Home » Criminology (Page 18)

Category Archives: Criminology

“Quelle surprise” – another fine mess

The recent HMICFRS publication An inspection of vetting misconduct and misogyny in the police service makes difficult reading for those of us that have or have had any involvement in the police service in England and Wales. Of course, this is not the first such report and I dare say it will not be the last. There is enough evidence both academic and during the course of numerous inquiries to suggest that there is institutional corruption of all sorts in the police service, coupled with prevailing racist and misogynistic attitudes. Hardly a surprise then that public confidence is at an all-time low.

As with so many reports and associated inquiries, the finger of blame is pointed at the institution or individuals within it. The failings are organisational failings or departmental or individual. I cast my mind back to those inquiries into the failings of social services or the failings of NHS trusts or the failings of the Fire and Rescue service or any other public body, all the fault of the organisation itself or individuals within it. Too many inquiries and too many failings to count. More often than not the recommendations from these reports and inquiries involve rectifying processes and procedures and increasing training. Rarely if ever do these reports even dare to dip their toe into the murky waters relating to funding. Nobody on these inquiries would have the audacity to suggest that the funding decisions made in the dark corridors of government would later have a significant contribution to the failings of all of these organisations and the individuals within them. Perhaps that’s why those people are chosen to head the inquiries or maybe the funding decisions are long forgotten.

Twenty percent budget cuts in public services in 2010/11 meant that priorities were altered often with catastrophic consequences. But to be honest the problems go much further back than the austerity measures of 2010/11. Successive governments have squeezed public services in the interest of efficiency and effectiveness. The result, neither being achieved, just some tinder box ready to explode into disaster. And yet more hand wringing and finger pointing and costly inquiries.

The problem is not just that the organisations failed or that departments or individuals failed, the problem is that all the failings might have been prevented if there was money available to deliver the service properly in the first place. And to do that, there needs to be enough staff, enough training, and enough equipment. And who is responsible for ensuring that happens?

Now you may say that is all very well but what of the police officers that are racist and misogynistic or corrupt and what of institutional corruption? After all the HMICFRS report is not just about vetting procedures but about the attitudes and behaviours of staff. A good point but let me point you to the behaviour of government, not just this government but preceding governments as well. The expenses scandal, the bullying allegations, the improper behaviour in parliament, the complete disregard for the ethics or for that matter, common decency. And what of those successive budget cuts and lack of willingness to address very real issues faced by staff in the organisations.

Let me also point you to the behaviour of the general public from whom the police officers are recruited. A society where parents that attend children’s football matches and hurl abuse at the referee and linesmen, even threatening to see them in the car park after the match. Not a one off but from recent reports a weekly occurrence and worse. A society now where staff in shops are advised not to challenge shoplifters in fear of their own safety. A society where there is a complete disregard for the law by many on a daily basis, including those that consider themselves law abiding citizens. A society where individuals blame everyone else, always in need of some scapegoat somewhere. A society where individuals know individually and collectively how they want others to behave but don’t know or disregard how they should behave.

I’m not surprised by the recent reports into policing and other services, saddened but not surprised. I’m not naïve enough to think that society was really any better at some distant time in the past, in fact there were some periods where it was definitely worse and policing of any sort has always been problematic. My fear is we are heading back to the worst times in humanity and these reports far from highlighting just an organisational problem are shining a floodlight on a societal one. But it suits everyone to confine the focus to the failings of organisations and the individuals within them. Not my fault, not my responsibility it’s the others not me, quelle surprise.

The dance of the vampires

We value youth. There is greater currency in youth, far greater than wisdom, despite most people when they are looking back wishing they had more wisdom in life. Modernity brought us the era of the picture and since then we have become captivated with images. Pictures, first black and white, then replaced by moving images, and further replaced by colour became an antidote to a verbose society that now didn’t need to talk about it…it simply became a case of look and don’t talk!

The image became even more important when people turned the cameras on themselves. The selfie, originally a self-portrait of reclusive artists evolved into a statement, a visual signature for millions of people using it every day on social media. Enter youth! The engagement with social media is regarded the gift of computer scientists to the youth of today. I wonder how many people know that one of the first images sent as a jpeg was that of a Swedish Playboy playmate the ‘lady with the feathers’. This “captivating” image was the start of the virtual exchange of pictures that led to billions of downloads every day and social media storing an ever-expanding array of images.

The selfie, brought with it a series of challenges. How many times can you take a picture, even of the most beautiful person, before you become accustomed to it. Before you say, well yes that is nice, but I have seen it before. To resolve the continuous exposure the introduction of filters, backgrounds and themes seems to add a sense of variety. The selfie stick (banned from many museums the world over) became the equipment, along with the tripod, the lamp and the must have camera, with the better lens in the pursue of the better selfie. Vanity never had so many accessories!

The stick is an interesting tool. It tells the individual nature of the selfie. The voyage that youthful representation takes across social media is not easy, it is quite a solitary one. In the representation of the image, youth seem to prefer. The top “influencers” are young, who mostly like to pose and sometimes even offer some advice to their followers. Their followers, their contemporaries or even older individuals consume their images like their ‘daily (visual) bread’. This seems to be a continuous routine, where the influencer produces images, and the followers watch them and comment. What, if anything, is peculiar about that? Nothing! We live in a society build on consumption and the industry of youth is growing. So, this is a perfect marriage of supply and demand. Period!

Or is it? In the last 30 years in the UK alone the law on protecting children and their naivety from exploitation has been centre stage of several successive governments. Even when discussing civil partnerships for same sex couples, Baroness Young, argued against the proposed act, citing the protection of children. Youth became a precious age that needed protection and nurturing. The law created a layer of support for children, particularly those regarded vulnerable. and social services were drafted in to keep them safe and away from harm. In instances when the system failed, there has been public outrage only to reinforce the original notion that children and young people are to be protected in our society.

That is exactly the issue here! In the Criminology of the selfie! Governments introducing policies to generate a social insulation of moral righteousness that is predicated on individual – mostly parental – responsibility. The years of protective services and we do not seem to move passed them. In fact, their need is greater than ever. Are we creating bad parents through bad parenting or are people confronted with social forces that they cannot cope with? The reality is that youth is more exposed than ever before. The images produced, unlike the black and white photos of the past, will never fade away. Those who regret the image they posted, can delete it from their account, but the image is not gone. It shall hover over them for the eternity of the internet. There is little to console and even less to help. During the lockdown, I read the story of the social carer who left their job and opened an OnlyFans account. These are private images provided to those who are willing to pay. The reason this experience became a story, was the claim that the carer earned in one month of OnlyFans, more than their previous annual income. I saw the story being shared by many young people, tagging each other as if saying, look at this. The image that captures their youth that can become a trap to contain them in a circle of youth. Because in life, before the certainty of death there is another one, that of aging and in a society that values youth so much, can anyone be ready to age?

As for the declared care for the young, would a society that cares have been closing the doors to HE, to quality apprenticeships, a living wage and a place to live? The same society that stirs emotions about protection, wants young people to stay young so that they cannot ask for their share in their future. The social outrage about paedophiles is countered with high exposure to a particular genre in the movies and literature that promotes it. The vampire that has been fashioned as young adult literature is the proverbial story of an (considerably) older man who deflowers a young innocent girl until she becomes infatuated with him. The movies can be visually stunning because it involves the images of young beautiful people but there is hardly any mention of consent or care!

It is one of the greatest ironies to revive the vampire image in youth culture. A cultural representation of a male prototype that is manipulative, intruding into the lives of seemingly innocent young people who become his prey. There is something incredibly unsettling to explore the semiology of an immortal that is made through a blood ritual. A reverse Peter Pan who consumes the youth of his victims. The popularity of this Victorian literary character, originally conceived in the era of industrial advancement,at a time when modernity challenged tradition, resurfaces with other monsters at times of great uncertainty. The era of the picture has not made everyday life easier, and modernity did not improve quality of life to the degree it proclaimed. Instead, whilst people are becoming captivated by ephemera they are focused on the appearance and missing substance. An old experience man, dark, mysterious with white skin may be an appealing character in literature but in real life a someone who feeds on young people’s blood is hardly an exciting proposition.

The blood sacrifice demanded by a vampire is a metaphor of what our society requires for those who wish to retain youth and save their image into the ether of the cyberworld as a permanent Portrait of Dorian Gray. In this context, the vampire is not only a man in power, using his privilege to dominate, but a social representation of what a consumer society places as the highest value. It is life’s greatest irony that the devouring power of a vampire is becoming a representation of how little value we place on both youth and life! A society focused on appearance, ignoring the substance. Youth looking but not youth caring!

The Color Purple, The Musical: What in the Misogynoir?!

TW: mentions of rape, child rape, racism, and misogynoir.

Alice Walker’s novel The Color Purple is a story loved around the world. So, when I saw that it was adapted to stage and touring the UK, my interest was peaked just enough to consider a visit to my local theatre the Royal & Derngate in Northampton. A Curve and Birmingham Hippodrome co-production, it came to Northampton in the first week of October. Largely, audiences that frequent my local theatre are overwhelmingly white – thus, watching The Color Purple it was a joy to my heart to hear Black people in my community engaging with the arts, because the last time I heard so many Black people attended, was for Our Lady of Kibeho as part of the R&D’s Made in Northampton season. This dates back to 2019, a production I reviewed for The Nenequirer showing that Northampton(shire) arts has work to do.

Social media platforms like Twitter and Instagram showed me the pretty unanimous positive praise for the Leicester-Birmingham co-production, while local critics also enjoyed it – including reviews from The Chronicle & Echo and The Nenequirer as well as further reviews by The Real Chris Sparkle and Northampton Town Centre BID. However, there were elements of the show that caused me great distress, no less than the perpetuation of misogynoir and racist stereotypes against Black men. It was deeply triggering, showing how historical trauma and vicarious trauma are ever present, including when white organisations have not done the work of protecting Black mental health when producing “Black-centred media.”

At the head of this cast, Me’sha Bryan gives a knockout performance as Celie (previous played by Whoopi Goldberg in the film) accompanied by Aaliya Zhané as Nettie, with Bree Smith as Shug Avery, and brilliant musical numbers grounded in the traditions of blues music that finds its origins in the trauma of enslaved Africans in the American South. They sang when “they got the blues” … and as far as performance and the commitment from the cast, I couldn’t ask for better.

However, whilst I have praised the musical numbers above, I did not believe it fitted with the tones of The Color Purple curating a rift between what the actors were saying and doing on stage, and the intonations of the music – as well as the lighting design. And despite the directorial position deciding the rape of a child wasn’t musical material (rightly so), the choice to have it as a passing detail with no further discussion, I found particularly off-key. This is one of the moments that highlights that The Color Purple may not have been musical material and better considered as a serious drama. I did not walk away feeling that bleak, much ado with contradictory lighting choices to character moods. The characters were feeling one away and lights did something else. By the by, rather than skip over the rape to maintain “the musicalness”, it may have been more effective to have done this story as a stage drama (with musical elements, if at all). The horrors depicted at the beginning of the novel are pretty nonexistent in musical.

So, this recent adaptation was a disappointment. Not from an acting point of view but behind-the-scenes pre-production elements like direction. The start of story includes a fourteen year-old who births two children after being raped by her father. So, the amount of trauma that exists around child sexual abuse and rape appear unconsidered when they glossed over these parts of the story. Furthermore, I do question if they consulted with any survivors when doing research for this adaptation. A ‘sensitivity consultant’ would not have gone amiss either, further to considerations of intersectionality and how cultural nuances in global, but still different Black communities, will be interpreted by white people, especially in provincial Little England.

Blown away by the musical abilities of the cast, stage productions (like much art) are often labelled as “escapist” so is not afforded the same criticality as for example – policing, education, sport and so on – we are all guilty of this and we can do better. This may be art; there were no redeeming Black characters, and Black men calling Black women “ugly” (written into the script) in full face of a white audience is cultural violence. In Northampton, the large white audience laughed at this example of ableist misogynoir, and in many ways this production felt to be played up for white audiences. Lots of white people are not used to seeing Black people as full human beings, and I do feel the play draws out our humanity. And by proxy centres white comfort with a Black aesthetic reinforced by white supremacy in media.

Disability justice activist Talia Lewis has released definitions of ableism every year since 2019. In January 2022, she discussed ableism as a violent social discourse that values people’s bodies and minds according to societally constructed ideas of “normalcy, productivity, desirability, intelligence, excellence and fitness …” Lewis (2022) states that these ideas are embedded in other violent discourses such as eugenics, capitalism, misogyny and white supremacy. The adaptation of these characters is only part of this debate, where another part may want to consider how this play has informed everpresent white superemacism pervasive across Northamptonnshire. It may impact how local white audiences may view Black people when they perceive that in this cultural text – ‘this is how Black people talk and act around each other.’

“This systemic oppression leads to people and society determining people’s value based on their culture, age, language, appearance, religion, birth or living place, “health/wellness”, and/or their ability to satisfactory re/produce, “excel” and “behave.” You do not have to be disabled to experience ableism.”

Talia Lewis (2022)

In Homegrown (hooks and Mesa-Bains, 2017), bell hooks tell us “We have to constantly critique imperialist white supremacist patriarchal culture because it is so normalized by mass media and rendered unproblematic. The products of mass media offer the tools of the new pedagogy.” Theatre is no different to films, literature or television programmes. Watching the musical, it struck me how the numbers of people who haven’t done the work of unlearning their own white supremacy would be impacted by such an adaptation (yes, as we know all humans can reproduce these isms but in a global western context, however, white supremacy has put white people on the top of that racial hierarchy).

One instance of misogynoir and ableism was underpinned by the three Black women singers (their character names escape me) who were written as Sassy Black Women inherently “comedifying” Black womanhood. Brilliant singers, but were written lazily reinforcing a damaging cultural media narrative that diminishes the three-dimensional personhoods of Black women. This was offered with no alternative. The Hypersexual Jezebel (named after the “sinful” Biblical character) appears in numbers of characters while Sofia was written as the Strong Black Woman. Black men were then written as violent, comedic relief, illiterate, and other harmful stereotypes, and domestic abuser Mr Albert is redeemed to the sound of musical harmonies and joyful lighting.

At a Northampton level, the critics from local media revisited a culture of uncritically discussing art. Stories aren’t just stories but a product of the society that created them, and we are a society that finds it easier to challenge the criminal justice system than it does liberal arts institutions, in spite of both having a say in how Black people are viewed and treated. Despite “Black theatre” not being genre, we need more shows at the Derngate that centre Blackness in Britain. And whilst commissioning and hosting shows about ‘Black issues’ is not evidence of an anti-racist commitment, it would be nice to see more shows locally about Black people in the UK by Black people.

When we do get “Black stories”, they so often centre the US, most recently The Color Purple (Oct, 2022) and Two Trains Running (Sept, 2019) – denying local audiences a context for Blackness within the United Kingdom, while recentring American Blacknesses is gaslighting through art. In November, Dreamgirls centring American Blackness is coming to the Derngate. A co-production between The Curve and the Birmingham Hippodrome, this adaptation of The Color Purple was deeply problematic on many levels that local white critics may not have picked up on because of their whiteness – drawn in by a spectacle of a “Black show”, viewed through a white gaze that is unused to talking about white supremacy as a political structure.

The white audience for these misogynoir tropes specifically – largely one of laughter – reminded me of the white gaze, with white laughter as eased white supremacy. Whiteness continues to pervade through ‘acceptable racism’ where serious digs made at Black people in-text laughed at by white people may show how white people may think about Black people in designated white spaces. A Black man seriously calling a Black woman ugly and a white audience laughing at that is incredibly revealing – a comfortableness in spaces coded as white … and how white people may act when thinking and talking about Black people in private (i.e in spaces coded as culturally white and desgined to their comfort).

“I grew up in a culture of bantering and, ngl, I love a caustic riposte. And while in certain ways I resent the current policing of language, there is a distinction. I hate to break it to you, but a “joke” in which the gag is that the person is black isn’t a joke, it’s just racism disguised as humor. A joke told to a white audience where the punch line is a racist stereotype isn’t a joke, again it’s just racism; if there is only one black person present, it’s also cowardly and it’s bullying. Jokes of this nature probably aren’t funny for black people.”

Emma Dabiri (2021: 98)

Art imitating life is one thing, but when life imitates art is another. White laughter at Black people in cultural media texts goes back to the days when blackface was on the BBC (until 1978). To see this platformed by a local arts institution then profiting from it, is revealing of how whiteness is performed and profited from, when white people think they’re not being watched. Creatives have a responsibility and so do those institutions that platform them.

Myself and fellow blogger @haleysread discuss this further in our prior entries about the scandal surrounding Jimmy Carr and Netflix. On that October evening, being one of the few Black people in the audience, it was incredibly uncomfortable. To consider art uncritically is to be entertained from a vantage point of privilege (or ignorance). Attending with my friend, to see unanimous positive feedback from the public made us feel a way, no less than from many Black people. We must always be critical; being critical is not the same as criticising, and those who are critical only take the time to be so because we care.

It is not about individual actors but about the lack of critique of institutional platforming in producing “art” that goes on to cause harm. Another fellow blogger Stephanie @svr2727 talked about misogynoir and the media in her recent webinar with the Criminology Team and Black Criminology Network. Violent mistakes in arts productions show a need not for more historical consultants, but sensitivity readers and empathy viewers. One cannot teach empathy, you either have it or you do not. Extending this gaze to screen media texts as well like Bridgerton and others, it is a further reminder that social scientists are needed at the very top of media … especially those of us that research about race, racism, and other forms of violence.

These cultural texts are rehearsed, edited, and considered by multiple hands before any public audience sees them. So, why are we still having to challenge? Simple: misogynoir, ableism, and whiteness are institutionalised and normalised socially and culturally into our day-to-day practice. No less than in “liberal” arts institutions.

“Nothing but a circus, with clowns and all.” – Malcolm X

The ‘Chocolate Cost-of-Living Crisis’

Despite the turmoil and mess the country is currently in, this week’s blog post is dedicated to chocolate, and how to maintain a very much needed chocolate fix during the cost-of-living crisis and the sh** storm which British Politics currently is. Do not even get me started on the Casey Review (2022) which has been overshadowed by that sh** storm I previously mentioned. So, in an attempt to address a serious concern plaguing us all, but disproportionately those most vulnerable, I would like to share some of my findings on the ‘chocolate cost-of-living crisis’.

Before the ‘official’ cost-of-living crisis hit, chocolate was seriously upping its price tag. What used to be 99p or £1 for branded ‘share’ bag (I mean who actually has the self-control to share a share bag?!), has now risen to a huge £1.25 per bag! Now this is for Cadbury’s ‘share’ bags (buttons, wispa bites, twirl pieces to name a few), you are looking at £1.35 for Mars products (Magic stars, Minstrels, Maltesers, MnMs)! Those of us that eat Vegan, lactose-free chocolate are looking at an even higher price tag for an even smaller product. Supermarket chocolate has also gone up in price, and remains nowhere near as scrumptious as the likes of Cadbury, Mars and even Nestle (although I myself am not a Nestle loving due to their questionable ethical practices*). But given the sh** storm the Country is currently in, and the impact of the cost-of-living crisis is having, we need chocolate more than ever! But do not fear: I have some handy tips when it comes to selecting the most reasonably priced and therefore affordable chocolate to help get us through these sh***y times.

The key when looking at the cost of chocolate, and all products, is to look at the price per g/kg. This is usually in teeny tiny writing at the bottom of the price tag on the shelves. Most chocolate (and because I am a self-proclaimed chocolate snob, I am discussing branded chocolate) is coming in around the 85p+ per 100g mark. But there are some sneaky little joys which are undercutting this, and I highly recommend stocking up!

Terry’s Milk Chocolate Orange: £1, (63p/100g): a clear winner! They have various types, dark chocolate, white chocolate and popping candy, and these vary in weights but come in between 63p/100g to 69p/100g!

Cadbury Dairy Milk (360g bar): £3, (83p/100g): the key to Cadburys is the bigger the cheaper! Do not be fooled by the smaller bars and their ‘cheaper’ price. They are not cheaper: and lets be honest who wouldn’t want 360g of chocolate over 150g?!

HOWEVER

Galaxy Caramel (135g bar): 99p (73p/100g): good news for caramel lovers! The smaller caramel bar is cheaper than the 360g Galaxy smooth milk bar (97p/100g), so in this case less is actually more!

Galaxy Minstrels ‘More to Share’ Bag: £1.99 (83p/100g): best value share bag out there at the moment. Again, do not be tricked by the smaller and what may seem like cheaper bags, because they are not!

Growing up with a single-parent father who worked the ‘mum’ shift in a warehouse meant we were very stringent and careful with money: mainly because we didn’t have much. This skill of checking value for money and the price per g/kg is something engrained within me, and something I am extremely grateful for! Check those £’s per g/kg people! It may mean you can have a treat at the end of the week, which doesn’t burn through your pockets, to help off-set the sh** we are currently dealing with.

*it has recently been brought to my attention, the unethical historical practices of Cadbury’s in relation to the Slave Trade, and their racist advertisements in the early 2000’s (not sure how I missed this)! Morally, as I try to avoid Nestle products due to their unethical practices, I will also attempt the same with Cadbury’s: but I fear this will not be an easy transition.

World Mental Health Day 2022

Monday marked World Mental Health day, that one day of the year when corporations and establishments which act like corporations tell us how much mental health matters to them, how their worker’s wellbeing matters to them. Given many sectors are affected by industrial action, or balloting for industrial action, this seems like a contradiction. Could it be possible that these industries and government are causing mental ill health, while paying lip service as a PR tool? Could it be that capitalism and inequalities associated with it are both the cause of mental health conditions and the very thing that prevents recovery from it?

Capitalism, I argue, is the root of a lot of society’s problems. The climate crisis is largely caused by consumerism and our innate need for stuff. The cost of living crisis is more like a greed crisis, since the rich are getting richer and the corporations are making phenomenal profits while small business struggle to make ends meet and what used to be the middle class are relying on food banks, getting second jobs and wondering whether they can afford to put the heating on. No wonder swathes of us are suffering with anxiety, depression and other mental health conditions. Of course, I cannot argue that capitalism is to blame for all manner of mental health conditions as that is simply not the case. There are many causes of mental health conditions which simply cannot be blamed on the environment. The mental health conditions I discuss here are the depression and anxiety that so many of us suffer as a result of environmental stressors, namely capitalist embedded society.

The mental health epidemic did not start with the current ‘crises’[1] though. Yes, the COVID-19 pandemic contributes and exacerbates already existing inequalities and the UK saw an increase in adults reporting psychological distress during the first two years of the pandemic, yet fewer were being diagnosed, perhaps due to inaccessibility of GPs during this time. Even before all these things which have exacerbated mental health conditions, prevalence of common mental disorders has been increasing since the 1990s. At the same time, we have seen in the UK, neoliberal ideology and austerity politics privatise parts of the NHS and decimate funding to services which support those with needs relating to their mental health.

I am not a psychologist but I know a problem when I see or experience one. Several months ago, I was feeling a bit low and anxious so I sought help from the local NHS talking therapies service. The service was still in restrictions and I was offered a series of six DBT-based telephone appointments. After the first appointment, I realised that this was not going to help. It was suggested to have a structure in my life. I have a job, doctoral studies, dog, home educated teenager, and I go to the gym. Scheduling and structure was already an essential part of my life. Next, I was taught coping skills. ‘Get some exercise’, ‘go for a walk’. Ditto previous session – I’m gym obsessed, with a dog I walk every day, mostly in green spaces. My coping skills were not the problem either. What I realised was that I didn’t need psychological help, I needed my environment to change. I needed my workload to be reduced, my PhD to finally end, my teenage daughter not to have any teenage problems, my dog to behave, for someone to pay my mortgage off, and a DIY fairy to fix the house I don’t have time to fix. No amount of therapy could ever change these things. I realised that it wasn’t me that was the problem – it was the world around me.

I am not alone. The Mental Health Foundation have published some disturbing statistics:

- In the past year, 74% of people (in a YouGov survey of 4,619) have felt so stressed they have been overwhelmed or unable to cope.

- Of those who reported feeling stressed in the past year, 22% cited debt as a stressor.

- Housing worries are a key source of stress for younger people (32% of 18-24-year-olds cited it as a source of stress in the past year). This is less so for older people (22% for 45-54-year-olds and just 7% for over 55s).

The data show not only the magnitude of the problem, but they also indicate some of the prevalent stressors in these respondents’ lives. Over 1 in 5 people cited debt as a stressor, and this survey was undertaken long before the cost of greed crisis. It is deeply concerning, particularly considering the anticipated increase in interest rates and the cost of energy bills at the moment.

The survey also showed that young people are concerned about housing, and this will have a disproportionate impact on care leavers who may not have family to support them and working class young people who cannot afford housing.

The causes of both these issues are predominantly fat cat employers who can afford to pay sufficient and fair wages, fat cat landlords buying up property in droves to rent them out at a huge profit, not to mention the fat cat energy suppliers making billions when half the country is now in fuel poverty. All the while, our capitalism loving government plays the game, shorting the pound to raise profits for their pals while the rest of us struggle to pay our mortgages after the Bank of England raised interest rates. No wonder we’re so stressed!

For work-related stress, anxiety and depression, the Labour Force Survey finds levels at the highest in this century, with 822,000 suffering from such mental health conditions. The Health and Safety Executive show that education and human, health and social work are the industries with the highest prevalence of stress, anxiety and depression. It is yet another symptom of neoliberalism which applies corporate values to education and public services, where students are the cash cow, and workers are exploited; and health and social work being under funded for years. Is it any wonder then that both nurses and lecturers are balloting for industrial action right now?

Despite all this, when World Mental Health Day arrives, it becomes the perfect PR exercise to pay lip service to staff wellbeing. The rail industry are in a period of industrial action, yet I have seen posts on rail companies’ social media promoting World Mental Health Day. Does the promotion of mental health initiatives include fair pay and conditions for staff? I think not.

Something needs to give, but what?

As a union member and representative, I argue for the need for employers to pay staff appropriately for the work they do, and to treat them fairly. This would at least address work and finance related stressors. Sanah Ahsan argues for a universal basic income, for safe and affordable housing and for radical change in the structural inequalities in the UK. Perhaps we could start with addressing structural inequalities. Gender, race and class all impact on mental health, with women more likely to be diagnosed with depression, Black women at an increased risk of common mental health disorders and the poor all more likely to suffer mental health conditions yet less likely to receive adequate and culturally appropriate support. In my research with women seeking asylum, there is a high prevalence of PTSD, yet therapy is difficult to access, in part due to language difficulties but also due to cultural differences. Structural inequalities then not only contribute to harm to marginalised people’s mental health, but also form a barrier to support.

I do not have a realistic solution, but I have the feeling society needs a radical social change. We need an end to structural inequalities, and we need to ensure those most impacted by inequalities get adequate and appropriate support. When I look to see who is in charge, and who could be in charge if the tides were to turn, and I don’t see this happening anytime soon.

[1] I’m hesitant to call them crises. As Canning (2017:9) explains in relation to the refugee ‘crisis’, a crisis is unforesessable and unavoidable. The climate crisis has been foreseen for decades, and the cost of living crisis is avoidable if you compare other European countries such as France where the impact has been mitigated by the government. The mental health crisis has also been growing for a long time and the extent to which we say today could be both foreseen and avoided.

The Origins of Criminology

The knife was raised for the first time, and it went down plunging into naked flesh; a spring of blood flowed cascading and covering all in red. The motion was repeated several times. Abel fell to his death and according to scriptures this was the first crime. Cain who wielded the knife roamed the earth until his demise. The fratricide that was committed was the first recorded murder and the very first crime. A colleague tried to be smart and pointed that the first crime is Eve’s violation in the garden with the apple, but I did point out that according to Helena Kennedy QC, she was framed! In the least Eve’s was a case of entrapment which is criminological but leaves the first crime vacant. So, murder it is! A crime of violence that separates aggressor and victim.

The response to this crime is retribution. In the scriptures a condemnation to insanity. In later years this crime formed the basis of the Mosaic Law inclusive of the 10 commandments and death as the indicative punishment. In the Ancien Régime the punishment became a spectacle on deterrence whilst the crowds denounced the evildoer as they were wheeled into the square! In modern times this criminality incorporated rehabilitation to offer the opportunity for the criminal to repent and make amends.

‘The first man who having enclosed a piece of ground bethought himself of saying “This is mine”’! This is an alternative interpretation of the first crime, according to Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1762/1993: 192). In The Social Contract he identifies the first crime very differently from the scriptures. In this case the crime is not directed at a person but the wider community. The usurping of land or good in any manner that violates the rights of others is crime because it places individualism ahead of the common good. As in this crime there is no violence against the person, the way in which we respond to it is different. Imperialism as a historical mechanism accepts the infringement of property, rights, and human rights as a necessity in human interactions. The law here is primarily protected for the one who claims the land rather than those who have been left homeless. In this case, crime is associated with all those mechanisms that protect privilege and property. Soon after titles of land emerged and thereafter titles of people owning other people follow. The land becomes an empire, and the empire allows a man and his regime to set the laws to protect him and his interests. Traditionally empires change from territories of land to centres of government and control of people. The land of the English, the land of the Finnish, the land of the Zulu. In this instance the King become a figure and custom law subverts natural law to accommodate authority and power.

These two “original” crimes represent the diversity in which criminology can be seen; one end is the interpersonal psychological rendition of criminality based on the brutality of violence whilst on the other end is an exploration of wider structural issues and the institutional violence they incorporate. The spectrum of variety criminology offers is a curse and a blessing in one. From one end, it makes the discipline difficult to specify, but it also allows colleagues to explore so many different issues. Regardless of the type of crime category for any person attracted to the discipline there is a criminology for all.

Between these two polar apart approaches, it is interesting to note their interaction. In that it can be seen the interaction of the social and historical priorities of crime given at any given time. This historical positivism of identifying milestones of progression is an important source of understanding the evolution of social progression and movements. Let’s face it, crime is a social construct and as such regardless of the perspective is indicative of the way society prioritises perceptions of deviance.

Arguably the crimes described previously denote different schools of thought and of course the many different perspectives of criminology. A perfectly contorted discipline that not only adapts following the evolution of crime but also theorises criminality in our society. When you are asked to describe criminology, numerous associations come to mind, “the study of crime and criminality” the “discipline of criminal behaviours” “the social construction of crime” “the historical and philosophical understanding of crime in society across time” “the representation of criminals, victims, and agents in society”. These are just a few ways to explain criminology. In this entry we explore the origins of two perspectives; theology and sociology; image that the discipline is influenced by many other perspectives; so consider their “origin” story. How different the first crime can be from say a psychological or a biological perspective. The origins of criminology is an ongoing tale of fascinating specialisms.

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques, (1762/1993), The Social Contract and Discourses, tr. from the French by G.D.H. Cole, (London: Everyman’s Library)

‘Now is the winter of our discontent’

As I write this blog, we await the detail of what on earth government are going to do to prevent millions of our nations’ populations plummeting headlong into poverty. It is our nations in the plural because as it stands, we are a union of nations under the banner Great Britain; except that it doesn’t feel that great, does it?

As autumn begins and we move into winter we are seeing momentum gaining for mass strikes across various sectors somewhat reminiscent of the ‘winter of discontent’ in 1979. A few of us are old enough to remember the seventies with electricity blackouts and constant strikes and soaring inflation. Enter Margaret Thatcher with a landslide election victory in 1979. People had had enough of strikes, believing the rhetoric that the unions had brought the downfall of the nation. Few could have foreseen the misery and social discord the Thatcher government and subsequent governments were about to sow. Those governments sought to ensure that the unions would never be strong again, to ensure that working class people couldn’t rise up against their business masters and demand better working conditions and better pay. And so, in some bizarre ironic twist, we have a new prime minister who styles herself on Thatcher just as we enter a period of huge inflationary pressures on families many of whom are already on the breadline. It is no surprise that workers are voting to go on strike across a significant number of sectors, the wages just don’t pay the bills. Perhaps most surprising is the strike by barristers, those we wouldn’t consider working class. Jock Young was right, the middle classes are staring into the abyss. Not only that but their fears are now rapidly being realised.

I listened to a young Conservative member on the radio the other day extolling the virtues of Liz Truss and agreeing with the view that tax cuts were the way forward. Trickle down economics will make us all better off. It seems though that no matter what government is in power, I have yet to see very much trickle down to the poorer sectors of society or for that matter, anyone. The blame for the current economic state and the forthcoming recession it seems rests fairly on the shoulders of Vladimir Putin. Now I have no doubt that the invasion of Ukraine has unbalanced the world economic order but let’s be honest here, social care, the NHS, housing, and the criminal justice system, to name but a few, were all failing and in crisis long before any Russian set foot in the Ukraine.

That young Conservative also spoke about liberal values, the need for government to step back and to interfere in peoples lives as little as possible. Well previous governments have certainly done that. They’ve created or at least allowed for the creation of the mess we are now in by supporting, through act or omission, unscrupulous businesses to take advantage of people through scurrilous working practices and inadequate wages whilst lining the pockets of the wealthy. Except of course government have been quick to threaten action when people attempt to stand up for their rights through strike action. Maybe being a libertarian allows you to pick and choose which values you favour at any given time, a bit of this and a bit of that. It’s a bit like this country’s adherence to ideals around human rights.

I wondered as I started writing this whether we were heading back to a winter of discontent. I fear that in reality that this is not a seasonal thing, it is a constant. Our nations have been bedevilled with inadequate government that have lacked the wherewithal to see what has been developing before their very eyes. Either that or they were too busy feathering their own nests in the cesspit they call politics. Either way government has failed us, and I don’t think the new incumbent, judging on her past record, is likely to do anything different. I suppose there is a light at the end of the tunnel, we have pork markets somewhere or other.

Criminology First Week Activity (2021)

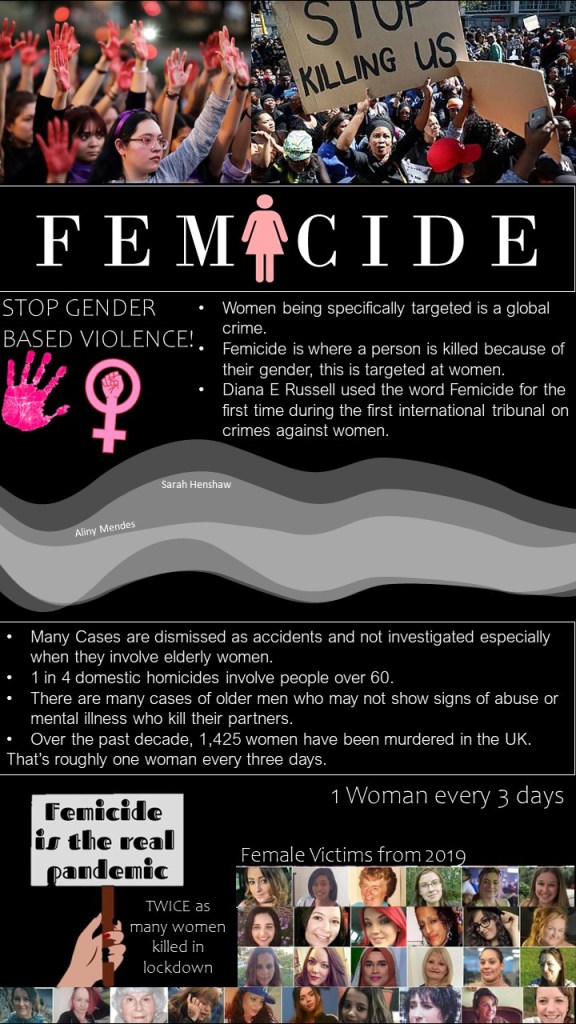

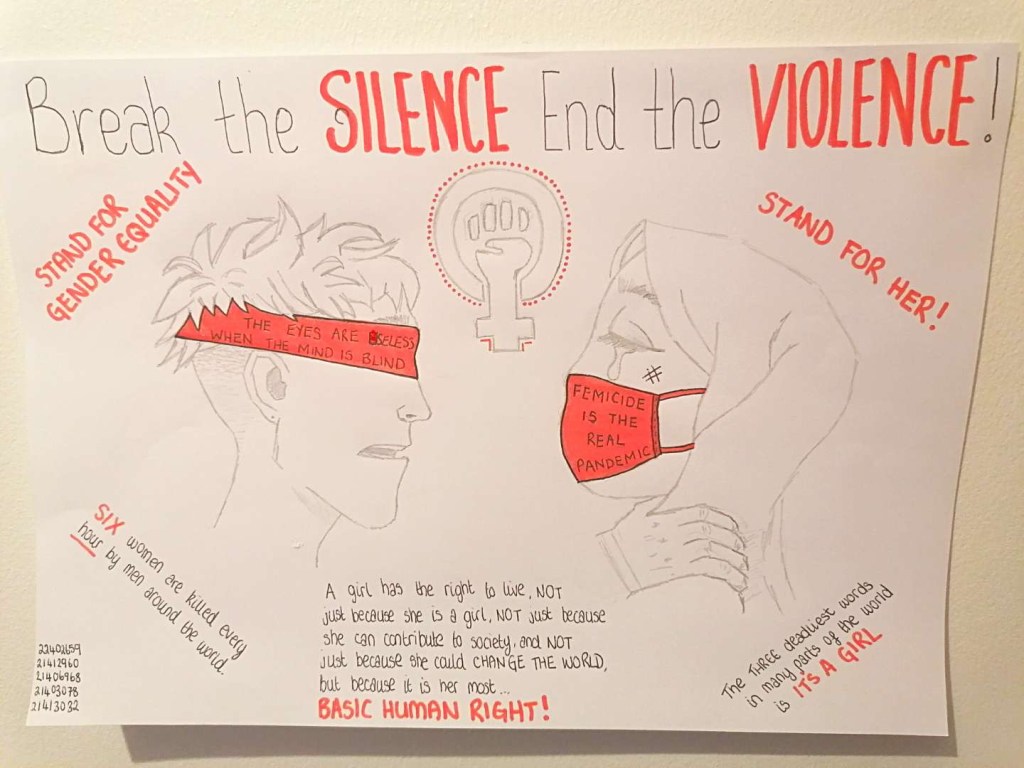

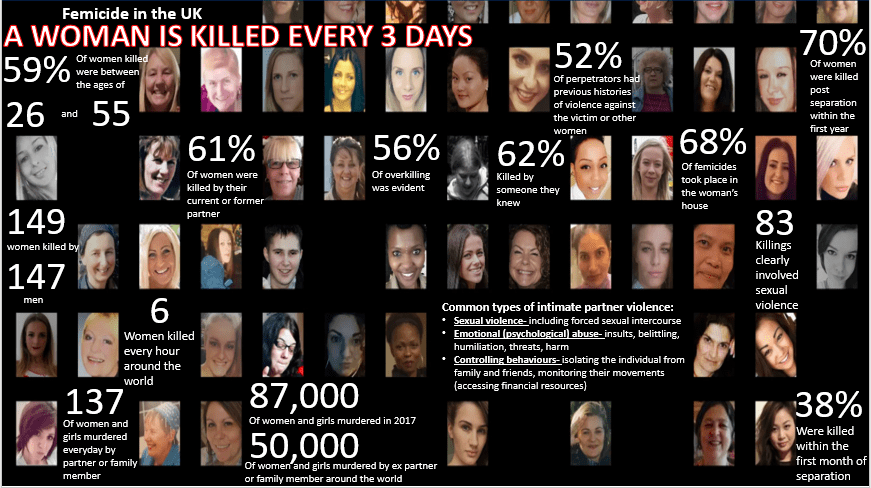

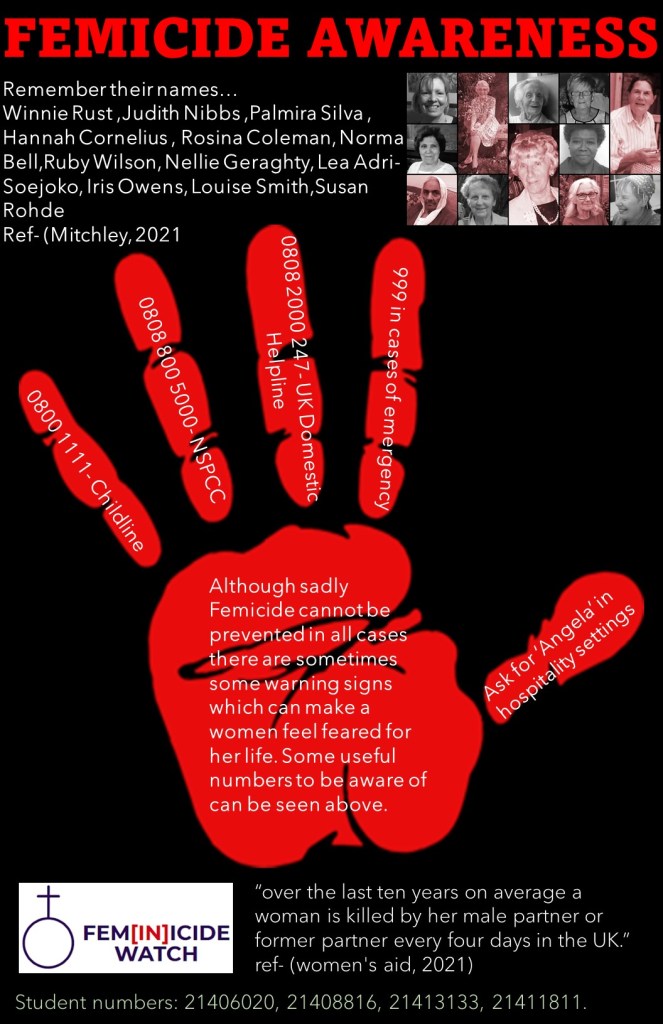

Before embarking on a new academic year, it is always worth reflecting on previous years. In 2020, the first year we ran this activity, it was a response to the challenges raised by the Covid-19 pandemic and was designed to serve two different aims. The first of these, was of course, academic, we wanted students to engage with a activity designed to explore real social problems through visual criminology, inspiring the criminological imagination for the year ahead. Second, we were operating in an environment that nobody was prepared for: online classes, limited physical contact, mask wearing, hand sanitising, socially distanced. All of these made it very difficult for staff and students to meet and to build professional relationships. The team needed to find a way for people to work together safely, within the constraints of the Covid legislation of the time and begin to build meaningful relationships with each other.

The start of the 2021/2022 academic year had its own pandemic challenges with many people still shielding, others awaiting covid vaccinations and the sheer uncertainty of going out and meeting people under threat of a deadly disease. After taking on board student feedback, we decided to run a similar activity during the first week of the new term. As before, students were placed into small groups, advised to take the default approach of online meetings (unless all members were happy to meet physically), provided with a very short prompt and limited guidance as to how best to tackle the project. The prompts were as follows:

Year 1: Femicide

Year 2: Mandatory covid vaccinations

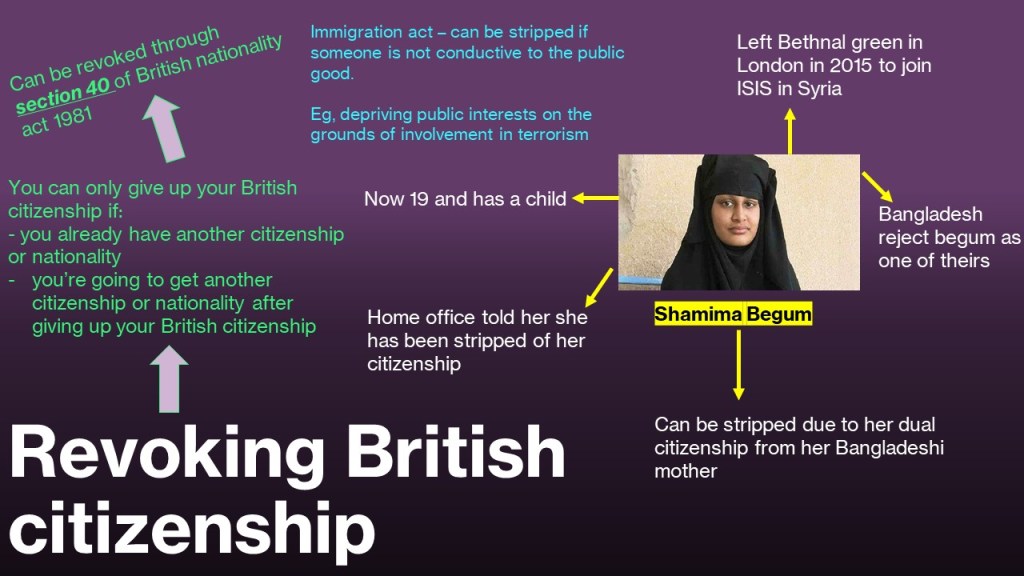

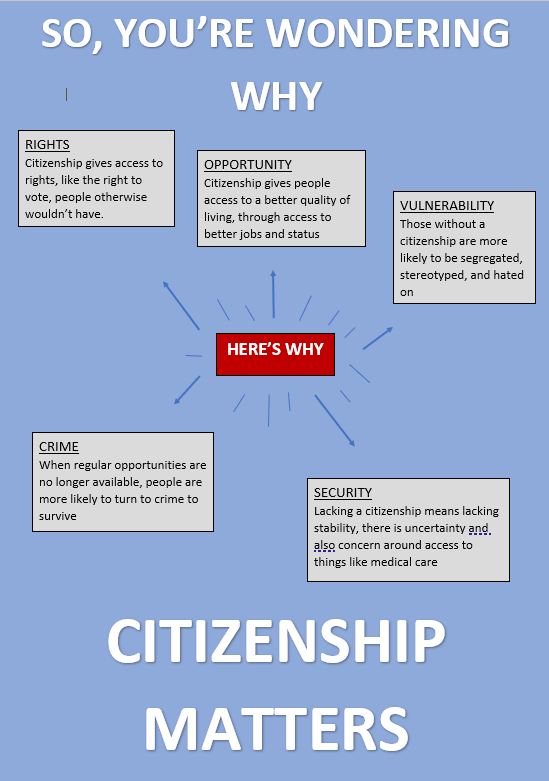

Year 3: Revoking British citizenship

Many of the students had never physically met, yet managed to come together in the midst of a pandemic, negotiate a strategy, carry out the work and produce well designed and thoughtful, criminological posters.

As can be seen from the collage below, everyone involved embraced the challenge and created some remarkable posters. Some of these have been shared previously across social media but this is the first time they have all appeared together in one place.

I am sure everyone will agree our students demonstrated knowledge, understanding, resilience and stamina. We will be running a similar activity for the first week of the academic year 2022-2022, with different prompts to provoke thought and encourage dialogue and team work. We’ll also take on board student and staff feedback from the previous two activities. Plato once wrote that ‘our need will be the real creator’, put more colloquially, necessity is the mother of all invention, and that is certainly true of our first week activity.

Who knows what exciting ideas and posters will be demonstrated this time, but one thing is for sure Criminology students have the opportunity to flex their activism, prepare to campaign for social justice, in the process becoming real #Changemakers.

The Good Doctor has me thinking…

Recently I have begun watching ABC’s The Good Doctor, which is a medical drama based in the fictional, yet prestigious, San Jose St Bonaventure Hospital and follows the professional and personal journeys of a number of characters. The show is based on a South Korean tv medical drama called Good Doctor and is produced by Daniel Dae Kim and developed by David Shore (creator of House). The main character is Dr Shaun Murphy who has Autism. He is a surgical resident in the early seasons and the show focuses on how Dr Murphy navigates his professional and personal life, as well as how the hospital and other doctors, surgeons, nurses and patients navigate Dr Murphy’s style of communication and respond to him. As a medical drama, in my humble opinion, it is highly entertaining with the usual mix of interesting medical cases and personal drama required. The characters are also relatable in a number of different areas. As a springboard for a platform to talk about equality, equity and fairness, it is accessible and thought-provoking.

A key focus of the programme is the difficulty Dr Murphy has with communication. Well, I say difficulty in communicating, but in actuality I would say he communicates differently to what is recognised as an ‘accepted’ or ‘normal’ form of communication. Dr Murphy struggles to express emotions and becomes overwhelmed when things change and are not within his controlled environment. A number of his colleagues adapt their responses and ways of interacting with him in order to support and include him, whereas others do not and argue that despite his medical brilliance, and first-rate surgical skills, he should not be treated differently to the other surgical residents, as this is deemed unfair.

Whilst watching, the claims of treating all surgical residents equally, and ensuring the hospital higher-ups are being fair; notions of John Rawls’ writing scream out at me. Students who have studied Crime and Justice should be familiar with Rawls’ veil of ignorance, liberty principles and difference principle, in particular with its reference to ‘justice’. But the difference principle weighs heavily when looking at how Dr Murphy functions within the hospital institution with its rules, procedures and power dynamics which clearly benefit and align with some people more so than others. Under the veil of ignorance, maybe an empathetic doctor or surgeon is not required, but a competent and successful one is? Maybe being empathetic is a personal circumstance rather than an objective trait? For Rawls, it is important that the opportunity to prosper is equal for all: and this might mean the way this opportunity is presented is different for different individuals. Rawls asks us to consider a parallel universe and what could be (a popular stance to take within the philosophical realm): why can’t people with autism be given the chance to save lives and perform surgeries just because they cannot communicate in a way deemed ‘the norm’ when dealing with patients.

It is possible that I am over-thinking this. And when I ask my partner about it, they raise questions about why Dr Murphy should be given different opportunities to the other residents and the harm Dr Murphy’s communication barriers could and do cause within the series. But I feel they are missing the point: it is not about different opportunities, its about different methods to ensure they all have the same opportunity to succeed as surgeons. It is not about treating everyone the same, which might on the surface appear to be fair, it is about recognising that equal treatment involves taking account for the differences. Why should Dr Murphy be measured against norms and values from an institution which is historically white, non-disabled, male, and cis-gendered? This might appear to be a lot of thought for a fictional medical drama, but to reiterate it’s an excellent programme with plenty to think about…

Bibliography:

Rawls, J. (1971) A Theory of Justice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ryan, A. (1993) Justice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Food Banks: The Deserving vs Undeserving

A term that has been grating on me recently is ‘hard work’. I have had a recent bout of watching lots of television. From my observations it appears that more commentators within the media have grasped the idea that the continued need for Food Banks in the United Kingdom is awful. Yet commentators still continue with the same old deserving/undeserving tripe which has existed for centuries (which CRI2002 students are well-aware of). That being, that we should be concerned about food banks… ‘because now even hard-working people are using them!’, aka those within formal (preferably full-time) employment.

What is it that is not being said by such a statement? That being unable to survive off benefits is perfectly fine for people who are unemployed as they do not deserve to eat? If that is the case perhaps a reconsideration of the life experiences of many unemployed people is needed.

To provide some examples, a person might claim unemployment benefits because they are feeling mentally unwell or harmful to themselves but a variety of concerns have prevented them from seeking additional support and claiming sickness benefits, in this situation working hard on survival might be prioritised over formal employment. Another person might sacrifice their work life to work hard to unofficially care for relatives who have slipped through cracks and are unknown to social services, whilst not reaching out for support due to fear/a lack of trust social services – they have good reasons to be concerned. Some people might have dropped out of formal employment due to experiencing a traumatic life event(/s) which means that they now need to work hard on their own well-being. Or, shock-horror, people may be claiming unemployment benefits because they are working hard post-pandemic to find a job which pays enough for them to survive.

Let’s not forget that many of those who access Food Banks are on sickness benefits because they cannot work due to experiencing a physical and/or mental health disability. The underserving/deserving divide appears to be further blurred these days as those who claim sickness benefits are frequently accused of being benefits cheats and therefore undeserving of benefits and Food Bank usage. Even so, the acknowledgement of disability and Food Bank usage within the media is rare.

Is it really ok to perceive that the quality of a person’s life and deserved access to necessities should depend on their formal employment status?

There is twisted logic in the recent conservative government discourse about hard work. There is the claim that if we all work hard we will reap the rewards, yet in the same breath ‘deserving hard workers’ are living from payslip to payslip due to the cost of living crisis, poor quality pay and employment. Hence the need to use Food Banks.

The conservatives hard working mantra that all people can easily gain employment is certainly a prejudiced assumption. With oppressive, profit seeking, exploitative and poor quality employment there is little room allowed for humans to deal with their personal, family life pains and struggles which makes job retention very difficult. Perhaps the media commentators need a re-phrase: It is awful that any person needs to use a Food Bank!