Home » Equality (Page 5)

Category Archives: Equality

Damned if you do, damned if you don’t: it’s a funny old world.

“Did you just look at me?” says Queen Anne to the footman and, as he shakes his head staring into oblivion clearly hoping this was not happening, she shouts “Look at me”. He reluctantly turns his head, looking at her in obvious discomfort when she screams “how dare you; close your eyes?” A short vignette from the television commercial advertising the award-winning film ‘The Favourite’ and very much a case of damned if you do and damned if you don’t for the poor hapless footman.

A few weeks ago, I accompanied my wife to a bear fair in London; she makes vintage bears as a hobby and occasionally takes to setting up a stall at some fair to sell them. As I sat behind the stall navel gazing and wandering what the football scores were, when I was going to get something to eat and when would be an appropriate time to go for a wander without giving off the vibe that enthusiasm was now waning, my wife said, ‘did you see that’? ‘What’ I asked peering over a number of furry Ursidae heads (I’m told they don’t bite)? ‘That woman in the orange top’ exclaimed my wife. Scouring the room for a woman that had been Tango’d, I listened to her explaining that a 30ish year old woman had just come out of the toilets wearing a bright orange top and emblazoned across her generous chest were the words ‘eye contact’. ‘I suppose it’s a good message’ said my wife as I settled back down to my navel gazing.

I thought about the incident, if you can call it that, on the way home and that was when the film trailer came to mind as a rather good analogy. I get the message, but it seems a rather odd way to go about conveying it. From a distance we are drawn to looking but then castigated for doing so. A case of look at me, why are you looking at me? And so, it seems to me that the idea behind the message is somehow diluted and even trivialised. The top is no more than a fashion item in the sense of it being a top but also in a sense of the message. The message is commercialised; I wonder whether the top was purchased because of the seriousness of the message it conveyed or because it would look good and attract attention?

I discussed this with a colleague and she brought another dimension to the discussion. Simply this, where was the top made? Quite possibly, even likely, in a sweat shop in Asia by impoverished female workers. And so, a seemingly innocent garment symbolises all the wrong things; entrapment, commercialism and inequality. I can’t help thinking on this International Women’s Day that it’s a funny old world that we live in.

The Bride of Frankenstein

The classic novel by Mary Shelley back in the early 19th century was an apocalyptic piece of work that imagined the future in a world where technology appeared to be a marvel that professes to make everyday people into gods. The creation of a man by a man (deliberately gendered) in accordance to his wishes, and morals. The metaphysical constraints of the soul seemingly absent, until all comes to head. This was dystopic, but at the same time philosophical, of the future of humanity.

In the 20th century John B. Watson believed that he could shape the behaviour of anyone, mostly children in any possible way. Some of his ideas even made it into popular psychology where he offered advice to parents of how to raise their children. Although no monster is mentioned, there is still the view that a man can shape a child in whatever way he chooses. A creationist and most importantly, arrogant view of the world.

Decades later Robert Martinson, a sociologist will look at all these wonderful and great programmes designed to challenge behaviours and change people, so they can rehabilitate leaving criminality behind. He found the results to be disappointing. In the meantime, child psychologists could not achieve this leap that Watson seem to think they could make in changing people.

In the 21st century we began to realise at a discipline level that forcing change upon people is rather impossible. How about a man creating a man? Can you develop a new human that will be developed espousing the creator’s desired attributes and thus become a model citizen? In recent years we have been talking about designer babies, gene harvesting and genetic modification. Such a surprising concept considering the Lebensborn experience during the Nazi regime. That super-man concept was shattered in thousands little pieces, and for many relegated to history books. Therefore, designer babies are such a cautionary tale.

As a society we are still curious on what can technology can achieve, how far can we go and what can we develop. Still in science there are seeds of creationism proposing ideas of that we can develop; a world of people without illness, disorder and deviance. Pure, healthy and potentially exceptional individuals who may be physiologically right but sadly devoid of humanity. Why devoid? Because what makes a person? Our imperfections, deviances and foibles. These add to, rather than substract from, our uniqueness and individuality.

In a recent twitter discussion one of my colleagues engaged in a discussion about the repatriation of one of those women called “Isis brides”. The colleague posed the question, why not allow her to return, only to receive in response, because these are no humans. As I read it I thought, well this is a new interpretation of the monster. A 21st century monster that we can chase out of the proverbial village with torches because its alive and it shouldn’t be. We can wish for people to be good to us, open armed and happy all the time, but that is not necessarily how it is. We know that this is the case and of course we want to be reminded of our humanity, not for the positives but for the negatives. Not what we can be but what the others are not. So, we can always be the villagers and never the monster.

Mary Shelley (1888) Frankenstein or The Modern Prometheus, London, George Routledge and Sons.

We Want Equality! When do we want it?

I’ve been thinking a lot about equality recently. It is a concept bandied around all the time and after all who wouldn’t want equal life opportunities, equal status, equal justice? Whether we’re talking about gender, race, sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status. religion, sex or maternity (all protected characteristics under the Equality Act, 2010) the focus is apparently on achieving equality. But equal to what? If we’re looking for equivalence, how as a society do we decide a baseline upon which we can measure equality? Furthermore, do we all really want equality, whatever that might turn out to be?

Arguably, the creation of the ‘Welfare State’ post-WWII is one of the most concerted attempts (in the UK, at least) to lay foundations for equality.[1] The ambition of Beveridge’s (1942) Report of the Inter-Departmental Committee on Social Insurance and Allied Services was radical and expansive. Here is a clear attempt to address, what Beveridge (1942) defined as the five “Giant Evils” in society; ‘squalor, ignorance, want, idleness, and disease’. These grand plans offer the prospect of levelling the playing field, if these aims could be achieved, there would be a clear step toward ensuring equality for all. Given Beveridge’s (1942) background in economics, the focus is on numerical calculations as to the value of a pension, the cost of NHS treatment and of course, how much members of society need to contribute to maintain this. Whilst this was (and remains, even by twenty-first century standards) a radical move, Beveridge (1942) never confronts the issue of equality explicitly. Instead, he identifies a baseline, the minimum required for a human to have a reasonable quality of life. Of course, arguments continue as to what that minimum might look like in the twenty-first century. Nonetheless, this ground-breaking work means that to some degree, we have what Beveridge (1942) perceived as care ‘from cradle to grave’.

Unfortunately, this discussion does not help with my original question; equal to what? In some instances, this appears easier to answer; for example, adults over the age of 18 have suffrage, the age of sexual consent for adults in the UK is 16. But what about women’s fight for equality, how do we measure this? Equal pay legislation has not resolved the issue, government policy indicates that women disproportionately bear the negative impact of austerity. Likewise, with race equality, whether you look at education, employment or the CJS there is a continuing disproportionate negative impact on minorities. When you consider intersectionality, many of these inequalities are heaped one on top of the other. Would equality be represented by everyone’s life chances being impacted in the same way, regardless of how detrimental we know these conditions are? Would equality mean that others have to lose their privilege, or would they give it up freely?

Unfortunately, despite extensive study, I am no closer to answering these questions. If you have any ideas, let me know.

References

Beveridge, William, (1942), Report of the Inter-Departmental Committee on Social Insurance and Allied Services, (HMSO: London)

The Equality Act, 2010, (London: TSO)

[1] Similar arguments could be made in relation to Roosevelt’s “New Deal” in the USA.

Changes in Life

When I suggested writing for this blog to certain colleagues I was told that this topic would be of no interest and nobody would read it as it is not relevant. I consider the topic very relevant to me and to every woman. The term used is ‘women of a certain age’ (I hate the expression) to explain the menopause.

I am a 55-year-old woman who is going through the menopause and I make no apologies as there is nothing I can do about it. There is acceptance of women starting their periods and the advertisements for period poverty. There are extensive adverts, promotions, books all on pregnancy but very little about the menopause. At last, just this evening, I have seen an advert by Jenny Éclair on TV about a product for one symptom of the menopause. I fail to understand why this subject is not discussed more openly?

Having reached the menopause, I can honestly say this is the worst I have ever felt both emotionally and physically. The brain fog, not being able to put a sentence together sometimes, clumsiness, the lack of sleep, loss of confidence, weight gain; aching limbs. The list goes on. I know that each woman is different, and their body responds differently so I speak for me. I know that I am not alone though just by the conversations I have with other women and on the menopause chat room.

In accepting my situation and desperately trying to work through these symptoms I reflect on an incident where my mother was arrested for shoplifting. She would have been my age at the time. I was so angry at her as I was a serving police officer and I was so embarrassed. I never tried to understand why she did it. Did the menopause contribute to the theft of cushion covers she did not need? To this day we have never spoken about the incident and never will.

Also, my thoughts around this situation extends to the research I am conducting around the treatment of transgender people in prison. Researching the prison estate, I find that the prison population is getting older and the policies link to women in prison, catering for women and babies, addictions, mental health etc but there is no mention of older women going through the menopause?

I served in the police at a time when women were not equal to men and I would never have raised, and written this blog entry exposing ‘weaknesses’. To write this is progress for me and I can even see that the police are addressing the issues of the menopause through conversations, presentations and support groups. They have come a long way. All family, friends, colleagues and employers need to try and understand this debilitating change in life for us ‘women of a certain age’.

Oh, just f*** off.

A strange title to give to a blog but, one that expresses my feelings every time I turn the television and watch politicians procrastinating about a major issue. How else do I try and express my utter contempt for the leaders of this country that cause chaos and misery and yet take no responsibility for what they have done.

I watch Donald Trump on television and I’m simply given to thinking ‘You’re an idiot’, I appreciate that others may have stronger words, particularly some immigrants, legal or illegal, in the United States. I will draw parallels with his approach later, how could I not, given the Empire Windrush disgrace.

A week or so ago a significant topic on the news was the gender pay gap. The Prime Minister Theresa May was all over this one, after all it is the fault of corporations and businesses the pay gap exists. No responsibility there then but votes to be had.

Within the same news bulletin, there was an interview with a teacher who explained how teachers were regularly taking children’s clothes home to wash them as the family couldn’t afford to do so. Children were appearing at school and the only meal they might have for the day was the school meal. Now that might seem terrible in a third world country but he wasn’t talking about a third world country he was talking about England. Surprisingly, the prime minister was not all over that one, no votes to be had.

Within the same time frame there were more deaths in London due to gang crime. The Prime Minister and the Home Secretary Amber Rudd were all over that one, well of sorts, but then it is a political hot potato. The police and the community need to do more, an action plan is produced.

Then we have the Windrush debacle, tragedy and disgrace. The Home Secretary eventually said she was sorry and blamed the civil servants in the Home Office. They had become inhuman, clearly not her fault. The Prime Minister said sorry, it was under her watch at the Home Office that the first seeds of this disaster were plotted and then hatched, clearly though not her fault either. Got the right wing votes but seem to have lost a few others along the way.

What ties all of these things together; class structure, inequality and poverty and an unwillingness in government to address these, not really a vote winner. The gender pay gap is someone else’s fault and even if addressed, won’t deal with the inequalities at the bottom of the pay structure. Those women on zero hour contracts and minimum wages won’t see the benefit, only those in middle or higher ranking jobs. Votes from some but not from others, a gain rather than any loss.

The fact that children exist in such poverty in this country that teachers have to intervene and take on welfare responsibilities is conveniently ignored. As is the fact that much of the violence that plagues the inner city streets happens to occur in poor neighbourhoods where social and economic deprivation is rife. The Windrush issue is just another example of right wing rhetoric leading to right wing action that impacts most on the vulnerable.

When the gender pay gap hit the news there was a senior figure from a company that appeared in the news. He said that addressing the gender pay gap by having more women in higher positions in his company was good for the company, good for the country, and good for the economy.

Judging from the example given by the country’s senior management, I have to say I am far from convinced. And yes as far as I’m concerned, when they open their mouths and pontificate, they can just f*** off.

‘I read the news today, oh boy’

The English army had just won the war

The English army had just won the war

A crowd of people turned away

But I just had to look

Having read the book

(Lennon and McCartney, 1967),

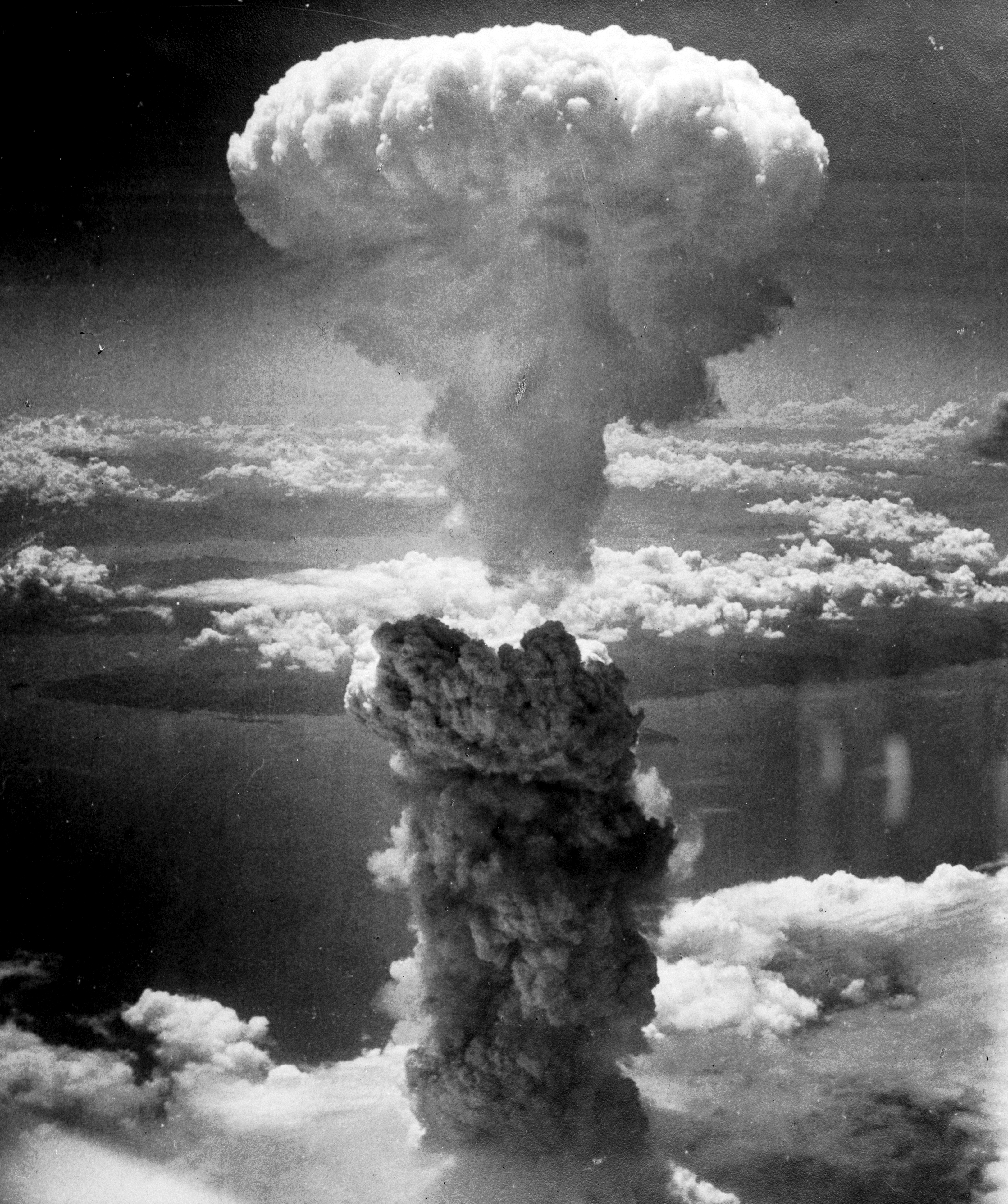

The news these days, without fail, is terrible. Wherever you look you are confronted by misery, death, destruction and terror. Regular news channels and social media bombard us with increasingly horrific tales of people living and dying under tremendous pressure, both here in the UK and elsewhere in the world. Below are just a couple of examples drawn from the mainstream media over the space of a few days, each one an example of individual or collective misery. None of them are unique and they all made the headlines in the UK.

‘Deaths of UK homeless people more than double in five years’

‘Syria: 500 Douma patients had chemical attack symptoms, reports say’

‘London 2018 BLOODBATH: Capital on a knife edge as killings SOAR to 56 in three months’

So how do we make sense of these tumultuous times? Do we turn our backs and pretend it has nothing to do with us? Can we, as Criminologists, ignore such events and say they are for other people to think about, discuss and resolve?

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, Stanley Cohen, posed a similar question; ‘How will we react to the atrocities and suffering that lie ahead?’ (2001: 287). Certainly his text States Of Denial: Knowing about Atrocities and Suffering makes clear that each of us has a part to play, firstly by ‘knowing’ that these things happen; in essence, bearing witness and acknowledging the harm inherent in such atrocities. But is this enough?

Cohen, persuasively argues, that our understanding has fundamentally changed:

The political changes of the last decade have radically altered how these issues are framed. The cold-war is over, ordinary “war” does not mean what it used to mean, nor do the terms “nationalism”, “socialism”, “welfare state”, “public order”, “security”, “victim”, “peace-keeping” and “intervention” (2001: 287).

With this in mind, shouldn’t our responses as a society, also have changed, adapted to these new discourses? I would argue, that there is very little evidence to show that this has happened; whilst problems are seemingly framed in different ways, society’s response continues to be overtly punitive. Certainly, the following responses are well rehearsed;

- “move the homeless on”

- “bomb Syria into submission”

- “increase stop and search”

- “longer/harsher prison sentences”

- “it’s your own fault for not having the correct papers?”

Of course, none of the above are new “solutions”. It is well documented throughout much of history, that moving social problems (or as we should acknowledge, people) along, just ensures that the situation continues, after all everyone needs somewhere just to be. Likewise, we have the recent experiences of invading Iraq and Afghanistan to show us (if we didn’t already know from Britain’s experiences during WWII) that you cannot bomb either people or states into submission. As criminologists, we know, only too well, the horrific impact of stop and search, incarceration and banishment and exile, on individuals, families and communities, but it seems, as a society, we do not learn from these experiences.

Yet if we were to imagine, those particular social problems in our own relationships, friendship groups, neighbourhoods and communities, would our responses be the same? Wouldn’t responses be more conciliatory, more empathetic, more helpful, more hopeful and more focused on solving problems, rather than exacerbating the situation?

Next time you read one of these news stories, ask yourself, if it was me or someone important to me that this was happening to, what would I do, how would I resolve the situation, would I be quite so punitive? Until then….

Whoever fights monsters should see to it that in the process he does not become a monster. And when you look long into an abyss, the abyss also looks into you (Nietzsche, 1886/2003: 146)

References:

Cohen, Stanley, (2001), States Of Denial: Knowing about Atrocities and Suffering, (Cambridge: Polity Press)

Lennon, John and McCartney, Paul, (1967), A Day in the Life, [LP]. Recorded by The Beatles in Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, EMI Studios: Parlaphone

Nietzsche, Friedrich, (1886/2003), Beyond Good and Evil: Prelude to a Philosophy of the Future, tr. from the German by R. J. Hollingdale, (London: Penguin Books)

You know what really grinds my gears…

Jessica is an Associate Lecturer teaching modules in the first year.

Unlike the episode from Family Guy, which sees the main character Peter Griffin present a segment on the Quahog news regarding perhaps ‘trivial’ issues which really grind his gears, I would hope that what grinds my gears is also irritating and frustrating for others.

What really grinds my gears is the portrayal of women without children being pitied in the media. Take a recent example of Jennifer Aniston who has (relatively recently) split from her partner. The coverage appears to be (and this is just my interpretation) very pitiful around how Jennifer does not have any children; and this is a shame. Is it? Has anyone bothered to ask Jennifer if she feels this is a shame? Is this something Jennifer feels is missing from her life? Who knows: It might be the case. But the issue that I have, and ultimately what really grinds my gears, is this assumption that as a woman you are expected to want and to eventually have children.

There are lots of arguments around how society is making progress (I’ll leave it amongst yourselves to argue if this is accurate or not, and if so to what extent), however is it in this context? If women are still pressured by the media, family and friends to conform to the gendered stereotype of women as mothers, has society made progress? I am not for one minute saying that women shouldn’t be mothers, or that all women should be mothers; what I am annoyed about is this apparent assumption that all women want to be mothers and more harmful, the ignorant assumption that all women can be mothers.

It really grinds my gears that it still appears to be the case that women are not ‘doing gender’ correctly if they are not mothers, or if they do not want to be mothers. Families and friends seem to assume that having a family is what everyone wants and strives to achieve, therefore not doing this results in some form of failure. How is this fair? The human body is complex (not that I have any real knowledge in this area), imagine the impact you are having on women assuming they want and will have a family, if biologically, and potentially financially, having one is difficult for them to do? Is it not rude that you are assuming that women want children because their biology allows them the potential to have them?

In answer to the last question: Yes! I think it is rude, wrong and ultimately irritating that it is assumed that all women want children and them not having them somehow means their life has missed something. As with all lifestyle choices and decisions, not every lifestyle is for everyone. Therefore I would greatly appreciate it if society acknowledged that women not wanting or having children does not mean that they have accomplished less in life in comparison to those who have children, it just means they have made different choices and walked different paths.

For me, this just highlights how far we still have to go to eradicate gender stereotypes; that is, if we even can?

Out early on good behaviour

Dr Stephen O’Brien is the Dean for the Faculty of Health and Society at the University of Northampton

The other week I had the opportunity to visit one of our local prisons with academic colleagues from our Criminology team within the Faculty of Health and Society at the University of Northampton. The prison in question is a category C closed facility and it was my very first visit to such an institution. The context for my visit was to follow up and review the work completed by students, prisoners and staff in the joint delivery of an academic module which forms part of our undergraduate Criminology course. The module entitled “Beyond Justice” explores key philosophical, social and political issues associated with the concept of justice and the journeys that individuals travel within the criminal justice system in the UK. This innovative approach to collaborative education involving the delivery of the module to students of the university and prisoners was long in its gestation. The module itself had been delivered over several weeks in the Autumn term of 2017. What was very apparent from the start of this planned visit was how successful the venture had been; ground-breaking in many respects with clear impact for all involved. Indeed, it has been way more successful than anyone could have imagined when the staff embarked on the planning process. The project is an excellent example of the University’s Changemaker agenda with its emphasis upon mobilising University assets to address real life social challenges.

My particular visit was more than a simple review and celebration of good Changemaker work well done. It was to advance the working relationship with the Prison in the signing of a memorandum of understanding which outlined further work that would be developed on the back of this successful project. This will include; future classes for university/prison students, academic advancement of prison staff, the use of prison staff expertise in the university, research and consultancy. My visit was therefore a fruitful one. In the run up to the visit I had to endure all the usual jokes one would expect. Would they let me in? More importantly would they let me out? Clearly there was an absolute need to be on my best behaviour, keep my nose clean and certainly mind my Ps and Qs especially if I was to be “released”. Despite this ribbing I approached the visit with anticipation and an open mind. To be honest I was unsure what to expect. My only previous conceptual experience of this aspect of the criminal justice system was many years ago when I was working as a mental health nurse in a traditional NHS psychiatric hospital. This was in the early 1980s with its throwback to a period of mental health care based on primarily protecting the public from the mad in society. Whilst there had been some shifts in thinking there was still a strong element of the “custodial” in the treatment and care regimen adopted. Public safety was paramount and many patients had been in the hospital for tens of years with an ensuing sense of incarceration and institutionalisation. These concepts are well described in the seminal work of Barton (1976) who described the consequences of long term incarceration as a form of neurosis; a psychiatric disorder in which a person confined for a long period in a hospital, mental hospital, or prison assumes a dependent role, passively accepts the paternalist approach of those in charge, and develops symptoms and signs associated with restricted horizons, such as increasing passivity and lack of motivation. To be fair mental health services had been transitioning slowly since the 1960s with a move from the custodial to the therapeutic. The associated strategy of rehabilitation and the decant of patients from what was an old asylum to a more community based services were well underway. In many respects the speed of this change was proving problematic with community support struggling to catch up and cope with the numbers moving out of the institutions.

My only other personal experience was when I spent a night in the cells of my local police station following an “incident” in the town centre. This was a case of being in the wrong place at the wrong time. (I know everyone says that, but in this case it is a genuine explanation). However, this did give me a sense of what being locked up felt like albeit for a few hours one night. When being shown one of the single occupancy cells at the prison those feelings came flooding back. However, the thought of being there for several months or years would have considerably more impact. The accommodation was in fact worse than I had imagined. I reflected on this afterwards in light of what can sometimes be the prevailing narrative that prison is in some way a cushy number. The roof over your head, access to a TV and a warm bed along with three square meals a day is often dressed up as a comfortable daily life. The reality of incarceration is far from this view. A few days later I watched Trevor MacDonald report from Indiana State Prison in the USA as part of ITV’s crime and punishment season. In comparison to that you could argue the UK version is comfortable but I have no doubt either experience would be, for me, an extreme challenge.

There were further echoes of my mental health experiences as I was shown the rehabilitation facilities with opportunities for prisoners to experience real world work as part of their transition back into society. I was impressed with the community engagement and the foresight of some big high street companies to get involved in retraining and education. This aspect of the visit was much better than I imagined and there is evidence that this is working. It is a strict rehabilitation regime where any poor behaviour or departure from the planned activity results in failure and loss of the opportunity. This did make me reflect on our own project and its contribution to prisoner rehabilitation. In education, success and failure are norms and the process engenders much more tolerance of what we see as mistakes along the way. The great thing about this project is the achievement of all in terms of both the learning process and outcome. Those outcomes will be celebrated later this month when we return to the prison for a special celebration event. That will be the moment not only to celebrate success but to look to the future and the further work the University and the Prison can do together. On that occasion as on this I do expect to be released early for good behaviour.

Reference

Barton, R., (1976) Institutional Neurosis: 3rd edition, Butterworth-Heinemann, London.

About a year ago, as a team we started this blog in order to relate criminological ideas into everyday life. News, events and markers on our social calendar became sources of inspiration and inquiry. Within a year, we have managed somehow to reflect on the academic cycle, some pretty heavy social issues that evoked our passions and interests. Those of you who read our entries, thank you for taking the time, especially those who left comments with your own experiences and ideas.

About a year ago, as a team we started this blog in order to relate criminological ideas into everyday life. News, events and markers on our social calendar became sources of inspiration and inquiry. Within a year, we have managed somehow to reflect on the academic cycle, some pretty heavy social issues that evoked our passions and interests. Those of you who read our entries, thank you for taking the time, especially those who left comments with your own experiences and ideas.