Home » Sexual offending

Category Archives: Sexual offending

25 years is but a drop in time!

If I was a Roman, I would be sitting in my comfortable triclinium eating sweet grapes and dictating my thoughts to a scribe. It was the Roman custom of celebrating a double-faced god that started European celebrations for a new year. It was meant to be a time of reflection, contemplation and future resolutions. It is under these sentiments that I shall be looking back over the year to make my final calculations. Luckily, I am not Roman, but I am mindful that over 2025 years have passed and many people, have tried to look back. Since I am not any of these people, I am going to look into the future instead.

In 25 years from now we shall be heading to the middle of the 21st century. A century that comes with great challenges. Since the start of the century there has been talk of economic bust. The banking crisis slowed down the economy and decreased real income for people. Then the expectation was that crime will rise as it did before; whilst the juries may still be out. the consensus is that this crime spree did not come…at least not as expected. People became angry and their anger was translated in changes on the political map, as many countries moved to the right.

Prediction 1: This political shift to the right in the next 25 years will intensify and increase the polarisation. As politics thrives in opposition, a new left will emerge to challenge the populist right. Their perspective will bring another focus on previous divisions such as class. Only on this occasion class could take a different perspective. The importance of this clash will define the second half of the 21st century when people will try to recalibrate human rights across the planet. Globalisation has brought unspeakable wealth to few people. The globalisation of citizenship will challenge this wealth and make demands on future gains.

As I write these notes my laptop is trying to predict what I will say and put a couple of words ahead of me. Unfortunately, most times I do not go with its suggestions. As I humanise my device, I feel sorry for its inability to offer me the right words and sometimes I use the word as to acknowledge its help but afterwards I delete it. My relationship with technology is arguably limited but I do wonder what will happen in 25 years from now. We have been talking about using AI for medical research, vaccines, space industry and even the environment. However currently the biggest concern is not AI research, but AI generated indecent images!

Prediction 2: Ai is becoming a platform that we hope will expand human knowledge at levels that we could have not previously anticipated. One of its limitations comes from us. Our biology cannot receive the volume of information created and there is no current interface that can sustain it. This ultimately will lead to a divide between people. Those who will be in favour of incorporating more technology into their lives and those who will ultimately reject it. The polarisation of politics could contribute to this divide as well. As AI will become more personal and intrusive the more the calls will be made to regulate. Under the current framework to fully regulate it seems rather impossible so it will lead to an outright rejection or a complete embrace. We have seen similar divides in the past during modernity; so, this is not a novel divide. What will make it more challenging now is the control it can hold into everyday life. It is difficult to predict what will be the long-term effects of this.

During the late 20th and early 21st centuries drug abuse and trafficking seemed to continue to scandalise the public and maintain attention as much as it did back in the 1970s and 80s. Drugs have been demonised and became the topic of media representation of countless moral panics. Its reach in the public is wide and its emotional effect rivals only that of child abuse. Is drugs abuse an issue we shall be considering in 25 years from now?

Prediction 3: People used substances as far back as we can record history. Therefore, there will be drugs in the future to the joy of all these people who like to get high! It is most likely that the focus will be on synthetic drugs that will be more focused on their effects and how they impact people. The production is likely to change with printers being able to develop new substances on a massive scale. These will create a new supply line among those who own technology to develop new synthetic forms and those who own the networks of supply. In previous times a takeover did happen so it is likely to happen again, unless these new drugs emerge under formal monopolies, like drug companies who will legalise their recreative use.

One of the biggest tensions in recent years is the possibility of another war. Several European politicians have already raised it pretending to be making predictions. Their statements however are clear signs of war preparation. The language is reminiscent of previous eras and the way society is responding to these seems that there is some fertile ground. Nationalism is the shelter of every failed politician who promises the world and delivers nothing. Whether a citizen in Europe (EU/UK) the US or elsewhere, they have likely to have been subjected to promises of gaining things, better days coming, making things great…. only to discover all these were empty vacant words. Nothing has been offered and, in most cases, working people have found that their real incomes have shrunk. This is when a charlatan will use nationalism to push people into hating other people as the solution to their problems.

Prediction 4: Unfortunately, wars seem to happen regularly in human history despite their destructive nature. We also forget that war has never stopped and elusive peace happens only in parts of the world when different interests converge. There is a combination of patriotism, national pride and rhetoric that makes people overlook how damaging war is. It is awfully blindsided not to recognise the harm war can do to them and to their own families. War is awful and destroys working people the most. In the 20th century nuclear armament led to peace hanging by a thread. This fear stupidly is being played down by fraudsters pretending to be politicians. Currently the talk about hybrid war or proxy war are used to sanitise current conflicts. The use of drones seems to have altered the methodology of war, and the big question for the next 25 years is, will there be someone who will press THAT button? I am not sure if that will be necessary because irrespective of the method, war leaves deep wounds behind.

In recent years the discussion about the weather have brought a more prevailing question. What about the environment? There is a recognised crisis that globally we seem unable to tackle, and many make already quite bleak predictions about it. Decades ago, Habermas was exploring the idea of “colonization of the lifeworld” purporting that systemic industrial agriculture will lead to environmental degradation. Now it seems that this form of farming, the greenhouse gasses and deforestation are becoming the contributing factors of global warming. The inaction or the lack of international coordination has led calls for immediate action. Groups that have been formed to pressure political indecision have been met with resistance and suspicion, but ultimately the problem remains.

Prediction 5: The world acts when confronted with something eminent. In the future some catastrophic events are likely to shape views and change attitudes. Unfortunately, the planet runs on celestial and not human time. When a prospective major event happens, no one can predict its extent or its impact. The approach by some super-rich to travel to another planet or develop something in space is merely laughable but it is also a clear demonstration why wealth cannot be in the hands of few oligarchs. Life existed before them and hopefully it will continue well beyond them. On the environment I am hopeful that people’s views will change so by the end of this century we will look at the practices of people like me and despair.

These are mere predictions of someone who sits in a chair having read the news of the day. They carry no weight and hold no substantive strength. There is a recognition that things will change at some level and we shall be asked to adapt to whatever new conditions we are faced with. In 25 years from now we will still be asking similar questions people asked 100 years ago. Whatever happens, however it happens, life always finds a way to continue.

Sabrina Carpenter and Feminist Utopia

I have recently been introduced to Sabrina Carpenter via online media commentary about the image of her new album cover Man’s Best Friend. Whilst some claim the image is playing with satire, the image appears to have been interpreted by others as being hyper-sexual and pandering to the male gaze.

I am not sure why this specific album cover and artist has attracted so much attention given that the hyper-sexual depiction of women is well-represented within the music industry and society more generally. However, because Sabrina’s main audience base is apparently young women under 30 it did leave me thinking about the module CRI1009 and feminist utopia, as it left me with questions that I would want to ask the students like: In a feminist utopia should the hyper-sexualized imagery of women exist?

Some might be quick to point out that this imagery should not exist as it could be seen to contribute towards the misogynistic sexualisation of women and the danger of this, as illustrated with Glasgow Women’s Aid comments about Sabrina’s album cover via Instagram (2025)

‘Sabrina Carpenter’s new album cover isn’t edgy, it’s regressive.

Picturing herself on all fours, with a man pulling her hair and calling it “Man’s Best Friend” isn’t subversion. 😐

It’s a throwback to tired tropes that reduce women to pets, props, and possessions and promote an element of violence and control. 🚩

We’ve fought too hard for this. ✊🏻

We get Sabrina’s brand is packaged up retro glam but we really don’t need to go back to the tired stereotypes of women. ✨

Sabrina is pandering to the male gaze and promoting misogynistic stereotypes, which is ironic given the majority of her fans are young women!

Come on Sabrina! You can do better! 💖’

However, thinking about utopia is always complicated as Sabrina’s brand appears to some a ‘sex-positive feminism’ by apparently allowing women to be free to represent themselves and ‘feel sexy’ rather than being controlled by the rules and expectations of other people. For some this idea of sexual freedom aka ‘sex-positive feminism’ branded via an inequitable capitalistic male dominated industry and represented by an incredibly rich white woman would be a bit of a mythical representation. As while this idea of sexy feminism is promoted by the privileged few this occurs in a societal context where many feel that women’s rights are being/at risk of being eroded and women are being subjected to sexual violence on a daily basis.

I am not sure what a workshop discussion with CRI1009 students would conclude about this, but certainly there would need to be a circling back to more never- ending foundational questions about utopia: what else would exist in this feminist utopia? Whose feminist utopic vision should get priority? Would anyone be damaged in a utopic society that does promote this hyper-sexualization? If so, should this utopia prioritise individual expression or have collective responsibility? In a society without hyper-sexualisation of women would there be rule breakers, and if so, what do you do with them?

Changing the Narrative around Violence Against Women and Girls

For Criminology at UON’s 25th Birthday, in partnership with the Northampton Fire, Police and Crime Commissioner, the event “Changing the Narrative: Violence Against Women and Girls” convened on the 2nd April. Bringing together a professional panel, individuals with lived experience and practitioners from charity and other sectors, to create a dialogue and champion new ways of thinking. The first in a series, this event focused on language.

All of the discussions, notes and presentations were incredibly insightful, and I hope this thematic collation does it all justice.

“A convenient but not useful term.”

Firstly an overwhelming reflection on the term itself; ‘Violence Against Women and Girls’ – does it do justice to all of the behaviour under it’s umbrella? We considered this as reductionist, dehumanising, and often only prompts thinking and action to physical acts of violence, but perhaps neglects many other harms such as emotional abuse, coercion and financial abuse which may not be seen as, or felt as ‘severe enough’ to report. It may also predominantly suggest intimate partner or domestic abuse which may too exclude other harms towards women and girls such as (grand)parent/child abuse or that which happens outside of the home. All of which are too often undetected or minimised, potentially due to this use of language. Another poignant reflection is that we may not currently be able to consider ‘women and girls’ as one group, given that girls under 16 may not be able to seek help for domestic abuse, in the same way that women may be able to. We also must consider the impact of this term on those whose gender identity is not what they were assigned at birth, or those that identify outside of the gender binary. Where do they fit into this?

To change the narrative, we must first identify what we are talking about. Explicitly. Changing the narrative starts here.

“I do not think I have survived.”

We considered the importance of lived experience in our narratives and reflected on the way we use it, and what that means for individuals, and our response.

Firstly, the terms ‘victim’ and ‘survivor’ – which we may use without thought, use as fact, particularly as descriptors within our professions, but actually these are incredibly personal labels that only individuals with such experience can give to themselves. This may be reflective of where they are in their journey surrounding their experiences and have a huge impact on their experience of being supported. It was courageously expressed that we also must recognise that individuals may not identify with either of those terms, and that much more of that person still exists outside of that experience or label. We also took a moment to remember that some victims, will never be survivors.

Lived experience is making its way into our narratives more and more, but there is still much room for improvement. We champion that if we are to create a more supportive, inclusive, practical and effective narrative, we must reflect the language of individuals with lived experience and we must use it to create a narrative free from tick boxes, from the lens of organisational goals and societal pressure.

Lived experience must be valued for what it is, not in spite of what it is.

“In some cases, we allow content – which would otherwise go against our standards – if its newsworthy.”

A further theme was a reflection on language which appears to be causing an erosion of moral boundaries. For example, the term ‘misogyny’ – was considered to be used flippantly, as an excuse, and as a scapegoat for behaviour which is not just ‘misogynistic’ but unacceptable, abhorrent, inexcusable behaviour – meaning the extent of the harms caused by this behaviour are swept away under a ‘normalised’ state of prejudice.

This is one of many terms that along with things like ‘trauma bond’ and ‘narcissist’ which have become popular on social media without any rigour as to the correct use of the term – further normalises harmful behaviour, and prevents women and girls from seeking support for these very not normal experiences. In the same vein it was expressed that sexual violence is often seen as part of ‘the university experience.’

This use of language and its presence on social media endangers and miseducates, particularly young people, especially with new posting policies around the freedom of expression. Firstly, in that many restrictions can be bypassed by the use of different text, characters and emoji so that posts are not flagged for certain words or language. Additionally, guidelines from Meta were shared and highlighted as problematic as certain content which would, and should, normally be restricted – can be shared – as long as is deemed ‘newsworthy.’

Within the media as a whole, we pressed the importance of using language which accurately describes the actions and experience that has happened, showing the impact on the individual and showing the extent of the societal problem we face… not just what makes the best headline.

“We took action overnight for the pandemic.”

Language within our response to these crimes was reflected upon, in particular around the term ‘non-emergency’ which rape, as a crime, has become catalogued as. We considered the profound impact of this language for those experiencing/have experienced this crime and the effect it has on the resources made available to respond to it.

Simultaneously, in other arenas, violence toward women and girls is considered to be a crisis… an emergency. This not only does not align with the views of law enforcement but suggests that this is a new, emerging crisis, when in fact it is long standing societal problem, and has faced significant barriers in getting a sufficient response. As reflected by one attendee – “we took action overnight for the pandemic.”

“I’ve worked with women who didn’t report rape because they were aroused – they thought they must have wanted it.”

Education was another widely considered theme, with most talk tables initially considering the need for early education and coming to the conclusion that everyone needs more education; young and old – everything in between; male, female and everything in between and outside of the gender binary. No-one is exempt.

We need all people to have the education and language to pass on to their children, friends, colleagues, to make educated choices. If we as adults don’t have the education to pass on to children, how will they get it? The phrase ‘sex education’ was reflected upon, within the context of schools, and was suggested to require change due to how it triggers an uproar from parents, often believing their children will only be taught about intercourse and that they’re too young to know. It was expressed that age appropriate education, giving children the language to identify harms, know their own body, speak up and speak out is only beneficial and this must happen to help break the cycle of generational violence. We cannot protect young people if we teach them ignorance.

Education for all was pressed particularly around education of our bodies, and our bodily experiences. In particular of female bodies, which have for so long been seen as an extension of male bodies. No-one knows enough about female bodies. This perpetuates issues around consent, uneducated choices and creates misplaced and unnecessary guilt, shame and confusion for females when subjected to these harms.

“Just because you are not part of the problem, does not mean you are part of the solution.“

Finally, though we have no intention or illusion of resolution with just one talk, or even a series of them – we moved to consider some ways forward. A very clear message was that this requires action – and this action should not fall on women and girls to protect themselves, but for perpetrators for be stopped. We need allies, of all backgrounds, but in particular, we need male allies. We need male allies who have the education, and the words necessary to identify and call out the behaviour of their peers, their friends, their colleagues, of strangers on the bus. We asked – would being challenged by a ‘peer’ have more impact? Simply not being a perpetrator, is not enough.

Everyone loves a man in uniform: The Rise and Fall of Nick Adderley

Some of our local readers will be familiar with the case of former Chief Constable Nick Adderley who was recently dismissed from Northamptonshire Police. The full Regulation 43 report can be found here and it provides an interesting, and at times, comical, narrative of the life and times of the now disgraced police officer.

The Regulation 43 report describes Adderley’s creation of a “false legend” of military service, whereby this supposed naval man fought bravely to protect the Falkland Islands (despite only being 15 when the conflict ended), rescued helicopters and ships in the height of battle, commanded men, was a military negotiator during the Anti-Duvalier protest movement in Haiti. In short, an all round real-life Naval action man! It’s pity for Adderley, that the Regulation 43 panel found none of this was true, instead a ‘Walter Mitty‘ like trail of lies were revealed throughout the investigation.

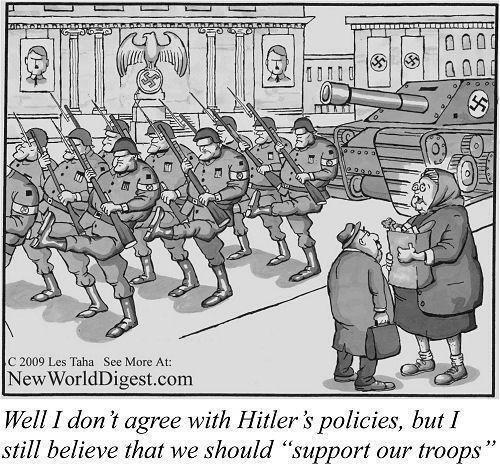

Nevertheless, not content with his brave military career, our intrepid hero decided he would take his considerable (in his estimation at least) skills into policing. First applying to Greater Manchester Police [GMP] (who turned him down on the grounds that there were ‘better candidates’) and then Cheshire Police. From Cheshire Police, he went to GMP and then to Staffordshire Police, finally arriving in Northamptonshire in the summer of 2018. Despite all of these different forces, all of the different application and promotion forms that our brave hero completed, not one person bothered to check that he was telling the truth. To check that this man, responsible for upholding law and order, was a fit candidate for the role. instead, I suspect, like so many it seems, we are so in love with our military and all its trappings, that we lose any sense of criticality when it comes to uniforms. After all who would dare to question a Chief Constable, whether a police officer, civilian worker or member of the public? Easier to keep parroting the mantra of “our brave boys”, than to think critically about institutions and their members, as the cartoon below demonstrates all too well.

At this point Adderley has been dismissed from Northamptonshire Police and banned from policing. In 2024 the Angiolini Inquiry published its report, which in part focused on police vetting and there is no doubt, post-Adderley the police as an institution, will undertake more soul searching. Additionally, some commentators have begun a campaign to have Adderley’s police pension reduced/removed. These matters will continue to rumble along for some time. But, in short, Adderley has been punished and publicly outed as a liar, but that does not begin to undo the immense harm his behaviour has inflicted on the community.

During his time at Chief Constable of Northamptonshire, Adderley called upon his supposed military history and experience to support his arguments and the decisions he made. For instance, the 2019 arming of Northamptonshire’s police with tasers or the 2020 launch of eight interceptors, described by Adderley as “a new fleet of crime-busting cars” or the 2021 purchase of “eight Yamaha WR450F enduro bikes“. To me, all of these developments scream the militarisation of policing. Since the very foundation of the Metropolitan Police in 1829, serving officers and the public have continually been opposed to arming the police, yet Adderley, with his military service, seemingly knew best. But what use is a taser, fast car or motorbike in everyday community policing, how do they help when responding to domestic abuse, sexual violence, or the very many mental health crises to which officers are regularly called? How do these expensive military “toys” ensure that all members of society feel protected and not just some communities? How can we ensure that tasers don’t do lasting harm to those subjected to their violence? Instead all of these developments scream a fantasy of both military and policing, one in which the hero is always on the side of the righteous, devoting his life to taking down the “baddies” by whatever means necessary.

Ultimately for the people of Northamptonshire we have to decide, can we view Adderley’s police leadership as the best use of taxpayers’ money, a response to evidence based policing or just a military fantasy of the man who lied? More importantly, the county and its police force will struggle to untangle Adderley’s web of lies and the harm inflicted on the people of Northamptonshire, making it likely that this entirely unevidenced push to militarise the police will continue unchecked.

Justice or Just Another One?

Luckily I’ve never been one for romantic movies. I always preferred a horror movie. I just didn’t know that my love life would become the worst horror movie I could ever encounter. I was only 18 when I met the monster who presented as a half decent human being. I didn’t know the world very well at that point and he made sure that he became my world. The control and coercion, at the time, seemed like romantic gestures. It’s only with hind sight that I can look back and realise every “kind” and “loving” gesture came from a menacing place of control and selfishness. I was fully under his spell. But anyway, I won’t get into every detail ever. I guess I just wanted to preface this with the fact that abuse doesn’t just start with abuse. It starts with manipulation that is often disguised as love and romance in a twisted way.

This man went on to break me down into a shell of myself before the physical abuse started. Even then, him getting that angry was somehow always my fault. I caused that reaction in his sick, twisted mind and I started to believe it was my fault too. The final incident took place and the last thing I can clearly recall is hearing how he was going to cave my head in before I felt this horrendous pressure on my neck with his other hand keeping me from making any noise that would expose him.

By chance, I managed to get free and RUN to my family. Immediately took photos of my injuries too because even in my state, I know how the Criminal Justice System would not be on my side without evidence they deemed suitable.

Anyway, my case ended up going to trial. Further trauma. Great. I had to relive the entire relationship by having every part of my character questioned on the stand like I was the criminal in this instance. I even got told by his defence that I had “Histrionic Personality Disorder”. Something I have never been diagnosed with, or even been assessed for. Just another way the CJS likes to pathologise women’s trauma. Worst of all, turns out ‘Doctor Defence’ ended up dropping my abuser as he was professionally embarrassed when he realised he knew my mother who was also a witness. Wonderful. This meant I got to go through the process of being criminalised, questioned, diagnosed with disorders I hadn’t heard of at the time, hear the messages, see the photos ALL over again.

Although “justice” prevailed in as much as he was found guilty. All for the sake of a suspended sentence. Perfect. The man who made me feel like he was my world then also tried to end my life was still going to be free enough to see me. The law wasn’t enough to stop him from harming me, why would it be enough to stop him now?

Fortunately for me, it stopped him harming me. However, it did not stop him harming his next victim. For the sake of her, I won’t share any details of her story as it is not mine to share. Yet, this man is now behind bars for a pretty short period of time as he has once again harmed a woman. Evidently, I was right. The law was not enough to stop him. Which leads me to the point of this post, at what stage does the CJS actually start to take women’s pleas to feel safe seriously? Does this man have to go as far to take away a woman’s life entirely before someone finally deems him as dangerous? Why was my harm not enough? Would the CJS have suddenly seen me as a victim, rather than making me feel like a criminal in court, if I was eternally silenced? Why do women have to keep dying at the hands of men because the CJS protects domestic abusers?”

Media Madness

Unless you have been living under a rock or on a remote island with no media access, you would have been made aware of the controversy of Russell Brand and his alleged ‘historic’ problematic behaviour. If we think about Russell Brand in the early 2000s he displayed provocative and eccentric behaviour, which contributed to his rise to fame as a comedian, actor, and television presenter. During this period, he gained popularity for his unique style, which combined sharp wit, a proclivity for wordplay, and a rebellious, countercultural persona.

Brand’s stand-up comedy routines was very much intertwined with his personality, which was littered with controversy, something that was welcomed by the general public and bosses at big media corporations. Hence his never-ending media opportunities, book deals and sell out shows.

In recent years Brand has reinvented (or evolved) himself and his public image which has seen a move towards introspectivity, spirituality and sobriety. Brand has collected millions of followers that praise him for his activist work, he has been vocal on mental health issues, and he encourages his followers to hold government and big corporations to an account.

The media’s cancellation of Russell Brand without any criminal charges being brought against him raises important questions about the boundaries of cancel culture and the presumption of innocence. Brand, a controversial and outspoken comedian, has faced severe backlash for his provocative statements and unconventional views on various topics. While his comments have undoubtedly sparked controversy and debate, the absence of any criminal charges against him highlights the growing trend of public figures being held to account in the court of public opinion, often without a legal basis.

This situation underscores the importance of distinguishing between free speech and harmful behaviour. Cancel culture can sometimes blur these lines, leading to consequences that may seem disproportionate to the alleged transgressions. The case of Russell Brand serves as a reminder of the need for nuanced discussions around cancel culture, ensuring that individuals are held accountable for their actions while also upholding the principle of innocent until proven guilty in a court of law. It raises questions about how society should navigate the complex intersection of free expression, public accountability, and the potential consequences for individuals in the public eye.

There is also an important topic that seems to be forgotten in this web of madness……..what about the alleged victims. There seems to be a theme that continuously needs to be highlighted when criminality and victimisation is presented. There is little discussion or coverage on the alleged victims. The lack of media sensitivity and lay discussion on this topic either dehumanises the alleged victims by using lines such as ‘Brand is another victim of MeToo’ and comparing him to Cliff Richard and Kevin Spacey, two celebrities that were accused of sexual crimes and were later found not guilty, which in essence creates a narrative that does not challenge Brand’s conduct, on the basis of previous cases that have no connection to one another.

We also need to be mindful on the medias framing of the alleged witch hunt against Russell Brand and the problematic involvement that the UK government. The letter penned by Dame Dinenage sent to social media platforms in an attempt to demonetize Brand’s content should also be highlighted. While I support Brand being held accountable for any proven crimes he has committed, I feel these actions by UK government are hasty, and problematic considering there have been many opportunities for the government to step in on serious allegations about media personalities on the BBC and other news stations and they have not chosen to act. The step made by Dame Dinenage has contributed to the media madness and contributes to the out of hand and in many ways, nasty discussion around freedom of speech. The government’s involvement has deflected the importance of the victimisation and criminality. Instead, it has replaced the discussion around the governments overarching punitive control over society.

Brand has become a beacon of understanding to is 6.6 million followers during Covid 19 lockdowns, mask mandates and vaccinations. This was at a time when many people questioned government intentions and challenged the mainstream narratives around autonomy. Because Brand has been propped up as a hero to his ‘awakened’ followers the shift around his conduct and alleged crimes have been erased from conversation and debates around BIG BROTHER and CONTROL continue to shape the media narrative………

What cost justice? What crisis?

The case of Andrew Malkinson represents yet another in the long list of miscarriages of justice in the United Kingdom. Those that study criminology and those practitioners involved in the criminal justice system have a reasonable grasp of how such cases come about. More often than not it is a result of police malpractice, negligence, culture and error. Occasionally it is as a result of poor direction in court by the trial judge or failures by the CPS, the prosecution team or even the defence team. The tragic case of Stefan Kiszko is a good example of multiple failures by different bodies including the defence. Previous attempts at addressing the issues have seen the introduction of new laws such as the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 and the Criminal Procedure and Investigations Act 1996. The former dealing in part with the treatment of suspects in custody and the latter with the disclosure of documents in criminal proceedings. Undoubtedly there have been significant improvements in the way suspects are dealt with and the way that cases are handled. Other interventions have been the introduction of the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS), removing in part, charging decisions from the police and the introduction of the Criminal Cases Review Commission (CCRC) to review cases where an appeal has been lost but fresh evidence or information has come to light.

And yet, despite better police training regarding interviews and the treatment of suspects, better training in investigations as a whole, new restrictive laws and procedures, the independence of the CPS, the court appeal system and oversight by a body such as the CCRC, miscarriages of justice still occur. What sets the Malkinson case aside from the others appears to be the failure of the CCRC to take action on new information. The suggestion being that the decision was a financial one, with little to do with justice. If the latter is proved to be true, we will of course have to wait for the results of the inquiry, then how can anyone have any confidence in the justice system?

Over the years we have already seen swingeing cuts in budgets in the criminal justice system such that the system is overloaded. Try to pop into the local police station to make a complaint of a crime, you won’t find a station open to the public. Should you have been unfortunate enough to have been caught for some minor misdemeanour and need to go to magistrates’ court for a hearing, you’ll be lucky if you don’t have to travel some considerable distance to get there, good luck with that if you rely on public transport. Should you be the victim of a more serious crime or indeed charged with a more serious offence, triable in crown court, then you’ll probably wait a couple of years before the trial. Unfortunate if you are the alleged offender and on remand, and if you are the victim, you could be forgiven for deciding that you’d rather put it all behind you and disengage with the system. But even to get to that stage, there has to be sufficient evidence to secure a prosecution and it has to be in the public interest to do so. Your day in court as a victim is likely to be hang on the vagaries of the CPS decision making process. A process that has one eye on the court backlog and another on performance targets. Little wonder the attrition rate in sex offences is so high. Gone are the days of letting a jury decide on occasions where the evidence hangs on little more than one person’s word against the other.

Andrew Malkinson and his legal representative have called for a judicial review, a review where witnesses can be compelled to attend to give evidence and documentary evidence can be demanded to be produced. Instead, the government has said there will be an independent inquiry. On a personal note, I have little faith in such inquiries. My experience is that they are rarely independent of government direction and wishes. Andrew Malkinson’s case is a travesty and the least that can be done is to have a proper inquiry. I suspect though that the Malkinson case might just be the tip of the iceberg. The Criminal Justice System is in crisis but budgetary restraint and political whim seem to be far more important than justice. We can look forward to more finger pointing and yet more reorganisation and regulation.

A world without prisons follow-up. A student/staff reflection piece

As a department Criminology has pushed the envelope in promoting discussions around the key disciplinary debates. @franbitalo and myself co-ordinated a conversation where the main focus was to imagine “a world without prisons”. The conversation was very interesting, and we decided to post parts of it as a legacy of the social debates we engage in. The discussion is captured as a series of comments made by the students with some prompts in bold.

The original question stands, can you imagine a world without prisons? First thing first, there is a feeling that prisons will always exist as mechanisms to control our society. Mainly because our society is too punitive and focused on punishment rather than rehabilitation. We live in a society that ideologically sees the prison as the representation of being hard on crime. Further to this point we may never be able to abolish the prison, so it can always remain as the last resort of what to do with those who have harm others. Especially for those in our society who deserve to be punished because of what they did. Perhaps we could reform it or extend the use of the probation service dealing with crime.

In an ideal world prisons should not exist especially because the system seems to target particular groups, namely minorities and people from specific background. It important to note that it does stop people seeking or taking justice into their hands and deflecting any need for vengeance “eye for an eye”. Prison is a punishment done in the name of society, but it does carry political overtones. There are parts of political ideology that support the idea that punishment is meant to make an example of those breaking the law. This approach is deeply rooted, and is impervious to reform or change. Which can become one of the biggest issues regarding prisons.

Then there is the public’s view on prisons. When people hear that prisons will go they will be very unhappy and even frightened. They will feel that without prisons people will go crazy and commit crimes without any consequences. Society, people feel, will go into a state of anarchy where vigilantism will become the acceptable course of action. This approach becomes more urgent when considering particular types of criminals, like sex offenders and in particular, paedophiles. Regardless of the intention of the act, these types of crime cause serious harm that the victim carries for the rest of their lives. The violation of trust and the lack of consent makes these crimes particularly repulsive and prison worthy. How about child abduction? Not sure if we should make prison crime specific. That will not serve its purpose, instead it will make it the dumping ground for some crime categories, sending a message that only some people will go to prison.

Will that be the only crime category worthy of prison? In an ideal world, those who commit serious financial crimes should be going to prison, if such a prison existed. Again, here if we are considering harm as the reason to keep prisons open these types of crime cause maximum harm. The implication of white-collar crime, serious fraud and tax evasion deprive our society of taxes and income that is desperately needed in social infrastructure, services and social support. Financial crime flaunts the social contract and weakens society. Perhaps those involved should be made to contribute reparations. The prison question raises another issue to consider especially with all the things said before! Who “deserves” to go to prison. Who gets to go and who is given an alternative sentence is based on established views on crime. There are a lot of concerns on the way crime is prioritised and understood because these prioritisations do not reflect the reality of social disorder. Prison is an institution that scapegoats the working classes. Systematically the system imprisons the poor because class is an imprisonable factor; the others being gender and race.

If we keep only certain serious crimes on the books, we are looking at a massive reduction in prison numbers. Is that the way to abolitionism? The prison plays too much of a role in the Criminal Justice System to be discounted. The Industrial Prison Complex as a criminological concept indicates the strengths of an institution that despite its failings, hasn’t lost its prominence. On the side of the State, the establishment is a barrier to any reform or changes to this institution. Changes are not only needed for prison, but also for the way the system responds to the victims of crime as well. Victims are going through a process of re-victimisation and re-harming them. This is because the system is using the victims as part of the process, in giving evidence. If there is concern for those harmed by crime, that is not demonstrated by the strictness of the prison.

As a society currently we may not be able to abolish prisons but we ought to reduce the harm punishment has onto people. In order to abolish prisons, the system will have to be ready to allow for the change to happen. In the meantime, alternative justice systems have not delivered anything different from what we currently have. One of the reasons is that as a society we have the need to see justice being served. A change so drastic as this will definitely require a change in politics, a change in ideology and a change in the way we view crime as a society in order to succeed. The conversation continues…

Thank you to all the participating students: Katja, Aimee, Alice, Zoe, Laura, Amanda, Kayleigh, Chrissy, Meg, and Ellie also thank you to my “partner in crime” @franbitalo.

The Problem is Bigger than Tate

While there are many things that have got under my skin lately, it seems that every time I go on social media, turn on the television, or happen to have a conversation, the name Andrew Tate is uttered. His mere existence is like a virus, attacking not only my brain and soul but it seems a large population of the world. His popularity stems from his platform followed by thousands of men and young boys (it’s known as the ‘Real World’).

His platform ‘educating’ men on working smarter not harder has created a ‘brotherhood’ within the manosphere that celebrates success and wealth. Tate is framed as a man’s man, physically strong, rich and he even has a cigar attached to his hand (I wonder if he puts it down when he goes to the bathroom). It seems many of his aspiring followers want to mimic his fast rich lifestyle.

This seems to be welcomed, especially now when the price of bread has significantly risen (many of his followers would sell the closest women in their life for a whiff of his cigar, and of course to be deemed to have an Insta-desirable lifestyle). While this ideology has gained hype and mass traction in recent years (under the Tate trademark) it seems that his narcissistic, problematic image and what he stands for has only just been deemed a problem … due to his recent indiscretions.

There is now outrage in UK schools over the number of young boys following Tate and his misogynistic ideology. But I cannot help but ask … why was this not an issue before? I am aware of rape culture, victim blaming, sexual harassment, and systems of silence at every level of the UK education establishment. The launch of ‘Everyone’s Invited’ shone a light on the problematic discourse, so why are we only seeing that there is a problem now?

There are many reasons why there’s a delayed outrage, and I would be here all day highlighting all the problems. So, I will give you a couple of reasons. The first is the Guyland ideology: many Tate supporters who fall into the cultural assumption of masculinity expect to be rewarded for their support, in ways of power and material possession (this includes power over women and others deemed less powerful). If one does not receive what they believe they are owed or expected, they will take what they believe they are owed (by all means necessary).

There is also a system of silence within their peer group which is reinforced by parents, female friends, the media, and those that are in administrative power. The protection of toxic behavior has been continuously put under the umbrella of ‘boys will be boys’ or the idea that the toxic behavior is outside the character of the individual or not reflective of who they truly are.

I will go one step further and apply this to the internalised patriarchy/misogyny of the many women that came out and supported Jeremy Clarkson when he callously attacked Meghan. While many of the women have their individual blight with Meghan for reasons I do not really care to explore, by supporting the rhetoric spewed by Clarkson, they are upholding systemic violence against women.

The third point is that capitalism overthrows humanity and empathy in many ways. All you need to do is to look at a history books, it seems that lessons will never be learned. The temptation of material possessions has overthrown morality. The media gives Tate a platform and in turn Tate utters damaging ideology. This brings more traffic to the platforms that he is on and thus more money and influence….after all he is one of the most googled people in the world.

The awareness of the problematic behaviour and the total disregard for protecting women and girls from monsters like Tate shows, how the outrage displayed by the media about harms against victims such as Sabina Nessa and Sarah Everard is performative. The news coverage and the discussion that centred on the victimisation of these two women have easily been forgotten. If the outrage is real then why are we still at a point where we are accepting excuses and championing misogyny under the guise of freedom of speech, without challenging the harm it really does.

It seems that society is at a point of total desensitization where there is more interest in Tate losing an argument with Greta Thunberg, posing with a cigar on an exotic beach for likes, than really acknowledging the bigger picture. Andrew Tate has been accused of rape and human trafficking. The worst thing is, this is not the first time that he has been accused of horrific crimes – and with the audio evidence that was released to the press recently, he should be in prison. But with the issues that permeate the Met police there is no surprise as to why he has been given the green light to continue his violent behaviour. But this is not just a UK issue. There has been a large amount of support overseas with young men and boys marching in masses in support of Tate, so I cannot be surprised that he was able to and continues to build a platform that celebrates and promotes horrendous treatment of women.

For many the progression of a fair and equal society is an aspiration, but for the supporters of the Tate’s in the world they tend to lean on the notion that they are entitled to more, and to acquire what they think they are owed, and will behave to the extreme of toxicity. While it is easy to fixate on a pantomimic villain like Tate to discuss his problematic use of language and how this translates in schools, the bigger picture of institutionalised patriarchy is always being missed.

It is important to unpick the toxic nature of our society, to understand the contributing factors that have allowed Andrew Tate and others like him to be such influential figures.