Home » Media

Category Archives: Media

Why I refuse to join the hate train

In a world drowning in outrage, where every headline screams division and every scroll brings fresh fury, it’s easy to forget something fundamental: there’s still beauty everywhere.

Turn on the news and you’re bombarded with it all—bans, blame, and bitter arguments about who’s ruining what. Immigrants, the wealthy, the homeless, the young, the benefits claimants—everyone’s apparently the problem. It’s a relentless tide of negativity and moaning that can sweep you under if you’re not careful.

But what if we chose differently?

Here are a few things I noticed in the last couple of weeks:

I came across a book that someone left on a park bench with a note: “Free to a good home.” On another late night, a man saw a mother struggling—baby in one arm, shopping bags in the other—and didn’t hesitate to help her to her car. And if you’re thinking “why didn’t she use a trolley?” then you’re part of the problem I’m talking about, because there were no trolleys in that shop.

In another moment, a homeless person was offering water to a runner who’d collapsed in the heat, providing comfort when it mattered most.

Elsewhere, a teacher stayed late for his “troubled” student preparing for exams. When I asked why, he said: “Everyone calls him destructive. I refuse to lose hope. He’s just a slower learner, and I’ll support him as long as it takes.”

In another event, teenagers on bikes formed a protective barrier around an elderly woman crossing the road.

Small acts. Quiet kindness. The stuff that never makes headlines, doesn't trend on social media, and doesn't fuel debates.

The truth is, these things happen everywhere, all the time. While we’re busy arguing about who’s destroying society, society is quietly rebuilding itself through a million small kindnesses. The coffee lady in the Learning Hub who remembers your order. The elderly doorman at Milton Keyens Costco who draws smiley faces on reciepts and hands them to children on their way out, just to see them smile. The neighbour who randomly helps pick up litter in the neighbourhood with her girls every Sunday afternoon. The friend who texts to check in with the simple words “how are you?”

The truth is simple: for every voice spreading hate, there are countless others spreading hope. For every person tearing down, there are builders, healers, and helpers working in the quiet spaces between the noise.

Yes, problems exist. Yes, challenges are real. But so is the grandfather teaching his grandson about dignity and respect. So is the aunty teaching her niece how to bake. So is the library volunteer reading to the shelter dogs. So is the community garden where strangers become neighbours.

Today, I’m choosing to notice the nice. Not because I’m naive, but because I refuse to let the moaning and the loudest voices drown out the most important ones. The ones that remind us we’re more alike than different. The ones that choose connection over division.

Your turn: What nice thing will you notice today? Free your mind, pay attention—you'll see one.

Because in a sea of anger, being gentle isn’t weak or naive—it’s revolutionary.

The future of criminology

If you have an alert on your phone then a new story may come with a bing! the headline news a combination of arid politics and crime stories. Sometimes some spicy celebrity news and maybe why not a scandal or two. We are alerted to stories that bing in our phone to keep ourselves informed. Only these are not stories, they are just headlines! We read a series of headlines and form a quick opinion of anything from foreign affairs, transnational crime, war, financial affairs to death. We are informed and move on.

There is a distinction, that we tend not to make whenever we are getting our headline alerts; we get fragments of information, in a sea of constant news, that lose their significance once the new headline appears. We get some information, but never the knowledge of what really happened. We hear of war but we hardly know the reasons for the war. We read on financial crisis but never capture the reason for the crisis. We hear about death, usually in crime stories, and take notice of the headcount as if that matters. If life matters then a single loss of life should have an impact that it deserves irrespective of origin.

After a year that forced me to reflect deeply about the past and the future, I often questioned if the way we consume information will alter the way we register social phenomena and more importantly we understand society and ourselves in it. After all crime stories tend to be featured heavily in the headlines. Last time I was imagining the “criminology of the future” it was terrorism and the use of any object to cause harm. That was then and now some years later we still see cars being used as weapons, fear of crime is growing according to the headlines that even the official stats have paused surveying since 2017! Maybe because in the other side of the Atlantic the measurement of fear was revealed to be so great that 70% of those surveyed admitted being afraid of crime, some of whom to the extent that changes their everyday life.

We are afraid of crime, because we read the headlines. If knowledge is power, then the fragmented information is the source of ambiguity. The emergence of information, the reproduction of news, in some cases aided by AI have not provided any great insight or understanding of what is happening around us. A difference between information and knowledge is the way we establish them but more importantly how we support them. In a world of 24/7 news updates, we have no ideological appreciation of what is happening. Violence is presented as a phenomenon that emerges under the layers of the dark human nature. That makes is unpredictable and scary. Understandably so…

This a representation of violence devoid of ideology and theory. What is violence in our society does not simply happens but it is produced and managed through the way it is consumed and promoted. We sell violence, package it for patriotic fervour. We make defence contracts, selling weapons, promoting war. In society different social groups are separated and pitted against each other. Territory becomes important and it can be protected only through violence. These mechanisms that support and manage violence in our society are usually omitted. A dear colleague quite recently reminded me that the role of criminology is to remind people that the origins of crime are well rooted in our society in the volume of harm it inflicts.

There is no singular way that criminology can develop. So far it appears like this resilient discipline that manages to incorporates into its own body areas of work that fiercely criticised it. It is quite ironic for the typical criminology student to read Foucault, when he considered criminology “a utilitarian discipline”! Criminology had the last laugh as his work on discipline and punishment became an essential read. The discipline seems to have staying power but will it survive the era of information? Most likely; crime data originally criticised by most, if not all criminologists are now becoming a staple of criminological research methods. Maybe criminology manages to achieve what sociology was doing in the late 20th century or maybe not! Whatever direction the future of criminology takes it will be because we have taken it there! We are those who ought to take the discipline further so it would be relevant in years to come. After all when people in the future asked you what did you do…you better have a good answer!

#UONCriminologyClub: What should we do with an Offender? with Dr Paula Bowles

You will have seen from recent blog entries (including those from @manosdaskalou and @kayleighwillis21 that as part of Criminology 25th year at UON celebrations, the Criminology Team have been engaging with lots of different audiences. The most surprising of these is the creation of the #UONCriminologyClub for a group of home educated children aged between 10-15. The idea was first mooted by @saffrongarside (who students of CRI1009 Imagining Crime will remember as a guest speaker this year) who is a home educator. From that, #UONCriminologyClub was born.

As you know from last week’s entry @manosdaskalou provided the introductions and started our “crime busters” journey into Criminology. I picked up the next session where we started to explore offender motivations and society’s response to their criminal behaviour. To do so, we needed someone with lived experience of both crime and punishment to help focus our attention. Enter Feathers McGraw!!!

At first the “crime busters” came out with all the myths: “master criminal” and “evil mastermind” were just two of the epithets applied to our offender. Both of which fit well into populist discourse around crime, but neither is particularly helpful for criminological study, But slowly and surely, they began to consider what he had done (or rather attempted to do) and why he might be motivated to do such things (attempted theft of a precious jewel). Discussion was fast flowing, lots of ideas, lots of questions, lots of respectful disagreement, as well as some consensus. If you don’t believe me, have a look at what Atticus and had to say!

We had another excellent criminology session this week, this time with Dr Paula Bowles. I think we all had a lot of fun, I personally could have enjoyed double or triple the session time. Dr Bowles was engaging, fun and unpretentious, making Criminology accessible to us whilst still covering a lot of interesting and complex subjects. We discussed so many different aspects of serious crime and moral and ethical questions about punishment and the treatment of criminals. During the session, we went into some very deep topics and managed to cover many big ideas. It was great that everyone was involved and had a lot to say. You might not necessarily guess from what I’ve said so far, how we got talking about Criminology in this way. It was all through the new Aardman animations film Wallace and Gromit: Vengeance Most Fowl and the cheeky little penguin or is it just a chicken? Feathers McGraw. Whether he is a chicken or a penguin, he gave us a lot to discuss such as whether his trial was fair or not since he can’t talk, if the zoo could really be counted as a prison and, if so was he allowed to be sent there without a trial? Deep ethical questions around an animation. Just like last time it was a fun and engaging lesson that made me want to learn more and more and I can’t wait for next time. (Atticus, 14)

What emerged was a nuanced and empathetic understanding of some key criminological debates and questions, albeit without the jargon so beloved of social scientists: nature vs. nurture, coercion and manipulation of the vulnerable, the importance of human rights, the role of the criminal justice system, the part played by the media, the impetus to punish to name but a few. Additionally, a deep philosophical question arose as to whether or not Aardman’s portrayal of Feathers’ confinement in a zoo, meant that as a society we treat animals as though they are criminals, or criminals as though they are animals. We are all still pondering this particular question…. After deciding as group that the most important thing was for Feathers to stop his deviant behaviour, discussions inevitably moved on to deciding how this could be achieved. At this point, I will hand over to our “crime busters”!

What to do with Feathers McGraw?

At first, I thought that maybe we should make prison a better place so that he would feel the need to escape less. It wouldn’t have to be something massive but just maybe some better furniture or more entertainment. Also maybe make the security better so that it would be harder to break out. If we imagine the zoo as the prison, animals usually stay in the zoo for their life so they must have done some very bad stuff to deserve a life sentence! Is it safe to have dangerous animals so close to humans? Feathers McGraw might get influenced by the other prisoners and instead of getting better he might get more criminal ideas. I believe there should be a purpose-built prison for the more dangerous criminals, so they are kept away from the humans and the non-violent criminals. in this case is Feathers considered a violent or non-violent criminal? Even though he hasn’t killed anyone, he has abused them, tried to harm them, hacked into Wallace’s computer, vandalised gardens through the Norbots, and stole the jewel. So, I think we should get a restraining order against Feathers McGraw to stop him from seeing Wallace and Gromit. I also think we should invest in therapy for Feathers to help him realise that he doesn’t need to own the jewel to enjoy it, what would he even do with it?! Maybe socializing could also help to maybe take his mind of doing criminal things. He always seems alone and sad. I’m not sure whether he will be able to change his ways or not but I think we should do the best we can to. (Paisley, 10)

I think in order to stop Feathers McGraw’s criminal behaviour, he should go to prison but while he is there, he should have some lessons on how to be good, how to make friends, how to become a successful businessman (or penguin!), how to travel around on public transport, what the law includes and what the punishments there are for breaking it etc. I also think it’s important to make the prisons hospitable so that he feels like they do care about him because otherwise it might fuel anger and make him want to steal more diamonds. At the same time though, it should not be too nice so that he’ll think that stealing is great, because if you don’t get caught, then you keep whatever you stole and if you do get caught then it doesn’t matter because you will end up staying in a luxury cell with silky soft blankets.

After he is released from prison, I would suggest he would be held under house arrest for 2-3 months. He will live with Wallace and Gromit and he will receive a weekly allowance of £200. With this money, he will spend:

£100 – Feathers will pay Wallace and Gromit rent each week,

£15-he will pay for his own clothes,

£5-phone calls,

£10-public transport,

£35-food,

£5-education,

£15-hygiene,

£15- socialising and misc.

During this time, Feathers could also be home educated in the subjects of Maths, English etc. He should have a schedule so he will learn how to manage his time effectively and eventually should be able to manage his timewithouta schedule. The reason for this is because when Feathers was in prison, he was told what to do every day and at what time he would do it. He now needs to learn how to make those decisions by himself. This would mean when his house arrest is finished, he can go out into the real world and live happy life without breaking the law or stealing. (Linus, 13)

I think that once Feathers McGraw has been captured any money that he has on him will be taken away as well as any disguises that he has and if he still has any belongings left they will be checked to see whether he can have them. After that he should go to a proper prison and not a Zoo, then stay there for 3 months. Once a week, while he is in prison a group of ten penguins will be brought in so that he can be socialised and learn manners and good behaviour from them. However they will be supervised to make sure that they don’t come up with plans to escape. After that he will live with a police officer for 3 years and not leave the house unless a responsible and trustworthy adult accompanies him until he becomes trustworthy himself. He will be taught at the police officers house by a tutor because if he went to school he might run away. Feathers McGraw will have a weekly allowance of £460 that is funded by the government as he won’t have any money. Any money that was taken away from him will be given back in this time. Any money left over will be put into his savings account or used for something else if the money couldn’t quite cover it.

In one week he will give

£60 for fish and food

£10 for travel

£50 for clothing but it will be checked to make sure that it isn’t a disguise.

£80 for the police officer that looking after him

£15 for necessities (tooth brush, tooth paste, face cloth etc…)

£70 for his tutor

£55 for education supplies

£20 will be put in a savings account for when he lives by himself again.

And £100 for some therapy

After 1 year if the police officer looking after him thinks that he’s trustworthy enough then he can get a job and use £40 pounds a week (if he earns manages to earn that much.) as he likes and the rest of it will be put into his savings account. Feathers McGraw will only be allowed to do certain jobs for example, He couldn’t be a police officer in case he steals something that he’s guarding, He also couldn’t be a prison guard in case he helped someone escape etc… If at any point he commits another crime he will lose his freedom and his job and will be confined to the house and garden. When he lives by himself again he will have to do community service for 1 month. (Liv, 11).

Feathers McGraw has committed many crimes, some of which include attempted theft, abuse towards Wallace and Gromit, and prison break.

Here are some ideas of things that we can do to stop him from reoffending:

Immediate action:

A restraining order is to be put in place so he can’t come within 50m of Wallace and Gromit, for their protection both physical and mental. Penguins live for up to 20 years so seeing as he is portrayed as being an adult, my guess is he is around 10 years old. His sentence should be limited to 2 years in prison. Whilst serving his sentence he should be given a laptop (with settings so that he can’t use it to hack) so he can write, watch videos, play games and learn stuff.

Longer term solutions:

When Feathers gets out he will be banned from seeing the gem in museums so there will be less chance of him stelling it. He also will be given some job options to help him get started in his career. His first job won’t be front facing so Wallace and Gromit won’t have to be worried and they will get to say no to any job Feathers tries to get. If he reoffends, he will be taken to court where his sentence will be a minimum of 5 years in prison.

Rehabilitation:

I think Feathers should be given rehabilitation in several different forms, some sneakier than others! One of these forms is probation: penguins which are trained probation officers who will speak to him and try to say that crime is not cool. To him they will look like normal penguins, he won’t know that they have had training. He also should be offered job experience so he can earn a prison currency which he can use to buy upgrades for his cell (for example a better bed, bigger tv, headphones, an mp3 player and songs for said mp3 player) to give him a chance to get a job in the future. (Quinn, 12)

The “crime busters” comments above came after reflecting on our session, their input demonstrates their serious and earnest attempt to resolve an extremely complex issue, which many of the greatest minds in Criminology have battled with for the last two centuries. They may seem very young to deal with a discipline often perceived as dark, but they show us an essential truth about Criminology, it is always hopeful, always focused on what could be, instead of tolerating what we have.

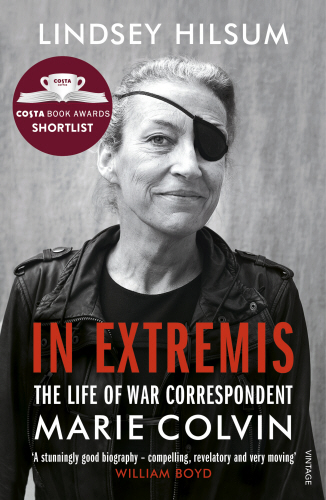

A review of In-Extremis: The Life of War Correspondent Marie Colvin

Recently, I picked up a book on the biography of Marie Colvin, a war correspondent who was assassinated in Syria, 2012. Usually, I refrain from reading biographies, as I consider many to be superficial accounts of people’s experiences that are typically removed from wider social issues serving no purpose besides enabling what Zizek would call a fetishist disavowal. It is the biographies of sports players and singers, found on the top shelves of Waterstones and Asda that spring to mind. In-Extremis, however, was different. I consider this book to be a very poignant and captivating biography of war correspondent Marie Colvin, authored by fellow journalist Lindsey Hilsum. The book narrates Marie’s life before her assassination. Her early years, career ventures, intimate relationships, friendships, and relationships with drugs and alcohol were all discussed. So too were the accounts of Marie’s fearless reporting from some of the world’s most dangerous conflict zones, including Sri-Lanka, Iraq, Lebanon, and Syria. Hilsum wrote on the events both before Marie’s exhilarating career and during the peak of her war correspondence to illustrate the complexities in her life. This reflected on Marie’s insatiability of desire to tell the truth and capture the voices of those who are absent from the ‘script’. So too, reporting on the emotions behind war and conflict in addition to the consistent acts of personal sacrifice made in the name of Justice for the disenfranchised and the voiceless.

Across the first few chapters, Hilsum wrote on the personal life of Marie- particularly her traits of bravery, resilience, persistence, and an undying quest for the truth. Hilsum further delved into the complexities of Marie’s personality and life philosophies. A regular smoker, drinker and partygoer with a captivating personality that drew people in were core to who Marie was according to Hilsum. However, the psychological toils of war reporting became clear, particularly as later in the book, the effects of Marie’s PTSD and trauma began to present itself, particularly after Marie lost eyesight in her left eye after being shot in Sri-Lanka. The eye-patch worn by Marie to me symbolised the way she carried the burdens of her profession and personal vulnerabilities, particularly between maintaining her family life and navigating her occupational hazards.

In writing this biography, Hilsum not only mapped the life of one genuinely awesome and inspiring woman, but also highlighted the importance of reporting and capturing the voices of the casualties of war. Much of her work, I felt resonated with my own. As an academic researcher, it is my job to research on real-life issues and to seek the truth. I resonated with Marie’s quest for the truth and strongly aligned myself to her principles on capturing the lived experiences of those impacted by war, conflict, and social justice issues. These people, I consider are more qualified to discuss these issues than those of us who sit in the ivory towers of institutions (me included!).

Moreover, I considered how I can be more like Marie and how I can embed her philosophies more so into my own research… whether that’s through researching with communities on the cost-of-living crisis or disseminating my research to students, fellow academics, policymakers, and practitioners. I feel inspired and moving forward, I seek to embody the life and spirit of Marie and thousands of other journalists and academics who work tirelessly to research on and understand the truth to bring forward the narratives of those who are left behind and discarded by society in its mainstream.

The Problem with True Crime

There has been a huge spike in interest in true crime in recent years. The introduction to some of the most notorious crimes have been presented on Netflix and other streaming platforms, that has further reinforced the human interest in the gore of violent crimes.

Recently I went to the theatre to watch a show title the Serial Killer Next Door, which highlights some of the most notorious crimes to sweep the nation. From the Toy Box Killer (David Ray-Parker) and his most brutal violence against women to Ed Kemper and the continuous failing by the FBI to bring one of the most violent and prolific killers to justice. While I was horrified by the description both verbal and photographic of the crimes committed, by the serial killers. I was even more shocked at the reaction of the audience and how the cases were presented. The show attempted to sympathise with the victims but this fell short as the entertainment value of the audience was paramount and thus, the presenter honed in on the ‘comedic’ factor of the criminal and the crimes committed. Graphic pictures of the naked bodies of men, women and children brutalised at the hands of the most sadistic monsters were put on screens for speculation and entertainment. Audience members enjoyed popcorn and crisps while lapping up the horror displayed.

I did not stay for the full show…..

The level of distaste was too much for me but from what I did watch made me reflect deeply and led me to the age-old topic among criminologists and victimologists that question where the victims are and why do they continue to be dehumanised. Victims of these heinous crimes are rarely remembered and depicted in a way that moves them away from being viewed as human and instead commodities and after thoughts of crime.

The true crime community on YouTube has been criticized for the sensationalist approach crime. With niche story telling while applying one’s makeup and relaying the most brutal aspects of true crime cases to audiences. I ask the question when and how did we get to this point in society where entertainment trumps victims and their families. Later, this year I will be bringing this topic to a true crime panel to further explore the damage that this type of entertainment has on both the consumer and the victim’s legacy. The dehumanisation of victims and desensitisation of consumers for entertainment tells us something about the society we live in that should be addressed…..I am sure there will be other parts to this post that will explore the issues with true crime and its problematic and exploitative nature.

Media Madness

Unless you have been living under a rock or on a remote island with no media access, you would have been made aware of the controversy of Russell Brand and his alleged ‘historic’ problematic behaviour. If we think about Russell Brand in the early 2000s he displayed provocative and eccentric behaviour, which contributed to his rise to fame as a comedian, actor, and television presenter. During this period, he gained popularity for his unique style, which combined sharp wit, a proclivity for wordplay, and a rebellious, countercultural persona.

Brand’s stand-up comedy routines was very much intertwined with his personality, which was littered with controversy, something that was welcomed by the general public and bosses at big media corporations. Hence his never-ending media opportunities, book deals and sell out shows.

In recent years Brand has reinvented (or evolved) himself and his public image which has seen a move towards introspectivity, spirituality and sobriety. Brand has collected millions of followers that praise him for his activist work, he has been vocal on mental health issues, and he encourages his followers to hold government and big corporations to an account.

The media’s cancellation of Russell Brand without any criminal charges being brought against him raises important questions about the boundaries of cancel culture and the presumption of innocence. Brand, a controversial and outspoken comedian, has faced severe backlash for his provocative statements and unconventional views on various topics. While his comments have undoubtedly sparked controversy and debate, the absence of any criminal charges against him highlights the growing trend of public figures being held to account in the court of public opinion, often without a legal basis.

This situation underscores the importance of distinguishing between free speech and harmful behaviour. Cancel culture can sometimes blur these lines, leading to consequences that may seem disproportionate to the alleged transgressions. The case of Russell Brand serves as a reminder of the need for nuanced discussions around cancel culture, ensuring that individuals are held accountable for their actions while also upholding the principle of innocent until proven guilty in a court of law. It raises questions about how society should navigate the complex intersection of free expression, public accountability, and the potential consequences for individuals in the public eye.

There is also an important topic that seems to be forgotten in this web of madness……..what about the alleged victims. There seems to be a theme that continuously needs to be highlighted when criminality and victimisation is presented. There is little discussion or coverage on the alleged victims. The lack of media sensitivity and lay discussion on this topic either dehumanises the alleged victims by using lines such as ‘Brand is another victim of MeToo’ and comparing him to Cliff Richard and Kevin Spacey, two celebrities that were accused of sexual crimes and were later found not guilty, which in essence creates a narrative that does not challenge Brand’s conduct, on the basis of previous cases that have no connection to one another.

We also need to be mindful on the medias framing of the alleged witch hunt against Russell Brand and the problematic involvement that the UK government. The letter penned by Dame Dinenage sent to social media platforms in an attempt to demonetize Brand’s content should also be highlighted. While I support Brand being held accountable for any proven crimes he has committed, I feel these actions by UK government are hasty, and problematic considering there have been many opportunities for the government to step in on serious allegations about media personalities on the BBC and other news stations and they have not chosen to act. The step made by Dame Dinenage has contributed to the media madness and contributes to the out of hand and in many ways, nasty discussion around freedom of speech. The government’s involvement has deflected the importance of the victimisation and criminality. Instead, it has replaced the discussion around the governments overarching punitive control over society.

Brand has become a beacon of understanding to is 6.6 million followers during Covid 19 lockdowns, mask mandates and vaccinations. This was at a time when many people questioned government intentions and challenged the mainstream narratives around autonomy. Because Brand has been propped up as a hero to his ‘awakened’ followers the shift around his conduct and alleged crimes have been erased from conversation and debates around BIG BROTHER and CONTROL continue to shape the media narrative………

The True Crime Genre and Me

I have always enjoyed the true crime genre, I enjoyed the who dunnit aspect that the genre feeds into, I also enjoyed “learning” about these crimes, and why people committed them. I grew up with an avid interest in homicide, and the genre as a result. So, studying criminology felt like it was the best path for me. Throughout the three years, this interest has stayed with me, resulting in me writing my dissertation on how the true crime genre presents homicide cases, and how this presentation influences people’s engagement with the genre and homicides in general.

With this being my main interest within the field of criminology, it was natural that True Crime and Other Fictions (CRI1006) module in first year caught my attention. This module showed me that my interest can be applied to the wider study of criminology, and that the genre does extend into different areas of media and has been around for many years. Although this module only lasted the year, and not many other modules- at least of the ones that I took- allowed me to continue exploring this area, the other modules taught me the skills I would need to explore the true crime genre by myself. Something- in hindsight- I much prefer.

I continued to engage with the wider true crime genre in a different way than I did before studying criminology- using the new skills I had learnt. Watching inaccurate and insensitive true crime dramas on Netflix, watching YouTubers doing their makeup whilst talking about the torture of a young girl, podcasts about a tragic loss a family suffered intercut with cheery adverts. This acts as a small snapshot of what the genre is really like, whereas when I originally engaged with it, it was simple retellings of a range of cases, each portrayed in slightly different ways- but each as entertaining as the next. To me, I think this is where the genre begins to fall apart, when the creators see what they are producing as entertainment, with characters, rather than retellings of real-life events, that affects real people.

Having spent so much time engaging with the genre and having the skills and outlook that comes with studying criminology, you can’t help but to be critical of the genre, and what you are watching. You begin to look at the reasoning behind why the creators of this content choose to present it in such ways, why they skip out on key pieces of information. It all makes a bit more sense. Its just entertainment. A sensationalist retelling of tragic events.

Although studying criminology may have ruined how I enjoy my favourite genre of media, it also taught me so many skills, and allowed me to develop my understating in an area I’ve always been interested in. These skills can be applied in any area, and I think that is the biggest take away from my degree. Considering I now work as the Vice President of Welfare at the Students Union– and getting some odd looks when I say what my degree was- I have no regrets. Even if I walk away from my time at university and never use the knowledge I gained from my studies, I can walk away and know that my time was not wasted, as the skills I have learnt can be applied to whatever I do moving forward.