Home » Knowledge

Category Archives: Knowledge

25 years is but a drop in time!

If I was a Roman, I would be sitting in my comfortable triclinium eating sweet grapes and dictating my thoughts to a scribe. It was the Roman custom of celebrating a double-faced god that started European celebrations for a new year. It was meant to be a time of reflection, contemplation and future resolutions. It is under these sentiments that I shall be looking back over the year to make my final calculations. Luckily, I am not Roman, but I am mindful that over 2025 years have passed and many people, have tried to look back. Since I am not any of these people, I am going to look into the future instead.

In 25 years from now we shall be heading to the middle of the 21st century. A century that comes with great challenges. Since the start of the century there has been talk of economic bust. The banking crisis slowed down the economy and decreased real income for people. Then the expectation was that crime will rise as it did before; whilst the juries may still be out. the consensus is that this crime spree did not come…at least not as expected. People became angry and their anger was translated in changes on the political map, as many countries moved to the right.

Prediction 1: This political shift to the right in the next 25 years will intensify and increase the polarisation. As politics thrives in opposition, a new left will emerge to challenge the populist right. Their perspective will bring another focus on previous divisions such as class. Only on this occasion class could take a different perspective. The importance of this clash will define the second half of the 21st century when people will try to recalibrate human rights across the planet. Globalisation has brought unspeakable wealth to few people. The globalisation of citizenship will challenge this wealth and make demands on future gains.

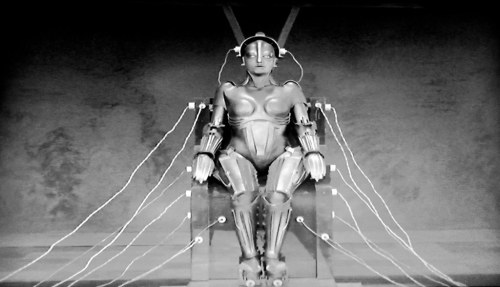

As I write these notes my laptop is trying to predict what I will say and put a couple of words ahead of me. Unfortunately, most times I do not go with its suggestions. As I humanise my device, I feel sorry for its inability to offer me the right words and sometimes I use the word as to acknowledge its help but afterwards I delete it. My relationship with technology is arguably limited but I do wonder what will happen in 25 years from now. We have been talking about using AI for medical research, vaccines, space industry and even the environment. However currently the biggest concern is not AI research, but AI generated indecent images!

Prediction 2: Ai is becoming a platform that we hope will expand human knowledge at levels that we could have not previously anticipated. One of its limitations comes from us. Our biology cannot receive the volume of information created and there is no current interface that can sustain it. This ultimately will lead to a divide between people. Those who will be in favour of incorporating more technology into their lives and those who will ultimately reject it. The polarisation of politics could contribute to this divide as well. As AI will become more personal and intrusive the more the calls will be made to regulate. Under the current framework to fully regulate it seems rather impossible so it will lead to an outright rejection or a complete embrace. We have seen similar divides in the past during modernity; so, this is not a novel divide. What will make it more challenging now is the control it can hold into everyday life. It is difficult to predict what will be the long-term effects of this.

During the late 20th and early 21st centuries drug abuse and trafficking seemed to continue to scandalise the public and maintain attention as much as it did back in the 1970s and 80s. Drugs have been demonised and became the topic of media representation of countless moral panics. Its reach in the public is wide and its emotional effect rivals only that of child abuse. Is drugs abuse an issue we shall be considering in 25 years from now?

Prediction 3: People used substances as far back as we can record history. Therefore, there will be drugs in the future to the joy of all these people who like to get high! It is most likely that the focus will be on synthetic drugs that will be more focused on their effects and how they impact people. The production is likely to change with printers being able to develop new substances on a massive scale. These will create a new supply line among those who own technology to develop new synthetic forms and those who own the networks of supply. In previous times a takeover did happen so it is likely to happen again, unless these new drugs emerge under formal monopolies, like drug companies who will legalise their recreative use.

One of the biggest tensions in recent years is the possibility of another war. Several European politicians have already raised it pretending to be making predictions. Their statements however are clear signs of war preparation. The language is reminiscent of previous eras and the way society is responding to these seems that there is some fertile ground. Nationalism is the shelter of every failed politician who promises the world and delivers nothing. Whether a citizen in Europe (EU/UK) the US or elsewhere, they have likely to have been subjected to promises of gaining things, better days coming, making things great…. only to discover all these were empty vacant words. Nothing has been offered and, in most cases, working people have found that their real incomes have shrunk. This is when a charlatan will use nationalism to push people into hating other people as the solution to their problems.

Prediction 4: Unfortunately, wars seem to happen regularly in human history despite their destructive nature. We also forget that war has never stopped and elusive peace happens only in parts of the world when different interests converge. There is a combination of patriotism, national pride and rhetoric that makes people overlook how damaging war is. It is awfully blindsided not to recognise the harm war can do to them and to their own families. War is awful and destroys working people the most. In the 20th century nuclear armament led to peace hanging by a thread. This fear stupidly is being played down by fraudsters pretending to be politicians. Currently the talk about hybrid war or proxy war are used to sanitise current conflicts. The use of drones seems to have altered the methodology of war, and the big question for the next 25 years is, will there be someone who will press THAT button? I am not sure if that will be necessary because irrespective of the method, war leaves deep wounds behind.

In recent years the discussion about the weather have brought a more prevailing question. What about the environment? There is a recognised crisis that globally we seem unable to tackle, and many make already quite bleak predictions about it. Decades ago, Habermas was exploring the idea of “colonization of the lifeworld” purporting that systemic industrial agriculture will lead to environmental degradation. Now it seems that this form of farming, the greenhouse gasses and deforestation are becoming the contributing factors of global warming. The inaction or the lack of international coordination has led calls for immediate action. Groups that have been formed to pressure political indecision have been met with resistance and suspicion, but ultimately the problem remains.

Prediction 5: The world acts when confronted with something eminent. In the future some catastrophic events are likely to shape views and change attitudes. Unfortunately, the planet runs on celestial and not human time. When a prospective major event happens, no one can predict its extent or its impact. The approach by some super-rich to travel to another planet or develop something in space is merely laughable but it is also a clear demonstration why wealth cannot be in the hands of few oligarchs. Life existed before them and hopefully it will continue well beyond them. On the environment I am hopeful that people’s views will change so by the end of this century we will look at the practices of people like me and despair.

These are mere predictions of someone who sits in a chair having read the news of the day. They carry no weight and hold no substantive strength. There is a recognition that things will change at some level and we shall be asked to adapt to whatever new conditions we are faced with. In 25 years from now we will still be asking similar questions people asked 100 years ago. Whatever happens, however it happens, life always finds a way to continue.

25 years has gone too fast…

When we began, criminology was a single programme, a bold idea with big ambitions. Over the years, that idea grew into a department, and today, into a vibrant academic community offering a diverse range of courses that reflect the complexity of justice and society.

Our commitment to innovation has shaped this journey. We introduced research placements, immersive trips, and fieldwork experiences, from the Museum of Justice in the early days to visits to the Supreme Court more recently. These experiences have given our students not just knowledge, but perspective connecting theory with practice in powerful ways.

We’ve developed a wide range of modules and resources for those who wish to study criminology, equipping them with the skills and knowledge to join the wider criminology family. Our aim has always been to prepare students for both professional careers and academic study, ensuring they can explore every facet of this dynamic discipline.

None of this would have been possible without colleagues who share a passion for teaching and learning. Together, we’ve engaged students with new ways of thinking and approaches—turning them into the colleagues of tomorrow. This is the heart of what we do: inspiring, challenging, and empowering future generations.

As we celebrate this milestone, we also look forward. Criminology is ever evolving, and so are we. Our commitment to innovation, inclusivity, and excellence remains as strong as ever. The next 25 years will bring new challenges and opportunities and I know we will meet them with the same passion and purpose that brought us here today.

Thank you to everyone colleagues, students, partners who has been part of this incredible journey. Here’s to the next chapter in advancing criminology education and research. Together, we will continue to make a difference.

Technology: one step forward and two steps back

I read my colleague @paulaabowles’s blog last week with amusement. Whilst the blog focussed on AI and notions of human efficiency, it resonated with me on so many different levels. Nightmarish memories of the three E’s (economy, effectiveness and efficiency) under the banner of New Public Management (NPM) from the latter end of the last century came flooding back, juxtaposed with the introduction of so-called time saving technology from around the same time. It seems we are destined to relive the same problems and issues time and time again both in our private and personal lives, although the two seem to increasingly morph into one, as technology companies come up with new ways of integration and seamless working and organisations continuously strive to become more efficient with little regard to the human cost.

Paula’s point though was about being human and what that means in a learning environment and elsewhere when technology encroaches on how we do things and more importantly why we do them. I, like a number of like-minded people are frustrated by the need to rush into using the new shiny technology with little consideration of the consequences. Let me share a few examples, drawn from observation and experience, to illustrate what I mean.

I went into a well-known coffee shop the other day; in fact, I go into the coffee shop quite often. I ordered my usual coffee and my wife’s coffee, a black Americano, three quarters full. Perhaps a little pedantic or odd but the three quarters full makes the Americano a little stronger and has the added advantage of avoiding spillage (usually by me as I carry the tray). Served by one of the staff, I listened in bemusement as she had a conversation with a colleague and spoke to a customer in the drive through on her headset, all whilst taking my order. Three conversations at once. One full, not three quarters full, black Americano later coupled with ‘a what else was it you ordered’, tended to suggest that my order was not given the full concentration it deserved. So, whilst speaking to three people at once might seem efficient, it turns out not to be. It might save on staff, and it might save money, but it makes for poor service. I’m not blaming the young lady that served me, after all, she has no choice in how technology is used. I do feel sorry for her as she must have a very jumbled head at the end of the day.

On the same day, I got on a bus and attempted to pay the fare with my phone. It is supposed to be easy, but no, I held up the queue for some minutes getting increasingly frustrated with a phone that kept freezing. The bus driver said lots of people were having trouble, something to do with the heat. But to be honest, my experience of tap and go, is tap and tap and tap again as various bits of technology fail to work. The phone won’t open, it won’t recognise my fingerprint, it won’t talk to the reader, the reader won’t talk to it. The only talking is me cursing the damn thing. The return journey was a lot easier, the bus driver let everyone on without payment because his machine had stopped working. Wasn’t cash so much easier?

I remember the introduction of computers (PCs) into the office environment. It was supposed to make everything easier, make everyone more efficient. All it seemed to do was tie everyone to the desk and result in redundancies as the professionals, took over the administrative tasks. After all, why have a typing pool when everyone can type their own reports and letters (letters were replaced by endless, meaningless far from efficient, emails). Efficient, well not really when you consider how much money a professional person is being paid to spend a significant part of their time doing administrative tasks. Effective, no, I’m not spending the time I should be on the role I was employed to do. Economic, well on paper, fewer wages and a balance sheet provided by external consultants that show savings. New technology, different era, different organisations but the same experiences are repeated everywhere. In my old job, they set up a bureaucracy task force to solve the problem of too much time spent on administrative tasks, but rather than look at technology, the task force suggested more technology. Technology to solve a technologically induced problem, bonkers.

But most concerning is not how technology fails us quite often, nor how it is less efficient than it was promised to be, but how it is shaping our ability to recall things, to do the mundane but important things and how it stunts our ability to learn, how it impacts on us being human. We should be concerned that technology provides the answers to many questions, not always the right answers mind you, but in doing so it takes away our ability to enquire, critique and reason as we simply take the easy route to a ready-made solution. I can ask AI to provide me with a story, and it will make one up for me, but where is the human element? Where is my imagination, where do I draw on my experiences and my emotions? In fact, why do I exist? I wonder whether in human endeavour, as we allow technology to encroach into our lives more and more, we are not actually progressing at all as humans, but rather going backwards both emotionally and intellectually. Won’t be long now before some android somewhere asks the question, why do humans exist?

How to make a more efficient academic

Against a backdrop of successive governments’ ideology of austerity, the increasing availability of generative Artificial Intelligence [AI] has made ‘efficiency’ the top of institutional to-do-lists’. But what does efficiency and its synonym, inefficiency look like? Who decides what is efficient and inefficient? As always a dictionary is a good place to start, and google promptly advises me on the definition, along with some examples of usage.

The definition is relatively straightforward, but note it states ‘minimum wasted effort of expense’, not no waste at all. Nonetheless the dictionary does not tell us how efficiency should be measured or who should do that measuring. Neither does it tell us what full efficiency might look like, given the dictionary’s acknowledgement that there will still be time or resources wasted. Let’s explore further….

When I was a child, feeling bored, my lovely nan used to remind me of the story of James Watt and the boiling kettle and that of Robert the Bruce and the spider. The first to remind me that being bored is just a state of mind, use the time to look around and pay attention. I wouldn’t be able to design the steam engine (that invention predated me by some centuries!) but who knows what I might learn or think about. After all many millions of kettles had boiled and he was the only one (supposedly) to use that knowledge to improve the Newcomen engine. The second apocryphal tale retold by my nan, was to stress the importance of perseverance as essential for achievement. This, accompanied by the well-worn proverb, that like Bruce’s spider, if at first you don’t succeed, try, try again. But what does this nostalgic detour have to do with efficiency? I will argue, plenty!

Whilst it may be possible to make many tasks more efficient, just imagine what life would be like without the washing machine, the car, the aeroplane, these things are dependent on many factors. For instance, without the ready availability of washing powder, petrol/electricity, airports etc, none of these inventions would survive. And don’t forget the role of people who manufacture, service and maintain these machines which have made our lives much more efficient. Nevertheless, humans have a great capacity for forgetting the impact of these efficiencies, can you imagine how much labour is involved in hand-washing for a family, in walking or horse-riding to the next village or town, or how limited our views would be without access (for some) to the world. We also forget that somebody was responsible for these inventions, beyond providing us with an answer to a quiz question. But someone, or groups of people, had the capacity to first observe a problem, before moving onto solving that problem. This is not just about scientists and engineers, predominantly male, so why would they care about women’s labour at the washtub and mangle?

This raises some interesting questions around the 20th century growth and availability of household appliances, for example, washing machines, tumble driers, hoovers, electric irons and ovens, pressure cookers and crock pots, the list goes on and on. There is no doubt, with these appliances, that women’s labour has been markedly reduced, both temporally and physically and has increased efficiency in the home. But for whose benefit? Has this provided women with more leisure time or is it so that their labour can be harnessed elsewhere? Research would suggest that women are busier than ever, trying to balance paid work, with childcare, with housekeeping etc. So we can we really say that women are more efficient in the 21st century than in previous centuries, it seems not. All that has really happened is that the work they do has changed and in many ways, is less visible.

So what about the growth in technology, not least, generative AI? Am I to believe, as I was told by Tomorrow’s World when growing up, that computers would improve human lives immensely heralding the advent of the ‘leisure age’? Does the increase in generative AI such as ChatGPT, mark a point where most work is made efficient? Unfortunately, I’ve yet to see any sign of the ‘leisure age’, suggesting that technology (including AI) may add different work, rather than create space for humans to focus on something more important.

I have academic colleagues across the world, who think AI is the answer to improving their personal, as well as institutional, efficiency. “Just imagine”, they cry, “you can get it to write your emails, mark student assessment, undertake the boring parts of research that you don’t like doing etc etc”. My question to them is, “what’s the point of you or me or academia?”.

If academic life is easily reducible to a series of tasks which a machine can do, then universities and academics have been living and selling a lie. If education is simply feeding words into a machine and copying that output into essays, articles and books, we don’t need academics, probably another machine will do the trick. If we’re happy for AI to read that output to video, who needs classrooms and who needs lecturers? This efficiency could also be harnessed by students (something my colleagues are not so keen on) to write their assessments, which AI could then mark very swiftly.

All of the above sounds extremely efficient, learning/teaching can be done within seconds. Nobody need read or write anything ever again, after all what is the point of knowledge when you’ve got AI everywhere you look…Of course, that relies on a particularly narrow understanding which reduces knowledge to meaning that which is already known….It also presupposes that everyone will have access to technology at all times in all places, which we know is fundamentally untrue.

So, whatever will we do with all this free time? Will we simply sit back, relax and let technology do all the work? If so, how will humans earn money to pay the cost of simply existing, food/housing/sanitation etc? Will unemployment become a desirable state of being, rather than the subject of long-standing opprobrium? If leisure becomes the default, will this provide greater space for learning, creating, developing, discovering etc. or will technology, fueled by capitalism, condemn us all to mindless consumerism for eternity?

Criminology in the neo-liberal milieu

I do not know whether the title is right nor whether it fits what I want to say, but it is sort of catchy, well I think so anyway even if you don’t. I could never have imagined being capable of thinking up such a title let alone using words such as ‘milieu’ before higher education. I entered higher education halfway through a policing career. I say entered; it was more of a stumble into. A career advisor had suggested I might want to do a management diploma to advance my career, but I was offered a different opportunity, a taster module at a ‘new’ university. I was fortunate, I was to renew an acquaintance with Alan Marlow previously a high-ranking officer in the police and now a senior lecturer at the university. Alan, later to become an associate professor and Professor John Pitts became my mentors and I never looked back, managing to obtain a first-class degree and later a PhD. I will be forever grateful to them for their guidance and friendship. I had found my feet in the vast criminology ocean. However, what at first was delight in my achievements was soon to be my Achilles heel.

Whilst policing likes people with knowledge and skills, some of the knowledge and skills butt up against the requirements of the role. Policing is functional, it serves the criminal justice system, such as it, and above all else it serves its political masters. Criminology however serves no master. As criminologists we are allowed to shine our spotlight on what we want, when we want. Being a police officer tends to put a bit of a dampener on that and required some difficult negotiating of choppy waters. It felt like I was free in a vast sea but restrained with a life ring stuck around my arms and torso with a line attached so as to never stray too far from the policing ideology and agenda. But when retirement came, so too came freedom.

By design or good luck, I landed myself a job at another university, the University of Northampton. I was interviewed for the job by Dr @manosdaskalou., along with Dr @paulaabowles (she wasn’t Dr then but still had a lot to say, as criminologists do), became my mentors and good friends. I had gone from one organisation to another. If I thought I knew a lot about criminology when I started, then I was wrong. I was now in the vast sea without a life ring, freedom was great but quite daunting. All the certainties I had were gone, nothing is certain. Theories are just that, theories to be proved, disproved, discarded and resurrected. As my knowledge widened and I began to explore the depths of criminology, I realised there was no discernible bottom to knowledge. There was only one certainty, I would never know enough and discussions with my colleagues in criminology kept reminding me that was the case.

Why the ‘neo-liberal milieu’ you might ask, after all this seems to be a romanticised story about a seemingly successful transition from one career to another. Well, here’s the rub of it, universities are no different to policing, both are driven, at an arm’s length, by neo liberal ideologies. The business is different but subjugation of professional ideals to managerialist ideology is the same. Budgets are the bottom line; the core business is conducted within considerable financial constraints. The front-line staff take the brunt of the work; where cuts are made and processes realigned, it is the front-line staff that soak up the overflow. Neo-Taylorism abounds, as spreadsheets to measure human endeavour spring up to aide managers both in convincing themselves, and their staff, that more work is possible in and even outside, the permitted hours. And to maintain control, there is always, the age-old trick of re-organisation. Keep staff on their toes and in their place, particularly professionals.

The beauty of being an academic, unlike a police officer, is that I can have an opinion and at least for now I’m able to voice it. But such freedoms are under constant threat in a neo-liberal setting that seems to be seeping into every walk of life. And to be frank and not very academic, it sucks!

By whose standards?

This blog post takes inspiration from the recent work of Jason Warr, titled ‘Whitening Black Men: Narrative Labour and the Scriptural Economics of Risk and Rehabilitation,’ published in September 2023. In this article, Warr sheds light on the experiences of young Black men incarcerated in prisons and their navigation through the criminal justice system’s agencies. He makes a compelling argument that the evaluation and judgment of these young Black individuals are filtered through a lens of “Whiteness,” and an unfair system that perceives Black ideations as somewhat negative.

In his careful analysis, Warr contends that Black men in prisons are expected to conform to rules and norms that he characterises as representing a ‘White space.’ This expectation of adherence to predominantly White cultural standards not only impacts the effectiveness of rehabilitation programmes but also fails to consider the distinct cultural nuances of Blackness. With eloquence, Warr (2023, p. 1094) reminds us that ‘there is an inherent ‘whiteness’ in behavioural expectations interwoven with conceptions of rehabilitation built into ‘treatment programmes’ delivered in prisons in the West’.

Of course, the expectation of adhering to predominantly White cultural norms transcends the prison system and permeates numerous other societal institutions. I recall a former colleague who conducted doctoral research in social care, asserting that Black parents are often expected to raise and discipline their children through a ‘White’ lens that fails to resonate with their lived experiences. Similarly, in the realm of music, prior to the mainstream acceptance of hip-hop, Black rappers frequently voiced their struggles for recognition and validation within the industry due similar reasons. This phenomenon extends to award ceremonies for Black actors and entertainers as well. In fact, the enduring attainment gap among Black students is a manifestation of this issue, where some students find themselves unfairly judged for not innately meeting standards set by a select few individuals. Consequently, the significant contributions of Black communities across various domains – including fashion, science and technology, workplaces, education, arts, etc – are sometimes dismissed as substandard or lacking in quality.

The standards I’m questioning in this blog are not solely those shaped by a ‘White’ cultural lens but also those determined by small groups within society. Across various spheres of life, whether in broader society or professional settings, we frequently encounter phrases like “industry best practices,” “societal norms,” or “professional standards” used to dictate how things should be done.

However, it’s crucial to pause and ask:

By whose standards are these determined?

And are they truly representative of the most inclusive and equitable practices?

This is not to say we should discard all concepts of cultural traditions or ‘best practices’. But we need to critically examine the forces that establish standards that we are sometimes forced to follow. Not only do we need to examine them, we must also be willing to evolve them when necessary to be more equitable and inclusive of our full societal diversity.

Minority groups (by minority groups here, I include minorities in race, class, and gender) face unreasonably high barriers to success and recognition – where standards are determined only by a small group – inevitably representing their own identity, beliefs and values.

So in my opinion, rather than defaulting to de facto norms and standards set by a privileged few, we should proactively construct standards that blend the best wisdom from all groups and uplift underrepresented voices – and I mean standards that truly work for everyone.

References

Warr, J. (2023). Whitening Black Men: Narrative Labour and the Scriptural Economics of Risk and Rehabilitation, The British Journal of Criminology, Volume 63, Issue 5, Pages 1091–1107, https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azac066