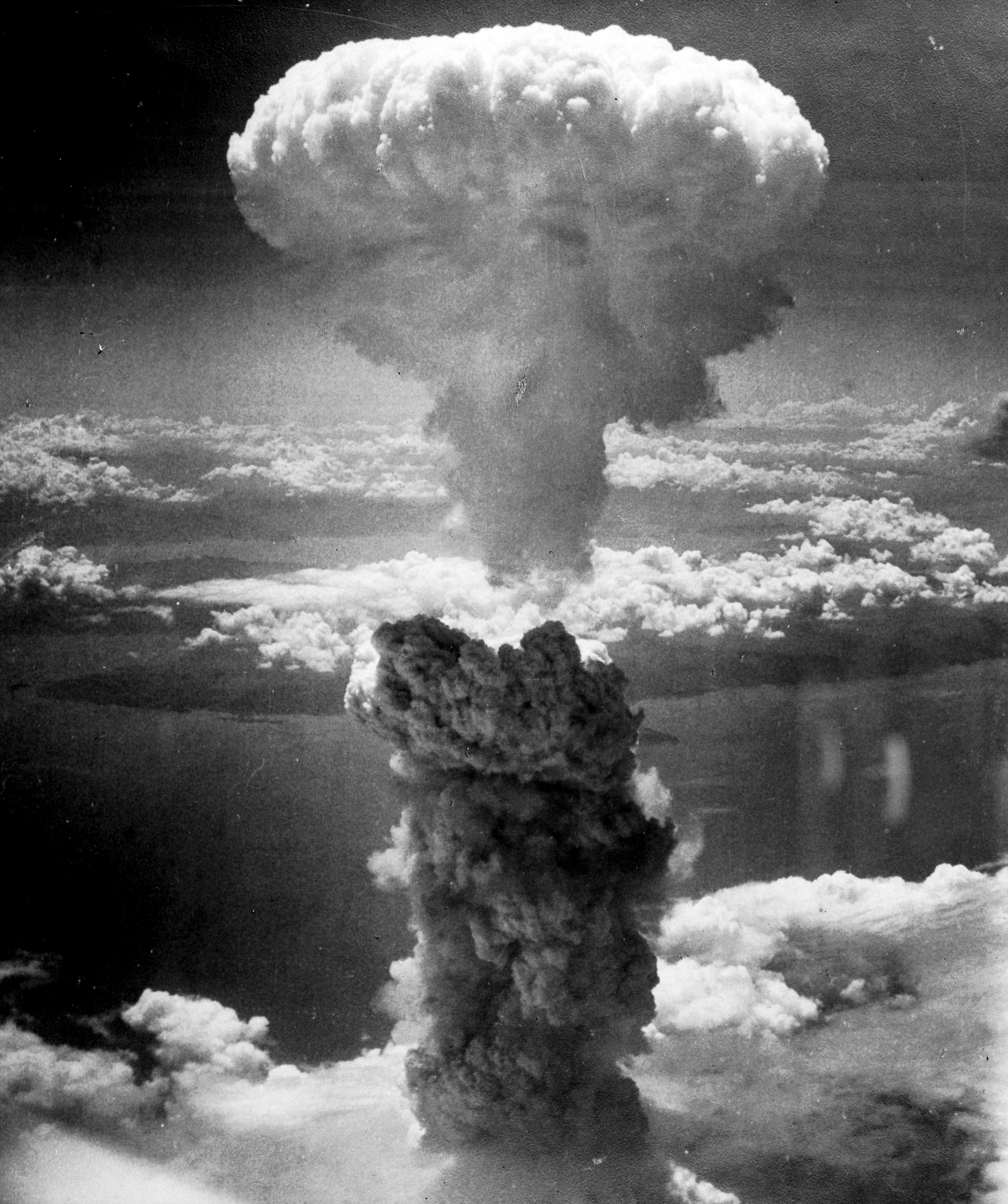

‘Syria: 500 Douma patients had chemical attack symptoms, reports say’

‘London 2018 BLOODBATH: Capital on a knife edge as killings SOAR to 56 in three months’

So how do we make sense of these tumultuous times? Do we turn our backs and pretend it has nothing to do with us? Can we, as Criminologists, ignore such events and say they are for other people to think about, discuss and resolve?

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, Stanley Cohen, posed a similar question; ‘How will we react to the atrocities and suffering that lie ahead?’ (2001: 287). Certainly his text States Of Denial: Knowing about Atrocities and Suffering makes clear that each of us has a part to play, firstly by ‘knowing’ that these things happen; in essence, bearing witness and acknowledging the harm inherent in such atrocities. But is this enough?

Cohen, persuasively argues, that our understanding has fundamentally changed:

The political changes of the last decade have radically altered how these issues are framed. The cold-war is over, ordinary “war” does not mean what it used to mean, nor do the terms “nationalism”, “socialism”, “welfare state”, “public order”, “security”, “victim”, “peace-keeping” and “intervention” (2001: 287).

With this in mind, shouldn’t our responses as a society, also have changed, adapted to these new discourses? I would argue, that there is very little evidence to show that this has happened; whilst problems are seemingly framed in different ways, society’s response continues to be overtly punitive. Certainly, the following responses are well rehearsed;

- “move the homeless on”

- “bomb Syria into submission”

- “increase stop and search”

- “longer/harsher prison sentences”

- “it’s your own fault for not having the correct papers?”

Of course, none of the above are new “solutions”. It is well documented throughout much of history, that moving social problems (or as we should acknowledge, people) along, just ensures that the situation continues, after all everyone needs somewhere just to be. Likewise, we have the recent experiences of invading Iraq and Afghanistan to show us (if we didn’t already know from Britain’s experiences during WWII) that you cannot bomb either people or states into submission. As criminologists, we know, only too well, the horrific impact of stop and search, incarceration and banishment and exile, on individuals, families and communities, but it seems, as a society, we do not learn from these experiences.

Yet if we were to imagine, those particular social problems in our own relationships, friendship groups, neighbourhoods and communities, would our responses be the same? Wouldn’t responses be more conciliatory, more empathetic, more helpful, more hopeful and more focused on solving problems, rather than exacerbating the situation?

Next time you read one of these news stories, ask yourself, if it was me or someone important to me that this was happening to, what would I do, how would I resolve the situation, would I be quite so punitive? Until then….

Whoever fights monsters should see to it that in the process he does not become a monster. And when you look long into an abyss, the abyss also looks into you (Nietzsche, 1886/2003: 146)

References:

Cohen, Stanley, (2001), States Of Denial: Knowing about Atrocities and Suffering, (Cambridge: Polity Press)

Lennon, John and McCartney, Paul, (1967), A Day in the Life, [LP]. Recorded by The Beatles in Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, EMI Studios: Parlaphone

Nietzsche, Friedrich, (1886/2003), Beyond Good and Evil: Prelude to a Philosophy of the Future, tr. from the German by R. J. Hollingdale, (London: Penguin Books)