Home » Law

Category Archives: Law

The Caracas Job: International Law and Geo-Political Smash and Grab

So, they actually did it, eh?

It’s January 2026, and I, for one, am still trying to remember my work logins and wondering if this is the year that Aliens invade Earth. Yet, across the pond, the Americans have decided to kick off the New Year with a throwback classic: decapitating a sovereign Latin-American government.

Adiós Maduro. We hardly know yer pal. Well, we all knew you enough to know you were a disastrous authoritarian kleptocrat who managed to bankrupt a country sitting on a lake of oil. But we need to talk about how it happened, because if you listen carefully enough to the wind wuthering through the empty corridors of the UN Building in New York, you can probably hear the death rattle of what I once studied and was quaintly entitled, ‘Rules-Based International Order’-aka International Law.

As one colleague and our very own Dr Manos Daskolou pointed out to me this very day, it’s almost eighty years since 1945. Eight decades of pretending we built a civilised global architecture out of the ashes of World War II. We built tribunals in The Hague, we wrote very sternly worded Geneva Conventions, and we created a Security Council where superpowers could veto each other into paralysis. It was a lovely piece of Geo-Political theatre.

The days-old removal of the Venezuelan head of state by direct US intervention isn’t just a deviation from the norm: it’s a flagrant breach of the foundational prohibition on the ‘use of force’ found in Article 2(4) of The UN Charter. The mask has slipped, and underneath it is just raw, naked power.

As a Brit observing this rigmarole from the very cold and soggy sidelines, it’s hard not to view this from a very specific lens. We invented modern imperialism, after all. Criminologists will often discuss concepts like State Crimes. They will often question who indeed polices the Police?

If I decide to kick down my neighbour’s door because I don’t like the way she runs her household, steal her assets and install her sister as the new head of the family, I’m going to court. I am a burglar, a thug and a violent criminal. If a superpower does the same thing to a sovereign nation, they get a press conference at Mar-a-Lago.

For eighty years, the West has been incredibly successful at labelling its own interventions as ‘police actions’ or ‘humanitarian missions’, all the while labelling acts of rivals as ‘aggression’. The Caracas job is the ultimate expression of this.

Listen to the rhetoric coming out of Washington right now. It’s textbook gaslighting. ‘Maduro was a tyrant’, ‘Other countries do worse’, i.e condemning the condemners. They certainly are not arguing that entry into Caracas was legal under the UN Charter was legal because it most definitely wasn’t. They are arguing that the law should not apply to them because their intentions were pure.

Deja Vu-Iraq

The darkest irony of the Venezuelan decapitation is the crushing sense of deja vu. We cannot talk about removing a dictator in the 2020s without flashbacks to Saddam Hussein and Dr David Kelly entering the scene. The parallels are screaming at us. In 2003, the justification for taking Saddam (and, sadly, Dr Kelly as a direct result) out was a cocktail of WMD lies and dangerous rhetoric. As the Chilcot Report stated years ago, the legal basis for military action against Iraq was ‘far from satisfactory’.

The critical failure in Iraq and the one we are doomed to repeat in Venezuela is that it is terrifyingly easy for a superpower like the USA to smash a second-rate military. The hard part is what on earth comes next?

Perhaps it would have been better for the superpowers to manipulate Maduro’s own people, taking him out, so to speak. Organic change in any situation lends legitimacy that enforced or imported change never does. When you decapitate a state at 30,000 feet, you create a vacuum. The USA may have created a dependency, effectively violating the principle of self-determination, which is enshrined in the Human Rights Convention.

The Iranian Elephant In The Room

Of course, none of this is actually happening in a vacuum. Being a Yorkshire lass with Middle Eastern Heritage, I am keenly aware of the politics of the regions hitting the headlines on an almost daily basis. Yet, no one has to have bloodline ties to any of the countries or regions involved to see the obvious Elephant in the room. It’s that flipping obvious. Maduro wasn’t just an irritant because of his economy-crashing style. It was a strategic flipping of the bird for America’s rivals-Crucially, Iran. This is where the narrative gets even darker. This is gang warfare.

The danger here is escalation. If Tehran decides that the fall of Maduro constitutes a direct challenge to its own deterrence strategy, it will not retaliate in the Caribbean. They are likely (if history has taught us anything) to retaliate in the Strait of Hormuz. The butterfly effect of a regime change in Caracas could easily result in the closure of the Suez Canal. Yes, that old chestnut.

The old guard loved International Law. They loved it because they knew how to manipulate it. They used the UN Council like a skilled Barrister uses a loophole. They built coalitions. The current approach-Let’s call it ‘Act Now Think Later Diplomacy’ dispenses with the formalities and paperwork. It sees International Law NOT as a tool to be manipulated, but as an annoying restraint to be ignored. It confirms the narrative that the Nuremberg trials were merely ‘Victors’ Justice’, a system where legal accountability is the privilege of the defeated.

The difference between Putin invading Ukraine and the USA decapitating Venezuela is rapidly becoming a distinction without a difference.

So, here we go in 2026. The powerful have shown they don’t give a toss about the rules. They’ve shown that ‘sovereignty’ is just a word they use in speeches, not really a word they respect.

When people stop believing in the legitimacy of the law, they usually stop following it. We are about to see what happens when the entire world stops believing in the legitimacy of International Law.

It is going to be a messy few decades. Cheers, mine’s a double.

UK Justice v The Demonic and Others

The sanctity of a civilised court room demands rationality, but the laws of the distant and not so distant past in this jurisdiction are entrenched in the uncanny. Rules safeguarding the impartiality of the jury are grim “wards” against the spiritual chaos that once dictated verdicts. The infamous case of the Ouija Board jurors, aka R v Young[i] only thirty years ago is not merely a legal curiosity: it is a modern chilling echo of a centuries old struggle defining the judiciary’s absolute commitment to a secular process that refuses to share its authority with the spectral world. The ancient rule, now applied to Google and the smartphone, has always been simple: the court cannot tolerate a decision derived from an unvetted external source.

When Law Bowed To The Supernatural-Ancient Past?

For millennia, the outcome of a criminal trial in Britain was terrifyingly dependent on the supernatural, viewing the legal process as a mechanism for Divine Judgement[ii]. The state feared the power of the otherworldly more than it trusted human evidence.

Prior to the 13th century, the determination of guilt was not based on evidence but on the Judicium Dei [iii](Judgement of God). The accused’s fate lay not with the court but with the elements of the earth itself.

The Ordeal of Hot Iron: The accused would carry a piece of red-hot iron. If their subsequent wound was judged “unclean” after three days-a sign of God withholding his grace-the accused was condemned to death. The burden of proof was literally placed upon a miracle.

The Ordeal of Cold Water: This was an essential test in early witch-finding. If the bound accused floated, the pure water was thought to reject them as impure agents of the Devil, condemning them as guilty. The collapse of these ordeals after the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215 was the first, forced act of separation between the secular law and the spiritual realm, necessitating the creation of a human, rational jury[iv]

Legislating against the Demonic: The Witchcraft Acts

Even after the rise of the jury, the judiciary was consumed by the fear of the demonic. The Act against Conjuration, Witchcraft and dealing with evil and wicked Spirits 1604 (1 Jas.4 1. c. 12)[v] made contacting the demonic a capital felony, ensuring that the courtroom remained a battleground against perceived occult evil.

The Pendle Witch Trials (1612): This event is a spectral stain on UK legal history. Ten people were executed based on testimony that included spectral evidence, dreams, and confessions extracted under duress. The judges and juries legally accepted that the Devil and his agents had caused tangible harm. The failure to apply any rational evidential standards resulted in judicial murder.[vi]

Even the “rational” repeal in the Witchcraft Act 1735 (9 Geo. 2. c. 5),[vii] which only criminalised pretending to use magic (fraud), haunted the system. The prosecution of medium Helen Duncan in 1944 under this very Act, for deceiving the public with her spiritualist services, demonstrated that the legal system was still actively policing the boundaries of the occult well into the modern era, fearful of supernatural deceit if not genuine power.

The Modern Séance: R v Young and the Unholy Verdict

The 1994 murder trial of Stephen Young[viii], accused of the double murder of Harry and Nicola Fuller, brought the full weight of this historical conflict back into the spotlight. The jury, isolated and burdened with the grim facts of the case, succumbed to an uncanny primal urge for absolute certainty.

The jury had retired to a sequestered hotel to deliberate the grim facts of the double murder.During a break in deliberations on the Friday night, four jurors initiated a makeshift séance in their hotel room. They used paper and a glass to fashion a crude Ouija board, placing their life-altering question to the “spirits” of the deceased victims, Harry and Nicola Fuller.

The glass, according to the jurors’ later testimony, moved and chillingly spelled out the words “STEPHEN YOUNG DONE IT.”

The Court of Appeal, led by Lord Taylor CJ, ruled that the séance was a “material irregularity” because it took place outside the official deliberation room (in the hotel). This activity amounted to the reception of extrinsic, prejudicial, and wholly inadmissible evidence after the jury had been sworn. The verdict was quashed because a system based on proof cannot tolerate a decision derived from ‘the other side’

The core rule remains absolute: the verdict must be based only on the facts presented in court. The modern threat to this principle is not possession by a demon, but digital contamination, a risk the law now treats as functionally identical to the occult inquiry of 1994.

The Digital Contamination: R v Karakaya[ix]

The Criminal Justice and Courts Act 2015 (CJCA 2015) was the formal legislative “ward” against the digital equivalent of the séance.

The New Medium: In the 2018 trial of Huseyin Karakaya, a juror used a mobile phone to research the defendant’s previous conviction. The smartphone became the unauthorised medium. The Legal Equivalence: The Juries Act 1974, s 20A (inserted by CJCA 2015)[x] makes it a criminal offence for a juror to intentionally research the case. In the eyes of the law, consulting Google for “defendant’s past” is legally equivalent to consulting a ghost for “who done it.” Both are dangerous acts of unauthorized external inquiry.

The Court of Appeal, in R v Karakaya quashed the conviction because introducing external, inadmissible evidence (like a prior conviction) created a real risk of prejudice, fundamentally undermining the fair trial principle raised in Young.

The lesson of the Ouija Board Jurors and the digital contamination in R v Karakaya is a chilling warning from the past: the moment the courtroom accepts an external, unverified source—be it a spirit or a search engine—the entire structure of rational justice collapses, bringing back the judicial catastrophe of the Pendle Trials. In 2025, the UK criminal justice system continues to fight the ghosts of superstition, ensuring the verdict is determined by the cold, impartial scrutiny of the facts.

[i] R v Young [1995] QB 324

[ii]R Bartlett, Trial by Fire and Water: The Medieval Judicial Ordeal (Oxford University Press 1986). (https://amesfoundation.law.harvard.edu/lhsemelh/materials/BartlettTrialByFireAndWater.pdf)

[iii] J G Bellamy, The Criminal Law of England 1066–1307: An Outline (Blackwell 1984) p42

[iv] Margaret H. Kerr, Richard D. Forsyth, Michael J. Plyley

The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, Vol. 22, No. 4 (Spring, 1992), pp. 573-595

[v] https://archives.blog.parliament.uk/2020/10/28/which-witchcraft-act-is-which/

[vi] https://www.historic-uk.com/CultureUK/The-Pendle-Witches/

[vii] Witchcraft Act 1735 (9 Geo. 2. c. 5) https://statutes.org.uk/site/the-statutes/eighteenth-century/1735-9-george-2-c-5-the-witchcraft-act/

[viii] R v Young [1995] QB 324

[ix] R v Karakaya[ 2020] EWCA Crim 204

[x]The Juries Act 1974, s 20A https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1974/23/section/20A

Exploring the National Museum of Justice: A Journey Through History and Justice

As Programme Leader for BA Law with Criminology, I was excited to be offered the opportunity to attend the National Museum of Justice trip with the Criminology Team which took place at the back end of last year. I imagine, that when most of us think about justice, the first thing that springs to mind are courthouses filled with judges, lawyers, and juries deliberating the fates of those before them. However, the fact is that the concept of justice stretches far beyond the courtroom, encompassing a rich tapestry of history, culture, and education. One such embodiment of this multifaceted theme is the National Museum of Justice, a unique and thought-provoking attraction located in Nottingham. This blog takes you on a journey through its historical significance, exhibits, and the essential lessons it imparts and reinforces about justice and society.

A Historical Overview

The National Museum of Justice is housed in the Old Crown Court and the former Nottinghamshire County Gaol, which date back to the 18th century. This venue has witnessed a myriad of legal proceedings, from the trials of infamous criminals to the day-to-day workings of the justice system. For instance, it has seen trials of notable criminals, including the infamous Nottinghamshire smuggler, and it played a role during the turbulent times of the 19th century when debates around prison reform gained momentum. You can read about Richard Thomas Parker, the last man to be publicly executed and who was hanged outside the building here. The building itself is steeped in decade upon decade of history, with its architecture reflecting the evolution of legal practices over the centuries. For example, High Pavement and the spot where the gallows once stood.

By visiting the museum, it is possible to trace the origins of the British legal system, exploring how societal values and norms have shaped the laws we live by today. The National Museum of Justice serves as a reminder that justice is not a static concept; it evolves as society changes, adapting to new challenges and perspectives. For example, one of my favourite exhibits was the bench from Bow Street Magistrates Court. The same bench where defendants like Oscar Wilde, Mick Jagger and the Suffragettes would have sat on during each of their famous trials. This bench has witnessed everything from defendants being accused of hacking into USA Government computers (Gary McKinnon), Gross Indecency (Oscar Wilde), Libel (Jeffrey Archer), Inciting a Riot (Emmeline Pankhurst) as well as Assaulting a Police Officer (Miss Dynamite).

Understanding this rich history invites visitors to contextualize the legal system and appreciate the ongoing struggle for a just society.

Engaging Exhibits

The National Museum of Justice is more than just a museum; it is an interactive experience that invites visitors to engage with the past. The exhibits are thoughtfully curated to provide a comprehensive understanding of the legal system and its historical context. Among the highlights are:

1. The Criminal Courtroom: Step into the courtroom where real trials were once held. Here, visitors can learn about the roles of various courtroom participants, such as the judge, jury, and barristers. This is the same room that the Criminology staff and students gathered in at the end of the day to share our reflections on what we had learned from our trip. Most students admitted that it had reinforced their belief that our system of justice had not really changed over the centuries in that marginalised communities still were not dealt with fairly.

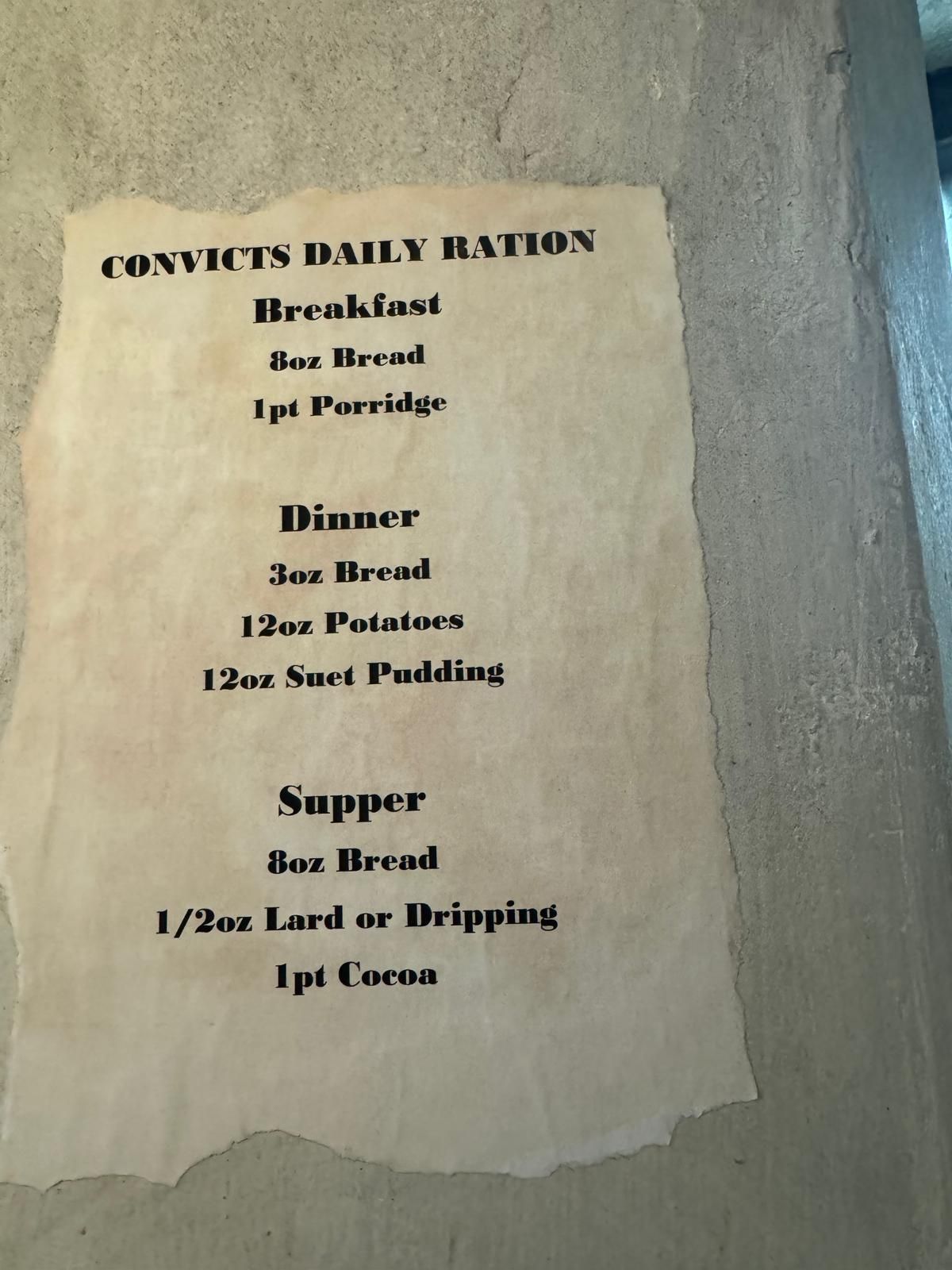

2. The Gaol: We delved into the grim reality of life in prison during the Georgian and Victorian eras. The gaol section of the gallery offers a sobering look at the conditions inmates faced, emphasizing the societal implications of punishment and rehabilitation. For example, every prisoner had to pay for his/ her own food and once their sentence was up, they would not be allowed to leave the prison unless all payments were up to date. The stark conditions depicted in this exhibit encourage reflections on the evolution of prison systems and the ongoing debates surrounding rehabilitation versus punishment. Eventually, in prisons, women were taught skills such as sewing and reading which it was hoped may better their chances of a successful life in society post release. This was an evolution within the prison system and a step towards rehabilitation of offenders rather than punishment.

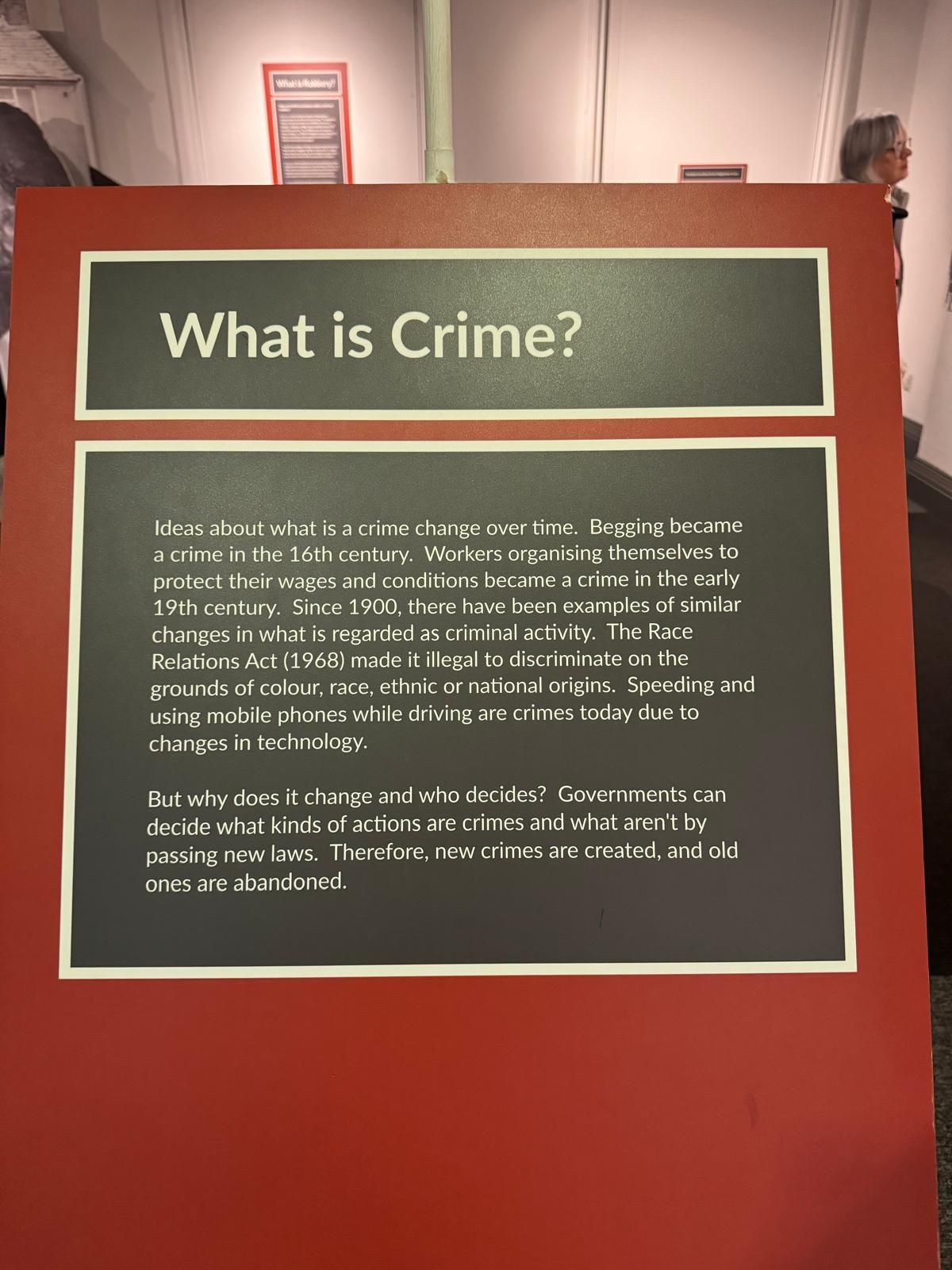

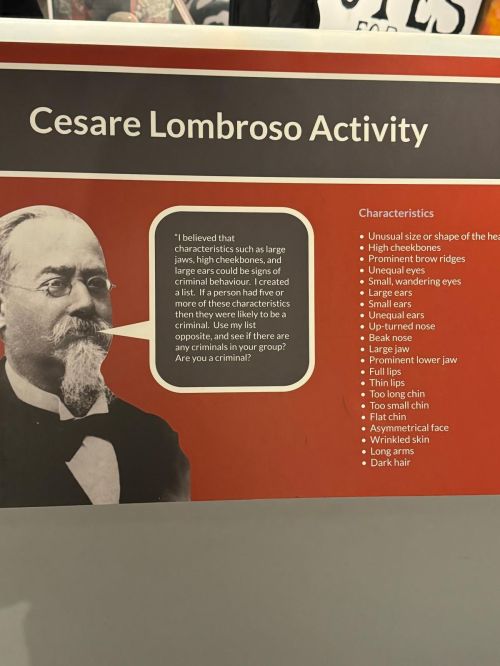

3. The Crime and Punishment Exhibit: This exhibit examines the relationship between crime and society, showcasing the changing perceptions of criminal behaviour over time. For example, one famous Criminologist of the day Cesare Lombroso, once believed that it was possible to spot a criminal based on their physical appearance such as high cheekbones, small ears, big ears or indeed even unequal ears. Since I was not familiar with Lombroso or his work, I enquired with the Criminology department as to studies that he used to reach the above conclusions. Although I believe he did carry out some ‘chaotic’ studies, it really reminded me that it is possible to make statistics say whatever it is you want them to say. This is the same point in relation to the law generally. As a lawyer I can make the law essentially say whatever I want it to say in the way I construct my arguments and the sources I include. Overall, The Inclusions of such exhibits raises and attempts to tackle difficult questions about personal and societal morality, justice, and the impact of societal norms on individual actions. By examining such leading theories of the time and their societal reactions, the exhibit encourages visitors to consider the broader implications of crime and the necessity of reform within the justice system. Do you think that today, deciding whether someone is a criminal based on their physical appearance would be acceptable? Do we in fact still do this? If we do, then we have not learned the lessons from history or really moved on from Cesare Lombroso.

Lessons on Justice and Society

The National Museum of Justice is not merely a historical site; it also serves as a platform for discussions about contemporary issues related to justice. Through its exhibits and programs, our group was invited to reflect on essentially- The Evolution of Justice: Understanding how laws have changed (or not!) over time helps us appreciate the progress (or not!) made in human rights and justice and with particular reference to women. It also encourages us to consider what changes may still be needed. For example, we were incredibly privileged to be able to access the archives at the museum and handle real primary source materials. We, through official records followed the journey of some women and girls who had been sent to reform schools and prisons. Some were given extremely long sentences for perhaps stealing a loaf of bread or reel of cotton. It seemed to me that just like today, there it was- the huge link between poverty and crime. Yet, what have we done about this in over two or three hundred years? This focus on historical cases illustrates the importance of learning from the past to inform present and future legal practices.

– The Importance of Fair Trials: The gallery emphasizes the significance of due process and the presumption of innocence, reminding us that justice must be impartial and equitable. In a world where public opinion can often sway perceptions of guilt or innocence, this reminder is particularly pertinent. The National Museum of Justice underscores the critical role that fair trials play in maintaining the integrity of the legal system. For example, if you were identified as a potential criminal by Cesare Lombroso (who I referred to above) then you were probably not going to get a fair trial versus an individual who had none of the characteristics referred to by his studies.

– Societal Responsibility: The exhibits prompt discussions about the role of society in shaping laws and the collective responsibility we all share in creating a just environment. The National Museum of Justice encourages visitors to think about their own roles in advocating for justice, equality, and reform. It highlights that justice is not solely the responsibility of legal professionals but also of the community at large.

– Ethics and Morality: The museum offers a platform to explore ethical dilemmas and moral questions surrounding justice. Engaging with historical cases can lead to discussions about right and wrong, prompting visitors to consider their own beliefs and biases regarding justice.

Conclusion

The National Museum of Justice in Nottingham is a remarkable destination that beautifully intertwines history, education, and advocacy for justice. By exploring its rich exhibits and engaging with its thought-provoking themes, visitors gain a deeper understanding of the complexities surrounding justice and its vital role in society. Whether you are a history buff, a legal enthusiast, a Criminologist or simply curious about the workings of justice, the National Museum of Justice offers a captivating journey that will leave you enlightened and inspired.

As we navigate the complexities of the modern world, it is essential to remember the lessons of the past and continue striving for a fair and just society for all. The National Museum of Justice stands as a powerful testament to the ongoing quest for justice, inviting us all to be active participants in that journey. In doing so, we honour the legacy of those who have fought for justice throughout history and commit ourselves to ensuring that the principles of fairness and equity remain at the forefront of our society. Sitting on that same bench that Emmeline Pankhurst once sat really reminded me of why I initially studied law.

The main thought that I was left with as I left the museum was that justice is not just a concept; it is a lived experience that we all contribute to shaping.

SUPREME COURT VISIT WITH MY CRIMINOLOGY SQUAD!

Author: Dr Paul Famosaya

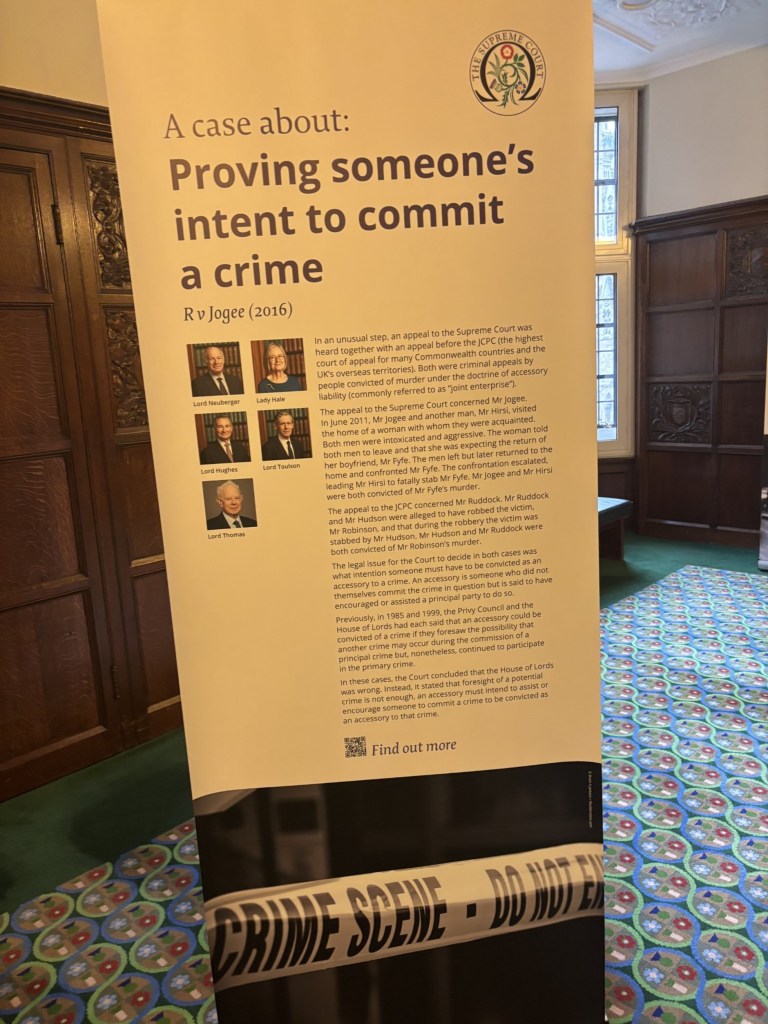

This week, I’m excited to share my recent visit to the Supreme Court in London – a place that never fails to inspire me with its magnificent architecture and rich legal heritage. On Wednesday, I accompanied our final year criminology students along with my colleagues Jes, Liam, and our department head, Manos, on what proved to be a fascinating educational visit. For those unfamiliar with its role, the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom stands at the apex of our legal system. It was established in 2009, and serves as the final court for all civil cases in the UK and criminal cases from England, Wales, and Northern Ireland. From a criminological perspective, this institution is particularly significant as it shapes the interpretation and application of criminal law through precedent-setting judgments that influence every level of our criminal justice system

7:45 AM: Made it to campus just in the nick of time to join the team. Nothing starts a Supreme Court visit quite like a dash through Abington’s morning traffic!

8:00 AM: Our coach is set to whisk us away to London!

Okay, real talk – whoever designed these coach air conditioning systems clearly has a vendetta against warm-blooded academics like me! 🥶 Here I am, all excited about the visit, and the temperature is giving me an impromptu lesson in ‘cry’ogenics. But hey, nothing can hold us down!.

Picture: Inside the coach where you can spot the perfect mix of university life – some students chatting about the visit, while others are already practising their courtroom napping skills 😴

There’s our department Head of Departmen Manos, diligently doing probably his fifth headcount 😂. Big boss is channelling his inner primary school teacher right now, armed with his attendance sheet and pen and all. And yes, there’s someone there in row 5 I think, who’s already dozed off 🤦🏽♀️ Honestly, can’t blame them, it’s criminally early!

9:05 AM The dreaded M1 traffic

Sometimes these slow moments give us the best opportunities to reflect. While we’re crawling through, my mind wanders to some of the landmark cases we’ll be discussing today. The Supreme Court’s role in shaping our most complex moral and legal debates is fascinating – take the assisted dying cases for instance. These aren’t just legal arguments; they’re profound questions about human dignity, autonomy, and the limits of state intervention in deeply personal decisions. It’s also interesting to think about how the evolution of our highest court reflects (or sometimes doesn’t reflect) the society it serves. When we discuss access to justice in our criminology lectures, we often talk about how diverse perspectives and lived experiences shape legal interpretation and decision-making. These thoughts feel particularly relevant as we approach the very institution where these crucial decisions are made.

The traffic might be testing our patience, but at least it’s giving us time to really think about these issues.

10:07 AM – Arriving London – The stark reality of London’s inequality hits you right here, just steps from Hyde Park.

Honestly, this is a scene that perfectly summarises the deep social divisions in our society – luxury cars pulling up to the Dorchester where rooms cost more per night than many people earn in a month, while just meters away, our fellow citizens are forced to make their beds on cold pavements. As a criminologist, these scenes raise critical questions about structural violence and social harms. When we discuss crime and justice in our lectures, we often talk about root causes. Here they are, laid bare on London’s streets – the direct consequences of austerity policies, inadequate mental health support, and a housing crisis that continues to push more people into precarity. But as we say in the Nigerian dictionary of life lessons – WE MOVE!! 🚀

10:31 AM Supreme Court security check time

Security check time, and LISTEN to how they’re checking our students’ water bottles! The way they’re examining those drinks is giving: Nah this looks suspicious 🤔

So there I am, breezing through security like a pro (years of academic conferences finally paying off!). Our students follow suit, all very professional and courtroom-ready. But wait for it… who’s that getting the extra-special security attention? None other than our beloved department head Manos! 😂

The security guard’s face is priceless as he looks through his bags back and forth. Jes whispers to me ‘is Manos trying to sneak in something into the supreme court?’ 😂 Maybe they mistook his collection of snacks for contraband? Or perhaps his stack of risk assessment forms looked suspicious? 😂 There he is, explaining himself, while the rest of us try (and fail) to suppress our giggles. He is a free man after all.

10: 44AM Right so first stop, – Court Room 1.

Our tour guide provided an overview of this institution, established in 2009 when it took over from the House of Lords as the UK’s highest court. The transformation from being part of the legislature to becoming a physically separate supreme court marked a crucial step in the separation of powers in the country’s legislation. There’s something powerful about standing in this room where the Justices (though they usually sit in panels of 5 or 7) make decisions. Each case mentioned had our criminology students leaning in closer, seeing how theoretical concepts from their modules materialise in this very room.

10:59 AM Moving into Court 2, the more modern one!

After exploring Courtroom 1, we moved into Court Room 2, and yep, I also saw the contrast! And apparently, our guide revealed, this is the judges’ favourite spot to dispense justice – can’t blame them, the leather chairs felt lush tbh!

Speaking of judges, give it up for our very own Joseph Buswell who absolutely nailed it when the guide asked about Supreme Court proceedings! 👏🏾 As he correctly pointed out, while we have 12 Supreme Court Justices in total, they don’t all pile in for every case. Instead, they work in panels of 3 or 5 (always keeping it odd to avoid those awkward tie situations). 👏🏾 And what makes Court Room 2 particularly significant for public access to justice the cameras and modern AV equipment which allow for those constitutional and legal debates to be broadcast to the nation. Spot that sneaky camera right at the top? Transparency level: 100% I guess!

The exhibition area

The exhibition space was packed with rich historical moments from the Supreme Court’s journey. Among the displays, I found myself pausing at the wall of Justice portraits. Let’s just say it offered quite the visual commentary on our judiciary’s journey towards representation…

Beyond the portraits, the exhibition showcased crucial stories of landmark judgments that have shaped our legal landscape. Each case display reminded us how crucial diverse perspectives are in the interpretation and application of law in our multicultural society.

11: 21AM Moving into Court 3, home of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC)

The sight of those Commonwealth flags tells a powerful story about the evolution of colonial legal systems and modern voluntary jurisdiction. Our guide explained how the JCPC continues to serve as the highest court of appeal for various independent Commonwealth countries. The relationship between local courts in these jurisdictions and the JCPC raises critical questions about legal sovereignty and judicial independence and the students were particularly intrigued by how different legal systems interact within this framework – with each country maintaining its own laws and legal traditions, yet looks to London for final decisions.

Breaktime!!!!

While the group headed out in search of food, Jes and I were bringing up the rear, catching up after the holiday and literally SCREAMING about last year’s Winter Wonderland burger and hot dog prices (“£7.50 for entry too? In this Keir Starmer economy?!😱”). Anyway, half our students had scattered – some in search of sustenance, others answering the siren call of Zara (because obviously, a Supreme Court visit requires a side of retail therapy 😉).

But here’s the moment that had us STUNNED – right there on the street, who should come power-walking past but Sir Chris Whitty himself! 😱 England’s Chief Medical Officer was on a mission, absolutely zooming past us like he had an urgent SAGE meeting to get to 🏃♂️. That man moves with PURPOSE! I barely had time to nudge Jes before he’d disappeared. One second he was there, the next – gone! Clearly, those years of walking to press briefings during the pandemic have given him some serious speed-walking skills! 👀

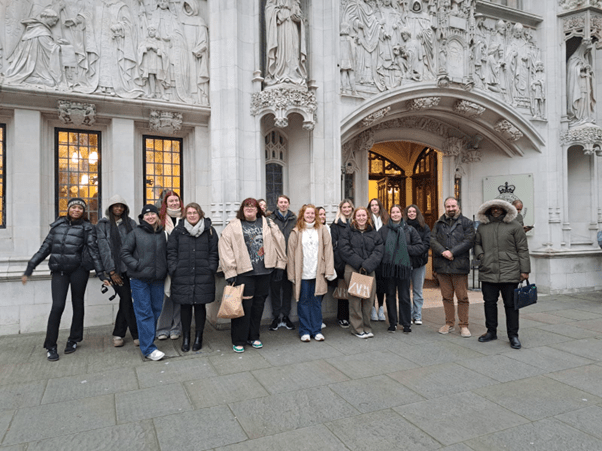

3:30 PM – Group Photo!

Looking at these final year criminology students in our group photo though! Even with that criminal early morning start (pun intended 😅), they made it through the whole Supreme Court experience! Big shout out to all of them 👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾 Can you spot me? I’m the one on the far right looking like I’m ready for Arctic exploration (as Paula mentioned yesterday), not London weather! 🥶 Listen, my ancestral thermometer was not calibrated for this kind cold today o! Had to wrap up in my hoodie like I was jollof rice in banana leaves – and you know we don’t play with our jollof! 😤

4:55 PM Heading Back To NN

On the journey back to NN, while some students dozed off (can’t blame them – legal learning is exhausting!), I found myself reflecting on everything we’d learned. From the workings of the highest court in our land to the stark realities of social inequality we witnessed near Hyde Park, today brought our theoretical classroom discussions into sharp focus. Sitting here, watching London fade into the distance, I’m reminded of why these field trips are so crucial for our students’ understanding of justice, law, and society.

Listen, can we take a moment to appreciate our driver though?! Navigating that M1 traffic like a BOSS, and getting us back safe and sound! The real MVP of the day! 👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾

And just like that, our Supreme Court trip comes to an end. From early morning rush to security check shenanigans, from spotting Chief Medical Officer on the streets to freezing our way through legal history – what a DAY!

To my amazing final years who made this trip extra special – y’all really showed why you’re the future of criminology! 👏🏾 Special shoutout to Manos (who can finally put down his attendance sheet 😂), Jes, and Liam for being the dream team! And to London… boyyyy, next time PLEASE turn up the heat! 🥶

As we all head our separate ways, some students were still chatting about the cases we learned about (while others were already dreaming about their beds 😴), In all, I can’t help but smile – because days like these? This is what university life is all about!

Until our next adventure… your frozen but fulfilled criminology lecturer, signing off! 🙌

Justice or Just Another One?

Luckily I’ve never been one for romantic movies. I always preferred a horror movie. I just didn’t know that my love life would become the worst horror movie I could ever encounter. I was only 18 when I met the monster who presented as a half decent human being. I didn’t know the world very well at that point and he made sure that he became my world. The control and coercion, at the time, seemed like romantic gestures. It’s only with hind sight that I can look back and realise every “kind” and “loving” gesture came from a menacing place of control and selfishness. I was fully under his spell. But anyway, I won’t get into every detail ever. I guess I just wanted to preface this with the fact that abuse doesn’t just start with abuse. It starts with manipulation that is often disguised as love and romance in a twisted way.

This man went on to break me down into a shell of myself before the physical abuse started. Even then, him getting that angry was somehow always my fault. I caused that reaction in his sick, twisted mind and I started to believe it was my fault too. The final incident took place and the last thing I can clearly recall is hearing how he was going to cave my head in before I felt this horrendous pressure on my neck with his other hand keeping me from making any noise that would expose him.

By chance, I managed to get free and RUN to my family. Immediately took photos of my injuries too because even in my state, I know how the Criminal Justice System would not be on my side without evidence they deemed suitable.

Anyway, my case ended up going to trial. Further trauma. Great. I had to relive the entire relationship by having every part of my character questioned on the stand like I was the criminal in this instance. I even got told by his defence that I had “Histrionic Personality Disorder”. Something I have never been diagnosed with, or even been assessed for. Just another way the CJS likes to pathologise women’s trauma. Worst of all, turns out ‘Doctor Defence’ ended up dropping my abuser as he was professionally embarrassed when he realised he knew my mother who was also a witness. Wonderful. This meant I got to go through the process of being criminalised, questioned, diagnosed with disorders I hadn’t heard of at the time, hear the messages, see the photos ALL over again.

Although “justice” prevailed in as much as he was found guilty. All for the sake of a suspended sentence. Perfect. The man who made me feel like he was my world then also tried to end my life was still going to be free enough to see me. The law wasn’t enough to stop him from harming me, why would it be enough to stop him now?

Fortunately for me, it stopped him harming me. However, it did not stop him harming his next victim. For the sake of her, I won’t share any details of her story as it is not mine to share. Yet, this man is now behind bars for a pretty short period of time as he has once again harmed a woman. Evidently, I was right. The law was not enough to stop him. Which leads me to the point of this post, at what stage does the CJS actually start to take women’s pleas to feel safe seriously? Does this man have to go as far to take away a woman’s life entirely before someone finally deems him as dangerous? Why was my harm not enough? Would the CJS have suddenly seen me as a victim, rather than making me feel like a criminal in court, if I was eternally silenced? Why do women have to keep dying at the hands of men because the CJS protects domestic abusers?”

Media Madness

Unless you have been living under a rock or on a remote island with no media access, you would have been made aware of the controversy of Russell Brand and his alleged ‘historic’ problematic behaviour. If we think about Russell Brand in the early 2000s he displayed provocative and eccentric behaviour, which contributed to his rise to fame as a comedian, actor, and television presenter. During this period, he gained popularity for his unique style, which combined sharp wit, a proclivity for wordplay, and a rebellious, countercultural persona.

Brand’s stand-up comedy routines was very much intertwined with his personality, which was littered with controversy, something that was welcomed by the general public and bosses at big media corporations. Hence his never-ending media opportunities, book deals and sell out shows.

In recent years Brand has reinvented (or evolved) himself and his public image which has seen a move towards introspectivity, spirituality and sobriety. Brand has collected millions of followers that praise him for his activist work, he has been vocal on mental health issues, and he encourages his followers to hold government and big corporations to an account.

The media’s cancellation of Russell Brand without any criminal charges being brought against him raises important questions about the boundaries of cancel culture and the presumption of innocence. Brand, a controversial and outspoken comedian, has faced severe backlash for his provocative statements and unconventional views on various topics. While his comments have undoubtedly sparked controversy and debate, the absence of any criminal charges against him highlights the growing trend of public figures being held to account in the court of public opinion, often without a legal basis.

This situation underscores the importance of distinguishing between free speech and harmful behaviour. Cancel culture can sometimes blur these lines, leading to consequences that may seem disproportionate to the alleged transgressions. The case of Russell Brand serves as a reminder of the need for nuanced discussions around cancel culture, ensuring that individuals are held accountable for their actions while also upholding the principle of innocent until proven guilty in a court of law. It raises questions about how society should navigate the complex intersection of free expression, public accountability, and the potential consequences for individuals in the public eye.

There is also an important topic that seems to be forgotten in this web of madness……..what about the alleged victims. There seems to be a theme that continuously needs to be highlighted when criminality and victimisation is presented. There is little discussion or coverage on the alleged victims. The lack of media sensitivity and lay discussion on this topic either dehumanises the alleged victims by using lines such as ‘Brand is another victim of MeToo’ and comparing him to Cliff Richard and Kevin Spacey, two celebrities that were accused of sexual crimes and were later found not guilty, which in essence creates a narrative that does not challenge Brand’s conduct, on the basis of previous cases that have no connection to one another.

We also need to be mindful on the medias framing of the alleged witch hunt against Russell Brand and the problematic involvement that the UK government. The letter penned by Dame Dinenage sent to social media platforms in an attempt to demonetize Brand’s content should also be highlighted. While I support Brand being held accountable for any proven crimes he has committed, I feel these actions by UK government are hasty, and problematic considering there have been many opportunities for the government to step in on serious allegations about media personalities on the BBC and other news stations and they have not chosen to act. The step made by Dame Dinenage has contributed to the media madness and contributes to the out of hand and in many ways, nasty discussion around freedom of speech. The government’s involvement has deflected the importance of the victimisation and criminality. Instead, it has replaced the discussion around the governments overarching punitive control over society.

Brand has become a beacon of understanding to is 6.6 million followers during Covid 19 lockdowns, mask mandates and vaccinations. This was at a time when many people questioned government intentions and challenged the mainstream narratives around autonomy. Because Brand has been propped up as a hero to his ‘awakened’ followers the shift around his conduct and alleged crimes have been erased from conversation and debates around BIG BROTHER and CONTROL continue to shape the media narrative………

When This is Over: Reflections on an Unequal Pandemic

This week a book was released which I both co-edited and contributed to and which has been two years in the making. When This is Over: Reflections on an Unequal Pandemic is a volume combining a range of accounts from artists to poets, practitioners to academics. Our initial aim of the book was borne out of a need for commemoration but we cannot begin to address this without considering inequalities throughout the pandemic.

Each of the four editors had both personal and professional reasons for starting the project. I – like many – was (and still is) deeply affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. When we first went into lockdown, we were shown the data every day, telling us the numbers of people who had the virus and of those who had died with COVID-19. Behind these numbers, I saw each and every person. I thought about their loved ones left behind, how many of them died alone without being able to say goodbye other than through a video screen. I thought about what happened to the bodies afterwards, how death rites would be impacted and how the bereaved would cope without hugs and face to face social support. Then my grandmother died. She had overcome COVID-19 in the way that she was testing negative. But I heard her lungs on the day she died. I know. And so, I became even more consumed with questions of the COVID-19 dead, with/of debates. I was angry at the narratives surrounding the disposability of people’s lives, at people telling me ‘she had a good innings’. It was personal now.

I now understood the impact of not being able to hug my grandpa at my grandmother’s funeral, and how ‘normal’ cultural practices surrounding death were disturbed. My grandmother loved singing in choirs and one of the traumatic parts of our bereavement was not being able to sing at her funeral as she would have wanted and how we wanted to remember her. Lucy Easthope, a disaster planner and one of my co-authors speaks of her frustrations in this regard:

“we’ve done something incredibly traumatising to the families that is potentially bigger than the bereavement itself. In any disaster you should still allow people to see the dead. It is a gross inhumanity of bad planning that people couldn’t’t visit the sick, view the deceased’s bodies, or attend funerals. Had we had a more liberal PPE stockpile we could have done this. PPE is about accessing your loved ones and dead ones, it is not just about medical professionals.”

The book is divided into five parts, each addressing a different theme all of which I argue are relevant to criminologists and each part including personal, professional, and artistic reflections of the themes. Part 1 considered racialised, classed, and gendered identities which impacted on inequality throughout the pandemic, asking if we really are in this together? In this section former children’s laureate Michael Rosen draws from his experience of having COVID-19 and being hospitalised in intensive care for 48 days. He writes about disposability and eugenics-style narratives of herd immunity, highlighting the contrast between such discourse and the way he was treated in the NHS: with great care and like any other patient.

The second part of the book considers how already existing inequalities have been intensified throughout the pandemic in policing, law and immigration. Our very own @paulsquaredd contributed a chapter on the policing of protests during the pandemic, drawing on race in the Black Lives Matter protests and gender in relation to Sarah Everard. As my colleagues and students might expect, I wrote about the treatment of asylum seekers during the initial lockdown periods with a focus on the shift from secure and safe self-contained housing to accommodating people seeking safety in hotels.

Part three considers what happens to the dead in a pandemic and draws heavily on the experiences of crematoria and funerary workers and how they cared for the dead in such difficult circumstances. This part of the book sheds light on some of the forgotten essential workers during the pandemic. During lockdown, we clapped for NHS workers, empathised with supermarket workers and applauded other visible workers but there were many less visible people doing valuable unseen work such as caring for the dead. When it comes to death society often thinks of those who cared for them when they were alive and the bereaved who were left to the exclusion of those who look after the body. The section provides some insight into these experiences.

Moving through the journey of life and death in a pandemic, the fourth section focusses on questions of commemoration, a process which is both personal and political. At the heart of commemorating the COVID-19 dead in the UK is the National COVID Memorial Wall, situated facing parliament and sat below St Thomas’ hospital. In a poignant and political physical space, the unofficial wall cared for by bereaved family members such as Fran Hall recognises and remembers the COVID dead. If you haven’t visited the wall yet, there will be a candlelit vigil walk next Wednesday, 29th March at 7pm and those readers who live further afield can digitally walk the wall here, listening to the stories of bereaved family members as you navigate the 150,837 painted hearts.

The final part of the book both reflects on the mistakes made and looks forward to what comes next. Can we do better in the next pandemic? Emergency planner Matt Hogan presents a critical view on the handling of the pandemic, returning to the refrain, ‘emergency planning is dead. Long live emergency planning’. Lucy Easthope is equally critical, developing what she has discussed in her book When the Dust Settles to consider how and what lessons we can learn from the management of the pandemic. Lucy calls out for activism, concluding with calls to ‘Give them hell’ and ‘to shout a little louder’.

Concluding in his afterword, Gary Younge suggests this is ‘teachable moment’, but will we learn?

When This is Over: Reflections on an Unequal Pandemic is published by Policy Press, an imprint of Bristol University Press. The book can be purchased directly from the publisher who offer a 25% discount when subscribing. It can also be purchased from all good book shops and Amazon.

Public confidence in the CJS: ending on a high?

2022 has been a turbulent and challenging year for many. Social inequalities and disadvantage are rife, with those in power repeatedly making bad, inhumane decisions and with very little, to no, accountability or consequences (insert your favourite example from the sh** storm that is the Conservative Party here). Union after Union, across sectors, engage in industrial action in response to poor working conditions and pay, amidst a cost-of-living crisis. And although seemingly unconnected, as the year comes to a close, the Sentencing Guidelines (2022) report on Public Confidence in the Criminal Justice System (CJS) has got me feeling frustrated. My previous blog entries have often been ‘moans’. And whilst January is often dubbed the month of new beginnings and change for the year ahead: we’re not quite there yet so true to form here is my latest moan!

The report exists as one of many conducted by Savanta to collate data on public confidence, in terms of effectiveness and fairness, in the CJS and public awareness of the sentencing guidelines. The data collected in March 2022, was via online surveys given to a “nationally representative sample of 2,165 adults in England and Wales” (Archer et al., 2022, p.9). Some of their highlighted ‘Key Findings’ include that confidence levels in CJS remains relatively stable in comparison to 2018, on the whole, respondents viewed sentences as ‘too lenient’ however this varied based on offence, the existence of the sentencing guidelines improves respondent’s confidence in the fairness of sentencing, and that engagement with broadcast news sources was high across respondents (Archer et al., 2022). It is not the findings, per se, that I take umbrage with, but rather the claim it is a “nationally representative sample of adults in England and Wales” (Archer et al., 2022, p.9).

I take issue on two fronts. The first being that the sample size of 2,165 adult respondents is representative when the demographic factors included are: gender (male and female), age (18-34yo, 35-54yo and 55+), region, ethnicity (White, Mixed, Asian, Black and Other) and socio-economic grade. Now considering we are, thankfully, at the end of 2022 we should all be able to recognise that a sample which only includes cis-gendered options, narrows ethnicity down to 4 categories and the charming ‘other’, and does not include disabilities is problematic. There has been a large body of research done on people with disabilities and their experiences within the CJS, the lack of representation, the lack of accessibility to space and decisions, potentially impacting a defendant’s right to a fair trial, and a victim’s right to justice (Equality and Human Rights Commission, 2021; Hyun et al., 2013 ). So I ask, is this not something which needs considering when looking at public confidence in the CJS of a “nationally representative” sample?

In addition to this, I take issue with the requirement that the sample be “nationally representative”. We have research piece upon research piece about how Black men and Black boys experience the CJS and its various agencies disproportionately to their white counterparts (Lammy, 2017; Monteith et al., 2022; Parmar, 2012). Their experiences of stop and search, sentencing, bail, access to programmes within the Secure and Youth estate. There is nothing representative about our CJS in terms of who it processes, how this is done, and by whom. According to Monteith et al., (2022) 1% of Judges in the CJS are Black, and there are NO Black judges on the High Court, Court of Appeal of Supreme Court: this is not representative! Why then, are we concerned with a representative sample when looking at public confidence in CJS and the sentencing guidelines, when it is not experienced in a proportionate manner?

Maybe I’ve missed the point?

The report is clear, accessible, visible to the public: crucial concepts when thinking about justice, and measuring public confidence in the CJS is fraught with difficulties (Bradford and Myhill, 2015; Kautt and Tankebe, 2011). But this just feels like another nail being thumped into the coffin that is 2022. Might be the eagerness I possess to leave 2022 behind, or the impeding dread for the year to follow but the report has angered me rather than reassured me. As a criminologist, I am hopeful for a more inclusive, representative, fair and accountable CJS, but I am not sure how this will be achieved if we do not accept that the system disproportionately impacts (but not exclusively) Black men, women and children. Think it might be time for another mince pie…

Happy New Year to you all!

References:

Archer, N., Butler, M., Avukatu, G. and Williams, E. (2022) Public Knowledge of Confidence in the Criminal Justice System and Sentencing: 2022 Research. London: Sentencing Council.

Bradford, B. and Myhill, A. (2015) Triggers of change to public confidence in the police and criminal justice system: Findings from the crime survey for England and Wales panel experiment, Criminology and Criminal Justice, 15(1), pp.23-43.

Equality and Human Rights Commission (2021) Does the criminal justice system treat disabled people fairly? [Online] Available at: https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/en/inquiries-and-investigations/does-criminal-justice-system-treat-disabled-people-fairly [ Accessed 4th November 2021].

Hyun, E., Hahn, L. and McConnell, D. (2013) Experiences of people with learning disabilities in the criminal justice system, British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 42: 308-314.

Kautt, P. and Tankebe, J. (2011) Confidence in the Criminal Justice System in England and Wales: A Test of Ethnic Effects, International Criminal Justice Review, 21(2),pp. 93-117.

The Lammy Review (2017) The Lammy Review: An independent review into the treatment of, and outcomes for, Black Asian and Minority Ethnic Individuals in the Criminal Justice System, [online] Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/goverment/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/643001/lammy-review-final-report-pdf [Last Accessed 14th February 2021].

Monteith, K., Quinn, E., Dennis, A., Joseph-Sailsbury, R., Kane, E., Addo, F. and McGourlay, C. (2022) Racial Bias and the Bench: A Response to the Judicial Diversity and Inclusion Strategy (2020-2025), [online] Available at: https://documents.manchester.ac.uk/display.aspax?DOCID=64125 [Accessed 4th November 2022].

Parmar, A. (2012) Racism and ethnicity in the criminal justice process, in: Hucklesby, A. and Wahidin, A. (eds.) Criminal Justice, 2nd ed, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp.267-296.