Home » Justice (Page 6)

Category Archives: Justice

CRCs: Did we really expect them to work?

For those of you who follow changes in the Criminal Justice System (CJS) or have studied Crime and Justice, you will be aware that current probation arrangements are based on the notion of contestability, made possible by the Offender Management Act 2007 and fully enacted under the Offender Rehabilitation Act 2014. What this meant in practice was the auctioning off of probation work to newly formed Community Rehabilitation Companies (CRCs) in 2015 (Davies et al, 2015). This move was highly controversial and was strongly opposed by practitioners and academics alike who were concerned that such arrangements would undermine the CJS, result in a deskilled probation service, and create a postcode lottery of provision (Raynor et al., 2014; Robinson et al., 2016). The government’s decision to ignore those who may be considered experts in the field has had perilous consequences for those receiving the services as well as the service providers themselves.

Picking up on @manosdaskalou’s theme of justice from his June blog and considering the questions overhanging the future sustainability of the CRC arrangements it is timely to consider these provisions in a little more detail. In recent weeks I have found myself sitting on a number of probation or non-CPS courts where I have witnessed first-hand the inadequacies of the CRC arrangements and potential injustices faced by offenders under their supervision. For instance, I have observed a steady increase in applications from probation, or more specifically CRCs, to have community orders adjusted. While such requests are not in themselves unusual, the type of adjustment or more specifically the reason behind the request, are. For example, I have witnessed an increase in requests for the Building Better Relationships (BBR) programme to be removed because there is insufficient time left on the order to complete it, or that the order itself is increased in length to allow the programme to be completed[1]. Such a request raises several questions, firstly why has an offender who is engaged with the Community Order not been able to complete the BBR within a 12-month, or even 24-month timeframe? Secondly, as such programmes are designed to reduce the risk of future domestic abuse, how is rehabilitation going to be achieved if the programme is removed? Thirdly, is it in the interests of justice or fairness to increase the length of the community order by 3 to 6 month to allow the programme to be complete? These are complex questions and have no easy answer, especially if the reason for failing to complete (or start) the programme is not the offenders fault but rather the CRCs lack of management or organisation. Where an application to increase the order is granted by the court the offender faces an injustice in as much as their sentencing is being increased, not based on the severity of the crime or their failure to comply, but because the provider has failed to manage the order efficiently. Equally, where the removal of the BBR programme is granted it is the offender who suffers because the rehabilitative element is removed, making punishment the sole purpose of the order and thus undermining the very reason for the reform in the first place.

Whilst it may appear that I am blaming the CRCs for these failings, that is not my intent. The problems are with the reform itself, not necessarily the CRCs given the contracts. Many of the CRCs awarded contracts were not fully aware of the extent of the workload or pressure that would come with such provisions, which in turn has had a knock-on effect on resources, funding, training, staff morale and so forth. As many of these problems were also those plaguing probation post-reform, it should come as little surprise that the CRCs were in no better a position than probation, to manage the number of offenders involved, or the financial and resource burden that came with it.

My observations are further supported by the growing number of news reports criticising the arrangements, with headlines like ‘Private probation firms criticised for supervising offenders by phone’ (Travis, 2017a), ‘Private probation firms fail to cut rates of reoffending’ (Savage, 2018), ‘Private probation firms face huge losses despite £342m ‘bailout’’ (Travis, 2018), and ‘Private companies could pull out of probation contracts over costs’ (Travis, 2017b). Such reports come as little surprise if you consider the strength of opposition to the reform in the first place and their justifications for it. Reading such reports leaves me rolling my eyes and saying ‘well, what did you expect if you ignore the advice of experts!’, such an outcome was inevitable.

In response to these concerns, the Justice Committee has launched an inquiry into the Government’s Transforming Rehabilitation Programme to look at CRC contracts, amongst other things. Whatever the outcome, the cost of additional reform to the tax payer is likely to be significant, not to mention the impact this will have on the CJS, the NPS, and offenders. All of this begs the question of what the real intention of the Transforming Rehabilitation reform was, that is who was it designed for? If it’s aim was to reduce reoffending rates by providing support to offenders who previously were not eligible for probation support, then the success of this is highly questionable. While it could be argued that more offenders now received support, the nature and quality of the support is debatable. Alternatively, if the aim was to reduce spending on the CJS, the problems encountered by the CRCs and the need for an MoJ ‘bail out’ suggests that this too has been unsuccessful. In short, all that we can say about this reform is that Chris Grayling (the then Home Secretary), and the Conservative Government more generally have left their mark on the CJS.

[1] Community Orders typically lasts for 12 months but can run for 24 months. The BBR programme runs over a number of weeks and is often used for cases involving domestic abuse.

References:

Davies, M. (2015) Davies, Croall and Tyrer’s Criminal Justice. Harlow: Pearson.

Raynor, P., Ugwudike, P. and Vanstone, M. (2014) The impact of skills in probation work: A reconviction study. Criminology and Criminal Justice, 14(2), pp.235–249.

Robinson, G., Burke, L., and Millings, M. (2016) Criminal Justice Identities in Transition: The Case of Devolved Probation Services in England and Wales. British Journal of Criminology, 56(1), pp.161-178.

Savage, M. (2018) Private probation firms fail to cut rates of reoffending. Guardian [online]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2018/feb/03/private-firms-fail-cut-rates-reoffending-low-medium-risk-offenders [Accessed 6 July 2018].

Travis, A. (2017a) Private probation firms criticised for supervising offenders by phone. Guardian [online]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2017/dec/14/private-probation-firms-criticised-supervising-offenders-phone [Accessed 6 July 2018].

Travis, A. (2017b) Private companies could pull out of probation contracts over costs. Guardian [online]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2017/mar/21/private-companies-could-pull-out-of-probation-contracts-over-costs [Accessed 6 July 2018].

Travis, A. (2018) Private probation firms face huge losses despite £342m ‘bailout’. Guardian [online]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2018/jan/17/private-probation-companies-face-huge-losses-despite-342m-bailout [Accessed 6 July 2018].

The never-changing face of justice

There are occasions that I consider more fundamental questions beyond criminology, such as the nature of justice. Usually whilst reading some new sentencing guidelines or new procedures but on occasions major events such as the fire at Grenfell and the ensuing calls from former residents for accountability and of course justice! There are good reasons why contemplating the nature of justice is so important in any society especially one that has recently embarked on a constitutional discussion following the Brexit referendum.

Justice is perhaps one of the most interesting concepts in criminology; both intangible and tangible at the same time. In every day discourses we talk about the Criminal Justice System as a very precise order of organisations recognising its systemic nature or as a clear journey of events acknowledging its procedural progression. Both usually are summed up on the question I pose to students; is justice a system or a process? Of course, those who have considered this question know only too well that justice is both at different times. As a system, justice provides all those elements that make it tangible to us; a great bureaucracy that serves the delivery of justice, a network of professions (many of which are staffed by our graduates) and a structure that (seemingly) provides us all with a firm sense of equity. As a process, we identify each stage of justice as an autonomous entity, unmolested by bias, thus ensuring that all citizens are judged on the same scales. After all, lady justice is blind but fair!

This is our justice system since 1066 when the Normans brought the system we recognise today and even when, despite uprisings and revolutions such as the one that led to the 1215 signing of the Magna Carta, many facets of the system have remained quite the same. An obvious deduction from this is that the nature of justice requires stability and precedent in order to function. Tradition seems to captivate people; we only need a short journey to the local magistrates’ court to see centuries old traditions unfold. I imagine that for any time traveler, the court is probably the safest place to be, as little will seem to them to be out of place.

So far, we have been talking about justice as a tangible entity as used by professionals daily. What about the other side of justice? The intangible concept on fairness, equal opportunity and impartiality? This part is rather contentious and problematic. This is the part that people call upon when they say justice for Grenfell, justice for Stephen Lawrence, justice for Hillsborough. The people do not simply want a mechanism nor a process, but they want the reassurance that justice is not a privilege but a cornerstone of civic life. The irony here; is that the call for justice, among the people who formed popular campaigns that either led or will lead to inquiries often expose the inadequacies, failings and injustices that exist(ed) in our archaic system.

These campaigns, have made obvious something incredibly important, that justice should not simply appear to be fair, but it must be fair and most importantly, has to learn and coincide with the times. So lady justice may be blind, but she may need to come down and converse with the people that she seeks to serve, because without them she will become a fata morgana,a vision that will not satisfy its ideals nor its implementation. Then justice becomes another word devoid of meaning and substance. Thirty years to wait for an justice is an incredibly long time and this is perhaps this may be the lesson we all need to carry forward.

(In)Human Rights in the “Compliant Environment”

In the aftermath of the Windrush generation debacle being brought into the light, Amber Rudd resigned, and a new Home Secretary was appointed. This was hailed by the government as a turning point, an opportunity to draw a line in the sand. Certainly, within hours of his appointment, Sajid Javid announced that he ‘would do right by the Windrush generation’. Furthermore, he insisted that he did not ‘like the phrase hostile’, adding that ‘the terminology is incorrect’ and that the term itself, was ‘unhelpful’. In its place, Javid offered a new term, that of; ‘a compliant environment’. At first glance, the language appears neutral and far less threatening, however, you do not need to dig too deep to read the threat contained within.

According to the Oxford Dictionary (2018) the definition of compliant indicates a disposition ‘to agree with others or obey rules, especially to an excessive degree; acquiescent’. Compliance implies obeying orders, keeping your mouth shut and tolerating whatever follows. It offers, no space for discussion, debate or dissent and is far more reflective of the military environment, than civilian life. Furthermore, how does a narrative of compliance fit in with a twenty-first century (supposedly) democratic society?

The Windrush shambles demonstrates quite clearly a blatant disregard for British citizens and implicit, if not, downright aggression. Government ministers, civil servants, immigration officers, NHS workers, as well as those in education and other organisations/industries, all complying with rules and regulations, together with pressures to exceed targets, meant that any semblance of humanity is left behind. The strategy of creating a hostile environment could only ever result in misery for those subjected to the State’s machinations. Whilst, there may be concerns around people living in the country without the official right to stay, these people are fully aware of their uncertain status and are thus unlikely to be highly visible. As we’ve seen many times within the CJS, where there are targets that “must” be met, individuals and agencies will tend to go for the low-hanging fruit. In the case of immigration, this made the Windrush generation incredibly vulnerable; whether they wanted to travel to their country of origin to visit ill or dying relatives, change employment or if they needed to call on the services of the NHS. Although attention has now been drawn to the plight of many of the Windrush generation facing varying levels of discrimination, we can never really know for sure how many individuals and families have been impacted. The only narratives we will hear are those who are able to make their voices heard either independently or through the support of MPs (such as David Lammy) and the media. Hopefully, these voices will continue to be raised and new ones added, in order that all may receive justice; rather than an off-the-cuff apology.

However, what of Javid’s new ‘compliant environment’? I would argue that even in this new, supposedly less aggressive environment, individuals such as Sonia Williams, Glenda Caesar and Michael Braithwaite would still be faced with the same impossible situation. By speaking out, these British women and man, as well as countless others, demonstrate anything but compliance and that can only be a positive for a humane and empathetic society.

Is Easter a criminological issue?

Spring is the time that many Christians relate with the celebration of Easter. For many the sacrament of Easter seals their faith; as in the end of torment and suffering, there is the resurrection of the head of the faith. All these are issues to consider in a religious studies blog and perhaps consider the existential implications in a philosophical discourse. How about criminology?

In criminology it provides great penological and criminological lessons. The nature of Jesus’s apprehension, by what is described as a mob, relates to ideas of vigilantism and the old non-professional watchmen who existed in many different countries around the world. The torture, suffered is not too dissimilar from the investigative interrogation unfortunately practiced even today around the world (overtly or covertly). His move from court to court, relates to the way we apply for judicial jurisdiction depending on the severity of the case and the nature of the crime. The subsequent trial; short and very purposefully focused to find Jesus guilty, is so reminiscent of what we now call a “kangaroo court” with a dose of penal appeasement and penal populism for good measure. The final part of this judicial drama, is played with the execution. The man on the cross. Thousands of men (it is not clear how many) were executed in this method.

For a historian the exploration of past is key, for a legal professional the study of black letter law principles and for a criminal justice practitioner the way methods of criminal processes altered in time. What about a reader in criminology? For a criminologist there are wider meanings to ascertain and to relate them to our fundamental understanding of justice in the depth of time. The events which unfolded two millennia back, relate to very current issues we read in the news and study in our curriculum. Consider arrest procedures including the very contested stop and search practice. The racial inequalities in court and the ongoing debates on jury nullification as a strategy to combat them. Our constant opposition as a discipline to the use of torture at any point of the justice system including the use of death penalty. In criminology we do not simply study criminal justice, but equally important, that of social justice. In a recent talk in response to a student’s question I said that that at heart of each criminologist is an abolitionist. So, despite our relationship and work with the prison service, we remain hopeful for a world where the prison does not become an inevitable sentence but an ultimate one, and one that we shall rarely use. Perhaps if we were to focus more on social justice and the inequalities we may have far less need for criminal justice

Evidently Easter has plenty to offer for a criminologist. As a social discipline, it allows us to take stock and notice the world around us, break down relationships and even evaluate complex relationships defying world belief systems. Apparently after the crucifixion there was also a resurrection; for more information about that, search a theological blog. Interestingly in his Urbi et Orbi this year the Pope spoke for the need for world leaders to focus on social justice.

A Failing Cultural or Criminal Justice System?

Sallek is a graduate from the MSc Criminology. He is currently undertaking doctoral studies at Stellenbosch University, South Africa.

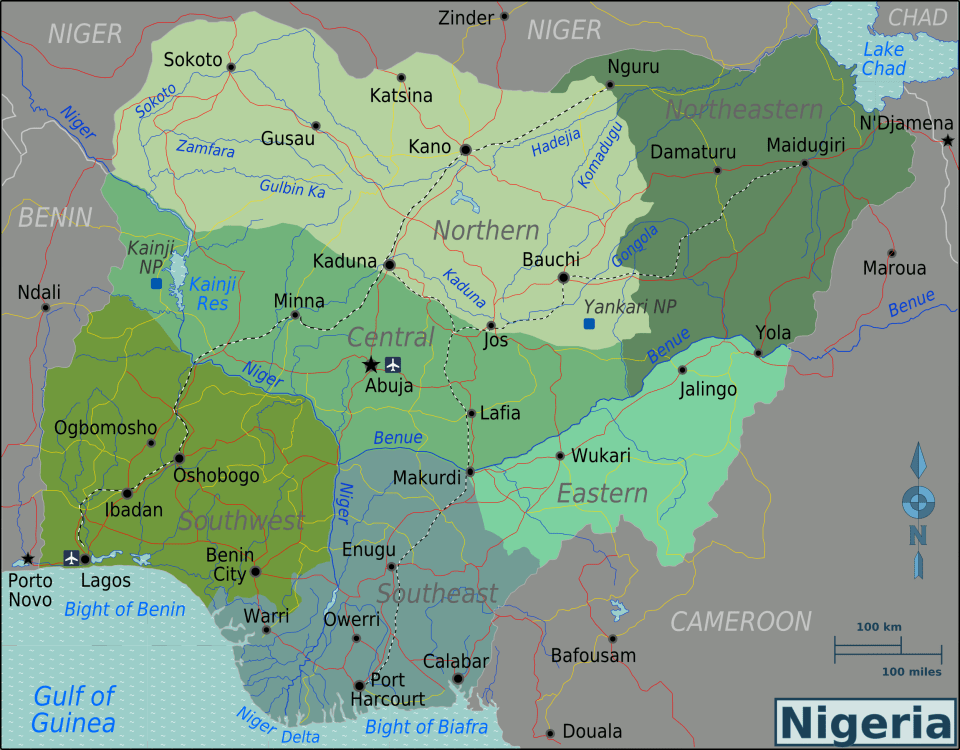

In this piece, I reflect on the criminal justice system in Nigeria showing how a cultural practice evoked a social problematique, one that has exposed the state of the criminal justice system of the country. While I dissociate myself from the sect, I assume the place of the first person in contextualizing this discourse.

In line with the norm, our mothers were married to them. Having paid the bride wealth, even though they have no means, no investment and had little for their upkeep, they married as many as they could satisfy. In our number, they birth as many as their strength could allow, but, little did we know the intention is to give us out to tutelage from religious teachers once we could speak. So, we grew with little or no parental care, had little or no contact, and the street was to become our home where we learnt to be tough and strong. There we learnt we are the Almajiri (homeless children), learning and following the way and teaching of a teacher while we survived on alms and the goodwill of the rich and the sympathetic public.

As we grew older, some learnt trades, others grew stronger in the streets that became our home, a place which toughened and strengthened us into becoming readily available handymen, although our speciality was undefined. We became a political tool servicing the needs of desperate politicians, but, when our greed and their greed became insatiable, they lost their grip on us. We became swayed by extremist teachings, the ideologies were appealing and to us, a worthy course, so, we joined the sect and began a movement that would later become globally infamous. We grew in strength and might, then they coerced us into violence when in cold blood, their police murdered our leader with impunity. No one was held responsible; the court did nothing, and no form of judicial remedy was provided. So, we promised full scale war and to achieve this, we withdrew, strategized, and trained to be surgical and deadly.

The havoc we created was unimaginable, so they labelled us terrorists and we lived the name, overwhelmed their police, seized control of their territories, and continued to execute full war of terror. We caused a great humanitarian crisis, displaced many, and forced a refugee crisis, but, their predicament is better than our childhood experience. So, when they sheltered these displaced people in camps promising them protection, we defiled this fortress and have continued to kill many before their eyes. The war they waged on us using their potent monster, the military continuous to be futile. They lied to their populace that they have overpowered us, but, not only did we dare them, we also gave the military a great blow that no one could have imagined we could. The politicians promised change, but we proved that it was a mere propaganda when they had to negotiate the release of their daughters for a ransom which included releasing our friends in their custody. After this, we abducted even more girls at Dapchi. Now I wonder, these monsters we have become, is it our making, the fault of our parents, a failure of the criminal justice system, or a product of society?