Home » NHS

Category Archives: NHS

Will Keir Starmer’s plans to abolish NHS England, help to save the NHS?

In a land-mark event, British Prime Minister Keir Starmer has unveiled plans to abolish NHS England, to bring the NHS back into government control. Starmer justifies much of this change with streamlining operations and enhancing efficiency within the NHS, that in recent years has faced a backlash following long queues and an over-stretched staff pool. Moreover, this is part of Starmer’s plan to limit the power of control from bureaucratic systems.

NHS England was established in 2013 and has taken control and responsibility of the NHS’s daily operational priorities. Primarily, NHS England is invested in allocating regional funds to local health care systems and ensuring the smooth delivery of health care across the NHS. However, concerns, particularly in Parliament have been raised in relation to the merging of NHS England and the Department’s of Health and Social care that is alleged by critics to have brought inefficient services and an increase of administrative costs.

Considering this background, the plans to abolish NHS England, for Starmer come under two core priorities. The first is enhancing democratic accountability. This is to ensure that the expenditures of the NHS are contained within government control, thus it is alleged that this will improve efficiency and suitable allocation of spending. The second is to reduce the number of redundancies. This is backed by the idea that by streamlining essential services will allow for more money to be allocated to fund new Doctors and Nurses, who of course work on the front line.

This plan by Starmer has been met with mixed reviews. As some may say that it is necessary to bring the NHS under government control, to eliminate the risks of inefficient services. However, some may also question if taking the NHS under government control may necessarily result in stability and harmony. What must remain true to the core of this change is the high-quality delivery of health care to patients of the NHS. The answer to the effectiveness of this policy will ostensibly be made visible in due course. As readers in criminology, this policy change should be of interest to all of us… This policy will shape much of our public access to healthcare, thus contributing to ideas on health inequalities. From a social harm perspective, this policy is of interest, as we witness how modes of power and control play a huge role in instrumentally shaping people’s lives.

I am interested to hear any views on this proposal- feel free to email me and we can discuss more!

Birth Trauma

I recently passed through Rugby Motorway Services with my family and I was amazed by what was on offer. It consisted of a free internal and external play area and the most baby friendly changing rooms that I have ever encountered. This visit to the Rugby services made me think;

Isn’t it a shame that the same amount of family friendly consideration is not found elsewhere.

Even more so;

Isn’t it a shame that many babies, mothers and birthing parents are treated with such a common and serious violence during the birth

The Birth Trauma Inquiry has been published this week, I am sure that CRI3003 students would be able to critique this Inquiry but in terms of the responses from mothers who have experienced birth trauma it makes for an incredibly harrowing read.

In the words of one mother;

‘Animals were treated better than the way we were treated in hospital’ (p.26).

Yet, none of these accounts of violence are surprising; casual conversations with friends, family, relatives resemble many of the key themes highlighted within the inquiry. The inquiry includes accounts of mothers before, during and after birth being ‘humiliated’ (p.20) and bullied, experiencing extreme amounts of pain, financial ruin, life limiting physical and mental health problems, due to institutional issues raised such as: negligence, poor professional practice, mistakes, mix ups, lack of consent, inhumane treatment, lack of pain relief and compassion. With the most serious consequences being baby and or mother loss.

The report also makes reference to at least a couple of incidents involving mobile phone usage. This did remind me of a conversation that I was having with a fellow criminologist quite recently. Aside from issues that have existed for a long time, it seems that the use of phones may impact on our ability to work in a safe and compassionate manner. I am sure that some staff scroll on phones when victims of crime report to the police station, or scroll whilst ‘caring’ for someone who is either mentally or physically unwell. How such small technological devices seem to have such huge impact on human interaction amazes me.

A quote from the inquiry states: ‘the baby is the candy, the mum is the wrapper, and once the baby is out of the wrapper, we cast it aside’ (p.20), how awful is that?

All-Party Parliamentary Group. Listen to Mums: Ending the Postcode Lottery on Perinatal Care (2024). Available at: https://www.theo-clarke.org.uk/sites/www.theo-clarke.org.uk/files/2024-05/Birth%20Trauma%20Inquiry%20Report%20for%20Publication_May13_2024.pdf [Accessed 16/05/24].

When This is Over: Reflections on an Unequal Pandemic

This week a book was released which I both co-edited and contributed to and which has been two years in the making. When This is Over: Reflections on an Unequal Pandemic is a volume combining a range of accounts from artists to poets, practitioners to academics. Our initial aim of the book was borne out of a need for commemoration but we cannot begin to address this without considering inequalities throughout the pandemic.

Each of the four editors had both personal and professional reasons for starting the project. I – like many – was (and still is) deeply affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. When we first went into lockdown, we were shown the data every day, telling us the numbers of people who had the virus and of those who had died with COVID-19. Behind these numbers, I saw each and every person. I thought about their loved ones left behind, how many of them died alone without being able to say goodbye other than through a video screen. I thought about what happened to the bodies afterwards, how death rites would be impacted and how the bereaved would cope without hugs and face to face social support. Then my grandmother died. She had overcome COVID-19 in the way that she was testing negative. But I heard her lungs on the day she died. I know. And so, I became even more consumed with questions of the COVID-19 dead, with/of debates. I was angry at the narratives surrounding the disposability of people’s lives, at people telling me ‘she had a good innings’. It was personal now.

I now understood the impact of not being able to hug my grandpa at my grandmother’s funeral, and how ‘normal’ cultural practices surrounding death were disturbed. My grandmother loved singing in choirs and one of the traumatic parts of our bereavement was not being able to sing at her funeral as she would have wanted and how we wanted to remember her. Lucy Easthope, a disaster planner and one of my co-authors speaks of her frustrations in this regard:

“we’ve done something incredibly traumatising to the families that is potentially bigger than the bereavement itself. In any disaster you should still allow people to see the dead. It is a gross inhumanity of bad planning that people couldn’t’t visit the sick, view the deceased’s bodies, or attend funerals. Had we had a more liberal PPE stockpile we could have done this. PPE is about accessing your loved ones and dead ones, it is not just about medical professionals.”

The book is divided into five parts, each addressing a different theme all of which I argue are relevant to criminologists and each part including personal, professional, and artistic reflections of the themes. Part 1 considered racialised, classed, and gendered identities which impacted on inequality throughout the pandemic, asking if we really are in this together? In this section former children’s laureate Michael Rosen draws from his experience of having COVID-19 and being hospitalised in intensive care for 48 days. He writes about disposability and eugenics-style narratives of herd immunity, highlighting the contrast between such discourse and the way he was treated in the NHS: with great care and like any other patient.

The second part of the book considers how already existing inequalities have been intensified throughout the pandemic in policing, law and immigration. Our very own @paulsquaredd contributed a chapter on the policing of protests during the pandemic, drawing on race in the Black Lives Matter protests and gender in relation to Sarah Everard. As my colleagues and students might expect, I wrote about the treatment of asylum seekers during the initial lockdown periods with a focus on the shift from secure and safe self-contained housing to accommodating people seeking safety in hotels.

Part three considers what happens to the dead in a pandemic and draws heavily on the experiences of crematoria and funerary workers and how they cared for the dead in such difficult circumstances. This part of the book sheds light on some of the forgotten essential workers during the pandemic. During lockdown, we clapped for NHS workers, empathised with supermarket workers and applauded other visible workers but there were many less visible people doing valuable unseen work such as caring for the dead. When it comes to death society often thinks of those who cared for them when they were alive and the bereaved who were left to the exclusion of those who look after the body. The section provides some insight into these experiences.

Moving through the journey of life and death in a pandemic, the fourth section focusses on questions of commemoration, a process which is both personal and political. At the heart of commemorating the COVID-19 dead in the UK is the National COVID Memorial Wall, situated facing parliament and sat below St Thomas’ hospital. In a poignant and political physical space, the unofficial wall cared for by bereaved family members such as Fran Hall recognises and remembers the COVID dead. If you haven’t visited the wall yet, there will be a candlelit vigil walk next Wednesday, 29th March at 7pm and those readers who live further afield can digitally walk the wall here, listening to the stories of bereaved family members as you navigate the 150,837 painted hearts.

The final part of the book both reflects on the mistakes made and looks forward to what comes next. Can we do better in the next pandemic? Emergency planner Matt Hogan presents a critical view on the handling of the pandemic, returning to the refrain, ‘emergency planning is dead. Long live emergency planning’. Lucy Easthope is equally critical, developing what she has discussed in her book When the Dust Settles to consider how and what lessons we can learn from the management of the pandemic. Lucy calls out for activism, concluding with calls to ‘Give them hell’ and ‘to shout a little louder’.

Concluding in his afterword, Gary Younge suggests this is ‘teachable moment’, but will we learn?

When This is Over: Reflections on an Unequal Pandemic is published by Policy Press, an imprint of Bristol University Press. The book can be purchased directly from the publisher who offer a 25% discount when subscribing. It can also be purchased from all good book shops and Amazon.

A race to the bottom

Happy new year to one and all, although I suspect for many it will be a new year of trepidation rather than hope and excitement.

It seems that every way we turn there is a strike or a threat of a strike in this country, reminiscent, according to the media, of the 1970s. It also seems that every public service we think about (I mean this in the wider context so would include Royal Mail for example,) is failing in one way or another. The one thing that strikes me though, pardon the pun, is that none of this has suddenly happened. And yet, if you were to believe media reporting, this is something that is caused by those pesky unions and intransigent workers or is it the other way round? Anyway, the constant rhetoric of there is ‘no money’, if said often enough by politicians and echoed by media pundits becomes the lingua franca. Watch the news and you will see those ordinary members of the public saying the same thing. They may prefix this with ‘I understand why they are striking’ and then add…’but there is no money’.

When I listen to the radio or watch the news on television (a bit outdated I know), I am incensed by questions aimed at representatives of the railway unions or the nurses’ union, amongst others, along the lines of ‘what have you got to say to those businesses that are losing money as a result of your strikes or what would you like to say to patients that have yet again had their operations cancelled’? This is usually coupled with an interview of a suffering business owner or potential patient. I know what I would like to say to the ignorant idiot that asked the question and I’m sure most of you, especially those that know me, know what that is. Ignorant, because they have ignored the core and complex issues, wittingly or unwittingly, and an idiot because you already know the answer to the question but also know the power of the media. Unbiased, my ….

When we look at all the different services, we see that there is one thing in common, a continuous, often political ideologically uncompromising drive to reduce real time funding for public services. As much as politicians will argue about the amount of money ploughed into the services, they know that the funding has been woefully inadequate over the years. I don’t blame the current government for this, it is a succession of governments and I’m afraid Labour laying the blame at the Tory governments’ door just won’t wash. Social care, for example, has been constantly ignored or prevaricated over, long before the current Tories came to power, and the inability of social care to respond to current needs has a significant knock-on effect to health care. I do however think the present government is intransigent in failing to address the issues that have caused the strikes. Let us be clear though, this is not just about pay as many in government and the media would have you believe. I’m sure, if it was, many would, as one rather despicable individual interviewed on the radio stated, ‘suck it up and get on with it’. I have to add, I nearly crashed the car when I heard that, and the air turned blue. Another ignoramus I’m afraid.

Speak to most workers and they will tell you it is more about conditions rather than pay per se. Unfortunately, those increasingly unbearable and unworkable conditions have been caused by a lack of funding, budget restraints and pay restraints. We now have a situation where people don’t want to work in such conditions and are voting with their feet, exacerbating the conditions. People don’t want to join those services because of poor pay coupled with unworkable conditions. The government’s answer, well to the nurses anyway, is that they are abiding by the independent pay review body. That’s like putting two fingers up to the nurses, the health service and the public. When I was in policing it had an independent pay review body, the government didn’t always abide by it, notably, they sometimes opted to award less than was recommended. The word recommendation only seems to work in favour of government. Now look at the police service, underfunded, in chaos and failing to meet the increasing demands. Some of those demands caused by an underfunded social and health care service, particularly mental health care.

Over the years it has become clear that successive governments’ policies of waste, wasted opportunity, poor decision making, vote chasing, and corruption have led us to where we are now. The difference between first and third world country governments seems to only be a matter of degree of ineptitude. It has been a race to the bottom, a race to provide cheap, inadequate services to those that can’t afford any better and a race to suck everyone other than the rich into the abyss.

A government minister was quoted as saying that by paying wage increases it would cost the average household a thousand pound a year. I’d pay an extra thousand pound, in fact I’d pay two if it would allow me to see my doctor in a timely manner, if it gave me confidence that the ambulance would turn up promptly when needed, if it meant a trip to A&E wouldn’t involve a whole day’s wait or being turned away or if I could get to see a dentist rather than having to attempt DIY dentistry in desperation. I’d like to think the police would turn up promptly when needed and that my post and parcels would be delivered on time by someone that had the time to say hello rather than rushing off because they are on an unforgiving clock (particularly pertinent for elderly and vulnerable people).

And I’m not poor but like so many people I look at the new year with trepidation. I don’t blame the strikers; they just want to improve their conditions and vis a vis our conditions. Blaming them is like blaming cows for global warming, its nonsensical.

And as a footnote, I wonder why we never hear about our ex-prime minister Liz Truss and her erstwhile Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng; what a fine mess they caused. But yesterday’s news is no news and yet it is yesterday’s news that got us to where we are now. Maybe the media could report on that, although I suspect they probably won’t.

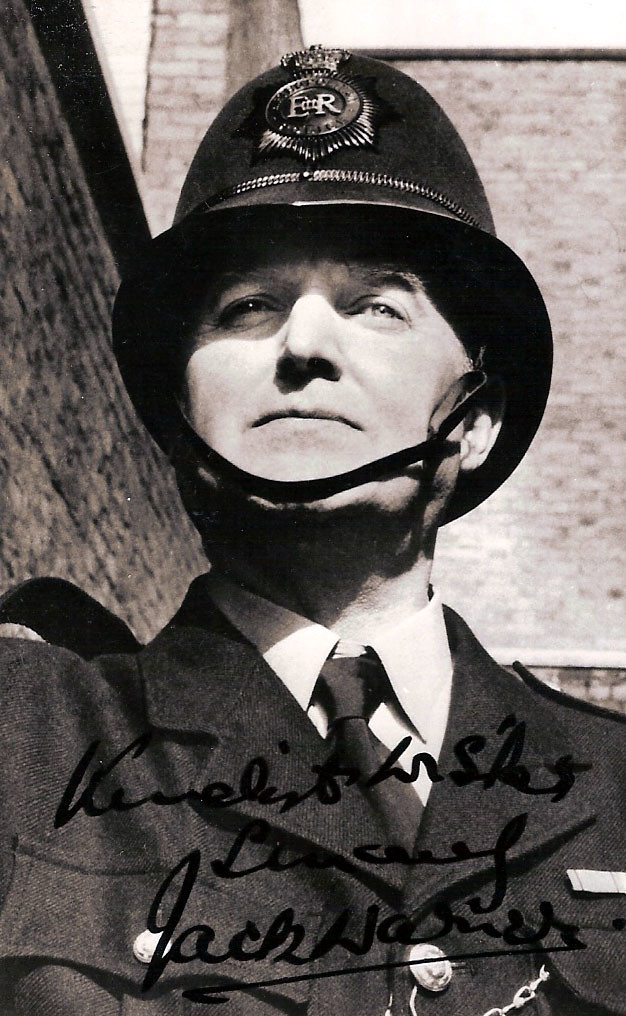

“Quelle surprise” – another fine mess

The recent HMICFRS publication An inspection of vetting misconduct and misogyny in the police service makes difficult reading for those of us that have or have had any involvement in the police service in England and Wales. Of course, this is not the first such report and I dare say it will not be the last. There is enough evidence both academic and during the course of numerous inquiries to suggest that there is institutional corruption of all sorts in the police service, coupled with prevailing racist and misogynistic attitudes. Hardly a surprise then that public confidence is at an all-time low.

As with so many reports and associated inquiries, the finger of blame is pointed at the institution or individuals within it. The failings are organisational failings or departmental or individual. I cast my mind back to those inquiries into the failings of social services or the failings of NHS trusts or the failings of the Fire and Rescue service or any other public body, all the fault of the organisation itself or individuals within it. Too many inquiries and too many failings to count. More often than not the recommendations from these reports and inquiries involve rectifying processes and procedures and increasing training. Rarely if ever do these reports even dare to dip their toe into the murky waters relating to funding. Nobody on these inquiries would have the audacity to suggest that the funding decisions made in the dark corridors of government would later have a significant contribution to the failings of all of these organisations and the individuals within them. Perhaps that’s why those people are chosen to head the inquiries or maybe the funding decisions are long forgotten.

Twenty percent budget cuts in public services in 2010/11 meant that priorities were altered often with catastrophic consequences. But to be honest the problems go much further back than the austerity measures of 2010/11. Successive governments have squeezed public services in the interest of efficiency and effectiveness. The result, neither being achieved, just some tinder box ready to explode into disaster. And yet more hand wringing and finger pointing and costly inquiries.

The problem is not just that the organisations failed or that departments or individuals failed, the problem is that all the failings might have been prevented if there was money available to deliver the service properly in the first place. And to do that, there needs to be enough staff, enough training, and enough equipment. And who is responsible for ensuring that happens?

Now you may say that is all very well but what of the police officers that are racist and misogynistic or corrupt and what of institutional corruption? After all the HMICFRS report is not just about vetting procedures but about the attitudes and behaviours of staff. A good point but let me point you to the behaviour of government, not just this government but preceding governments as well. The expenses scandal, the bullying allegations, the improper behaviour in parliament, the complete disregard for the ethics or for that matter, common decency. And what of those successive budget cuts and lack of willingness to address very real issues faced by staff in the organisations.

Let me also point you to the behaviour of the general public from whom the police officers are recruited. A society where parents that attend children’s football matches and hurl abuse at the referee and linesmen, even threatening to see them in the car park after the match. Not a one off but from recent reports a weekly occurrence and worse. A society now where staff in shops are advised not to challenge shoplifters in fear of their own safety. A society where there is a complete disregard for the law by many on a daily basis, including those that consider themselves law abiding citizens. A society where individuals blame everyone else, always in need of some scapegoat somewhere. A society where individuals know individually and collectively how they want others to behave but don’t know or disregard how they should behave.

I’m not surprised by the recent reports into policing and other services, saddened but not surprised. I’m not naïve enough to think that society was really any better at some distant time in the past, in fact there were some periods where it was definitely worse and policing of any sort has always been problematic. My fear is we are heading back to the worst times in humanity and these reports far from highlighting just an organisational problem are shining a floodlight on a societal one. But it suits everyone to confine the focus to the failings of organisations and the individuals within them. Not my fault, not my responsibility it’s the others not me, quelle surprise.

‘Now is the winter of our discontent’

As I write this blog, we await the detail of what on earth government are going to do to prevent millions of our nations’ populations plummeting headlong into poverty. It is our nations in the plural because as it stands, we are a union of nations under the banner Great Britain; except that it doesn’t feel that great, does it?

As autumn begins and we move into winter we are seeing momentum gaining for mass strikes across various sectors somewhat reminiscent of the ‘winter of discontent’ in 1979. A few of us are old enough to remember the seventies with electricity blackouts and constant strikes and soaring inflation. Enter Margaret Thatcher with a landslide election victory in 1979. People had had enough of strikes, believing the rhetoric that the unions had brought the downfall of the nation. Few could have foreseen the misery and social discord the Thatcher government and subsequent governments were about to sow. Those governments sought to ensure that the unions would never be strong again, to ensure that working class people couldn’t rise up against their business masters and demand better working conditions and better pay. And so, in some bizarre ironic twist, we have a new prime minister who styles herself on Thatcher just as we enter a period of huge inflationary pressures on families many of whom are already on the breadline. It is no surprise that workers are voting to go on strike across a significant number of sectors, the wages just don’t pay the bills. Perhaps most surprising is the strike by barristers, those we wouldn’t consider working class. Jock Young was right, the middle classes are staring into the abyss. Not only that but their fears are now rapidly being realised.

I listened to a young Conservative member on the radio the other day extolling the virtues of Liz Truss and agreeing with the view that tax cuts were the way forward. Trickle down economics will make us all better off. It seems though that no matter what government is in power, I have yet to see very much trickle down to the poorer sectors of society or for that matter, anyone. The blame for the current economic state and the forthcoming recession it seems rests fairly on the shoulders of Vladimir Putin. Now I have no doubt that the invasion of Ukraine has unbalanced the world economic order but let’s be honest here, social care, the NHS, housing, and the criminal justice system, to name but a few, were all failing and in crisis long before any Russian set foot in the Ukraine.

That young Conservative also spoke about liberal values, the need for government to step back and to interfere in peoples lives as little as possible. Well previous governments have certainly done that. They’ve created or at least allowed for the creation of the mess we are now in by supporting, through act or omission, unscrupulous businesses to take advantage of people through scurrilous working practices and inadequate wages whilst lining the pockets of the wealthy. Except of course government have been quick to threaten action when people attempt to stand up for their rights through strike action. Maybe being a libertarian allows you to pick and choose which values you favour at any given time, a bit of this and a bit of that. It’s a bit like this country’s adherence to ideals around human rights.

I wondered as I started writing this whether we were heading back to a winter of discontent. I fear that in reality that this is not a seasonal thing, it is a constant. Our nations have been bedevilled with inadequate government that have lacked the wherewithal to see what has been developing before their very eyes. Either that or they were too busy feathering their own nests in the cesspit they call politics. Either way government has failed us, and I don’t think the new incumbent, judging on her past record, is likely to do anything different. I suppose there is a light at the end of the tunnel, we have pork markets somewhere or other.

They think it’s all over…….

Probably the most famous quote in the history of English football was that made by Kenneth Wolstenholme at the end of the 1966 World Cup final where he stated as Geoff Hurst broke clear of the West German defence to score the 4th goal that “Some people are on the pitch…. they think it’s all over…….it is now”. I have been reminded of this quote as we reach April 1st, 2022 when all Coronavirus restrictions in England essentially come to an end. We are moving from a period of pandemic restrictions to one of “living with Covid”. Whilst the prevailing narrative has focussed on “it’s over” the national data sets would suggest it is most definitely not. We are currently experiencing another wave of infections driven by the Omicron BA-2 variant. Cases of Covid infection have been rising steadily over the past couple of weeks and we are now seeing hospital admissions and deaths rise too. This has led to an interesting tension between current politically driven and public health driven advice.

The overriding question then is why remove all restrictions now if infection rates are so high. The answer sits with science and the success of the vaccination programme, and the protection it affords, which to date has seen 86% of the eligible population have two jabs and 68% boosted with a third. Furthermore, we are now at the start of the Spring booster programme for the over 75s and the most vulnerable. The introduction of the vaccine has seen a dramatic fall in serious illness associated with infection and the UK government now believe that this is a virus we can live with and we should get on with our lives in a sensible and cautious way without the need for mandated restrictions. The advances gained in both the vaccination programme, anti-viral therapies and treatments have been enormous and underpin completely the current and future situation. So, the narrative shifts to one that emphasises learning to live with the virus and to that end the Government has provided us with guidance. The UK Government’s “Living with Covid Plan” COVID-19 Response – Living with COVID-19.docx (publishing.service.gov.uk) has four key principles at its heart:

- Removing domestic restrictions while encouraging safer behaviours through public health advice, in common with longstanding ways of managing most other respiratory illnesses;

- Protecting people most vulnerable to COVID-19: vaccination guided by Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI) advice, and deploying targeted testing;

- Maintaining resilience: ongoing surveillance, contingency planning and the ability to reintroduce key capabilities such as mass vaccination and testing in an emergency; and

- Securing innovations and opportunities from the COVID-19 response, including investment in life sciences.

So, in addition to the restrictions already removed from 1 April, the Government will:

- Remove the current guidance on voluntary COVID-status certification in domestic settings and no longer recommend that certain venues use the NHS COVID Pass.

- Update guidance setting out the ongoing steps that people with COVID-19 should take to minimise contact with other people. This will align with the changes to testing.

- No longer provide free universal symptomatic and asymptomatic testing for the general public in England.

- Consolidate guidance to the public and businesses, in line with public health advice.

- Remove the health and safety requirement for every employer to explicitly consider COVID-19 in their risk assessments.

- Replace the existing set of ‘Working Safely’ guidance with new public health guidance

My major concern with these changes is the massive scaling back of infection testing. In doing so we run the risk of creating a data vacuum. Being able to test and undertake scientific surveillance of the virus’s future development would help us identify any future threats from new variants; particularly those classified as being “of concern”. What we should have learned from the past two years is that the ability to understand the virus and rapidly scale up our response is critical.

What is also now abundantly clear from the current data is that this is far from over and it is going to take some time for us to adapt as a society. The ongoing consequences for the most vulnerable sections of our society are still incredibly challenging. It will not be a surprise to any health professional that the pandemic was keenest felt in communities already negatively impacted by health inequalities. This has been the case ever since the publication of the “Black Report” (DHSS 1980), which showed in detail the extent to which ill-health and death are unequally distributed among the population of the UK. Indeed, there is evidence that these inequalities have been widening rather than diminishing since the establishment of the National Health Service in 1948. It is generally accepted that those with underlying health issues and therefore most at risk will be disproportionately located in socially deprived communities. Consequently, there is a genuine concern that the most vulnerable to the virus could be left behind in isolation as the rest of society moves on. However, we are now at a new critical moment which most will celebrate. Regardless of whether you believe the rolling back of restrictions is right or not, this moment in time allows us an opportunity to reflect on the past two years and indeed look forward to what has changed and what could happen in terms of both Coronavirus and any other future pandemic.

Looking back, I have no doubt that the last two years have changed life considerably in several positive and negative ways. Of course, we tend to migrate to the negative first and the overall cost of life, levels of infection and the long-term consequences have been immense. The longer-term implications of Covid (Long Covid) is still something we need to take seriously and fully understand. What is not in doubt is the toll this has had on individuals, families, communities and the future burden it places on our NHS. The psychological impact of social isolation and restrictions has been enormous and especially so for our children, young people, the vulnerable and the elderly. The social and educational development of school children is of particular concern. The wider economic implications of the pandemic will take some time to recover. Yet, whilst the negative implications cause us grave concern many features of our lives have improved. Many have identified that this pandemic has helped them re-asses what is important in life, how important key workers are in ensuring society continues to operate smoothly and the critical role health and social services must play in times of health crisis. Changing perspectives on work, work life balance and alternative ways of conducting business have been embraced and many argue that the world of work will never be the same again.

On that final note it’s important that as a society we have learned from what I have previously described as the greatest public health crisis in my lifetime. Pandemic planning was shown to be woefully inadequate and we must get this better because there is no doubt there will be another pandemic of this magnitude at some point in the future. Proper support for health and social services are critical and the state of the NHS at the start of all this was telling. Yes, it rose to the challenge as it always does but health and social care systems were badly let down in the early stages of this pandemic with disastrous consequences. Proper investment in science and research is paramount, for let’s be honest it was science that came to our rescue and did so in record time. There will inevitably be a large public enquiry into all aspects of the pandemic, its management and outcomes. We can only hope that lessons have been learned and we are better prepared for both the ongoing management of this pandemic and inevitably the next one.

Dr Stephen O’Brien

FHES

Originally posted here

Rule makers, rule breakers and the rest of us

There are plenty of theories about why rules are broken, arguments about who make the rules and about how we deal with rule breakers. We can discuss victimology and penology, navigating our way around these, decrying how victims and offenders are poorly treated within our criminal justice systems. We think about social justice, but it seems ignore the injustice perpetrated by some because we can somehow find an excuse for their rule breaking or point out some good deed somewhere along the line. And we lament at how some get away with rule breaking because of their status or power. But what is to be done about people that break the rules and in doing so cause or may cause considerable harm to others; to the rest of us?

Recently, Greece imposed a new penalty system upon those over 60 that are not vaccinated against Covid. Pensioners who have had real reductions in their pensions are now to be hit with a fine, a rolling fine at that, if they do not get vaccinated. This is against a backdrop of poor vaccination rates which seem to have improved significantly since the announcement of what many see as draconian measures by a right-wing government. There are those that argue that vaccination ought to be a choice, and this has been brought into focus by the requirements for health workers and those in the care profession to be vaccinated in this country. And we’ve heard arguments from industry against vaccination passports which would allow people to get into large venues and a consistent drip-drip effect of how damaging the covid rules are to the leisure industry and aviation, as well as the young people in society.

So, would it have been far more acceptable to have no rules at all around Covid? Should we have simply carried on and hoped that eventually herd immunity would kick in? Let’s not forget of course that the health service would have been so overwhelmed that many people will have died from illnesses other than Covid (they undoubtedly have to some extent anyway). The fittest will have survived and of course, the richest or most resourceful. Businesses will have been on their knees as workers failed to turn up for work, either because they were too ill or have moved on from this life and few customers will have thought about quaffing pints, clubbing, or venturing off to some faraway sunny place (not that they’d be particularly welcome there coming from plague island). It would have felt more like some Darwinian evolutionary experiment than civilised society.

It seems that making some rules for the good of society is necessary. Of course, there will be those that break the rules and as a society, we struggle to determine what is to be done with them. Fines are too harsh, inappropriate, draconian. Being caring, educating, works for some but let’s be honest, there are those that will break the rules regardless. Whilst we can argue about what should be done with those that break the rules, about the impact they have on society, about victims and crimes, perhaps the most pressing argument is about equality of justice. The rest of us, those that didn’t break the rules, might question how draconian the rules were (are) and we might question the punishments meted out to those that broke the rules. But what really hurts, where we really feel hard done by, let down, angry is to see that those that made the rules, broke the rules and for them we don’t get to consider whether the punishment is draconian or too soft. There are no consequences for the rule makers even when they are rule breakers. It seems a lamentable fact that we have a system of governance, be that situated in politics or business, that advocates a ‘do as I say’ rather than ‘do as I do’ mentality. The moral compass of those in power seems to be seriously misaligned. As the MP David Davis calls for the resignation of Boris Johnson and says that he has to go, he should look around and he might realise, they all need to go. This is not a case of one rotten apple, the whole crop is off, and it stinks to high heaven.