Home » George Orwell

Category Archives: George Orwell

LET THEM EAT SOUP

Introduction

What is a can of soup? If you ask a market expert, it is a high-profit item currently pushing £2.30 (branded) in some UK shops[i]. If you ask a historian[ii], it is the very bedrock of organised charity-the cheapest, easiest way to feed a penniless and hungry crowd.

The high price of something so basic, like a £2.30 can of soup, is a massive conundrum when you remember that soup’s main historical job was feeding poor people for almost nothing. Soup, whose name comes from the old word Suppa[iii](meaning broth poured over bread), was chosen by charities because it was cheap, could be made in huge pots, and best of all could be ‘stretched’ with water to feed even more people on a budget[iv].

In 2025, the whole situation is upside down. The price of this simple food has jumped because of “massive economic problems and big company greed[v]. At the same time, the need for charity has exploded with food bank use soaring by an unbelievable 51% compared to 2019[vi]. When basic food is expensive and charity is overwhelmed, it means our country’s safety net is broken.

For those of us who grew up in the chilly North, soup is more than a commodity: it is a core memory. I recall winter afternoons in Yorkshire, scraping frost off the window, knowing a massive pot of soup was bubbling away. Thick, hot and utterly cheap. Our famous carrot and swede soup cost pennies to make, tasted like salvation and could genuinely “fix you.” The modern £2.30 price tag on a can feels like a joke played on that memory, a reminder that the simplest warmth is now reserved for those who can afford the premium.

This piece breaks down some of the reasons why a can of soup costs so much, explores the 250-year-old long, often embarrassing history of soup charity in Britain and shows how the two things-high prices and huge charity demand-feed into a frustrating cycle of managed hunger.

Why Soup Costs £2.30

The UK loves its canned soup: it is a huge business worth hundreds of millions of pounds every year[vii], but despite being a stable market, prices have been battered by outside events.

Remember that huge cost of living squeeze? Food inflation prices peaked at 19.1% in 2023, the biggest rise in 40 years[viii]. Even though things have calmed down slightly, food prices jumped again to 5.1% in August 2025, remaining substantially elevated compared to the overall inflation rate of 3.8% in the same month[ix]. This huge price jump hits basic stuff the hardest, which means that poor people get hurt the most.

Why the drama? A mix of global chaos (like the Ukraine conflict messing up vegetable oil and fertiliser supplies) and local headaches (like the extra costs from Brexit) have made everything more expensive to produce[x].

Here’s the Kicker: Soup ingredients themselves are super cheap. You can make a big pot of vegetable soup at home for about 66p a serving, but a can of the same stuff? £2.30. Even professional caterers can buy bulk powdered soup mix for just 39p per portion[xi].

The biggest chunk of that price has nothing to do with the actual carrots and stock. It’s all the “extras”. You must pay for- the metal can, the flashy label and the marketing team that tries to convince you this soup is a “cosy hug”, and, most importantly everyone’s cut along the way.

Big supermarkets and shops are the main culprits. They need a massive 30-50% profit margin on that can for just putting it on the shelf[xii]. Because people have to buy food to live (you can’t just skip dinner) big companies can grab massive profits, turning something that you desperately need into something that just makes them rich.

This creates the ultimate cruel irony. Historically, soup was accessible because it was simple and cheap. Now, the people who are too busy, too tired or too broke to cook from scratch-the working poor are forced to buy the ready-made cans[xiii]. They end up paying the maximum premium for the convenience they need most, simply because they don’t have the time or space to do it the cheaper way.

How Charity Got Organised

The idea of soup as charity is ancient, but the dedicated “soup kitchen” really took off in late 18th century Britain[xiv].

The biggest reasons were the chaos after the Napoleonic wars and the rise of crowded industrial towns, which meant that lots of people had no money if their work dried up. By 1900 England had gone from a handful of soup kitchens to thousands of them[xv].

The first true soup charity in England was likely La Soupe, started by Huguenot refugees in London in the late 17th Century[xvi]. They served beef soup daily-a real community effort before the phrase “soup kitchen” was even popular.

Soup was chosen as the main charitable weapon because it was incredibly practical. It was cheap, healthy and could be made in enormous quantities. Its real superpower was that it could be “stretched” by adding more water allowing charities to serve huge numbers of people for minimum cost[xvii].

These kitchens were not just about food; they were tools for managing poor people. During the “long nineteenth century” they often fed up to 30% of a local town’s population in winter[xviii]. This aid ran alongside the stern rules of the Old Poor Laws which sorted people into “deserving” (the sick or old) and the ‘undeserving’ (those considered lazy).

The queues, the rules, and the interviews at soup kitchens were a kind of “charity performance” a public way of showing who was giving and who was receiving, all designed to reinforce class differences and tell people how to behave.

The Stigma and Shame of Taking The Soup

Getting a free bowl of soup has always come with a huge dose of shame. It’s basically a public way of telling you “We are the helpful rich people and you are the unfortunate hungry one” Even pictures in old newspapers were designed to make the donors look amazing whilst poor recipients were closely watched[xix].

Early British journalists like Bart Kennedy used to moan about the long, cold queues and how staff would ask “degrading questions” just before you got your soup[xx]. Basically, you had to pass a misery test to get a bowl of watery vegetables, As one 19th Century writer noted, the typical soup house was rarely cleaned, meaning the “aroma of old meals lingers in corners…when the steam from the freshly cooked vegetables brings them back to life”[xxi].

For the recipient, the act of accepting aid became a profound assault on their humanity. The writer George Orwell, captured this degradation starkly, suggesting that a man enduring prolonged hunger “is not a man any longer, only a belly with a few accessory organs”[xxii]. That is the tragic joke here, you are reduced to a stomach that must beg.

By the late 19th Century, people started criticising soup kitchens arguing that they “were blamed for creating the problem they sought to alleviate”[xxiii]. The core problem remains today: giving someone a temporary food handout is just a “band-aid” solution that treats the symptom but ignores the real disease i.e. not enough money to live on.

This critique was affirmed during the Great Depression in Britain, when mobile soup kitchens and dispersal centres became a feature of the British urban landscape[xxiv]. The historical lesson is clear: private charity simply cannot solve a national economic disaster.

The ultimate failure of the system as the historian A.J.P. Taylor pointed out is that the poor demanded dignity. “Soup kitchens were the prelude to revolution, The revolutionaries might talk about socialism, those who actually revolted wanted ‘the right to work’-more capitalism, not it’s abolition[xxv]” They wanted a stable job, not perpetual charity.

Expensive Soup Feeds The Food Bank

The UK poverty crisis means that 7.5 million people (11% of the population) were in homes that did not have enough food in 2023/24[xxvi]. The Trussell Trust alone gave out 2.9 million emergency food parcels in 2024/2025[xxvii]. Crucially, poverty has crept deeper into the workforce: research indicates that three in every ten people referred to in foodbanks in 2024 were from working households[xxviii]. They have jobs but still can’t afford the supermarket prices.

The charities themselves are struggling, hit by a “triple whammy” of rising running costs (energy, rent) and fewer donations[xxix]. This means that many charities have had to cut back, sometimes only giving out three days food instead of a week[xxx]. The safety net in other words is full of holes.

The necessity of navigating poverty systems just to buy food makes people feel trapped and hopeless which is a terrible way to run a country[xxxi].

Modern food banks are still stuck in the old ways of the ‘deserving poor.’ They usually make you get a formal referral—a special voucher—from a professional like a doctor, a Jobcentre person, or the Citizens Advice bureau[xxxii].It’s like getting permission from three different people to have a can of soup.

Charity leaders know this system is broken. The Chief Executive of the Trussell Trust has openly said that food banks are “not the answer” and are just a “fraying sticking plaster[xxxiii].” The system forces a perpetual debate between temporary relief and systemic reform[xxxiv]. The huge growth of private charity, critics argue, just gives the government an excuse to cut back on welfare, pretending that kind volunteers can fix the problem for them[xxxv].

The final, bitter joke links the expensive soup back to the charity meant to fix the cost. Big food companies use inflation to jack up prices and boost profits. Then, they look good by donating their excess stock—often the highly processed, high-profit stuff—to food banks.

This relationship is called the “hunger industrial complex”[xxxvi]. The high-margin, heavily processed canned soup—the quintessential symbol of modern pricing failure—often becomes a core component of the charitable food parcel. The high price charged for the commodity effectively pays for the charity that manages the damage the high price caused[xxxvii]. You could almost call it “Soup-er cyclical capitalism.”

Conclusion

The journey from the 18th-century charitable pot to the 21st-century £2.30 can of soup shows a deep failure in our society. Soup, the hero of cheap hunger relief, has become too pricey for the people who need it most. This cost is driven by profit, not ingredients.

This pricing failure traps poor people in expensive choices, forcing them toward overwhelmed charities. The modern food bank, like the old soup kitchen, acts as a temporary fix that excuses the government from fixing the root cause: low income. As social justice campaigner Bryan Stevenson suggests, “Poverty is the parent of revolution and crime”[xxxviii]. No amount of £2.30 soup can mask the fact that hunger is fundamentally an issue of “justice,” not merely “charity”.

Fixing this means shifting focus entirely. We must stop just managing hunger with charity[xxxix] and instead eliminate the need for charity by making sure everyone has enough money to live and buy their own food. This requires serious changes: regulating the greedy markups on basic food and building a robust state safety net that guarantees a decent income[xl]. The price of the £2.30 can is not just inflation: it’s a receipt for systemic unfairness.

[i]Various Contributors, ‘Reddit Discussion on High Soup Prices’ (Online Forum, 2023) https://www.reddit.com/r/CasualUK/comments/1eooo3o/why_has_soup_gotten_so_expensive

[ii] Philip J Carstairs, ‘A generous helping? The archaeology of Soup Kitchens and their role in post-medieval philanthropy 1790-1914 (PhD Thesis, University of Leicester 2022) https://figshare.le.ac.uk/articles/thesis/A_generous_helping_The_archaeology_of_soup_kitchens_and_their_role_in_post-medieval_philanthropy_1790-1914/21187117?file=37564186

[iii] Soup – etymology, origin & meaning[iii] https://www.etymonline.com/word/soup

[iv] Philip J Carstairs, ‘A generous helping? The archaeology of soup kitchens and their role in post-medieval philanthropy 1790–1914’ (Summary, University of Leicester 2022)(https://figshare.le.ac.uk/articles/thesis/A_generous_helping_The_archaeology_of_soup_kitchens_and_their_role_in_post-medieval_philanthropy_1790-1914/21187117)

[v] ONS, ‘Food Inflation Data, UK: August 2025’ (Trading Economics Data) https://tradingeconomics.com/united-kingdom/food-inflation

[vi] The Trussell Group-End Of Year Foodbank Stats

https://www.trussell.org.uk/news-and-research/latest-stats/end-of-year-stats

[vii] GlobalData, ‘Ambient Soup Market Size, Growth and Forecast Analytics, 2023-2028’ (Market Report, 2023) https://www.globaldata.com/store/report/uk-ambient-soup-market-analysis/

[viii] ONS, ‘Consumer Prices Index, UK: August 2025’ (Summary) https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/inflationandpriceindices

[ix] Food Standards Agency, ‘Food System Strategic Assessment’ (March 2023) https://www.food.gov.uk/research/food-system-strategic-assessment-trends-and-issues-impacted-by-uk-economic-condition

[x] Wholesale Soup Mixes (Brakes Foodservice) https://www.brake.co.uk/dry-store/soup/ambient-soup/bulk-soup-mixes

[xii] A Semuels, ‘Why Food Company Profits Make Groceries Expensive’ (Time Magazine, 2023) https://time.com/6269366/food-company-profits-make-groceries-expensive/

[xiii] Christopher B Barrett and others, ‘Poverty Traps’ (NBER Working Paper No. 13828, 2008) https://www.nber.org/system/files/chapters/c13828/c13828.pdf

[xiv] Philip J Carstairs, ‘A generous helping? The archaeology of soup kitchens and their role in post-medieval philanthropy 1790–1914’ (Summary, University of Leicester 2022)(https://figshare.le.ac.uk/articles/thesis/A_generous_helping_The_archaeology_of_soup_kitchens_and_their_role_in_post-medieval_philanthropy_1790-1914/21187117

[xv] Philip J Carstairs, ‘A generous helping? The archaeology of soup kitchens and their role in post-medieval philanthropy 1790–1914’ (Summary, University of Leicester 2022)(https://figshare.le.ac.uk/articles/thesis/A_generous_helping_The_archaeology_of_soup_kitchens_and_their_role_in_post-medieval_philanthropy_1790-1914/21187117

[xvi] The Soup Kitchens of Spitalfields (Blog, 2019) https://spitalfieldslife.com/2019/05/15/the-soup-kitchens-of-spitalfields/

[xvii] Birmingham History Blog, ‘Soup for the Poor’ (2016) https://birminghamhistoryblog.wordpress.com/2016/02/04/soup-for-the-poor/

[xviii] [xviii] Philip J Carstairs, ‘A generous helping? The archaeology of soup kitchens and their role in post-medieval philanthropy 1790–1914’ (Summary, University of Leicester 2022)(https://figshare.le.ac.uk/articles/thesis/A_generous_helping_The_archaeology_of_soup_kitchens_and_their_role_in_post-medieval_philanthropy_1790-1914/21187117

[xix] Journal Panorama, ‘Feeding the Conscience: Depicting Food Aid in the Popular Press’ (2019) https://journalpanorama.org/article/feeding-the-conscience/

[xx] Journal Panorama, ‘Feeding the Conscience: Depicting Food Aid in the Popular Press’ (2019) https://journalpanorama.org/article/feeding-the-conscience/

[xxi] Joseph Roth, Hotel Savoy (Quote on Soup Kitchens) https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/tag/soup-kitchens

[xxii] Convoy of Hope, (Quotes on Dignity and Poverty) https://convoyofhope.org/articles/poverty-quotes/

[xxiii] Philip J Carstairs, ‘A generous helping? The archaeology of soup kitchens and their role in post-medieval philanthropy 1790–1914’ (Summary, University of Leicester 2022)(https://figshare.le.ac.uk/articles/thesis/A_generous_helping_The_archaeology_of_soup_kitchens_and_their_role_in_post-medieval_philanthropy_1790-1914/21187117

[xxiv] Science Museum Group, ‘Photographs of Poverty and Welfare in 1930s Britain’ (Blog, 2017) https://blog.scienceandmediamuseum.org.uk/photographs-of-poverty-and-welfare-in-1930s-britain/

[xxv] AJ P Taylor, (Quote on Revolution) https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/tag/soup-kitchens

[xxvi] House of Commons Library, ‘Food poverty: Households, food banks and free school meals’ (CBP-9209, 2024) https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-9209/

[xxvii] Trussell Trust, ‘Factsheets and Data’ (2024/25) https://www.trussell.org.uk/news-and-research/latest-stats/end-of-year-stats

[xxviii] The Guardian, ‘Failure to tackle child poverty UK driving discontent’ (2025) https://www.theguardian.com/society/2025/sep/10/failure-tackle-child-poverty-uk-driving-discontent

[xxix] Charity Link, ‘The cost of living crisis and the impact on UK charities’ (Blog) https://www.charitylink.net/blog/cost-of-living-crisis-impact-uk-charities

[xxxi] The Soup Kitchen (Boynton Beach), ‘History’ https://thesoupkitchen.org/home/history/

[xxxii] Transforming Society, ‘4 uncomfortable realities of food charity’ (Blog, 2023) https://www.transformingsociety.co.uk/2023/12/01/4-uncomfortable-realities-of-food-charity-power-religion-race-and-cash

[xxxiii] The Trussell Group-End Of Year Foodbank Stats

https://www.trussell.org.uk/news-and-research/latest-stats/end-of-year-stats

[xxxiv] The Guardian, ‘Food banks are not the answer’ (2023) https://www.theguardian.com/society/2023/jun/29/food-banks-are-not-the-answer-charities-search-for-new-way-to-help-uk-families

[xxxv] The Guardian, ‘Britain’s hunger and malnutrition crisis demands structural solutions’ (2023) https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/commentisfree/2023/dec/27/britain-hunger-malnutrition->

[xxxvi] Jacques Diouf, (Quote on Hunger and Justice, 2007) https://www.hungerhike.org/quotes-about-hunger/

[xxxvii] Borgen Magazine, ‘Hunger Awareness Quotes’ (2024) https://www.borgenmagazine.com/hunger-awareness-quotes/

[xxxviii] he Guardian, ‘Failure to tackle child poverty UK driving discontent’ (2025) https://www.theguardian.com/society/2025/sep/10/failure-tackle-child-poverty-uk-driving-discontent

[xxxix] Charities Aid Foundation, ‘Cost of living: Charity donations can’t keep up with rising costs and demand’ (Press Release, 2023) https://www.cafonline.org/home/about-us/press-office/cost-of-living-charity-donations-can-t-keep-up-with-rising-costs-and-demand

[xl] The “Hunger Industrial Complex” and Public Health Policy (Journal Article, 2022) https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9437921/

What’s happened to the Pandora papers?

Sometime last week, I was amid a group of friends when the argument about the Pandora papers suddenly came up. In brief, the key questions raised were how come no one is talking about the Pandora papers again? What has happened to the investigations, and how come the story has now been relegated to the back seat within the media space? Although, we didn’t have enough time to debate the issues, I promised that I would be sharing my thoughts on this blog. So, I hope they are reading.

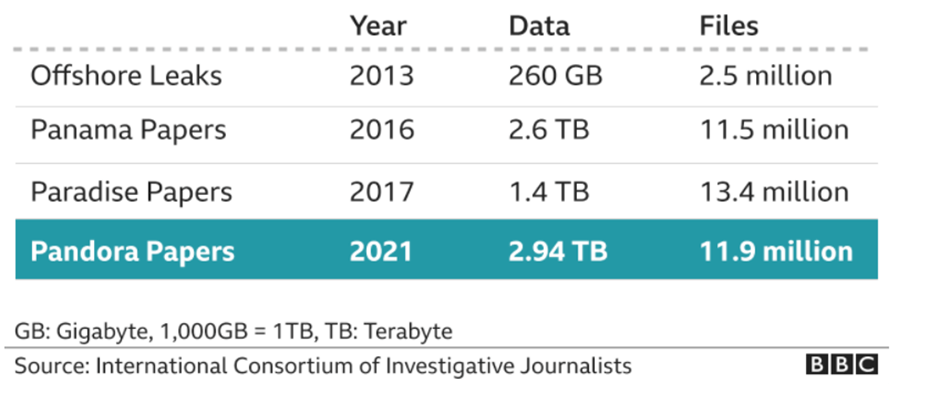

We can all agree that for many years, the issues of financial delinquencies and malfeasants have remained one of the major problems facing many societies. We have seen situations where Kleptocratic rulers and their associates loot and siphon state resources, and then stack them up in secret havens. Some of these Kleptocrats prefer to collect luxury Italian wines and French arts with their ill-gotten wealth, while others prefer to purchase luxury properties and 5-star apartments in Dubai, London and elsewhere. We find military generals participating in financial black operations, and we hear about law makers manipulating the gaps in the same laws they have created. In fact, in some spheres, we find ‘business tycoons’ exploiting violence-torn regions to smuggle gold, while in other spheres, some appointed public officers refuse to declare their assets because of fear of the future. Two years ago, we read about the two socialist presidents of the southern Spanish region and how they were found guilty of misuse of public funds. Totaling about €680m, you can imagine the good that could have been achieved in that region. We should also not forget the case of Ferdinand Marcos and his wife, both of whom (we are told) amassed over $10 billion during their reign in the Philippines. As we can see below that from the offshore leak of 2013 to the Panama papers of 2016 and then the 2017 Paradise papers, data leaks have continued to skyrocket. This simply demonstrates the level to which politicians and other official state representatives are taking to invest in this booming industry.

These stories are nothing new, we have always read about them – but then they fade away quicker than we expect. It is important to note that while some countries are swift in conducting investigation when issues like these arise, very little is known about others. So, in this blog, I will simply be highlighting some of the reasons why I think news relating to these issues have a short life span.

To start with, the system of financial corruption is often controlled and executed by those holding on to power very firmly. The firepower of their legal defence team is usually unmatchable, and the way they utilise their wealth and connections often make it incredibly difficult to tackle. For example, when leaks like these appear, some journalists are usually mindful of making certain remarks about the situation for the avoidance of being sued for libel and defamation of character. Secondly, financial crimes are always complex to investigate, and prosecution often takes forever. The problem of plurality in jurisdiction is also important in this analysis as it sometimes slows down the processes of investigation and prosecution. In some countries, there is something called ‘the immunity clause’, where certain state representatives are protected from being arraigned while in office. This issue has continued to raise concerns about the position of truth, power, and political will of governments to fight corruption. Another issue to consider is the issue of confidentiality clause, or what many call corporate secrecy in offshore firms. These policies make it very difficult to know who owns what or who is purchasing what. So, for as long as these clauses remain, news relating to these issues may continue to fade out faster than we imagine. Perhaps Young (2012) was right in her analysis of illicit practices in banking & other offshore financial centres when she insisted that ‘offshore financial centers such as the Cayman Islands, often labelled secrecy jurisdictions, frustrate attempts to recover criminal wealth because they provide strong confidentiality in international finance to legitimate clients as well as to the crooks and criminals who wish to hide information – thereby attracting a large and varied client base with their own and varied reasons for wanting an offshore account’, (Young 2012, 136). This idea has also been raised by our leader, Nikos Passas who believe that effective transparency is an essential component of unscrambling the illicit partnerships in these structures.

While all these dirty behaviours have continued to damage our social systems, they yet again remind us how the network of greed remains at the core centre of human injustice. I found the animalist commandant of the pigs in the novel Animal Farm, by George Orwell to be quite relevant in this circumstance. The decree spells: all animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others. This idea rightly describes the hypocrisy that we find in modern democracies; where citizens are made to believe that everyone is equal before the law but when in fact the law, (and in many instances more privileges) are often tilted in favour of the elites.

I agree with the prescription given by President Obama who once said that strengthening democracy entails building strong institutions over strong men. This is true because the absence of strong institutions will only continue to pave way for powerful groups to explore the limits of democracy. This also means that there must be strong political will to sanction these powerful groups engaging in this ‘thievocracy’. I know that political will is often used too loosely these days, but what I am inferring here is genuine determination to prosecute powerful criminals with transparency. This also suggests the need for better stability and stronger coordination of law across jurisdictions. Transparency should not only be limited to governments in societies, but also in those havens. It is also important to note that tackling financial crimes of the powerful should not be the duty of the state alone, but of all. Simply, it should be a collective effort of all, and it must require a joint action. By joint action I mean that civil societies and other private sectors must come together to advocate for stronger sanctions. We must seek collective participation in social movements because such actions can bring about social change – particularly when the democratic processes are proving unable to tackle such issues. Research institutes and academics must do their best by engaging in research to understand the depth of these problems as well as proffering possible solutions. Illicit financial delinquencies, we know, thrive when societies trivialize the extent and depth of its problem. Therefore, the media must continue to do their best in identifying these problems, just as we have consistently seen with the works of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and a few others. So, in a nutshell and to answer my friends, part of the reasons why issues like this often fade away quicker than expected has to do with some of the issues that I have pointed out. It is hoped however that those engaged in this incessant accretion of wealth will be confronted rather than conferred with national honors by their friends.

References

BBC (2021) Pandora Papers: A simple guide to the Pandora Papers leak. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-58780561 (Accessed: 26 May 2022)

Young, M.A., 2012. Banking secrecy and offshore financial centres: money laundering and offshore banking, Routledge