Home » Police (Page 8)

Category Archives: Police

Beyond education…

In a previous blog I wrote about the importance of going through HE as a life changing process. The hard skills of learning about a discipline and the issues, debates around it, is merely part of the fun. The soft skills of being a member of a community of people educated at tertiary level, in some cases, outweigh the others, especially for those who never in their lives expected to walk through the gates of HE. For many who do not have a history in higher education it is an incredibly difficult act, to move from differentiating between meritocracy to elitism, especially for those who have been disadvantaged all their lives; they find the academic community exclusive, arrogant, class-minded and most damning, not for them.

The history of higher education in the UK is very interesting and connected with social aspiration and mobility. Our University, along with dozens of others, is marked as a new institution that was created in a moment of realisation that universities should not be exclusive and for the few. In conversation with our students I mentioned how as a department and an institution we train the people who move the wheels of everyday life. The nurses in A&E, the teachers in primary education, the probation officers, the paramedics, the police officers and all those professionals who matter, because they facilitate social functioning. It is rather important that all our students understand that our mission statement will become their employment identity and their professional conduct will be reflective of our ability to move our society forward, engaging with difficult issues, challenging stereotypes and promoting an ethos of tolerance, so important in a society where violence is rising.

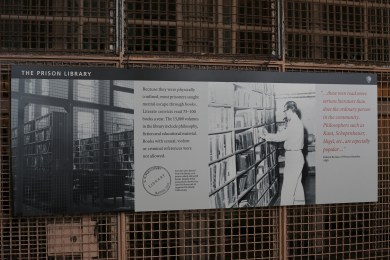

This week we had our second celebration of our prison taught module. For the last time the “class of 2019” got together and as I saw them, I was reminded of the very first session we had. In that session we explored if criminology is a science or an art. The discussion was long, and quite unexpected. In the first instance, the majority seem to agree that it is a social science, but somehow the more questions were asked, the more difficult it became to give an answer. What fascinates me in such a class, is the expectation that there is a clear fixed answer that should settle any debate. It is little by little that the realisation dawns; there are different answers and instead of worrying about information, we become concerned with knowledge. This is the long and sometimes rocky road of higher education.

Our cohort completed their studies demonstrating a level of dedication and interest for education that was inspiring. For half of them this is their first step into the world of HE whilst the other half are close to heading out of the University’s door. It is a great accomplishment for both groups but for the first who may feel they have a long way to go, I will offer the words of a greater teacher and an inspiring voice in my psyche, Cavafy’s ‘The First Step’

Even this first step

is a long way above the ordinary world.

To stand on this step

you must be in your own right

a member of the city of ideas.

And it is a hard, unusual thing

to be enrolled as a citizen of that city.

Its councils are full of Legislators

no charlatan can fool.

To have come this far is no small achievement:

what you have done already is a glorious thing

Thank you for entering this world. You earn it and from now on do not let others doubt you. You can do it if you want to. Education is there for those who desire it.

C.P. Cavafy, (1992) Collected Poems, Translated by Edmund Keeley and Philip Sherrard, Edited by George Savidis, Revised Edition, Princeton University Press, Princeton.

We Want Equality! When do we want it?

I’ve been thinking a lot about equality recently. It is a concept bandied around all the time and after all who wouldn’t want equal life opportunities, equal status, equal justice? Whether we’re talking about gender, race, sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status. religion, sex or maternity (all protected characteristics under the Equality Act, 2010) the focus is apparently on achieving equality. But equal to what? If we’re looking for equivalence, how as a society do we decide a baseline upon which we can measure equality? Furthermore, do we all really want equality, whatever that might turn out to be?

Arguably, the creation of the ‘Welfare State’ post-WWII is one of the most concerted attempts (in the UK, at least) to lay foundations for equality.[1] The ambition of Beveridge’s (1942) Report of the Inter-Departmental Committee on Social Insurance and Allied Services was radical and expansive. Here is a clear attempt to address, what Beveridge (1942) defined as the five “Giant Evils” in society; ‘squalor, ignorance, want, idleness, and disease’. These grand plans offer the prospect of levelling the playing field, if these aims could be achieved, there would be a clear step toward ensuring equality for all. Given Beveridge’s (1942) background in economics, the focus is on numerical calculations as to the value of a pension, the cost of NHS treatment and of course, how much members of society need to contribute to maintain this. Whilst this was (and remains, even by twenty-first century standards) a radical move, Beveridge (1942) never confronts the issue of equality explicitly. Instead, he identifies a baseline, the minimum required for a human to have a reasonable quality of life. Of course, arguments continue as to what that minimum might look like in the twenty-first century. Nonetheless, this ground-breaking work means that to some degree, we have what Beveridge (1942) perceived as care ‘from cradle to grave’.

Unfortunately, this discussion does not help with my original question; equal to what? In some instances, this appears easier to answer; for example, adults over the age of 18 have suffrage, the age of sexual consent for adults in the UK is 16. But what about women’s fight for equality, how do we measure this? Equal pay legislation has not resolved the issue, government policy indicates that women disproportionately bear the negative impact of austerity. Likewise, with race equality, whether you look at education, employment or the CJS there is a continuing disproportionate negative impact on minorities. When you consider intersectionality, many of these inequalities are heaped one on top of the other. Would equality be represented by everyone’s life chances being impacted in the same way, regardless of how detrimental we know these conditions are? Would equality mean that others have to lose their privilege, or would they give it up freely?

Unfortunately, despite extensive study, I am no closer to answering these questions. If you have any ideas, let me know.

References

Beveridge, William, (1942), Report of the Inter-Departmental Committee on Social Insurance and Allied Services, (HMSO: London)

The Equality Act, 2010, (London: TSO)

[1] Similar arguments could be made in relation to Roosevelt’s “New Deal” in the USA.

Goodbye 2018….Hello 2019

Now that the year is almost over, it’s time to reflect on what’s gone before; the personal, the academic, the national and the global. This year, much like every other, has had its peaks and its troughs. The move to a new campus has offered an opportunity to consider education and research in new ways. Certainly, it has promoted dialogue in academic endeavour and holds out the interesting prospect of cross pollination and interdisciplinarity.

On a personal level, 2018 finally saw the submission of my doctoral thesis. Entitled ‘The Anti-Thesis of Criminological Research: The case of the criminal ex-servicemen,’ I will have my chance to defend this work, so still plenty of work to do.

For the Criminology team, we have greeted a new member; Jessica Ritchie and congratulated the newly capped Dr Susie Atherton. Along the way there may have been plenty of challenges, but also many opportunities to embrace and advance individual and team work. In September 2018 we greeted a bumper crop of new apprentice criminologists and welcomed back many familiar faces. The year also saw Criminology’s 18th birthday and our first inaugural “Big Criminology Reunion”. The chance to catch up with graduates was fantastic and we look forward to making this a regular event. Likewise, the fabulous blog entries written by graduates under the banner of “Look who’s 18” reminded us all (if we ever had any doubt) of why we do what we do.

Nationally, we marked the centenaries of the end of WWI and the passing of legislation which allowed some women the right to vote. This included the unveiling of two Suffragette statues; Millicent Fawcett and Emmeline Pankhurst. The country also remembered the murder of Stephen Lawrence 25 years earlier and saw the first arrests in relation to the Hillsborough disaster, All of which offer an opportunity to reflect on the behaviour of the police, the media and the State in the debacles which followed. These events have shaped and continue to shape the world in which we live and momentarily offered a much-needed distraction from more contemporaneous news.

For the UK, 2018 saw the start of the Grenfell Tower Inquiry, the Windrush scandal, the continuing rise of the food bank, the closure of refuges, the iniquity of Universal Credit and an increase in homelessness, symptoms of the ideological programmes of “austerity” and maintaining a “hostile environment“. All this against a backdrop of the mystery (or should that be mayhem) of Brexit which continues to rumble on. It looks likely that the concept of institutional violence will continue to offer criminologists a theoretical lens to understand the twenty-first century (cf. Curtin and Litke, 1999, Cooper and Whyte, 2018).

Internationally, we have seen no let-up in global conflict, the situation in Afghanistan, Iraq, Myanmar, Syria, Yemen (to name but a few) remains fraught with violence. Concerns around the governments of many European countries, China, North Korea and USA heighten fears and the world seems an incredibly dangerous place. The awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to Denis Mukwege and Nadia Murad offers an antidote to such fears and recognises the powerful work that can be undertaken in the name of peace. Likewise the deaths of Professor Stephen Hawking and Harry Leslie Smith, both staunch advocates for the NHS, remind us that individuals can speak out, can make a difference.

To my friends, family, colleagues and students, I raise a glass to the end of 2018 and the beginning of 2019:

‘Let’s hope it’s a good one, without any fear’ (Lennon and Ono, 1974).

References:

Cooper, Vickie and Whyte, David, (2018), ‘Grenfell, Austerity and Institutional Violence,’ Sociological Research Online, 00, 0: 1-10

Curtin, Deane and Litke, Robert, (1999) (Eds), Institutional Violence, (Amsterdam: Rodopi)

Lennon, John and Ono, Yoko, (1974) Happy Xmas (War is Over), [CD], Recorded by John and Yoko: Plastic Ono Band in Shaved Fish. PCS 7173, [s.l.], Apple

Changes in Life

When I suggested writing for this blog to certain colleagues I was told that this topic would be of no interest and nobody would read it as it is not relevant. I consider the topic very relevant to me and to every woman. The term used is ‘women of a certain age’ (I hate the expression) to explain the menopause.

I am a 55-year-old woman who is going through the menopause and I make no apologies as there is nothing I can do about it. There is acceptance of women starting their periods and the advertisements for period poverty. There are extensive adverts, promotions, books all on pregnancy but very little about the menopause. At last, just this evening, I have seen an advert by Jenny Éclair on TV about a product for one symptom of the menopause. I fail to understand why this subject is not discussed more openly?

Having reached the menopause, I can honestly say this is the worst I have ever felt both emotionally and physically. The brain fog, not being able to put a sentence together sometimes, clumsiness, the lack of sleep, loss of confidence, weight gain; aching limbs. The list goes on. I know that each woman is different, and their body responds differently so I speak for me. I know that I am not alone though just by the conversations I have with other women and on the menopause chat room.

In accepting my situation and desperately trying to work through these symptoms I reflect on an incident where my mother was arrested for shoplifting. She would have been my age at the time. I was so angry at her as I was a serving police officer and I was so embarrassed. I never tried to understand why she did it. Did the menopause contribute to the theft of cushion covers she did not need? To this day we have never spoken about the incident and never will.

Also, my thoughts around this situation extends to the research I am conducting around the treatment of transgender people in prison. Researching the prison estate, I find that the prison population is getting older and the policies link to women in prison, catering for women and babies, addictions, mental health etc but there is no mention of older women going through the menopause?

I served in the police at a time when women were not equal to men and I would never have raised, and written this blog entry exposing ‘weaknesses’. To write this is progress for me and I can even see that the police are addressing the issues of the menopause through conversations, presentations and support groups. They have come a long way. All family, friends, colleagues and employers need to try and understand this debilitating change in life for us ‘women of a certain age’.

The Voice Behind the Music

Marginalised voices were the focal point of my dissertation.

My dissertation explored social issues through the musical genres of Rap and Hip-Hop. During the time period of writing my dissertation there was the rising debate surrounding the association of a new genre, Drill music, being linked to the rise in violent crimes by young people in England (London specifically). The following link to an article from the Guardian newspaper will provide a greater insight to the subject matter:

The idea of music having a direct correlation with criminality sweeps issues such as poverty, social deprivation, class and race all under the rug; when in reality these are just a few of the definitive issues that these marginalised groups face. We see prior examples of this in the late 80s, with rap group N.W.A with their song “F*** the police”. The song surrounded the topic of police brutality and brought light to the disgust and outrage of the wider community to this issue. Simultaneously to this, the N.W.A were refused from running concerts as they were accused of starting revolts. The song was made as a response to their environment, but why is freedom of speech limited to certain sectors of society?

In the present day, we see young people having lower prospects of being homeowners, high rates of unemployment, and the cost of living increasing. In essence the rich are getting richer and the poor continue to struggle; the violence of austerity at its finest. Grenfell Tower is the perfect example of this, for the sake of a cheaper cost lives were lost. Simply because these individuals were not in a position to greatly impact the design of their housing. Monetary status SHOULD NOT determine your right to life, but unfortunately in those circumstances it did.

The alienation of young people was also a topic that was highlighted within my research into my dissertation. In London specifically, youth clubs are being closed down and money is being directed heavily towards pensions. An idea would be to invest in young people as this would potentially provide an incentive and subsequently decrease the prospect of getting involved in negative activities.

In no means, was the aim to condone the violence but instead to simply shed light on the issues that young people face. There is a cry for help but the issue is only looked at from the surface as a musical problem. If only it were that simple, maybe considering the voice behind the music would lead to the solution of the problem.

Divided States of America

Nahida is a BA (Hons) Criminology graduate of 2017, who recently returned from travelling.

Ask anyone that has known me for a long time, they would tell you that I have wanted to go to America since I was a little girl. But, at the back of my mind, as a woman of colour, and as a Muslim, I feared how I would be treated there. Racial discrimination and persecution is not a contemporary problem facing the States. It is one that is rooted in the country’s history.

I had a preconceived idea, that I would be treated unfairly, but to be fair, there was no situation where I felt completely unsafe. Maybe that was because I travelled with a large group of white individuals. I had travelled the Southern states, including Louisiana, Texas, Tennessee and Virginia and saw certain elements that made me uncomfortable; but in no way did I face the harsh reality that is the treatment of people of colour in the States.

Los Angeles was my first destination. It was my first time on a plane without my family, so I was already anxious and nervous, but on top of that I was “randomly selected” for extra security checks. Although these checks are supposedly random and indiscriminate, it was no surprise to me that I was chosen. I was a Muslim after all; and Muslim’s are stereotyped as terrorists. I remember my travel companion, who was white, and did not have to undergo these checks, watch as I was taken to the side, as several other white travellers were able to continue without the checks. She told me she saw a clear divide and so could I.

In Lafayette, Louisiana, I walked passed a man in a sandwich café, who fully gawked at me like I had three heads. As I had walked to the café, I noticed several cars with Donald Trump stickers, which had already made me feel quite nervous because several of his supporters are notorious for their racist views.

Beale Street in Downtown Memphis is significant in the history of the blues, so it is a major tourist attraction for those who visit. It comes alive at night; but it was an experience that I realised how society has brainwashed us into subliminal racism. The group of people I was travelling with were all white and they had felt uncomfortable and feared for their safety the entire time we were on Beale Street. The street was occupied by people of colour, which was not surprising considering Memphis’ history with African-Americans and the civil rights movement. That night, the group decided to leave early for the first time during the whole trip. I asked, “Do you think it’s our subconscious racist views, which explains why we feel so unsafe?” It was a resounding yes. As a woman of colour, I was not angry at them, because I knew they were not racist, but a fraction of their mind held society’s view on people of colour; the view that people of colour are criminals, and, or should be feared. That viewpoint was clearly exhibited by the heavy police presence throughout the street. It was the most heavily policed street I had seen the entire time I was in the States. Even Las Vegas’ strip didn’t seem to have that many police officers patrolling.

It was on the outskirts of Tennessee, where I came across an individual whose ignorance truly blindsided me. We had pulled up at a gas station, and the man approached my friends. I was inside the station at this point. The man was preaching the bible and looking for new followers for his Church. He stumbled upon the group and looked fairly displeased with the way they were dressed in shorts and skirts. He struck a conversation with them and asked generic questions like “Where are you from?” etcetera. When he found out the group were from England, he asked if in England, they spoke English. At this point, the group concluded that he wasn’t particularly educated. I joined the group outside, post this conversation, and the man took one look at me and turned to my friend who was next to him, and shouted “Is she from India?” The way he yelled seemed like an attempt to guage if I could understand him or not. Not only was that rude, but also very ignorant, because he made a narrow-minded assumption that a person of my skin colour, could not speak English, and were all from India.

I was completely taken aback, but also, I found the situation kind of funny. I have never met someone so uneducated in my entire life. In England, I have been quite privileged to have never faced any verbal or physical form of racial discrimination; so, to meet this man was quite interesting. This incident took place in an area populated by white individuals. I was probably one of the very few, or perhaps the first Asian woman he had ever met in his life; so, I couldn’t make myself despise him. He was not educated, and to me, education is the key to eliminating racism.

Also, the man looked be in his sixties, so his views were probably set, so anything that any one of us could have said in that moment, would never have been able to erase the years of discriminatory views he had. The bigotry of the elder generation is a difficult fight because during their younger days, such views were the norm; so, changing such an outlook would take a momentous feat. It is the younger generation, that are the future. To reduce and eradicate racism, the younger generation need to be educated better. They need to be educated to love, and not hate and fear people that have a different skin colour to them.

A help or a hindrance: The Crime Survey of England and Wales

I recently took part in the Crime Survey for England and Wales and, in the absence of something more interesting to talk about, I thought I would share with you how exchanging my interviewer hat for an interviewee one gave me cause to consider the potential impact that I could have on the data and the validity of the data itself. My reflections start with the ‘incentive’ used to encourage participation, which took the shape of a book of 6 first class stamps accompanying the initial selection letter. This is not uncommon and on the surface, is a fair way of encouraging or saying thank you to participants. Let’s face it, who doesn’t like a freebie especially a useful one such as stamps which are now stupidly expensive. The problem comes when you consider the implications of the gesture and the extent to which this really is a ‘freebie’, for instance in accepting the stamps was I then morally obliged to participate? There was nothing in the letter to suggest that if you didn’t want to take part you needed to return the stamps, so in theory at least I was under no obligation to participate when the researcher knocked on the door but in practice refusing to take part while accepting the stamps, would have made me feel uncomfortable. While the question of whether a book of first class stamps costing £3.90 (Royal Mail, 2018) truly equates to 50 minutes of my time is a moot point, the practice of offering incentives to participate in research raises a moral and/or ethical question of whether or not participation remains uncoerced and voluntary.

My next reflection is slightly more complex because it relates to the interconnected issues associated with the nature and construction of the questions themselves. Take for example the multitude of questions relating to sexual offending and the way in which similar questions are asked with the alteration of just one or two words such as ‘in the last 12 months’ or ‘in your lifetime’. If you were to not read the questions carefully, or felt uncomfortable answering such questions in the presence of a stranger and thus rushed them, you could easily provide an inaccurate answer. Furthermore, asking individuals if they have ‘ever’ experiences sexual offending (all types) raises questions for me as a researcher regarding the socially constructed nature of the topic. While the law around sexual offending is black and white and thus you either have or haven’t experienced what is defined by law as a sexual offence, such questions fail to acknowledge the social aspect of this offence and the way in which our own understanding, or acceptance of certain behaviours has changed over time. For instance, as an 18 year old I may not have considered certain behaviours within a club environment to be sexual assault in the same way that I might do now. With maturity, education and life experience our perception of behaviour changes as do our acceptance levels of them. In a similar vein, society’s perception of such actions has changed over time, shifting from something that ‘just happens’ to something that is unacceptable and inappropriate. I’m not saying that the action itself was right back then and is now wrong, but that quantitative data collected hold little value without a greater understanding of the narrative surrounding it. Such questions are only ever going to demonstrate (quantitatively) that sexual offending is problematic, increasing, and widely experienced. If we are honest, we have always known this, so the publication of quantitative figures does little to further our understanding of the problem beyond being able to say ‘x number of people have experienced sexual offending in their lifetime’. Furthermore, the clumping together of all, or certain sexual offences muddies the water further and fails to acknowledge the varying degree of severity and impact of offences on individuals and groups within society.

Interconnected with this issue of question relevance, is the issue of question construction. A number of questions ask you to reflect upon issues in your ‘local area’, with local being defined as being within a 10-15 minute walk of your home, which for me raised some challenges. Firstly, as I live in a village it was relatively easy for me to know where I could walk to in 10/15 minutes and thus the boundary associated with my responses but could the same be said for someone who 1) doesn’t walk anywhere or 2) lives in an urban environment? This issue is made more complex when it comes to knowing what crimes are happening in the ‘local’ area, firstly because not everyone is an active community member (as I am) therefore making any response speculative unless they have themselves been a victim of crime – which is not what these questions are asking. Secondly, most people spend a considerable amount of time away from home because of work, so can we really provide useful information on crime happening in an area that we spend little time in? In short, while the number of responses to these questions may alleviate some of these issues the credibility, and in turn usefulness of this data is questionable.

I encountered similar problems when asked about the presence and effectiveness of the local police. While I occasionally see a PCSO I have no real experience or accurate knowledge of their ‘local’ efficiency or effectiveness, not because they are not doing a good job but because I work away from home during the day, austerity measures impact on police performance and thus police visibility, and I have no reason to be actively aware of them. Once again, these questions will rely on speculative responses or those based on experiences of victimisation which is not what the question is actually asking. All in all, it is highly unlikely that the police will come out favourable to such questions because they are not constructed to elicit a positive response and give no room for explanation of your answer.

In starting this discussion, I realise that there is so much more I could say, but as I’ve already exceeded my word limit I’ll leave it here and conclude by commenting that although I was initially pleased to be part of something that we as Criminologist use in our working lives, I was left questioning its true purpose and whether my knowledge of the field actually allowed me to be an impartial participant.