Home » Prison regime

Category Archives: Prison regime

A Criminal Called Bob

It was years ago that Bob was born in St. Mary’s Hospital. His mum delivered a relatively healthy baby that she called Robert, after her father despite kicking her out when he found out that she was pregnant from a casual encounter. Bob’s early memory was of a pain in the arm in a busy place he could not remember what it was. His mother was grabbing his arm an early sign that he was unwanted. He would remember many of these events becoming part of everyday life. He remembers one day a stern looking woman came to the place he was living with his mother and take him away. This was the last time he would ever see his mother; he was 5 or 6. A few years afterwards his mother will die from a bad heart. Later, he would find out it was drugs related.

The stern looking lady will take him to another place to live with a family. One of many that he would be placed in. At first, he tried to get to know the hosts but soon it became difficult to keep track. He also lost track of how many times he moved around. There were too many to count but the main memory was of fear going into a place he did not know to stay with people who treated him as an inconvenience. He owned nothing but a bin bag with a few clothes and people will always comment on how scruffy he looked. He remembers discovering some liquorice allsorts in a drawer with the kid he was sharing the room with. He cannot forget the beating he got for eating some of them. The host was very harsh, and they used the belt on him.

School was hell for Bob. As he moved from place to place the schools also changed. The introduction to the class was almost standard. Bob is joining us from so and so and although he lives in foster care, I hope you will be making him feel welcomed…and welcomed he was. The bullying was relentless so was the name calling and the attacks. On occasion he would meet an aloof man who was his “designated tutor”. His questions were abrupt and focused only if he was behaving, if he was making any trouble, if he did as was told. It was hardly ever about education or any of his needs. He remembers going to see him once with a bruised eye to be asked “what did you do?”

And he did a lot! Early on he learned that in order not to go hungry he must hide food away. If he was to meet a new person, he had to show them that he is cannot be taken for granted, he needed to show them he can handle himself. Sometime during his early teenage years his greeting gesture was a headbutt. Violence was a clear vehicle for communication. One person is down the other is up. This became a language he became prolific in. He could read a room quickly and in later years be able to assess the person opposite. If he can take him or not!

The truth that others kept talking about around him became a luxury and an unnecessary situation. Lying about things got him to avoid punishment and any consequences to any of his actions. The only problem was when he was get caught lying. The consequences were dire. So, what he needed to do was to become very good at it. He did. He could lie looking people straight in the eye and not even blink about it.

Later in life he discovered this was an amazing talent to possess. It was useful when he was stealing from shops, it was good when people asking him for the truth, it was profitable when his lies covered other people’s crimes. Before he turned 18, he was an experienced thief and a creative liar. His physique allowed him to take to violence should anyone was to question his “honesty”. When he was 15, he discovered that a combination of cider and acid gives him such a buzz. To mute his brain and to relax his body even for little was so welcomed. This habit became one of his most loyal relationships in his life.

In prison he didn’t go until he was 22 but he went to a young offender’s institution at the age of 17 for GBH. The “victim” was a former friend who stole some of his gear. That really angered him; even days after the event in court he was still outraged with the theft. He was still making threats that he will find him and kill him, in some very graphic descriptions! The court sought no other way but to send him away. From the age of 22 he would become a “frequent flyer” of the prison estate! A long list of different sentences ranging from everything on offer. Usually repeated in pattern; fine, community sentence, prison….and back again! By the time he was 35 he had been in prison for more than 8 years collectively. He did plenty of offender management courses and met a variety of probation and prison officers, well-meaning and not so good. Some tried to help, and others couldn’t care but all of them fade in the background.

Now at the ripe age of 45 he is out of the prison, and he is sofa surfing and claiming universal credit. He gets nothing because he has unpaid fines, so he is struggling financially. In prison he did a barista apprenticeship, but he cannot find any work. As it stands, he is very likely to be recalled back to prison, if the cold weather doesn’t claim him first.

In context, there are some lives that are never celebrated or commemorated. There are people who exist but virtually no one recognises their existence. Their lives are someone else’s inconvenience and in a society that prioritises individual achievement and progression they have none. Bob is a fictional character. His name and circumstances are made up but form part of a general criminological narrative that identifies criminality through the complexity of social circumstance.

#UONCriminologyClub: What should we do with an Offender? with Dr Paula Bowles

You will have seen from recent blog entries (including those from @manosdaskalou and @kayleighwillis21 that as part of Criminology 25th year at UON celebrations, the Criminology Team have been engaging with lots of different audiences. The most surprising of these is the creation of the #UONCriminologyClub for a group of home educated children aged between 10-15. The idea was first mooted by @saffrongarside (who students of CRI1009 Imagining Crime will remember as a guest speaker this year) who is a home educator. From that, #UONCriminologyClub was born.

As you know from last week’s entry @manosdaskalou provided the introductions and started our “crime busters” journey into Criminology. I picked up the next session where we started to explore offender motivations and society’s response to their criminal behaviour. To do so, we needed someone with lived experience of both crime and punishment to help focus our attention. Enter Feathers McGraw!!!

At first the “crime busters” came out with all the myths: “master criminal” and “evil mastermind” were just two of the epithets applied to our offender. Both of which fit well into populist discourse around crime, but neither is particularly helpful for criminological study, But slowly and surely, they began to consider what he had done (or rather attempted to do) and why he might be motivated to do such things (attempted theft of a precious jewel). Discussion was fast flowing, lots of ideas, lots of questions, lots of respectful disagreement, as well as some consensus. If you don’t believe me, have a look at what Atticus and had to say!

We had another excellent criminology session this week, this time with Dr Paula Bowles. I think we all had a lot of fun, I personally could have enjoyed double or triple the session time. Dr Bowles was engaging, fun and unpretentious, making Criminology accessible to us whilst still covering a lot of interesting and complex subjects. We discussed so many different aspects of serious crime and moral and ethical questions about punishment and the treatment of criminals. During the session, we went into some very deep topics and managed to cover many big ideas. It was great that everyone was involved and had a lot to say. You might not necessarily guess from what I’ve said so far, how we got talking about Criminology in this way. It was all through the new Aardman animations film Wallace and Gromit: Vengeance Most Fowl and the cheeky little penguin or is it just a chicken? Feathers McGraw. Whether he is a chicken or a penguin, he gave us a lot to discuss such as whether his trial was fair or not since he can’t talk, if the zoo could really be counted as a prison and, if so was he allowed to be sent there without a trial? Deep ethical questions around an animation. Just like last time it was a fun and engaging lesson that made me want to learn more and more and I can’t wait for next time. (Atticus, 14)

What emerged was a nuanced and empathetic understanding of some key criminological debates and questions, albeit without the jargon so beloved of social scientists: nature vs. nurture, coercion and manipulation of the vulnerable, the importance of human rights, the role of the criminal justice system, the part played by the media, the impetus to punish to name but a few. Additionally, a deep philosophical question arose as to whether or not Aardman’s portrayal of Feathers’ confinement in a zoo, meant that as a society we treat animals as though they are criminals, or criminals as though they are animals. We are all still pondering this particular question…. After deciding as group that the most important thing was for Feathers to stop his deviant behaviour, discussions inevitably moved on to deciding how this could be achieved. At this point, I will hand over to our “crime busters”!

What to do with Feathers McGraw?

At first, I thought that maybe we should make prison a better place so that he would feel the need to escape less. It wouldn’t have to be something massive but just maybe some better furniture or more entertainment. Also maybe make the security better so that it would be harder to break out. If we imagine the zoo as the prison, animals usually stay in the zoo for their life so they must have done some very bad stuff to deserve a life sentence! Is it safe to have dangerous animals so close to humans? Feathers McGraw might get influenced by the other prisoners and instead of getting better he might get more criminal ideas. I believe there should be a purpose-built prison for the more dangerous criminals, so they are kept away from the humans and the non-violent criminals. in this case is Feathers considered a violent or non-violent criminal? Even though he hasn’t killed anyone, he has abused them, tried to harm them, hacked into Wallace’s computer, vandalised gardens through the Norbots, and stole the jewel. So, I think we should get a restraining order against Feathers McGraw to stop him from seeing Wallace and Gromit. I also think we should invest in therapy for Feathers to help him realise that he doesn’t need to own the jewel to enjoy it, what would he even do with it?! Maybe socializing could also help to maybe take his mind of doing criminal things. He always seems alone and sad. I’m not sure whether he will be able to change his ways or not but I think we should do the best we can to. (Paisley, 10)

I think in order to stop Feathers McGraw’s criminal behaviour, he should go to prison but while he is there, he should have some lessons on how to be good, how to make friends, how to become a successful businessman (or penguin!), how to travel around on public transport, what the law includes and what the punishments there are for breaking it etc. I also think it’s important to make the prisons hospitable so that he feels like they do care about him because otherwise it might fuel anger and make him want to steal more diamonds. At the same time though, it should not be too nice so that he’ll think that stealing is great, because if you don’t get caught, then you keep whatever you stole and if you do get caught then it doesn’t matter because you will end up staying in a luxury cell with silky soft blankets.

After he is released from prison, I would suggest he would be held under house arrest for 2-3 months. He will live with Wallace and Gromit and he will receive a weekly allowance of £200. With this money, he will spend:

£100 – Feathers will pay Wallace and Gromit rent each week,

£15-he will pay for his own clothes,

£5-phone calls,

£10-public transport,

£35-food,

£5-education,

£15-hygiene,

£15- socialising and misc.

During this time, Feathers could also be home educated in the subjects of Maths, English etc. He should have a schedule so he will learn how to manage his time effectively and eventually should be able to manage his timewithouta schedule. The reason for this is because when Feathers was in prison, he was told what to do every day and at what time he would do it. He now needs to learn how to make those decisions by himself. This would mean when his house arrest is finished, he can go out into the real world and live happy life without breaking the law or stealing. (Linus, 13)

I think that once Feathers McGraw has been captured any money that he has on him will be taken away as well as any disguises that he has and if he still has any belongings left they will be checked to see whether he can have them. After that he should go to a proper prison and not a Zoo, then stay there for 3 months. Once a week, while he is in prison a group of ten penguins will be brought in so that he can be socialised and learn manners and good behaviour from them. However they will be supervised to make sure that they don’t come up with plans to escape. After that he will live with a police officer for 3 years and not leave the house unless a responsible and trustworthy adult accompanies him until he becomes trustworthy himself. He will be taught at the police officers house by a tutor because if he went to school he might run away. Feathers McGraw will have a weekly allowance of £460 that is funded by the government as he won’t have any money. Any money that was taken away from him will be given back in this time. Any money left over will be put into his savings account or used for something else if the money couldn’t quite cover it.

In one week he will give

£60 for fish and food

£10 for travel

£50 for clothing but it will be checked to make sure that it isn’t a disguise.

£80 for the police officer that looking after him

£15 for necessities (tooth brush, tooth paste, face cloth etc…)

£70 for his tutor

£55 for education supplies

£20 will be put in a savings account for when he lives by himself again.

And £100 for some therapy

After 1 year if the police officer looking after him thinks that he’s trustworthy enough then he can get a job and use £40 pounds a week (if he earns manages to earn that much.) as he likes and the rest of it will be put into his savings account. Feathers McGraw will only be allowed to do certain jobs for example, He couldn’t be a police officer in case he steals something that he’s guarding, He also couldn’t be a prison guard in case he helped someone escape etc… If at any point he commits another crime he will lose his freedom and his job and will be confined to the house and garden. When he lives by himself again he will have to do community service for 1 month. (Liv, 11).

Feathers McGraw has committed many crimes, some of which include attempted theft, abuse towards Wallace and Gromit, and prison break.

Here are some ideas of things that we can do to stop him from reoffending:

Immediate action:

A restraining order is to be put in place so he can’t come within 50m of Wallace and Gromit, for their protection both physical and mental. Penguins live for up to 20 years so seeing as he is portrayed as being an adult, my guess is he is around 10 years old. His sentence should be limited to 2 years in prison. Whilst serving his sentence he should be given a laptop (with settings so that he can’t use it to hack) so he can write, watch videos, play games and learn stuff.

Longer term solutions:

When Feathers gets out he will be banned from seeing the gem in museums so there will be less chance of him stelling it. He also will be given some job options to help him get started in his career. His first job won’t be front facing so Wallace and Gromit won’t have to be worried and they will get to say no to any job Feathers tries to get. If he reoffends, he will be taken to court where his sentence will be a minimum of 5 years in prison.

Rehabilitation:

I think Feathers should be given rehabilitation in several different forms, some sneakier than others! One of these forms is probation: penguins which are trained probation officers who will speak to him and try to say that crime is not cool. To him they will look like normal penguins, he won’t know that they have had training. He also should be offered job experience so he can earn a prison currency which he can use to buy upgrades for his cell (for example a better bed, bigger tv, headphones, an mp3 player and songs for said mp3 player) to give him a chance to get a job in the future. (Quinn, 12)

The “crime busters” comments above came after reflecting on our session, their input demonstrates their serious and earnest attempt to resolve an extremely complex issue, which many of the greatest minds in Criminology have battled with for the last two centuries. They may seem very young to deal with a discipline often perceived as dark, but they show us an essential truth about Criminology, it is always hopeful, always focused on what could be, instead of tolerating what we have.

Exploring the National Museum of Justice: A Journey Through History and Justice

As Programme Leader for BA Law with Criminology, I was excited to be offered the opportunity to attend the National Museum of Justice trip with the Criminology Team which took place at the back end of last year. I imagine, that when most of us think about justice, the first thing that springs to mind are courthouses filled with judges, lawyers, and juries deliberating the fates of those before them. However, the fact is that the concept of justice stretches far beyond the courtroom, encompassing a rich tapestry of history, culture, and education. One such embodiment of this multifaceted theme is the National Museum of Justice, a unique and thought-provoking attraction located in Nottingham. This blog takes you on a journey through its historical significance, exhibits, and the essential lessons it imparts and reinforces about justice and society.

A Historical Overview

The National Museum of Justice is housed in the Old Crown Court and the former Nottinghamshire County Gaol, which date back to the 18th century. This venue has witnessed a myriad of legal proceedings, from the trials of infamous criminals to the day-to-day workings of the justice system. For instance, it has seen trials of notable criminals, including the infamous Nottinghamshire smuggler, and it played a role during the turbulent times of the 19th century when debates around prison reform gained momentum. You can read about Richard Thomas Parker, the last man to be publicly executed and who was hanged outside the building here. The building itself is steeped in decade upon decade of history, with its architecture reflecting the evolution of legal practices over the centuries. For example, High Pavement and the spot where the gallows once stood.

By visiting the museum, it is possible to trace the origins of the British legal system, exploring how societal values and norms have shaped the laws we live by today. The National Museum of Justice serves as a reminder that justice is not a static concept; it evolves as society changes, adapting to new challenges and perspectives. For example, one of my favourite exhibits was the bench from Bow Street Magistrates Court. The same bench where defendants like Oscar Wilde, Mick Jagger and the Suffragettes would have sat on during each of their famous trials. This bench has witnessed everything from defendants being accused of hacking into USA Government computers (Gary McKinnon), Gross Indecency (Oscar Wilde), Libel (Jeffrey Archer), Inciting a Riot (Emmeline Pankhurst) as well as Assaulting a Police Officer (Miss Dynamite).

Understanding this rich history invites visitors to contextualize the legal system and appreciate the ongoing struggle for a just society.

Engaging Exhibits

The National Museum of Justice is more than just a museum; it is an interactive experience that invites visitors to engage with the past. The exhibits are thoughtfully curated to provide a comprehensive understanding of the legal system and its historical context. Among the highlights are:

1. The Criminal Courtroom: Step into the courtroom where real trials were once held. Here, visitors can learn about the roles of various courtroom participants, such as the judge, jury, and barristers. This is the same room that the Criminology staff and students gathered in at the end of the day to share our reflections on what we had learned from our trip. Most students admitted that it had reinforced their belief that our system of justice had not really changed over the centuries in that marginalised communities still were not dealt with fairly.

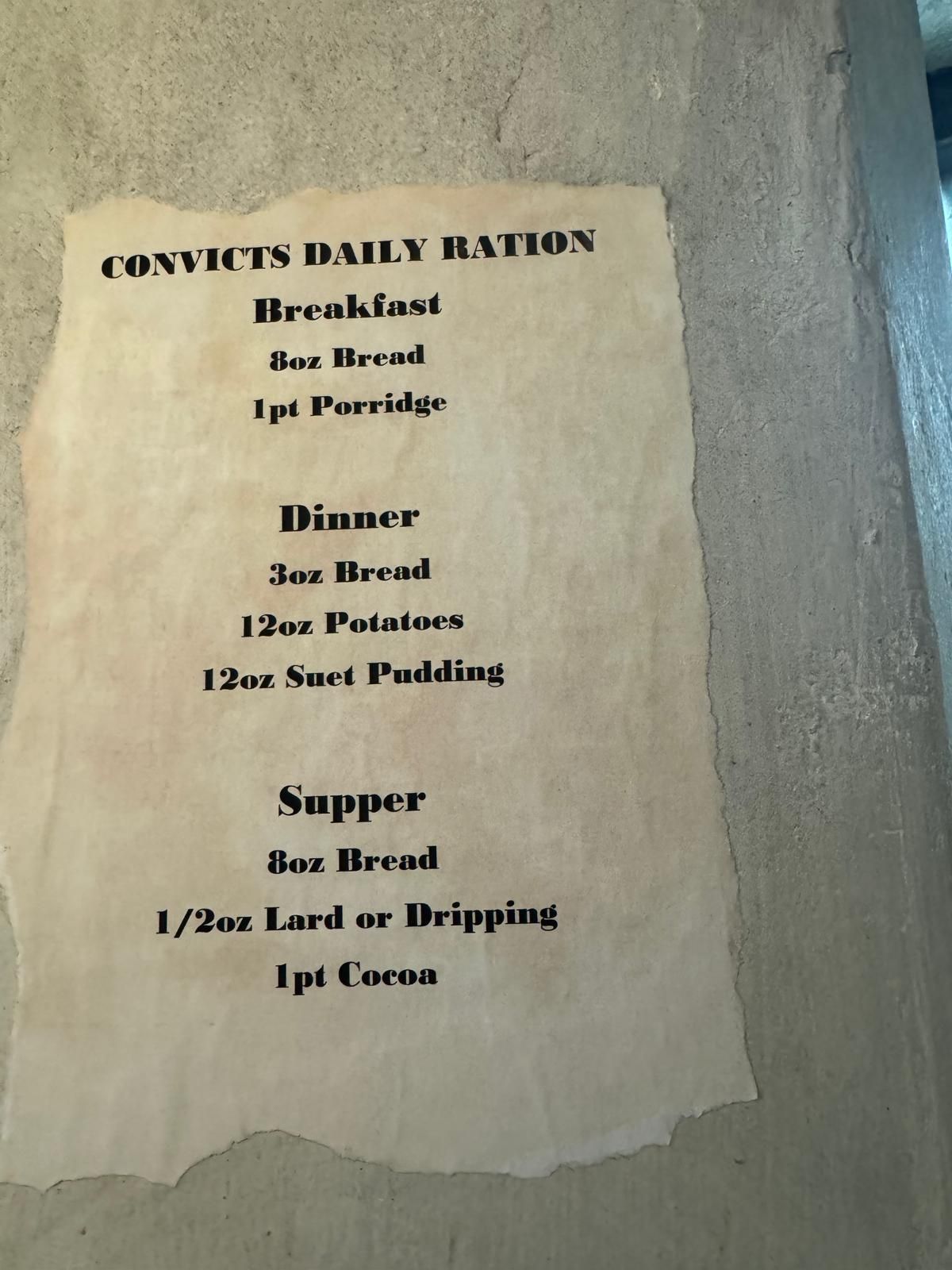

2. The Gaol: We delved into the grim reality of life in prison during the Georgian and Victorian eras. The gaol section of the gallery offers a sobering look at the conditions inmates faced, emphasizing the societal implications of punishment and rehabilitation. For example, every prisoner had to pay for his/ her own food and once their sentence was up, they would not be allowed to leave the prison unless all payments were up to date. The stark conditions depicted in this exhibit encourage reflections on the evolution of prison systems and the ongoing debates surrounding rehabilitation versus punishment. Eventually, in prisons, women were taught skills such as sewing and reading which it was hoped may better their chances of a successful life in society post release. This was an evolution within the prison system and a step towards rehabilitation of offenders rather than punishment.

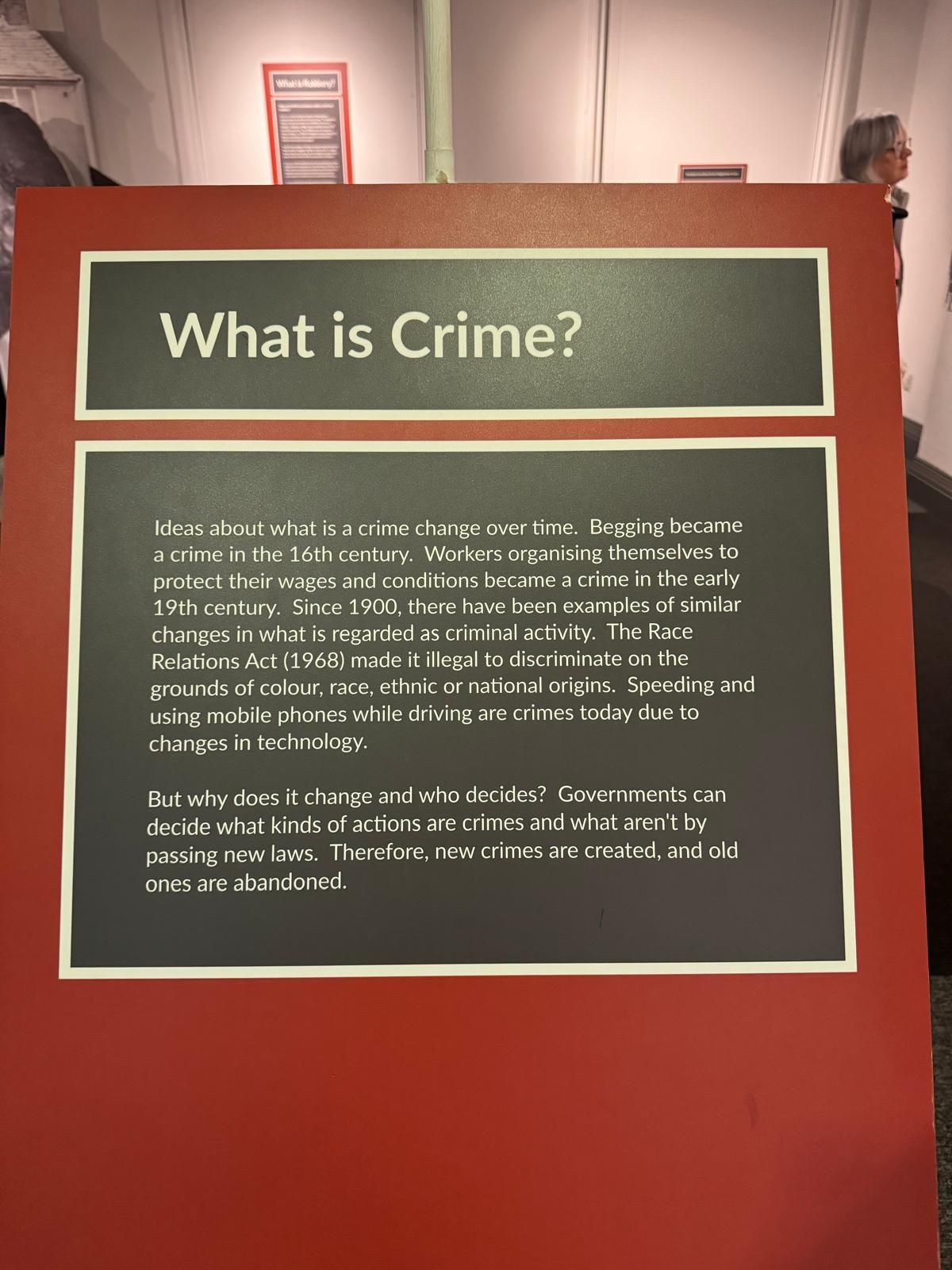

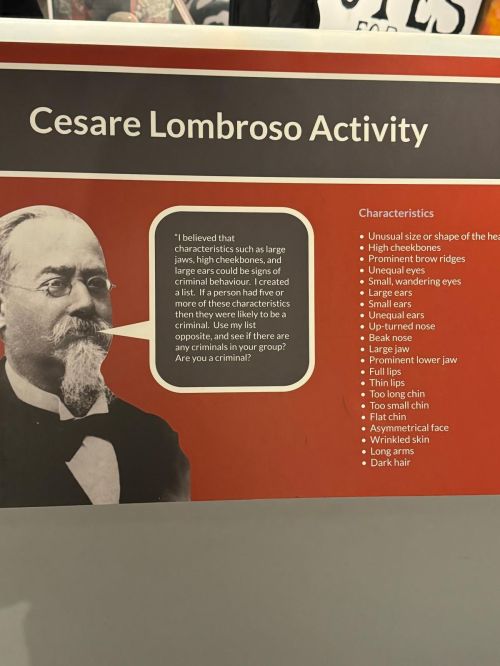

3. The Crime and Punishment Exhibit: This exhibit examines the relationship between crime and society, showcasing the changing perceptions of criminal behaviour over time. For example, one famous Criminologist of the day Cesare Lombroso, once believed that it was possible to spot a criminal based on their physical appearance such as high cheekbones, small ears, big ears or indeed even unequal ears. Since I was not familiar with Lombroso or his work, I enquired with the Criminology department as to studies that he used to reach the above conclusions. Although I believe he did carry out some ‘chaotic’ studies, it really reminded me that it is possible to make statistics say whatever it is you want them to say. This is the same point in relation to the law generally. As a lawyer I can make the law essentially say whatever I want it to say in the way I construct my arguments and the sources I include. Overall, The Inclusions of such exhibits raises and attempts to tackle difficult questions about personal and societal morality, justice, and the impact of societal norms on individual actions. By examining such leading theories of the time and their societal reactions, the exhibit encourages visitors to consider the broader implications of crime and the necessity of reform within the justice system. Do you think that today, deciding whether someone is a criminal based on their physical appearance would be acceptable? Do we in fact still do this? If we do, then we have not learned the lessons from history or really moved on from Cesare Lombroso.

Lessons on Justice and Society

The National Museum of Justice is not merely a historical site; it also serves as a platform for discussions about contemporary issues related to justice. Through its exhibits and programs, our group was invited to reflect on essentially- The Evolution of Justice: Understanding how laws have changed (or not!) over time helps us appreciate the progress (or not!) made in human rights and justice and with particular reference to women. It also encourages us to consider what changes may still be needed. For example, we were incredibly privileged to be able to access the archives at the museum and handle real primary source materials. We, through official records followed the journey of some women and girls who had been sent to reform schools and prisons. Some were given extremely long sentences for perhaps stealing a loaf of bread or reel of cotton. It seemed to me that just like today, there it was- the huge link between poverty and crime. Yet, what have we done about this in over two or three hundred years? This focus on historical cases illustrates the importance of learning from the past to inform present and future legal practices.

– The Importance of Fair Trials: The gallery emphasizes the significance of due process and the presumption of innocence, reminding us that justice must be impartial and equitable. In a world where public opinion can often sway perceptions of guilt or innocence, this reminder is particularly pertinent. The National Museum of Justice underscores the critical role that fair trials play in maintaining the integrity of the legal system. For example, if you were identified as a potential criminal by Cesare Lombroso (who I referred to above) then you were probably not going to get a fair trial versus an individual who had none of the characteristics referred to by his studies.

– Societal Responsibility: The exhibits prompt discussions about the role of society in shaping laws and the collective responsibility we all share in creating a just environment. The National Museum of Justice encourages visitors to think about their own roles in advocating for justice, equality, and reform. It highlights that justice is not solely the responsibility of legal professionals but also of the community at large.

– Ethics and Morality: The museum offers a platform to explore ethical dilemmas and moral questions surrounding justice. Engaging with historical cases can lead to discussions about right and wrong, prompting visitors to consider their own beliefs and biases regarding justice.

Conclusion

The National Museum of Justice in Nottingham is a remarkable destination that beautifully intertwines history, education, and advocacy for justice. By exploring its rich exhibits and engaging with its thought-provoking themes, visitors gain a deeper understanding of the complexities surrounding justice and its vital role in society. Whether you are a history buff, a legal enthusiast, a Criminologist or simply curious about the workings of justice, the National Museum of Justice offers a captivating journey that will leave you enlightened and inspired.

As we navigate the complexities of the modern world, it is essential to remember the lessons of the past and continue striving for a fair and just society for all. The National Museum of Justice stands as a powerful testament to the ongoing quest for justice, inviting us all to be active participants in that journey. In doing so, we honour the legacy of those who have fought for justice throughout history and commit ourselves to ensuring that the principles of fairness and equity remain at the forefront of our society. Sitting on that same bench that Emmeline Pankhurst once sat really reminded me of why I initially studied law.

The main thought that I was left with as I left the museum was that justice is not just a concept; it is a lived experience that we all contribute to shaping.

Criminology for all (including children and penguins)!

As a wise woman once wrote on this blog, Criminology is everywhere! a statement I wholeheartedly agree with, certainly my latest module Imagining Crime has this mantra at its heart. This Christmas, I did not watch much television, far more important things to do, including spending time with family and catching up on reading. But there was one film I could not miss! I should add a disclaimer here, I’m a huge fan of Wallace and Gromit, so it should come as no surprise, that I made sure I was sitting very comfortably for Wallace & Gromit: Vengeance Most Fowl. The timing of the broadcast, as well as it’s age rating (PG), clearly indicate that the film is designed for family viewing, and even the smallest members can find something to enjoy in the bright colours and funny looking characters. However, there is something far darker hidden in plain sight.

All of Aardman’s Wallace and Gromit animations contain criminological themes, think sheep rustling, serial (or should that be cereal) murder, and of course the original theft of the blue diamond and this latest outing was no different. As a team we talk a lot about Public Criminology, and for those who have never studied the discipline, there is no better place to start…. If you don’t believe me, let’s have a look at some of the criminological themes explored in the film:

Sentencing Practice

In 1993, Feathers McGraw (pictured above) was sent to prison (zoo) for life for his foiled attempt to steal the blue diamond (see The Wrong Trousers for more detail). If we consider murder carries a mandatory life sentence and theft a maximum of seven years incarceration, it looks like our penguin offender has been the victim of a serious miscarriage of justice. No wonder he looks so cross!

Policing Culture

In Vengeance Most Fowl we are reacquainted with Chief Inspector Mcintyre (see The Curse of the Were-Rabbit for more detail) and meet PC Mukherjee, one an experienced copper and the other a rookie, fresh from her training. Leaving aside the size of the police force and the diversity reflected in the team (certainly not a reflection of policing in England and Wales), there is plenty more to explore. For example, the dismissive behaviour of Mcintyre toward Mukherjee’s training. learning is not enough, she must focus on developing a “copper’s gut”. Mukherjee also needs to show reverence toward her boss and is regularly criticised for overstepping the mark, for instance by filling the station with Wallace’s inventions. There is also the underlying message that the Chief Inspector is convinced of Wallace’s guilt and therefore, evidence that points away from should be ignored. Despite this Mukherjee retains her enthusiasm for policing, stays true to her training and remains alert to all possibilities.

Prison Regime

The facility in which Feathers McGraw is incarcerated is bleak, like many of our Victorian prisons still in use (there are currently 32 in England and Wales). He has no bedding, no opportunities to engage in meaningful activities and appears to be subjected to solitary confinement. No wonder he has plenty of time and energy to focus on escape and vengeance! We hear the fear in the prison guards voice, as well as the disparaging comments directed toward the prisoner. All in all, what we see is a brutal regime designed to crush the offender. What is surprising is that Feathers McGraw still has capacity to plot and scheme after 31 years of captivity….

Mitigating Factors

Whilst Feathers McGraw may be the mastermind, from prison he is unable to do a great deal for himself. He gets round this by hacking into the robot gnome, Norbot. But what of Norbot’s free will, so beloved of Classical Criminology? Should he be held culpable for his role or does McGraw’s coercion and control, renders his part passive? Without, Norbot (and his clones), no crime could be committed, but do the mitigating factors excuse his/their behaviour? Questions like this occur within the criminal justice system on a regular basis, admittedly not involving robot gnomes, but the part played in criminality by mental illness, drug use, and the exploitation of children and other vulnerable people.

And finally:

Above are just some of the criminological themes I have identified, but there are many others, not least what appears to be Domestic Abuse, primarily coercive control, in Wallace and Gromit’s household. I also have not touched upon the implicit commentary around technology’s (including AI’s) tendency toward homogeneity. All of these will keep for classroom discussions when we get back to campus next week 🙂

Black History Month 2024

We have entered Black History Month (BHM), and whilst to some it is clear that Black history isn’t and shouldn’t be confined to one month a year, it would be unwise not to take advantage of this month to educate, raise awareness and celebrate Blackness, Black culture.

This year the Criminology department is planning a few events designed to be fun, informative and interesting.

One event the department will hold is a BHM quiz, designed to be fun and test your knowledge. Work individually or in groups, the choice is yours. The quiz will be held on the 17th October in The Hide (4th floor) in the Learning Hub from 4.30-6pm.

The second event will draw on the theme of this year’s BHM which is all about reclaiming narratives. In the exhibition area (ground floor of the Learning Hub) we will be presenting a number of visual narratives. I will be displaying a series of identity trees from Black women that I interviewed as part of my PhD research on Black women in English prisons. With a focus on race and gender, these identity trees represent a snapshot of the lives and lived experiences of these women prior to imprisonment. The trees also highlight the hopes and resilience of these women. This event will be held on the 31st October between 4.30-6pm. Please do walk through and have a look at the trees and ask questions. The event is designed for you to spend as little or as much time as you would like, whether it is a brief look or a longer discussion your presence is much welcomed!

If you would like to be part of this event, whether that is sharing your own research (staff and students), or if you would like to use the space to share your own narrative as a Black individual please get in contact by the 21st October by emailing angela.charles@northampton.ac.uk or criminology@northampton.ac.uk

Lastly, I would like to put a spotlight on a few academics to maybe read up on this month and beyond:

A few suggestions for important discussions on Black feminism and intersectionality:

A few academics with powerful and interesting research that proved very important in my PhD research:

A visual walk around a panopticon prison in the city of “Brotherly Love”

Conferences…people even within academia have views on them. This year the American Society of Criminology hosted its annual meeting in Philadelphia. In the conference we had the opportunity to talk about course development and the pedagogies in criminology. Outside the conference we visited Eastern State Penitentiary one of the original panopticon prisons…now a decaying museum on penal philosophy and policy.

The bleak corridors of a panopticon prison

the walls are closing in and there is only light from above

these cells smell of decay; they were the last residence of those condemned to death

the old greenhouse; now a glass/concrete structure…then a place to plant flowers. Even in the darkest places life finds a way to persevere

isolation: a torture within an institution of violence. The people coming out will be forever scared as time leaves the harshest wounds

a place of worship: for some the only companion to abject desperation; for those who did not lose their minds or try to end their lives; faith kept them at least alive.

the yard is monitored by the guards at the core; the chained prisoners will walk outside or get some exercise but only if they behave. To be outside in here is a privilege

the corridors look identical; you become disoriented and disillusioned

everything here conjures images of pain

an ostentatious building, build back in the 19th century to lock in criminals. It housed a new principled idea, a new system on penal reform. the first penitentiary of its kind. Nonetheless it never stopped being an institution of oppression…it closed in 1970.

The role of the criminologist (among others) is to explain, analyse and discuss our responses to crime, the systems we use and the strategies employed. So before a friendly neighbour tells you that sending people to an island or arming the police with guns or giving juveniles harsher penalties, they better talk to a criminologist first.

As a final thought, I leave you with this…there are people who left the prison broken but there are those who died in this prison. Eleven people tried to escape but were recaptured. Once you are sent down, the prison owns you.

Reproductive Healthcare Ramblings

Reproductive health in England and Wales is a shambles: particularly for women and people who menstruate. The failings start early, where, as with most things, stereotypes and ‘norms’ are enforced upon children from GPs, schools, from parents/guardians who have experienced worse, or who do not know any different, which keep children from speaking up. These standards and stereotypes come from a male dominated health care system especially in relation to gynaecology, and our patriarchal society silences children without the children even realising they are being silenced. As a child, you are expected to go about your daily routine, sit your exams, look after your siblings, represent the school at the tournament of the week, and do all this while, for some, bleeding, cramping, being fatigued but not be expected to talk about it. After all, you are told time and time again: it’s normal.

Moving through life, women and people who menstruate face similar stigma, standards, assumptions during adulthood as they faced during childhood. There is more awareness now of endometriosis, adenomyosis, uterine fibroids, Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Condition (PCOS) to name but a few. But women and people who menstruate report feelings of being gaslighted by [male] gynaecologists, encouraged to have children in order to regulate their hormones (pregnancy and childbirth comes with a whole new set of healthcare problems and conditions), to take the contraceptive pill and deal with the migraines, mood swings, weight gain and depression which many women and girls report. Some of the above chronic illnesses impact fertility, so ‘try for a baby’ is not an easy, or even a wanted path. Diagnosis is also complex: for example a diagnosis for endometriosis takes on average 8 years (Endometriosisuk, 2023), and can only be confirmed with surgery. That relies on women and people who menstruate going to their GP, reporting their symptoms, listening to the ‘have you tried the pill’ or ‘having a baby will help manage your symptoms’: which relies on trust. Not everyone trusts the NHS, not everyone feels comfortable being dismissed by a nurse, or GP or then their gynaecologist. Especially when a number of these illnesses are framed and seen as a white-woman illness. Communities of women and people who menstruate remain hidden, dealing with the stigma and isolation that our reproductive health system carries in England and Wales. And this is not a new issue.

The reproductive healthcare for women and people who menstruate is dire. Just ask anyone who has experienced it. What then is it like for women in prison? The pains of imprisonment are well documented: deprivation of goods, loss of liberty, institutionalisation, no security, depreciation of mental health (Sykes, 1958; Carlen, 1983). The gendered pains, fears and harms less so, but we know women in prison are fearful about the deterioration of relationships (especially with children), lack of facilities to support new mothers, physical and sexual abuse, and poor mental and physical health support including reproductive health. The poor reproductive healthcare available to women and people who menstruate within society, is a grade above what is available in prisons. These women are quite literally isolated, alone and withdrawn from society (through the process of imprisonment), and for some, they will become further isolated and withdrawn via the pains of their chronic illness.

There isn’t really a point to this blog: more like a rambling of frustrations towards all the children who will journey through our subpar reproductive healthcare system, who will navigate the stigma and assumptions littered within society. To all the women and people who menstruate who are currently wading through this sh*t show, educating themselves, their family, their friends and in some cases their GPs, those people unable to speak out, not knowing how or simply not wanting to. And to those in the Secure Estate, grappling with the pains of imprisonment and having their reproductive healthcare needs ignored, overlooked or missed.

I haven’t even mentioned menopause…

References:

Carlen, P. (1983) Women’s Imprisonment, Abingdon: Routledge.

Corston, Baroness J. (2007) The Corston Report: A Review on Women with Particular Vulnerabilities in the Criminal Justice System, London: Home office.

Endometriosis UK (2023) Endometriosis Facts and Figures [online] Available at: https://www.endometriosis-uk.org/endometriosis-facts-and-figures#:~:text=Endometriosis%20affects%201.5%20million%20women,of%20those%20affected%20by%20diabetes.&text=On%20average%20it%20takes%208,symptoms%20to%20get%20a%20diagnosis. [Accessed 24th August 2023]

Sykes, G. (1958/2007) The Society of Captives: A Study of a Maximum Security Prison, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Youth or Adult: can you tell?

This week’s blog begins with a game: youth or adult, secure estate in England and Wales. Below are some statements, and you simply need to guess (educated guesses please), whether the statement is about the youth, or adult secure estate. So, are the statements about children in custody (those under the age of 18 years old) or adults in custody (18+). When you’re ready…

- 70% decrease in custody in comparison to 10 years ago

- Segregation, A.K.A Solitary Confinement, used as a way of managing the most difficult individuals and those who pose a risk to themselves or others

- Racial disproportionality in relation to experiencing custody and being remanded to custody

- Self-harm is alarmingly high

- 1/3 have a known mental health disability

- Homelessness after release is a reality for a high proportion of individuals

- Over half of individuals released from custody reoffend, this number increases when looking at those sentenced to 6months of less

How many did you answer youth secure estate, and how many adult secure estate? Tally up! Did you find a 50/50 split? Did you find it difficult to answer? Should it be difficult to spot the differences between how children and adults are treated/experience custody?

All of the above relate specifically to children in custody. The House of Commons Committee (2021) have argued that the secure estate for children in England and Wales is STILL a violent, dangerous set of environments which do little to address the needs of children sentenced to custody or on remand. Across the academic literature, there is agreement that the youth estate houses some of the most vulnerable children within our society, yet very little is done to address these vulnerabilities. Ultimately we are failing children in custody! The Government said they would create Secure Schools as a custody option, where education and support would be the focus for the children sent here. These were supposed to be ready for 2020, and in all fairness, we have had a global pandemic to contend with, so the date was pushed to 2022: and yet where are they? Where is the press coverage on the positive impact a Secure School will make to the Youth estate? Does anyone really care? A number of Secure Training Centres (STCs) have closed down across the past 10 years, with an alarmingly high number of the institutions which house children in custody failing Ofsted inspections and HM Inspectorate of Prisons (2021) found violence and safety within these institutions STILL a major concern. Children experience bullying from staff, could not shower daily, experience physical restraint, 66% of children in custody experienced segregation which was an increase from the year prior (HM Inspectorate of Prisons, 2021). These experiences are not new, they are re-occurring, year-on-year, inspection after inspection: when will we learn?

The sad, angry, disgusting truth is you could have answered ‘adult secure estate’ to most of the statements above and still have been accurate. And this rings further alarm bells. In England and Wales, we are supposed to treat children as ‘children first, offenders second’. Yet if we look to the similarities between the youth and adult secure estate, what evidence is there that children are treated as children first? We treat all offenders the same, and we treat them appallingly. This is not a new argument, many have raised the same points and concerns for years, but we appear to be doing very little about it.

We are kidding ourselves if we think we have a separate system for dealing with children who commit crime, especially in relation to custody! It pains me to continue seeing, year on year, report after report, the same failings within the secure estate, and the same points made in relation to children being seen as children first in England and Wales: I just can’t see it in relation to custody- feel free to show me otherwise!

References:

House of Commons Committees (2021) Does the secure estate meet the needs of young people in custody? High levels of violence, use of force and self-harm suggest the youth secure estate is not fit for purpose [Online]. Available at: https://houseofcommons.shorthandstories.com/justice-youth-secure-estate/index.html. [Last accessed 4th April 2022].

HM Inspectorate of Prisons (2021) Children in Custody 2019-2020: An analysis of 12-18-year-old’s perceptions of their experiences in secure training centres and young offender institutions. London: Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons.

Merry Christmas

“Merry Christmas”, a seasonal greeting dating back in 1534 when Bishop John Fisher was the first on record to write it. Since then across the English-speaking world, Merry Christmas became the festive greeting to mark the winter festive season. Although it marks a single day, the greeting relates to an entire season from Christmas Eve to the 12th night (eve of the epiphany). The season simulates the process of leading to the birth, circumcision and the baptism of Jesus. Like all births, there is an essential joy in the process, which is why in the middle of it there is the calendar change of the year, to mark more clearly the need for renewal. At the darkest time of the year, for the Northern hemisphere the anticipation of life and lights to come soon. Baby Jesus becomes an image of piety immortalised in numerous mangers in cities around the world.

The meaning is primarily religious dating back to when faith was the main compass of moral judgment. In fact, the celebrations were the last remnants of the old religion before the Romans established Christianity as the main faith. The new religion brought some changes, but it retained the role of moral authority. What is right and wrong, fair and unfair, true and false, all these questions were identified by men of faith who guided people across life’s dilemmas. There is some simplicity in life that very difficult decisions can be referred to a superior authority, especially when people question their way of living and the social injustice they experience. A good, faithful person need not to worry about these things, as the greater the suffering in this life, the greater the happiness in the afterlife. Marx in his introduction to Hegel’s philosophy regarding religion said, “Die Religion ist das Opium des Volkes”, or religion is the opium of the people. His statement was taken out of context and massively misquoted when the main thrust of his point was how religion could absorb social discontent and provide some contentment.

Faith has a level of sternness and glumness as the requirement to maintain a righteous life is difficult. Life is limited by its own existence, and religion, in recognition of the sacrifices required, offers occasional moments for people to indulge and embrace a little bit of happiness. When religious doctrine forgot happiness, people became demoralised and rebellious. A lesson learned by those dour looking puritans who banned dancing and singing at their own peril! Ironically the need to maintain a virtuous life was reserved primarily for those who were oppressed, the enslaved, the poor, the women, many others deemed to have no hope in this life. The ones who lived a privileged life had to respond to a different set of lesser moral rules.

People, of course, know that they live in an unjust society regardless of the time; whether it is an absolute monarchy or a representative republic. Regardless of the regime, religion was there to offer people solace in despair and destitution with the hope of a better afterlife. Even in prisons the charitable wealthy will offer a few ounces of meat and grain for the prisoners to have at least a festive meal on Christmas Day. Traditionally, employers will offer a festive bonus so that employees can get a goose for the festive meal, leaving those who didn’t to be visited by the ghosts of their own greed, as Dickens tells us in a Christmas carol. At that point, Dickens concerned with dire working conditions and the oppression of the working classes subverts the message to a social one.

By the time we move to the age of discovery, we witness the way knowledge conflicts with faith and starts to question the existence of afterlife…but still we say Merry Christmas! There is a recognition that the message now is more humanist, social and even family focused rather than a reaffirmation of faith. So, the greeting may have remained the same, but it could symbolise something quite different. If that is the case, then our greeting today should mean, the need to embrace humanity to accept those around us unconditionally, work and live in the world fighting injustices around. “Merry Christmas” and Speak up to injustices. Rulers and managers come and go; their oppression, madness and tyranny are temporary but people’s convictions, collectivity and fortitude remain resolute.

Christmas is meant to be a happy time full of joy, wonder and gifts. Lights in the streets, cheerful music in the shops, a lot of good food and plenty of gifts. This is at least the “official” view; which has grown to become such an oppressive event for those who do not share this experience. There are people who this festive season live alone, and their social isolation will become even greater. There are those who live in abusive relationships. There are children who instead of gifts will receive abuse. There are people locked up feeling despair; traditionally in prisons suicide rates go rocket high at the festive season. There are those who live in such conditions that even a meal is a luxury that they cannot afford every day. There are who live without a shelter in cold and inhuman conditions. These are people to whom festivities come as a slap in the face, in some cases even literal, to underline the continuous unfairness of their situation.

Most of us may have read “the little match girl” as kids. A story that let us know of the complete desperation of those people living in poverty. A child, like the more than a million children every year that die hoping until the very end. The irony is that for many millions of people around the world conditions have not changed since the original publication of the story back in mid-19th century. During this Christmas, there will be a child in a hospital bed, a child with a family of refugees crossing at sea, or a child working in the most inhuman conditions. Millions of children whose only wish is not a gift but life. The unfairness of these conditions makes it clear that “Merry Christmas” is not enough of a greeting. So, either we need to rebrand the wish or change its meaning!

The Criminology Team would like to wish “Social Justice” for all; our colleagues who fight for the future, our students who hope for a better life, our community that wishes for a better tomorrow, our world who deals with the challenges of the environment and the pandemic. Diogenes the Cynic used to carry a lantern around in search of humans; we hope that this winter you have the opportunity (unlike Diogenes) to find another person and spend some pleasant moments together.