Home » Criminology (Page 19)

Category Archives: Criminology

Stop strip searching children!

The Metropolitan Police are under constant criticism, more than any other police force, for at least as long as I have been a criminologist. Their latest scandal began with the case of Child Q, a 15 year old girl who was strip searched in school while she was menstruating after being suspected of carrying cannabis. No drugs were found and Child Q was extremely traumatised, resulting in self-harm and a suicide attempt. Tré Ventour recently wrote a blog about Child Q, race and policing in education here but following this week’s Children’s Commissioner report, there’s so much more to discuss.

The report focussed on the Metropolitan Police who strip searched 650 children in 2 years, many (23%) of whom were searched without the presence of an appropriate adult and as we criminologists would expect, the children were disproportionately Black boys. These findings were not surprising or shocking to me, and I also know that the Metropolitan Police force are not just one bad apple in this respect. The brutal search of Child Q occurred in 2020 but incidences such as these have been happening for years.

A teenage boy aged 17 was subject to an intimate search in 2019 where the police breached a number of clauses of PACE, ultimately resulting in the boy receiving an apology and £10,000 damages for the distress caused by the unlawful actions. These actions started with basic information being withheld such as the police officer failing to identify himself and informing the boy of his rights and ended with the strip search being undertaken without an appropriate adult present, in the presence of multiple officers, without authorisation from a senior officer and with no justification for the search recorded in the officer’s pocket book. Now I understand that things may be forgotten in the moment when a police officer is dealing with a suspect but the accumulation of breaches indicates a more serious problem and a disregard to the rights of suspects in general but children more specifically.

These two cases are the cases of children who were suspected of carrying cannabis, an offence likely to be dealt with via a warning or on the spot fine. Hardly the crime of the century warranting the traumatising strip searching of children. And besides, we criminologists know that the war on drugs is a failed project. Is it about time we submit and decriminalise cannabis, save police time and suspect trauma?

What happens next is a slightly different story. Strip searching in custody is different because as well as searching for contraband, it can also be justified as a protective measure where there is a risk of self-harm or suicide. Strip searching of children by the police has risen in a climate of fear surrounding deaths in custody, and it has been reported that there could be an overuse of the practice as a result of this. When I read the report, I recalled the many conversations I have had over the years with my friend Rosie Flatman who is a practitioner who specialises in working with victims of Child Sexual Exploitation (CSE) and other forms of abuse. Rosie has worked with many girls who have been subject to strip searches when in custody. She told me how girls would often perceive the search as punishment for being what the police believed was disruptive. That is not to say that the police were using strip searches as punishment, but that is how girls would experience it.

Girls in custody are often particularly vulnerable. Like Rosie’s clients, many are victims and have a number of compounding vulnerabilities such as mental ill health or they may be looked after children. Perhaps then, we need to look at alternatives to strip searching but also custody for children, particularly for those who have suffered trauma. Rosie, who has delivered training to various agencies, suggests only undertaking strip searches where absolutely necessary and even then, using a trauma informed approach. She argues that even the way the procedure and justification is explained can make a big difference to the amount of harm caused to vulnerable children in police custody.

There’s no I in teamwork but maybe there’s space for me and you?

Teamwork is often promoted as a valuable transferable skill both by universities and employers. However, for many the sheer mention of this type of group activity is enough to fill them with dread. This is a shame, and I want to use this blog to explain why.

I’m definitely not one for sports, but even I cannot avoid the discourse around women’s football and Euro 2022. Much has been written about the talents and skill of England’s Lionesses, of which I know very little. Equally there has been disquiet around the overwhelming whiteness of the team, an inequality I am very familiar with throughout my studies of crime, criminality and criminal justice. Nevertheless this blog isn’t about inclusion and exclusion, but about teamwork. Football, like many activities is not a solo enterprise but a group activity. All members need to be able to rely upon their team mates for support, encouragement and ultimately success. If a player doesn’t turn up for training, doesn’t engage in sharing space, passing the ball and so on, the team will fail in their endeavours. Essentially, the team must be on the same page and be willing to sacrifice individuality (at times) for the good of the team. But football isn’t the only activity where teamwork is crucial.

One only has to imagine the police, another overwhelmingly white institution, but with a very different mandate and different measures of success. Here a lack of support from team mates could be a matter of life and death. Even if not so severe, the inability to work closely with other officers in a team can make professional and person life extraordinarily difficult to maintain. It has repercussions for individual offices, the police force itself and indeed, society.

Whilst I’ve the made the case for teamwork, it is not clear what makes a good team, or how it could be maintained. Do all teams work? Personal experience tells me that when members have very different agendas and lose sight of the main objective, team work can be very challenging, if not impossible. There has to be a buy in from all members, not just some. There has to be space for individuals to develop themselves as well as the wider team. However, when the individual aims continue to take priority over the collective, cracks emerge. The same experiences suggest that teamwork cannot be accomplished instantly regardless of intent. Teams take a long time to build rapport, to bond, to gain trust across members and this cannot be hurried. Furthermore, this process requires continuing individual and collective reflection and development. So where can we find an example of such excellence (outside of the wonderful Criminology Team, of course)?

I recently watched the BBC 4-part documentary My Life as a Rolling Stone. Produced to mark 60 years of the band, the documentary explores the lives of Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, Ronnie Wood and the late, Charlie Watts. There were lots of interesting aspects to each part, but the most striking to me was the sense of belonging. That the Rolling Stones are a cohesive team, with each member playing very different parts, but all essential to not only the success of the band, but also to the well-being of the four men. Alongside discussions around creativity, musicality and individual skills, they describe drug taking, alcohol abuse, romantic relationships, fights, falling out and making up. There were periods of silence, of discord and distrust and periods of celebration and sheer personal and collective joy. Working together they provide each other with exactly what they need to thrive individually and collectively.

These men have made more money than most of us can dream of. They have been to parts of the world and seen things that most of us will never see. All of them are heading toward 80 but keep writing and performing. More importantly for this blog, they seem to illustrate what teamwork looks like, one where communication is key, where disputes must be resolved one way or another, regardless of who was right and who was wrong and where the sheer sense of needing one another, belonging remains paramount. I could use a dictionary definition of teamwork, but it seems to me the Rolling Stones say it better than I ever could:

“You can’t always get what you want

But if you try sometime

You’ll find

You get what you need”

(Jagger and Richards, 1969).

A Punky Reggae Party

In June 1977, 45 years ago, I saw the Queen, albeit fleetingly, being driven past Piccadilly Circus en-route to Buckingham Palace for the culmination of the Silver Jubilee celebrations. I wasn’t there for the party. I was making my way to Camden Town and the rehearsal studios used by the Punk-inspired band Subway Sect, who my friend from school had joined as their drummer. The studio, part of a crumbling yard of railway buildings, some still bombed out from the War, would soon begin its transformation into trendy Camden Market.

Punk shared an interesting crossover with Black music culture, in particular reggae. As teenagers, most of us growing up in the 70s were familiar with Blues and Tamala Motown, but reggae was new to me, especially the Heavy Dub style popular in the Jamaican community. The man largely responsible for my education was Don Letts, the House DJ at The Roxy in Neil St, Covent Garden. Originally a fruit and veg warehouse, between 1976 and 1978 the Club shot to fame/notoriety as the top Punk venue in London. The problem for the promoters was that in 1977 the scene was so embryonic there were as yet no home-grown punk records to play. So, in the gaps between live bands, Don played what he wanted, namely reggae, which went down well with the mostly white crowd. To quote from his website: “he came to notoriety in the late 70s as the DJ that single handedly turned a whole generation of punks onto reggae”. In fact, the combination became so popular that Bob Marley’s Punky-Reggae Party released in 1977 as a 12 inch (Jamaica only) and as the B-side to Jamming, reached number 9 in the UK singles charts. Don’s choice of tracks from his Roxy days are captured in the critically acclaimed compilation Dread Meets The Punk Rockers Uptown (Heavenly Records).

Scroll forward a couple of years and I’m working as assistant van driver to my boss Morris, a Jamaican-born reggae fan. He was involved in the local music scene and sometimes I would help him set up a Sound System for private house parties, in and around Brixton. We would use the work van, a sackable offence given the prestige brand name of our West End employer, but worth the risk. Think Small Axe: Lovers Rock, but with more sound gear and ganja-smoking Rastas, and you’ve got the picture. While sometimes out of my comfort zone, it was uplifting to witness first-hand a community at one with its own identity while lobbying for change in wider society that remained indifferent at best.

It was also a time in London when the Metropolitan Police stop and search “SUS” law reigned high. I witnessed several occasions where Morris was subject to blatant racial harassment. Once I was on a delivery to an exclusive residential part of Town. On these visits we played a game, coined by Morris, as Dropsy or Tipsy – would we be offered a Dropsy (cup of tea/coffee) or a cash tip for the delivery, typically a sofa or expensive Persian rug? The winner was the one who made the right call in advance. We parked in the street and as we got out several police officers on foot suddenly approached Morris and demanded to know what he was doing, despite the rather obvious fact he was at work. When they saw me, the situation cooled off, but the aggressive tone of the questioning was clear and present intimidation of a black man, whose only ‘offence’, while going about his legitimate business, was to be in a white, rich area. I wish I could say this was a one-off. Unfortunately, we all know that’s not the case. Another time relates to the shocking mistreatment he got crossing a picket line. The work van was kept in a British Road Services Depot at Elephant and Castle. We both turned up on the day a lightning strike had been called by the Transport and General Workers Union. I understand emotions can run high in these situations, but there was no excuse for the barrage of racial abuse he took from sections of the crowd. He brushed it off with characteristic good humour, but the episode tainted my view of trade unions ever since.

As this is a criminology blog I should probably throw in an example of real-life criminality. It happened mid-morning one Friday following a drop-off in busy Bishopsgate. Returning to the van I noticed a castor wheel on the pavement. “Looks like it’s come from one of our sofas” I remarked. It had. When we pulled back the shutter, the van was empty. Everything we’d loaded up an hour ago was gone. Sofas, walnut dressers, rugs, porcelain table lamps, all cleaned out. The castor was all that was left! Robbed in broad daylight, next to a bus stop. In panicked disbelief we asked those in the queue if they’d seen anything but we were wasting our breath. It was left to Mr Farooqui, the long-suffering Despatch floor manager, to take the heat from angry customers as he rang round to tell them the good news. Needless to say, management weren’t impressed and dished out first and final written warnings. Soon after we went our separate ways.

Meanwhile, the overlap between black and white youth culture in London was being fostered in creative ways. Rock Against Racism (RAR), founded in 1976 along with the Anti-Nazi League (ANL), a year later, were both set up to combat a surge in far-right extremism. Music, especially the cross-over between various genres including punk and reggae, was an important enabler in that it found common ground from which more overtly political discussions could take place. I was one of the many thousands who, in April 1978, joined The Clash, Steele Pulse and others at Victoria Park, Hackney, in what was RAR’s finest hour. Also in the audience that day was Gerry Gable, the veteran anti-fascist campaigner and founder of Searchlight magazine, whose archive is hosted here at the University. I spoke to Gerry about this and he has very fond memories of the day and his role in helping it come about through his associations with both RAR and the ANL.

So, in the year of the Platinum Jubilee, has popular music culture continued as a positive force for race integration since the punky-reggae days of 77? It’s probably a PhD project or two (dozen), but Bob Marley sums it up for me nicely:

What did you say?

Rejected by society

Treated with impunity

Protected by my dignity

I search for reality

If by the search for reality we mean certainty, then how certain are we things have changed for the better? My experience is that, on average, they have, and that music has played its precious role in bring people closer together. The key here is “on average”. If by reality we mean a search for legitimacy, there is evidence to the contrary. Differences of course remain, and there is no room for complacency. The one pledge we must agree on though is to never stop searching – for melody, for rhythm, for harmony.

Chaos in Colombo: things fall apart

Following the mutiny that we witnessed in Downing street after members of the Johnson’s cabinet successfully forced him to resign over accusations of incompetency and the culture of inappropriate conducts in his cabinet, the people of Sri Lanka have also succeeded in chasing out their President, G. Rajapaksa, out of office over his contributions to the collapse of the country’s economy. This blog is a brief commentary on some of the latest events in Sri Lanka.

Since assuming office in 2019, the government of Rajapaksa has always been indicted of excessive borrowing, mismanagement of the country’s economy, and applying for international loans that are often difficult to pay back. With the country’s debt currently standing at $51bn, some of these loans, is claimed to have been spent on unnecessary infrastructural developments as well as other ‘Chinese-backed projects’, (see also; the Financial Times, 2022). Jayamaha (2022; 236) indicated that ‘Sri Lanka had $7.6 billion in foreign currency reserves at the end of 2019. However, by March 2020, it had exhausted its reserves to just $1.93 billion.’ One of Rajapaksa’s campaign promises was to cut taxes, which he did upon assuming office. His critics faulted this move, claiming it was unnecessary at that particular time. His ban on fertilizers, in a bid for the country to go organic (even though later reversed), had its own effect on local farmers. Rice production for example, fell by 20% following the ban – a move that eventually forced the government to opt for rice importation which was in itself expensive (see also; Nordhaus & Shah 2022). Critics warned that his investments and projects have no substantial and direct impact on the lives of the common people, and that what is the essence of building roads when the common people cannot afford to buy a car to ride on those roads? The fact that people have to queue for petrol for 5 days and only having to work for 1 day or where families cannot afford to feed their children simply shows how the government of Rajapaksa seem to have mismanaged the economy of the country. Of course, the problem of insecurity and the pandemic cannot be left out as crucial factors that have also impacted tourism levels and the economy of the country.

Foreign reserves have depleted, the importation of food is becoming difficult to actualise, living expenses have risen to high levels, the country is struggling with its international loan repayments, the value of Rupees has depreciated, there is inflation in the land, including shortages of food supplies and scarcity of fuel. Those who are familiar with the Sri Lanka’s system will not be particularly surprised at the nationwide protests that have been taking place in different parts of the country since May, because the Rajapaksa’s regime was only sitting on a keg of gun powder, ready to explode.

In an unprecedented fashion on July 9, several footages and images began to emerge online showing how protesters had successfully overpowered the police and had broken into the residence of the President. Their goal was to occupy the presidential palace and chase the president out of his residence. In fact, there are video footages online allegedly showing the motorcade of the president fleeing from his residence as the wave of protest rocked the capital.

Upon gaining entry into the innermost chambers of the president’s dwelling, protesters started touring and taking selfies in euphoria, some of them had quickly jumped into the presidential shower, others helped themselves to some relaxation on the president’s bed after days of protests, some were engaged in a mock presidential meeting in the president’s cabinet office, some preferred to swim in the president’s private pool while others helped themselves to some booze.

Indeed, these extraordinary scenes should not be taken for granted for they again reaffirm WB Yeats classic idea of anarchy (in ‘the second coming’ poem), being the only option to be exercised when the centre can no longer hold.

Of course, some may ask that now that they have invaded the presidential villa, what next? In my view, the people of Sri Lanka seem to be on the right direction as President Rajapaska has eventually bowed to pressure and agreed to resign. The next phase now is for the country to carefully elect a new leader who will revive the sinking ship, amend the economic policies, foster an effective democratic political culture which (hopefully) should bring about a sustainable economic plan and growth reforms.

Importantly, this is a big lesson not just for the political class of Sri Lanka, but for other wasteful leaders who continue to destroy their economies with reckless and disastrous policies. It is a lesson of the falcon and the falconer – for when the falcon can no longer hear the falconer, scenes like these may continue to be reproduced in other locations of the world.

Indeed, things fell apart in Colombo, but it is hoped that the centre will hold again as the country prepare to elect its new leaders.

Here is wishing the people of Colombo, and the entire Sri Lankans all the best in their struggle.

References

Financial Times (2022) [Twitter] 20 July. Available at: https://mobile.twitter.com/FinancialTimes/status/1549554792766361603

Jayamaha, J. (2022) “The demise of Democracy in Sri Lanka: A study of the political and economic crisis in Sri Lanka (Based on the incident of the Rambukkana shooting)”, Sprin Journal of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences, 1(05), pp. 236–240. doi: 10.55559/sjahss.v1i05.22.

Nordhaus, T & Shah S, (2022) In Sri Lanka, Organic Farming Went Catastrophically Wrong, March 5, FP. Available at: https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/03/05/sri-lanka-organic-farming-crisis/

Coup D’Twat: Boris is Just a Smokescreen

NB: I am not funny enough to have singlehandedly come up with the term “coup d’twat” to describe the current constiutional horror show. That honour belongs to Twitter, which I first saw referenced by the radical psychologist Guilaine Kinouani. At the moment, my Twitter and Facebook timeline is congested with memes and vines relating to the crisis at hand … and much of that I find is due to the notion if we do not laugh now, we will cry. In times of crisis, clearly we do not look to the politicians, the hedgefund managers or the corporates. We do look to the artists, and people that do make memes are artists (because not everybody can do it and do it well!). If it was easy, we would all do it!

In criminology, it is impossible to look at situations like this and not be thinking of the bigger picture. It is very easy to stay focused on Boris Johnson who has made a career appearing as a non-threatening bumbling buffoon. At the same time he is accountable not to the people that voted for him, but the big donor money that sits behind the Conservative Party. If the prime minister has been pushed out (though we won’t know if he actually leaves until September … he may just do a Trump), it’s not because of his party but because oligarchs have seen that he is no longer useful and bad for business.

This comes attached to the erosion of public freedoms and a public historical amnesia of how hard our ancestors had to fight for the things we take for granted today.

Only two centuries ago my ancestors were enslaved on the islands of Grenada and Jamaica, and before abolitionists were fighting pro-enslavement MPs in Britain, the enslaved were leading rebellions across the Caribbean and at the point of kidnap in Africa. It is by some miracle I am with you now to tell these stories of disssent when so many Black people were killed from disease and hunger in the holes and hulls of European slave ships. With the prime minister “leaving” in September, I am more conscious of the wider system and how fascism arrives in tandem with people telling you to stop over-reacting.

The constitutional crisis we are in now is a coup d’twat built inside a wider prism of complacency. It claims there is “a time and place” to protest and challenge, and that is never all the time (when it should be). In the fights our ancestors had for freedom, we forget how hard it is to maintain that. It appears democracy in Britain begins and ends at voting every four years, and you must accept your lots in life in that four-year window. Within my sentient life now coming to my twenty-seventh year, my generation in the UK probably do not have living reference points for democracy beyond that narrow definition.

Most people believe they have no say in the forces that dictate their lives. On university campuses, it is increasingly clear that the voices of corporate senior leadership teams / governors are favoured more than lecturers and students. The Government has been criticised for its entanglements with oligarchy, but what about universities that focus more on individualism over community? The events since 6th July are being reproduced in various ways in education where neoliberal capitalism runs brigand. Out of touch senior leadership make choices on things they have no knowledge of and do not care about concerns of students if it doesn’t make them money. The concerns of lecturers get shafted too.

Meanwhile, senior leadership continue to leverage students as cash-cows while not taking decolonial approaches to education seriously. People that challenge the University in these ways get made into problems, and sometimes destroyed. For democracy to work, challenge must always be invited. This doesn’t stop with parliament but extends to all breathing institutions. At universities, when you disempower students they then feel they do not have the right to challenge information in class. This does not look like a democratic institution.

When academics challenge senior leadership teams only to be met with sour faces and gaslighting, you see there is no democracy no matter how much they strike – as the institution meets “troublemakers” (the complainers) with silence.

Boris Johnson will not see himself as a disgrace as he will always be part of that “canteen culture“, and you cannot judge someone to the standards that do not even see themselves in. Those same behaviours of not being accountable are in every institution. The only difference is as prime minister, is power. He is part of the gilded circle, leaving number ten in disgrace or not. These politicians have survived much much worse and will again. On both sides of the bench, there are too many millionaires who know nothing of what it means to be hungry and to do without.

Boris leaving is a smokescreen. Labour or Conservative the wider system is crooked and has been for years, all while there is a crisis of confidence in democracy in parliament and outside of it.

Forensic science and police procedure – how the investigative process really works

This is an interesting blog on the “CSI effect” from our favourite Crime writer Vaseem; he is making some fair points worth considering before watching another crime show!

(Article originally written for the Guppy Chapter of Sisters in Crime.)

The CSI effect. We’ve all heard the term, but perhaps only those who work in and around law enforcement and the judicial system wince with pain each time it enters their field of view. The term was coined to describe the way the TV show CSI: Crime Scene Investigation (and its various derivatives) has warped the popular perception of how forensics, crime scene investigation, and the investigative process in general, works. This warping effect has embedded itself to such an extent that some judges feel obliged to warn juries in advance that they must disregard whatever they might have gleaned from such shows when they sit at trial.

So what is myth and what is real when it comes to modern crime investigation?

First, an introduction: why am I qualified to talk…

View original post 2,341 more words

Roe v. Wade: Trumpism on Biden’s watch

What can I, a cisgender man, say about abortion? I don’t really have an answer to that. But I do think it is vital that cis men do pick up some of the emotional labour. Recently, I have been talking to myself about Roe and hopefully this blog at the very least provokes questions. Increasingly, I have been made aware of the silence of cisgender men on Roe v. Wade while people from marginalised genders continue to pick up the emotional labour. Here, I aim to create what the late US senator John Lewis referred to as “good trouble … necessary trouble” to poke holes in the status quo.

Also, what could Roe v. Wade mean for us in Britain? The overturning of Roe situates the continued upholding of white supremacy through racial and gendered violence. First of all, in America there sits a racist enterprise that did not start with Trump (as convenient that would be to claim) but is centuries in the making. In his 1987 book The Birth Dearth, presidential advisor and author Ben Wattenberg wrote:

“The major problem confronting the United States today is there aren’t enough white babies being born. If we don’t do something about this and do it now, white people will be in the numerical minority and we will no longer be a white man’s land.”

At the time he wrote this, he was criticised as a white supremacist, as in the 1980s, the majority of immigrants moving into the United States were Black and Brown. In the book, he also claims 60% of the fetuses being aborted where white and if they could be kept alive, it would solve what he called “the birth dearth.” And what he was talking about is exactly as it sounds … eugenics.

In their 2021 essay ‘The Birth Dearth: The Sad but True Reason Why What’s Happening in Texas Right Now Shouldn’t Surprise You’, Ajah Hales writes

“Wattenberg peddled soft eugenics dressed up as concern for the economy and democracy across the globe. Becoming the world’s most powerful nation was, to Wattenberg, due to the efforts, values and contributions of white men, particularly Western Europeans.

Now the battle for control of white women’s uteri moved from a moralistic argument to a nationalistic one. I say white women because the reproductive organs of Black and other women of color were being policed in a totally different way.

While white women were encouraged to have babies, women of color were being forcibly sterilized and having dangerous forms of birth control pushed on them, sometimes through the use of financial incentives or time off of prison sentences.”

Over the past few days since the overturning of the Roe precedent, I have seen numbers of people (especially cisgender white women) posting memes and images of that ilk from Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale to depict a “new” dystopian present. It comes in the thinking of a “new” needed “feminist” reply to the overturning of Roe, as if the policing of people’s bodies only started now. Where was that support when Black women were asking in 2020 in response to the Murder of Breonna Taylor, and prior with the further murders of Black women by police? #SayHerName. Long story short, state violence that has always discriminated against the Global Majority, many white women are now seeing that what has frequently occurred in the long reach of colonial history, can also happen to them!

The use of The Handmaid’s Tale is offensive because the novel is basically, a study in whitewashing what happened to Black and Brown women historically in the United States, only then adapting it to white women’s lives in a fictional context. Only by applying it to white women, did a number of white people understand Black and Brown trauma, even more concerning that in a 2020 exit poll 55% of white women voters reportedly voted Trump. Furthermore, in America today it is also a crime for most ex-convicts to vote where this overturning of Roe will further disenfranchise many. Not just cis women but also transgender men, as well as many nonbinary and and intersex people. So, in many states now, access to safe abortions have now been criminalised. As Katie Halper said in a Double Down News broadcast,

“We’re still living in Trump’s America. Nothing has fundamentally changed, it’s just gotten worse. The policies Trump wanted to carry out are now being carried under Joe Biden’s watch.”

katie halper (2022)

The prevalence around guns and the policing of bodies (particlarly marginalised genders) takes me back to the ethos America was founded on – violence, violence, and more violence – where guns have more rights than sentient life. White terrorism continues in the 21st century just as it did 17th, 18th, 19th and 20th centuries. In 2022 at a Save America Rally, GOP congresswoman Mary Miller told an audience the overturning of Roe was “a historic victory for white life” bringing us back to The Great Replacement theory and a white fear of being outnumbered by Black and Brown people (that same fear could be argued to have been present in Enoch Powel’s 1968 River of Blood speech, further to changes to 1970s UK policing, as well as the implementation of the Nationality and Borders Act which could impact up to 6m people).

There is also a further Christian supremacy in the politicising of abortion to gain votes, and Christianity was historically the trojan horse for white supremacy. Intertwined with male supremacy (patriarchy … emphasis on white men here, but clearly not exclusively … i.e Black / Brown Conservatives and “nice white women“) this revisits what I like to call the Mad Men Thesis after the 2007 drama series set in the 1960s – discussing a patriarchy that asserted a woman’s place was to “serve” men, be it at work (doing the labour while men took credit) or home making house and raising children (while the husband took credit). These sorts of men also pushed values that protected their status (see phalluscentrism and what Laura Mulvey writes on the Male Gaze … misogyny in film), further to obsessions with holding power of over women.

This is in essence the boomerang movement of patriarchal white supremacy, as what frequently occurred in the domicile and / or global in/external elsewhere to Black and Brown people can happen to white people too if the state chooses! What’s been frequently said is that this sort of violence starts with us, but what gets missed is that it doesn’t end with us. For example, the Sarah Everard vigil was a stark reminder that police brutality that has long haunted Black and Brown people’s lives, can also impact the lives of cis white women even within their bubble of whiteness. Everyone who lives under the state is at risk of state violence depending on proximity (we have more in common than not).

However, in a UK context, it is interesting but not surprising to see many Britons othering the overturning of Roe v. Wade as an exclusively American issue when as we know all too well, where America leads Britain all too often follows. Whilst we most definitely should be in solidarity with our friends and colleagues in the United States, we must not get complacent in that textbook British exceptionalism. The overturning of Roe is fascism and fascism is also happening on British soil too. Since as of now, both the Nationality and Borders Bill (known as the Borders Act) and the Crime, Policing and Sentencing Bill (Courts Act) are etched into law. It doesn’t take much thought to see how a Roe v Wade situation could easily happen here.

In October 2019, Northern Ireland decriminalised abortion, but access to abortion is still precarious and abortion services have not yet been commissioned. And as Rachel Connolly writes “… the health minister Robin Swann, has refused to comply.” Amid the British state’s actions in criminalising asylum seekers and fostering a culture that seeks to normalise anti-trans violence (#RowlingGate) as the Tories continue to attack the rights of trans people as well, I hear a lot of this could never happen in Britain rhetoric. But it could happen in Britain and it is happening in Britain: anti-abortion laws are not only a gender issue but a human rights issue, where anti-abortion discourse harms on numerous grounds.

For example trans men and intersex people will also be impacted, further to working-class, the disabled and Black and Brown people. If what happened in America comes to Britain, the Tory horror show will grow darker while the National Health Service is auctioned off to the highest bidder … many of them American corporations where profits will be put ahead of people’s lives and wellbeing, as the NHS is victim of a forty-year stealth attack that started under Margaret Thatcher. With the NHS being sold off, how will those who rely on it be able to afford abortions, let alone access one, should they become criminalised too? And further plans to make “reforms” to the Human Rights Act, leave us in a vulnerable state of affairs. Britain is not America, but that “special relationship” appears in more ways than one.

Like the Borders Act as well as the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act, Roe v Wade didn’t just happen at random – and it also implicates far-right fantasies lead by Black and Brown conservatives as Nel Abbey tweeted: “The unspeakably dark side of having to work twice as hard and be twice as good to stand out” where Black judge Clarence Thomas revisits how white supremacy can come with a Black face.

During his confirmation hearing, he accused people of a “high-tech lynching” when he was accused of sexually harrassing Anita Hill. And as Katie Halper states, “one could argue without Joe Biden, Clarence Thomas would not be on the Supreme Courts today.” Yet, the Dems had ample chances to codify Roe into law but didn’t because … no backbone. As Obama stated in 2009, that an abortion rights law wasn’t a top priority. And really to sit at the table, you need (to varying degrees) emulate the master. As whiteness is as much exclusively about “being white” as patriarchy is as much exclusively about “being a man.”

America was a British colony for years and the US was founded on social discourses of industrialised rape via enslavement to create labour; kidnap of Indigenous children via white supremacist boarding schools; the enslavement of African children co-opted into the plantation economy, and restrictive immigration policies (such as the Chinese Exclusion Act 1882). Also, consider recently with anti-trans legislation being pushed through on multiple fronts, as well as sodomy laws that still existed in sixteen states as of 2020.

With the rolling back of human rights in Britain including on immigration and protest, we may then see future far-right attacks against reproductive freedoms that will hurt the marginalised worst of all. Just like in America, here in Britain we can’t vote our way out of this and we must make it “politically painful” (as Katie Halper says) for politicians to continue their middle-of-the-road politics. Call them Labour or Conservative, they will not save us and will leave us to rot in the gutter. More recently, unionists like Mike Lynch have proved a better opposition to the Tories than Kier Starmer (let alone Labour) symbolic of the power of working-class resistance in bringing political pain to a media class in cahoots with Government.

In the long reach of American history following and predating Reagan, social murder is commonpractice in the daily drumbeat we call structural violence. We lay naked in the synapse of crime and punishment, and the overturning of Roe is the latest iteration where what has been long-known by many Black and Brown people, many white people are now taking notice as it now impacts them where they sleep.

Under the rhetoric of anti-abortion, these people are pro-life until the child is born. But these same people will then support easy access to lethal weapons, where an AR-15 whose sole purpose is to kill has more rights than life itself. British exceptionalism has no place in this discussion because if a Roe comes to Britain and passes like in America, many of us are going to die. And you will never see the murderer.

Capitalism and tourism: an ethical conundrum

After a two-year delay in our holiday booking due to the Covid pandemic, my wife and I were fortunate enough to spend a two-week holiday in Cape Verde (Cabo Verde) on the island of Sal. We’ve been lucky enough to visit the islands several times over the last ten years. Our first visit was to Boa Vista but since the hotel that we liked no longer seemed to be available through our tour operators, we ended up going to Sal. When we first visited Boa Vista, there was little to be found outside of the hotel other than deserted beaches and the crashing of the Atlantic waves on the seashore. There was a very large hotel on the other side of the island and a smattering of smaller hotels dotted around, but that was it. After several visits we began to notice that other hotels were popping up along the seashore and there was a definite sense of development to cater for the holiday trade. The same can be said of Sal. The first hotel we visited had only just been built and there were the foundations of other buildings creeping up alongside but in the main, it seemed pretty deserted. Now though there are hotels everywhere and a fairly new very large one not that far away from where we stayed.

The first thing you notice as a visitor to the islands is that this is not an affluent country, far from it. Take a short trip into the town centre and you very rapidly see and sense the pervading poverty. This is a former Portuguese colony, and it comes as no surprise that it played a strategic role in the slave trade until the late nineteenth century whereupon it saw a rapid economic decline. Tourism has boosted the economy and plays a significant role in the country’s population, and this became even more evident during our latest visit. The country is only just recovering from the pandemic and several of the hotels were still mothballed as were the various businesses along the sea front. I’m not sure what the situation was or is in the country with regards to welfare, but I wouldn’t mind betting that they’d never heard of the word furlough, let alone implemented any such scheme. Quite simply no tourism means no work and no work means no wages, such as they are. In conversation with a number of the staff at the hotel, it became obvious that they were not only pleased we were there, but that they wanted us to return again. We were often asked if we would come back and one person, I spoke to pleadingly asked us to return as ‘we need the job’. Of course, it’s not just us that need to return, it’s all the tourists. Tourism supports so many aspects of the economy, not just jobs in hotels but local businesses as well. I think the fact that we keep going back there says something about the lovely people that we’ve been privileged to meet.

But then as I sat one night contently sipping a gin and tonic, debating whether I should have another before dinner, I began to think about whether all of this was ethical. The hotel we stayed in was part of a large international chain. Nearly all the hotels are part of large multinational corporations servicing their shareholders. Whilst my relaxation and enjoyment is great for me, it is on the back of the exploitative nature of the service industry. A business that probably doesn’t pay high wages, those working in the service industry in this country can probably attest to that, so goodness knows what it’s like in an impoverished place such as Cape Verde. My enjoyment therefore promotes exploitation and yet vis-a- vie enables people to have much needed work and pay. Of course, I may have this all wrong and the companies are pouring millions into the country to improve living standards for the inhabitants, and they may pay wages that are very reasonable. But somehow, because of the nature of business, and the eye on profit margins, I very much doubt it. When businesses consider business ethics, I wonder how far they cast the ethical net? As for me, it’s a bit of Catch 22, damned if you do and damned if you don’t. But then so much of life seems to be like that.

Staff Changemaker of the Year 2022: Paula Bowles

Recently I received a nomination for a Changemaker Award, even more surprising, last night I won the Staff Changemaker of the Year Award. You can see the nomination below:

As our regular readers will now, we’ve been blogging for over five years on a variety of different and diverse topics, always with criminology at their heart. However, the pandemic changed the blog beyond recognition. Whilst our bloggers and readers were still fascinated by criminology, the worries and fears around the pandemic and lockdown, made concentration challenging for all of us. For me the turning point was David Hockney’s (2020): Do Remember They Can’t Cancel the Spring

It seemed to me that we all needed something to ease the pressure and so My Favourite Things was born. It offered every blogger the opportunity to think about things (other than the pandemic), and to reflect on what mattered to them on a personal level. Each of these entries are a snapshot of the time at which they were written and were completed by a wide range of additional reflections around the Pandemic and Me. Each of these showed the need we had for human contact, for a place to discuss, vent and escape from everyday life. The blog became a focal point for many, as illustrated by our viewing figures:

I have loved reading since childhood, it plays an important part in my mental health, my equilibrium, my identity. As I’ve noted before, my guilty pleasure lies in the crime fiction of Agatha Christie. I thought if reading works such magic for me, maybe a book club would offer space, time and companionship to other people. The only rules were the book must focus on broad elements of criminology, it needed to be fiction and no one in the club had read it before.

The first book, chosen by me, was a disastrous read, confusing narrative, one-dimensional characters and a very unlikely story. But, we took our book seriously, lots of heated discussion, particularly around whether or not it was a easy to move a dead body around (thanks to @5teveh we know that’s not possible). Lots of laughter and a complete break from everything else. After that the books became much better in content and characterisation (apart from one!).

I am not sure the above makes me a worthy winner of a Changemaker Award, but I do know that none of it was possible without my fellow readers and bloggers. So a big thank you to them and of course, our readers, without whom the blog would be a much quieter affair.

“No Police in Schools”: What Happens When Teachers Act Like Police?

As an educator, I have a conscious investment in the Education system. However, I’m also one of those people some would define as a “pracademic” (practitioner-academic) who still works within the fields he teaches about (in this context creative writing and history). Though with much of my writing having a socially scientific slant, I’m always thinking about education as a site of violence and liberation … most recently Child Q and the role of teachers possibly as police in disguise (at least in terms of thinking and culture). While I see arguments for removing police officers from schools, I wonder if that would do much … other than be a symbolic gesture. I do agree police shouldn’t be in schools, but the culture of policing is everywhere. The only thing that seperates police officers from others is the added state powers.

When Britons consider the problems with UK policing, I am uncertain if this stretches beyond the uniform to how some educators in schools and universities act like cops. Even after the Murder of Sarah Everard, there are many people who I have found struggle to contemplate that the main job of The Police is to uphold the status quo and that includes protecting property (i.e the streets) even if that means steamrolling The People from the streets (i.e protesters). Moreover, Child Q (a Black child) was brutalised by London Met in 2020 further discussed in a 2022 report while a Mixed-Race child (known under alias Olivia) was similarly brutalised in May 2022 strip-searched whilst on her period. There has since been a third victim shedding light on the extremities of London Metropolitan Police’s strip-search practices.

When I was a sabbatical officer at Northampton, I sat on a number of disciplinary panels where panel members questioned students with the same manner as a police officer. Considering these students were largely Black (in my experience) and the panellists white, these encounters always had very racist overtones. Talking to white students, the offenses Black students were punished for … white students would boast about even with staff knowing. Based on the 2011 census Black people are 3% of the population (the 2021 data will be different … whenever released). However, during my 2019-20 sabbatical year, investigated deaths after police contact were disproportionate (Andrews, 2016; IOPC, 2017/18). And while 3% of the population was Black, we also make up 13% of prisoners (Andrews, 2019: xxiii).

With many Black British students at Northampton from north and south London (where if you are Black, you are also at greater risk of being stopped by police), the fact these panel members acted like police simply adds harm revisiting the strained race relations between Black civilians and white institutions (including police, education, and healthcare). This also revisits the sociohistorical significance of the relationship between ‘white masters and enslaved Black people’ with the crimes of yesterday playing out today causing harm tomorrow. The recent Living Black report simply adds to that. And as an educator who does go into schools, I know policing does happen in classrooms whether those schools have police officers on site or not. As Carla Shalaby (2017) writes these students as:

“…the caged canaries, children who are more sensitive than their peers to the toxic environment of the classroom that limits their freedom, clips their wings, and mutes their voices.”

When I tell people (let’s be honest largely white people) that I am no fan of the Police, they often respond with individual positive experiences they have had with individual police officers as a way to silence my experience. Often along the lines of my dad’s a police officer and a good just man … how could you hate him? Silencing through “whataboutery” unwilling to acknowledge that race and policing has a British history to it that goes way back to at least the 1919 Race Riots. As historian James Walvin (1973) writes

“All neutral observers agreed that the black community was on the defensive and yet its members, in trying to defend themselves were arrested and prosecuted for their attempts at self-defence, while all but a handful of the white aggressors went unchallenged” (p207).

Generally, I need a very good reason to call the Police because I know even if you call them for help, they can turn on you (especially if you’re Black). I know if I call the Police to an incident, I am not only putting myself in danger but also every Black person in a two-mile radius in danger. Britain is not America and they do not have guns as standard issue, but we must also not pretended that violence begins and ends with guns. Yet, seemingly many white people I have spoken to seem to find it more difficult (in my experience) to consider the institution of policing and how that institution is violent and harms people (even post-George Floyd). Yes, Black people are disproportionately harmed but we must not pretend we’re alone in that. Whilst you can take police officers out of schools (and university … ahem), that ideology of discipline and control can still reside in staff when given power within spheres of influence.

The book Policing the Crisis (Hall and Colleagues, 1978) recognised a change in authoritarian measures levied against Britain’s Black communities that was largely done with public consent in the 1970s. The media took the role in narrating ‘social knowledge’ of street crime and created a mythology around the “mugger” which street crime was racialised against. Thus social anxieties around young people and “urban space” and young Black people (especially males) was viewed through. I see these social anxieties still playing out today as young Black children are policed in classrooms, not necessarily by police officers but by teachers maintaining “law and order.” This is further complicated by adultification where Black children are seen as older than they are – more “adult-like”, more “sexual”, more “mature.”

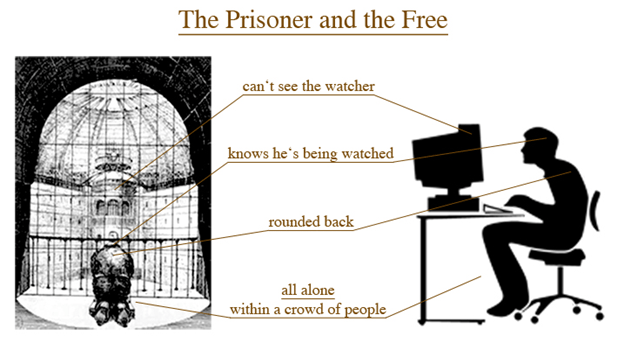

At a university level, I know this policing happens in housing and accomodation. Whilst as a sabbatical officer at Northampton between 2019-20, I spoke to Black students who had experienced racist incidents from Residential Life, and these students would not make complaints out of fear much in the same culture of Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish and Jeremy Bentham’s “panopticon.” These students knew they were being watched and policed in different ways, but they could not point at the aggressor.

As Nirmal Puwar states

“There is an undeclared white masculine body underlying the universal construction of the enlightenment ‘individual’. […] In the face of a determined effort to disavow the (male) body, critics have insisted that the ‘individual’ is embodied, and that it is the white male figure … who is actually taken as the central point of reference. […] It is against this template, one that is defined in opposition to women and non-whites — after all, these are the relational terms in which masculinity and whiteness are constituted — that women and ‘black’ people who enter these spaces are measured” (Puwar, 2004: 141).

When I was sixteen, I was one of those students that was excluded (put in internal isolation for three days for talking in class … definitely a disproportionate reaction to the misdemanour). And here, I know this experience is relatively mild in proxmity to many of my Black peers at other schools who were being punished multiple times a week (and others expelled). When many white people talk to me about school, the common denominator is that it was somewhere they felt relatively safe. Now, I get emails from Black parents of Black children and white parents of Black Mixed-Race children about racism in schools and how the schools don’t do anything. The policing of Black racialised bodies within schools is a further discussion to be had, and my community in Northamptonshire is not beyond criticism.

The frequency to which I hear Black students are punished at school and university is alarming, not surprising to see the the crossover between race and prison … as well as neurodiversity and prison where those who are seen to be “difficult” invading the space of the classroom are punished: “we have, then, a public execution and a timetable, they do not punish the same crimes nor the same type of delinquent, but they each define a certain penal style” (Foucault, 1975: 7). In this context, Foucault was talking about the man who pulled a penknife on King Louis XIV. The man was publicly drawn and quartered. He is then compared to the schedule of a prisoner in the House of Prisoners eighty years later. Two very different punishments but both ultimately damaging in different ways and products of different épistemes.

However, what I draw from this is how in today’s society, difference is punished, and there is a longevity and immediacy to the punishment. For example, the school-to-prison pipeline sees a figurative drawn-quartering of its victims that sees children through mechanisms of punishment all their lives. If they do manage to escape the prison system, that record is held over their head. Our tendency is to see medieval punishments as less humane than today’s punishment systems as if there is such thing as “progressive” violence. Yet, things like social murder (hostile environment; austerity; Cost of Living) can be compared to a slow genocide while things like the British Empire are relegated as historical relics (historical indeed?)

With the de/underfunding of the police over the last decade (Fleetwood and Lea, 2022), the greater threat sits in ideologies of control which can be picked up by anybody. Norman Fairclough (1994) argued power is “implicit within everyday social practices …. at every level in all domains of life” (p50). Philip Zimbardo’s 1971 Stanford Prison Experiment is a another example. When ordinary people were given the simultative power of prison guards, that power went to their heads. Those who volunteered to be “prisoners” were subjected to that and some were traumatised. Except in schools, they are not volunteers. We do not actually need police in schools for the simulation of policing to be carried out, as teachers and other school staff can carry this out just as academics have done in my experience at university level!

The practices of prisons “… produces subjected and practiced bodies, “docile” bodies. Discipline increases the forces of the body (in economic terms of utility) and diminishes these same forces (in political terms of obedience). In short, it dissociates power from the body; on the one hand, it turns it into an ‘aptitude’, a ‘capacity’, which it seeks to increase; on the other hand, it reverses the course of the energy, the power that might result from it, and turns it into a relation of strict subjection” (Foucault, 1975: 138)

discipline and punish: the birth of the prison

Foucault also argued that since the 1600s, practices of pushing “obedience through discipline and routine” have pervaded through other spheres “as if they tended to cover the entire social body” (Foucault, 1975: 139). The dissemination of internal / external exclusions, detentions, reprimands, housepoints, praise for 100% attendance (as if students aren’t allowed to be ill?) For students with learning differences, neurodivergent (dis)abilities, physically disabilities, as well as those with mental-ill health (and more), this is also ableism practiced through the norms of the institution.

Schools prepare students for the workforce creating drones rather than full human beings. As someone that is also autistic, I remember my teachers centralising the ideas of “fitting in” and how I did not fit in with their aesthetic of existing in the world. There sits the epistemic violence where the mainstream knowledge of socialising children with other children becomes the be all and all. The routine of conformity culture and those who do not conform are disciplined and punished in various ways, where discipline to me in school was being forced to fit in (basically ABA [autistic conversation therapy]) and thus impeded my ability to construct my own identity as someone who is not neurotypical.

Ultimately because power is not exercised exclusively through physical dominance, but cultural dominance through the stories we tell and the images that get produced. We become institutionalised by the practices we have routinely been subjected to whether that be school or the prison, thus transforming ourselves – not into the best humans we can be as humans – but as “docile bodies.” Those of us that do put in the work of unlearning what we have been conditioned into are then stigmatised. We are seen as “agitators” and “trouble” as the institution protects itself. This unlearning is not bloodless and if we are to ever have a decolonial society, we must encourage and support those who go against the grain and the norms of our institutions. Not make examples of them (Ahmed, 2018; 2021).