Home » Social norms (Page 3)

Category Archives: Social norms

Things I used to could do without a phone. #BlackenAsiaWithLove

A Spoken Word poem for young people everywhere, esp Youth in Asia, who may never know WE LIVED before smartphones…and live to tell about it.

Walk.

Walk down the street.

Find my way.

Go someplace.

Go someplace I had previously been.

Go someplace I had previously not been.

Meet.

Meet friends.

Meet friends at a specific time and place.

Meet new people.

Meet new people without suspicion.

Strike up a conversation with a stranger.

Make myself known to a previously unknown person.

Now, everything and everyone unknown is literally described as ‘weird’.

Eat.

Eat in a restaurant by myself.

Pay attention to the waiter.

Wait for my order to arrive.

Sit.

Sit alone.

Sit with others.

Listen.

Listen to the sound of silence.

Listen to music.

Listen to a whole album.

Listen to the cityscape.

Overhear others’ conversations in public.

Watch kids play.

Shop.

Share.

Share pictures.

Take pictures.

Develop pictures.

Frame pictures.

See the same picture in the same spot.

Read.

Read a book.

Read a long article.

Read liner notes.

Pee.

I used to be able to stand at a urinal and focus on what I was doing,

Not feeling bored,

Not feeling the need to respond to anything that urgently.

Nothing could be so urgent that I could not, as the Brits say, ‘take a wee’.

Wait.

Wait at a traffic light.

Wait for a friend at a pre-determined place and time.

Wait for my turn.

Wait for a meal I ordered to arrive.

Wait in an office for my appointment.

Wait in line.

Wait for anything!

I used to appreciate the downtime of waiting.

Now waiting fuels FOMO.

I used to enjoy people watching…

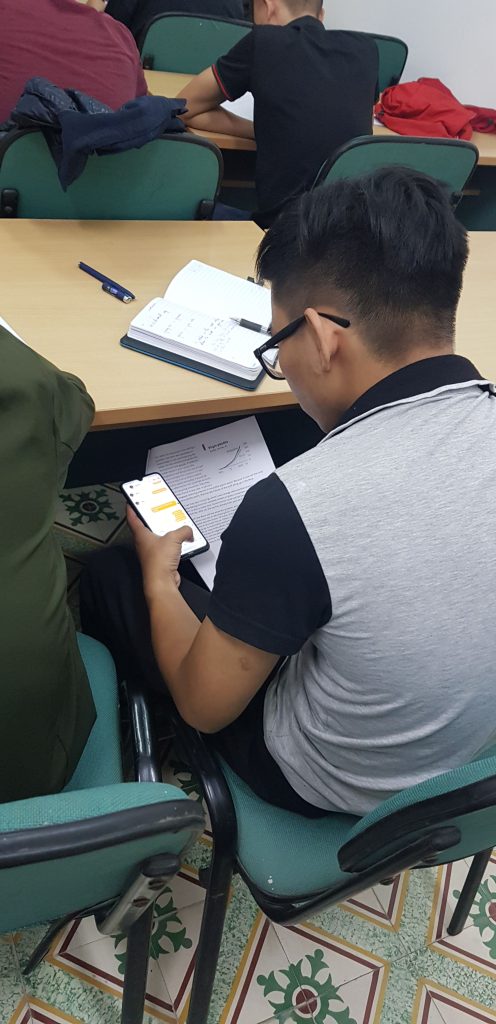

Now I just watch people on their phones.

It’s genuine anxiety.

Walk.

Walk from point A to B.

I used to could walk between two known points without having to mark the moment with a post.

Now I can’t walk down the hall,

Or through the house or even to the toilet without checking my phone.

I avoid eye contact with strangers.

Anyone I don’t already know is strange.

I used to could muscle through this awkwardness.

Talk.

Have a conversation.

A friend and I recently lamented about how you used to could have a conversation and

Even figure out a specific thing that you couldn’t immediately recall…

Just by talking.

I also appreciate the examples we discussed.

Say you wanted to mention a world leader but couldn’t immediately remember their name. What would you do before?

Rattle off the few facts you could recall and in so doing you’d jog your memory.

Who was the 43rd US president?

If you didn’t immediately recall his name,

You might have recalled that the current one is often called “45” since

Many folks avoid calling his name.

You know Obama was before him, therefore he must’ve been number “44.”

You know Obama inherited a crap economy and several unjust wars,

Including the cultural war against Islam. And

That this was even one of the coded racial slurs used against him: “A Muslim.”

Putting these facts together,

You’d quickly arrive at Dubya! And

His whole warmongering cabinet. And

Condi Rice. And

General Powell’s botched PowerPoint presentation at the UN. And

Big dick Cheney, Halliburton and that fool shooting his friend while hunting.

That whole process might have taken a full minute,

But so would pulling up 43’s name on the Google.

This way, however, you haven’t lost the flow of conversation nor the productive energy produced between two people when they talk.

(It’s called ‘limbic resonance’, BTW).

Yeah, I used to be able to recall things…

Many more things about the world without my mobile phone.

Wonder.

Allow my mind to wander.

Entertain myself with my own thoughts.

Think.

Think new things.

Think differently just by thinking through a topic.

I used to know things.

Know answers that weren’t presented to me as search results.

I used to trust my own knowledge.

I used to be able to be present, enjoying my own company,

Appreciating the wisdom that comes with the mental downtime.

Never the fear of missing out,

Allowing myself time to reflect.

It is in reflection that wisdom is born.

Now, most of us just spend our time simply doing:

Surfing, scrolling, liking, dissing, posting, sharing and the like.

Even on a wondrous occasion, many of us would rather be on our phones.

Not just sharing the wonderful occasion –

Watching an insanely beautiful landscape through our tiny screens,

Phubbing the people we’re actually with,

Reducing a wondrous experience to a well-crafted selfie –

But just making sure we’re not missing out on something rather mundane happening back home.

I used to could be in the world.

Now, I’m just in cyberspace.

I used to be wiser.

“Truth” at the age of uncertainty

Research methods taught for undergraduate students is like asking a young person to eat their greens; fraught with difficulties. The prospect of engaging with active research seems distant, and the philosophical concepts underneath it, seem convoluted and far too complex. After all, at some point each of us struggled with inductive/deductive reasoning, whilst appreciating the difference between epistemology over methodology…and don’t get me stated on the ontology and if it is socially proscribed or not…minefield. It is through time, and plenty of trial and error efforts, that a mechanism is developed to deliver complex information in any “palatable” format!

There are pedagogic arguments here, for and against, the development of disentangling theoretical conventions, especially to those who hear these concepts for the first time. I feel a sense of deep history when I ask students “to observe” much like Popper argued in The Logic of Scientific Discovery when he builds up the connection between theory and observational testing.

So, we try to come to terms with the conceptual challenges and piqued their understanding, only to be confronted with the way those concepts correlate to our understanding of reality. This ability to vocalise social reality and conditions around us, is paramount, on demonstrating our understanding of social scientific enquiry. This is quite a difficult process that we acquire slowly, painfully and possibly one of the reasons people find it frustrating. In observational reality, notwithstanding experimentation, the subjectivity of reality makes us nervous as to the contentions we are about to make.

A prime skill at higher education, among all of us who have read or are reading for a degree, is the ability to contextualise personal reality, utilising evidence logically and adapting them to theoretical conventions. In this vein, whether we are talking about the environment, social deprivation, government accountability and so on, the process upon which we explore them follows the same conventions of scholarship and investigation. The arguments constructed are evidence based and focused on the subject rather than the feelings we have on each matter.

This is a position, academics contemplate when talking to an academic audience and then must transfer the same position in conversation or when talking to a lay audience. The language may change ever so slightly, and we are mindful of the jargon that we may use but ultimately we represent the case for whatever issue, using the same processes, regardless of the audience.

Academic opinion is not merely an expert opinion, it is a viewpoint, that if done following all academic conventions, should represent factual knowledge, up to date, with a degree of accuracy. This is not a matter of opinion; it is a way of practice. Which makes non-academic rebuttals problematic. The current prevailing approach is to present everything as a matter of opinion, where each position is presented equally, regardless of the preparation, authority or knowledge embedded to each. This balanced social approach has been exasperated with the onset of social media and the way we consume information. The problem is when an academic who presents a theoretical model is confronted with an opinion that lacks knowledge or evidence. The age-old problem of conflating knowledge with information.

This is aggravated when a climatologist is confronted by a climate change denier, a criminologist is faced with a law and order enthusiast (reminiscing the good-old days) or an economist presenting the argument for remain, shouted down by a journalist with little knowledge of finance. We are at an interesting crossroad, after all the facts and figures at our fingertips, it seems the argument goes to whoever shouts the loudest.

Popper K., (1959/2002), The Logic of Scientific Discovery, tr. from the German Routledge, London