Home » Racism (Page 5)

Category Archives: Racism

The Chauvin verdict may not be the victory we think it is

At times like this I often hate to be the person to take what little hope people may have had away from them, however, I do not believe the Chauvin verdict is the victory many people think it is. I say people, but I really mean White people, who since the Murder of George Floyd are quite new to this. Seeing the outcry on social media from many of my White colleagues that want to be useful and be supportive, sometimes the best thing to do in times like these is to give us time to process. Black communities across the world are still collectively mourning. Now is the time, I would tell these institutions and people to give Black educators, employees and practitioners their time, in our collective grief and mourning. After the Murder of George Floyd last year, many of us Black educators and practitioners took that oppurtunity to start conversations about (anti)racism and even Whiteness. However, for those of us that do not want to be involved because of the trauma, Black people recieving messages from their White friends on this, even well-meaning messages, dredges up that trauma. That though Derek Chauvin recieved a guilty verdict, this is not about individuals and he is still to recieve his sentence, albeit being the first White police officer in the city of Minneapolis to be convicted of killing a Black person.

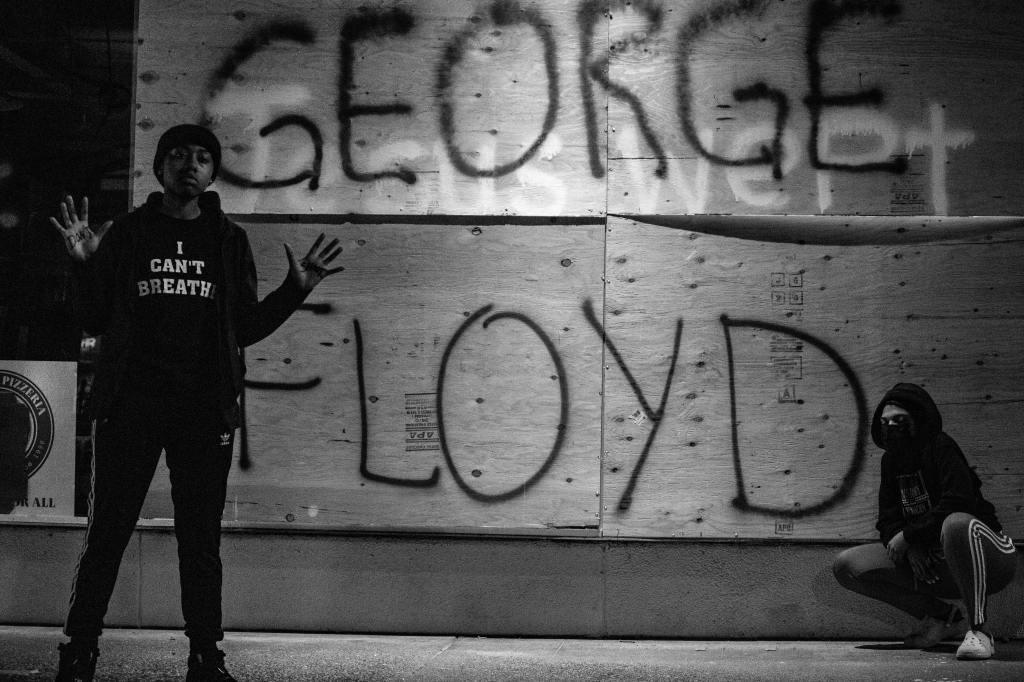

Under the rallying cry “I can’t breathe” following the 2020 Murder of George Floyd, many of us went to march in unison with our American colleagues. Northamptonshire Rights and Equality Council [NREC] organised a successful protest last summer where nearly a thousand people turned up. And similar demonstrations took place across the world, going on to be the largest anti-racist demonstration in history. However, nearly a year later, institutional commitments to anti-racism have withered in the wind, showing us how performative institutions are when it comes to pledges to social justice issues, very much so in the context race. I worry that the outcome of the Chauvin verdict might become a “contradiction-closing case”, reiterating a Facebook post by my NREC colleague Paul Crofts.

For me, a sentence that results in anything less than life behind bars is a failure of the United States’ criminal justice system. This might be the biggest American trial since OJ and “while landmark cases may appear to advance the cause of justice, opponents re-double their efforts and overall little or nothing changes; except … that the landmark case becomes a rhetorical weapon to be used against further claims in the future” (Gillborn, 2008). Here, critical race theorist David Gillborn is discussing “the idea of the contradiction-closing case” originally iterated by American critical race theorist Derrick Bell. When we see success enacted in landmark cases or even movements, it allows the state to show an image of a system that is fair and just, one that allows ‘business as usual’ to continue. Less than thirty minutes before the verdict, a sixteen-year-old Black girl called Makiyah Bryant was shot dead by police in Columbus, Ohio. She primarily called the police for help as she was reportedly being abused. In her murder, it pushes me to constantly revisit the violence against Black women and girls at the hands of police, as Kimberlé Crenshaw states:

“They have been killed in their living rooms, in their bedrooms, in their cars, they’ve been killed on the street, they’ve been killed in front of their parents and they’ve been killed in front of their children. They have been shot to death. They have been stomped to death. They have been suffocated to death. They have been manhandled to death. They have been tasered to death. They have been killed when they have called for help. They have been killed while they have been alone and they have been killed while they have been with others. They have been killed shopping while Black, driving while Black, having a mental disability while Black, having a domestic disturbance while Black. They have even been killed whilst being homeless while Black. They have been killed talking on the cellphone, laughing with friends, and making a U-Turn in front of the White House with an infant in the back seat of the car.”

Professor Kimberlé Crenshaw (TED, 2018)

Whilst Chauvin was found guilty, a vulnerable Black girl was murdered by the very people she called for help in a nearby state. Richard Delgado (1998) argues “contradiction-closing cases … allow business as usual to go on even more smoothly than before, because now we can point to the exceptional case and say, ‘See, our system is really fair and just. See what we just did for minorities or the poor’.” The Civil Rights Movement in its quest for Black liberation sits juxtaposed to what followed with the War on Drugs from the 1970s onwards. And whilst the Stephen Lawrence Inquiry was seemingly one of the high points of British race relations followed with the 2001 Race Relations Act, it is a constant fallback position in a Britain where racial inequalities have exasperated since. That despite Macpherson’s landmark report, nothing really has changed in British policing, where up until recently London Metropolitan Police Service had a chief that said it wasn’t helpful to label police as institutionally racist.

Scrolling the interweb after the ruling, it was telling to see the difference of opinion between my White friends and colleagues in comparison to my Black friends and colleagues. White people wrote and tweeted with more optimism, claiming to hope that this may be the beginning of something upward and forward-thinking. Black people on the other hand were more critical and did not believe for a second that this guilty verdict meant justice. Simply, this ruling meant accountability. Since the Murder of George Floyd, there have been numbers of conversations and discourses opened up on racism, but less so on White supremacy as a sociopolitical system (Mills, 2004). My White colleagues still thinking about individuals rather than systems/institutions simply shows where many of us still are, where this trial became about a “bad apple”, without any forethought to look at the system that continues enable others like him.

Even if Derek Chauvin gets life, I am struggling to be positive since it took the biggest anti-racist demonstration in the history of the human story to get a dead Black man the opportunity at police accountability. Call me cynical but forgive me for my inability to see the light in this story, where Derek Chauvin is the sacrificial lamb for White supremacy to continue unabted. Just as many claimed America was post-racial in 2008 with the inaugaration of Barack Obama into the highest office in the United States, the looming incarceration (I hope) of Derek Chauvin does not mean policing suddenly has become equal. Seeing the strew of posts on Facebook from White colleagues and friends on the trial, continues to show how White people are still centering their own emotions and really is indicative of the institutional Whitenesses in our institutions (White Spaces), where the centreing of White emotions in workspaces is still violence.

Derek Chauvin is one person amongst many that used their power to mercilessly execute a Black a person. In our critiques of institutional racism, we must go further and build our knowledge on institutional Whiteness, looking at White supremacy in all our structures as a sociopolitical system – from policing and prisons, to education and the third sector. If Derek Chauvin is “one bad apple”, why are we not looking at the poisoned tree that bore him?

Referencing

Delgado, Richard. (1998). Rodrigo’s Committee assignment: A sceptical look at judicial independence. Southern California Law Review, 72, 425-454.

Gillborn, David. (2008). Racism and education: Coincidence or conspiracy? London: Routledge.

Mills, Charles (2004) Racial Exploitation and the Wages of Whiteness. In: Yancy, George (ed). What White Looks Like: African American Philosophers on the Whiteness Question. London: Routledge.

TED (2018). The urgency of intersectionality | Kimberlé Crenshaw. YouTube [online]. Available.

White Spaces. Institutional Witnesses. White Spaces. Available.

Chauvin’s Guilty Charges #BlackAsiaWithLove

Charge 1: Killing unintentionally while committing a felony.

Charge 2: Perpetrating an imminently dangerous act with no regard for human life.

Charge 3: Negligent and culpable of creating an unreasonable risk.

Guilty on all three charges.

Today, there’s some hope to speak of. If we go by the book, all the prosecution’s witnesses were correct. Former police officer Chauvin’s actions killed George Floyd. By extension, the other two officers/overseers are guilty, too, of negligence and gross disregard for life. They taunted and threatened onlookers when they weren’t helping Chauvin kneel on Floyd. Kneeling on a person’s neck and shoulders until they die is nowhere written in any police training manual. The jury agreed, and swiftly took Chauvin into custody . Yet, contrary to the testimonials of the police trainers who testified against Chauvin’s actions, this is exactly what policing has been and continues to be for Black people in America.

They approached Floyd as guilty and acted as if they were there to deliver justice. No officer rendered aid. Although several prosecution witnesses detailed how they are all trained in such due diligence, yet witnesses and videos confirm not a bit of aid was rendered. In fact, the overseers hindered a few passing-by off-duty professionals from intervening to save Floyd’s life, despite their persistent pleas. They acted as arbiters of death, like a cult. The officers all acted in character.

Teenager Darnella Frazier wept on the witness stand as she explained how she was drowning in guilt sinceshe’d recorded the video of Chauvin murdering Mr. Floyd. She couldn’t sleep because she deeply regrated not having done more to save him, and further worried for the lives many of her relatives – Black men like George Floyd, whom she felt were just as vulnerable. When recording the video, Ms. Frazier had her nine-year-old niece with her. “The ambulance had to push him off of him,” the child recounts on the witness stand. No one can un-see this incident.

History shows that her video is the most vital piece of evidence. We know there would not have even been a trial given the official blue line (lie). There would not have been such global outcry if Corona hadn’t given the world the time to watch. Plus, the pandemic itself is a dramatic reminder that “what was over there, is over here.” Indeed, we are all interconnected.

Nine minutes and twenty seconds of praying for time.

Since her video went viral last May, we’d seen footage of 8 minutes and 46 seconds of Chauvin shoving himself on top of ‘the suspect’. Now: During the trial, we got to see additional footage from police body-cameras and nearby surveillance, showing Chauvin on top of Mr. Floyd for nine minutes and twenty seconds. Through this, Dr. Martin Tobin, a pulmonary critical care physician, was able to walk the jury through each exact moment that Floyd uttered his last words, took his last breath, and pumped his last heartbeat. Using freeze-frames from Chauvin’s own body cam, Dr. Tobin showed when Mr. Floyd was “literally trying to breathe with his fingers and knuckles.” This was Mr. Floyd’s only way to try to free his remaining, functioning lung, he explained.

Nine minutes and twenty seconds. Could you breathe with three big, angry grown men kneeling on top of you, wrangling to restrain you, shouting and demeaning you, pressing all of their weight down against you?

Even after Mr. Floyd begged for his momma, even after the man was unresponsive, and even still minutes after Floyd had lost a pulse, officer Chauvin knelt on his neck and shoulders. Chauvin knelt on the man’s neck even after paramedics had arrived and requested he make way. They had to pull the officer off of Floyd’s neck. The police initially called Mr. Floyd’s death “a medical incident during police interaction.” Yes, dear George, “it’s hard to love, there’s so much to hate.” Today, at least, there’s some hope to speak of.

April Showers: so many tears

What does April mean to you? April showers as the title would suggest, April Fools which I detest, or the beginning of winter’s rest? Today I am going to argue that April is the most criminogenic month of the year. No doubt, my colleagues and readers will disagree, but here goes….

What follows is discussion on three events which apart from their occurrence in the month of April are ostensibly unrelated. Nevertheless, scratch beneath the surface and you will see why they are so important to the development of my criminological understanding, forging the importance I place on social justice.

On 15 April 1912, RMS Titanic sank to the bottom of the sea, with more than 1,500 lost lives. We know the story reasonably well, even if just through film. Fewer people are aware that this tragedy led to inquiries on both sides of the Atlantic, as well, as Limitation of Liability Hearings. These acknowledged profound failings on the part of White Star and made recommendations primarily relating to lifeboats, staffing and structures of ships. Each of these were to be enshrined in law. Like many institutional inquiries these reports, thankfully digitised so anyone can read them, are very dry, neutral, inhumane documents. There is very little evidence of the human tragedy, instead there are questions and answers which focus on procedural and engineering matters. However, if you look carefully, there are glimpses of life at that time and criminological questions to be raised.

The table below is taken from the British Wreck Commissioners Inquiry Report and details both passengers and staff onboard RMS Titanic. This table allows us to do the maths, to see how many survived this ordeal. Here we can see the violence of social class, where the minority take precedence over the majority. For those on that ship and many others of that time, your experiences could only be mediated through a class based system. Yet when that ship went down, tragedy becomes the great equaliser.

On 15th April, 1989 fans did as they do (pandemics aside) every Saturday during the football season, they went to the game. On that sunny spring day, Liverpool Football Club were playing Nottingham Forest, both away from home and over 50,000 fans had travelled some distance to watch their team with family and friends. Tragically 96 of those fans died that day or shortly after. @anfieldbhoy has written a far more extensive piece on the Hillsborough Disaster and I don’t plan to revisit the details here. Nevertheless, as with RMS Titanic, questions were asked in relation to the loss of life and institutional or corporate failings which led to this tragedy. Currently it is not possible to access the Taylor Report due to ongoing investigation, but it makes for equally dry, neutral and inhuman, reading. It is hard to catch sight of 96 lives in pages dense with text, focused on answering questions that never quite focus on what survivors and families need. The Hillsborough Independent Panel [HIP] is far more focused on people as are the Inquests (also currently unavailable) which followed. Criminologically, HIP’s very independence takes it outside of powerful institutions. So whilst it can “speak truth to power” it has no ability to coerce answers from power or enforce change. For the survivors and family it brings some respite, some acknowledgement that what happened that day should have never have happened. However, for those individuals and wider society, there appears to be no semblance of justice, despite the passing of 32 years.

On 22 April 1993, Stephen Lawrence was murdered. He was the victim of a horrific, racially motivated, violent assault by a group of young white man. This much was known, immediately to his friend Duwayne Brooks, but was apparently not clear to the attending police officers. Instead, as became clear during the Stephen Lawrence Inquiry the police investigation was riddled with institutional racism from the outset. The Macpherson report (1999) tries extremely hard to keep focus on Stephen Lawrence as a human being, try to read the evidence given by Duwayne Brooks and Stephen’s parents without shedding a tear. However, much of the text is taken is taken up with procedural detail, arguments and denial. In 2012 two of the men who murdered Stephen Lawrence were found guilty and sentenced to be detained under Her Majesty’s pleasure (both were juveniles in 1993). Since 1999, when the report was published we’ve learnt even more about the police’s institutional racism and their continual attacks on Stephen’s family and friends designed to undermine and harm. So whilst institutions can be compelled to reflect upon their behaviour and coerced into recognising the need for change, for evolution, in reality this appears to be a surface activity. Criminologically, we recognise that Stephen was the victim of a brutal crime, some, but not all, of those that carried out the attack have been held accountable. Justice for Stephen Lawrence, albeit a long time coming, has been served to some degree. But what about his family? Traumatised by the loss of one of their own, a child who had been nurtured to adulthood, loved and respected, this is a family deserving of care and support. What about the institutions, the police, the government? It seems very much business as usual, despite the publication of Lammy (2017) and Williams (2018) which provide detailed accounts of the continual institutional racism within our society. Instead, we have the highly criticised Sewell Report (2021) which completely dismisses the very idea of institutional racism. I have not linked to this document, it is beneath contempt, but if you desperately want to read it, a simple google search will locate it.

In each of the cases above and many others, we know instinctively that something is fundamentally wrong. That what has happened has caused such great harm to individuals, families, communities, that it must surely be a crime. But a crime as we commonly understand it involves victim(s) and perpetrator(s). If the Classical School of Criminology is to be believed, it involves somebody making a deliberate choice to do harm to others to benefit ourselves. If there is a crime, somebody has to pay the price, whatever that may be in terms of punishment. We look to the institutions within our society; policing, the courts, the government for answers, but instead receive official inquiries that appear to explore everything but the important questions. As a society we do not seem keen to grapple with complexity, maybe it’s because we are frightened that our institutions will also turn against us?

The current government assures us that there will be an inquiry into their handling of the pandemic, that there will be some answers for the families of the 126,000 plus who have died due to Covid-19. They say this inquiry will come when the time is right, but right for who?

Maybe you can think of other reasons why April is a criminologically important month, or maybe you think there are other contenders? Either way, why not get in touch?

We are not the same…respectfully

Disclaimer: whilst I can appreciate that it’s Women’s History Month and it would be appropriate that we all come together in support of one another, especially in the notion of us vs them (men). However, I am undoubtedly compelled to talk about race in this matter, in all matters in that sense. I can only speak on the influence of the women who are around me and of women who look like me. Black women. So, to the lovely white girl on twitter who felt the need to express under my thread how disheartened she was by the racial separation of womanhood in feminism … from the bottom of my heart, I am not sorry.

Sometime last year I stumbled across a book called They Were Her Property: White Women as Slave Owners in the American South by the marvellous Stephanie Jones Rogers. The book protested against the belief that white women were delicate and passive bystanders to the slave economy due to masculine power in the 18th century. Instead, it explores the white supremacy of white women and the high level of protection they had which, which often led to the lynching and killing of many Black men and boys (Emmett Till, 1955). The book also looks at the role of enslaved wet nurses, as many white women perceived breastfeeding to be uncultured and therefore avoided it. However, while enslaved children were flourishing and healthy, many of the white babies were dying. As a result, Black mothers were forced to separate from their babies and dedicate their milk and attention to the babies of their mistresses.

Consequently, this led to the high rise of neglect and death of black babies as cow’s milk and dirty water was used as a substitute (Jones-Rogers, 2019). Furthermore, Rogers goes on to explain how the rape of Black women was used to ensure the supply of enslaved wet nurses. As you can imagine the book definitely does not sugar coat anything and I am struggling to finish it due to my own positionality in the subject. One thing for sure is that after learning about the book I was pretty much convinced that general feminism was not for me.

When I think about the capitalisation and intersectional exploitation that black women endured. I lightly emphasise the term ‘history’ when I say women’s history, because for Black women, it is timeless. It is ongoing. We see the same game play out in different forms. For example, the perception that white women are often the victims (Foley, et al., 1995) and therefore treated delicately, while Black women receive harsher/ longer sentences (Sharp, 2000). The high demand of Black women in human trafficking due to sexual stereotypes (Chong, 2014), the injustice in birth where Black women are five times more likely to die from pregnancy and childbirth than white women in the UK (University of Oxford, 2019) and the historical false narrative that Black women feel less pain than white women (Sartin, 2004, Hoffman et al, 2016).

So again, we are not the same…. Respectfully.

It is important for me to make clear that we are not the same, because we are viewed and treated differently than white women. We are not the same, because history tells us so. We are not the same, because the criminal justice system shows us so. We are not the same, because the welfare system and housing institutions show us so. We are not the same, because of racism.

This year’s women’s history month was more so about me learning and appreciating the Black women before me and around me. As I get older, it represents a subtle reminder that our fight is separate to much of the world. There is nothing wrong in acknowledging that, without having to feel like I am dismissing the fight of white women or the sole purpose of feminism in general. I am a Black feminist and to the many more lovely white women who may feel it’s unnecessary or who are disheartened by the racial separation of womanhood in feminism, I am truly, truly not sorry.

P.s to Nicole Thea, Sandra Bland, Toyin Salau, Blessing Olusegun, Belly Mujinga and Mary Agyeiwaa Agyapong. I am so sorry the system let down and even though you are not talked about enough, you will never be forgotten.

References:

Chong, N.G., (2014). Human trafficking and sex industry: Does ethnicity and race matter?. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 35(2), pp.196-213.

Foley, L.A., Evancic, C., Karnik, K., King, J. and Parks, A. (1995) Date rape: Effects of race of assailant and victim and gender of subjects on perceptions. Journal of Black Psychology, 21(1), pp.6-18.

Hoffman, K.M., Trawalter, S., Axt, J.R. and Oliver, M.N. (2016) Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(16), pp.4296-4301.

Jones-Rogers, S.E.(2019). They were her property: White women as slave owners in the American South. Yale University Press.

Sartin, J.S. (2004) J. Marion Sims, the father of gynecology: Hero or villain?. Southern medical journal, 97(5), pp.500-506.

Sharp, S.F., Braley, A. and Marcus-Mendoza, S. (2000) Focal concerns, race & sentencing of female drug offenders. Free Inquiry in Creative Sociology, 28(2), pp.3-16.

University of Oxford. (2019) NPEU News: Black women are five times more likely to die in childbirth than white women. Why? {Online}. Available from:https://www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/mbrrace-uk/news/1834-npeu-news-black-women-are-five-times-more-likely-to-die-in-childbirth-than-white-women-why {Accessed 29th March 2021}

Never Fear….Spring is almost here (part II)

A year ago, we left the campus and I wrote this blog entry, capturing my thoughts. The government had recently announced (what we now understand as the first) lockdown as a response to the growing global pandemic. Leading up to this date, most of us appeared to be unaware of the severity of the issue, despite increasing international news stories and an insightful blog from @drkukustr8talk describing the impact in Vietnam. In the days leading up to the lockdown life seemed to carry on as usual, @manosdaskalou and I had given a radio interview with the wonderful April Ventour-Griffiths for NLive, been presented with High Sheriff Awards for our prison module and had a wonderfully relaxing afternoon tea with Criminology colleagues. Even at the point of leaving campus, most of us thought it would be a matter of weeks, maybe a month, little did we know what was in store….At this stage, we are no closer to knowing what comes next, how do we return to our “normal lives” or should we be seeking a new normality.

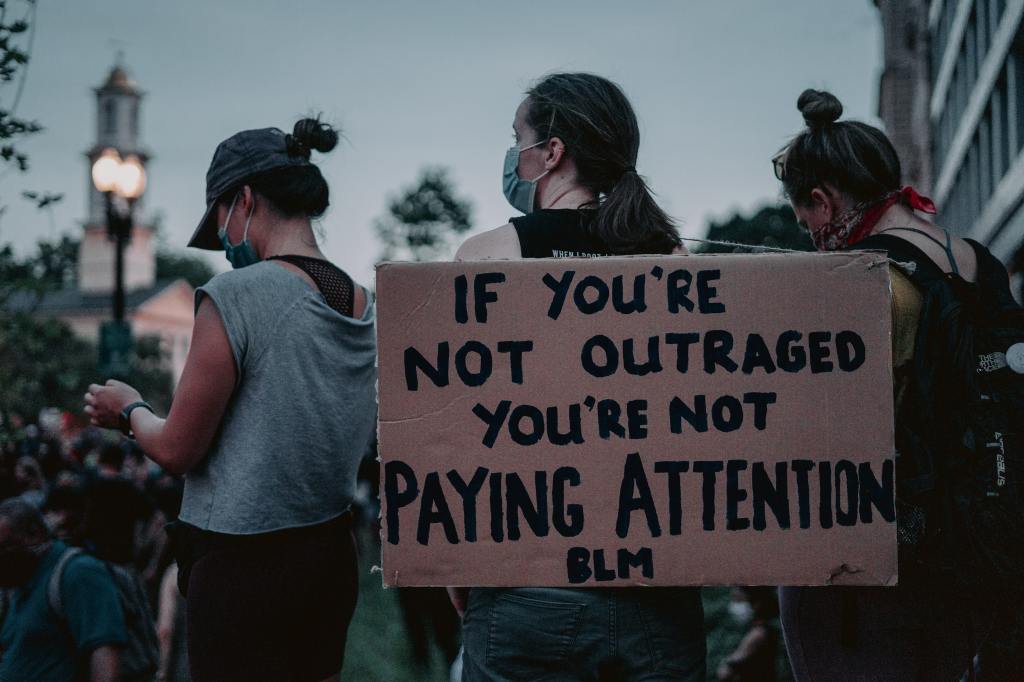

When I look back on my writing on 20 March 2020, it is full of fear, worry and uncertainty. There was early recognition that privilege and disadvantage was being revealed and that attitudes toward the NHS, shop workers and other services were encouraging, demonstrating kindness and empathy. All of these have continued in varying degrees throughout the past year. We’ve recognised the disproportionate impact of coronavirus on different communities, occupations and age groups. We’ve seen pensioners undertaking physically exhausting tasks to raise money for the tax payer funded NHS, we’ve seen children fed, also with tax payer funding, but only because a young footballer became involved. We’ve seen people marching in support of Black Lives Matter and holding vigils for women’s rights. For those who previously professed ignorance of disadvantage, injustice, poverty, racism, sexism and all of the other social problems which plague our society, there is no longer any escape from knowledge. It is as if a lid has been lifted on British society, showing us what has always been there. Now this spotlight has been turned on, there really is no excuse for any of us not to do so much better.

Since the start of the pandemic over 125,000 people in the UK have been killed by Coronavirus, well over 4.3 million globally. There is quotation, I understand often misattributed to Stalin, that states ‘The death of one man: this is a catastrophe. Hundreds of thousands of deaths: that is a statistic!’ However, each of these lives lost leaves a permanent void, for lovers, grandparents, parents, children, friends, colleagues and acquaintances. Each human touches so many people lives, whether we recognise at the time or not and so does their death. These ripples continue to spread out for decades, if not longer.

My maternal great grandmother died during the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918, leaving behind very small children, including my 5 year old nan. My nan rarely talked about her mother, or what happened afterwards, although I know she ended up in a children’s home on the Isle of Wight for a period of time. I regret not asking more questions while I had the chance. For obvious reasons, I never knew my maternal great grandmother, but her life and death has left a mark on my family. Motherless children who went onto become mothers and grandmothers themselves are missing those important family narratives that give a shape to individual lives. From my nan, I know my maternal great grandmother was German born and her husband, French. Beyond that my family history is unknown.

On Tuesday 23 March 2021 the charity Marie Curie has called for a National Day of Reflection to mark the collective loss the UK and indeed, the world has suffered. As you’ll know from my previous entries, here and here, I have reservations about displays of remembrance, not least doorstep claps. For me, there is an internal rather than external process of remembrance, an individual rather than collective reflection, on what we have been, and continue to go, through. Despite the ongoing tragedy, it is important to remember that nothing can cancel hope, no matter what, Spring is almost here and we will remember those past and present, who make our lives much richer simply by being them.

https://www.theartnewspaper.com/comment/a-message-from-david-hockney-do-remember-they-can-t-cancel-the-spring?fbclid=IwAR2iA8FWDHFu3fBQ067A7Hwm187IRfGVHcZf18p3hQzXJI8od_GGKQbUsQU

MLK: In his day-n-this day in 2021. #BlackedAsiaWithLove

In his day, they called Martin Luther King a thug. They said that he was disturbing the peace. They accused him of sedition, and jailed him on any charge they could find. The got him on any perceivable and inconceivable traffic violation. Mostly, the only charges they could find were loitering or disobeying a police order – do what I say, niggra! They convicted him to a 4-month sentence for a sit-in. They fined him and anyone in the movement for anything. You can’t imagine the trial/fiasco around his arrest for leading a bus boycott.

Sending his kids to school, peacefully.

Attending a comrade’s trial, peacefully. Loitering, peacefully. Sitting-in, peacefully. Driving, peacefully. Marching, peacefully. Preaching in the pulpit about the Prince of Peace, peacefully. Harassed, taunted, goaded, surveilled, bullied, bashed, arrested, convicted, abused by the police and their brethren among politicos – violently. Dear reader, please don’t find me pedantic by pointing out that this all sounds like 2020.

Here’s Dr. King’s full arrest record. He never once incited riots, yet they called him a thug. He never once missed an opportunity to call for calm, yet they said he was a looter. They made him a repeat offender, notoriously flaunting the law. Who was notoriously flaunting the law? The same sorts of folks who flaunted the law on January 6, 2021!

MLK grew up in the tradition of Black Liberation Theology, radically different from the individualist salvation and racism preached in white churches. King began to address this in a letter to white clergy, he wrote from a jail cell in bloody Birmingham. The pen is indeed mightier than the…cowardice of mobs and bombs.

Follow the drinking gourd

Dr. King understood that resistance is in our blood as strongly as the will to survive. Even with all of the stories I’ve heard from my elders, I still can’t imagine what it was like, even for my grandparents growing up picking cotton deep in the Jim Crow south. Yet, they resisted. And while I am sure that they feared white people their whole lives, they refused to study hate on them. Growing up, my grandparents had few choices in how they dealt with their white masters. Yet, they resisted hate. The roots of non-violence runs deep in our culture.

The roots of non-violent protest runs deep in American culture, but particularly so in terms of righting the legacy of our nation’s original sin: Slavery. In 1892, Homer Plessy was arrested for sitting in the white section of a street car in New Orleans. Four years later, the US Supreme Court upheld states’ right to segregate by race. This solidified Jim Crow at the highest court, and gave way to a host of racial segregation laws, policies and everyday practices that means virtually every aspect of life was unequal. This is the world into which Dr. King was born.

Culminating nearly a century after the Civil War the Civil Rights Movement worked to address the legacy of Slavery. It took that long, so dear reader, please do imagine a century of Jim Crow. Emancipation, then that.

Dr. King, Bayard Rustin and plenty, plenty others in their crew were repeatedly jailed and dismissed as agitators. Now, how many poor people sit in jail because in the New Jim Crow, they can’t afford the fines and fees, that means you pay for your own bondage. This is where your taxes go. Violence won’t solve this problem, but they won’t listen when you take a knee. They call you an agitator.

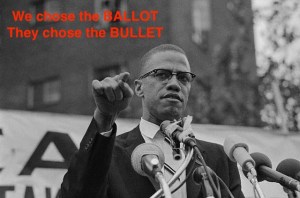

We chose the BALLOT they chose the BULLET

Dr. King used all his power to negotiate reconciliation, peacefully, yet he was gunned down and murdered, violently. Now, they advocate for their right to bear arms, knowing they’ve always been spurred to arm themselves in order to squash us (and not their own masters). They traded in whips and chains for guns and jails upon Emancipation. Now, their descendants are so twisted and confused about it that they claim not to know that’s also our blood shed and the Rebel flag, not just theirs. They still don’t get it. They are threatened by inclusion, perhaps fearing their own mediocracy, so they’d rather build a wall. In 2021, they were finally able to wave the Confederate Battle Flag in the halls of the US Capitol.

Their people fought and died for the independent right to bond and enslave us, yet now they speak of Dr. King like he’s some poster child for kneeling and praying for forgiveness in response to any atrocity they commit (even that kid who staged a massacre in a Black church was taken into custody, peacefully). Now, the same people call Dr. King a national hero in the same breath used to denounce those peacefully protesting for equity and justice today. For them, Black Lives do not Matter.

How should we honour “Our sheroes and heroes”?*

The British, so it seems, love a statue. Over the last few months we’ve seen Edward Colston’s toppled, Winston Churchill’s protected and Robert Baden-Powell’s moved to a place of safety. Much of the narrative around these particular statues (and others) has recently been contextualised in relation to the Black Lives Matter movement, as though nobody had ever criticised the subjects before. Colston, one time resident of Bristol and slave-trader was deemed worthy of commemoration some 174 years after his death and 62 years after the abolition of slavery. Likewise, one-time military man, accused of war crimes, homophobe and support for Nazism, Baden-Powell suddenly needed to be memorialised in 2008, almost 70 years after the second world world (and his death) and over 40 years since the passing of the Sexual Offences Act 1967. For both of these men profound problems were clear before the statues went up. Churchill, seen as a “hero” by many for his leadership in World War II has a very unsavoury history which is not difficult to locate in his own writings. His rehabilitation also ignores that his status for many of his contemporaries was as a warmonger. His passion for eugenics and his role in decisions to bomb Dresden, Hiroshima and Nagasaki can be wilfully swept under the carpet. Hero-worship is a dangerous game, it is also anti-intellectual. Churchill, like all of us, was a complex human, thus his legacy needs to be explored deeply and contextualised and only then can we decide what his place in his history should be. His statues and soundbites from speeches on repeat, do not allow for this.

Perhaps the most interesting part of this debate is to witness the inflamed defence of individuals who have a clearly documented history as slave owners, or as enthusiastic proclaimers of eugenic ideology, racism, homophobia and so on. As long as they have been ascribed “hero” status, we can ignore the rest of the seedy detail. We are told we need these statues, these heroic men, to remind us of our history….strangely Germany is able to reflect on its history, without statues of Hitler.

It seems as a nation we far prefer these individuals, responsible for so much misery, harm and violence in their lifetimes, than to present Black Britons and British Asians on a plinth. When we are reliant on South African President, Nelson Mandela to take up two of those London plinths, it is evident we have a serious racial imbalance in those “we” choose to commemorate.

Furthermore, the British appear to love an argument about statues, for instance, the criticism levelled at the artist Maggi Hambling’s statue to “Mother of Feminism” Mary Wollstencraft and Martin Jenning’s artistic tribute to Nurse Mary Seacole. For Wollstencroft, much of the furore has been directed at the artist, rather than the subject. There appears to be no irony in women attacking other women, in this case, Hambling, all in the name of supposed defence of The feminism. In the case of Mary Seacole, racially infused arguments from The Nightingale Society have suggested that this statue should not be in sight of that of Florence Nightingale. It seems that even when all important parties are long dead, it is deemed appropriate to use barely disguised racism to protect the stone image of your heroine. Important to remember that patriarchy has no gender. It is evident that criticism revolves around women’s representation in statuary, as well as women’s involvement in sculpture. When statues of men are said to outnumber those of women by around 16 to 1 (and that’s only when Queen Victoria is counted) it is evident we have a serious gender imbalance in those “we” choose to commemorate.

If there’s one thing the British love more than statues, it’s war commemorations. Think of the Cenotaph, standing proud in Whitehall, a memorial to ‘The Glorious Dead’ of firstly, World War I and latterly, British and Commonwealth military personnel have died in all conflicts.

Close by in Park Lane, we even have the imagination to create a memorial to Animals in War. We love to worship at these altars to untold misery and suffering, as if we could learn something important from them. Unfortunately, the most important message of “Never Again” is lost as we continue to thrust our military personnel and their deadly arsenal all over the world.

There is a strong argument for commemorating the war dead of all nations in the two World Wars. All sides, both central powers/axis and allies were comprised in the main of conscripted personnel. These were men and women that did not join the armed forces voluntarily, but were compelled by legislation to take up arms. With little time to consider or prepare, these people, all over the world, were thrust into life-threatening situations, with little or no choice. The Cenotaph and other war memorials mark this sacrifice and to some degree, acknowledge the experiences of those who served in a uniform that they did not consent to, without the compulsion of legislation. Unfortunately, civilians don’t feature so heavily in memorialisation, yet we know they experienced life-changing events which have repercussions even today. From children who were evacuated, to families who experienced fathers and husbands with short fuses, to those whose fear of hunger has never really left them, those experiences leave a mark.

To me, as a nation it appears that we don’t want to engage seriously with our history, preferring instead a white-washed, heteronormative, male-dominated, war-infused, saccharine sweet, version of events. But British people, both historically and contemporaneously, are a diverse and disparate group, good, bad and indifferent, so surely our statues should reflect this?

I recognise the violence which runs throughout British history, I learnt it, not through statues, but through books and oral testimony, through documentary and discussion. I also recognise that I have only begun to explore a history that silences so very many, making any historical narrative, partial, poignant and heavy with the missing voices. I recognise the heavy burden left by slavery, discrimination, war and other myriad violences, understanding the desire to commemorate and celebrate and tear down and replace.

What we need is a statue that recognises all of us, in all shapes and sizes, warts and all? We are living in a global pandemic, the death toll is currently standing at over 2.5 million. In the UK alone, the death toll stands at close to 100,000. Why not have a memorial with all those names; men, women, children, Black, white, Asian, mixed heritage, Muslim, Catholic, Buddhist, Christian, atheists, gay, straight, trans, lesbian, young, old and all those in between. People that have been coerced, through financial impetus, caring responsibility, career or vocation into dangerous spaces, who have not chosen to sacrifice their lives on the altar of bad decisions taken by governments and institutions (reminiscent of the world wars). Such a commemoration would be a way to recognise the profound impact on all of our lives, as drastic as any world war. It will recognise that you don’t have to wear a uniform or conform to a particular ideal to be of value to Britain and every person counts.

* Title borrowed from ‘Our sheroes and heroes’ (Maya Angelou ; interviewed by Susan Anderson in 1976)

I think that I am becoming one of THOSE Black people. #BlackenAsiaWithLove

I think that I am becoming one of THOSE Black people.

I think that I am becoming one of those Black people who doesn’t speak about race in mixed company, at least not casually, and certainly not in any space not specifically determined for such a conversation. If the invitation doesn’t say ‘race’ in the title, then I most assuredly won’t be bringing up sexism, racism nor classism, nor religious chauvinism – even if social status is evident and apparent by the time we get there. It’s too complicated, and I’ve been the unwitting sounding board too often for too many illiberals, or just folks who hadn’t ever really taken any time to (attempt to) put themselves in anyone else’s shoes – not even as a mental exercise to forward their own understanding of our world and its complexities.

Hurt people hurt people

I am an empath, and so shifting through perspectives is more organic to me than seems ‘normal’. Empaths more naturally take that Matrix-style 360-degree snapshot of any given scenario, distinct from neurotypical folks. I am also ‘a black man in a white world’, a gay man in a straight world, a Buddhist man in a Christian world, so I supposed I have made it a survival tactic to see the world through other’s eyes, knowing full well most hadn’t even considered I’d existed. It’s only other empaths who aren’t so surprised how we all got here across our differences. I have not had the luxury of surrounding myself with people just like me, and yet this has rarely made me feel unsafe.

This snapshot is also a means of connection: I like people and usually see similarities between people where they usually show me they’ve only ever seen differences. This isn’t to imply that I am colorblind or don’t see across differences. Naw, it’s that I am more interested in sharing hearts, no matter how deeply one has learned to bury and conceal theirs. Hence, I usually respond with “why” when told something ridiculously racist or sexist, and ask “how come you think that,” when something homophobic is said; and then I patiently listen. I genuinely want to know. I’ve observed that this response can throw people off balance, for they’ve become accustomed to people either joining in or ignoring their ignorance. Really, no one ever purely inquired how’d you become so hate-filled!?!

I wear my heart on my sleeve for I know how to recover from the constant assault and barrage of disconnection. Yes, it saddens me that so many have been so conditioned, and convinced for so long that we are so disconnected.

They want our RHYTHM but not our BLUES

Now, with my elite education and global aspirations, I often gain access to spaces that explicitly work to exclude people from any non-elite backgrounds. It’s not that I want to pass as anything other than myself, it’s just that I am often surrounded by folks who rarely seem to have considered that someone could – or would – simultaneously exist in a plethora of boxes. I can’t fit into any one box other than human. Yet, I used to try to fit in, to avoid standing out as a means to shield myself from the bullying or peering eyes and gossip as folks try to figure out in which box I reside – a classic tactic of projection.

I am a dark-skinned Black person with a nappy head and a stereotypical bubble butt. I neither bleach my skin nor straighten my hair, so I am identifiably Black up-close and from afar. I don’t even hide my body under baggy clothes, so even my silhouette is Black. I’ve lived, worked, studied and traveled in North America, western Europe, west Africa as well as north, south and southeast Asia, so I’ve taken 360-degree snapshots of radically different societies ‘seeing’ a Black man, and oh how radically different the reactions. I’m becoming one of those Black people who notices this, but won’t speak about race in mixed company because as an empath, one sees how defensive people become when raising race. I went through a phase where I would more readily speak about gender, then draw the parallels to race and class, for most folks can only handle one form of oppression at a time (fellow Audre Lorde fans may appreciate that pun).

Hello, my name is: Diversity.

I think that I am becoming one of those Black people who never questions people when they describe their backgrounds as ‘good’, when all they really mean is moneyed, racially and religiously homogenous. Many get all defensive when I reveal that my entire education was radically diverse by design, from second grade through my master’s. I know I had a “better” education than them because I was taught inclusion alongside people who were similar and different from me – and we went to each other’s homes.

I don’t look in the mirror and say ‘hey diversity’; I just see the face I was given, and do with it what I can. Yet, I have often been called upon to speak on behalf of many people. I offer my opinion, or relay my observations, and suddenly I am a spokesman for the gays, or the Blacks, rarely just me. So, what’s it like being on the inside of cultures of power? Darnit, I shan’t ask that either!

What’s the Capitol of Insurrection? #BlackenAsiaWithLove

A week ago, I was writing -hopefully – about the peaceful transition of power. I was thinking to myself that even if Georgia’s run-off election didn’t release the American senate from the hooves and cleaves of the CONservative right, that somehow, the world would be in a better state now that dialogue-oriented ‘liberals’ were leading the administrative cabinet. This week, however, I am writing about a failed coup d’etat in the United States.

Lynch mob

Much of American history is steeped in the struggle for freedom. To be clear: WE have never, ever been free in America. None of us. Sure, relative to where I sit right now in S.E. Asia, the fact that I am talking openly about politics, and speaking ill of other people’s nasty votes, attests to this relative freedom I enjoy just by having that bald eagle on my passport. The fact that it’s a national pass-time to be critical of power, all the while coveting it for myself, points to the hypocrisy with which each and every American struggles internally. It’s not that people of other nations don’t share this struggle, but it’s just that we Americans do this in the world’s richest, most ethnically diverse nation. And ‘the problem we all live with’ persists.

By signing the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln didn’t defeat white supremacy any more than the Declaration of Independence defeated tyranny and injustice. “With great power comes great responsibility,” goes the Spiderman mantra. Yet, here I am on my knees, in tears, crying for the death a of a democracy that’s been in decay ever since my people were brought to those shores in shackles, owned by those mentally enslaved by white-washed Jesus.

Unfortunately, it would be facile and naïve to pretend that this American moment isn’t painful. It hurt me, personally, to see the siege of our Capitol, live and in technicolor, more vivid than any dream I’ve dreamt or nightmare about this very scenario. And I have had both dreams and nightmares about the siege. My mother’s parents grew up southern, Black, poor and politically disenfranchised as a matter of everyday practice under Jim and Jane Crow. It’d would have been nothing for a lynch mob to tackle any negro attempting to vote. That was business as usual, even as they conscripted my grandfather into the army to go to Europe and fight Hitler. The irony has never, ever been lost on any of us.

Many days, in my daydreams, I’ve often wondered what it’d be like if a bunch of freedom-loving folks just stormed the Capitol and occupied the seats of power until the elected leaders conceded to formally grant our freedom. Yet, I would never want to see the mass graves they’d have to dig should any negro or negro-loving white person even gather to talk about storming the Capitol – let alone share plans and munitions. Besides, I am an earnest follower of non-violence and genuinely believe liberation is found therein. Instead, we’ve spent years – decades, nearly a century of recorded history – warning the world where white supremacy would lead us, if left unchecked. I’d be as rich as Jeff Bezos if I had a nickel for every time someone told me that racism was dead, and that I was dredging up hate by insisting we speak about it. Yet, here we are. Whatcha gonna do now?

2020: A Year on “Plague Island”

Last year in this blog, I argued that 2019 had been a year of violence. My colleague, @5teveh provided a gentle riposte, noting that whilst things had not been that good, they were perhaps not as bad as I had indicated. Looking back at both entries it is clear that my thoughts were well-evidenced, but it is @5teveh‘s rebuttal that has proved most prescient in respect of what was to come….

The year started off on a positive, personally and professionally, when both @manosdaskalou and I were nominated for Changemaker Awards. Although beaten by some very tough competition, shortly before leaving campus we were both awarded High Sheriff Awards, alongside our prison colleagues, for our module CRI3006 Beyond Justice. As colleagues and students will know, this module is taught entirely in prison to year 3 criminology students and their incarcerated peers. Unfortunately, the awards took place in the last week on campus, but we are hopeful that we can continue to work together in the near future.

Understandably much of our attention this year has been on Covid-19 and the changes it has wrought on individuals, communities, society and globally. Throughout this year, the Thoughts from the Criminology Team have documented the pandemic in a variety of different ways. From my very early thoughts, written in the panic of abandoning campus for the experience of lockdown to entries from @helentrinder @treventoursu @jesjames50 @cherylgardner2015 @5teveh @manosdaskalou @anfieldbhoy @samc0812 @drkukustr8talk @zeechee @saffrongarside @svr2727 @haleysread The blog has explored Covid-19 from a variety of different angles reflecting on the unprecedented experience of living through a pandemic. It is interesting to see how the situation and our understanding and responses have adapted over the past 9 months.

Alongside the serious materials, it was obvious very early on that we also needed to ensure some lightness for the team and our readers. With this in mind, early in the first lock down, we created the #CriminologyBookClub. We’re currently on our 8th novel and we’ve been highly critical of some of the texts ;), as well as fallen in love with others. However, I know I speak for my fellow members when I say this has offered some real respite for what’s going on around us.

Another early initiative was to invite all our bloggers to contribute an entry entitled #MyFavouriteThings. We ended up with over twenty entries (which you’ll find via the link) from the criminology team, students, as well as a our regular and occasional contributors. Surprisingly we learnt a lot about each other and about ourselves. The process of something as basic as writing down your favourite things, proved to be highly cathartic.

Whilst supporting each other in our learning community, we also didn’t forget our friends and colleagues in prison. Although, the focus has rightly been on the NHS and carers, the pandemic has hit the prison communities very hard. Technology can solve some of the issues of loneliness, but to be locked in a small room, far away from family and friends creates additional problems. For the men and the staff, the last 9 months has brought challenges never seen before. Although, we could not teach the module, we did our best, along with colleagues in Geography and the Vice Chancellor @npetfo, to provide quizzes and competitions to help pass the hours.

In June, the world was shocked by the killing of George Floyd in the USA. For many of us, this death was one in a long line of horrific killings of Black men and women, whereby society generally turned a blind eye. However, in the middle of a pandemic, the killing of George Floyd meant that people could not turn away from what was playing on every screen and every platform. This lead to a resurgence of interest in Black Lives Matter and an outpouring of statements by individuals, organisations, institutions and the State.

For a week in June, the Thoughts from the Criminology Team muted all their social media to make space for the #AmplifyMelanatedVoices initiative from Alishia McCullough and Jessica Wilson This was a tiny gesture in the grand scheme of things but refocused the team’s attention on making sure there is a space for anyone who wants to contribute.

Whether this new found interest in Black Lives Matters and discussions around diversity, racism, decolonisation and disproportionality continue, remains to be seen. Hopefully, the killing of George Floyd, alongside the profound evidence of privilege and need made evident by the pandemic, has provided a catalyst for change. One thing is clear, everyone knows now, we can no longer hide, there are no more excuses and we all can and must do better.

This year some old faces left for pastures new and we welcomed some new colleagues to the Criminology Team. If you haven’t already, you can read about our new (or, in some cases, not so new) team members’ – @jesjames50 @haleysread and @amycortvriend – academic journeys to becoming Lecturers in Criminology.

Finally, looking back over the last 12 months, certain themes catch my eye. Some of these are obvious, the pandemic and Black Lives Matter have occupied a lot of our minds. The focus has often been on high profile individuals – Captain Tom Moore, Joe Wickes, Marcus Rashford – but has also shone on teams/organisations/institutions such as the NHS, carers, shop workers, delivery drivers, the scientists working on the vaccines, the list goes on. Everyone has played a part, even if that is just by staying at home and out of the way, leaving space for those with a frontline role to play. Upon reflection it is evident that the over-riding themes (and why @5teveh was right last year) are ones of kindness, of going the extra mile, of trying to listen to each other, of reaching out to each other, acknowledging unfairness and privileges, recognising the huge loss of life and the impact of illness and bereavement and trying to make things a little better for all. Hope has become the default setting for all of us, hope that the pandemic will be over, alongside hopes that we can build a better world with its passing. It has also become extremely clear that critical thinking is at a premium during a pandemic, with competing narratives, contradictory evidence and uncertainty, testing all of our ability to cope with change and respond with humility and humanity.

There is no doubt 2020 has been an unprecedented year and one that will stay with us for ever in the collective memory. Going into 2021 it’s important that we remember to consider the positives and keep trying to do better. Hopefully, in 2021 we will get to celebrate Criminology’s 21st Birthday together

Remember to stay safe, strong and well and look out for yourself and others.