Home » Social movements

Category Archives: Social movements

25 years of Criminology

When the world was bracing for a technological winter thanks to the “millennium bug” the University of Northampton was setting up a degree in Criminology. Twenty-five years later and we are reflecting on a quarter of a century. Since then, there have been changes in the discipline, socio-economic changes and wider changes in education and academia.

The world at the beginning of the 21st century in the Western hemisphere was a hopeful one. There were financial targets that indicated a raising level of income at the time and a general feeling of a new golden age. This, of course, was just before a new international chapter with the “war on terror”. Whilst the US and its allies declared the “war on terror” decreeing the “axis of evil”, in Criminology we offered the module “Transnational Crime” talking about the challenges of international justice and victor’s law.

Early in the 21st century it became apparent that individual rights would take centre stage. The political establishment in the UK was leaving behind discussions on class and class struggles and instead focusing on the way people self-identify. This ideological process meant that more Western hemisphere countries started to introduce legal and social mechanisms of equality. In 2004 the UK voted for civil partnerships and in Criminology we were discussing group rights and the criminalisation of otherness in “Outsiders”.

During that time there was a burgeoning of academic and disciplinary reflection on the way people relate to different identities. This started out as a wider debate on uniqueness and social identities. Criminology’s first cousin Sociology has long focused on matters of race and gender in social discourse and of course, Criminology has long explored these social constructions in relation to crime, victimisation and social precipitation. As a way of exploring race and gender and age we offered modules such as “Crime: Perspectives of Race and Gender” and “Youth, Crime and the Media”. Since then we have embraced Kimberlé Crenshaw’s concept of intersectionality and embarked on a long journey for Criminology to adopt the term and explore crime trends through an increasingly intersectional lens. Increasingly our modules have included an intersectional perspective, allowing students to consider identities more widely.

The world’s confidence fell apart when in 2008 in the US and the UK financial institutions like banks and other financial companies started collapsing. The boom years were replaced by the bust of the international markets, bringing upheaval, instability and a lot of uncertainty. Austerity became an issue that concerned the world of Criminology. In previous times of financial uncertainty crime spiked and there was an expectation that this will be the same once again. Colleagues like Stephen Box in the past explored the correlation of unemployment to crime. A view that has been contested since. Despite the statistical information about declining crime trends, colleagues like Justin Kotzé question the validity of such decline. Such debates demonstrate the importance of research methods, data and critical analysis as keys to formulating and contextualising a discipline like Criminology. The development of “Applied Criminological Research” and “Doing Research in Criminology” became modular vehicles for those studying Criminology to make the most of it.

During the recession, the reduction of social services and social support, including financial aid to economically vulnerable groups began “to bite”! Criminological discourse started conceptualising the lack of social support as a mechanism for understanding institutional and structural violence. In Criminology modules we started exploring this and other forms of violence. Increasingly we turned our focus to understanding institutional violence and our students began to explore very different forms of criminality which previously they may not have considered. Violence as a mechanism of oppression became part of our curriculum adding to the way Criminology explores social conditions as a driver for criminality and victimisation.

While the world was watching the unfolding of the “Arab Spring” in 2011, people started questioning the way we see and read and interpret news stories. Round about that time in Criminology we wanted to break the “myths on crime” and explore the way we tell crime stories. This is when we introduced “True Crimes and Other Fictions”, as a way of allowing students and staff to explore current affairs through a criminological lens.

Obviously, the way that the uprising in the Arab world took charge made the entire planet participants, whether active or passive, with everyone experiencing a global “bystander effect”. From the comfort of our homes, we observed regimes coming to an end, communities being torn apart and waves of refugees fleeing. These issues made our team to reflect further on the need to address these social conditions. Increasingly, modules became aware of the social commentary which provides up-to-date examples as mechanism for exploring Criminology.

In 2019 announcements began to filter, originally from China, about a new virus that forced people to stay home. A few months later and the entire planet went into lockdown. As the world went into isolation the Criminology team was making plans of virtual delivery and trying to find ways to allow students to conduct research online. The pandemic rendered visible the substantial inequalities present in our everyday lives, in a way that had not been seen before. It also made staff and students reflect upon their own vulnerabilities and the need to create online communities. The dissertation and placement modules also forced us to think about research outside the classroom and more importantly outside the box!

More recently, wars in Europe, the Middle East, Africa and Asia have brought to the forefront many long posed questions about peace and the state of international community. The divides between different geopolitical camps brought back memories of conflicts from the 20th century. Noting that the language used is so old, but continues to evoke familiar divisions of the past, bringing them into the future. In Criminology we continue to explore the skills required to re-imagine the world and to consider how the discipline is going to shape our understanding about crime.

It is interesting to reflect that 25 years ago the world was terrified about technology. A quarter of a century later, the world, whilst embracing the internet, is worriedly debating the emergence of AI, the ethics of using information and the difference between knowledge and communication exchanges. Social media have shifted the focus on traditional news outlets, and increasingly “fake news” is becoming a concern. Criminology as a discipline, has also changed and matured. More focus on intersectional criminological perspectives, race, gender, sexuality mean that cultural differences and social transitions are still significant perspectives in the discipline. Criminology is also exploring new challenges and social concerns that are currently emerging around people’s movements, the future of institutions and the nature of society in a global world.

Whatever the direction taken, Criminology still shines a light on complex social issues and helps to promote very important discussions that are really needed. I can be simply celebratory and raise a glass in celebration of the 25 years and in anticipation of the next 25, but I am going to be more creative and say…

To our students, you are part of a discipline that has a lot to say about the world; to our alumni you are an integral part of the history of this journey. To those who will be joining us in the future, be prepared to explore some interesting content and go on an academic journey that will challenge your perceptions and perspectives. Radical Criminology as a concept emerged post-civil rights movements at the second part of the 20th century. People in the Western hemisphere were embracing social movements trying to challenge the established views and change the world. This is when Criminology went through its adolescence and entered adulthood, setting a tone that is both clear and distinct in the Social Sciences. The embrace of being a critical friend to these institutions sitting on crime and justice, law and order has increasingly become fractious with established institutions of oppression (think of appeals to defund the police and prison abolition, both staples within criminological discourse. The rigour of the discipline has not ceased since, and these radical thoughts have led the way to new forms of critical Criminology which still permeate the disciplinary appeal. In recent discourse we have been talking about radicalisation (which despite what the media may have you believe, can often be a positive impetus for change), so here’s to 25 more years of radical criminological thinking! As a discipline, Criminology is becoming incredibly important in setting the ethical and professional boundaries of the future. And don’t forget in Criminology everyone is welcome!

Realtopia?

I have recently been reading and re-reading about all things utopic, dystopic and “real[life]topic” for new module preparations; Imagining Crime. Dystopic societies are absolutely terrifying and whilst utopic ideas can envision perfect-like societies these utopic worlds can also become terrifying. These ‘imagined nowhere’ places can also reflect our lived realities, take Nazism for an example.

In CRI1009 Imagining Crime, students have already began to provide some insightful criticism of the modern social world. Questions which have been considered relate to the increasing use of the World Wide Web and new technologies. Whilst these may be promoted as being utopic, i.e., incredibly advanced and innovative, these utopic technological ideas also make me dystopic[ly] worry about the impact on human relations.

In the documentary America’s New Female Right there are examples of families who are also shown to be using technology to further a far right utopic agenda. An example includes a parent that is offended because their child’s two favourite teachers were (described as being) ‘homosexuals’, the parents response to this appeared to be taking the child out of school to home school the child instead, but also to give their child an iPad/tablet screen to use as a replacement for the teachers. Another example consisted of a teen using social media to spread far right propaganda and organise a transphobic rally. In the UK quite recently the far right riots were organised and encouraged via online platforms.

I would not advise watching the documentary, aside from being terrifying, the report and their team did very little to challenge these ideas. I did get the sense that the documentary was made to satisfy voyeuristic tendencies, and as well as this, it seems to add to the mythical idea that far right ideology and actions only exists within self identified far right extremist groups when this is not the case.

Mills (1959) suggests that people feel troubled if the society in which they live in has wide scale social problems. So might the unquestioning and increased use of technologies add to troubles due to the spreading of hate and division? And might this have an impact on our ability to speak to and challenge each other? Or to learn about lives different to our own? This reminds me of Benjamin Zephaniah’s children’s book titled People Need People (2022), maybe technologies and use of the internet are both connecting yet removing us from people in some way.

References

Mills, C. W. (2000) The Sociological Imagination. Fortieth anniversary edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Zephaniah, B. (2022) People Need People. (London: Orchard Books)

Doing the right thing

It seems that very often, the problem with politics in this country is that it gets in the way of doing the right thing. Despite the introduction of the The Seven Principles of Public Life known as the Nolan Principles, politicians (not all of them of course, but you will have seen ample examples) still seem to be hell bent on scoring political advantage, obfuscating on matters of principle and where possible avoiding real leadership when the country is crying out for it. Instead, they look to find someone, anyone, else to blame for failures that can only be described as laying clearly at the door of government and at times the wider institution of parliament.

One example you may recall was the complete farce in parliament where the speaker, Sir Lyndsay Hoyle, was berated for political interference and breaking the rules of the house prior to a debate about a ceasefire in Gaza. It became quite obvious to anyone on the outside that various political parties, Conservatives, Labour and the Scottish National Party were all in it to score points. The upshot, rather than the headlines being about a demand for a ceasefire in Gaza, the headlines were about political nonsense, even suggesting that the very core of our democracy was at stake. Somehow, they all lost sight of what was important, the crises, and it really is still a crisis, in Gaza. Doing the right thing was clearly not on their minds, morals and principles were lost along the way in the thrust for the best political posturing.

And then we come to the latest saga involving political parties, the WASPI women (Women Against State Pension Inequality) campaign. The report from the Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman has ruled that the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) “failed to provide accurate, adequate and timely information” about changes to pension ages for women. The report makes interesting reading. In essence, it accuses the DWP of maladministration on several counts.

The Pensions Act 1995 changed the way in which women could draw their pensions in an effort to equalise the age with men. A timetable was drawn up raising the qualifying age for women from 60 to 65, with the change phased in between 2010 and 2020. However, under the Pensions Act 2011, the new qualifying age of 65 for women was brought forward to 2018. The report acknowledges that the DWP carried out campaigns from 1995 onwards but in 2004 received results of research that a considerable number of affected women still believed that their retiring age was 60. Unfortunately, through prevarication and for some quite inexplicable reasoning the women affected were not notified or were notified far too late. There was a calculation carried out that suggested some women were not told until 18 months before their intended retirement date. The matter was taken before the courts but the courts ruling did nothing to resolve the issue other than providing a ruling that the DWP were not required by law to notify the women.

You can read about the debacle anywhere on the Internet and the WASPI women have their own Facebook page. What seems astounding is that both the Government and the opposition have steadfastly avoided being drawn on the matter of compensation for these women. I should add that the maladministration has had serious detrimental impacts on many of them. Not even a sorry, we got it wrong. Instead we see articles written by right wing Conservatives suggesting the women had been provided with ample warning. If you read the report, it makes it clear that provisions under the Civil Service Code were not complied with. It is maladministration and it took place under a number of different governments.

Not getting it right in the first instance was compounded by not getting it right several times over later on. It seems that given the likely cost to the taxpayer, this maladministration is likely, like so many other cock ups by government and its agencies, to be kicked into the long grass. Doing the right thing is a very long, long way away in British politics. And lets not forget the Post Office scandal, the infected blood transfusion scandal and the Windrush scandal to name but a few. So little accountability, such cost to those impacted.

- The quotation in the image is often wrongly misattributed to C. S. Lewis. ↩︎

Is the cost of living crisis just state inflicted violence

Back in November 2022, social media influencer Lydia Millen was seen to spark controversy on the popular app ‘TikTok’ when she claimed that her heating was broken, so she therefore was going to check into the Savoy in London.

Her video, which she filmed whilst wearing an outfit worth over £30,000, sparked outrage on the app and across popular social media platforms. People began to argue that her comment was not well received in our current social climate, where people have to choose whether they should spend money on heating or groceries. For many, no matter your financial situation, problems with heating rarely resorts in a luxury stay in London.

With pressure mounting, Lydia decided to reply to comments on her video. When one individual stated “My heating is off because I can’t afford to put it on”, Lydia replied “It’s honestly heart breaking I just hope you know that other people’s realities can be different and that’s not wrong”. Sorry, Lydia; it is wrong. Realities are not different; they are miles apart. This is clearly seen in the fact that the National Institute of Economic and Social Research estimate that 1.5 million households in the UK over the next year will be landed in poverty (NIESR, 2022).

Ultimately, this is a social issue. Like Lydia said, in a society in which individuals are stratified based on their economic, cultural and social capital, we are conditioned to believe that this is just the way it is, and therefore, it is not wrong that other people have different realities. However, for me, it is not ‘different realities’, it is a matter of being able to eat and be warm versus being able to stay in a luxury hotel in London.

So, why is this a criminological issue? The cost of living crisis is simply just state inflicted poverty. Alike to Lydia with her social following, the government have the power to make change and use their position in society to remedy cost of living issues, but they don’t. This is not a mark of their failure as a government, it is a mark of their success. You only have to look at the government’s complete denial surrounding social issues to realise that this was their plan all along, and the longer this denial continues, the longer they succeed. This is seen in the case of Lydia Millen, who has acted as a metaphor for the level of negligence in which the government exercises over its citizens. Ultimately, for Lydia, it is very easy to tuck yourself into a luxury bed in the Savoy and close the curtains on the real world. The people affected by the crisis are not people like Lydia Millen, they are everyday people who work 40+ hours a week, and still cannot make ends meet. For the government, the cost of living crisis is the perfect way to separate the wheat from the chaff.

Ultimately, the cost of living crisis is not too dissimilar to the strikes that the UK is currently experiencing. Alike to the strikes, the cost of living crisis was always going to happen at the hands of a negligent government. The only way we can begin to address this problem is by giving our support, by supporting strikes all across the country, and by standing up for what is right. After all, the powers in our country have shown that our needs as a society are not a priority, so it is time to support ourselves.

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” ― Martin Luther King Jr.

References:

National Institute of Economic and Social Research (2022) What Can Be Done About the Cost-of-Living Crisis? NIESR [online]. Available from: https://www.niesr.ac.uk/blog/what-can-be-done-about-the-cost-of-living-crisis [Accessed 23/01/23].

A race to the bottom

Happy new year to one and all, although I suspect for many it will be a new year of trepidation rather than hope and excitement.

It seems that every way we turn there is a strike or a threat of a strike in this country, reminiscent, according to the media, of the 1970s. It also seems that every public service we think about (I mean this in the wider context so would include Royal Mail for example,) is failing in one way or another. The one thing that strikes me though, pardon the pun, is that none of this has suddenly happened. And yet, if you were to believe media reporting, this is something that is caused by those pesky unions and intransigent workers or is it the other way round? Anyway, the constant rhetoric of there is ‘no money’, if said often enough by politicians and echoed by media pundits becomes the lingua franca. Watch the news and you will see those ordinary members of the public saying the same thing. They may prefix this with ‘I understand why they are striking’ and then add…’but there is no money’.

When I listen to the radio or watch the news on television (a bit outdated I know), I am incensed by questions aimed at representatives of the railway unions or the nurses’ union, amongst others, along the lines of ‘what have you got to say to those businesses that are losing money as a result of your strikes or what would you like to say to patients that have yet again had their operations cancelled’? This is usually coupled with an interview of a suffering business owner or potential patient. I know what I would like to say to the ignorant idiot that asked the question and I’m sure most of you, especially those that know me, know what that is. Ignorant, because they have ignored the core and complex issues, wittingly or unwittingly, and an idiot because you already know the answer to the question but also know the power of the media. Unbiased, my ….

When we look at all the different services, we see that there is one thing in common, a continuous, often political ideologically uncompromising drive to reduce real time funding for public services. As much as politicians will argue about the amount of money ploughed into the services, they know that the funding has been woefully inadequate over the years. I don’t blame the current government for this, it is a succession of governments and I’m afraid Labour laying the blame at the Tory governments’ door just won’t wash. Social care, for example, has been constantly ignored or prevaricated over, long before the current Tories came to power, and the inability of social care to respond to current needs has a significant knock-on effect to health care. I do however think the present government is intransigent in failing to address the issues that have caused the strikes. Let us be clear though, this is not just about pay as many in government and the media would have you believe. I’m sure, if it was, many would, as one rather despicable individual interviewed on the radio stated, ‘suck it up and get on with it’. I have to add, I nearly crashed the car when I heard that, and the air turned blue. Another ignoramus I’m afraid.

Speak to most workers and they will tell you it is more about conditions rather than pay per se. Unfortunately, those increasingly unbearable and unworkable conditions have been caused by a lack of funding, budget restraints and pay restraints. We now have a situation where people don’t want to work in such conditions and are voting with their feet, exacerbating the conditions. People don’t want to join those services because of poor pay coupled with unworkable conditions. The government’s answer, well to the nurses anyway, is that they are abiding by the independent pay review body. That’s like putting two fingers up to the nurses, the health service and the public. When I was in policing it had an independent pay review body, the government didn’t always abide by it, notably, they sometimes opted to award less than was recommended. The word recommendation only seems to work in favour of government. Now look at the police service, underfunded, in chaos and failing to meet the increasing demands. Some of those demands caused by an underfunded social and health care service, particularly mental health care.

Over the years it has become clear that successive governments’ policies of waste, wasted opportunity, poor decision making, vote chasing, and corruption have led us to where we are now. The difference between first and third world country governments seems to only be a matter of degree of ineptitude. It has been a race to the bottom, a race to provide cheap, inadequate services to those that can’t afford any better and a race to suck everyone other than the rich into the abyss.

A government minister was quoted as saying that by paying wage increases it would cost the average household a thousand pound a year. I’d pay an extra thousand pound, in fact I’d pay two if it would allow me to see my doctor in a timely manner, if it gave me confidence that the ambulance would turn up promptly when needed, if it meant a trip to A&E wouldn’t involve a whole day’s wait or being turned away or if I could get to see a dentist rather than having to attempt DIY dentistry in desperation. I’d like to think the police would turn up promptly when needed and that my post and parcels would be delivered on time by someone that had the time to say hello rather than rushing off because they are on an unforgiving clock (particularly pertinent for elderly and vulnerable people).

And I’m not poor but like so many people I look at the new year with trepidation. I don’t blame the strikers; they just want to improve their conditions and vis a vis our conditions. Blaming them is like blaming cows for global warming, its nonsensical.

And as a footnote, I wonder why we never hear about our ex-prime minister Liz Truss and her erstwhile Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng; what a fine mess they caused. But yesterday’s news is no news and yet it is yesterday’s news that got us to where we are now. Maybe the media could report on that, although I suspect they probably won’t.

I am not your “ally” (or am I?)

Today’s blog entry is a stream of consciousness rather than a finished entry with an introduction, middle and conclusion. It’s something that has been puzzling me for sometime, trying to work out why the term “ally” discomforts me and yet, not really coming to a firm conclusion. So I thought I’d explore it through a blog entry and would welcome anyone’s input to help me clarify and refine my own thinking and either embrace or reject the term.

Anyone that knows me, knows I love reading and of course, I love words. I love to play with them, say them, write them, discover new ones and trace the etymology as far as I can. Equally, I do not hide the fact that I try to understand the world through both pacifism and feminism. This makes me rather susceptible to interrogating and challenging the things that I see around me, including the written and spoken word.

The most obvious place to start when exploring words, is a dictionary, and this blog entry does similar. According to the Cambridge English Dictionary the term “ally” has three distinct definitions:

“a country that has agreed officially to give help and support to another one, especially during a war”

“someone who helps and supports someone else”

“someone who helps and supports other people who are part of a group that is treated badly or unfairly, although they are not themselves a member of this group”

Now for obvious reasons, I find the first definition problematic, put simply for me, war is a crime. The act of waging war includes multiple violences, some individual, some institutional, some structural and all incredibly harmful decades, or even centuries later. Definitions which have roots in the military and warfare leave me cold and I hate the way in which they infiltrate civilian discourse. For example “the war on drugs”, “the war on poverty”, “officer to the meeting” and the reshaping of the term “ally” for the twenty-first century” I definitely don’t want to be the “ally” described in that definition.

Definition two is also problematic, albeit for different reasons. This definition seems far too broad, if I hold the door open for you, is that me being an ally? If I help you carry your heavy bags, can I say I’m your ally? This seems a nonsensical way to talk about everyday actions which would be better described as common civility, helping each other along the way.Should I say “thank you kind ally” every time, someone moves out of my way, or offers their seat on the bus? It seems evident that this definition does not help me explore my reservations.

The third definition appears to come closest to modern usage of the term “ally”. This term can be applied to many different groups (as can be seen from the badges below and these are just some of the many examples). “whilst I identify as cisgender, I’m a trans ally”, whilst currently heterosexual, I’m a LGBTQ+ ally”, despite being white, I’m a BLM ally” and so on. On the surface this is very positive, moving society away from the nonsense of people describing themselves as “colour-blind”, “gender-blind” or such trite phrases as “we all bleed the same”, ignoring the lack of equity in society and pretending that everyone has the same lived experience, the same opportunities, the same health, wealth and happiness. Buying into the hackneyed idea that if only you work hard enough, you will succeed, that we live in a classless society and the only thing holding anyone back is their own inertia.

However, maybe my problem isn’t with the word “ally” but the word “I”, and the fact that the two words seem inseparable, After all who decides who is an ally or who is not, is there a organisation somewhere that checks your eligibility to be an ally? I’m pretty sure there’s not which means that that “ally” is a description you apply to yourself. After all you can buy the badge, the t-shirt, the mug etc etc, capitalism is on your side, provided the tills are ringing, there’s every reason to sign up. Maybe a tiny percentage of your purchases goes to financially benefit the people you aim to support, for example the heavily criticised Skittles Pride campaign which donated only 2p to LGBTQ+ charities (and stands accused of white supremacy and racism). Of course, once you have bought the paraphernalia, there is no need to do anything else, beyond carrying/wearing/eating your “ally” goods with pride.

All of the above seems to marketise and weaponise behaviour that should be standard practice, good manners if you like, in a society. Do we need a special word for this kind of behaviour or should we strive to make sure we make space for everyone in our society? If individuals or groups gain civil rights, I don’t lose anything, I gain a growing confidence that the society in which I live is improving, that there is some movement (however small) toward equity for all. Societies should not make life more difficult for the people who live in them, regardless of religious or spiritual belief, we have one opportunity to make a good life for ourselves and others and that’s right now, so why seek to dehumanise and disadvantage other humans who are on the same journey as we are.

Ultimately, my main concern with the use of term of “ally” is that it obscures incredibly challenging social harms, with colour and symbols hiding inaction and apathy. Accept the label of “ally”, wear the badge, if you think it has meaning, but if you do nothing else, this is meaningless. if you see inequality and you do not call it out, take action to remedy the situation, the word “ally” means nothing other than an opportunity to make yourself central to the discussion, taking up, rather than making, room for those focused on making a more just society.

I still remain uncomfortable with the term “ally” and I doubt it will ever appear in my lexicon, but it’s worth remembering that an antonym of ally is enemy and nobody needs those.

ASUU vs The Federal Government

It will be 8 months in October since University Lecturers in Nigeria have embarked on a nationwide strike without adequate intervention from the government. It is quite shocking that a government will sit in power and cease to reasonably address a serious dispute such as this at such a crucial time in the country.

As we have seen over the years, strike actions in Nigerian Universities constitute an age-long problem and its recurring nature unmasks, quite simply, how the political class has refused to prioritise the knowledge-based economy.

In February 2022, the Academic Staff Union of Universities (ASUU) leadership

(which is the national union body that represents Nigerian University Lecturers during disputes) issued a 4-week warning strike to the Nigerian government due to issues of funding of the public Universities. Currently, the striking University Lecturers are accusing the government of failing to revitalise the dilapidated state of Nigerian Universities, they claim that the government has refused to implement an accountability system called UTAS and that representatives of the government have continued to backtrack on their agreement to adequately fund the Universities.

The government on the other hand is claiming that they have tried their best in negotiating with the striking lecturers – but that the lecturers are simply being unnecessarily difficult. Since 2017, several committees have been established to scrutinize the demands and negotiate with ASUU, but the inability of these committees to resolve these issues has led to this 8-month-long closure of Nigerian Universities. While this strike has generated multiple reactions from different quarters, the question to be asked is – who is to be blamed? Should the striking lecturers be blamed for demanding a viable environment for the students or should we be blaming the government for the failure of efforts to resolve this national embarrassment?

Of course, we can all understand that one of the reasons why the political class is often slow to react to these strike actions is because their children and families do not attend these schools. You either find them in private Universities in Nigeria or Universities abroad – just the same way they end up traveling abroad for medical check-ups. In fact, the problems being faced in the educational sector are quite similar to those found within the Nigerian health sector – where many doctors are already emigrating from the country to countries that appreciate the importance of medical practitioners and practice. So, what we find invariably is a situation where the children of the rich continue to enjoy uninterrupted education, while the children of the underprivileged end up spending 7 years on a full-time 4-year program, due to the failure of efforts to preserve the educational standards of Nigerian institutions.

In times like these, I remember the popular saying that when two elephants fight, it’s the grass that suffers. The elephants in this context are both the federal government and the striking lecturers, while those suffering the consequences of the power contest are the students. The striking lecturers have not been paid their salaries for more than 5 months, and they are refusing to back down. On the other hand, the government seems to be suggesting that when they are “tired”, they will call off the strike. I am not sure that strike actions of the UK UCU will last this long before some sort of agreement would have been arranged. Again, my heart goes out to the Nigerian students during these hard times – because it is just unimaginable what they will be going through during these moments of idleness. And we must never forget that if care is not taken, the idle hand will eventually become the devil’s workshop!

Having said this, Nigerian Universities must learn from this event and adopt approaches through which they can generate their income. I am not inferring that they do not, but they just need to do more. This could be through ensuring large-scale investment programs, testing local/peculiar practices at the international level, tapping into research grant schemes, remodeling the system of tuition fees, and demonstrating a stronger presence within the African markets. As a general principle, any institution that wishes to reap the dividends of the knowledge-based economy must ensure that self-generated revenues should be higher than the government’s grants – and not the other way. So, Universities in Nigeria must strive to be autonomous in their engagements and their organisational structure – while maintaining an apolitical stance at all times.

While I agree that all of these can be difficult to achieve (considering the socio-political dynamics of Nigeria), Universities must remember that the continuous dependence on the government for funds will only continue to subject them to such embarrassments rather than being seen as respected intellectuals in the society. Again, Nigerian Universities need a total disruption; there is a need for a total overhaul of the system and a complete reform of the organisational structure and policies.

World Mental Health Day 2022

Monday marked World Mental Health day, that one day of the year when corporations and establishments which act like corporations tell us how much mental health matters to them, how their worker’s wellbeing matters to them. Given many sectors are affected by industrial action, or balloting for industrial action, this seems like a contradiction. Could it be possible that these industries and government are causing mental ill health, while paying lip service as a PR tool? Could it be that capitalism and inequalities associated with it are both the cause of mental health conditions and the very thing that prevents recovery from it?

Capitalism, I argue, is the root of a lot of society’s problems. The climate crisis is largely caused by consumerism and our innate need for stuff. The cost of living crisis is more like a greed crisis, since the rich are getting richer and the corporations are making phenomenal profits while small business struggle to make ends meet and what used to be the middle class are relying on food banks, getting second jobs and wondering whether they can afford to put the heating on. No wonder swathes of us are suffering with anxiety, depression and other mental health conditions. Of course, I cannot argue that capitalism is to blame for all manner of mental health conditions as that is simply not the case. There are many causes of mental health conditions which simply cannot be blamed on the environment. The mental health conditions I discuss here are the depression and anxiety that so many of us suffer as a result of environmental stressors, namely capitalist embedded society.

The mental health epidemic did not start with the current ‘crises’[1] though. Yes, the COVID-19 pandemic contributes and exacerbates already existing inequalities and the UK saw an increase in adults reporting psychological distress during the first two years of the pandemic, yet fewer were being diagnosed, perhaps due to inaccessibility of GPs during this time. Even before all these things which have exacerbated mental health conditions, prevalence of common mental disorders has been increasing since the 1990s. At the same time, we have seen in the UK, neoliberal ideology and austerity politics privatise parts of the NHS and decimate funding to services which support those with needs relating to their mental health.

I am not a psychologist but I know a problem when I see or experience one. Several months ago, I was feeling a bit low and anxious so I sought help from the local NHS talking therapies service. The service was still in restrictions and I was offered a series of six DBT-based telephone appointments. After the first appointment, I realised that this was not going to help. It was suggested to have a structure in my life. I have a job, doctoral studies, dog, home educated teenager, and I go to the gym. Scheduling and structure was already an essential part of my life. Next, I was taught coping skills. ‘Get some exercise’, ‘go for a walk’. Ditto previous session – I’m gym obsessed, with a dog I walk every day, mostly in green spaces. My coping skills were not the problem either. What I realised was that I didn’t need psychological help, I needed my environment to change. I needed my workload to be reduced, my PhD to finally end, my teenage daughter not to have any teenage problems, my dog to behave, for someone to pay my mortgage off, and a DIY fairy to fix the house I don’t have time to fix. No amount of therapy could ever change these things. I realised that it wasn’t me that was the problem – it was the world around me.

I am not alone. The Mental Health Foundation have published some disturbing statistics:

- In the past year, 74% of people (in a YouGov survey of 4,619) have felt so stressed they have been overwhelmed or unable to cope.

- Of those who reported feeling stressed in the past year, 22% cited debt as a stressor.

- Housing worries are a key source of stress for younger people (32% of 18-24-year-olds cited it as a source of stress in the past year). This is less so for older people (22% for 45-54-year-olds and just 7% for over 55s).

The data show not only the magnitude of the problem, but they also indicate some of the prevalent stressors in these respondents’ lives. Over 1 in 5 people cited debt as a stressor, and this survey was undertaken long before the cost of greed crisis. It is deeply concerning, particularly considering the anticipated increase in interest rates and the cost of energy bills at the moment.

The survey also showed that young people are concerned about housing, and this will have a disproportionate impact on care leavers who may not have family to support them and working class young people who cannot afford housing.

The causes of both these issues are predominantly fat cat employers who can afford to pay sufficient and fair wages, fat cat landlords buying up property in droves to rent them out at a huge profit, not to mention the fat cat energy suppliers making billions when half the country is now in fuel poverty. All the while, our capitalism loving government plays the game, shorting the pound to raise profits for their pals while the rest of us struggle to pay our mortgages after the Bank of England raised interest rates. No wonder we’re so stressed!

For work-related stress, anxiety and depression, the Labour Force Survey finds levels at the highest in this century, with 822,000 suffering from such mental health conditions. The Health and Safety Executive show that education and human, health and social work are the industries with the highest prevalence of stress, anxiety and depression. It is yet another symptom of neoliberalism which applies corporate values to education and public services, where students are the cash cow, and workers are exploited; and health and social work being under funded for years. Is it any wonder then that both nurses and lecturers are balloting for industrial action right now?

Despite all this, when World Mental Health Day arrives, it becomes the perfect PR exercise to pay lip service to staff wellbeing. The rail industry are in a period of industrial action, yet I have seen posts on rail companies’ social media promoting World Mental Health Day. Does the promotion of mental health initiatives include fair pay and conditions for staff? I think not.

Something needs to give, but what?

As a union member and representative, I argue for the need for employers to pay staff appropriately for the work they do, and to treat them fairly. This would at least address work and finance related stressors. Sanah Ahsan argues for a universal basic income, for safe and affordable housing and for radical change in the structural inequalities in the UK. Perhaps we could start with addressing structural inequalities. Gender, race and class all impact on mental health, with women more likely to be diagnosed with depression, Black women at an increased risk of common mental health disorders and the poor all more likely to suffer mental health conditions yet less likely to receive adequate and culturally appropriate support. In my research with women seeking asylum, there is a high prevalence of PTSD, yet therapy is difficult to access, in part due to language difficulties but also due to cultural differences. Structural inequalities then not only contribute to harm to marginalised people’s mental health, but also form a barrier to support.

I do not have a realistic solution, but I have the feeling society needs a radical social change. We need an end to structural inequalities, and we need to ensure those most impacted by inequalities get adequate and appropriate support. When I look to see who is in charge, and who could be in charge if the tides were to turn, and I don’t see this happening anytime soon.

[1] I’m hesitant to call them crises. As Canning (2017:9) explains in relation to the refugee ‘crisis’, a crisis is unforesessable and unavoidable. The climate crisis has been foreseen for decades, and the cost of living crisis is avoidable if you compare other European countries such as France where the impact has been mitigated by the government. The mental health crisis has also been growing for a long time and the extent to which we say today could be both foreseen and avoided.

Criminology First Week Activity (2021)

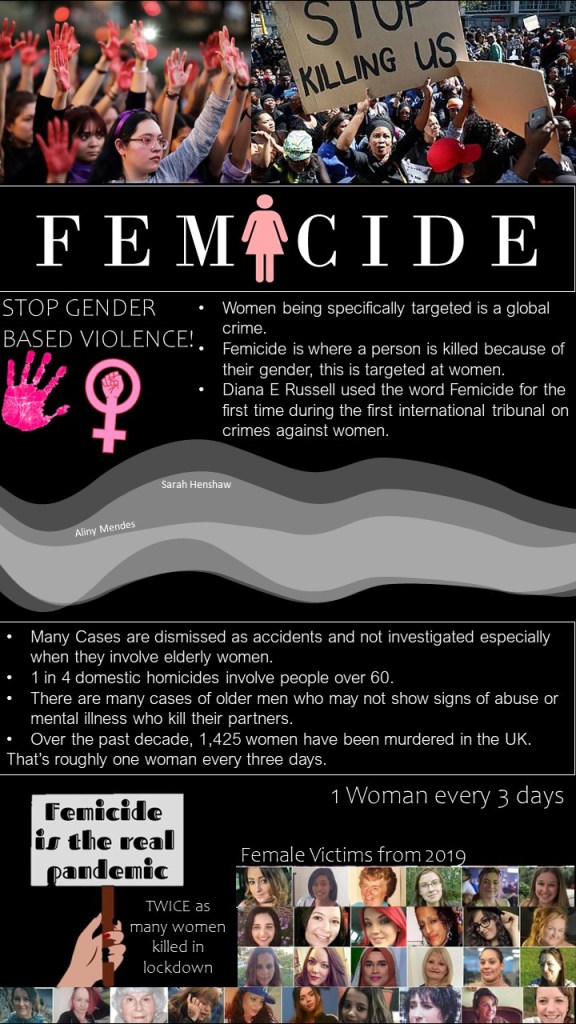

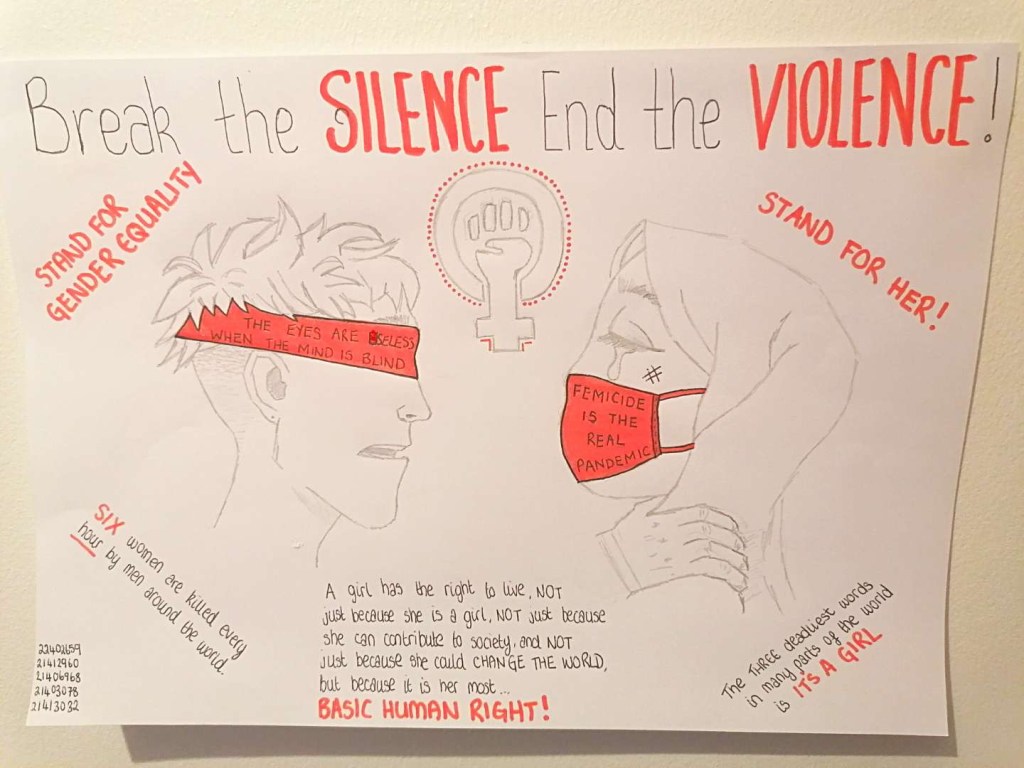

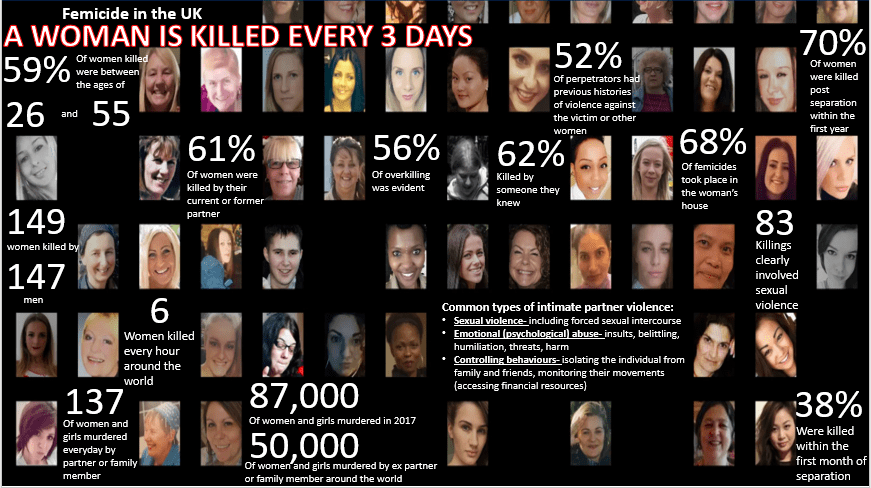

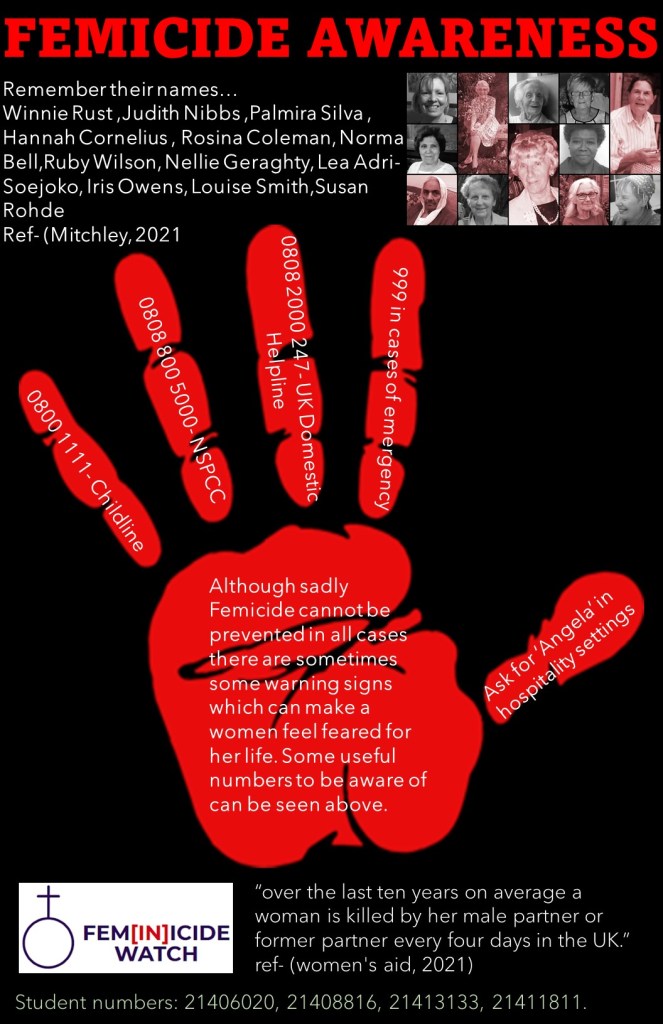

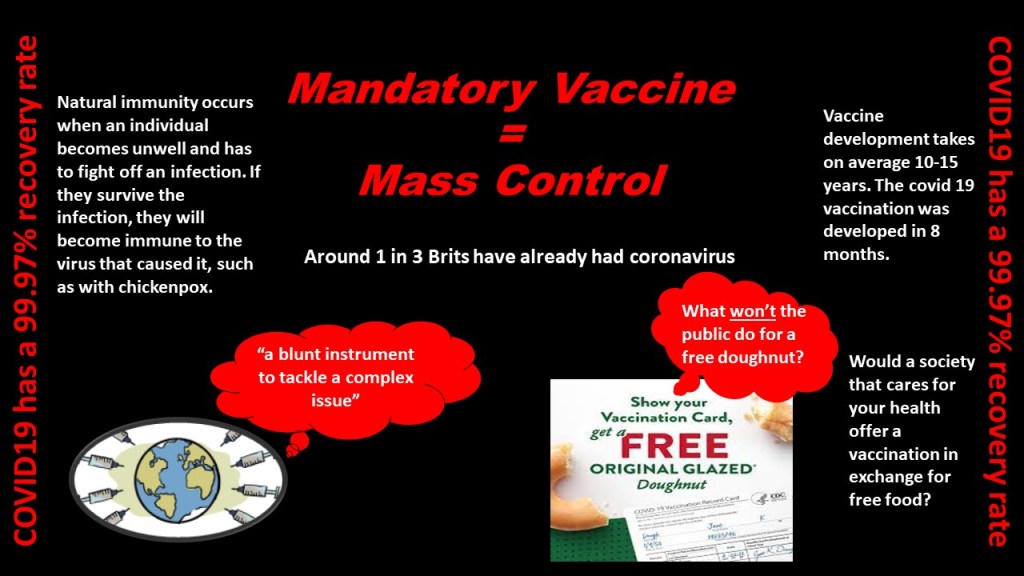

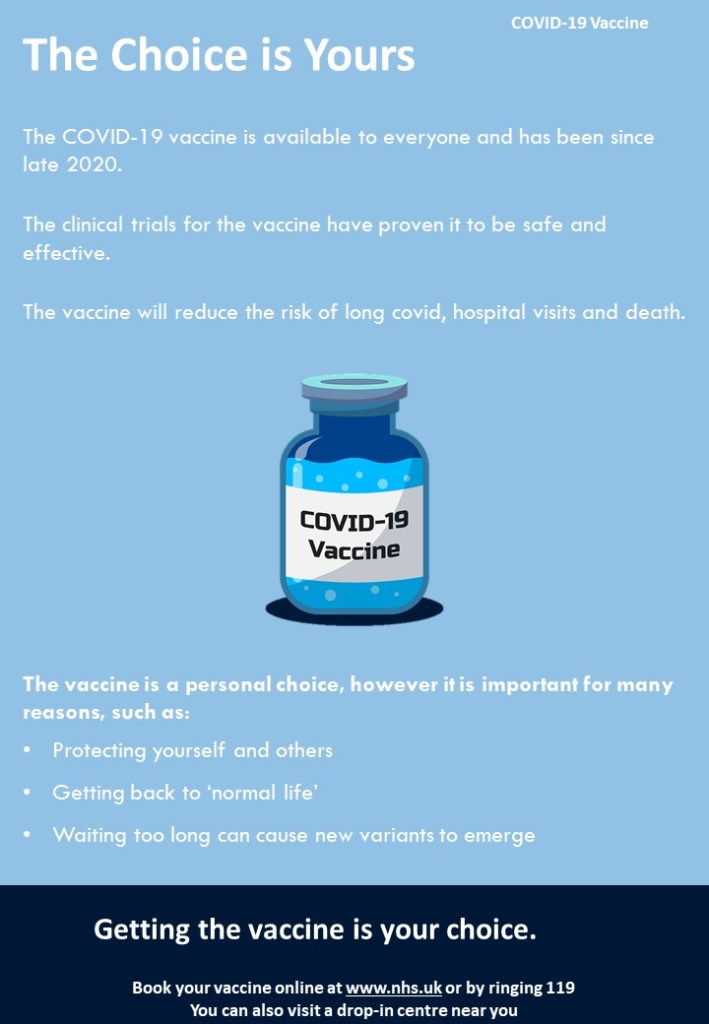

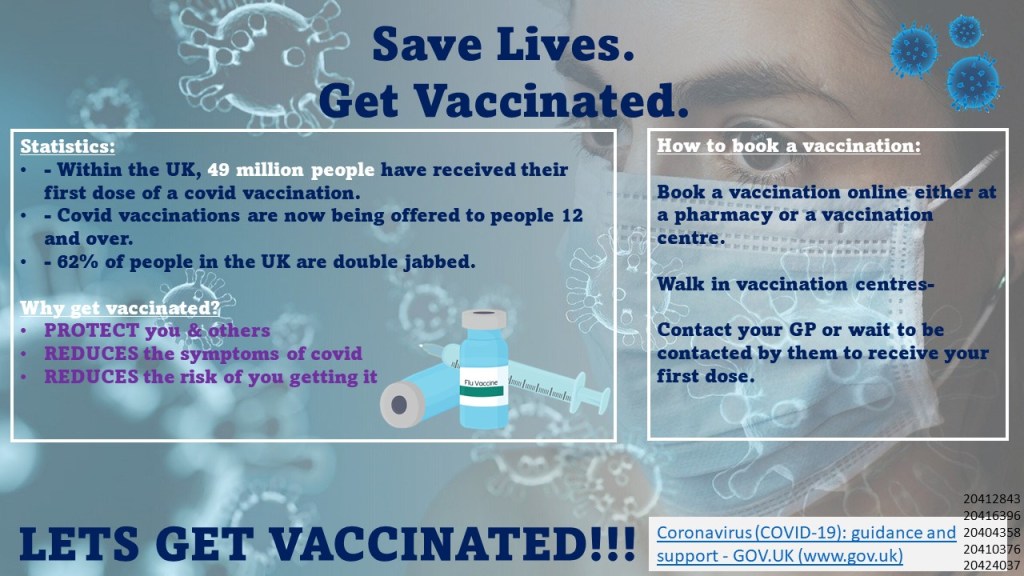

Before embarking on a new academic year, it is always worth reflecting on previous years. In 2020, the first year we ran this activity, it was a response to the challenges raised by the Covid-19 pandemic and was designed to serve two different aims. The first of these, was of course, academic, we wanted students to engage with a activity designed to explore real social problems through visual criminology, inspiring the criminological imagination for the year ahead. Second, we were operating in an environment that nobody was prepared for: online classes, limited physical contact, mask wearing, hand sanitising, socially distanced. All of these made it very difficult for staff and students to meet and to build professional relationships. The team needed to find a way for people to work together safely, within the constraints of the Covid legislation of the time and begin to build meaningful relationships with each other.

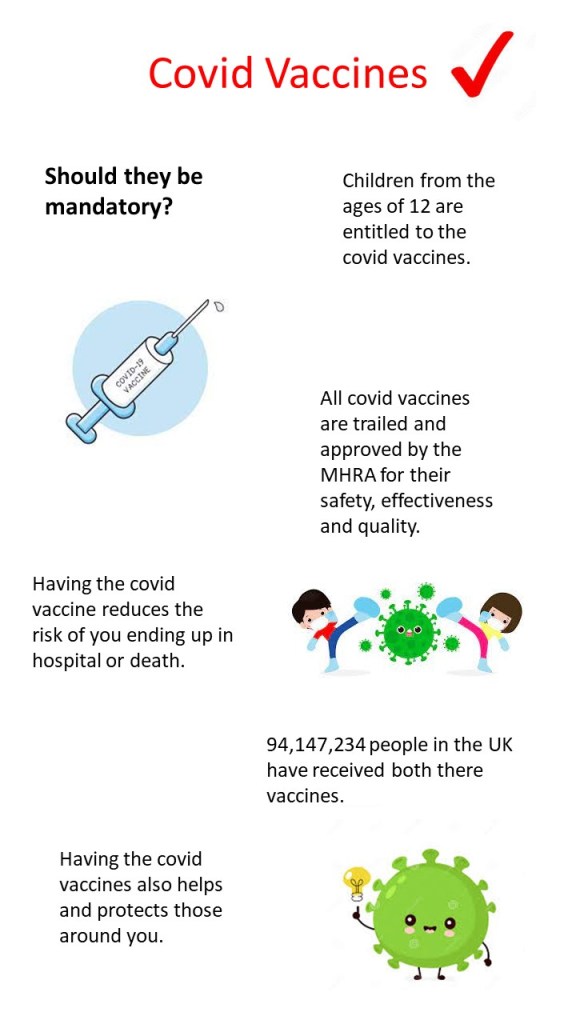

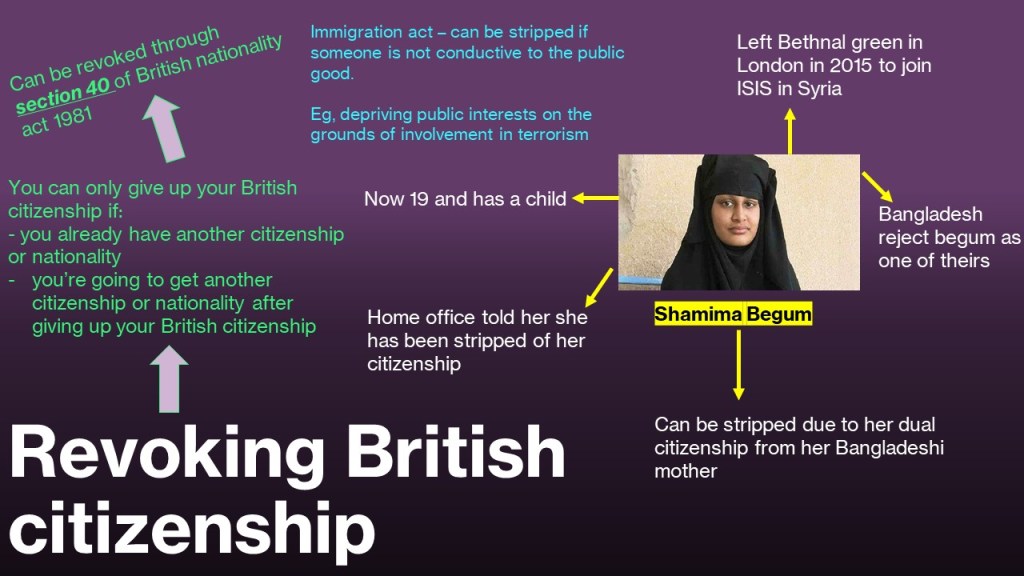

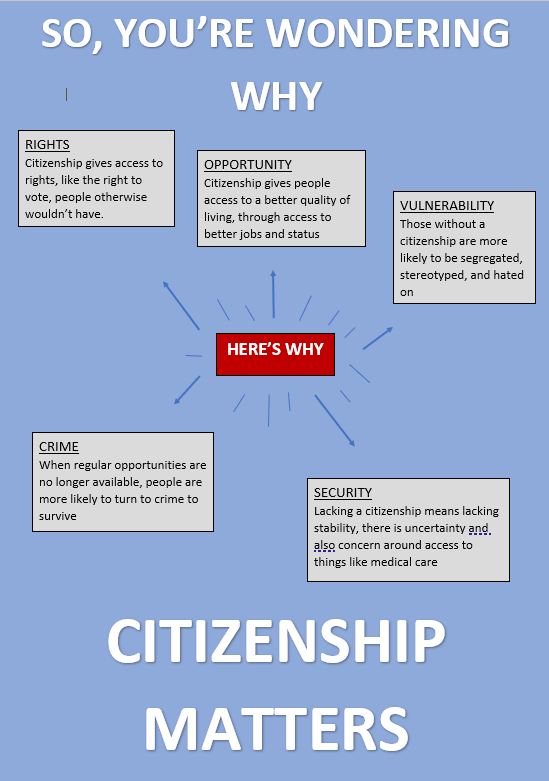

The start of the 2021/2022 academic year had its own pandemic challenges with many people still shielding, others awaiting covid vaccinations and the sheer uncertainty of going out and meeting people under threat of a deadly disease. After taking on board student feedback, we decided to run a similar activity during the first week of the new term. As before, students were placed into small groups, advised to take the default approach of online meetings (unless all members were happy to meet physically), provided with a very short prompt and limited guidance as to how best to tackle the project. The prompts were as follows:

Year 1: Femicide

Year 2: Mandatory covid vaccinations

Year 3: Revoking British citizenship

Many of the students had never physically met, yet managed to come together in the midst of a pandemic, negotiate a strategy, carry out the work and produce well designed and thoughtful, criminological posters.

As can be seen from the collage below, everyone involved embraced the challenge and created some remarkable posters. Some of these have been shared previously across social media but this is the first time they have all appeared together in one place.

I am sure everyone will agree our students demonstrated knowledge, understanding, resilience and stamina. We will be running a similar activity for the first week of the academic year 2022-2022, with different prompts to provoke thought and encourage dialogue and team work. We’ll also take on board student and staff feedback from the previous two activities. Plato once wrote that ‘our need will be the real creator’, put more colloquially, necessity is the mother of all invention, and that is certainly true of our first week activity.

Who knows what exciting ideas and posters will be demonstrated this time, but one thing is for sure Criminology students have the opportunity to flex their activism, prepare to campaign for social justice, in the process becoming real #Changemakers.