Home » Incarceration (Page 3)

Category Archives: Incarceration

Halloween Prison Tourism

Haley Read is an Associate Lecturer teaching modules in the first and third years.

Yes, that spooky time of the year is upon us! Excited at the prospect of being free to do something at Halloween but deterred by the considerable amount of effort required to create an average-looking carved pumpkin face, I Google, ‘Things to do for Halloween in the Midlands’.

I find that ‘prison (and cell) ghost tours’ are being advertised for tourists who can spend the night where (in)famous offenders once resided and the ‘condemned souls’ of unusual and dangerous inmates still ‘haunt’ the prison walls today. I do a bit more searching and find that more reputable prison museums are also advertising similar events, which promise a ‘fun’ and ‘action packed’ family days out where gift shops and restaurants are available for all to enjoy.

Of course, the lives of inmates who suffered from harsh and brutal prison regimes are commodified in all prison museums, and not just at Halloween related events. What appears concerning is that these commercial and profit-based events seem to attract visitors through promotional techniques which promise to entertain, reinforce common sensical, and at times fabricated (see Barton and Brown, 2015 for examples) understandings of history, crime and punishment. These also present sensationalistic a-political accounts of the past in order to appeal to popular fascinations with prison-related gore and horror; all of which aim to attract customers.

The fascination with attending places of punishment is nothing new. Barton and Brown (2015) illustrates this with historical accounts of visitors engaging in the theatrics of public executions and of others who would visit punishment-based institutions out of curiosity or to amuse themselves. And I suppose modern commercial prison tourism could be viewed as an updated way to satisfy morbid curiosities surrounding punishment and the prison.

The reason that this concerns me is that despite having the potential to educate others and challenge prison stereotypes that are reinforced through the media and True Crime books, commercialised prison events aim to entertain as well as inform. This then has the danger of cementing popular and at times fictional views on the prison that could be seen as being historically inaccurate. Barton and Brown (2015) exemplify this idea by noting that prison museums present inmates as being unusual, harsh historical punishments as being necessary and the contemporary prison system as being progressive and less punitive. However, opposing views suggest that offenders are more ordinary than unusual, that historical punishments are brutal rather than necessary and that many contemporary prisons are viewed as being newer versions of punitive discipline rather than progressive.

Perhaps it could be that presenting a simplified, uncritical and stereotyped version of the past as entertainment prevents prison tourists from understanding the true pains experienced by those who have been incarcerated within the prison (see Barton and Brown, 2015, Sim, 2009). Truer prison museum promotions could inform visitors of staff corruption, the detrimental social and psychological effects of the prison, and that inmates (throughout history) are more likely to be those who are poor, disempowered, previously victimised and at risk of violence and self-harm upon entering prison. But perhaps this would attract less visitors/profit…And so for another year I will stick to carving pumpkins.

Photo by Markus Spiske temporausch.com on Pexels.com

Barton, A and Brown, A. (2015) Show me the Prison! The Development of Prison Tourism in the UK. Crime Media and Culture. 11(3), pp.237-258. Doi: 10.1177/1741659015592455.

Sim, J. (2009) Punishment and Prisons: Power and the Carceral State. London: Sage.

‘I read the news today, oh boy’

The English army had just won the war

The English army had just won the war

A crowd of people turned away

But I just had to look

Having read the book

(Lennon and McCartney, 1967),

The news these days, without fail, is terrible. Wherever you look you are confronted by misery, death, destruction and terror. Regular news channels and social media bombard us with increasingly horrific tales of people living and dying under tremendous pressure, both here in the UK and elsewhere in the world. Below are just a couple of examples drawn from the mainstream media over the space of a few days, each one an example of individual or collective misery. None of them are unique and they all made the headlines in the UK.

‘Deaths of UK homeless people more than double in five years’

‘Syria: 500 Douma patients had chemical attack symptoms, reports say’

‘London 2018 BLOODBATH: Capital on a knife edge as killings SOAR to 56 in three months’

So how do we make sense of these tumultuous times? Do we turn our backs and pretend it has nothing to do with us? Can we, as Criminologists, ignore such events and say they are for other people to think about, discuss and resolve?

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, Stanley Cohen, posed a similar question; ‘How will we react to the atrocities and suffering that lie ahead?’ (2001: 287). Certainly his text States Of Denial: Knowing about Atrocities and Suffering makes clear that each of us has a part to play, firstly by ‘knowing’ that these things happen; in essence, bearing witness and acknowledging the harm inherent in such atrocities. But is this enough?

Cohen, persuasively argues, that our understanding has fundamentally changed:

The political changes of the last decade have radically altered how these issues are framed. The cold-war is over, ordinary “war” does not mean what it used to mean, nor do the terms “nationalism”, “socialism”, “welfare state”, “public order”, “security”, “victim”, “peace-keeping” and “intervention” (2001: 287).

With this in mind, shouldn’t our responses as a society, also have changed, adapted to these new discourses? I would argue, that there is very little evidence to show that this has happened; whilst problems are seemingly framed in different ways, society’s response continues to be overtly punitive. Certainly, the following responses are well rehearsed;

- “move the homeless on”

- “bomb Syria into submission”

- “increase stop and search”

- “longer/harsher prison sentences”

- “it’s your own fault for not having the correct papers?”

Of course, none of the above are new “solutions”. It is well documented throughout much of history, that moving social problems (or as we should acknowledge, people) along, just ensures that the situation continues, after all everyone needs somewhere just to be. Likewise, we have the recent experiences of invading Iraq and Afghanistan to show us (if we didn’t already know from Britain’s experiences during WWII) that you cannot bomb either people or states into submission. As criminologists, we know, only too well, the horrific impact of stop and search, incarceration and banishment and exile, on individuals, families and communities, but it seems, as a society, we do not learn from these experiences.

Yet if we were to imagine, those particular social problems in our own relationships, friendship groups, neighbourhoods and communities, would our responses be the same? Wouldn’t responses be more conciliatory, more empathetic, more helpful, more hopeful and more focused on solving problems, rather than exacerbating the situation?

Next time you read one of these news stories, ask yourself, if it was me or someone important to me that this was happening to, what would I do, how would I resolve the situation, would I be quite so punitive? Until then….

Whoever fights monsters should see to it that in the process he does not become a monster. And when you look long into an abyss, the abyss also looks into you (Nietzsche, 1886/2003: 146)

References:

Cohen, Stanley, (2001), States Of Denial: Knowing about Atrocities and Suffering, (Cambridge: Polity Press)

Lennon, John and McCartney, Paul, (1967), A Day in the Life, [LP]. Recorded by The Beatles in Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, EMI Studios: Parlaphone

Nietzsche, Friedrich, (1886/2003), Beyond Good and Evil: Prelude to a Philosophy of the Future, tr. from the German by R. J. Hollingdale, (London: Penguin Books)

Out early on good behaviour

Dr Stephen O’Brien is the Dean for the Faculty of Health and Society at the University of Northampton

The other week I had the opportunity to visit one of our local prisons with academic colleagues from our Criminology team within the Faculty of Health and Society at the University of Northampton. The prison in question is a category C closed facility and it was my very first visit to such an institution. The context for my visit was to follow up and review the work completed by students, prisoners and staff in the joint delivery of an academic module which forms part of our undergraduate Criminology course. The module entitled “Beyond Justice” explores key philosophical, social and political issues associated with the concept of justice and the journeys that individuals travel within the criminal justice system in the UK. This innovative approach to collaborative education involving the delivery of the module to students of the university and prisoners was long in its gestation. The module itself had been delivered over several weeks in the Autumn term of 2017. What was very apparent from the start of this planned visit was how successful the venture had been; ground-breaking in many respects with clear impact for all involved. Indeed, it has been way more successful than anyone could have imagined when the staff embarked on the planning process. The project is an excellent example of the University’s Changemaker agenda with its emphasis upon mobilising University assets to address real life social challenges.

My particular visit was more than a simple review and celebration of good Changemaker work well done. It was to advance the working relationship with the Prison in the signing of a memorandum of understanding which outlined further work that would be developed on the back of this successful project. This will include; future classes for university/prison students, academic advancement of prison staff, the use of prison staff expertise in the university, research and consultancy. My visit was therefore a fruitful one. In the run up to the visit I had to endure all the usual jokes one would expect. Would they let me in? More importantly would they let me out? Clearly there was an absolute need to be on my best behaviour, keep my nose clean and certainly mind my Ps and Qs especially if I was to be “released”. Despite this ribbing I approached the visit with anticipation and an open mind. To be honest I was unsure what to expect. My only previous conceptual experience of this aspect of the criminal justice system was many years ago when I was working as a mental health nurse in a traditional NHS psychiatric hospital. This was in the early 1980s with its throwback to a period of mental health care based on primarily protecting the public from the mad in society. Whilst there had been some shifts in thinking there was still a strong element of the “custodial” in the treatment and care regimen adopted. Public safety was paramount and many patients had been in the hospital for tens of years with an ensuing sense of incarceration and institutionalisation. These concepts are well described in the seminal work of Barton (1976) who described the consequences of long term incarceration as a form of neurosis; a psychiatric disorder in which a person confined for a long period in a hospital, mental hospital, or prison assumes a dependent role, passively accepts the paternalist approach of those in charge, and develops symptoms and signs associated with restricted horizons, such as increasing passivity and lack of motivation. To be fair mental health services had been transitioning slowly since the 1960s with a move from the custodial to the therapeutic. The associated strategy of rehabilitation and the decant of patients from what was an old asylum to a more community based services were well underway. In many respects the speed of this change was proving problematic with community support struggling to catch up and cope with the numbers moving out of the institutions.

My only other personal experience was when I spent a night in the cells of my local police station following an “incident” in the town centre. This was a case of being in the wrong place at the wrong time. (I know everyone says that, but in this case it is a genuine explanation). However, this did give me a sense of what being locked up felt like albeit for a few hours one night. When being shown one of the single occupancy cells at the prison those feelings came flooding back. However, the thought of being there for several months or years would have considerably more impact. The accommodation was in fact worse than I had imagined. I reflected on this afterwards in light of what can sometimes be the prevailing narrative that prison is in some way a cushy number. The roof over your head, access to a TV and a warm bed along with three square meals a day is often dressed up as a comfortable daily life. The reality of incarceration is far from this view. A few days later I watched Trevor MacDonald report from Indiana State Prison in the USA as part of ITV’s crime and punishment season. In comparison to that you could argue the UK version is comfortable but I have no doubt either experience would be, for me, an extreme challenge.

There were further echoes of my mental health experiences as I was shown the rehabilitation facilities with opportunities for prisoners to experience real world work as part of their transition back into society. I was impressed with the community engagement and the foresight of some big high street companies to get involved in retraining and education. This aspect of the visit was much better than I imagined and there is evidence that this is working. It is a strict rehabilitation regime where any poor behaviour or departure from the planned activity results in failure and loss of the opportunity. This did make me reflect on our own project and its contribution to prisoner rehabilitation. In education, success and failure are norms and the process engenders much more tolerance of what we see as mistakes along the way. The great thing about this project is the achievement of all in terms of both the learning process and outcome. Those outcomes will be celebrated later this month when we return to the prison for a special celebration event. That will be the moment not only to celebrate success but to look to the future and the further work the University and the Prison can do together. On that occasion as on this I do expect to be released early for good behaviour.

Reference

Barton, R., (1976) Institutional Neurosis: 3rd edition, Butterworth-Heinemann, London.

Modern University or New University?

As I am outside the prison walls on another visit I look at the high walls that keep people inside incarcerated. This is an institution designed to keep people in and it is obvious from the outside. This made me wonder what is a University designed for? Are we equally obvious to the communities in which we live as to what we are there for? These questions have been posed before but as we embark in a new educational environment I begin to wonder.

There are city universities, campuses in towns and the countryside, new universities and of course old, even, medieval universities. All these institutions have an educational purpose in common at a high level but that is more or less it. Traditionally, academia had a specific mandate of what they were meant to be doing but this original focus was coming from a era when computers, the electronic revolution and the knowledge explosion were unheard of. I still amuse my students by my recollections of going through an old library, looking at their card catalogue in order to find the books I wanted for my essay.

Since then, email has become the main tool for communication and blackboard or other virtual learning environments are growing into becoming an alternative learning tool in the arsenal of each academic. In this technologically advanced, modern world it is pertinent to ask if the University is the environment that it once was. The introduction of fees, and the subsequent political debates on whether to raise the fees or get rid of them altogether. This debate has also introduced an consumerist dimension to higher education that previous learners did not encounter. For some colleagues this was a watershed moment in the mandate of higher education and the relationship between tutor and tutee. Recently, a well respected colleague told me how inspired she was to pursue a career in academia when she watched Willy Russell’s theatrical masterpiece Educating Rita. It seems likely that this cultural reference will be lost to current students and academics. A clear sign of things moving on.

So what is a University for in the 21st century? In my mind, the university is an institution of education that is open to its community and accessible to all people, even those who never thought that Higher Education is for them. Physically, there may not be walls around but for many people who never had the opportunity to enjoy a higher education, there may be barriers. It is perhaps the purpose of the new university to engage with the community and invite the people to embrace it as their community space. Our University’s relocation to the heart of the town will make our presence more visible in town and it is a great opportunity for the University to be reintroduced to the local community. As one of the few Changemaker universities in the country, a title that focuses on social change and entrepreneurship, connecting with the community is definitely a fundamental objective. In this way it will offer its space up for meaningful discussions on a variety of issues, academic or not, to the community saying we are a public institution for all. After all, this is part of how we understand criminology’s role. In a recent discussion we have been talking about criminology in the community; a public criminology. One of the many reasons why we work so hard to teach criminology in prisons.

“Letters from America”: III

For those of you who follow The Criminology Team on Facebook you might have caught @manosdaskalou and I live from Eastern State Penitentiary [ESP]. In this entry, I plan to reflect on that visit in a little more depth.

For those of you who follow The Criminology Team on Facebook you might have caught @manosdaskalou and I live from Eastern State Penitentiary [ESP]. In this entry, I plan to reflect on that visit in a little more depth.

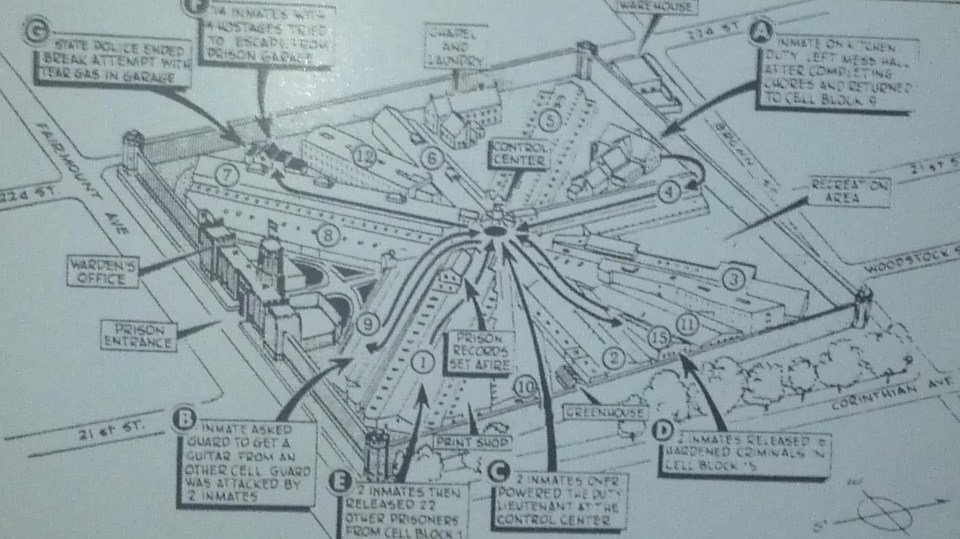

We first visited ESP in 2011 when the ASC conference was held in Washington, DC. That visit has never left me for a number of reasons, not least the lengths societies are prepared to go in order to tackle crime. ESP is very much a product of its time and demonstrates extraordinarily radical thinking about crime and punishment. For those who have studied the plans for Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon there is much which is familiar, not least the radial design (see illustration below).

This is an institution designed to resolve a particular social problem; crime and indeed deter others from engaging in similar behaviour through humane and philosophically driven measures. The Philadelphia Society for Alleviating the Miseries of Public Prisons* was philanthropic and guided by religious principles. This is reflected in the term penitentiary; a place for sinners to repent and In turn become truly penitent.

This philosophy was distinct and radical with a focus on reformation of character rather than brutal physical punishment. Of course, scholars such as Ignatieff and Foucault have drawn attention to the inhumanity of such a regime, whether deliberate or unintentional, but that should not detract from its groundbreaking history. What is important, as criminologists, is to recognise ESP’s place in the history of penology. That history is one of coercion, pleading, physical and mental brutality and still permeates all aspects of incarceration in the twenty-first century. ESP have tried extremely hard to demonstrate this continuum of punishment, acknowledging its place among many other institutions both home and abroad.

For me the question remains; can we make an individual change their behaviour through the pains of incarceration? I have argued previously in this blog in relation to Conscientious Objectors, that all the evidence suggests we cannot. ESP, as daunting as it may have been in its heyday, would also seem to offer the same answer. Until society recognises the harm and futility of incarceration it is unlikely that penal reform, let alone abolition, will gain traction.

*For those studying CRI1007 it is worth noting the role of Benjamin Rush in this organisation.

About a year ago, as a team we started this blog in order to relate criminological ideas into everyday life. News, events and markers on our social calendar became sources of inspiration and inquiry. Within a year, we have managed somehow to reflect on the academic cycle, some pretty heavy social issues that evoked our passions and interests. Those of you who read our entries, thank you for taking the time, especially those who left comments with your own experiences and ideas.

About a year ago, as a team we started this blog in order to relate criminological ideas into everyday life. News, events and markers on our social calendar became sources of inspiration and inquiry. Within a year, we have managed somehow to reflect on the academic cycle, some pretty heavy social issues that evoked our passions and interests. Those of you who read our entries, thank you for taking the time, especially those who left comments with your own experiences and ideas.