Home » Discrimination (Page 5)

Category Archives: Discrimination

The Euthanasia of the Youth in Asia: Milky White Skin #BlackenAsiawithLove

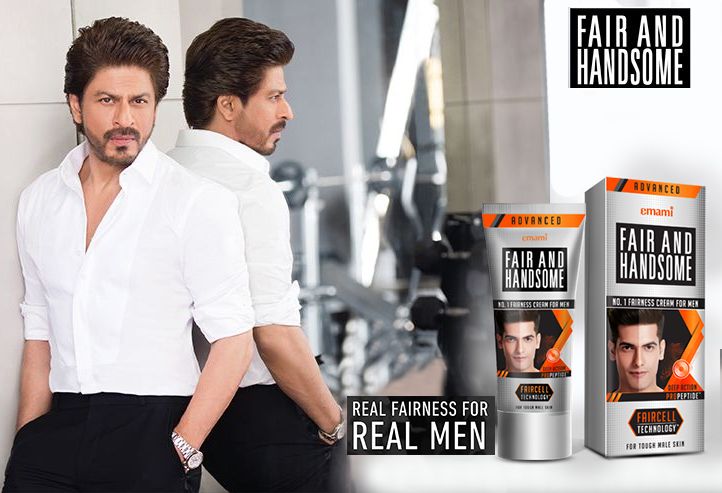

Shahrukh Khan (SRK) is arguably the Indian film industry’s biggest global star and commercial brand ambassador. In one early advertisement, he strikes a match from a dark-skinned kid’s face to show just how abhorrent it is as a trait. In another ad, ostensibly more humorous, SRK disses a group of traditional Northern Indian wrestlers for wearing skirts and make-up. The star chides them for using the feminine product instead of (converting to) the newly available male version (i.e. re-packaged in gray rather than pink). The product? The skin bleach Fair and Handsome. In both ads, the transformed, ‘fairer’ skinned consumer is pummeled with young girls virtually appearing from nowhere.

This follows the ty pical consumerist trope: The product makes users more popular and sexually appealing. Yet, things got worse. Clean and Dry’s ‘intimate’ bleaching shower gel for women (C&D). Yes, you read right: A bleaching shower gel aimed at lightening brown women’s crotches. There’s no male equivalent, save for a well-circulated spoof called Gore Gote: India’s #1 Testicular Fairness Cream (Mukherjee). In the initial shot of the C&D advertisement, a pouty-mouthed (fair-skinned) woman is ignored by her (fair-skinned) husband in their (upper-middle-class) apartment. Naturally, it seems, she bleaches her labia with C&D. After displaying the product’s virtues, the husband literally chases the wife around the fancy flat as she playfully dangles (his) keys. Her secret to happiness: A newly bleached intimate area. Is this a proxy for a white woman’s vagina?

pical consumerist trope: The product makes users more popular and sexually appealing. Yet, things got worse. Clean and Dry’s ‘intimate’ bleaching shower gel for women (C&D). Yes, you read right: A bleaching shower gel aimed at lightening brown women’s crotches. There’s no male equivalent, save for a well-circulated spoof called Gore Gote: India’s #1 Testicular Fairness Cream (Mukherjee). In the initial shot of the C&D advertisement, a pouty-mouthed (fair-skinned) woman is ignored by her (fair-skinned) husband in their (upper-middle-class) apartment. Naturally, it seems, she bleaches her labia with C&D. After displaying the product’s virtues, the husband literally chases the wife around the fancy flat as she playfully dangles (his) keys. Her secret to happiness: A newly bleached intimate area. Is this a proxy for a white woman’s vagina?

What’s wrong with consumerism? The marketplace will not save you. As a Black person interested in self-love, it is clear that the market is murderous. There, the fetish of blackness is made widely available, as if one could bottle stereotypical ‘coolness’ and sell it to the youth in Asia, one of the largest consumer groups in the world. Fashion shops targeting youth regularly plaster posters of Bob Marley or Hip-Hop thugs to peddle goods to youth. Yet, standing in the rotunda of this mall, one could see shops of every major western cosmetics brand, including Clinique, Mac, Estée Lauder. Here in Asia, the flagship product in each shop is skin bleach! Black is cool, but white is power. Ironically, at the time I was modeling for a campaign in Vogue and Elle Décor in India, yet none of the make-up artists carried my mocha shade (shady, right).

YELLOW FEVER

The skin bleach industry is by far the most virulent of all consumer products – even fast food. The bulk of this industry is meted out on the bodies of women…and girls who learn early that fate of darkness (just check out any Indian Matrimonials page). According to an August 2019 article in Vogue: “Per a recent World Health Organization report (WHO), half of the population in Korea, Malaysia, and the Philippines uses some kind of skin lightening treatment. And it’s even higher in India (60%) and African countries, such as Nigeria (77%).” After a 7 minutes instrumental intro to his 1976 hit, Yellow Fever, Fela Kuti chants: “Who steal your bleaching?/Your precious bleaching?…/Your face go yellow/Your yansh go show/Your mustache go show/Your skin go scatter/You go die o.”

The skin bleach industry is by far the most virulent of all consumer products – even fast food. The bulk of this industry is meted out on the bodies of women…and girls who learn early that fate of darkness (just check out any Indian Matrimonials page). According to an August 2019 article in Vogue: “Per a recent World Health Organization report (WHO), half of the population in Korea, Malaysia, and the Philippines uses some kind of skin lightening treatment. And it’s even higher in India (60%) and African countries, such as Nigeria (77%).” After a 7 minutes instrumental intro to his 1976 hit, Yellow Fever, Fela Kuti chants: “Who steal your bleaching?/Your precious bleaching?…/Your face go yellow/Your yansh go show/Your mustache go show/Your skin go scatter/You go die o.”

It’s lethal, often a mercurous poison used to kill the soul. It is a fetishization of whiteness, that reveals the “internalization of the coloniser’s inferiorisation of dark skin as native and Other” (Thapan: 73). It’s euthanasia. Skin bleachers are painlessly killing themselves, willingly participating in their own annihilation. Not only does it quite literally murder the melanin in one’s skin, it symbolically kills one’s ‘dark and native’ self, giving birth to a new and improved modern identity. It requires constant application and reflects a consumerist’s self-regulation. Bleach is expensive, despite the industry’s ‘bottom of the pyramid’ approach to the marketing 4P’s – bleach sold in cheap tiny packages for the poor. Skin bleach is a form of mimesis, to actually embody modernity through crafting the ‘cultivated, developed and perfected’ self (Thapan: 70).

When I began teaching at UoN, I was asked to propose topics for business ethics modules, which were then optional. Hesitantly, I suggested skin bleach and hair weaves. Looking at the composition of the student body, this would be as familiar to them, as the products were locally available (see picture below taken in an ‘ethnic’ hair shop on Northampton’s high street). Several students have subsequently pursed these subjects in their dissertations. I was sad to learn that in colloquial Somali, ‘fair skin’ is a moniker for pretty, just as we western Blacks use ‘light skin and long hair’. Colourism makes dark-skinned people unsafe in our own homes.

I was pleasantly surprised at the support from the module leader, an older, straight white man. He said he knew little about the politics of black and brown skin and hair, yet listened with great interest and did his own research into the matter. What’s more, he stood by me both literally and figuratively. He was there when I was called to account for some negative student feedback such as “I’m a guy, I don’t wear make-up,” when asked to consider the differential impact of beauty standards on the psyches and earnings of women in business. He stood by me when I’d dropped the F-word (feminism) into the curriculum. This was before the Gender Pay Gap became more widely known or theBritish government required audits from large organisations. He is an ally. He stood by me in ways that may have been riskier for individuals outside the circles of normative power of gender, race and class. Talk about a way to use one’s privilege!

References

Kuti, F. (1976). Yellow Fever. [LP] Decca 8 Track Studios. Available at: https://genius.com/Fela-kuti-and-africa-70-yellow-fever-annotated [Accessed 13 Nov. 2019].

Mukherjee, R., Banet-Weiser, S. and Gray, H. (2019). Racism Postrace. Durham, N.C.

Thapan, M. (2009). Living the Body: Embodiment, Womanhood and Identity in Contemporary India. New Delhi: SAGE.

100% of the emotional labour, 0% of the emotional reward: #BlackenAsiawithLove

Last night over dinner and drinks, I spoke about race in the classroom with two white, upper-middle-class gay educators. Neither seemed (able) to make any discernable effort to understand any perspective outside their own. I had to do 100% of the emotional labour, and got 0% of the emotional reward. It was very sad how they went on the attack, using both passive and active aggression, yet had the nerve to dismiss my words as ‘victimhood discourse’. This is exactly why folks write books, articles, and blogs like ‘Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race’.

Worse, they both had experienced homophobia in the classroom, at the hands of both students and parents. Nonetheless, they had no ability to contribute to the emotional labour taking place as we spoke about race. Even worse, the one in charge of other educators had only 24 hours earlier performed the classic micro-aggression against me: The brown blur. He walked right past me at our initial meeting as I extended my hand introducing myself while mentioning the mutual friend who’d connected us because, as he said, he was “expecting” to see a white face. He was the one to raise that incident, yet literally threw his hands in the air, nodding his head dismissively as he refused any responsibility for the potential harm caused.

“I’m an adult,” I pled, explaining the difference between me facing those sorts of aggressions, versus the young people we all educate. This all fell on deaf ears. Even worse still, he’d only moments earlier asked me to help him understand why the only Black kid in one of his classes called himself a “real nigger.” Before that, he had asked me to comment on removing the N-word from historical texts used in the classroom, similar to the 2011 debate about erasing the N-word and “injun” from Huckleberry Finn, first published in 1884. According to the Guardian, nigger is “surely the most inflammatory word in the English language,” and “appears 219 times in Twain’s book.”

Again, he rejected my explanations as “victimhood.” He even kept boasting about his own colorblindness – a true red flag! Why ask if you cannot be bothered to listen to the answer, I thought bafflingly? Even worse, rather than simply stay silent – which would have been bad enough – the other educator literally said to him “This is why I don’t get involved in such discussions with him.” They accused me of making race an issue with my students, insisting that their own learning environments were free of racism, sexism and homophobia.

They effectively closed ranks. They asserted the privilege of NOT doing any of the emotional labour of deep listening. Neither seemed capable of demonstrating understanding for the (potential) harm done when they dismiss the experiences of others, particularly given our differing corporealities. I thought of the “Get Out” scene in the eponymously named film.

“Do you have any Black teachers on your staff,” I asked knowing the answer. OK, I might have said that sarcastically. Yet, it was clear that there were no Black adults in his life with whom he could pose such questions; he was essentially calling upon me to answer his litany of ‘race’ questions.

Armed with mindfulness, I was able to get them both to express how their own corporeality impacts their classroom work. For example, one of the educators had come out to his middle-school students when confronted by their snickers when discussing a gay character in a textbook. “You have to come out,” I said, whereas I walk in the classroom Black.” Further still, they both fell silent when I pointed out that unlike either of them, my hips swing like a pendulum when I walk into the classroom. Many LGBTQ+ people are not ‘straight-acting’ i.e. appear heteronormative, as did these two. They lacked self-awareness of their own privilege and didn’t have any tools to comprehend intersectionality; this discussion clearly placed them on the defense.

I say, 100% of the emotional labour and none of the emotional reward, yet this is actually untrue. I bear the fruits of my own mindfulness readings. I see that I suffer less in those instances than previously. I rest in the comfort that though understanding didn’t come in that moment, future dialogue is still possible. As bell hooks says on the first page in the first chapter of her groundbreaking book Killing Rage: Ending Racism: “…the vast majority of black folks who are subjected daily to forms of racial harassment have accepted this as one of the social conditions of our life in white supremacist patriarchy that we cannot change. This acceptance is a form of complicity.” I accept that it was my decision to talk to these white people about race.

I reminded myself that I had foreseen the micro-aggression that he had committed the previous day when we first met. A mutual friend had hooked us up online upon his visit to this city in which we now live. I doubted that she’d mentioned my blackness. Nonetheless, I had taken the chance of being the first to greet our guest, realizing that I am in a much safer space both in terms of my own mindfulness, as well as the privilege I had asserted in coming to live here in Hanoi; I came here precisely because I face such aggression so irregularly in Vietnam that these incidents genuinely stand out.

—

Works mentioned:

Eddo-Lodge, R. (2018). Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Hanh, T. (2013). The Art of Communicating. New York: HarperOne.

hooks, b. (1995). Killing rage: Ending racism. New York: Henry Holt and Company, Inc.

A month of Black history through the eyes of a white, privileged man… an open letter

Dear friends,

Over the years, in my line of work, there was a conviction, that logic as the prevailing force allows us to see social situations around (im)passionately, impartially and fairly. Principles most important especially for anyone who dwells in social sciences. We were “raised” on the ideologies that promote inclusivity, justice and solidarity. As a kid, I remember when we marched as a family against nuclear proliferation, and later as an adult I marched and protested for civil rights on the basis of sexuality, nationality and class. I took part in anti-war marches and protested and took part in strikes when fees were introduced in higher education.

All of these were based on one very strongly, deeply ingrained, view that whilst the world may be unfair, we can change it, rebel against injustices and make it better. A romantic view/vision of the world that rests on a very basic principle “we are all human” and our humanity is the home of our unity and strength. Take the environment for example, it is becoming obvious to most of us that this is a global issue that requires all of us to get involved. The opt-out option may not be feasible if the environment becomes too hostile and decreases the habitable parts of the planet to an ever-growing population.

As constant learners, according to Solon (Γηράσκω αεί διδασκόμενος)[1] it is important to introspect views such as those presented earlier and consider how successfully they are represented. Recently I was fortunate to meet one of my former students (@wadzanain7) who came to visit and talk about their current job. It is always welcome to see former students coming back, even more so when they come in a reflective mood at the same time as Black history month. Every year, this is becoming a staple in my professional diary, as it is an opportunity to be educated in the history that was not spoken or taught at school.

This year’s discussions and the former student’s reflections made it very clear to me that my idealism, however well intended, is part of an experience that is deeply steeped in white men’s privilege. It made me question what an appropriate response to a continuous injustice is. I was aware of the quote “all that is required for evil to triumph is for good men to do nothing” growing up, part of my family’s narrative of getting involved in the resistance, but am I true to its spirit? To understand there is a problem but do nothing about it, means that ultimately you become part of the same problem you identify. Perhaps in some regards a considered person is even worse because they see the problem, read the situation and can offer words of solace, but not discernible actions. A light touch liberalism, that is nice and inclusive, but sits quietly observing history written in the way as before, follow the same social discourses, but does nothing to change the problems. Suddenly it became clear how wrong I am. A great need to offer a profound apology for my inaction and implicit collaboration to the harm caused.

I was recently challenged in a discussion about whether people who do not have direct experience are entitled to a view. Do those who experience racism voice it? Of course, the answer is no; we can read it, stand against it, but if we have not experienced it, maybe, just maybe, we need to shut up and let other voices be heard and tell their stories. Black history month is the time to walk a mile in another person’s shoes.

Sincerely yours

M

[1] A very rough translation: I learn, whilst I grow, life-long learning.

Come Together

For much of the year, the campus is busy. Full of people, movement and voice. But now, it is quiet… the term is over, the marking almost complete and students and staff are taking much needed breaks. After next week’s graduations, it will be even quieter. For those still working and/or studying, the campus is a very different place.

This time of year is traditionally a time of reflection. Weighing up what went well, what could have gone better and what was a disaster. This year is no different, although the move to a new campus understandably features heavily. Some of the reflection is personal, some professional, some academic and in many ways, it is difficult to differentiate between the three. After all, each aspect is an intrinsic part of my identity.

Over the year I have met lots of new people, both inside and outside the university. I have spent many hours in classrooms discussing all sorts of different criminological ideas, social problems and potential solutions, trying always to keep an open mind, to encourage academic discourse and avoid closing down conversation. I have spent hour upon hour reading student submissions, thinking how best to write feedback in a way that makes sense to the reader, that is critical, constructive and encouraging, but couched in such a way that the recipient is not left crushed. I listened to individuals talking about their personal and academic worries, concerns and challenges. In addition, I have spent days dealing with suspected academic misconduct and disciplinary hearings.

In all of these different activities I constantly attempt to allow space for everyone’s view to be heard, always with a focus on the individual, their dignity, human rights and social justice. After more than a decade in academia (and even more decades on earth!) it is clear to me that as humans we don’t make life easy for ourselves or others. The intense individual and societal challenges many of us face on an ongoing basis are too often brushed aside as unimportant or irrelevant. In this way, profound issues such as mental and/or physical ill health, social deprivation, racism, misogyny, disablism, homophobia, ageism and many others, are simply swept aside, as inconsequential, to the matters at hand.

Despite long standing attempts by politicians, the media and other commentators to present these serious and damaging challenges as individual failings, it is evident that structural and institutional forces are at play. When social problems are continually presented as poor management and failure on the part of individuals, blame soon follows and people turn on each other. Here’s some examples:

Q. “You can’t get a job?”

A “You must be lazy?”

Q. “You’ve got a job but can’t afford to feed your family?

A. “You must be a poor parent who wastes money”

Q. “You’ve been excluded from school?”

A. “You need to learn how to behave?”

Q. “You can’t find a job or housing since you came out of prison?”

A. “You should have thought of that before you did the crime”

Each of these questions and answers sees individuals as the problem. There is no acknowledgement that in twenty-first century Britain, there is clear evidence that even those with jobs may struggle to pay their rent and feed their families. That those who are looking for work may struggle with the forces of racism, sexism, disablism and so on. That the reasons for criminality are complex and multi-faceted, but it is much easier to parrot the line “you’ve done the crime, now do the time” than try and resolve them.

This entry has been rather rambling, but my concluding thought is, if we want to make better society for all, then we have to work together on these immense social problems. Rather than focus on blame, time to focus on collective solutions.

Thinking “outside the box”

Having recently done a session on criminal records with @paulaabowles to a group of voluntary, 3rd sector and other practitioners I started thinking of the wider implications of taking knowledge out of the traditional classroom and introducing it to an audience, that is not necessarily academic. When we prepare for class the usual concern is the levelness of the material used and the way we pitch the information. In anything we do as part of consultancy or outside of the standard educational framework we have a different challenge. That of presenting information that corresponds to expertise in a language and tone that is neither exclusive nor condescending to the participants.

In the designing stages we considered the information we had to include, and the session started by introducing criminology. Audience participation was encouraged, and group discussion became a tool to promote the flow of information. Once that process started and people became more able to exchange information then we started moving from information to knowledge exchange. This is a more profound interaction that allows the audience to engage with information that they may not be familiar with and it is designed to achieve one of the prime quests of any social science, to challenge established views.

The process itself indicates the level of skill involved in academic reasoning and the complexity associated with presenting people with new knowledge in an understandable form. It is that apparent simplicity that allows participants to scaffold their understanding, taking different elements from the same content. It is easy to say to any audience for example that “every person has an opinion on crime” however to be able to accept this statement indicates a level of proficiency on receiving views of the other and then accommodating it to your own understanding. This is the basis of the philosophy of knowledge, and it happens to all engaged in academia whatever level, albeit consciously or unconsciously.

As per usual the session overran, testament that people do have opinions on crime and how society should respond to them. The intriguing part of this session was the ability of participants to negotiate different roles and identities, whilst offering an explanation or interpretation of a situation. When this was pointed out they were surprised by the level of knowledge they possessed and its complexity. The role of the academic is not simply to advance knowledge, which is clearly expected, but also to take subjects and contextualise them. In recent weeks, colleagues from our University, were able to discuss issues relating to health, psychology, work, human rights and consumer rights to national and local media, informing the public on the issues concerned.

This is what got me thinking about our role in society more generally. We are not merely providing education for adults who wish to acquire knowledge and become part of the professional classes, but we are also engaging in a continuous dialogue with our local community, sharing knowledge beyond the classroom and expanding education beyond the campus. These are reasons which make a University, as an institution, an invaluable link to society that governments need to nurture and support. The success of the University is not in the students within but also on the reach it has to the people around.

At the end of the session we talked about a number of campaigns to help ex-offenders to get forward with work and education by “banning the box”. This was a fitting end to a session where we all thought “outside the box”.

Celebrations and Commemorations: What to remember and what to forget

Today is Good Friday (in the UK at least) a day full of meaning for those of the Christian faith. For others, more secularly minded, today is the beginning of a long weekend. For Blur (1994), these special days manifest in a brief escape from work:

Bank holiday comes six times a year

Days of enjoyment to which everyone cheers

Bank holiday comes with six-pack of beer

Then it’s back to work A-G-A-I-N

(James et al., 1994).

However, you choose to spend your long weekend (that is, if you are lucky enough to have one), Easter is a time to pause and mark the occasion (however, you might choose). This occasion appears annually on the UK calendar alongside a number other dates identified as special or meaningful; Bandi Chhorh Divas, Christmas, Diwali, Eid al-Adha, Father’s Day, Guys Fawkes’ Night, Hallowe’en, Hanukkah, Hogmanay, Holi, Mothering Sunday, Navaratri, Shrove Tuesday, Ramadan, Yule and so on. Alongside these are more personal occasions; birthdays, first days at school/college/university, work, graduations, marriages and bereavements. When marked, each of these days is surrounded by ritual, some more elaborate than others. Although many of these special days have a religious connection, it is not uncommon (in the UK at least) to mark them with non-religious ritual. For example; putting a decorated tree in your house, eating chocolate eggs or going trick or treating. Nevertheless, many of these special dates have been marked for centuries and whatever meanings you apply individually, there is an acknowledgement that each of these has a place in many people’s lives.

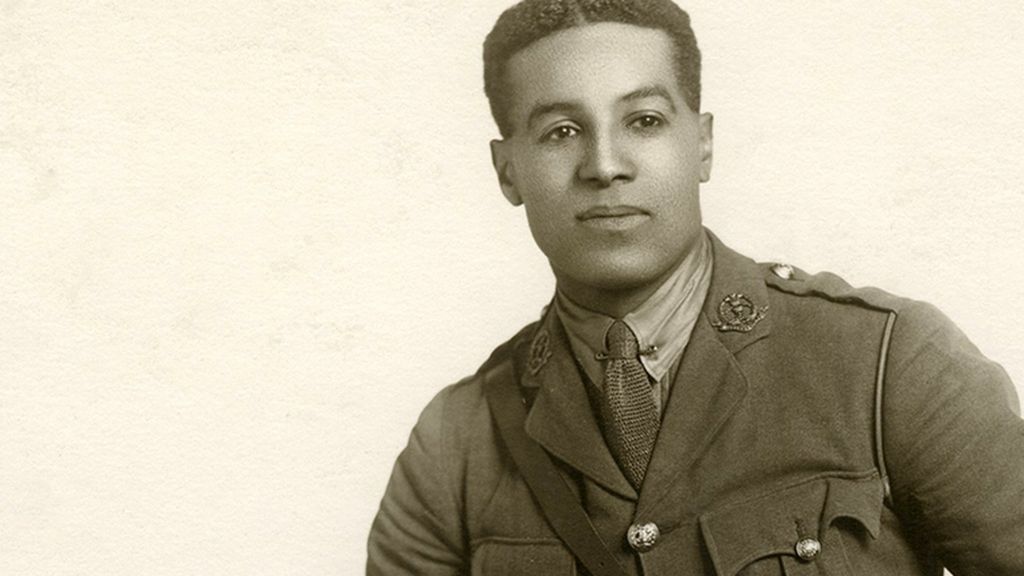

Alongside these permanent fixtures in the year, other commemorations occur, and it is here where I want to focus my attention. Who decides what will be commemorated and who decides how it will be commemorated? For example; Armistice Day which in 2018 marked 100 years since the end of World War I. This commemoration is modern, in comparison with the celebrations I discuss above, yet it has a set of rituals which are fiercely protected (Tweedy, 2015). Prior to 11.11.18 I raised the issue of the appropriateness of displaying RBL poppies on a multi-cultural campus in the twenty-first century, but to no avail. This commemoration is marked on behalf of individuals who are no longing living. More importantly, there is no living person alive who survived the carnage of WWI, to engage with the rituals. Whilst the sheer horror of WWI, not to mention WWII, which began a mere 21 years later, makes commemoration important to many, given the long-standing impact both had (and continue to have). Likewise, last year the centenary of (some) women and men gaining suffrage in the UK was deemed worthy of commemoration. This, as with WWI and WWII, was life-changing and had profound impact on society, yet is not an annual commemoration. Nevertheless, these commemoration offer the prospect of learning from history and making sure that as a society, we do much better.

Other examples less clear-cut include the sinking of RMS Titanic on 15 April 1912 (1,503 dead). An annual commemoration was held at Belfast’s City Hall and paying guests to the Titanic Museum could watch A Night to Remember. This year’s anniversary was further marked by the announcement that plans are afoot to exhume the dead, to try and identify the unknown victims. Far less interest is paid in her sister ship; RMS Lusitania (sank 1915, 1,198 dead). It is difficult to understand the hold this event (horrific as it was) still has and why attention is still raised on an annual basis. Of course, for the families affected by both disasters, commemoration may have meaning, but that does not explain why only one ship’s sinking is worthy of comment. Certainly it is unclear what lessons are to be learnt from this disaster.

Earlier this week, @anfieldbhoy discussed the importance of commemorating the 30th anniversary of the Hillsborough Disaster. This year also marks 30 years since the publication of MacPherson (1999) and Monday marks the 26th anniversary of Stephen Lawrence’s murder. In less than two months it will two years since the horror of Grenfell Tower. All of these events and many others (the murder of James Bulger, the shootings of Jean Charles de Menezes and Mark Duggan, the Dunblane and Hungerford massacres, to name but a few) are familiar and deemed important criminologically. But what sets these cases apart? What is it we want to remember? In the cases of Hillsborough, Lawrence and Grenfell, I would argue this is unfinished business and these horrible events remind us that, until there is justice, there can be no end.

However, what about Arthur Clatworthy? This is a name unknown to many and forgotten by most. Mr Clatworthy was a 20-year-old borstal boy, who died in Wormwood Scrubs in 1945. Prior to his death he had told his mother that he had been assaulted by prison officers. In the Houses of Parliament, the MP for Shoreditch, Mr Thurtle told a tale, familiar to twenty-first century criminologists, of institutional violence. If commemoration was about just learning from the past, we would all be familiar with the death of Mr Clatworthy. His case would be held up as a shining example of how we do things differently today, how such horrific events could never happen again. Unfortunately, that is not the case and Mr Clatworthy’s death remains unremarked and unremarkable. So again, I ask the question: who decides what it is worthy of commemoration?

Selected Bibliography:

James, Alexander, Rowntree, David, Albarn, Damon and Coxon, Graham, (1994), Bank Holiday, [CD], Recorded by Blur in Parklife, Food SBK, [RAK Studios]

Have you been radicalised? I have

On Tuesday 12 December 2018, I was asked in court if I had been radicalised. From the witness box I proudly answered in the affirmative. This was not the first time I had made such a public admission, but admittedly the first time in a courtroom. Sounds dramatic, but the setting was the Sessions House in Northampton and the context was a Crime and Punishment lecture. Nevertheless, such is the media and political furore around the terms radicalisation and radicalism, that to make such a statement, seems an inherently radical gesture.

So why when radicalism has such a bad press, would anyone admit to being radicalised? The answer lies in your interpretation, whether positive or negative, of what radicalisation means. The Oxford Dictionary (2018) defines radicalisation as ‘[t]he action or process of causing someone to adopt radical positions on political or social issues’. For me, such a definition is inherently positive, how else can we begin to tackle longstanding social issues, than with new and radical ways of thinking? What better place to enable radicalisation than the University? An environment where ideas can be discussed freely and openly, where there is no requirement to have “an elephant in the room”, where everything and anything can be brought to the table.

My understanding of radicalisation encompasses individuals as diverse as Edith Abbott, Margaret Atwood, Howard S. Becker, Fenner Brockway, Nils Christie, Angela Davis, Simone de Beauvoir, Paul Gilroy, Mona Hatoum, Stephen Hobhouse, Martin Luther King Jr, John Lennon, Primo Levi, Hermann Mannheim, George Orwell, Sylvia Pankhurst, Rosa Parks, Pablo Picasso, Bertrand Russell, Rebecca Solnit, Thomas Szasz, Oscar Wilde, Virginia Woolf, Benjamin Zephaniah, to name but a few. These individuals have touched my imagination because they have all challenged the status quo either through their writing, their art or their activism, thus paving the way for new ways of thinking, new ways of doing. But as I’ve argued before, in relation to civil rights leaders, these individuals are important, not because of who they are but the ideas they promulgated, the actions they took to bring to the world’s attention, injustice and inequality. Each in their own unique way has drawn attention to situations, places and people, which the vast majority have taken for granted as “normal”. But sharing their thoughts, we are all offered an opportunity to take advantage of their radical message and take it forward into our own everyday lived experience.

Without radical thought there can be no change. We just carry on, business as usual, wringing our hands whilst staring desperate social problems in the face. That’s not to suggest that all radical thoughts and actions are inherently good, instead the same rigorous critique needs to be deployed, as with every other idea. However rather than viewing radicalisation as fundamentally threatening and dangerous, each of us needs to take the time to read, listen and think about new ideas. Furthermore, we need to talk about these radical ideas with others, opening them up to scrutiny and enabling even more ideas to develop. If we want the world to change and become a fairer, more equal environment for all, we have to do things differently. If we cannot face thinking differently, we will always struggle to change the world.

For me, the philosopher Bertrand Russell sums it up best

Thought is subversive and revolutionary, destructive and terrible; thought is merciless to privilege, established institutions, and comfortable habits; thought is anarchic and lawless, indifferent to authority, careless of the well-tried wisdom of the ages. Thought looks into the pit of hell and is not afraid. It sees man, a feeble speck, surrounded by unfathomable depths of silence; yet it bears itself proudly, as unmoved as if it were lord of the universe. Thought is great and swift and free, the light of the world, and the chief glory of man (Russell, 1916, 2010: 106).

Reference List:

Russell, Bertrand, (1916a/2010), Why Men Fight, (Abingdon: Routledge)