Home » Equity (Page 5)

Category Archives: Equity

Come Together

For much of the year, the campus is busy. Full of people, movement and voice. But now, it is quiet… the term is over, the marking almost complete and students and staff are taking much needed breaks. After next week’s graduations, it will be even quieter. For those still working and/or studying, the campus is a very different place.

This time of year is traditionally a time of reflection. Weighing up what went well, what could have gone better and what was a disaster. This year is no different, although the move to a new campus understandably features heavily. Some of the reflection is personal, some professional, some academic and in many ways, it is difficult to differentiate between the three. After all, each aspect is an intrinsic part of my identity.

Over the year I have met lots of new people, both inside and outside the university. I have spent many hours in classrooms discussing all sorts of different criminological ideas, social problems and potential solutions, trying always to keep an open mind, to encourage academic discourse and avoid closing down conversation. I have spent hour upon hour reading student submissions, thinking how best to write feedback in a way that makes sense to the reader, that is critical, constructive and encouraging, but couched in such a way that the recipient is not left crushed. I listened to individuals talking about their personal and academic worries, concerns and challenges. In addition, I have spent days dealing with suspected academic misconduct and disciplinary hearings.

In all of these different activities I constantly attempt to allow space for everyone’s view to be heard, always with a focus on the individual, their dignity, human rights and social justice. After more than a decade in academia (and even more decades on earth!) it is clear to me that as humans we don’t make life easy for ourselves or others. The intense individual and societal challenges many of us face on an ongoing basis are too often brushed aside as unimportant or irrelevant. In this way, profound issues such as mental and/or physical ill health, social deprivation, racism, misogyny, disablism, homophobia, ageism and many others, are simply swept aside, as inconsequential, to the matters at hand.

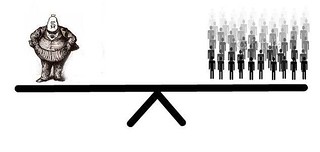

Despite long standing attempts by politicians, the media and other commentators to present these serious and damaging challenges as individual failings, it is evident that structural and institutional forces are at play. When social problems are continually presented as poor management and failure on the part of individuals, blame soon follows and people turn on each other. Here’s some examples:

Q. “You can’t get a job?”

A “You must be lazy?”

Q. “You’ve got a job but can’t afford to feed your family?

A. “You must be a poor parent who wastes money”

Q. “You’ve been excluded from school?”

A. “You need to learn how to behave?”

Q. “You can’t find a job or housing since you came out of prison?”

A. “You should have thought of that before you did the crime”

Each of these questions and answers sees individuals as the problem. There is no acknowledgement that in twenty-first century Britain, there is clear evidence that even those with jobs may struggle to pay their rent and feed their families. That those who are looking for work may struggle with the forces of racism, sexism, disablism and so on. That the reasons for criminality are complex and multi-faceted, but it is much easier to parrot the line “you’ve done the crime, now do the time” than try and resolve them.

This entry has been rather rambling, but my concluding thought is, if we want to make better society for all, then we have to work together on these immense social problems. Rather than focus on blame, time to focus on collective solutions.

Documenting inequality: how much evidence is needed to change things?

In our society, there is a focus on documenting inequality and injustice. In the discipline of criminology (as with other social sciences) we question and read and take notes and count and read and take more notes. We then come to an evidence based conclusion; yes, there is definite evidence of disproportionality and inequality within our society. Excellent, we have identified and quantified a social problem. We can talk and write, inside and outside of that social problem, exploring it from all possible angles. We can approach social problems from different viewpoints, different perspectives using a diverse range of theoretical standpoints and research methodologies. But what happens next? I would argue that in many cases, absolutely nothing! Or at least, nothing that changes these ingrained social problems and inequalities.

Even the most cursory examination reveals discrimination, inequality, injustice (often on the grounds of gender, race, disability, sexuality, belief, age, health…the list goes on), often articulated, the subject of heated debate and argument within all strata of society, but remaining resolutely insoluble. It is as if discrimination, inequality and injustice were part and parcel of living in the twenty-first century in a supposedly wealthy nation. If you don’t agree with my claims, look at some specific examples; poverty, gender inequality in the workplace, disproportionality in police stop and search and the rise of hate crime.

- Three years before the end of World War 2, Beveridge claimed that through a minor redistribution of wealth (through welfare schemes including child support) poverty ‘could have been abolished in Britain‘ prior to the war (Beveridge, 1942: 8, n. 14)

- Yet here we are in 2019 talking about children growing up in poverty with claims indicating ‘4.1 million children living in poverty in the UK’. In addition, 1.6 million parcels have been distributed by food banks to individuals and families facing hunger

- There is legal impetus for companies and organisations to publish data relating to their employees. From these reports, it appears that 8 out of 10 of these organisations pay women less than men. In addition, claims that 37% of female managers find their workplace to be sexist are noted

- Disproportionality in stop and search has long been identified and quantified, particularly in relation to young black males. As David Lammy’s (2017) Review made clear this is a problem that is not going away, instead there is plenty of evidence to indicate that this inequality is expanding rather than contracting

- Post-referendum, concerns were raised in many areas about an increase in hate crime. Most attention has focused on issues of race and religion but there are other targets of violence and intolerance

These are just some examples of inequality and injustice. Despite the ever-increasing data, where is the evidence to show that society is learning, is responding to these issues with more than just platitudes? Even when, as a society, we are faced with the horror of Grenfell Tower, exposing all manner of social inequalities and injustices no longer hidden but in plain sight, there is no meaningful response. Instead, there are arguments about who is to blame, who should pay, with the lives of those individuals and families (both living and dead) tossed around as if they were insignificant, in all of these discussions.

As the writer Pearl S. Buck made explicit

‘our society must make it right and possible for old people not to fear the young or be deserted by them, for the test of a civilization is in the way that it cares for its helpless members’ (1954: 337).

If society seriously wants to make a difference the evidence is all around us…stop counting and start doing. Start knocking down the barriers faced by so many and remove inequality and injustice from the world. Only then can we have a society which we all truly want to belong to.

Selected bibliography

Beveridge, William, (1942), Report of the Inter-Departmental Committee on Social Insurance and Allied Services, (HMSO: London)

Buck, Pearl S. (1954), My Several Worlds: A Personal Record, (London: Methuen)

Lammy, David, (2017), The Lammy Review: An Independent Review into the Treatment of, and Outcomes for, Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic Individuals in the Criminal Justice System, (London: Ministry of Justice)

The logic of racism

A few weeks ago, Danny Rose the Tottenham and England footballer was in the headlines for all the wrong reasons. He indicated he couldn’t wait to quit football because of racism in the game. He’s not the only black player that has spoken out, Raheem Stirling of Manchester City and England had previously raised the issue of racism and additionally pointed to the way the media portrayed black players.

I have no idea what its like to be subjected to racist abuse, how could I, I’m a white, middle class male? I have however, lived in and was for the best part of my life brought up in, a country dominated by racism. I lived in South Africa during the apartheid regime and to some extent I suppose I suffered some racism there, being English, a rooinek (redneck) but it was in the main limited to name calling from the other kids in school and after all, I was still white. There was some form of logic in apartheid; separate development was intended to maintain the dominance of the white population. Black people were viewed as inferior and a threat, kaffirs (non-believers) even though the majority were probably more devout than their white counterparts. I understand the logic of the discourse around ‘foreigners coming into this country and taking our jobs or abusing our services’, if you are told enough times by the media that this is the case then eventually you believe. I always say to colleagues they should read the Daily Mail newspaper and the like, to be informed about what news fables many of the population are fed.

I understand that logic even though I cannot ever condone it, but I just don’t get the logic around football and racism. Take the above two players, they are the epitome of what every footballing boy or girl would dream of. They are two of the best players in England, they have to be to survive in the English Premiership. In fact, the Premiership is one of the best football leagues in the world and has a significant proportion of black players in it, many from other parts of the world. It is what makes the league so good, it is what adds to the beautiful game.

So apart from being brilliant footballers, these two players are English, as English as I am, maybe more so if they spent all of their lives in this country and represent the country at the highest level. They don’t ‘sponge’ off the state, in fact through taxes they pay more than I and probably most of us will in my lifetime. They no doubt donate lots of money to and do work for charities, there aren’t many Premiership footballers that don’t. The only thing I can say to their detriment, being an avid Hammers fan, is that they play for the wrong teams in the Premiership. I’m not able to say much more about them because I do not know them. And therein lies my problem with the logic behind the racist abuse they and many other black players receive, where is that evidence to suggest that they are not entitled to support, praise and everything else that successful people should get. The only thing that sets them aside from their white fellow players is that they have black skins.

To make sense of this I have to conclude that the only logical answer behind the racism must be jealousy and fear. Jealousy regarding what they have and fear that somehow there success might be detrimental to the racists. They are better than the racists in so many ways, and the racists know this. Just as the white regime in South Africa felt threatened by the black population so too must the racists* in this country feel threatened by the success of these black players. Now admit that and I might be able to see the logic.

*I can’t call them football supporters because their behaviour is evidence that they are not.

Celebrations and Commemorations: What to remember and what to forget

Today is Good Friday (in the UK at least) a day full of meaning for those of the Christian faith. For others, more secularly minded, today is the beginning of a long weekend. For Blur (1994), these special days manifest in a brief escape from work:

Bank holiday comes six times a year

Days of enjoyment to which everyone cheers

Bank holiday comes with six-pack of beer

Then it’s back to work A-G-A-I-N

(James et al., 1994).

However, you choose to spend your long weekend (that is, if you are lucky enough to have one), Easter is a time to pause and mark the occasion (however, you might choose). This occasion appears annually on the UK calendar alongside a number other dates identified as special or meaningful; Bandi Chhorh Divas, Christmas, Diwali, Eid al-Adha, Father’s Day, Guys Fawkes’ Night, Hallowe’en, Hanukkah, Hogmanay, Holi, Mothering Sunday, Navaratri, Shrove Tuesday, Ramadan, Yule and so on. Alongside these are more personal occasions; birthdays, first days at school/college/university, work, graduations, marriages and bereavements. When marked, each of these days is surrounded by ritual, some more elaborate than others. Although many of these special days have a religious connection, it is not uncommon (in the UK at least) to mark them with non-religious ritual. For example; putting a decorated tree in your house, eating chocolate eggs or going trick or treating. Nevertheless, many of these special dates have been marked for centuries and whatever meanings you apply individually, there is an acknowledgement that each of these has a place in many people’s lives.

Alongside these permanent fixtures in the year, other commemorations occur, and it is here where I want to focus my attention. Who decides what will be commemorated and who decides how it will be commemorated? For example; Armistice Day which in 2018 marked 100 years since the end of World War I. This commemoration is modern, in comparison with the celebrations I discuss above, yet it has a set of rituals which are fiercely protected (Tweedy, 2015). Prior to 11.11.18 I raised the issue of the appropriateness of displaying RBL poppies on a multi-cultural campus in the twenty-first century, but to no avail. This commemoration is marked on behalf of individuals who are no longing living. More importantly, there is no living person alive who survived the carnage of WWI, to engage with the rituals. Whilst the sheer horror of WWI, not to mention WWII, which began a mere 21 years later, makes commemoration important to many, given the long-standing impact both had (and continue to have). Likewise, last year the centenary of (some) women and men gaining suffrage in the UK was deemed worthy of commemoration. This, as with WWI and WWII, was life-changing and had profound impact on society, yet is not an annual commemoration. Nevertheless, these commemoration offer the prospect of learning from history and making sure that as a society, we do much better.

Other examples less clear-cut include the sinking of RMS Titanic on 15 April 1912 (1,503 dead). An annual commemoration was held at Belfast’s City Hall and paying guests to the Titanic Museum could watch A Night to Remember. This year’s anniversary was further marked by the announcement that plans are afoot to exhume the dead, to try and identify the unknown victims. Far less interest is paid in her sister ship; RMS Lusitania (sank 1915, 1,198 dead). It is difficult to understand the hold this event (horrific as it was) still has and why attention is still raised on an annual basis. Of course, for the families affected by both disasters, commemoration may have meaning, but that does not explain why only one ship’s sinking is worthy of comment. Certainly it is unclear what lessons are to be learnt from this disaster.

Earlier this week, @anfieldbhoy discussed the importance of commemorating the 30th anniversary of the Hillsborough Disaster. This year also marks 30 years since the publication of MacPherson (1999) and Monday marks the 26th anniversary of Stephen Lawrence’s murder. In less than two months it will two years since the horror of Grenfell Tower. All of these events and many others (the murder of James Bulger, the shootings of Jean Charles de Menezes and Mark Duggan, the Dunblane and Hungerford massacres, to name but a few) are familiar and deemed important criminologically. But what sets these cases apart? What is it we want to remember? In the cases of Hillsborough, Lawrence and Grenfell, I would argue this is unfinished business and these horrible events remind us that, until there is justice, there can be no end.

However, what about Arthur Clatworthy? This is a name unknown to many and forgotten by most. Mr Clatworthy was a 20-year-old borstal boy, who died in Wormwood Scrubs in 1945. Prior to his death he had told his mother that he had been assaulted by prison officers. In the Houses of Parliament, the MP for Shoreditch, Mr Thurtle told a tale, familiar to twenty-first century criminologists, of institutional violence. If commemoration was about just learning from the past, we would all be familiar with the death of Mr Clatworthy. His case would be held up as a shining example of how we do things differently today, how such horrific events could never happen again. Unfortunately, that is not the case and Mr Clatworthy’s death remains unremarked and unremarkable. So again, I ask the question: who decides what it is worthy of commemoration?

Selected Bibliography:

James, Alexander, Rowntree, David, Albarn, Damon and Coxon, Graham, (1994), Bank Holiday, [CD], Recorded by Blur in Parklife, Food SBK, [RAK Studios]

Damned if you do, damned if you don’t: it’s a funny old world.

“Did you just look at me?” says Queen Anne to the footman and, as he shakes his head staring into oblivion clearly hoping this was not happening, she shouts “Look at me”. He reluctantly turns his head, looking at her in obvious discomfort when she screams “how dare you; close your eyes?” A short vignette from the television commercial advertising the award-winning film ‘The Favourite’ and very much a case of damned if you do and damned if you don’t for the poor hapless footman.

A few weeks ago, I accompanied my wife to a bear fair in London; she makes vintage bears as a hobby and occasionally takes to setting up a stall at some fair to sell them. As I sat behind the stall navel gazing and wandering what the football scores were, when I was going to get something to eat and when would be an appropriate time to go for a wander without giving off the vibe that enthusiasm was now waning, my wife said, ‘did you see that’? ‘What’ I asked peering over a number of furry Ursidae heads (I’m told they don’t bite)? ‘That woman in the orange top’ exclaimed my wife. Scouring the room for a woman that had been Tango’d, I listened to her explaining that a 30ish year old woman had just come out of the toilets wearing a bright orange top and emblazoned across her generous chest were the words ‘eye contact’. ‘I suppose it’s a good message’ said my wife as I settled back down to my navel gazing.

I thought about the incident, if you can call it that, on the way home and that was when the film trailer came to mind as a rather good analogy. I get the message, but it seems a rather odd way to go about conveying it. From a distance we are drawn to looking but then castigated for doing so. A case of look at me, why are you looking at me? And so, it seems to me that the idea behind the message is somehow diluted and even trivialised. The top is no more than a fashion item in the sense of it being a top but also in a sense of the message. The message is commercialised; I wonder whether the top was purchased because of the seriousness of the message it conveyed or because it would look good and attract attention?

I discussed this with a colleague and she brought another dimension to the discussion. Simply this, where was the top made? Quite possibly, even likely, in a sweat shop in Asia by impoverished female workers. And so, a seemingly innocent garment symbolises all the wrong things; entrapment, commercialism and inequality. I can’t help thinking on this International Women’s Day that it’s a funny old world that we live in.

We Want Equality! When do we want it?

I’ve been thinking a lot about equality recently. It is a concept bandied around all the time and after all who wouldn’t want equal life opportunities, equal status, equal justice? Whether we’re talking about gender, race, sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status. religion, sex or maternity (all protected characteristics under the Equality Act, 2010) the focus is apparently on achieving equality. But equal to what? If we’re looking for equivalence, how as a society do we decide a baseline upon which we can measure equality? Furthermore, do we all really want equality, whatever that might turn out to be?

Arguably, the creation of the ‘Welfare State’ post-WWII is one of the most concerted attempts (in the UK, at least) to lay foundations for equality.[1] The ambition of Beveridge’s (1942) Report of the Inter-Departmental Committee on Social Insurance and Allied Services was radical and expansive. Here is a clear attempt to address, what Beveridge (1942) defined as the five “Giant Evils” in society; ‘squalor, ignorance, want, idleness, and disease’. These grand plans offer the prospect of levelling the playing field, if these aims could be achieved, there would be a clear step toward ensuring equality for all. Given Beveridge’s (1942) background in economics, the focus is on numerical calculations as to the value of a pension, the cost of NHS treatment and of course, how much members of society need to contribute to maintain this. Whilst this was (and remains, even by twenty-first century standards) a radical move, Beveridge (1942) never confronts the issue of equality explicitly. Instead, he identifies a baseline, the minimum required for a human to have a reasonable quality of life. Of course, arguments continue as to what that minimum might look like in the twenty-first century. Nonetheless, this ground-breaking work means that to some degree, we have what Beveridge (1942) perceived as care ‘from cradle to grave’.

Unfortunately, this discussion does not help with my original question; equal to what? In some instances, this appears easier to answer; for example, adults over the age of 18 have suffrage, the age of sexual consent for adults in the UK is 16. But what about women’s fight for equality, how do we measure this? Equal pay legislation has not resolved the issue, government policy indicates that women disproportionately bear the negative impact of austerity. Likewise, with race equality, whether you look at education, employment or the CJS there is a continuing disproportionate negative impact on minorities. When you consider intersectionality, many of these inequalities are heaped one on top of the other. Would equality be represented by everyone’s life chances being impacted in the same way, regardless of how detrimental we know these conditions are? Would equality mean that others have to lose their privilege, or would they give it up freely?

Unfortunately, despite extensive study, I am no closer to answering these questions. If you have any ideas, let me know.

References

Beveridge, William, (1942), Report of the Inter-Departmental Committee on Social Insurance and Allied Services, (HMSO: London)

The Equality Act, 2010, (London: TSO)

[1] Similar arguments could be made in relation to Roosevelt’s “New Deal” in the USA.

The never-changing face of justice

There are occasions that I consider more fundamental questions beyond criminology, such as the nature of justice. Usually whilst reading some new sentencing guidelines or new procedures but on occasions major events such as the fire at Grenfell and the ensuing calls from former residents for accountability and of course justice! There are good reasons why contemplating the nature of justice is so important in any society especially one that has recently embarked on a constitutional discussion following the Brexit referendum.

Justice is perhaps one of the most interesting concepts in criminology; both intangible and tangible at the same time. In every day discourses we talk about the Criminal Justice System as a very precise order of organisations recognising its systemic nature or as a clear journey of events acknowledging its procedural progression. Both usually are summed up on the question I pose to students; is justice a system or a process? Of course, those who have considered this question know only too well that justice is both at different times. As a system, justice provides all those elements that make it tangible to us; a great bureaucracy that serves the delivery of justice, a network of professions (many of which are staffed by our graduates) and a structure that (seemingly) provides us all with a firm sense of equity. As a process, we identify each stage of justice as an autonomous entity, unmolested by bias, thus ensuring that all citizens are judged on the same scales. After all, lady justice is blind but fair!

This is our justice system since 1066 when the Normans brought the system we recognise today and even when, despite uprisings and revolutions such as the one that led to the 1215 signing of the Magna Carta, many facets of the system have remained quite the same. An obvious deduction from this is that the nature of justice requires stability and precedent in order to function. Tradition seems to captivate people; we only need a short journey to the local magistrates’ court to see centuries old traditions unfold. I imagine that for any time traveler, the court is probably the safest place to be, as little will seem to them to be out of place.

So far, we have been talking about justice as a tangible entity as used by professionals daily. What about the other side of justice? The intangible concept on fairness, equal opportunity and impartiality? This part is rather contentious and problematic. This is the part that people call upon when they say justice for Grenfell, justice for Stephen Lawrence, justice for Hillsborough. The people do not simply want a mechanism nor a process, but they want the reassurance that justice is not a privilege but a cornerstone of civic life. The irony here; is that the call for justice, among the people who formed popular campaigns that either led or will lead to inquiries often expose the inadequacies, failings and injustices that exist(ed) in our archaic system.

These campaigns, have made obvious something incredibly important, that justice should not simply appear to be fair, but it must be fair and most importantly, has to learn and coincide with the times. So lady justice may be blind, but she may need to come down and converse with the people that she seeks to serve, because without them she will become a fata morgana,a vision that will not satisfy its ideals nor its implementation. Then justice becomes another word devoid of meaning and substance. Thirty years to wait for an justice is an incredibly long time and this is perhaps this may be the lesson we all need to carry forward.