Home » Dissertation

Category Archives: Dissertation

Homelessness: Outsiders and Surviving on the Street: A snapshot of my undergraduate dissertation.

As the wait until graduation dissipates, I thought I may outline my dissertation and share some of the interesting notions I discovered and the events I experienced throughout the process of creating potentially the most extensive research project each of us has conquered so far.

What was my research about?

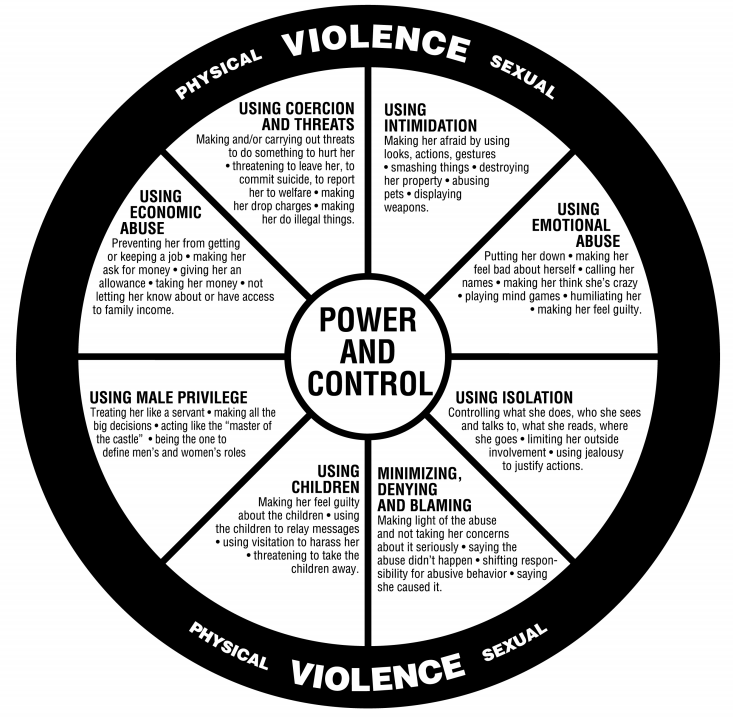

As we all know, the issue of homelessness is rife throughout the streets of Northampton and across the UK. I wanted to explore two main areas of homelessness that I understood to be important: the Victimisation of the homeless and the Criminalisation of the homeless. Prior research suggested that the homeless were victimised more frequently than the general public; they are more invisible victims, ignored and abused. There is a lack of reporting of the victimisation they face, partially explained by the lack of trust and lack of embracing victim identity, therefore, a lack of understanding of the victimisation this group faces. They are treated as outsiders, so they act as outsiders, the out-group whose behaviour is deemed ‘deviant,’ resulting in exclusionary tactics such as Hostile Architecture and legislation to hinder their ability to survive. Statistics do suggest that a large number of the homeless population have previously engaged in criminal activity, but the reasonings behind the criminality are distinct. There is an understanding that the criminal behaviour engaged in by the homeless population is survival in nature and only conducted to sustain themselves on the street. The crimes they commit may be due to the ‘criminogenic’ situation they find themselves in where they have to conduct these behaviours due to the environment, society and the economy.

What did I do?

My research was conducted in The Hope Centre, a homeless and hardship charity located in Northampton. Within the centre, I conversed with 7 service users about their experiences living on the street, engagement with criminal activity and the events they have faced. I based my research around an interpretivist lens to capture their experiences and ensure they are subjective and connected to that individual.

What did I find?

The conversations produced a multitude of different reoccurring themes, but the three I believe to be the most stand-out and important are Survival, Cynicism and Labelling, and Outsiders.

Within the survival theme, numerous individuals spoke of the criminality that they have engaged in whilst being on the street, from shoplifting to drug dealing. Still, there was a variety of different justifications used to rationalise their behaviour. Some individuals explained that the crime was to be able to sustain themselves, eat, sleep, etc. For some, the criminality was rationalised by softening the victim’s stance by suggesting they were faceless or victimless if they targeted large corporations. For some, the rationale was to purchase drugs, which, although deemed a commodity and a luxury by some, is also a necessity by others, needing a particular substance to be able to live through the night.

Within the Cyclicism theme, a common topic was that of the society that these individuals reside in; the homeless that have sometimes been released from prison are let out into a society with a lack of job opportunities (due to criminal records) and a drug culture that forces them into other money-making ventures such as criminality, resulting in a total loop back into the prison system. Some participants were under the assumption that the prison system was designed this way to create money by pushing them back into it.

One final theme was that of labelling and outsiders, this is the situation whereby individuals the participants were perceived negatively regardless of what they did and how they acted. They suggested that they were seen as ‘dirty’ even if they had showered. Due to this, they were excluded from society for being an outlier and seen as different to the ‘in-group’ with no control over changing that. This led to some participants attempting to change their behaviour and look to fit in with societal norms. There is also a perception from the homeless about other homeless individuals, specifically the divide between those who beg and those who do not. Some believe that those who beg, harass people and give the entire community a ‘bad rep.’

My dissertation did not aim to drive a specific conclusion due to the individual nature of the conversations. However, it is my hope and aim to potentially change the perceptions and actions of each individual who has read my dissertation regarding this neglected group in society.

What’s stopping us from rehabilitating mentally ill offenders?

I wanted to share with you some key takeaways from the findings of my dissertation; “Understanding Positive Risk-Taking and Barriers to Implementation in Forensic Mental Health.”

For context, positive risk taking is the process of supporting recovery and rehabilitation by actively and carefully engaging service users in decisions and activities that have previously posed a risk, in full acknowledgement of that risk, in the hope it has a positive outcome and builds new skills.

My thematic structure from 5 interviews with forensic healthcare professionals is below for reference.

| Theme | Subtheme |

| Engaging the Service User | – Offering, Accepting, Assessing – Staffing Safe Opportunities |

| Professional Development and Confidence in Practice | – Specialised Training and Professional Development – Confidence in Practice and Taking Responsibility – Challenging Anti-Progressive Attitudes |

| Navigating the Unique Needs of the Service User Group | – Acknowledging and Communicating Risk – Severe, Enduring and Fluctuating Conditions – Stuck in the System – The Juxtaposition of Justice |

Engaging the service user is around the safe engagement of the service user within this process:

- Service users are not being engaged in their own risk assessment which would allow them to build up skills in identifying and managing their own risk.

- Seclusion is being used for more ‘difficult’ to manage service users to compensate for low staffing which is detrimental to service user progress and a huge ethical problem.

Professional Development and Confidence in Practice discussed the complexities of training to work in forensic care and the fear around being responsible for decisions that could go very wrong.

- My participants expressed concerns that primarily clinical practitioners (i.e. clinical psychologists over forensic psychologists) may not be able to work as sufficiently with forensic clients as their training backgrounds and treatment models may favour either the judicial process or the therapeutic outcome, and whilst both are needed, it is unlikely to be available.

- Healthcare professionals also battle with colleagues who are not on board with the approach of offering positive risks, sometimes due to fear, others to not believing that the experience should positive due to the reasons a person is there.

Navigating the Unique Needs of the Service User Group discusses the nuances of forensics and what makes this service different to others.

- It is identified that some professionals find it more difficult to engage in and justify positive risks when it involves certain (overrepresented) conditions, such as psychosis, and certain offenses (sexual), particularly if there are vulnerable victims, which may impact treatment opportunities regardless of other ‘good’ factors.

- Information handed over from the criminal justice system to healthcare system is often dehumanising, reductionist and causes exaggerated risk levels which increases fear and safety behaviours from healthcare staff.

- Service users are subject to the conditions and restrictions of both the healthcare services and the criminal justice system which can present conflicting interests and outcomes from each institution. Additionally, the decisions made by the criminal justice system are often done so despite caseworkers never having met or worked directly with the service user, inhibiting healthcare professionals from using their professional judgement to offer positive risk-taking opportunities.

- Service users are very often ‘in the system’ for a long time, so much so that they may begin to fear life outside of an institution and may sabotage their own progress in order to stay within a familiar institution and possibly even to go back to prison.

Much more needs to be done, and needs to change to improve this increasingly prevalent service. It is my hope that more research within this area will help to support the recovery and rehabilitation of those who are cared for in forensic mental health settings and that my findings might inspire anyone who goes on to work with mentally ill offenders to make improvements to what they find in their workplace. Whilst my study was primarily within the secure healthcare space, much is transferrable to other areas of the criminal justice system.

Zemiological Perspective: Educational Experiences of Black Students at the University of Northampton

As a young Black female who has faced many challenges within the education system, particularly related to behavioral issues, I noticed how the system can unintentionally harm black students. I observed that Black children’s experiences in the education system are not always viewed from a deviant perspective, because they are not inherently deviant. The institutional harm faced by Black students is not always a ‘crime’ nor is it illegal, yet it is profoundly damaging.

This realisation prompted me to adopt a zemiological perspective, drawing upon the work of Hillyard et al. (2004) to highlight the subtle yet impactful harms faced by Black students in the educational system. My primary objective was to uncover the challenges these students face, as outlined in my initial research question: ‘To what extent can the experiences of Black students in higher education be understood as a form of social harm?’ To achieve this, I analysed the educational experiences of Black students at the University of Northampton. This involved reviewing the university’s access and participation plans, which detail the performance, access, and progression of various demographics within the institution, with a particular focus on BAME students.

Critical race theory (CRT) was the guiding theoretical framework for this research study. CRT recognises the multifaceted nature of racism, encompassing both blatant acts of racial discrimination and subtler, systemic forms of oppression that negatively impact minority ethnic groups (Gillborn, 2006). This theoretical approach is directly correlated to my research and was strongly relevant. This allowed me to gain insight into the underlying reasons behind the disparities faced by Black students in higher education. As well as enabling me to unpack the complexities of racism and discrimination, providing a comprehensive understanding of how these issues manifest and persist within the educational landscape.

Through conducting content analysis on the UON Access and Participation Plan document and comparing it to sector averages in higher education, four major findings came to light:

Access and Recruitment: The University of Northampton has made impressive progress in improving access and recruitment for BAME students, fostering diversity and inclusivity in higher education, and surpassing sector standards. Yet, while advancements are apparent, there remains a need for more comprehensive approaches to tackle systemic barriers and facilitate academic success across the broader sector.

Non-Continuation: Alarmingly, non-continuation rates among BAME students at the University of Northampton have surpassed the sector average, indicating persistent systemic obstacles within the education system. High non-continuation rates perpetuate cycles of disadvantage and limit opportunities for personal and professional growth.

Attainment Gap: Disparities in academic attainment between White and BAME students have persisted and continue to persist, reflecting systemic inequalities and biases within the academic landscape. UON is significantly behind the sector average when it comes to attainment gaps between BAME students and their white counterparts. Addressing the attainment gap requires comprehensive approaches that tackle systemic difficulties and provide targeted support to BAME students.

Progression to Employment or Further Study: UON is also behind the sector average in BAME students progression in education or further study. BAME students face substantial disparities in progression to employment or further study, highlighting the need for collaborative efforts to promote diversity and inclusivity within industries and professions. Addressing entrenched biases in recruitment processes is essential to fostering equitable opportunities for BAME students.

Contributions to Research: This research deepens understanding of obstacles within the educational system, highlighting the effectiveness of a zemiological perspective in studying social inequalities in education. By applying Critical Race Theory, the study offers insights that can inform policies aimed at fostering equity and inclusion for Black students.

The findings hold practical implications for policy and practice, informing the development of interventions to address disparities and create a more supportive educational environment. This research significantly contributes to our understanding of the experiences of Black students in higher education and provides valuable guidance for future research and practice in the field.

Aside from other limitations in my dissertation, the main limitation was the frequent use of the term ‘BAME.’ This term is problematic as it fails to recognise the distinct experiences, challenges, and identities of individual ethnic communities, leading to generalisation and overlooking specific issues faced by Black students (Milner and Jumbe, 2020). While ‘BAME’ is used for its wide recognition in delineating systemic marginalisation (UUK 2016 cited in McDuff et al., 2018), it may conceal the unique challenges Black students face when grouped with other minority ethnic groups. The term was only used throughout this dissertation as the document being analysed also used the term ‘BAME’.

This dissertation was a very challenging but interesting experience for me, engaging with literature was honestly challenging but the content in said literature did keep me intrigued. Moving forward, i would love Black students experiences to continue to be brought to light and i would love necessary policies, institutional practises and research to allow change for these students. I do wish i was more critical of the education system as the harm does more so stem from institutional practices. I also wish i used necessary literature to highlight how covid-19 has impacted the experiences of black students, which was also feedback highlighted by my supervisor Dr Paula Bowles.

I am proud of myself and my work, and i do hope it can also be used to pave the way for action to be taken by universities and across the education system. Drawing upon the works of scholars like Coard, Gillborn, Arday and many others i am happy to have contributed to this field of research pertaining to black students experiences in academia. Collective efforts can pave the way for a more promising and fairer future for Black students in education.

References

Gillborn, D. (2006). Critical Race Theory and Education: Racism and anti-racism in educational theory and praxis. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 27 (1), 11–32. [Accessed 21 April 2024]

Hillyard, P., Pantazis, C., Tombs, S. and Gordon, D., (Eds), (2004). Beyond Criminology: Taking Harm Seriously, London: Pluto Press.

Milner, A. and Jumbe, S., (2020). Using the right words to address racial disparities in COVID-19. The Lancet Public Health, 5(8), pp. e419-e420

Mcduff, N., Tatam, J., Beacock, O. and Ross, F., (2018). Closing the attainment gap for students from Black and minority ethnic backgrounds through institutional change. Widening Participation and Lifelong Learning, 20(1), pp.79-101.

Auschwitz – secrets of the ground

Indifference is not a beginning; it is an end. And, therefore, indifference is always a friend to the enemy, for it benefits the aggressor – never his victim

Elie Wiesel

I have been fortunate enough in my life to have been able to live and travel abroad, a luxury you should never take for granted. Having traveled in every continent there are plenty of things I will never forget, mostly good but one thing that will stay with me will be Auschwitz. It is hard to get excited about visiting Auschwitz, but it is also hard to not get excited about visiting Auschwitz. The day I visited Auschwitz, on the journey there a flurry of strange thoughts went through my head, perhaps ones you would only have when attending a funeral where you are supposed to be in grief. What do you wear, should I smile, what do you talk about, essentially you are creating a rule book inside your head of how not to be offensive. It’s a strange thought process and perhaps completely irrational, one of which I will probably never go through again. If I had to describe Auschwitz in one word, that word would be haunting and I could write for hours about Auschwitz without ever being able to get across the feeling of visiting it, but instead, I am going to share with you a poem I wrote on the journey back from Auschwitz, this poem has never seen the light of day and has been in my diary for over a decade, until now, but it feels like a perfect time to finally share, it’s called secrets of the ground.

Dark skies and tearful eyes,

only God knows the secrets this ground hides.

The flowers mask the crimes of old,

the walls are chipped by bullet holes.

Haunting sounds drowned out by hymns,

the shoes of children too scared to blink.

A cold wind howls in these Polish fields,

one million people how can this be real.

A train stands alone on the blackened track,

barb wire fences to hold them back.

The secrets out, the grounds have spoken,

we must never forget the lives that were taken.

Holocaust Memorial Day: 27th January

The 27th January marks an important event, Holocaust Memorial Day. This is a day to remember those who were murdered by the cruel Nazi regime, including 6 million Jews. These people were subject to the worst treatment that the modern world has ever seen. The Holocaust reminds us of how dangerous humankind can be to one another. These Nazi men went to work each morning knowing what they were doing and going home to their family at the end of their day of murders. This is something that I cannot comprehend, people that were so truly evil to degrade a whole group of people just because of who they are.

As someone who has had the opportunity to visit Auschwitz on an education trip while at school, I can say that the place is like nothing I could have ever imagined. The vast size and scale of both camps was inconceivable. To be in a place where so many people suffered their worst pains and lost their lives, it was a harrowing experience. From the hair to the scratch marks on the gas chamber walls, the place felt like no other. There was an uncomfortable feeling when you enter the gates of Arbeit macht frei, meaning, work will set you free. To know that so many walked under these gates not knowing what their fate held. And all of this for the Jews was because of their religion and the threat Hitler perceived them to have on Germany.

This is a topic that has always interested me, questioning why the Jewish community? My dissertation research so far has shown how the Jews were scapegoated by the Nazis for their successful businesses in and around Germany. Many Jewish families owned banks, jewellers and local businesses. The Nazis used this peaceful group of people and turned them into the enemy of the Nazi regime. The Jewish community was seen as a financial threat to the Nazis and needed to be eradicated for Nazi German to be successful. The hatred of the Jews developed, bringing in more dated views of the Jewish community. Within Nazi Germany, they were treated like filth and seen as subhuman because of their ‘impure’ genetics. Anyone seen to be from Jewish decent was seen as dirty and an unwanted member of society.

The stereotypes that the Jews are rich continued even after the war and still to this day, along with the stereotypes that Jews are the evil of society. Since March 2020, there have been conspiracy theories circulating on social media that the Jewish community was behind the COVID 19 pandemic. Many are suggesting that the Jewish people are trying to gain financially from the pandemic and destroy the economy. This is not something that is new, the Jewish community has faced these prejudices for as long as time.

My dissertation incorporates a study on social media and archival research. This project has taken me to the Searchlight Archives, located at the University of Northampton. The information held here shows how Britain’s far right movements carried on their anti-Semitic hate after the end of WWII. It’s very interesting to find that antisemitism never went away and still has not. Recently, the Texas Synagogue hostage crisis has show how much anti-Semitic hate is still in society. Three days after the Texas crisis, there was no longer headline news about it and those tweeting about it were part of the Jewish community.

Does this suggest that social media is anti-Semitic? Or is anti-Semitic hate not shared on social media because it is not of interest to people? Either way, Jews are still treated horribly in society and seen as a subhuman by many. This is the sad truth of antisemitism today, and this needs to change.

‘White Women, Race Matters’: Fantasies of a White Nation

Chapter II: Moving Mad in these Streets

This post in-part takes its name from a book by the late Whiteness Studies academic Ruth Frankenberg (1993) and is the second of three that will discuss Whiteness, women, and racism.

If you grew up racialised outside of Whiteness in Britain or really any Anglo-European country, the chances are you will be asked “where are you from?” on a regular basis. After reading some poems on this very issue at a Northamptonshire arts and heritage festival, I was walking home only to be stopped in my tracks by a White woman probably in her late 40s / early 50s saying “people like you aren’t really British.” Whilst I have been asking myself similar questions, for a White person to do this so confidently is unsettling … they’re moving mad in these streets. In this blog post, I will discuss this racial micro-aggression, underpinned by racist epistemologies with us Black people viewed in this country as immigrant; interloper; Other, whilst simultaneously Whiteness being synonymous with “localness” (Brown, 2006). In this encounter just outside of Northampton, I was further reminded that to be Black and British in this country is to live in a perpetual state of “double consciousness” (DuBois, 1903: 1).

Rather than identify with “Black Britishness”, (a pigeon-hole in my opinion), the term ‘afropean’ (Philips, 1987; Pitts, 2020) feels much more appropriate and fluid. However, the term Karen is one I don’t particular enjoy, but the woman in question could be described as such. In using this label, I am trying to create a frame of reference for you (the audience), not allow the person in question to escape scrutiny. This woman was a Jane Bloggs, I had never seen her before and she felt entitled enough to stop me in the street and continually criticise my right to belong. For those of you local to Northampton, I was walking between that stretch of path on Wellingborough Road, between Weston Favell Centre and Aldi. This encounter reminded me of my place in Britain, where ‘British-Asianness’ (Shukla, 2016; Riz Ahmed, 2019; Shukla, 2021) and ‘Black Britishness’ have frequently been difficult to define (Rich 1986, Gilroy, 1987; Yeboah, 1988; Young, 1995; Christian, 2008; Olusoga, 2016; Hirsch, 2017, Ventour, 2020). Even amongst White subjects themselves, what it means to be British has often been a question of challenge (Fox, 2014), and when I articulated that both my parents were born in the UK (Lichfield City and Northampton), she was visiblely upset and put-out.

The term ‘Karen’ comes from a name that was frequent among middle-aged women who were born between 1957 and 1966 with its peak in 1965 (Social Security Data). The name is also the Danish rendition of Katherine associated with the Greek for pure. Yet, the meaning of the word has undergone pejoration. In sociolinguistics, ‘pejoration’ is when a positive word becomes negative over time. ‘Karen’ as it has come to be known today has uses as early as September 2016 and as we know now, Karen has become synonymous with racist middle-aged White women, often associated with their harrassment of Black people just minding their business. On my way home, this harrassment found me walking while Black. For others, it has occured shopping while Black; birdwatching while Black; jogging while Black; listening to music in their house while Black, and more. The encounters we know about are generally examples that make news headlines but there are far more examples that do not make the national press, because they are pervasive.

Writing my MA dissertation on the 1919 Race Riots, I saw even in Edwardian Britain the nationality and citizenship rights of Black people in this country were contested (Belchem, 2014: 56), both those born British subjects in parts of the British Empire and those that were in fact born and raised here (May and Cohen, 1974), in spite of their legal status under the 1914 British Nationality and Aliens Act. Today, we are asked “where you from?” underpinned by historical racist epistemologies that defined Englishness as White (Dabiri, 2021). However, even in the image of so-called multiculturalism in the UK, the Britishness of Black and Brown people still has qualifiers attached. Watching ‘Homecoming’, the finale of David Olusoga’s popular series Black and British, the historian claims “… there is one barrier that confronted the Windrush Generation that we have largely overcome, and that’s because there are few people these days who question the idea that it is possible to be both Black and British” (54:46-55:00).

My experiences as a child and as an adult still tell me that Black Britishness is an increasingly contentious question, but even more testing … to be Black and English. In August 2021, MP David Lammy defended his right to call himself Black English from a caller into his LBC show. Whilst he was later met with lots of support online, what is interesting was the numbers of Black people on Twitter that challenged him on his right to be Black and English. If English is a nationality, better yet, a “civic identity”, nobody should be argueing someone’s right to choose where they belong. Furthermore, David Olusoga’s comments in ‘Homecoming’ seem blinkered and out of touch with people on the ground that still experience this epistemic racism on a daily basis. Especially my generation navigating the superhighways of identity where as one scholar writes, “The BBC had a whole series dedicated to ‘Black Britishness’ [Olusoga’s], which essentially amounted to propaganda for the idea that we are now accepted as part of the nation …” (Andrews, 2019: xiii).

My encounter with the woman on the street is one more example of racial privilege knowing full well that her Whiteness protected her from repercussions. Furthermore, whilst the ‘Karen’ meme started as a commentary on racial privilege (Williams, 2020) and White women in histories of racism (Ware, 1992), it’s a shame that is has been co-opted by people as a catch-all term for any woman that happens to annoy them. I think my encounter is certainly definable under the remits of the original Karen mythology, but there are those out there who would also argue my thoughts as misogynistic, namely because of what the mythology has become. In the UK, this mythology is “more proof the internet speaks American” (Lewis, 2020). And how Black Lives Matter is still spoken about is a reminder of the divides between anti-Blackness in the US and anti-Blackness in Britain. Yet, discourses on “Karen spotting” online also speak an American voice even though equivalents exist in Britain – especially in schools, colleges / universities and healthcare.

Those interested in the cultures of Black and Brown people; it would be more useful to ask about heritage over the racist “where are you from?”, as for me at least the latter is underpinned by racist binaries that say POCs cannot relate to ‘Anglo-Europeanness’, whilst the former speaks to the fluidity of an individual’s relationship with Home.

References

Andrews, K (2019) Back to Black: Retelling Black Radicalism for the 21st Century. London: ZED Books.

Belchem, J (2014) Before the Windrush: Race Relations in 20th Century Liverpool. Liverpool: University Press.

Black and British (2016) Episode 4: Homecoming [BBC iPlayer]. London: BBC 2.

Brown, J.N. (2006) Dropping Anchor Setting Sail: Geographies of Race in Black Liverpool. NJ: Princeton University Press.

Christian, M. (2008) The Fletcher Report 1930: A Historical Case Study of Contested Black Mixed Heritage Britishness. Journal of HIstorical Sociology, 21(2-3), pp. 213-241.

Dabiri, E. (2021) What White People Can Do Next: From Allyship to Coalition. London: Penguin.

DuBois, W.E.B. (1903) The Souls of Black Folk. New York: Dover Thrift.

Fox, K. (2014) Watching the English: the hidden rules of English behaviour. London: Hodder & Stoughton.

Frankenberg, R. (1993) White Women, Race Matters: The Social Construction of Whiteness. MI: UoM Press.

Gilroy, P. (1987) There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack. London: Routledge.

Hirsch, A. (2017) Brit(ish). London: Jonathan Cape.

Lewis, H. (2020) The Mythology of Karen. The Atlantic.

May, R and Cohen, R. (1974) The Interaction Between Race and Colonialism: A Case Study of the Liverpool Race Riots of 1919. Race and Class. 16(2), pp. 111-126.

Olusoga, D. (2017) Black and British: A Forgotten History. London: Pan.

Philips, C. (1987) The European Tribe. London: Faber & Faber.

Pitts, J. (2020) Afropean: Notes from Black Europe. London: Penguin.

Rich, P.B. (1986) Race and Empire in British Politics, Cambridge: Cambridge University.

Riz Ahmed (2019) Where You From? YouTube.

Shukla, N. (2016) The Good Immigrant. London: Unbound

— (2021). Brown Baby: A Memoir of Race, Family, and Home. London: Pan.

Social Security. Top 5 Names in Each of the Last 100 Years.

Ventour, T. (2020) Where Are You From? (For ‘Effing Swings & Roundabouts’ by Lauren D’Alessandro-Heath). Medium.

Ware, V. (1992) Beyond the Pale: White Women, Racism and History. London: Verso.

Williams, A. (2020) Black Memes Matter: #LivingWhileBlack With Becky and Karen. Social Media + Society. 6(4), pp. 1-14.

Yeboah, S.K. (1988) The Ideology of Racism, London: Hansib.

Young, R.J.C. (1995) Colonial Desire: Hybridity in Theory, Culture and Race, London: Routledge.

Domestic Abuse Misinterpreted: Beyond the Scope of Violence

Background

The framework behind my dissertation arose from a lifelong unanswered question in my mind: “why is psychological and emotional abuse often overlooked in domestic abuse scenarios?” This question had formed in my precocious mind as a child, this was due to experiencing domestic abuse in the family home for many years and in many forms.

Early Stages of the Dissertation

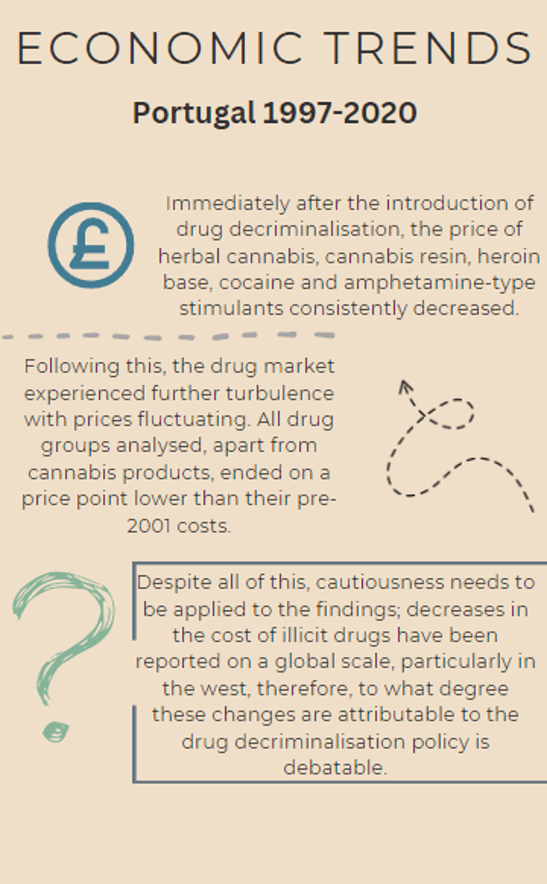

It was only when I began studying criminology at university that I unearthed many underlying questions relating to the abuse I suffered as a child and from watching my mother be psychically and mentally abused. I was understanding my experiences from an academic standpoint, as well as my peers’ experience of domestic abuse too. As a child, I had recognised that the verbal and psychological abuse was increasingly more detrimental on the victim’s mental wellbeing than the physical violence; the physical violence is a tactic used by abusers to install fear in the victim. In the early stages of my dissertation, I was gathering literature to aid my understanding on domestic abuse. I came across two essential books, one book was recommended by @paulaabowles, my dissertation supervisor: Scream Quietly or the Neighbours Will Hear (1979) by Erin Pizzey. This book provided great insight to the many aspects of domestic abuse from the memoires of Erin Pizzey who founded the first domestic abuse refugee in London 1971 known as, Chiswick Women’s Aid. The second book was: Education Groups for Men Who Batter: The Duluth Model (1993) by Pence and Paymar. This book aided my knowledge on the management of male abusers and how their abusive behaviour is explained by the using the visual theoretical framework known as, the Duluth Model; the Power and Control Wheel. I gathered more literature on domestic abuse and formed the backbone for my dissertation, it was time to self-reflect and establish my standpoint so that I could conduct my research as effectively and ethically.

The Research

This was the most important aspect of the dissertation; the most influential too. In my second-year studies, we were required to conduct research in a criminal justice agency to form a placement report; I chose a charitable organisation based in Northampton that provided support to female victims and offenders in the criminal justice system. For my dissertation, I chose to go back to the facility to conduct further research, this time my focus was on the detrimental effects experienced by female victims of domestic abuse.

Using a feminist standpoint alongside an autoethnographic method/ methodology, I was able to conduct primary research together with the participants of the study. I chose feminism as my standpoint due to the fundamental theoretical question centred in the social phenomenon of domestic abuse: gender inequality. I believe the feminist perspective was the most compatible and reliable standpoint to tackle my research with, it allowed room for self-reflection to identify my own biases and to recognise societal influences on how I interpret experiences and emotions. The standpoint’s counterpart – autoethnography – was employed so that I could actively insert myself into the research; this was supported by my research tool of observation participation and by recording qualitative data in a research diary. Over the course of nine weeks, I had formed trustworthy and respectful relationships with the participants, I had also encountered epiphanies and clarities regarding my own experiences of domestic abuse. Through using the research method observation participation, I was able to observe the body language and facial expressions of the participants alongside witnessing their emotions and participating in conversation. Collectively, my research methods enabled me to gather in-depth, first-hand accounts of the women’s experiences of domestic abuse. When writing the conclusion for my dissertation, I was able to establish that psychological and emotional abuse can be more detrimental to the victim than the physical violence itself. Interestingly, I had identified patterns and trends in the abuser’s behaviour and how it impacts the victim’s response; the victims tend to mimic their abusive partners traits e.g. anger and guilt.

I was able to conclude my dissertation with supporting evidence to credit my original question, through using personal experience and the experience of the wonderful women that participated in my research. Many of the women’s experiences highlighted in my dissertation research corresponded with the Duluth Model thesis embedded in my literature review. I was able to demonstrate how the elements of power and control in the abusive partner behaviour can adversely affect the victim; consequences of mental health issues, substance misuse and changes in victim’s lifestyle and behaviour. Overall, the experience was incredibly insightful and provided me with transferable interpersonal and analytical skills.