Home » Poverty (Page 6)

Category Archives: Poverty

Homelessness: Shedding an unfavourable light on a beautiful town!

Let me start by apologising for the tone of this blog and emphasis that what follows is rant based on my own opinion and not that of the university or co-authors of the blog. On 3 January I was incensed by a story in the Guardian outlining comments made by Simon Dudley, the Royal Borough of Windsor and Maidenhead’s Conservative leader, regarding homelessness and the impact (visually) that this could have on the forthcoming royal wedding. Mr Dudley commented that having homeless people on the streets at the time of the wedding would present “a beautiful town in a sadly unfavourable light” and that “Windsor is different and requires a more robust approach to begging” (Dudley, cited in Sherwood, 2018, online). Unfortunately, I am no longer shocked by such comments and have come to expect nothing less of Conservative leaders. I am however profoundly saddened that such a deep rooted social issue is brought back into the spot light, not because it reflects wider issues of inequality, disadvantage, poverty, or social exclusion that need addressing but because of a class based narrative driven by a royal wedding. Is Windsor really in need of special treatment? Is their experience of homelessness really worse than every other city in the UK? Or is simply that in an area with such wealth, and social connection, showing the world that we have a problem with homelessness is taking it a step too far. Whatever the reason, Shelter’s[1] (2017) tweet on the 29 December reminds us that homelessness is ‘…a crisis we are not handling as a country’.

As we approached the Christmas period it was estimated that children experiencing homelessness had reached a 10 year high with headlines like ‘Nearly 130,000 children to wake up homeless this Christmas’ (Bulman, 2017) marking our approach to the festive season. Similarly, Shelter warned of a Christmas homeless crisis and as the temperatures dropped emergency shelters were opened across London, contrary to the policy of only opening after three consecutive days of freezing temperatures (TBIF, 2017). Yet the significance of these headlines and the vast body of research into the homelessness crisis appears lost on Mr Dudley whose comments only add to an elitist narrative that if we can’t see it, it isn’t a problem. My issue is not with Mr Dudley’s suggestion that action is needed against aggressive begging and intimidation but with his choice of language. Firstly, to suggest that homelessness is a ‘sad’ thing is a significant understatement made worse by the fact that the focus of this sadness is not on homelessness itself but the fact that it undermines the tone of an affluent area. Secondly, the suggestion that the police should clear the homeless from the streets along with their ‘bags and detritus’ (Dudley, cited in Sherwood, 2018) is symbolic of much of the UK’s approach to difficult social issues; sticking a band aid on a fatal wound and hoping it works. Thirdly, and more deeply disturbing for me is the blame culture evident in his suggestion that homelessness is a choice that those begging in Windsor are ‘…not in fact homeless, and if they are homeless they are choosing to reject all support services…it is a voluntary choice’ (Dudley, cited in Sherwood, 2018). Homelessness is complex and often interlinked with other deeply rooted problems, therefore this blame attitude is not just short sighted but highly ignorant of the difficulties facing a growing proportion of the population.

Shelter. (2017) A safe, secure home is a fundamental right for everyone. It’s a crisis we are not handling as a country [Online]. Twitter. 29 December. Available from: https://twitter.com/shelter?lang=en [Accessed 4 January 2018].

Sherwood, H., (2018) Windsor council leader calls for removal of homeless before royal wedding. The Guardian [online]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2018/jan/03/windsor-council-calls-removal-homeless-people-before-royal-wedding [Accessed 04 January 2018].

The Big Issue Foundation. (2017) TBIF joins the Mayor of London’s Coalition to tackle rough sleeping [Online]. The Big Issue Website. Available from: https://www.bigissue.org.uk/news [Accessed 4 January 2018].

[1] a charity offering advice and support to those facing or experiencing homelessness

“A Christmas Carol” for the twenty-first century

The build up to Christmas appears more frenetic every year, but there comes a point where you call it a day. This hiatus between preparation and the festivities lends itself to contemplation; reflection on Christmases gone by and a review of the year (both good and bad). Some of this is introspective and personal, some familiar or local and some more philosophical and global.

Following from @manosdaskalou’ recent contemplation on “The True Message of Christmas”, I thought I might follow up his fine example and explore another, familiar, depiction of the festive period. While @manosdaskalou focused on wider European and global concerns, particularly the crisis faced by many thousands of refugees, my entry takes a more domestic view, one that perhaps would be recognised by Charles Dickens (1812- 1870) despite being dead for nearly 150 years.

One of the most distressing news stories this year was the horrific fire at Grenfell Tower where 71 people lost their lives. [1] Whilst Dickens, might not recognise the physicality of a tower block, the narratives which followed the disaster, would be all too familiar to him. His keen eye for social injustice and inequality is reflected in many of his books; A Christmas Carol certainly contains descriptions of gut wrenching, terrifying poverty, without which, Scrooge’s volte-face would have little impact.

In the immediacy of the Grenfell Tower disaster tragic updates about individuals and families believed missing or killed in the fire filled the news channels. Simultaneously, stories of bravery; such as the successful endeavours of Luca Branislav to rescue his neighbour and of course, the sheer professionalism and steadfast determination of the firefighters who battled extremely challenging conditions also began to emerge. Subsequently we read/watched examples of enormous resilience; for example, teenager Ines Alves who sat her GCSE’s in the immediate aftermath. In the aftermath, people clamoured to do whatever they could for survivors bringing food, clothes, toys and anything else that might help to restore some normality to individual life’s. Similarly, people came together for a variety of different celebrity and grassroots events such as Game4Grenfell, A Night of Comedy and West London Stand Tall designed to raise as much money as possible for survivors. All of these different narratives are to expected in the wake of a tragedy; the juxtaposition of tragedy, bravery and resilience help people to make sense of traumatic events.

Ultimately, what Grenfell showed us, was what we already knew, and had known for centuries. It threw a horrific spotlight on social injustice, inequality, poverty, not to mention a distinct lack of national interest In individual and collective human rights. Whilst Scrooge was “encouraged” to see the error of his ways, in the twenty-first century society appears to be increasingly resistant to such insight. While we are prepared to stand by and watch the growth in food banks, the increase in hunger, homelessness and poverty, the decline in children and adult physical and mental health with all that entails, we are far worse than Scrooge. After all, once confronted with reality, Scrooge did his best to make amends and to make things a little better. While the Grenfell Tower Inquiry might offer some insight in due course, the terms of reference are limited and previous experiences, such as Hillsborough demonstrate that such official investigations may obfuscate rather than address concerns. It would seem that rather than wait for official reports, with all their inherent problems, we, as a society we need to start thinking, and more, importantly addressing these fundamental problems and thus create a fairer, safer and more just future for everyone.

In the words of Scrooge:

“A merry Christmas to everybody! A happy New Year to all the world!” (Dickens, 1843/1915: 138)

[1] The final official figure of 71 includes a stillborn baby born just hours after his parents had escaped the fire.

Dickens, Charles, (1843/1915), A Christmas Carol, (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Co.)

The true message of Christmas

One of the seasonal discussions we have at social fora is how early the Christmas celebrations start in the streets, shops and the media. An image of snowy landscapes and joyful renditions of festive themes that appear sometime in October and intensify as the weeks unforld. It seems that every year the preparations for the festive season start a little bit earlier, making some of us to wonder why make this fuss? Employees in shops wearing festive antlers and jumpers add to the general merriment and fun usually “enforced” by insistent management whose only wish is to enhance our celebratory mood. Even in my classes some of the students decided to chip in the holiday fun wearing oversized festive jumpers (you know who you are!). In one of those classes I pointed out that this phenomenon panders to the commercialisation of festivals only to be called a “grinch” by one of the gobby ones. Of course all in good humour, I thought.

Nonetheless it was strange considering that we live in a consumerist society that the festive season is marred with the pressure to buy as much food as possible so much so, that those who cannot (according to a number of charities) feel embarrassed to go shopping; or the promotion of new toys, cosmetics and other trendy items that people have to have badly wrapped ready for the big day. The emphasis on consumption is not something that happened overnight. There have been years of making the special season into a family event of Olympic proportions. Personal and family budgets will dwindle in the need to buy parcels of goods, consume volumes of food and alcohol so that we can rejoice.

Many of us by the end of the festive season will look back with regret, for the pounds we put on, the pounds we spent and the things we wanted to do but deferred them until next Christmas. Which poses the question; What is the point of the holiday or even better, why celebrate Christmas anymore? Maybe a secular society needs to move away from religious festivities and instead concentrate on civic matters alone. Why does religion get to dictate the “season to be jolly” and not people’s own desire to be with the ones they want to be with? If there is a message within the religious symbolism this is not reflected in the shop-windows that promote a round-shaped old man in red, non-existent (pagan) creatures and polar animals.

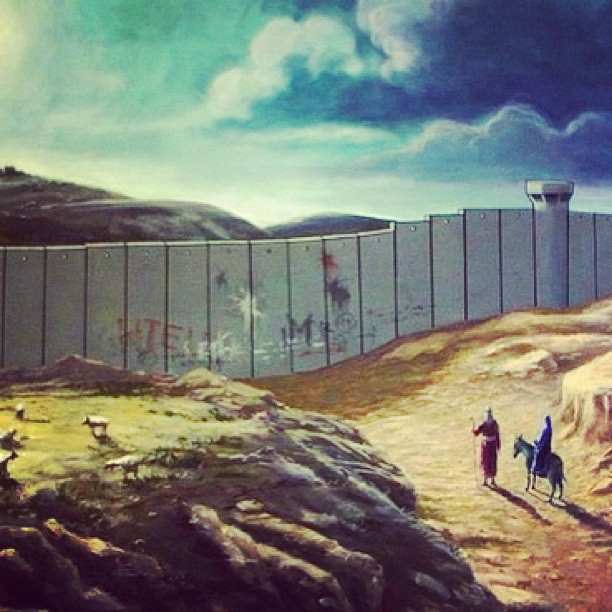

According to the religious message about 2000 years ago a refugee family gave birth to a child on their way to exile. The child would live for about 33 years but will change the face of modern religion. He promised to come back and millions of people still wait for his second coming but in the meantime millions of refugee children are piling up in detention centers and hundreds of others are dying in the journey of the damned. “A voice is heard in Ramah, mourning and great weeping, Rachel weeping for her children, because her children are no more” (Jeremiah 31:15). This is the true message of Christmas today.

Happy Holidays to our students and colleagues.

FYI: Ramah is a town in war torn Middle East

“Letters from America”: II

Having only visited Philadelphia once before (and even then it was strictly a visit to Eastern State Penitentiary with a quick “Philly sandwich” afterwards) the city is new to me. As with any new environment there is plenty to take in and absorb, made slightly more straightforward by the traditional grid layout so beloved of cities in the USA.

Particularly striking in Philadelphia are the many signs detailing the city’s history. These cover a wide range of topics; (for instance Mothers’ Day originates in the city, the creation of Walnut Street Gaol and commemoration of the great and the good) and allow visitors to get a feel for the city.

Unfortunately, these signs tell only part of the city’s story. Like many great historical cities Philadelphia shares horrific historical problems, that of poverty and homelessness. Wherever you look there are people lying in the street, suffering in a state of suspension somewhere between living and dying, in essence existing. The city is already feeling the chill winds of winter and there is far worse to come. Many of these people appear unable to even ask for help, whether because they have lost the will or because there are just too many knock backs. For an onlooker/bystander there is a profound sense of helplessness; is there anything I can do?, what should I do?, can I help or do I make things even worse?

The last time I physically observed this level of homelessness was in Liverpool but the situation appeared different. People were existing (as opposed to living) on the street but passers by acknowledged them, gave money, hot drinks, bottles of water and perhaps more importantly talked to them. Of course, we need to take care, drawing parallels and conclusions across time and place is always fraught with difficulty, particularly when relying on observation alone. But here it seems starkly different; two entirely different worlds – the destitute, homeless on the one hand and the busy Thanksgiving/Christmas shopper on the other. Worse still it seems despite their proximity ne’er the twain shall meet.

This horrible juxtaposition was brought into sharp focus last night when @manosdaskalou and I went out for an evening meal. We chose a beautiful Greek restaurant and thought we might treat ourselves for a change. We ordered a starter and a main each, forgetting momentarily, that we were in the land of super sized portions. When the food arrived there was easily enough for a family of 4 to (struggle to) eat. This provides a glaringly obvious demonstration of the dichotomy of (what can only really be described as) greed versus grinding poverty and deprivation, within the space of a few yards.

I don’t know what the answer is , but I find it hard to accept that in the twenty-first century society we appear to be giving up on trying seriously to solve these traumatic social problems. Until we can address these repetitive humanitarian crisis it is hard to view society as anything other than callous and cruel and that view is equally difficult to accept.